Shared delusional disorder

Shared Psychotic Disorder - StatPearls

Continuing Education Activity

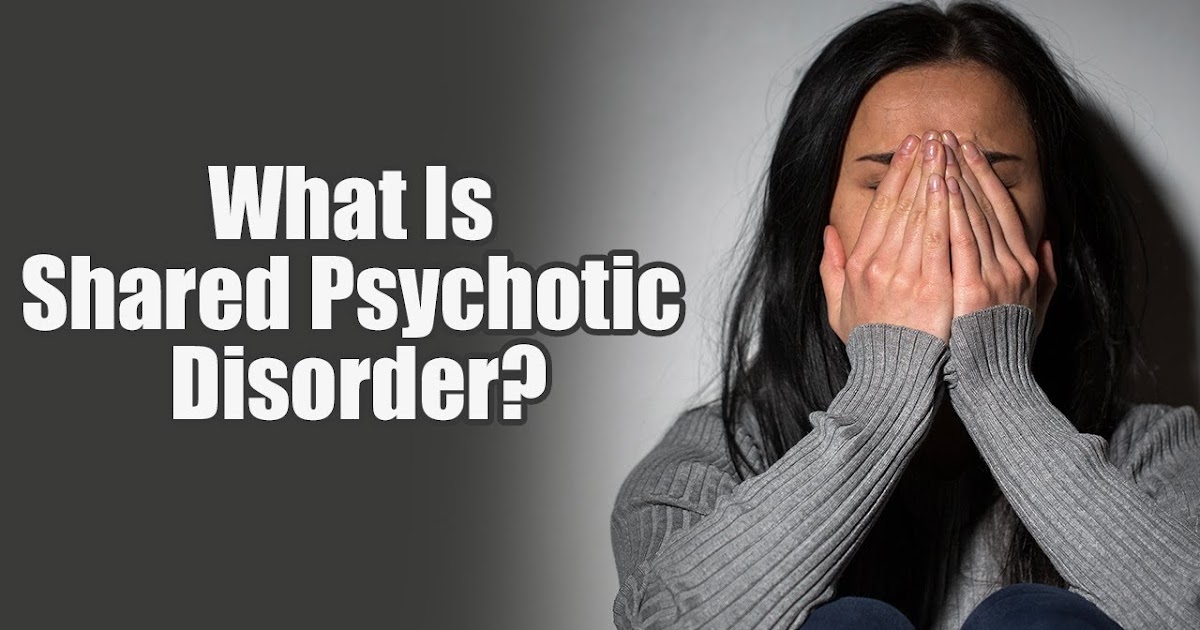

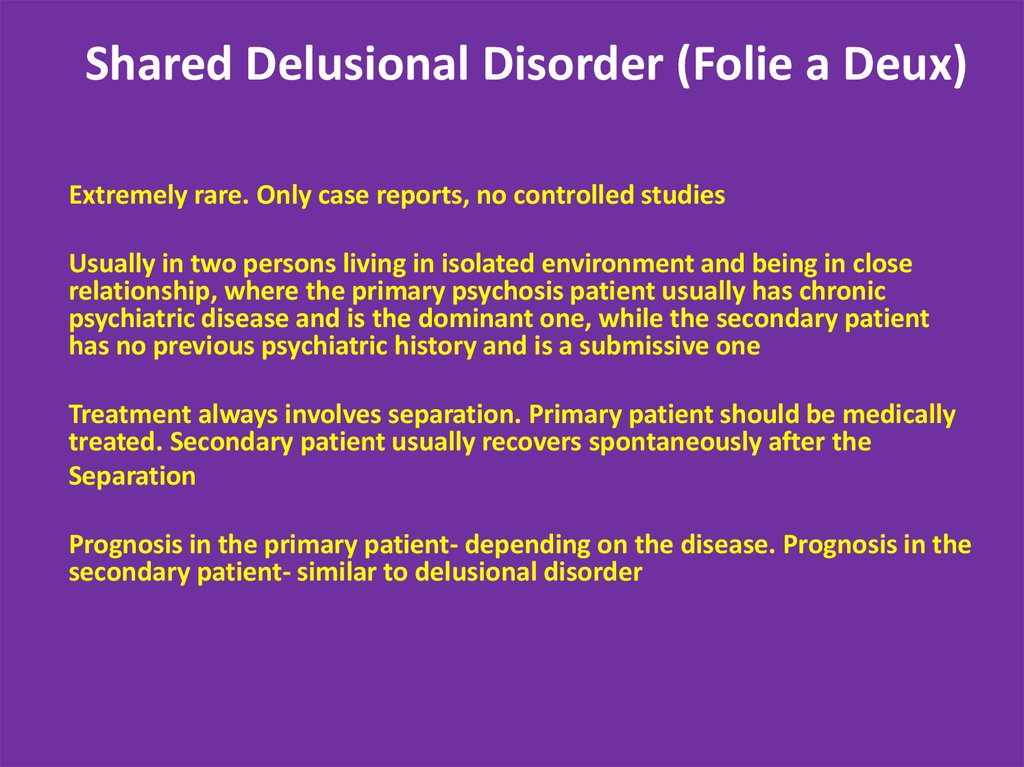

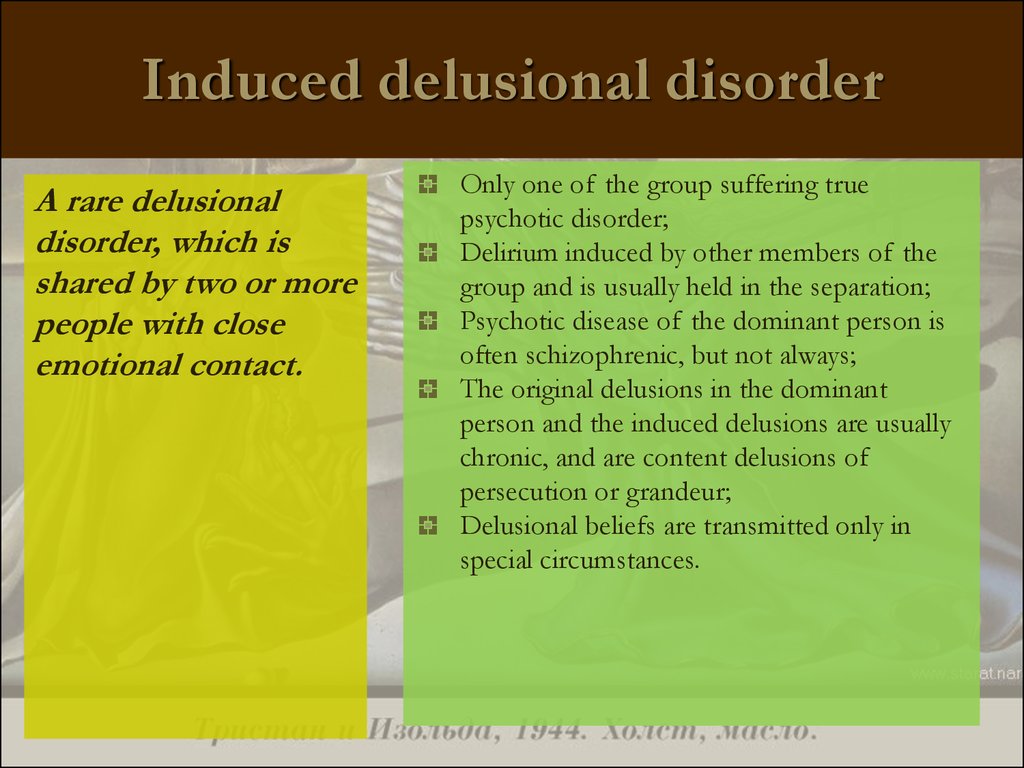

Shared psychotic disorder (folie à deux) is a rare disorder characterized by sharing a specific delusion among two or more people in a close relationship. The inducer (primary) who has a psychotic disorder with delusions influences another individual or more (induced, secondary) based on a delusional belief. It is commonly seen among two individuals, but in rare cases, can include larger groups. This activity outlines the presentation and management of shared psychotic disorder and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving the care of patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Review risk factors for shared psychotic disorder.

-

Describe the pathophysiology of shared psychotic disorder.

Outline the treatment and management options available for shared psychotic disorder.

Describe the importance of collaboration and communication amongst an interprofessional team to improve outcomes for those affected by shared psychotic disorder.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

Shared psychotic disorder (folie à deux) is a rare disorder characterized by sharing a delusion among two or more people in a close relationship. The inducer (primary) who has a psychotic disorder with delusions influences another nonpsychotic individual or more (induced, secondary) based on a delusional belief. It is commonly seen among two individuals, but in rare cases, can include larger groups. For example, it can occur in a family and is called folie à famille.[1][2]

Jules Baillarger was the first to report this condition in 1860. During the 19th century, psychiatrists in Europe suggested different names. In France, it has been called "folie communiquee"(communicated psychosis) by Baillarger. In German psychiatry, it was named "Induziertes Irresein" by Lehman and Sharfetter. In 1877 Lasegue and Falret coined the term “folie à deux.” The French word “folie à deux" means madness shared by two. In the early 1940s, Gralnick, in his review of 103 cases of folie à deux, described four types of this disorder. He defined it as a psychiatric entity characterized by the transfer of delusions from one person to one or several others who have a close association with the primarily affected person. The four types are as follows:

In the early 1940s, Gralnick, in his review of 103 cases of folie à deux, described four types of this disorder. He defined it as a psychiatric entity characterized by the transfer of delusions from one person to one or several others who have a close association with the primarily affected person. The four types are as follows:

Folie imposee (imposed psychosis) - Described by Lasegue and Falret in 1877. The delusions are transferred from an individual with psychosis to an individual without psychosis in an intimate relationship. The delusions in the induced individual soon disappear once the two are separated.

