Prodromal psychosis symptoms

Understanding the schizophrenia prodrome - PMC

Indian J Psychiatry. 2017 Oct-Dec; 59(4): 505–509.

doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_464_17

,,,, and

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

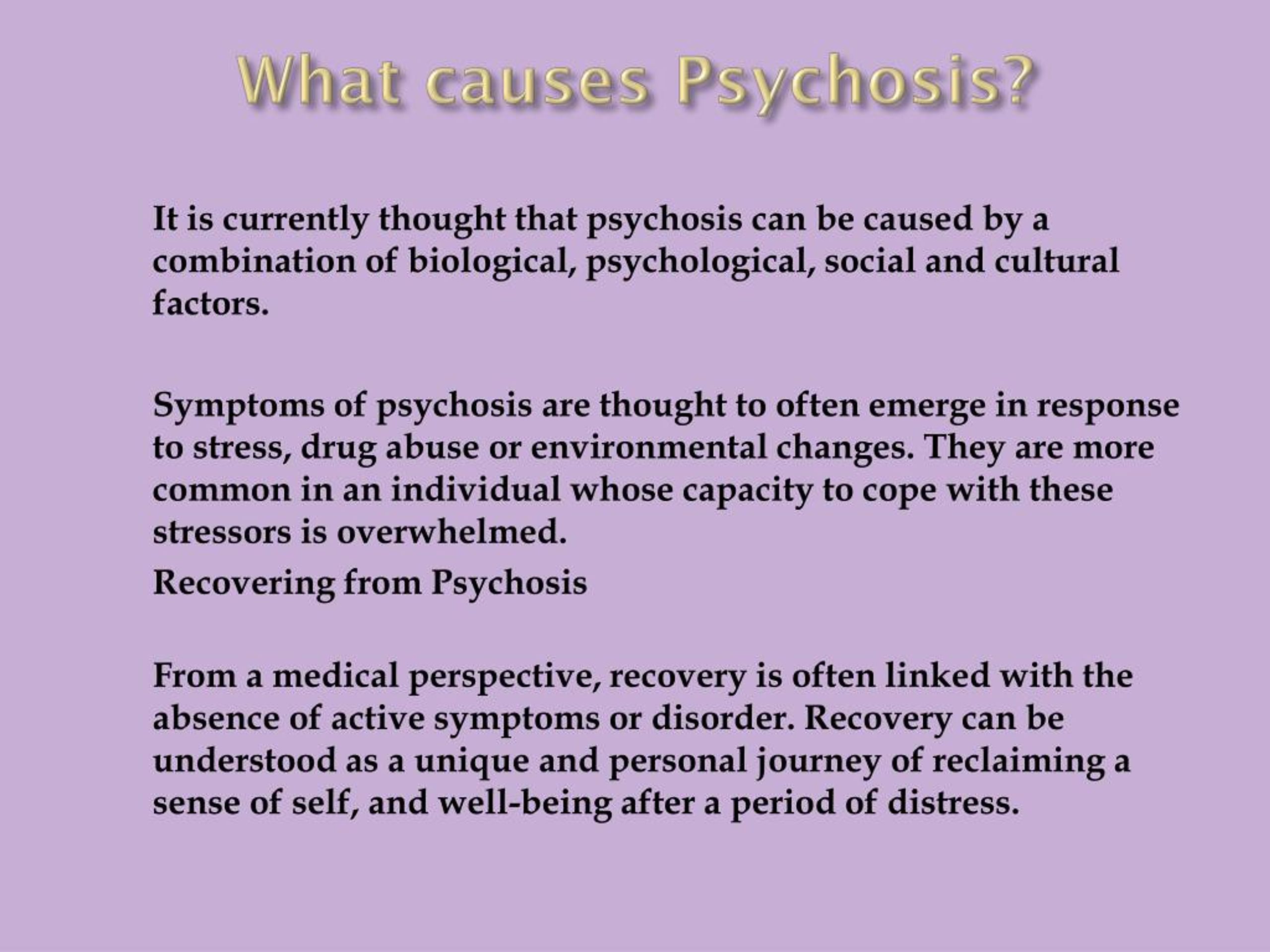

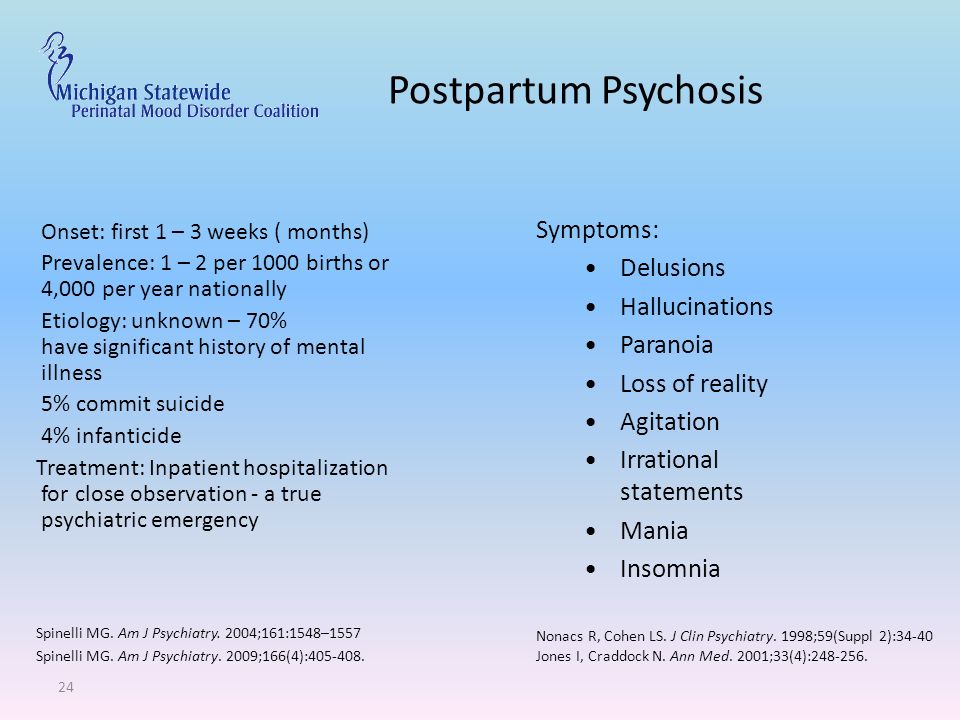

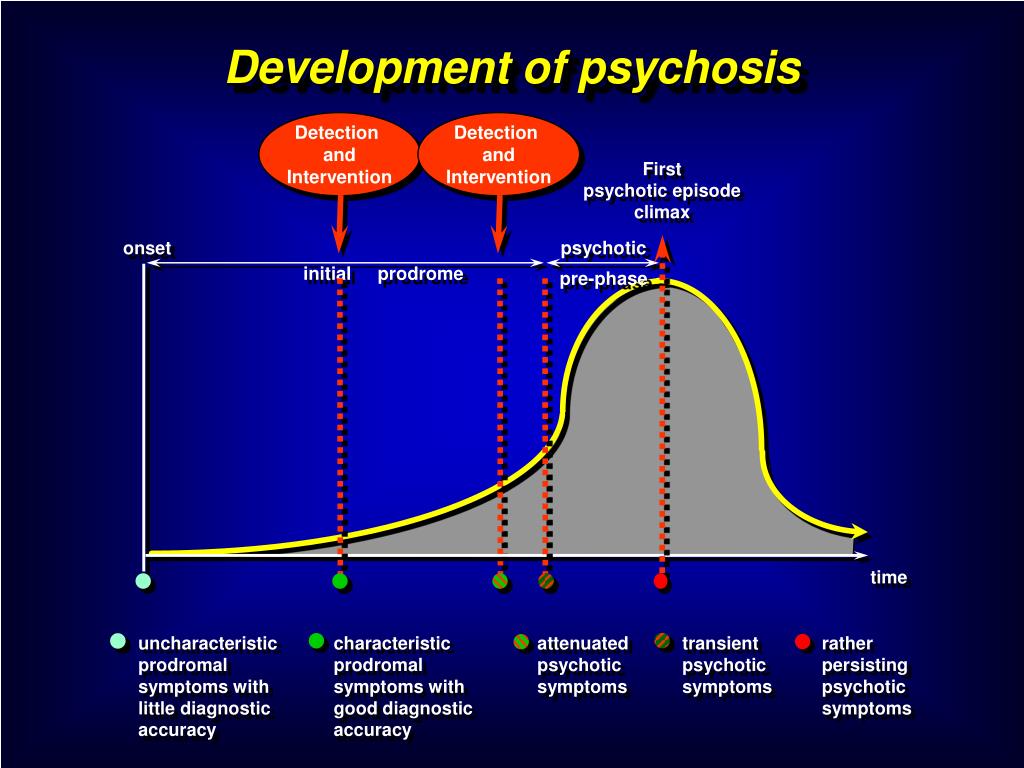

Schizophrenia is a neurodevelopmental disorder and its course is said to have an onset much before the presentation with psychotic symptoms. Even though the concept of prodrome in schizophrenia has been accepted, there is still an existence of a diagnostic dilemma. Various imaging studies and biomarkers have also been studied for confirmation of this diagnosis. The critical period of intervention when identified clarifies the doubts about faster and better outcomes.

Keywords: Neurodevelopmental disorder, prodrome, psychosis, schizophrenia

