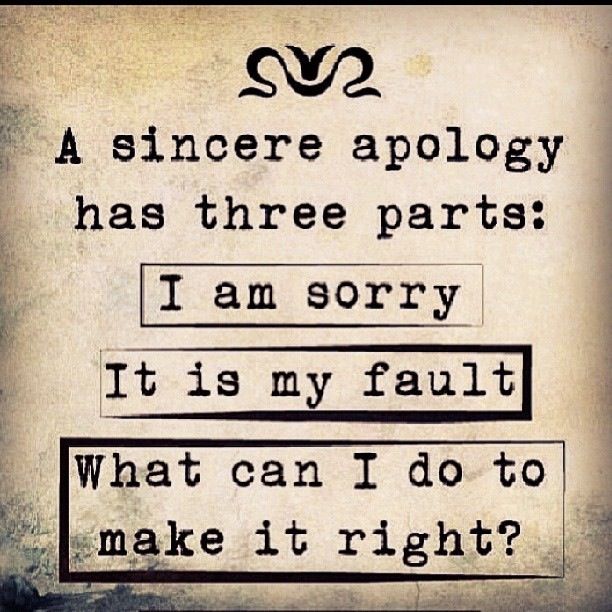

Signs of a genuine apology

What a Real Apology Looks Like

To be human is to hurt people sometimes. Yet it’s not always easy to offer a genuine apology when we’ve injured or offended someone.

We need robust inner resources and an open heart to keep from descending into denial — or slipping into a shame-freeze — when we realize that we’ve violated someone’s sensibilities. It takes courage to downsize our ego and accept our human limitations with humility and grace.

Sadly, the shame we carry often prevents us from having a friendly relationship with our shortcomings. We think we need to be perfect to be accepted and loved. When our self-image clashes with how we really are, we may scramble to defend ourselves. We blame others or make excuses rather than say with dignified humility, “I’m sorry, I was wrong.”

There’s nothing shameful to admit when we’ve made a mistake. As John Bradshaw reminds us, making a mistake is different than being a mistake. Not acknowledging shortcomings is a sign of weakness, not strength.

Repairing Conflict

For example, let’s say we get stuck at work and come home late. And we neglected to call, even though we’ve promised many times that we’d do so. Our partner is upset and asks angrily, “Where were you? Why didn’t you call?” We reply, “I’m sorry you’re upset, but you’re late too sometimes.” Our defensive comeback indicates that we’re not hearing our partner’s feelings. We attack rather than listen.

Or we might say, “I’m sorry. I wanted to call you but my battery died.” When people are hurting, even a good reason can sound like a lame excuse. They need to be met in their emotional place rather than be responded to from a rational place; they want their feelings heard.

Defensiveness escalates conflicts. When we say with a pompous tone, “Yes, I did that, but you do it to,” we’re really saying, “I have the right to hurt you because you hurt me.” Such an attitude doesn’t create a climate for healing. Avoiding accountability, we perpetuate a cycle of distance, hurt, and mistrust.

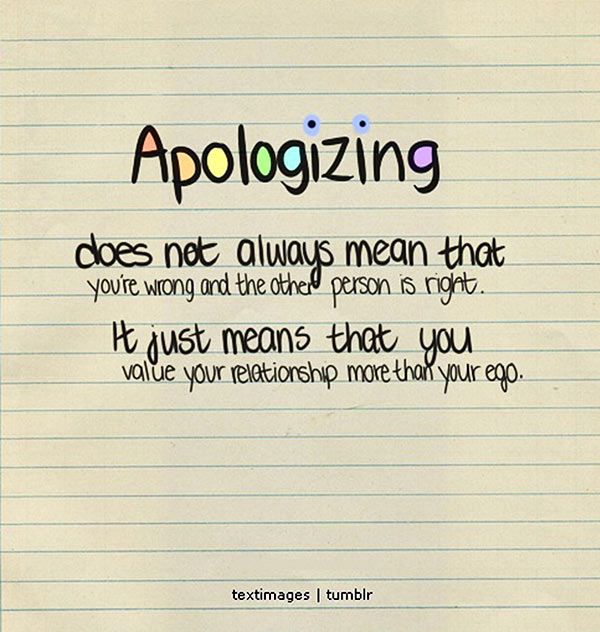

An Iffy Apology

An apology containing the words “if” or “but” is not a real apology. Saying “I’m sorry if I hurt you” signals that we’re not accepting that we did caused the hurt. If someone tells us they feel hurt, it’s best to let that in rather than offer an explanation that we hope will quickly settle the matter.