Folie simultanee (simultaneous psychosis) - Described by Regis in 1880. Both partners share the psychosis simultaneously. They both have risk factors through long social interactions that predispose them to develop this condition. There are reports of sharing genetic risk factors among siblings.

Folie communiquée (communicated psychosis) - Described by Marandon de Montyel in 1881.

This type is similar to folie imposee; however, the delusion in the secondary partner occurs after a long period of resistance. Also, the secondary partner will maintain the delusion even after separation from their partner.

This type is similar to folie imposee; however, the delusion in the secondary partner occurs after a long period of resistance. Also, the secondary partner will maintain the delusion even after separation from their partner.Folie induite (induced psychosis) - Described by Lehmann in 1885. In this type, new delusions are assumed by an individual with psychosis who is being influenced by another individual with psychosis.

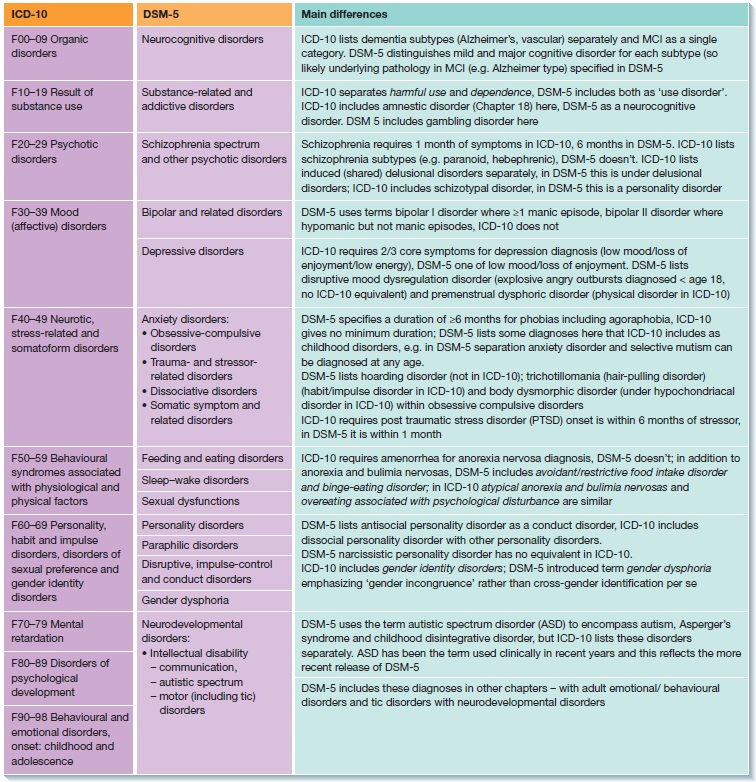

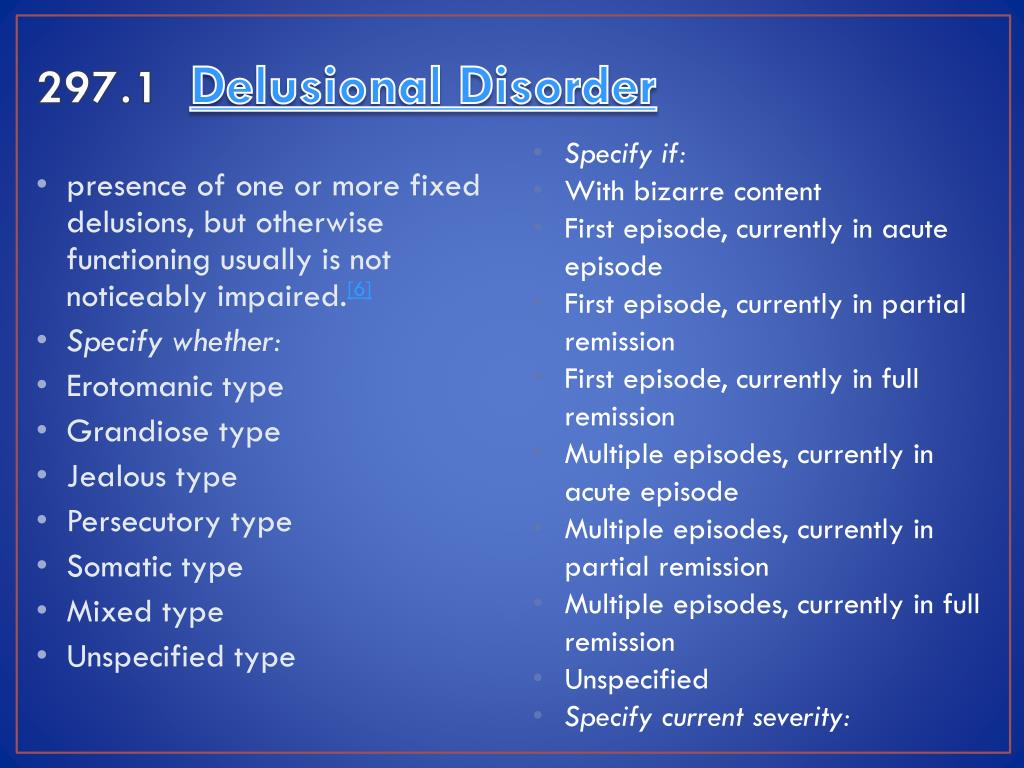

This disorder was first listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III) as shared paranoid disorder. In the next edition (DSM-IV), the term changed to shared psychotic disorder. In the latest edition, DSM-5, it was removed as a separate disease entity. It now is included in the section on other specified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. ICD-10 lists it as induced delusional disorder.[2]

Etiology

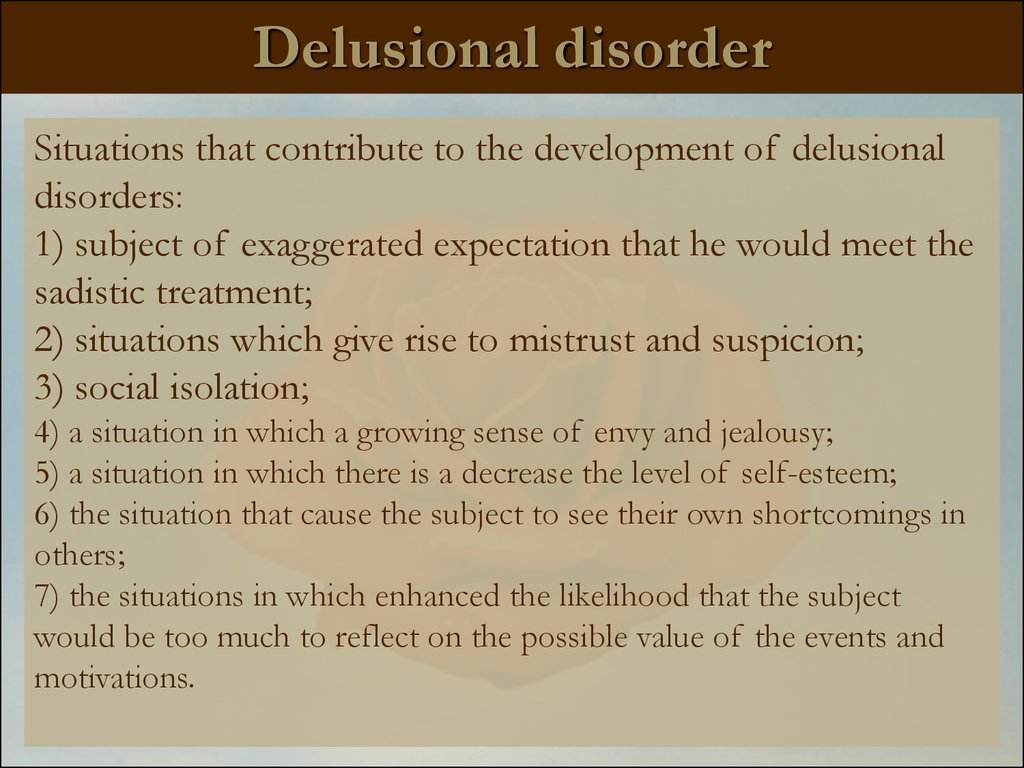

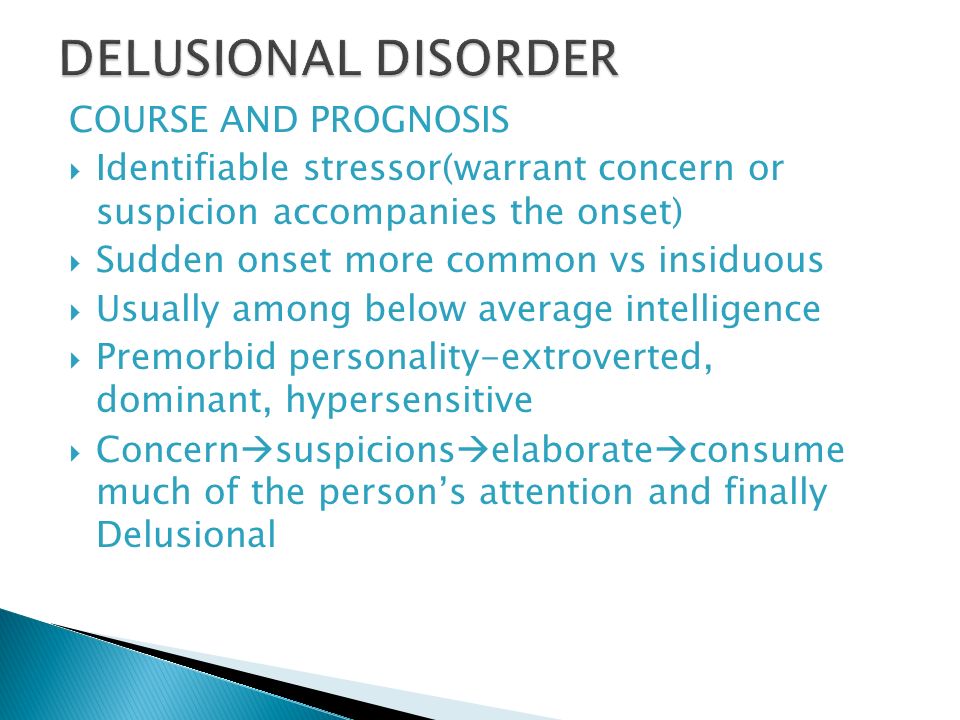

The exact cause of shared psychotic disorder is still unknown. However, certain risk factors associated with it include the following:

However, certain risk factors associated with it include the following:

Length of the relationship: Numerous studies highlight the role of long relationship duration as an essential factor for developing this condition. It is crucial to understand that the attachment with the inducer plays a key role in adopting the delusion.[3]

Nature of the relationship: The majority of cases reported are among family members. The commonest relationship is between married or common-law couples, and the second most common is between sisters.[3]

Social isolation: Most reported cases indicate poor interaction with society. A confused individual can undergo influence under frightening conditions in the absence of social comparison. The information received by the secondary individual is in harmony with what the primary individual felt. The conviction of certain ideas will eventually prevail as the only solution to maintain a mutual relationship.[4]

Personality disorder: Individuals usually show features of a personality disorder.

The usual description for them is neurotic, introverted, and emotionally immature. Some case reports noticed features of premorbid personality disorders especially dependent (passive), schizoid, and schizotypal.[5][6]

The usual description for them is neurotic, introverted, and emotionally immature. Some case reports noticed features of premorbid personality disorders especially dependent (passive), schizoid, and schizotypal.[5][6]Untreated mental disorder in the primary: An untreated individual with chronic mental conditions can be a social risk factor of influence to the other partner or family. The commonest diagnosis in the primary is a delusional disorder followed by schizophrenia and affective disorder.[3]

Cognitive impairment: It has been noted that the secondaries lack good judgment and intelligence.[4]

Comorbidity of the secondary: An individual diagnosed with a mental disorder, including schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, depression, dementia, or intellectual disability, carries a risk of being influenced by another mentally ill person.[4]

Life events: Stressful life events that affect the relationship can influence behavior in the individual to accept certain delusions or lessen their ability to resist their feelings or emotions.

For example, a wife who has been suffering from delusions for several years starts accusing her husband, who has erectile dysfunction, of being in a relationship with a mistress or that the mistress is “stimulating him with sildenafil and narcotics.” He will eventually accept this belief because of his unstable, passive personality condition, as well as the serious situation from which he suffers.[5]

For example, a wife who has been suffering from delusions for several years starts accusing her husband, who has erectile dysfunction, of being in a relationship with a mistress or that the mistress is “stimulating him with sildenafil and narcotics.” He will eventually accept this belief because of his unstable, passive personality condition, as well as the serious situation from which he suffers.[5]Communication difficulties: Having difficulty sharing ideas can be a reason for preferring isolation. It is suggested that improving communication among dyad relationships through multiple-conjoint psychotherapy may help both partners understand the different points of view that will collapse in the presence of rigid, mindless thinking.[7]

Age: Previous studies reported age differences, the older of the two in the relationship being an inducer and the younger being the induced. However, recent studies do not support this finding.[2]

Gender: The disorder is more common among females, both as a primary or secondary.

[2]

[2]

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of shared psychotic disorder are difficult to estimate. However, some studies report that it is responsible for 1.7 to 2.6% of psychiatric hospital admissions.[8] This figure may, however, be underestimated as it is underdiagnosed and often missed in clinical practice. Psychiatrists may treat the primary while not being aware that the delusions exist in others.[9] Some authors even argue that the disorder is not rare.[3]

Pathophysiology

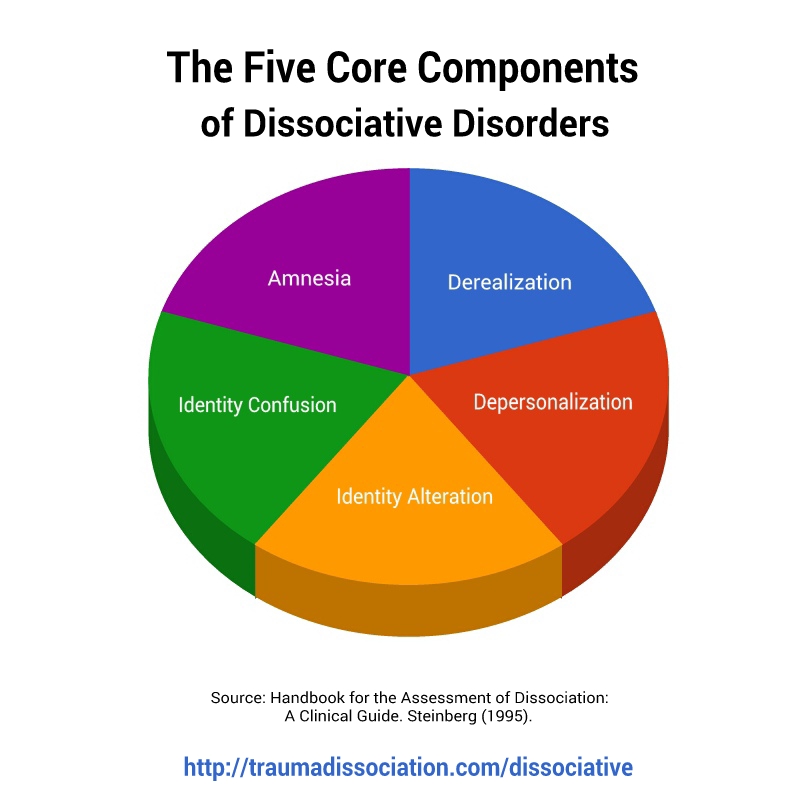

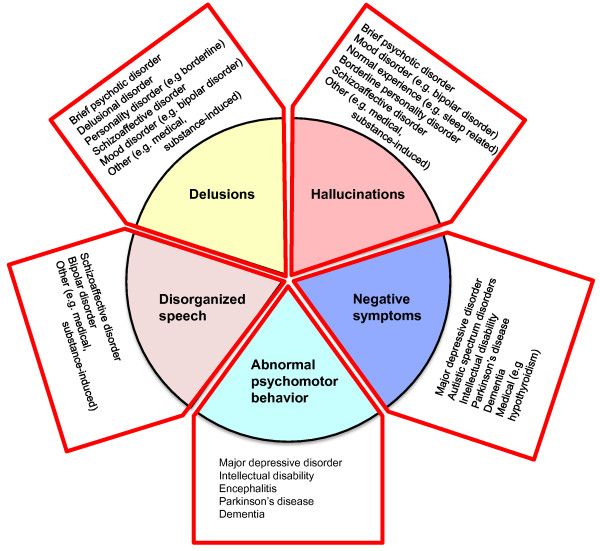

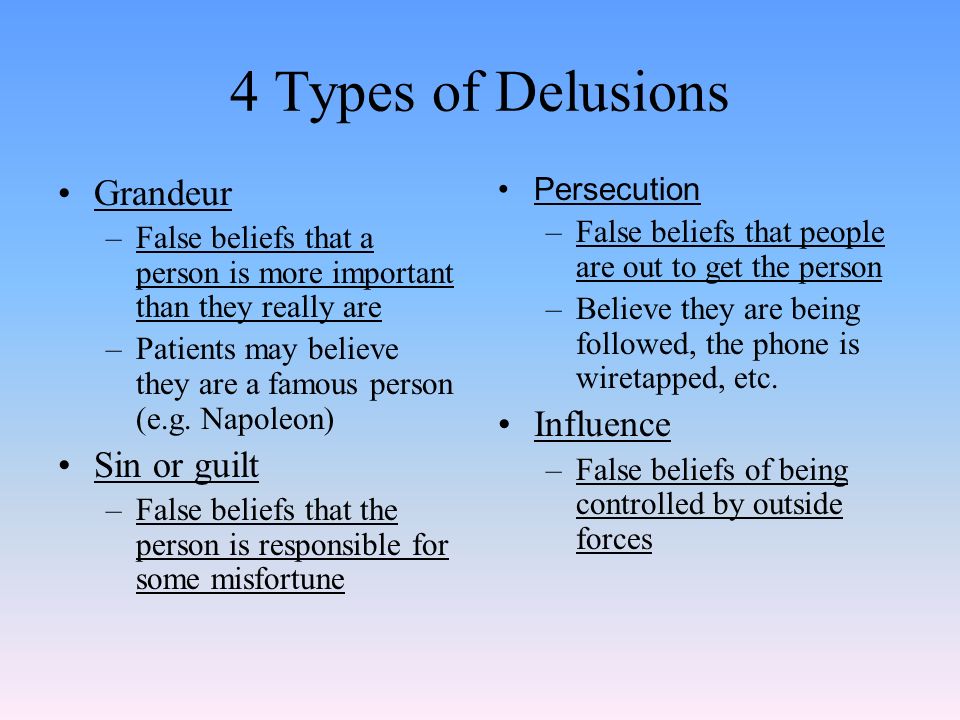

Shared psychotic disorder usually is chronic, and both the primary and secondary individuals share the original delusion(s). The shared delusion(s) occur under unique circumstances and can be of any type. The most common type of delusion is persecutory, followed by grandeur. There are racial variations. For example, in Japanese communities, persecutory delusions are the commonest followed by religious delusions.[4][10] There may be other psychiatric features such as social withdrawal, hallucinations, or suicidal thoughts. [11] Functionality is generally preserved compared with other disorders. There may be significant impairment in a particular aspect of life, especially when the delusions are not confronted.