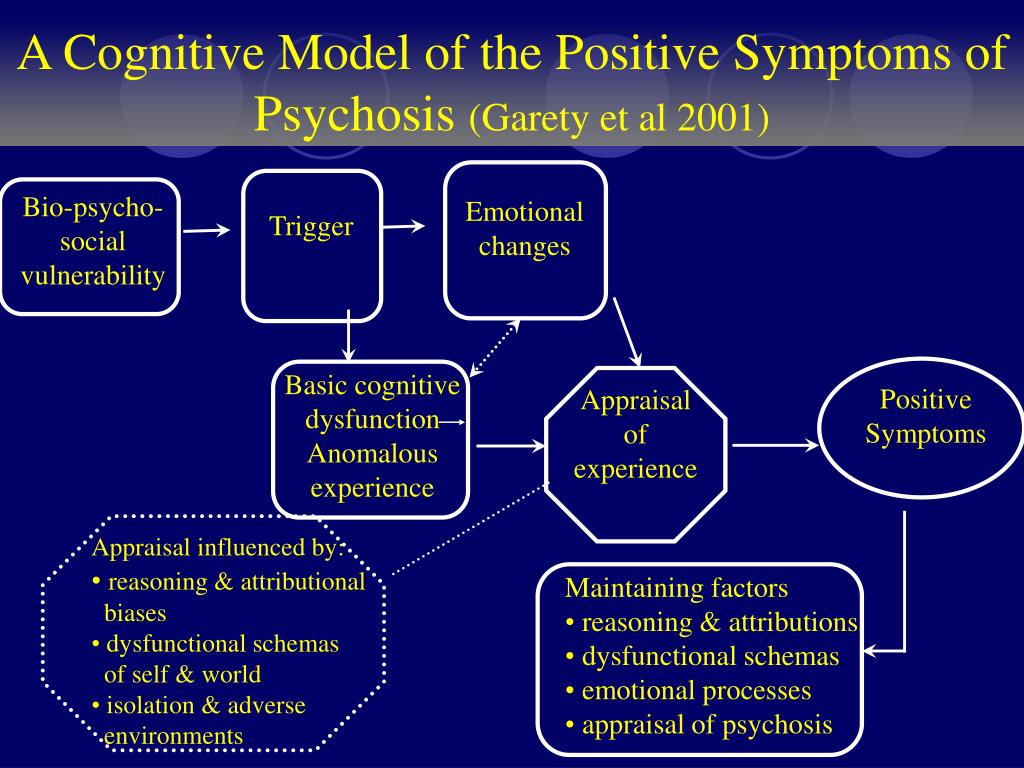

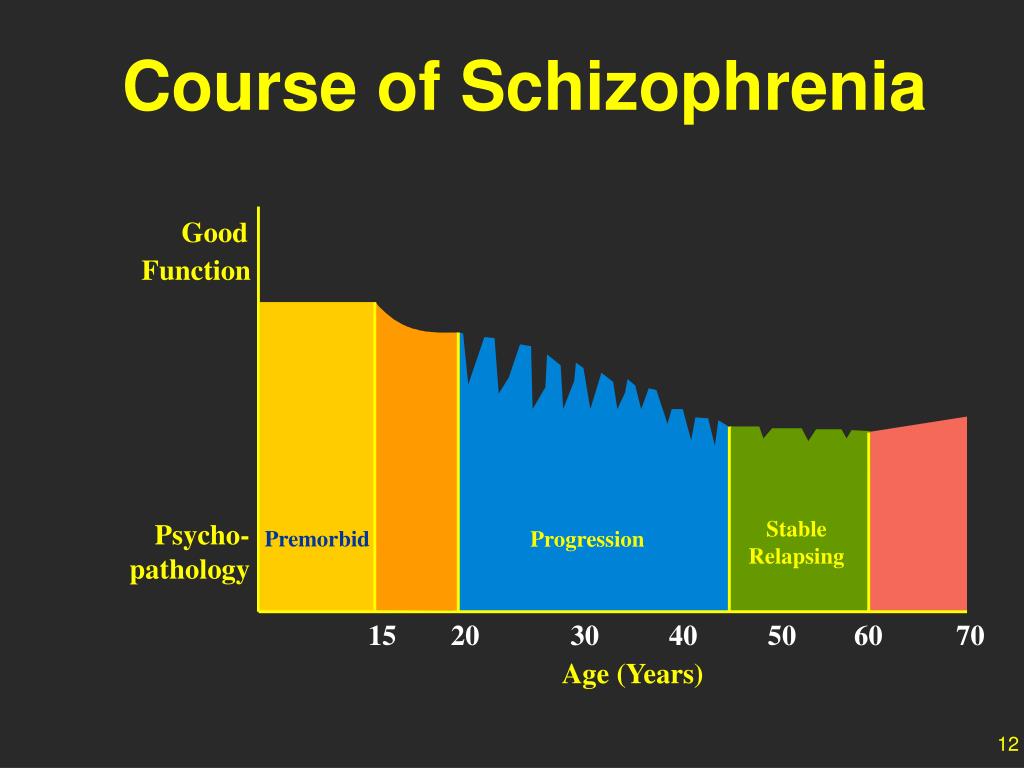

The evolution of the concept of schizophrenia dates back to the 1850s when Kraepelin delineated symptomatology which shared a common course and outcome and called it as dementia precox. Later, Bleuler coined the term “schizophrenia” describing it as a group of psychosis having a variable and chronic course.[1,2,3] There is extensive evidence that schizophrenia is a neurodevelopmental disorder and its course unfolds throughout life. Starting from genetic and environmental factors, it will eventually lead to deficits in neural systems hampering the functions of substrates critical for assessment of sensory input, cognitive functions, and information processing.[3,4] The widespread acceptance of the neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia has not been able to throw light on the much debated prodromal phase of the illness.[5]