Conflicts tend to de-escalate when the injured person’s feelings are heard and respected. Maybe later we can explain what happened — when emotions have calmed. But communication works better when we slow down, take a breath, and hear the other person’s feelings.

“I’m sorry you feel that way” often contains the unspoken thought: “But you shouldn’t feel that way” or “what’s wrong with you?” We’re not allowing ourselves to be affected by the hurt we’ve caused. We’re not taking responsibility for our behavior.

We can make the case that it’s not our fault, right? But such a comeback can trigger an endless loop of counter-attacks: “Why didn’t you charge the phone properly. You’re so neglectful!” A genuine apology means we feel sorry for our behavior and for how our behavior caused hurt.

You’re so neglectful!” A genuine apology means we feel sorry for our behavior and for how our behavior caused hurt.

A Sincere Apology

Contrast the above “iffy” apology with a more sincere one, where our sorry flows from the sorrow we feel about our actions — and for the hurt we caused by not acting in a sensitive, attuned, caring way.

A more engaging response might look something like this: We look into our partner’s eyes and say with a sincere tone: “I really hear that I hurt you and I feel sad about that. We might add, “Is there anything more you want me to hear?” Or we might offer, “I blew it by not keeping my phone charged. I’ll do my best to pay more attention to that.”

Our partner might be more inclined to soften if he or she hears such a heartfelt apology. And if our partner is not receptive, at least we can know we did our best to offer a sincere apology.

The Strength to Have Humility

We all miss the boat sometimes. We don’t need to beat ourselves up for hurting someone or acting unwisely. As our self-worth grows, we can take responsibility for our actions without being burdened by the toxic shame created by self-blame.

We don’t need to beat ourselves up for hurting someone or acting unwisely. As our self-worth grows, we can take responsibility for our actions without being burdened by the toxic shame created by self-blame.

Healing happens as we find the courage to offer a genuine apology, while learning through experience to be more mindful and responsive so that we’re less likely to repeat it.

A sincere apology requires strength and humility. It requires that we rest comfortably (or perhaps a little awkwardly) in a place of vulnerability. Most important, it requires that we recognize and heal the deep-seated shame that can trigger angry, reactive responses. It’s too painful or threatening to our self-worth to notice shame inside us, may we tap into the “fight” part of the “fight, flight, freeze” response. We resort to angry protests to protect and defend ourselves rather than listen openly to another’s feelings.

Apologies cannot be forced. The demand, “You owe me an apology” is not a good setup to garner a genuine apology. And be aware that people may feel hurt based more on their history than anything you’ve done wrong. There may be times when you really didn’t do anything wrong.

And be aware that people may feel hurt based more on their history than anything you’ve done wrong. There may be times when you really didn’t do anything wrong.

Still, listening to a person’s feelings in a respectful and sensitive manner is a good starting place for repairing ruptures of trust and sorting things out. If someone is upset with you, take a deep breath, stay connected to your body (rather than dissociate), listen to the person’s feelings, and notice how you feel as you listen. Taking responsibility for even a small part of the matter — and offering a genuine apology — may go a long way toward repairing trust.

What a Real Apology Looks Like

To be human is to hurt people sometimes. Yet it’s not always easy to offer a genuine apology when we’ve injured or offended someone.

We need robust inner resources and an open heart to keep from descending into denial — or slipping into a shame-freeze — when we realize that we’ve violated someone’s sensibilities. It takes courage to downsize our ego and accept our human limitations with humility and grace.

It takes courage to downsize our ego and accept our human limitations with humility and grace.

Sadly, the shame we carry often prevents us from having a friendly relationship with our shortcomings. We think we need to be perfect to be accepted and loved. When our self-image clashes with how we really are, we may scramble to defend ourselves. We blame others or make excuses rather than say with dignified humility, “I’m sorry, I was wrong.”

There’s nothing shameful to admit when we’ve made a mistake. As John Bradshaw reminds us, making a mistake is different than being a mistake. Not acknowledging shortcomings is a sign of weakness, not strength.

Repairing Conflict

For example, let’s say we get stuck at work and come home late. And we neglected to call, even though we’ve promised many times that we’d do so. Our partner is upset and asks angrily, “Where were you? Why didn’t you call?” We reply, “I’m sorry you’re upset, but you’re late too sometimes. ” Our defensive comeback indicates that we’re not hearing our partner’s feelings. We attack rather than listen.

” Our defensive comeback indicates that we’re not hearing our partner’s feelings. We attack rather than listen.