[11] Functionality is generally preserved compared with other disorders. There may be significant impairment in a particular aspect of life, especially when the delusions are not confronted.

The concept of the dominant-submissive relationship is derived from the psychodynamic theory. The role of the primary is rigid and possessing (dominant) while the submissive is less intelligent, passive, less resilient to suggestions, isolated, and/or physically handicapped. [6] Some authors have emphasized the existence of a role reversal between partners due to the complexity of the disorder.[7]

History and Physical

Presentation depends on the type of shared delusion. One partner usually faces a problem in society that involves the intervention of a psychiatrist. Often, this problem is supported or under the influence of the other partner. Both exhibit unrealistic, fixed, false beliefs which are unshakable. They might be paranoid, fearful, and suspicious of a neighbor or someone in their community. One might seek mental assessment after risky behavior, unreal claims, or recent assault. The secondary partner can be mistakenly referred and usually discovers that other people within their social sphere share the same belief as the primary. There can be under-treated or undiagnosed cases within the community that last for several years before being discovered. Sometimes partners who shared particular delusions can be admitted to the hospital together because of risky behavior or assault on themselves or others.

One might seek mental assessment after risky behavior, unreal claims, or recent assault. The secondary partner can be mistakenly referred and usually discovers that other people within their social sphere share the same belief as the primary. There can be under-treated or undiagnosed cases within the community that last for several years before being discovered. Sometimes partners who shared particular delusions can be admitted to the hospital together because of risky behavior or assault on themselves or others.

General description: The couples usually are groomed and well dressed.

Behavior: Defensive attitude or angry behavior can occur towards an interviewer who challenges the patient's delusion(s).

Speech: The patient's speech usually is coherent and relevant.

Mood and Affect: Mood is usually congruent with the delusion; a paranoid patient may be irritable, while a grandiose patient may be euphoric.

Thought: The form of thought is usually goal-oriented. The delusions are shared either entirely or partially; often are not bizarre in content; are systematically structured; overvalue social, cultural, or religious beliefs beyond the community norms; and can include homicidal or suicidal ideation.

The delusions are shared either entirely or partially; often are not bizarre in content; are systematically structured; overvalue social, cultural, or religious beliefs beyond the community norms; and can include homicidal or suicidal ideation.

Perceptions: They are less likely to express abnormal perceptions unless there are predisposing factors. Sometimes the secondary is the only person who experiences some form of hallucinations.

Orientation and Cognition: The patient is usually oriented to time, place, and person unless driven by their delusion. Memory and cognition generally are not affected.

Risks: It is crucial to evaluate the patient for suicidal or homicidal ideation and plans. If there is a history of aggression with an adverse outcome, then hospitalization should be considered.

Insight and Judgment: Most commonly, patients and their partners have no insight into their mental illness. Judgment is assessable by inquiring about past behavior and a future plan.![]() [9][12][13]

[9][12][13]

Evaluation

As with any other psychiatric disorder, no specific labs are necessary for shared psychotic disorder. Most of the investigations, whether imaging or laboratory tests, should be considered to rule out any organic cause. A urine toxicology screen is vital to rule out any substance-induced disorder. If there are no organic or substance-induced disorders, a full psychiatric assessment should be next. It is helpful to ask for collateral history about both partners from a third person. It is common to take a history only from one of the partners because of strict social isolation, which can be very challenging. After taking a history, the psychiatrist should conduct a complete mental status examination. Collecting further details from other members of the family or friends should help in evaluating the patient. The primary partner can be defensive and misleading to encapsulate the delusion, concealing the symptoms for years.

Treatment / Management

Treatment should be tailored on a patient-by-patient basis. If there is an undertreated patient, efforts should be made to encourage increased adherence to the treatment plan. There have been suggestions that separation from the primary improves the condition significantly. After admission, the influence of the primary partner gradually disappears. However, it is worth noting that recent data suggest that separation by itself can be insufficient or may aggravate the condition.[3][14] Treating both partners with medication, whether alone (antipsychotics or antidepressant) or in combination (mood stabilizers and antipsychotics) and (antidepressants and antipsychotics), may help improve the condition.[3] Starting medication indicates that the patient's condition is severe and likely to express residual symptoms. It is critical to follow up with patients due to a possible alternative diagnosis. Psychotherapy can be offered to both partners either individually or as conjoined-psychotherapy.[7] Electroconvulsive therapy is an option.[3]

If there is an undertreated patient, efforts should be made to encourage increased adherence to the treatment plan. There have been suggestions that separation from the primary improves the condition significantly. After admission, the influence of the primary partner gradually disappears. However, it is worth noting that recent data suggest that separation by itself can be insufficient or may aggravate the condition.[3][14] Treating both partners with medication, whether alone (antipsychotics or antidepressant) or in combination (mood stabilizers and antipsychotics) and (antidepressants and antipsychotics), may help improve the condition.[3] Starting medication indicates that the patient's condition is severe and likely to express residual symptoms. It is critical to follow up with patients due to a possible alternative diagnosis. Psychotherapy can be offered to both partners either individually or as conjoined-psychotherapy.[7] Electroconvulsive therapy is an option.[3]

Differential Diagnosis

Formulating a differential diagnosis must include a history of the association between both partners. The onset of the condition usually precedes the onset of the shared delusion(s). The diagnosis of shared psychotic disorder should always be made only after ruling out any organic cause or substance-induced disorder.

The onset of the condition usually precedes the onset of the shared delusion(s). The diagnosis of shared psychotic disorder should always be made only after ruling out any organic cause or substance-induced disorder.