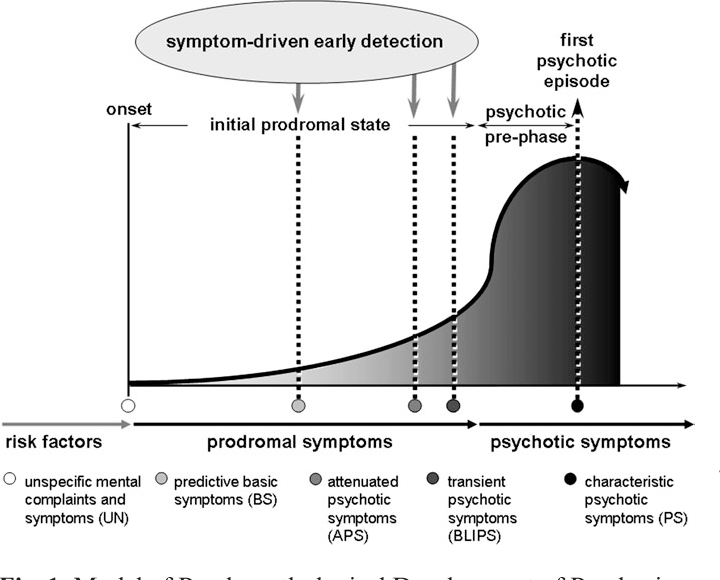

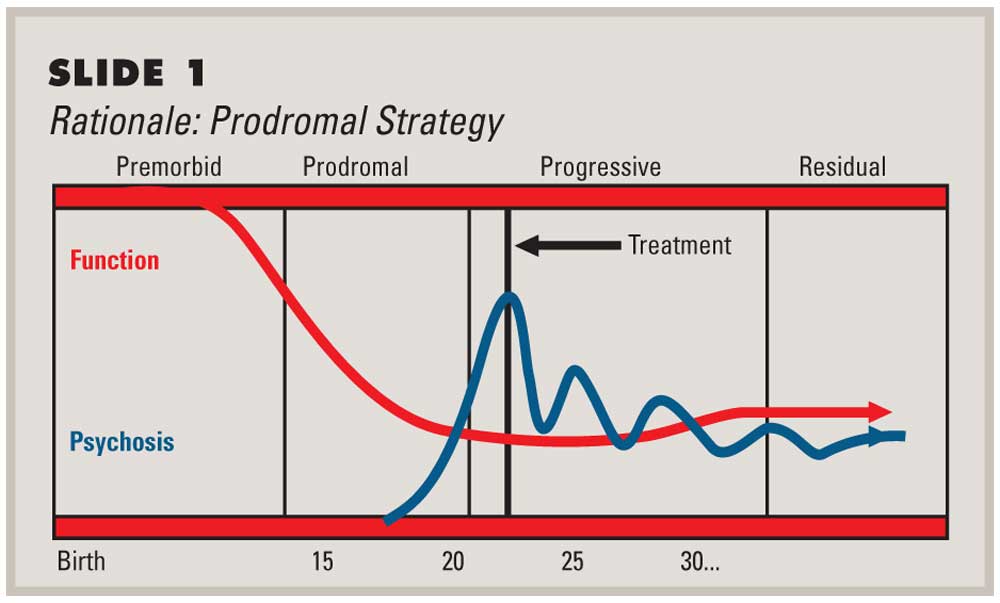

It was Bleuler in 1911, who first gave the concept that changes in a person who develops schizophrenia can be identified as a prodromal phase.[6] Accurate depiction of the prodrome can help identify individuals who may be at risk of impending psychosis. Appreciating the first manifestations of the subtle changes and intervening at the particular state with antipsychotic medication may be associated with a better prognosis in the long-term outcome of the disease. Several other studies have suggested the use of antidepressants or anti-anxiety drugs to alleviate symptoms in a person who may be at risk. According to recent developments, a prodromal state may be identified based on the current symptoms with reliability and predictive validity. Appreciation is growing that these patients and their families experience substantial current distress.[7] Thus, current symptoms provide another rationale for intervention research in addition to the need for research targeting the prevention of schizophrenia.

Several other studies have suggested the use of antidepressants or anti-anxiety drugs to alleviate symptoms in a person who may be at risk. According to recent developments, a prodromal state may be identified based on the current symptoms with reliability and predictive validity. Appreciation is growing that these patients and their families experience substantial current distress.[7] Thus, current symptoms provide another rationale for intervention research in addition to the need for research targeting the prevention of schizophrenia.