Or we might say, “I’m sorry. I wanted to call you but my battery died.” When people are hurting, even a good reason can sound like a lame excuse. They need to be met in their emotional place rather than be responded to from a rational place; they want their feelings heard.

Defensiveness escalates conflicts. When we say with a pompous tone, “Yes, I did that, but you do it to,” we’re really saying, “I have the right to hurt you because you hurt me.” Such an attitude doesn’t create a climate for healing. Avoiding accountability, we perpetuate a cycle of distance, hurt, and mistrust.

An Iffy Apology

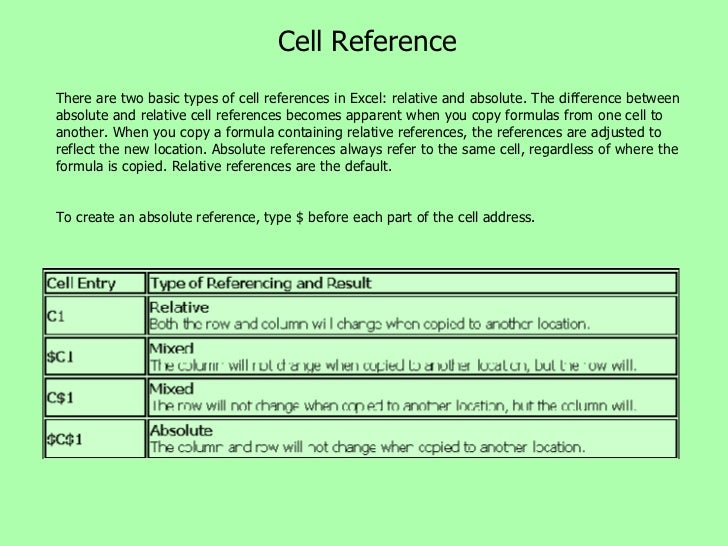

An apology containing the words “if” or “but” is not a real apology. Saying “I’m sorry if I hurt you” signals that we’re not accepting that we did caused the hurt. If someone tells us they feel hurt, it’s best to let that in rather than offer an explanation that we hope will quickly settle the matter.

Conflicts tend to de-escalate when the injured person’s feelings are heard and respected. Maybe later we can explain what happened — when emotions have calmed. But communication works better when we slow down, take a breath, and hear the other person’s feelings.

“I’m sorry you feel that way” often contains the unspoken thought: “But you shouldn’t feel that way” or “what’s wrong with you?” We’re not allowing ourselves to be affected by the hurt we’ve caused. We’re not taking responsibility for our behavior.

We can make the case that it’s not our fault, right? But such a comeback can trigger an endless loop of counter-attacks: “Why didn’t you charge the phone properly. You’re so neglectful!” A genuine apology means we feel sorry for our behavior and for how our behavior caused hurt.

A Sincere Apology

Contrast the above “iffy” apology with a more sincere one, where our sorry flows from the sorrow we feel about our actions — and for the hurt we caused by not acting in a sensitive, attuned, caring way.

A more engaging response might look something like this: We look into our partner’s eyes and say with a sincere tone: “I really hear that I hurt you and I feel sad about that. We might add, “Is there anything more you want me to hear?” Or we might offer, “I blew it by not keeping my phone charged. I’ll do my best to pay more attention to that.”

Our partner might be more inclined to soften if he or she hears such a heartfelt apology. And if our partner is not receptive, at least we can know we did our best to offer a sincere apology.

The Strength to Have Humility

We all miss the boat sometimes. We don’t need to beat ourselves up for hurting someone or acting unwisely. As our self-worth grows, we can take responsibility for our actions without being burdened by the toxic shame created by self-blame.

Healing happens as we find the courage to offer a genuine apology, while learning through experience to be more mindful and responsive so that we’re less likely to repeat it.

A sincere apology requires strength and humility. It requires that we rest comfortably (or perhaps a little awkwardly) in a place of vulnerability. Most important, it requires that we recognize and heal the deep-seated shame that can trigger angry, reactive responses. It’s too painful or threatening to our self-worth to notice shame inside us, may we tap into the “fight” part of the “fight, flight, freeze” response. We resort to angry protests to protect and defend ourselves rather than listen openly to another’s feelings.

Apologies cannot be forced. The demand, “You owe me an apology” is not a good setup to garner a genuine apology. And be aware that people may feel hurt based more on their history than anything you’ve done wrong. There may be times when you really didn’t do anything wrong.