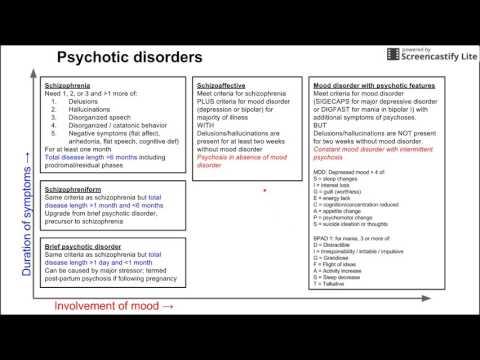

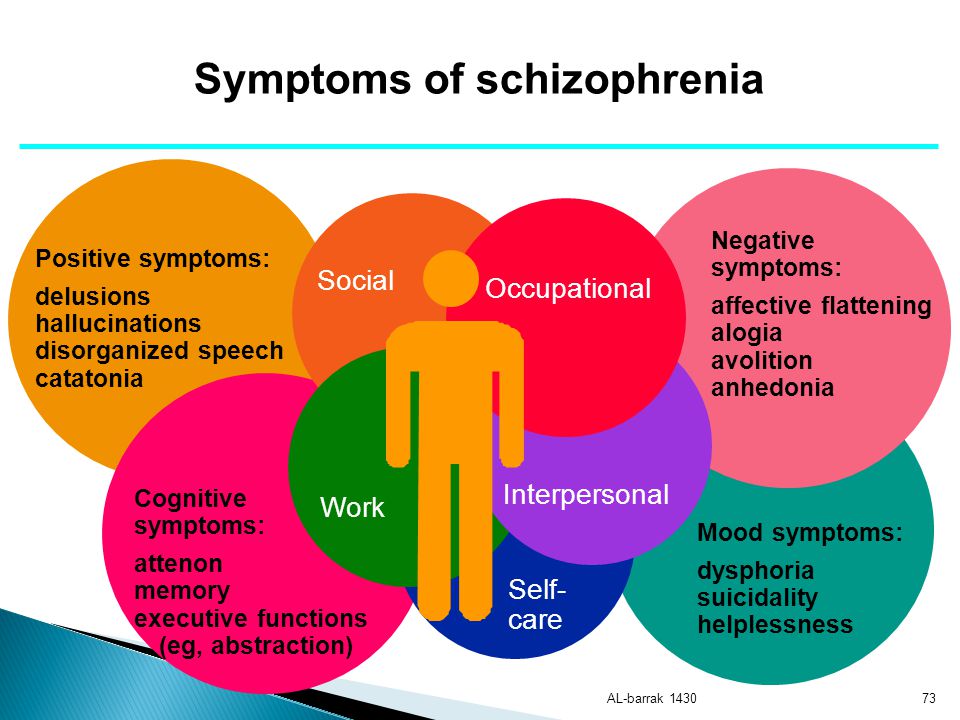

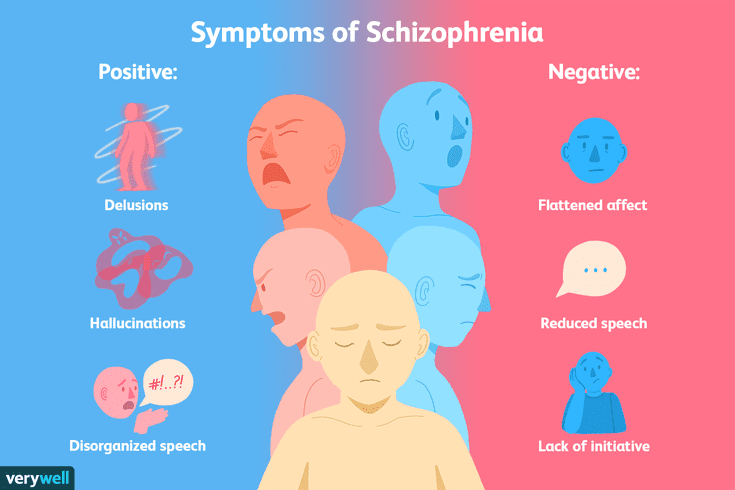

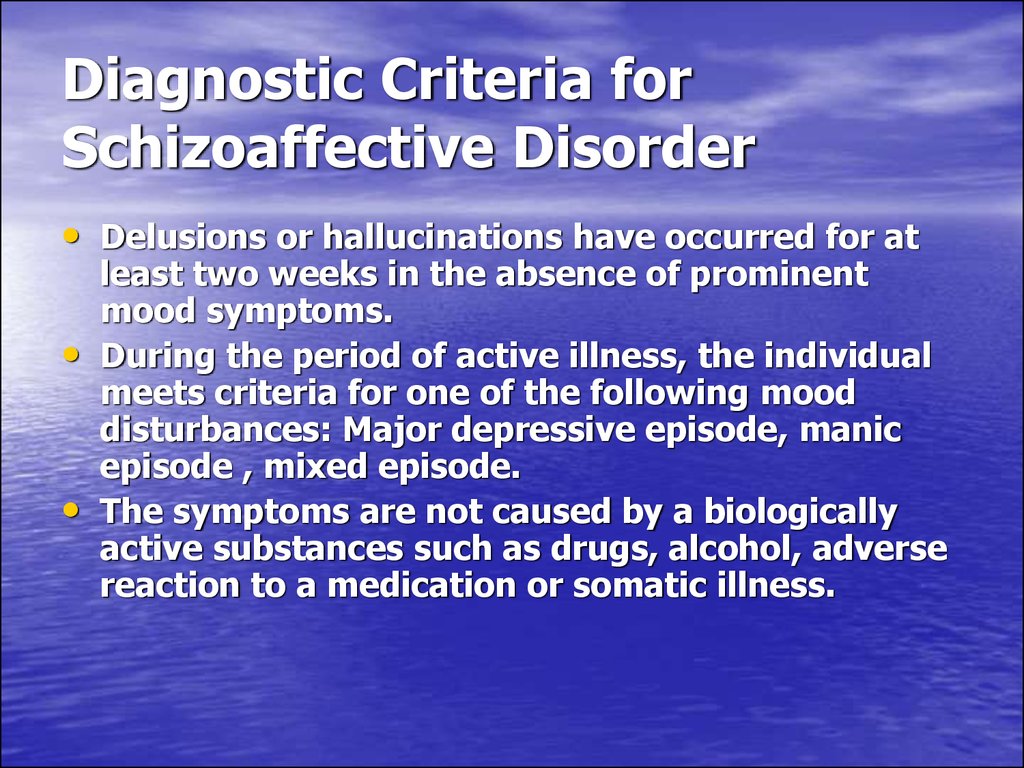

Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective: This can be differentiated by the secondary reporting symptoms that are not influenced by the primary, such as hallucinations, disorganized speech, or negative symptoms. In the case of schizoaffective, an affective component should be present.

Mood Disorder with Psychotic features: This condition has a specific delusion that is mood-congruent and not shared but expressed independently.

If the delusions do not disappear when the partners are separated, it is important to reassess and consider an alternative diagnosis.

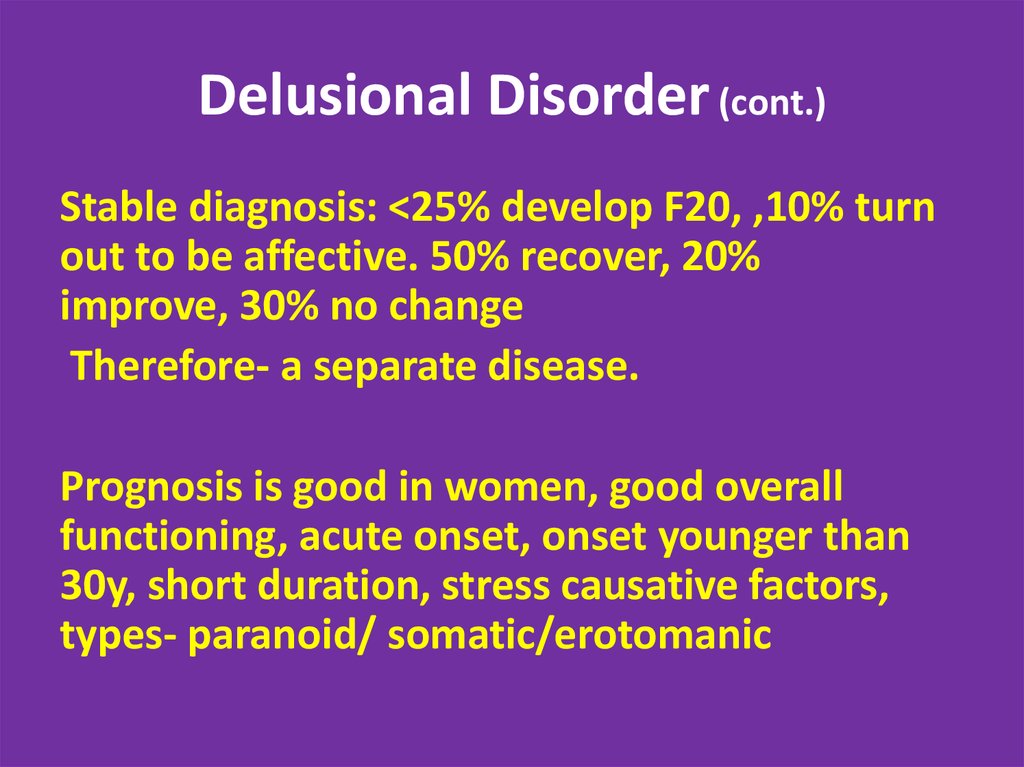

Prognosis

The prognosis of shared psychotic disorder is challenging to estimate, as it depends on multiple risk factors, including the primary's mental disorder and the secondary's biopsychosocial predisposing factors. Theoretically, children are more likely to benefit from separation than adults. Adherence to the management plan in both partners most likely will result in a better outcome than being untreated. An assessment of the nature and the duration of exposure to the delusion can provide clues to the potential outcomes of the disorder. Having premorbid personality features or predisposing risk factors can complicate the condition, leading one to consider an alternative diagnosis.[6]

Theoretically, children are more likely to benefit from separation than adults. Adherence to the management plan in both partners most likely will result in a better outcome than being untreated. An assessment of the nature and the duration of exposure to the delusion can provide clues to the potential outcomes of the disorder. Having premorbid personality features or predisposing risk factors can complicate the condition, leading one to consider an alternative diagnosis.[6]

Complications

These patients are not discovered easily due to a lack of insight. They are usually referred after a complication, namely acting on their delusions and jeopardizing their life or others. For example, a patient acts on their paranoid delusions via multiple accusations then commits an assault. Having delusions of grandeur or religious delusions also can be hazardous to others.[9]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients and their families may benefit from online resources. Websites often provide information about shared psychotic disorder along with information on support programs and resources. Additionally, any member of the healthcare team is well-positioned to educate patients and their families directly.

Additionally, any member of the healthcare team is well-positioned to educate patients and their families directly.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with shared psychotic disorder can go undiagnosed because only the primary partner is registered for treatment in a classic presentation. The level of tolerance and harmony among the two patients can add a significant challenge to the clinician in identifying each partner's role. Awareness of the nature of the dyad relationship dynamics is necessary. Most patients lack insight, which causes a substantial barrier to early discovery and management. The failure to adhere to treatment is an additional challenge to the clinician. A key aspect is understanding the impact of the delusions on both partners. A board-certified psychiatric pharmacist should work with the team to select the best agents for optimal therapeutic results with minimal adverse effects. A holistic approach that assesses and manages the biopsychosocial factors should help improve outcomes. The psychotherapist, mental health nurse, and psychiatrist should continue to follow these patients because relapse is common due to noncompliance with treatment.

The psychotherapist, mental health nurse, and psychiatrist should continue to follow these patients because relapse is common due to noncompliance with treatment.

Shared psychotic disorder requires a comprehensive interprofessional team approach that includes physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, working together as a team for optimal treatment and outcomes. [Level V]

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

Figure

The four types of Shared Psychotic Disorder (Folie à deux) by Alexander Gralnick (1942). Illustrations are contributed by Feras Al Saif, MBBCh

References

- 1.

Srivastava A, Borkar HA. Folie a famille. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;52(1):69-70. [PMC free article: PMC2824986] [PubMed: 20174522]

- 2.

Shimizu M, Kubota Y, Toichi M, Baba H. Folie à deux and shared psychotic disorder.

Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007 Jun;9(3):200-5. [PubMed: 17521515]

Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007 Jun;9(3):200-5. [PubMed: 17521515]- 3.

Arnone D, Patel A, Tan GM. The nosological significance of Folie à Deux: a review of the literature. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Aug 08;5:11. [PMC free article: PMC1559622] [PubMed: 16895601]

- 4.

Silveira JM, Seeman MV. Shared psychotic disorder: a critical review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 1995 Sep;40(7):389-95. [PubMed: 8548718]

- 5.

Lew-Starowicz M. Shared psychotic disorder with sexual delusions. Arch Sex Behav. 2012 Dec;41(6):1515-20. [PMC free article: PMC3501166] [PubMed: 22810994]

- 6.

Mentjox R, van Houten CA, Kooiman CG. Induced psychotic disorder: clinical aspects, theoretical considerations, and some guidelines for treatment. Compr Psychiatry. 1993 Mar-Apr;34(2):120-6. [PubMed: 8485980]

- 7.