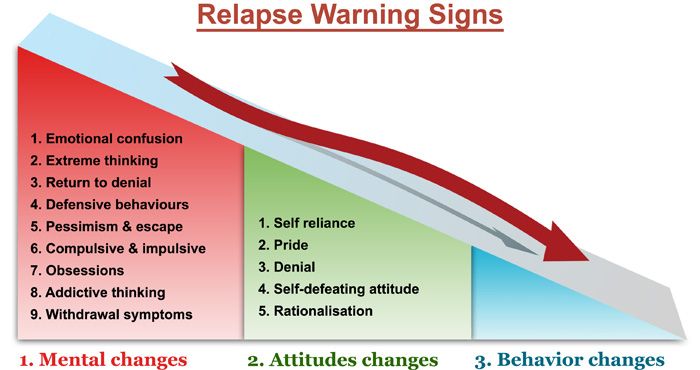

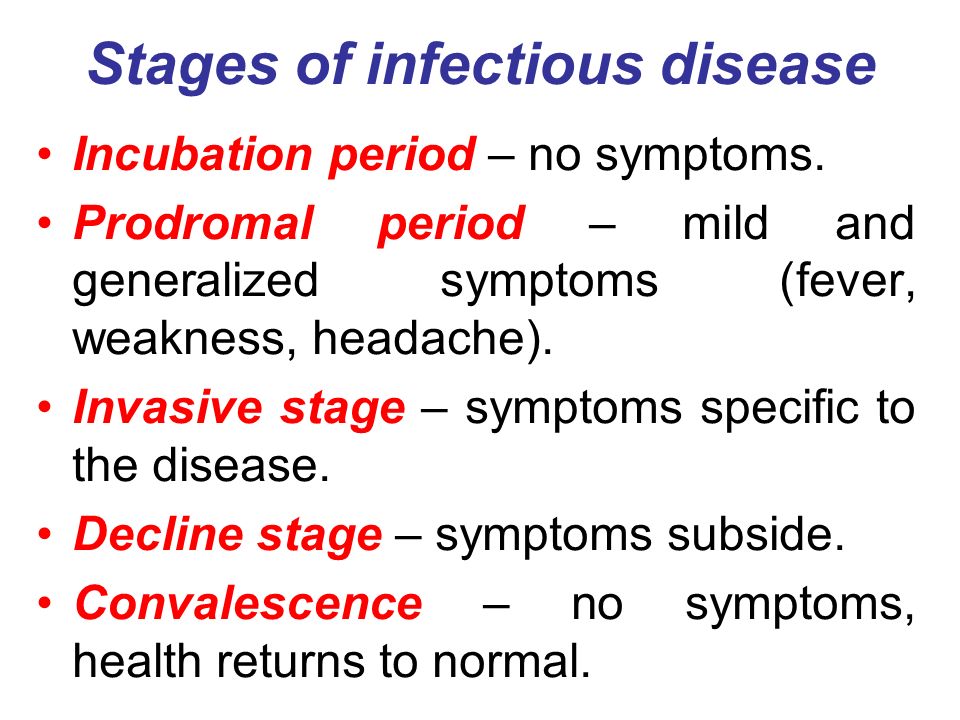

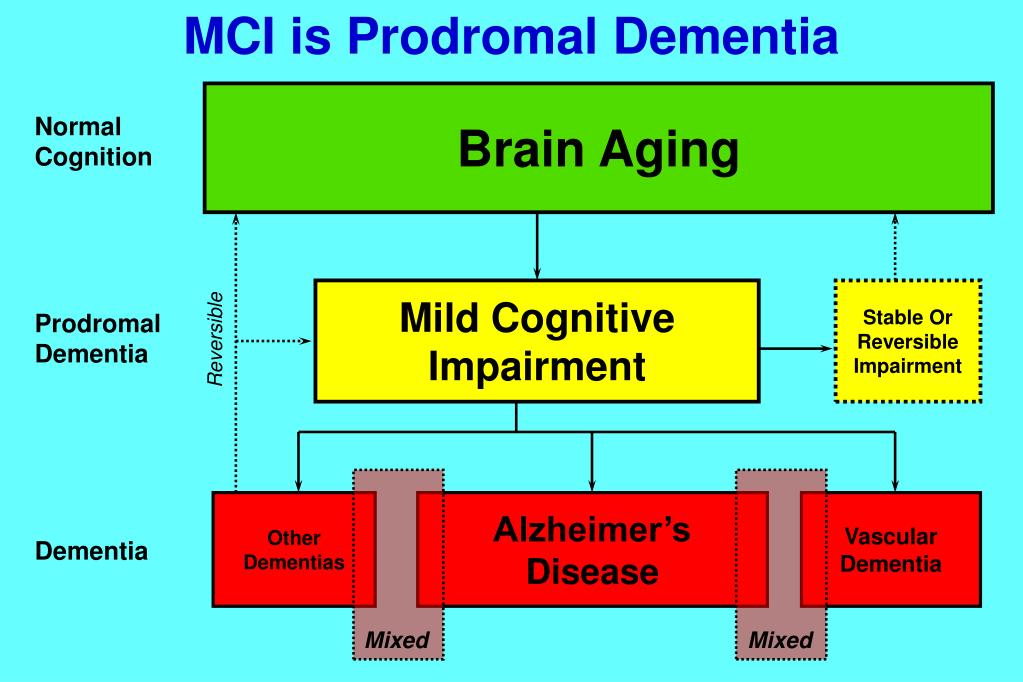

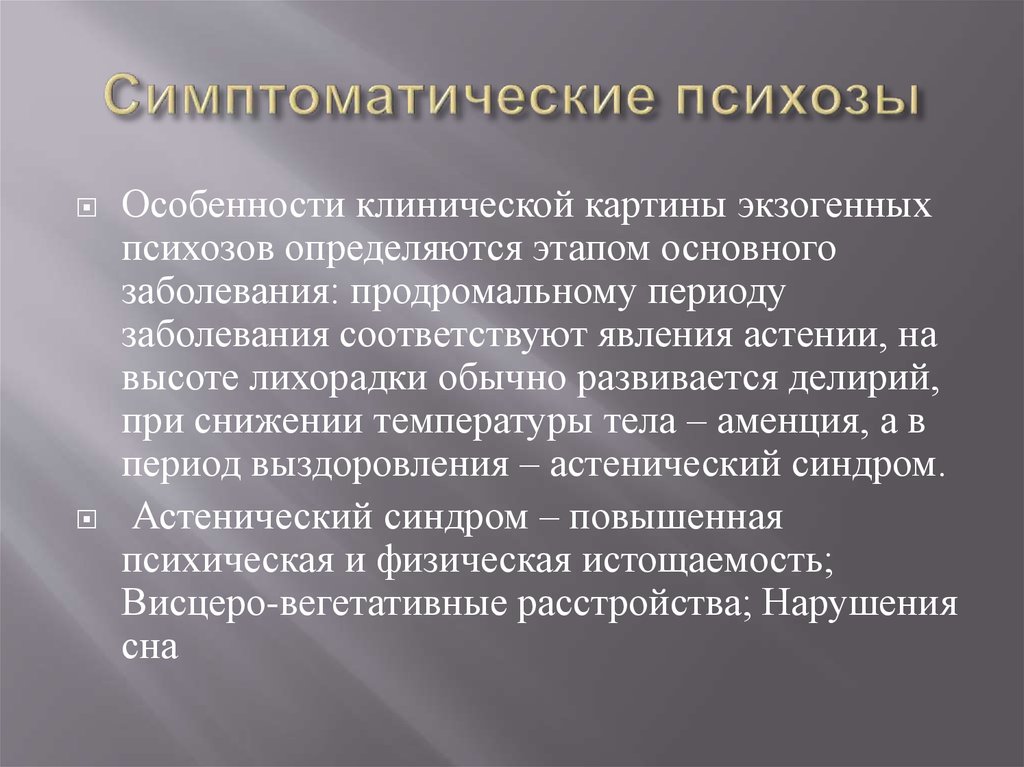

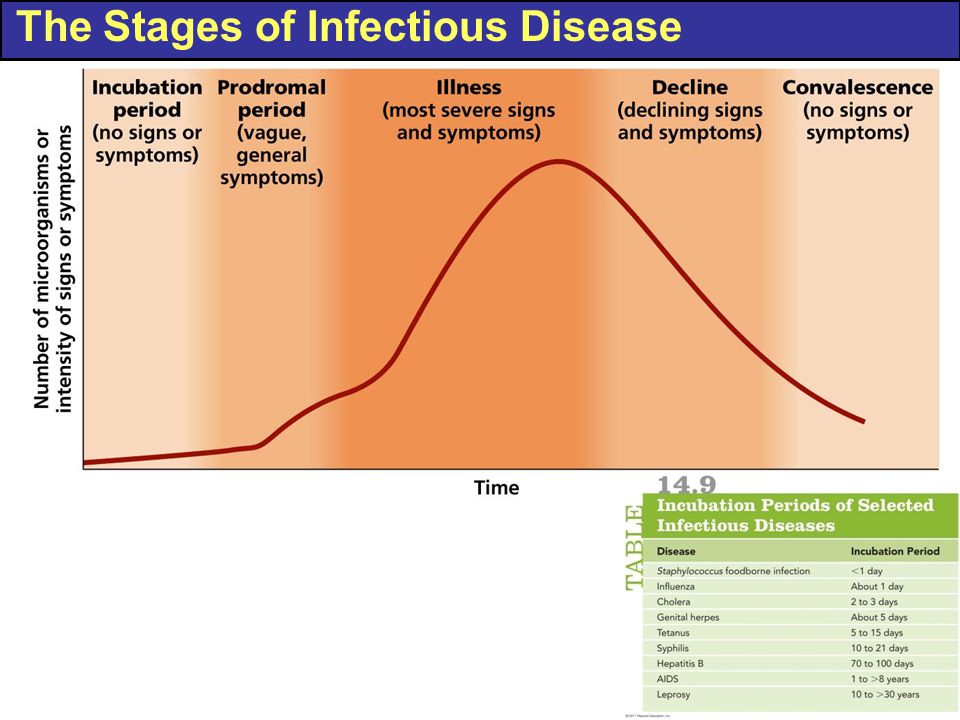

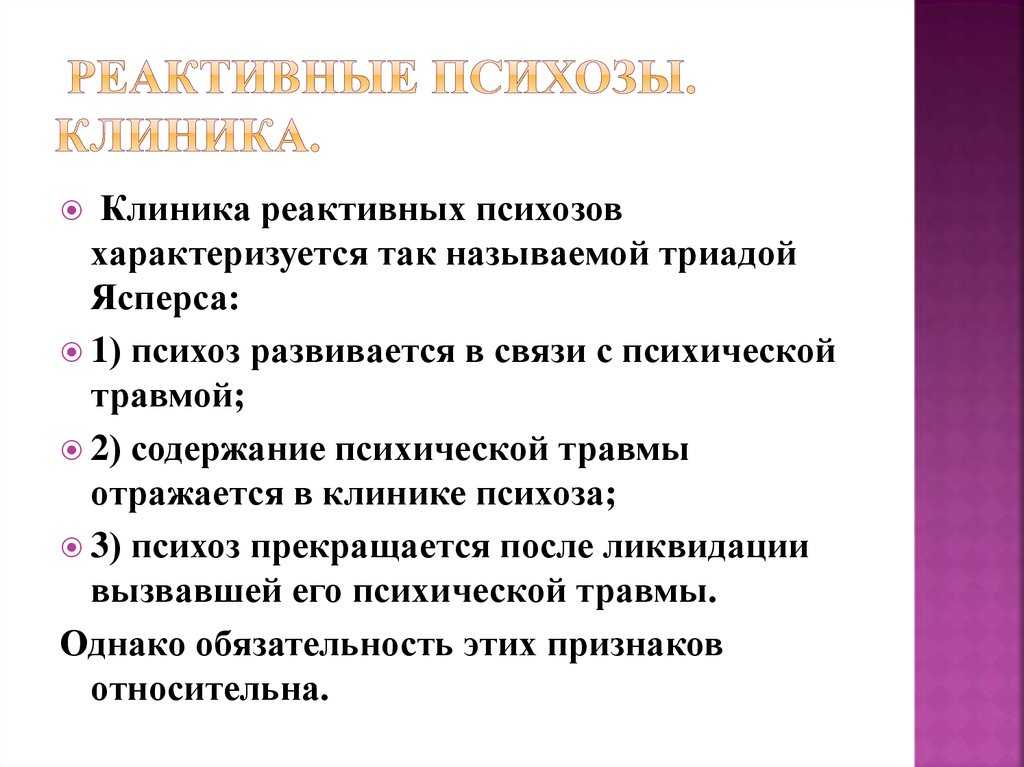

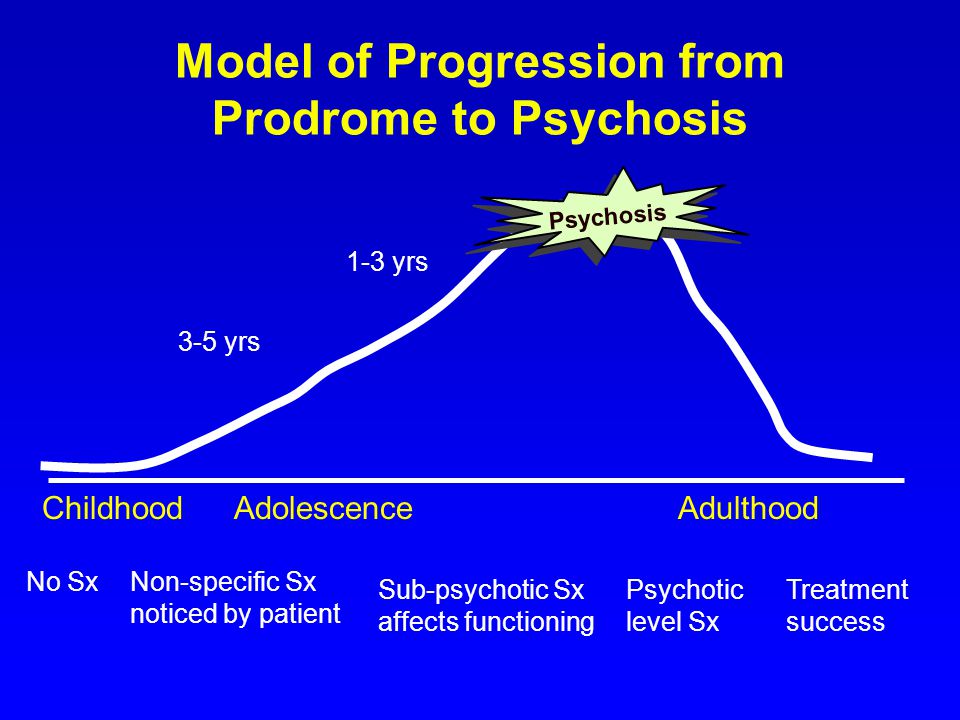

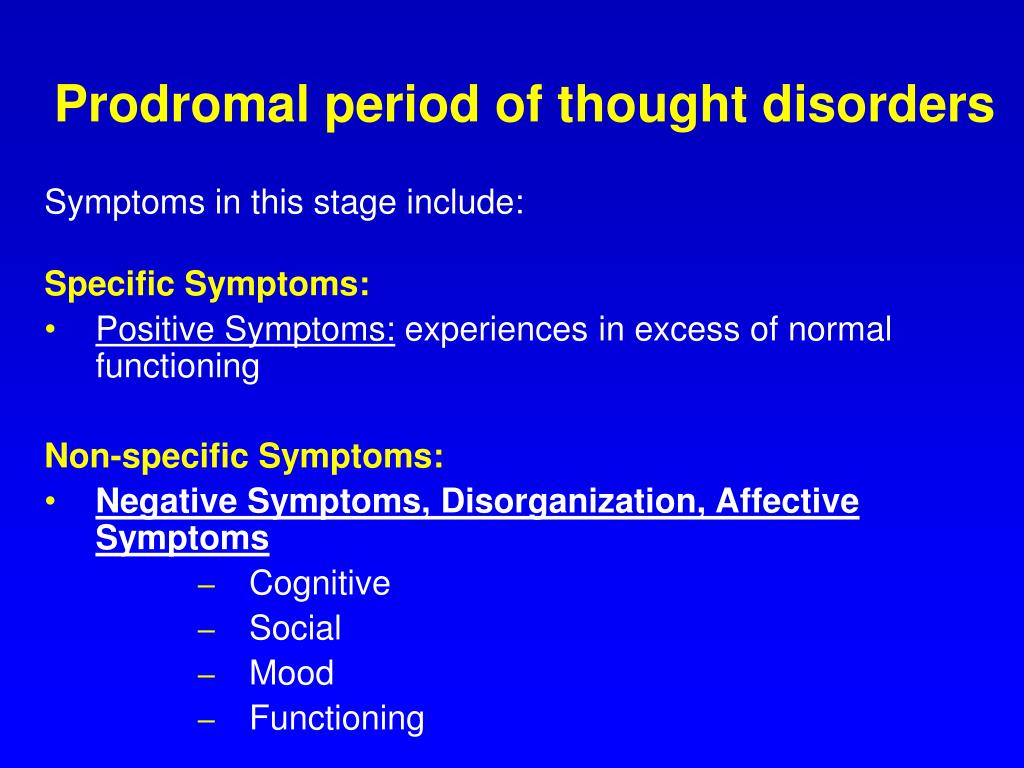

Prodrome in clinical medicine refers to the early symptoms and signs of illness preceding the characteristic manifestations. In psychiatry, it is referred to as “the initial prodrome” and “relapse prodrome.” The widely accepted definition of prodrome was given by Keith and Matthews in 1991 as a “heterogeneous group of behaviors temporally related to the onset of psychosis. Loebel et al. (1992) defined it as the time interval from the onset of unusual behavioral symptoms to onset of psychotic symptoms[8] and Beiser

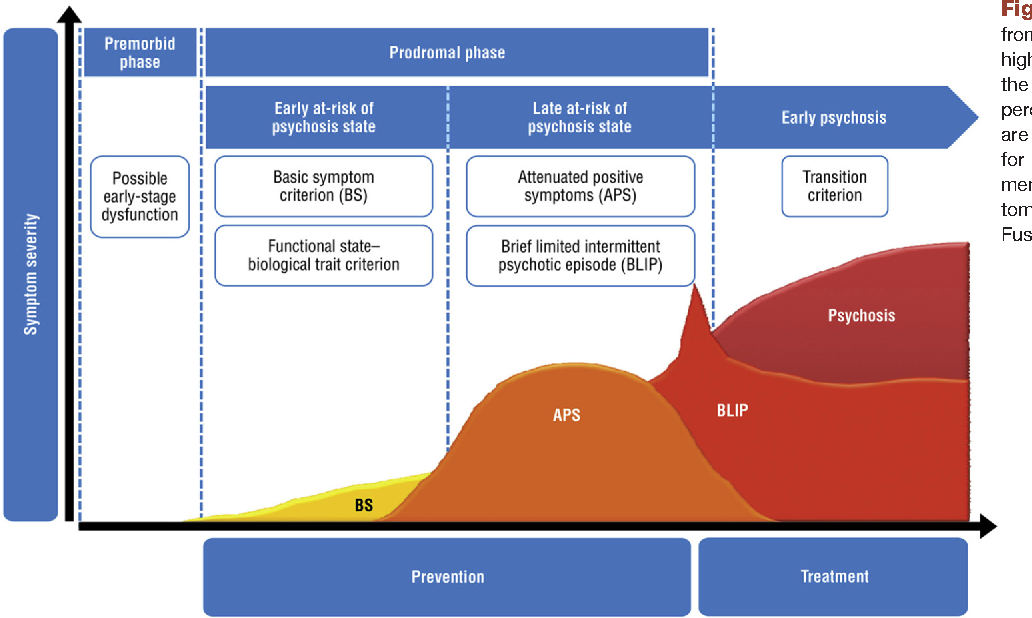

et al. (1993) defined it as the period from first noticeable symptoms to first prominent psychotic symptoms.[9] The concept of prodrome does not refer to a hardbound set of signs and symptoms. It is an evolution over time. Docherty et al. in 1978 described it as a “moment to moment march of psychological changes.” The evolution of prodrome has been categorized into two main patterns. Pattern 1 was described as certain nonspecific changes, followed by specific prepsychotic symptoms, and then eventually leading to psychosis. Pattern 2 explains the evolution to begin with early specific changes followed by neurotic symptoms as a reaction to these and then psychosis. Chapman in 1978 described 5 patterns of disturbances which are disturbances in attention, perception, speech production, motor functions, and thought block. From the above-mentioned symptoms, disturbance in motility occurs secondary to disturbance of attention and perception.[10] Huber et al. coined the term “basic symptoms” which can be subjective complaints of emotional, cognitive, or autonomic impairment.