Still, listening to a person’s feelings in a respectful and sensitive manner is a good starting place for repairing ruptures of trust and sorting things out. If someone is upset with you, take a deep breath, stay connected to your body (rather than dissociate), listen to the person’s feelings, and notice how you feel as you listen. Taking responsibility for even a small part of the matter — and offering a genuine apology — may go a long way toward repairing trust.

Taking responsibility for even a small part of the matter — and offering a genuine apology — may go a long way toward repairing trust.

What distinguishes sincere apologies from fake

Man and woman

As a psychotherapist, I often hear apologies or regrets from clients. Sometimes they say them simply because they want to change the subject, when they are not really remorseful. Or they say this to calm their spouse or spouse if they came together, or when they feel a personal defeat. All these apologies are useless, because they are insincere, they do not help to improve relations.

Only true repentance helps to get closer. They show that you really care about your partner, their thoughts and feelings. Unsuccessful apologies, on the contrary, spoil the relationship more. Let's give some examples.

1. “Sorry, sorry, sorry.” These passive-aggressive "apologies" are said simply to change the subject and silence the partner. They show that you do not take his experiences seriously.

2. "I'm sorry it happened, but...". "But" is a clause that changes everything. If you can't apologize without a "but," then you're not sorry. This is just an attempt to justify.

3. "I'm sorry for ... but not for...". The first is usually some small thing, and the second is a major offense. So you try to avoid responsibility and passive-aggressively transfer the blame to your partner.

4. "I'm sorry, but you yourself...". This is how you put all the blame on your partner. Such an apology is not sincere.

5. "I'm sorry it happened." An overly generalized apology without any specifics shows that you are not really ready to take responsibility for your actions.

6. "Sorry" (with laughter). Laughter sounds like a mockery of the interlocutor and his feelings about what happened, as if you are trying to belittle him.

7. "Sorry" (with tears). Excessively emotional regrets with tears are also not sincere. You put on a show and turn attention to yourself, forgetting about those who suffered from your actions.

Excessively emotional regrets with tears are also not sincere. You put on a show and turn attention to yourself, forgetting about those who suffered from your actions.

8. "I'm sorry I hurt you." In the right situation, this expresses sympathy. But often such a phrase seems to hint to the partner that he is too vulnerable and sensitive.

9. "Sorry for the interruption." You are afraid of conflict or want to hear "Yes, you don't bother me." This shows your deep insecurity and disrespect for the interlocutor.

10. "Sorry, but I don't agree." Again, usually in this way you are trying to soften the subsequent aggressive attack towards the partner.

11. "Well, I'm sorry." To do this in an exaggerated and sarcastic manner is a mockery of the partner's feelings.

12. "I'm sorry" (for no reason). It devalues the moments when repentance is really needed. Usually this is done out of shame or trying to get rid of unpleasant emotions.

Usually this is done out of shame or trying to get rid of unpleasant emotions.

13. "I plead guilty when you do this." This is an attempt to turn an apology into a contest in which there must be a "winner" who is ready to admit guilt only after the partner does.

14. "I will only apologize once." This is an attempt to control your partner, you demand to forgive you here and now, regardless of his feelings.

15. Refusing to ask for forgiveness. If you refuse to do this when necessary, you show pride and an inability to repent.

16. Too frequent confessions. Yes, sometimes one "I'm sorry!" not enough to show remorse, but too frequent are no longer taken seriously.

17. Trying to make amends with gifts. Some people are not ready to discuss misdeeds, preferring instead to give expensive presents. At the same time, they do not accept responsibility for what happened and are not ready to change.

18. Attempts to distract from feelings of guilt. Sometimes we are so tormented by this feeling that we start doing useless things to distract ourselves. The problem is that it doesn't help repair the relationship.

True repentance can change the dynamics of a relationship, heal wounds, strengthen intimacy, love, and mutual support.

1. Apologize for specific things. List why you are doing this, without reservations. Sometimes it's better to write it down on paper.

2. Use correct intonation. You need to find the right balance, not falling into hysterics with sobs, but not remaining indifferent. Show that you sympathize with your partner and regret the pain they have caused.

3. After you've done this, really change your behavior. Repentance is not just a momentary impulse, it leads to long-term changes that will require time and patience.

4. Don't just throw around excuses. It is worth doing only when you are guilty, then your words will be taken seriously.

It is worth doing only when you are guilty, then your words will be taken seriously.

5. Make up after an apology. It is not enough to ask for forgiveness, you need to reconcile on terms that suit both.

If both partners abide by these rules and avoid false apologies, the relationship is good. It is always joyful to see repentance, the desire to fix everything and live in love and harmony.