Bankier RG. Role reversal in folie à deux. Can J Psychiatry. 1988 Apr;33(3):231-2. [PubMed: 3383097]

- 8.

Wehmeier P, Barth N, Remschmidt H. Induced delusional disorder. a review of the concept and an unusual case of folie à famille. Psychopathology. 2003 Jan-Feb;36(1):37-45. [PubMed: 12679591]

- 9.

Guivarch J, Piercecchi-Marti MD, Poinso F. Folie à deux and homicide: Literature review and study of a complex clinical case. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2018 Nov - Dec;61:30-39. [PubMed: 30454559]

- 10.

Kashiwase H, Kato M. Folie à deux in Japan -- analysis of 97 cases in the Japanese literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997 Oct;96(4):231-4. [PubMed: 9350949]

- 11.

Vigo L, Ilzarbe D, Baeza I, Banerjea P, Kyriakopoulos M. Shared psychotic disorder in children and young people: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019 Dec;28(12):1555-1566. [PubMed: 30328525]

- 12.

Salih MA. Suicide pact in a setting of Folie à Deux. Br J Psychiatry. 1981 Jul;139:62-7. [PubMed: 7296192]

- 13.

Joshi KG, Frierson RL, Gunter TD.

Shared psychotic disorder and criminal responsibility: a review and case report of folie à trois. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(4):511-7. [PubMed: 17185481]

Shared psychotic disorder and criminal responsibility: a review and case report of folie à trois. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(4):511-7. [PubMed: 17185481]- 14.

Talamo A, Vento A, Savoja V, Di Cosimo D, Lazanio S, Kotzalidis GD, Manfredi G, Girardi N, Tatarelli R. Folie à deux: double case-report of shared delusions with a fatal outcome. Clin Ter. 2011;162(1):45-9. [PubMed: 21448546]

Shared Psychotic Disorder - PubMed

Save citation to file

Format: Summary (text)PubMedPMIDAbstract (text)CSV

Add to Collections

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Name your collection:

Name must be less than 100 characters

Choose a collection:

Unable to load your collection due to an error

Please try again

Add to My Bibliography

- My Bibliography

Unable to load your delegates due to an error

Please try again

Your saved search

Name of saved search:

Search terms:

Test search terms

Email: (change)

Which day? The first SundayThe first MondayThe first TuesdayThe first WednesdayThe first ThursdayThe first FridayThe first SaturdayThe first dayThe first weekday

Which day? SundayMondayTuesdayWednesdayThursdayFridaySaturday

Report format: SummarySummary (text)AbstractAbstract (text)PubMed

Send at most: 1 item5 items10 items20 items50 items100 items200 items

Send even when there aren't any new results

Optional text in email:

Create a file for external citation management software

Full text links

StatPearls [Internet]

NCBI BookshelfFull text links

Book

Feras Al Saif 1 , Yasir Al Khalili 2

In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan.

Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan.

.

Affiliations

Affiliations

- 1 Psychiatric Hospital - Bahrain

- 2 Virginia Commonwealth University

- PMID: 31095356

- Bookshelf ID: NBK541211

Free Books & Documents

Book

Feras Al Saif et al.

Free Books & Documents

In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan.

.

Authors

Feras Al Saif 1 , Yasir Al Khalili 2

Affiliations

- 1 Psychiatric Hospital - Bahrain

- 2 Virginia Commonwealth University

- PMID: 31095356

- Bookshelf ID: NBK541211

Excerpt

Shared psychotic disorder (folie à deux) is a rare disorder characterized by sharing a delusion among two or more people in a close relationship. The inducer (primary) who has a psychotic disorder with delusions influences another nonpsychotic individual or more (induced, secondary) based on a delusional belief. It is commonly seen among two individuals, but in rare cases, can include larger groups. For example, it can occur in a family and is called folie à famille.

It is commonly seen among two individuals, but in rare cases, can include larger groups. For example, it can occur in a family and is called folie à famille.

Jules Baillarger was the first to report this condition in 1860. During the 19th century, psychiatrists in Europe suggested different names. In France, it has been called "folie communiquee"(communicated psychosis) by Baillarger. In German psychiatry, it was named "Induziertes Irresein" by Lehman and Sharfetter. In 1877 Lasegue and Falret coined the term “folie à deux.” The French word “folie à deux" means madness shared by two. In the early 1940s, Gralnick, in his review of 103 cases of folie à deux, described four types of this disorder. He defined it as a psychiatric entity characterized by the transfer of delusions from one person to one or several others who have a close association with the primarily affected person. The four types are as follows:

Folie imposee (imposed psychosis) - Described by Lasegue and Falret in 1877. The delusions are transferred from an individual with psychosis to an individual without psychosis in an intimate relationship. The delusions in the induced individual soon disappear once the two are separated.

Folie simultanee (simultaneous psychosis) - Described by Regis in 1880. Both partners share the psychosis simultaneously. They both have risk factors through long social interactions that predispose them to develop this condition. There are reports of sharing genetic risk factors among siblings.

Folie communiquée (communicated psychosis) - Described by Marandon de Montyel in 1881. This type is similar to folie imposee; however, the delusion in the secondary partner occurs after a long period of resistance. Also, the secondary partner will maintain the delusion even after separation from their partner.

Folie induite (induced psychosis) - Described by Lehmann in 1885. In this type, new delusions are assumed by an individual with psychosis who is being influenced by another individual with psychosis.

This disorder was first listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III) as shared paranoid disorder. In the next edition (DSM-IV), the term changed to shared psychotic disorder. In the latest edition, DSM-5, it was removed as a separate disease entity. It now is included in the section on other specified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. ICD-10 lists it as induced delusional disorder.

Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Sections

- Continuing Education Activity

- Introduction

- Etiology

- Epidemiology

- Pathophysiology

- History and Physical

- Evaluation

- Treatment / Management

- Differential Diagnosis

- Prognosis

- Complications

- Deterrence and Patient Education

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

- References

Similar articles

-

[Folie à deux in schizophrenia--"psychogenesis" revisited].

Shimizu M. Shimizu M. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2004;106(5):546-63. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2004. PMID: 15230353 Japanese.

-

Shared Psychotic Disorder (Folie À Deux): A Rare Case with Dissociative Trance Disorder That Can Be Induced.

Saragih M, Amin MM, Husada MS. Saragih M, et al. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019 Aug 20;7(16):2701-2704. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.821. eCollection 2019 Aug 30. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019. PMID: 31777640 Free PMC article.

-

Folie à Deux in the Setting of COVID-19 Quarantine.

Baez Nuñez M, Rodriguez E, DeLuca M, Chirimunj K, Dhingra M. Baez Nuñez M, et al. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2022 Apr 20;2022:2046436. doi: 10.1155/2022/2046436.

eCollection 2022. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2022. PMID: 35492235 Free PMC article.

eCollection 2022. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2022. PMID: 35492235 Free PMC article. -

Coexistence of folie communiquée and folie simultanée.

Tényi T, Somogyi A, Hamvas E, Herold R, Vörös V, Trixler M. Tényi T, et al. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2006;10(3):220-2. doi: 10.1080/13651500600579365. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2006. PMID: 24941061

-

De Clérambault Syndrome, Othello Syndrome, Folie à Deux and Variants.

Delgado MG, Bogousslavsky J. Delgado MG, et al. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2018;42:44-50. doi: 10.1159/000475685. Epub 2017 Nov 17. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2018. PMID: 29151090 Review.

See all similar articles

References

-

- Srivastava A, Borkar HA.

Folie a famille. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;52(1):69-70. - PMC - PubMed

Folie a famille. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;52(1):69-70. - PMC - PubMed

- Srivastava A, Borkar HA.

-

- Shimizu M, Kubota Y, Toichi M, Baba H. Folie à deux and shared psychotic disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007 Jun;9(3):200-5. - PubMed

-

- Arnone D, Patel A, Tan GM. The nosological significance of Folie à Deux: a review of the literature. Ann Gen Psychiatry.

2006 Aug 08;5:11. - PMC - PubMed

2006 Aug 08;5:11. - PMC - PubMed

- Arnone D, Patel A, Tan GM. The nosological significance of Folie à Deux: a review of the literature. Ann Gen Psychiatry.

-

- Silveira JM, Seeman MV. Shared psychotic disorder: a critical review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 1995 Sep;40(7):389-95. - PubMed

-

- Lew-Starowicz M. Shared psychotic disorder with sexual delusions. Arch Sex Behav. 2012 Dec;41(6):1515-20. - PMC - PubMed

Publication types

Full text links

StatPearls [Internet]

NCBI BookshelfCite

Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Send To

Delusional disorder - symptoms, causes, stages

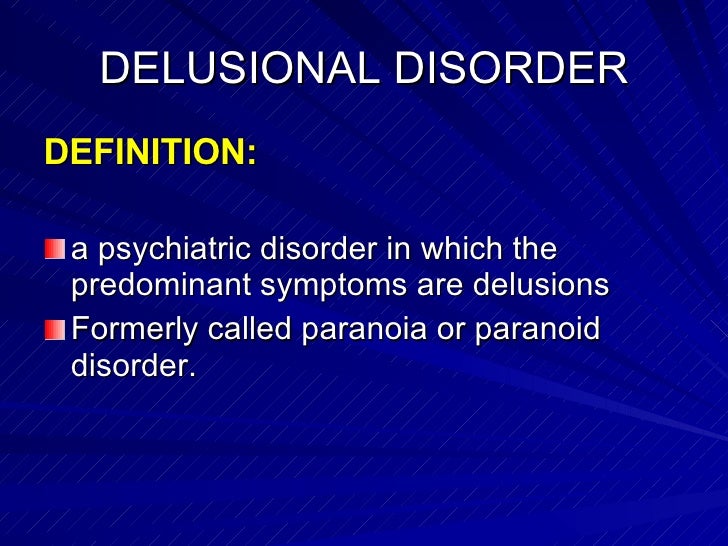

Delusion or chronic delusional disorder refers to a person's false beliefs based on a misinterpretation of reality.