(1993) defined it as the period from first noticeable symptoms to first prominent psychotic symptoms.[9] The concept of prodrome does not refer to a hardbound set of signs and symptoms. It is an evolution over time. Docherty et al. in 1978 described it as a “moment to moment march of psychological changes.” The evolution of prodrome has been categorized into two main patterns. Pattern 1 was described as certain nonspecific changes, followed by specific prepsychotic symptoms, and then eventually leading to psychosis. Pattern 2 explains the evolution to begin with early specific changes followed by neurotic symptoms as a reaction to these and then psychosis. Chapman in 1978 described 5 patterns of disturbances which are disturbances in attention, perception, speech production, motor functions, and thought block. From the above-mentioned symptoms, disturbance in motility occurs secondary to disturbance of attention and perception.[10] Huber et al. coined the term “basic symptoms” which can be subjective complaints of emotional, cognitive, or autonomic impairment. Another consideration was “symptomatic psychosis at-risk state” which finally paved way to the ultrahigh risk (UHR) criteria which was set at a high threshold in an attempt to reduce misdiagnosis among psychiatrists.[11,12] This is in contrast to at-risk mental state (ARMS) which defines a syndrome that may or may not develop into psychosis. A person at ARMS may manifest symptoms such as depressed mood, anxiety, and psychosis but may not necessarily meet UHR criteria. The finding of duration of untreated psychosis and early intervention at this particular point has provided a new insight into the etiopathological progress of the illness.[13] Studies have indicated better socio-occupational functioning in patients who have received intervention.[13,14,15] Although the boundary between the ARMS and actual psychosis might be narrow and vaguely demarcated,[16] “close-in” follow-up strategy, which involves shortening the periods of follow-up helps us to observe the transition to psychosis.

Another consideration was “symptomatic psychosis at-risk state” which finally paved way to the ultrahigh risk (UHR) criteria which was set at a high threshold in an attempt to reduce misdiagnosis among psychiatrists.[11,12] This is in contrast to at-risk mental state (ARMS) which defines a syndrome that may or may not develop into psychosis. A person at ARMS may manifest symptoms such as depressed mood, anxiety, and psychosis but may not necessarily meet UHR criteria. The finding of duration of untreated psychosis and early intervention at this particular point has provided a new insight into the etiopathological progress of the illness.[13] Studies have indicated better socio-occupational functioning in patients who have received intervention.[13,14,15] Although the boundary between the ARMS and actual psychosis might be narrow and vaguely demarcated,[16] “close-in” follow-up strategy, which involves shortening the periods of follow-up helps us to observe the transition to psychosis.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)-III-R (American Psychiatric Association 1987) focuses mainly on observable behavioral changes in its description of the prodromal features of schizophrenia. It provides an operationalized criteria of nine symptoms for schizophrenic prodrome:[17]

It provides an operationalized criteria of nine symptoms for schizophrenic prodrome:[17]

Marked social isolation or withdrawal

Marked impairment in role functioning

Markedly peculiar behavior

Marked impairment in personal hygiene and grooming

Blunted or inappropriate affect

Digressive, vague, overelaborate or circumstantial speech, or poverty of speech, or poverty of content of speech

Odd beliefs or magical thinking

Unusual perceptual experiences

Marked lack of initiative, interests, or energy.