About the author

Christine Hammond is a psychologist. Her website.

Source: pro.psychcentral.com

Text: Nikolai Protsenko Photo credit: Getty Images

New on the site

8 travel movies that change lives0003

How rest and exercise affect your career: proven ways to work more efficiently and productively

“I choose men who are disappointed in girls to show them true love”

“See a guy every one or two months: career is more important for him than relationships »

Sex without obligation: a big discussion with psychologists - study all the pros and cons

"Once in a lifetime": how to choose a spouse and guarantee happiness - psychologist's opinion

A normal man of the 21st century: what is he like? 7 key ideas

Test: Who do you think about more - about yourself or others?

90,000 psychologist Blog: How to learn to forgive and apologize- Elena Savinova

- Psychologist

Author photo, Nikuliahin/Getty

"Healing" Vehi ". - sung in a somewhat sad lyrical song. Indeed, sometimes it is unbearably difficult to apologize. And even harder to forgive.

- sung in a somewhat sad lyrical song. Indeed, sometimes it is unbearably difficult to apologize. And even harder to forgive.

- Why do we want to take revenge?

- How to learn not to believe in tears?

- Psychologist's blog: is it necessary to get into the soul and phone of a loved one?

- Psychologist's blog: why do we tell lies?

Against whom are we friends?

For someone to ask for forgiveness means to humiliate themselves. Say, it's useless, because you can't fix anything anyway. For other, more frivolous people, it's child's play.

Some people think that they can do whatever they want and then apologize - and it's like nothing happened. Such people are sincerely surprised when they continue to be offended. After all, they uttered that cherished word.

Then they themselves are offended that they were not given something with the same ease with which they acted ugly. And accusations and resentments accumulate like a snowball. Although former friends no longer really remember who started it first, who owes what to whom.

And accusations and resentments accumulate like a snowball. Although former friends no longer really remember who started it first, who owes what to whom.

I agree, the word "sorry" probably takes second place after "love" in terms of meaninglessness. Or vice versa - according to the fullness of all possible, often very contradictory, meanings. Saying "I love you" is partly about claiming, demanding, not working on the relationship anymore. And behind the words of forgiveness sometimes lies compulsion, indifference, neglect, hidden hostility.

Some resort to a false apology to lull the enemy's vigilance and deliver a sensitive blow.

Petrenko is not a pig? I apologize...

Nevertheless, the very act of forgiveness is very important in human communication. By apologizing, you say that you recognize the fallacy of your act, you regret it. And also express the hope for understanding and the possibility of continuing the relationship. Since we are all different, our ideas of "good" and "bad" are different, so the ability to apologize will allow you to avoid unnecessary insults and enemies.

Since we are all different, our ideas of "good" and "bad" are different, so the ability to apologize will allow you to avoid unnecessary insults and enemies.

It is important to remember that you are asking for, not demanding, forgiveness. Therefore, you will have to calmly accept the unwillingness to forgive you for your oversight or unpleasant behavior.

Try to apologize immediately after the incident. Find out the reasons for the strange act of your friends here and now. Do not hide or accumulate resentment in yourself, drawing in your imagination their most incredible motives.

Let go

To be able to admit one's unworthy behavior with sincere repentance is a sign of a strong and adult personality. And to be able to really sincerely "forget" someone's deceit, dishonesty, indifference towards you - the highest aerobatics.

Image copyright Unsplash

There is an opinion that being offended is more profitable than being guilty. So many people like to feel offended. Firstly, in this way they find confirmation of their own children's complexes. As if no one loves them, everyone only takes advantage of their weaknesses. As if they are not capable of anything, so you can "wipe your feet" about them.

So many people like to feel offended. Firstly, in this way they find confirmation of their own children's complexes. As if no one loves them, everyone only takes advantage of their weaknesses. As if they are not capable of anything, so you can "wipe your feet" about them.

Secondly, those who once casually or even deliberately offended them can be manipulated to their heart's content. For years, a wife remembers some kind of guilt for her husband in order to get behavior that is beneficial for herself.

Or the more successful, smart and beautiful one always feels a little guilty towards her "ordinary" friend because she is more "lucky". Therefore, he arranges a job for her, lends money, brings gifts. But once you refuse - and the benefactor turns into a sworn enemy.

Offended by equals

Skip the podcast and continue

podcast

0003

Releases

End Podcast

So, if you've done your best, but they don't want to forgive you, stop trying.