Although delusions can occur as part of other psychiatric disorders (such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), a diagnosis of delusional mental disorder is made only when delusional thoughts are the main and main symptom of the disease.

Disease definition

Delusional disorder (ICD-10 code F22.0) is defined as a psychotic personality disorder in which a person has difficulty recognizing reality, resulting in delirium.

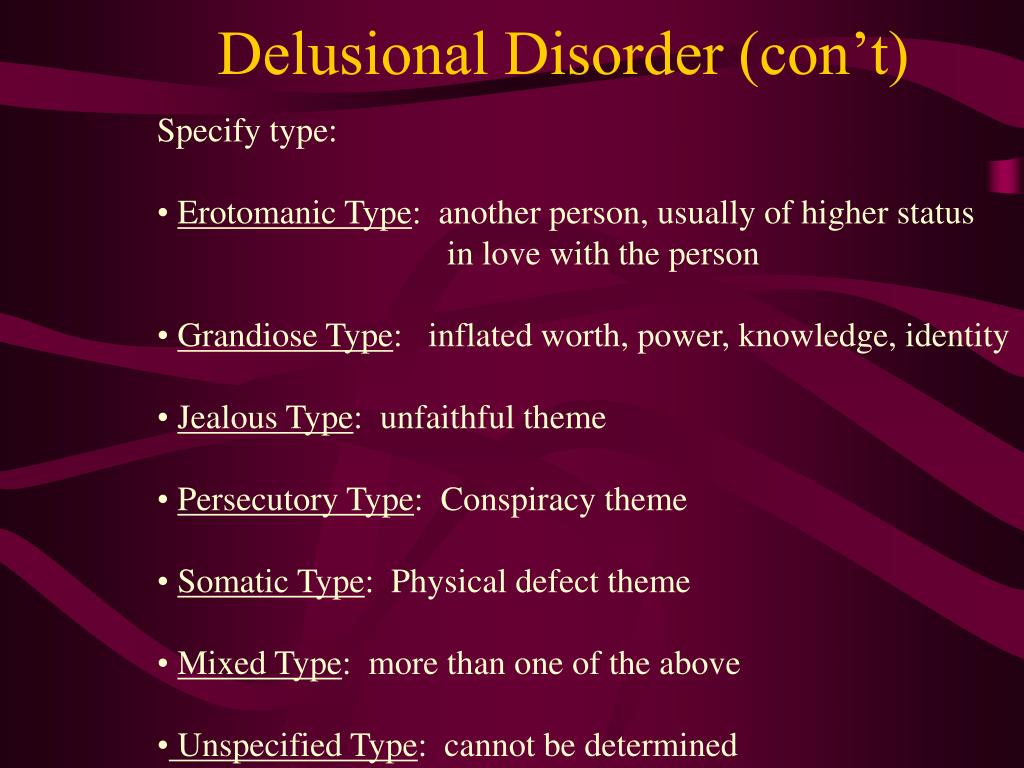

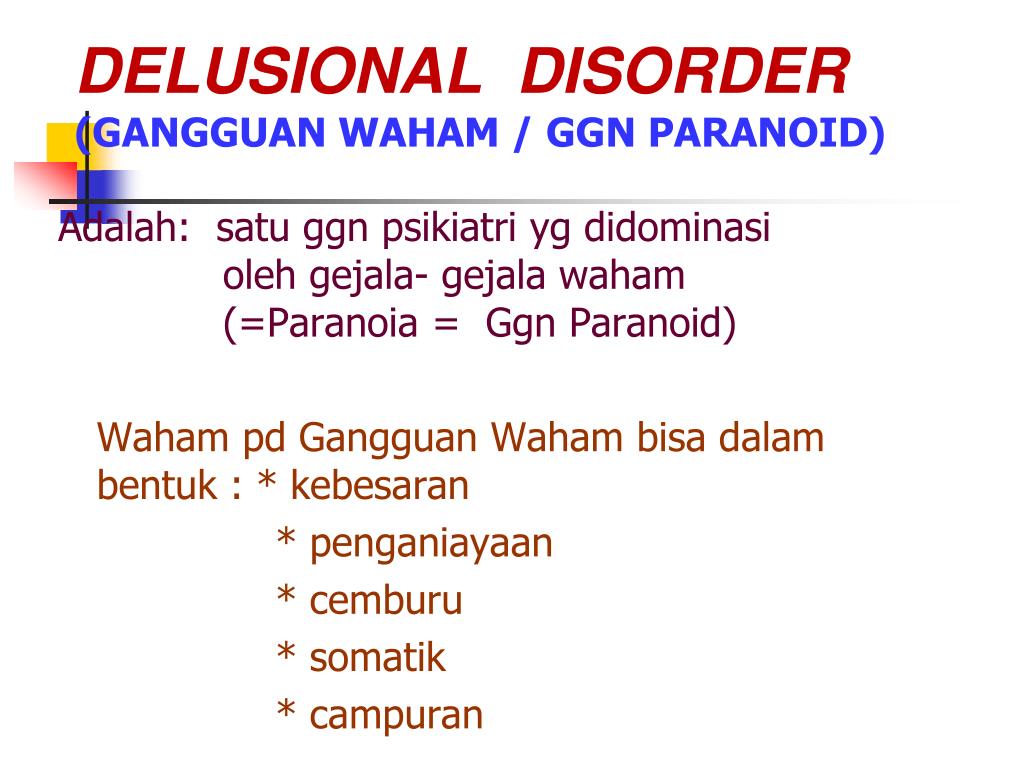

Sufferers of this disease firmly hold false beliefs despite clear evidence to the contrary. Their crazy ideas can be very diverse. The most common in delusional thought disorder are:

- delusions of grandeur, in which one's own importance is overestimated;

- delusion of guilt, when a person believes that he has committed a terrible serious crime;

- delusions of jealousy with a predominance of the idea of committing adultery by a partner;

- delusions of insertion and translation of thoughts, in which it seems that other people's thoughts are inserted into the person's mind;

- somatic delusions, characterized by a belief in the presence of serious diseases and damage to internal organs;

- delusions of persecution, when it seems that a person is being followed and a cruel crime is planned against him;

- erotic or love delirium, characterized by the presence of thoughts that someone is in love with the patient;

- litigious (Querulant) nonsense consists in a stubborn struggle for one's fictitious rights, which are allegedly violated.

There is also the concept of hypochondriacal delusional disorder, in which a person who has become disillusioned with medicine develops his own system of treatment and, thanks to it, “recovers”. Then he can promote it and “treat” other people who believe him.

Induced delusional disorder is a personality disorder in which delusions are shared by two or more persons with close emotional ties (eg, relatives).

The sick person's delusions may include circumstances that are impossible or unlikely in life. At the same time, delusional thoughts do not interfere with general logical reasoning and usually do not cause serious behavioral disorders.

People with delusional psychotic disorder usually do not have hallucinations or mood disorders. And if hallucinations do occur, they are part of a delusional belief. For example, a patient who has a delusion that his internal organs are rotting may hallucinate smells or sensations that are directly related to this delusion.

Symptoms of delusional personality disorder

The main symptom of a delusional disorder is the presence of strange, delusional thoughts in a person, which persist steadily for 3 months. Brad, at the same time, is built logically and internally consistent.

The main features of chronic delusional disorder include:

- A person suffering from a delusional disorder expresses his belief or idea with extraordinary persistence and force.

- His delusions are unlikely and do not correspond to social, cultural and religious status. Those who know the patient well argue that his beliefs and behavior are uncharacteristic and alien.

- Delusional thoughts have an excessive impact on a person's life, as a result of which his lifestyle often changes beyond recognition.

- The patient with delusional personality disorder becomes overly sensitive, especially about his beliefs, and also loses his sense of humor.

- Although he is deeply convinced of his delusional ideas, he can become secretive and suspicious, especially when asked about his beliefs.

- An attempt to refute a belief or idea causes an inappropriately strong emotional reaction in the patient, accompanied by irritability and hostility.

- Delusions, if enacted, often result in abnormal and non-characteristic behavior.

Causes of Delusional Personality Disorder

The primary cause of delusional disorder is not exactly known. However, genetic, biochemical and environmental factors can play a decisive role in its development.

The main causes of this disease include:

- biological factors. Brain abnormalities or chemical imbalances in the brain, traumatic brain injury, severe infectious disease, and alcohol and substance abuse can all contribute to organic delusional disorder.

- Hereditary predisposition. This disease is more common in people who have relatives with mental illness (schizophrenia or delusional personality disorder).

- Social factors. Social isolation, immigration, unemployment, low socioeconomic status can also be risk factors for the onset of the disease.

- Cultural and religious factors. As a result of their influence, a person may develop spiritual, magical and religious delusions.

- Old age and dementia. Delusional disorders in dementia are quite common. This is explained by the occurrence of a number of mental and behavioral disorders in the syndrome of senile dementia.

- Impaired hearing or vision. Studies have shown that people with hearing or vision impairments are at a higher risk of developing psychosis and delusional states. One explanation is that hearing or vision impairments can lead to misinterpretations of the environment, causing people to perceive the world around them differently.

- Serious traumatic situation, chronic exposure to stress.

Neurobiological factors play a key role in the pathogenesis of chronic delusional disorder.