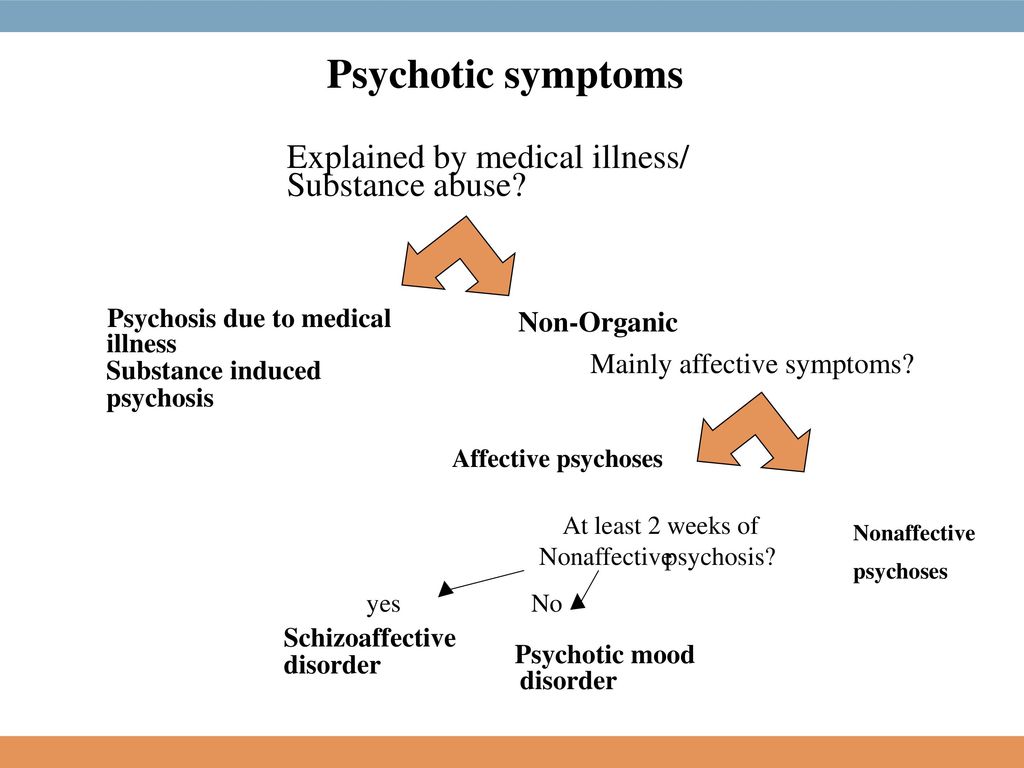

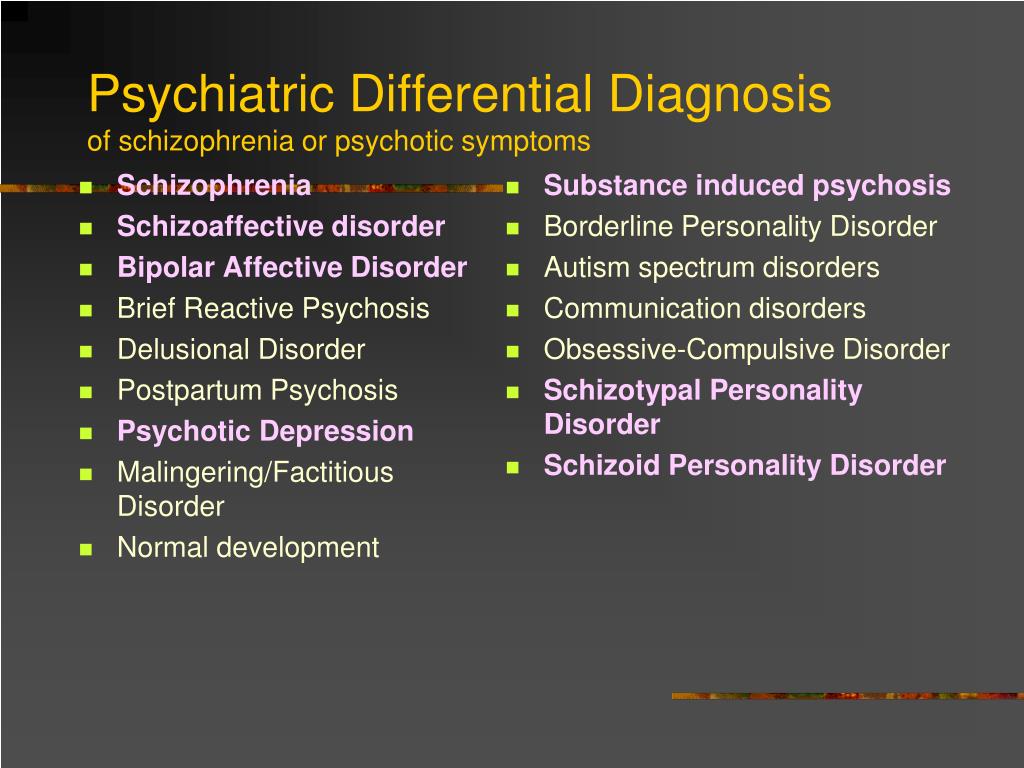

This list of criteria has been dropped from the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994). The International classification of diseases (ICD)-10 (World Health Organization 1994) acknowledges a prodrome as part of the schizophrenic syndrome; prodromal symptoms are not included in its description of schizophrenia (Keith and Matthews 1991). The whole picture of this prodromal phase should also be compared to the DSM-IV concepts of fully psychotic disorders that have not been present for long enough to meet the criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. These DSM-IV concepts are psychotic disorders not otherwise specified, brief psychotic disorders, and schizophreniform disorders. Yung et al. in 1996 gave the criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia and divided it as three main categories.[18]

These DSM-IV concepts are psychotic disorders not otherwise specified, brief psychotic disorders, and schizophreniform disorders. Yung et al. in 1996 gave the criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia and divided it as three main categories.[18]

Category 1, the patient should have at least one of the following attenuated (i.e., subthreshold) positive symptoms: ideas of reference, odd beliefs, or magical thinking; perceptual disturbance; odd thinking and speech; paranoid ideation; and odd behavior or appearance.

Category 2 consists of participants who have experienced transient psychotic symptoms, which have spontaneously resolved within a week.

Category 3 is a combination of genetic risk (i.e., being the first-degree relative of an individual with a diagnosis of schizophrenia) with changes in functioning. The patient must have undergone a substantial decline in the previous year. The criteria in the first two categories have been largely derived from positive symptoms, and that negative signs and symptoms were not utilized as the basis of any of the categories. [6,7]

[6,7]

The recent resurgent interest in the field of prodromal research has led to the development of various assessment tools. These tools can identify symptoms in the phase which calls for intervention. The various tools include:

Instrument for the retrospective assessment of onset of schizophrenia developed by Hafner et al. 1992

Bonn Scale for the assessment of basic symptoms by Huber et al. 1980

Structured Interview for Prodromal Symptoms (SIPS) by McGlashan 1996[8]

Scale for prodromal symptoms (SOPS) also by McGlashan 1996[8]

Multidimensional assessment of psychotic prodrome by Yung and McGory in 1996[6,7]

Comprehensive assessment of ARMS (CAARMS) by McGory et al. 2003.

Structured interviewing technique was followed in all these scales. The SIPS and SOPS to rate the prodromal symptoms were developed by research team from Yale University called The Prevention through Risk Identification, Management, and Education. Among these, the most widely used measure is the SIPS. It enhances positive predictive power, thus increasing the true-positives.[19] The SIPS is a diagnostic interview used to diagnose the prodromal syndromes and similar to the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV. The CAARMS defined the at-risk criteria and included in it the vulnerable groups, attenuated positive symptom groups, and the brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms.[20] The other symptoms and syndromes which are measured in these scales include genetic risks and deterioration, brief-limited psychotic symptoms, and attenuated positive symptoms; brief limited psychotic symptoms includes transient psychotic symptoms at a specified frequency over a given period. Unusual perceptual experiences and ideations that do not meet the level of conviction and severity required for hallucinations and delusions are characterized as attenuated positive symptoms. These are vital in UHR criteria and charted by all of these measures.

Among these, the most widely used measure is the SIPS. It enhances positive predictive power, thus increasing the true-positives.[19] The SIPS is a diagnostic interview used to diagnose the prodromal syndromes and similar to the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV. The CAARMS defined the at-risk criteria and included in it the vulnerable groups, attenuated positive symptom groups, and the brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms.[20] The other symptoms and syndromes which are measured in these scales include genetic risks and deterioration, brief-limited psychotic symptoms, and attenuated positive symptoms; brief limited psychotic symptoms includes transient psychotic symptoms at a specified frequency over a given period. Unusual perceptual experiences and ideations that do not meet the level of conviction and severity required for hallucinations and delusions are characterized as attenuated positive symptoms. These are vital in UHR criteria and charted by all of these measures.