Dysregulation of dopamine and other neurotransmitters is known to be associated with certain symptoms of this disease. Dopamine is a hormone and neurotransmitter that modulates motor control, motivation, and reward. Therefore, dysregulation of dopaminergic activity in the brain (namely, the occurrence of hyperactivity of dopamine receptors in some areas of the brain and underactivity in others) can lead to symptoms of acute delusional psychotic disorder.

There is also a psychological theory of the occurrence of delusional disorder. It's called the defense mechanism theory. It is hypothesized that delusions are the result of a defense mechanism aimed at maintaining a positive view of oneself by attributing negative properties to other people or circumstances.

Stages and classification of delusional personality disorder

There are two main stages of delusional personality disorder:

- Acute delusional disorder.

An acute condition begins unexpectedly (for example, after a head injury or meningitis). It is characterized by the brightness and severity of symptoms.

An acute condition begins unexpectedly (for example, after a head injury or meningitis). It is characterized by the brightness and severity of symptoms. - Chronic stage. This degree of delusional disorder is characterized by a slow development of the disease with irreversible changes. As a rule, they are discovered late, and some deviations in the patient's behavior are attributed to character traits or age.

In Russian psychiatric practice, it is customary to distinguish several types of delusional disorder:

- Paranoia (paranoid personality disorder). The main feature of this condition is the presence of a chronic and pervasive distrust and suspicion of the patient towards the people around him. People with this disorder feel like everyone around them is lying. Patients are characterized by outbursts of anger, excessive control in relationships, negativism, sensitivity to criticism.

- Late paraphrenia (involutional delusional disorder) - the common name for delusional psychoses that occur for the first time in adulthood (45-55 years), for a long time proceeding without pronounced personality changes.

Characterized by the presence of paraphrenic delusions with fantastic ideas (usually delusions of grandeur or persecution). This type of delusional disorder is considered more severe than paranoia. It can be described as an intermediate link between paranoia and schizophrenia.

Characterized by the presence of paraphrenic delusions with fantastic ideas (usually delusions of grandeur or persecution). This type of delusional disorder is considered more severe than paranoia. It can be described as an intermediate link between paranoia and schizophrenia. - Paranoid schizophrenia with sensitive delusions of attitude. This is a disease with slowly developing and long-term delusions that do not develop into psychosis. Refers to delusional schizophrenia-like disorders. It manifests itself in the pathological beliefs of the patient that something that excites him in himself is also noticed by those around him. To some extent, this phenomenon is characteristic of most healthy, but shy people, especially those suffering from a physical inferiority complex. They themselves are constantly focused on such thoughts and are too afraid to discover some real, but greatly exaggerated shortcoming. However, with this type of disorder, these manifestations become overly pronounced.

The attribution of people suffering from these symptoms to patients with schizophrenia causes a lot of doubt and controversy.

The attribution of people suffering from these symptoms to patients with schizophrenia causes a lot of doubt and controversy. - Other delusional disorder. This category includes: delusional dysmorphophobia, involutional paranoid state and querulant paranoia. Delusional dysmorphophobia is characterized by the patient's dissatisfaction with their appearance and delusional ideas about it. The involutional paranoid state is an senile paranoia that develops in adulthood and old age. The main manifestation of the involutionary paranoid is everyday delirium. Querulant paranoia is manifested by litigious activity, expressed in the struggle for one's rights and infringed interests (often imaginary or exaggerated).

Complications of delusional disorder

With inadequate medical treatment and the absence of a stable remission, the consequences of a chronic delusional disorder can be as follows:

- depressed mood;

- sleep disorders;

- depression;

- inability to build normal social contacts, love and family relationships;

- unemployment;

- decrease in the socio-economic standard of living;

- aggressiveness, causing harm to others;

- dangerous behavior.

The most serious complication of delusional disorder is the occurrence of suicidal thoughts and suicide.

The risk group for the occurrence of delusional disorders includes, first of all, persons of mature and elderly age with dementia, visually impaired and deaf, sensitive people with "magical thinking", as well as those who are in social isolation.

If they have unlikely delusions, false beliefs, strange behavior, suspicion, secrecy and distrust, you should definitely consult a doctor.

The sooner treatment, including pharmacotherapy, is started, the more favorable the prognosis will be. In addition, it will be possible to avoid many complications that affect both the patient himself and his family and environment.

Diagnosis of delusional mental disorder

Since the disease "delusional personality disorder" is quite rare, the doctor, first of all, evaluates the possibility of the patient having other serious mental illnesses with similar symptoms.

Differential diagnosis of delusional disorder is also carried out in order to exclude suspicions of the somatic nature of the disease. With similar symptoms, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease, brain tumors, epilepsy and others can occur.

The age of the patient must be taken into account. Older people who develop dementia often become delusional.

Diagnosis of a delusional disorder can be difficult if the patient hides his thoughts, and relatives brought him to the doctor. Since the victim is convinced of the reality of his ideas, he may refuse to accept his diagnosis and be treated.

The attending physician may prescribe various diagnostic tests of the brain, such as electroencephalography, magnetic resonance or computed tomography.

Treatment of delusional personality disorder

Treatment of delusional disorder is a responsible task for the doctor, the patient and his relatives.

People with this disorder usually do not admit that their beliefs or ideas are delusional and therefore rarely seek medical help. It is quite difficult for a doctor to establish contact and a therapeutic relationship with them.

It is quite difficult for a doctor to establish contact and a therapeutic relationship with them.

The most effective treatment for the disorder is drug therapy with antipsychotics. Antipsychotic drugs help to stop psychotic symptoms and “interrupt” delusions by acting on dopamine and serotonin receptors in the brain.

Given that delusional states of the disorder usually develop in late adulthood, the most rational treatment is the use of atypical antipsychotics. Improvement after starting antipsychotics usually occurs within 3-4 weeks.

Treatment for delusional disorders can be done on an outpatient basis or in a hospital setting. In severe cases of delusional disorder, when medical treatment does not help, electroconvulsive therapy can be used by decision of the council of doctors, and with the consent of the patient and his relatives.

Psychotherapy may be used as supportive treatment. Its purpose is to promote adherence to the treatment regimen, as well as to ensure sufficient awareness of the disease. In this case, individual rather than group psychotherapy is recommended, since patients with delusional disorders are often suspicious and sensitive.

In this case, individual rather than group psychotherapy is recommended, since patients with delusional disorders are often suspicious and sensitive.

+7 (495) 121-48-31

Prevention or advice in case of illness

Prevention of delusional disorder consists in maintaining a healthy psychological environment in the family, dealing with stress, maintaining a healthy lifestyle, as well as seeking medical help in a timely manner if any symptoms of mental disorders occur.

Recommendations for delusional disorder:

- Make sure that the patient takes the prescribed medication in a timely manner and visits the attending physician.

- If psychotic symptoms worsen, delirium, insomnia, and behavioral disturbances (aggression and irritability), seek medical attention to adjust treatment.

- Tune in to positive communication with the patient, be patient, do not argue with him, pretend to agree. Be clear about your thoughts and ask simple questions.

Pressure or criticism from others will lead the person to severe stress, which can exacerbate the symptoms of delusional disorders.

Pressure or criticism from others will lead the person to severe stress, which can exacerbate the symptoms of delusional disorders.

References:

- Yu. V. Popov, V. D. Vid. Modern clinical psychiatry. - M .: Expert Bureau-M, 1997.

- Banshchikov V.M., Korolenko Ts.P., Davydov I.V. General psychopathology. - M .: Moscow Medical Institute. THEM. Sechenov, 1971.

- McWilliams, Nancy. Paranoid Personalities // Psychoanalytic Diagnosis: Understanding Personality Structure in the Clinical Process = Psychoanalyticdiagnosis: Understandingpersonalitystructureintheclinicalprocess. - M .: Class, 1998.

Treatment of delusional disorder | Cochrane

Delusional disorder is a mental illness in which long-term perceptual delusions (strange beliefs) are the only or main symptom. There are several types of perceptual delusions. Some may make the suffering person feel that they are being persecuted, or may cause anxiety that they have a disease they do not have. People may have delusions of grandeur, such that they believe they are high position or famous. Perceptual delusions may also include the jealousy of others, or include bizarre ideas about body image, such as that they have a certain bodily defect.

People may have delusions of grandeur, such that they believe they are high position or famous. Perceptual delusions may also include the jealousy of others, or include bizarre ideas about body image, such as that they have a certain bodily defect.

Delusional disorders are considered difficult to treat. Antipsychotic medications, antidepressants, and mood stabilizing drugs are often used to treat this mental illness, and there is growing interest in psychological therapies such as psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as treatments.

This review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of all available treatments for people with delusional disorder. A search for randomized controlled trials was performed in 2012. The authors found 141 citations in the search, but only one trial randomizing 17 people could be included in the review. The study compared the effectiveness of CBT with supportive psychotherapy in people with delusional disorder. Participants were already taking medication and continued during the trial. The review could not include any studies or trials involving drugs of any kind for the treatment of delusional disorder.

The review could not include any studies or trials involving drugs of any kind for the treatment of delusional disorder.

For the study that was included, there was limited information that we could use. It was difficult to draw firm conclusions, and evidence for improving people's behavior and overall physical health was not available. More people left the study early in the supportive psychotherapy group, but the number of participants was small and the overall difference between the groups was not sufficient to conclude that one treatment was better than the other. A positive effect of CBT has been found in relation to people's social self-assertion, although again, these results are limited by the low quantity and quality of data and are not relevant to people's social or daily functioning.

At present, there is a general lack of high quality, evidence-based information about the treatment of delusional disorder and insufficient evidence to make recommendations for treatment of any kind.