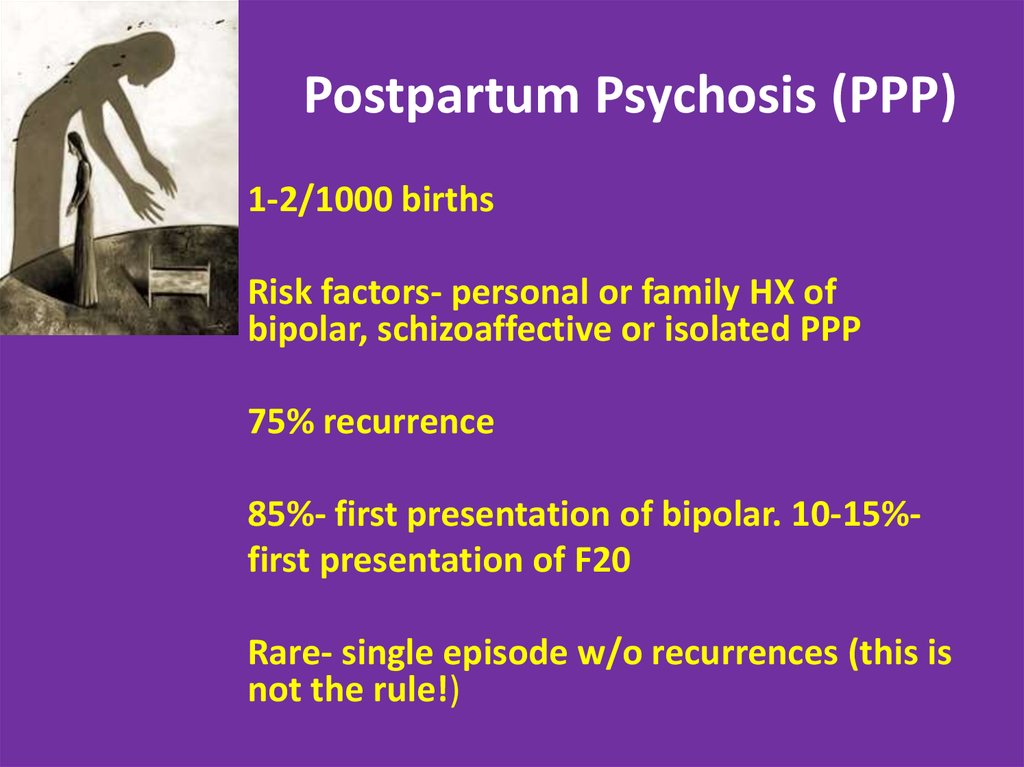

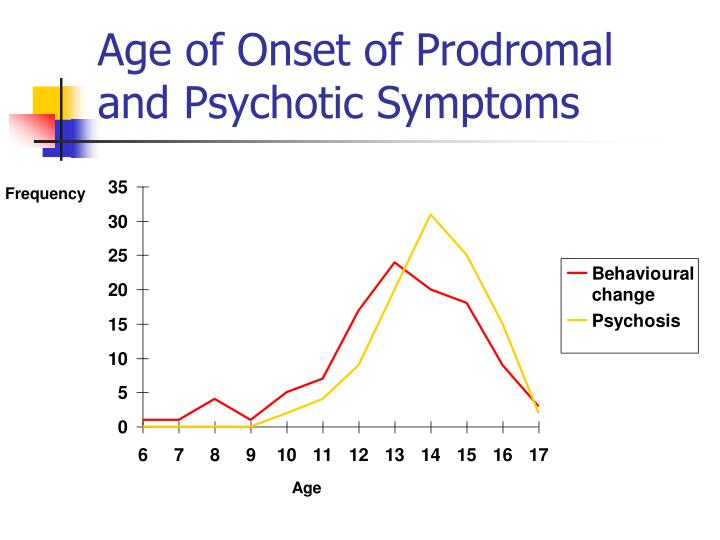

It was reported that 75% of the patients with schizophrenia passed through the stages of prodromal symptoms. Subthreshold psychotic symptoms were reported 1 year preceding the onset and nonspecific anxiety and affective symptoms much before this.[21,22] Only a proportion goes on to develop psychotic disorder. Current estimates suggest that 1 in 4 of the patients who can be categorized as high risk will convert to schizophrenia and hence warrant intervention. According to different studies, only 20%–40% of those who meet UHR criteria convert to psychosis within 2–4 years. Studies conducted in both Australia and the United States showed that young people with “subthreshold” psychotic symptoms and some evidence of functional decline with a history of genetic risk for schizophrenia were ascertained and followed longitudinally for the development of psychosis.[21,22,23] In a few earlier studies, it was seen that prodromal status was associated with a 40%–50% rate of conversion to psychosis in 1–2 years. A more modest rate of transition was explained by a group of researchers in North America. In Australia, 1-year transition rates for patients have steadily decreased over time 50% in 1995, 32% in 1997, 21% in 1992, and 12% in 2000.[23]

A more modest rate of transition was explained by a group of researchers in North America. In Australia, 1-year transition rates for patients have steadily decreased over time 50% in 1995, 32% in 1997, 21% in 1992, and 12% in 2000.[23]

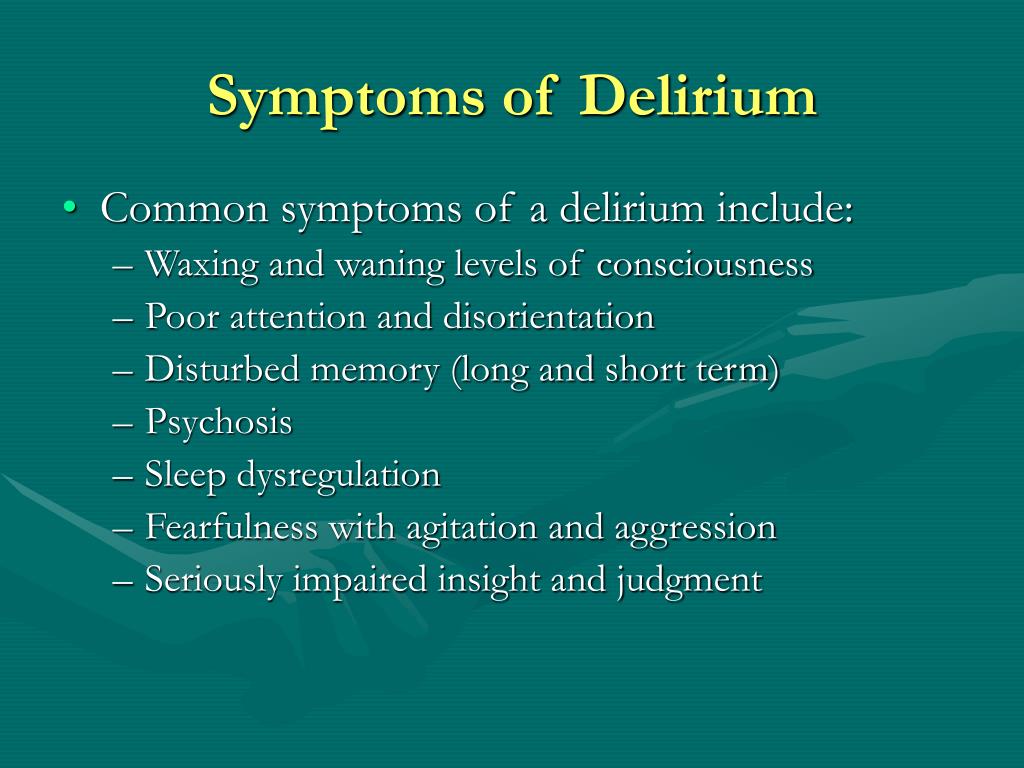

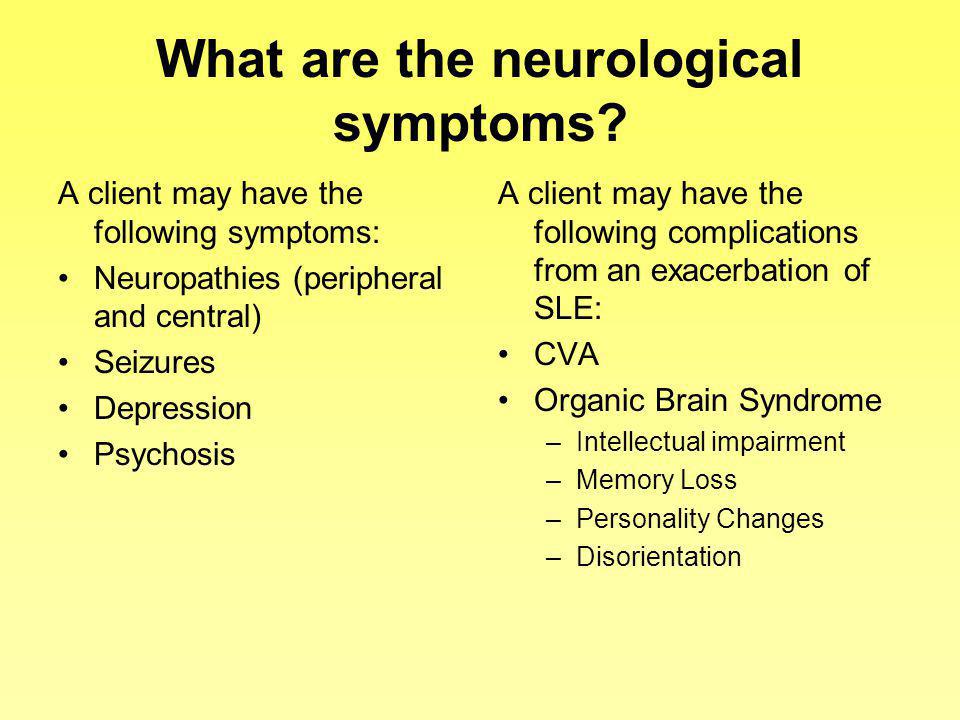

Cognitive deficits including memory, attention, and concentration are the most commonly documented clinical findings. This may incorporate relative disturbance in speed and verbal memory, social reasoning, and emotional processing. Various mood changes such as anxiety, depression, mood swings, sleep disturbances, irritability, anger, and suicidal ideas are reported as part of prodromal symptoms. Patient may also present with spectrum of conditions including obsessive-compulsive phenomenon and dissociative disorders. Even subtle changes such as social withdrawal, school refusal, deterioration in school work may be considered as part of prodrome and may require intervention if the person is under UHR category.

Much of the work on imaging and biomarkers was done by Pantelis et al. in 2003. Their studies focused on structural changes in the gray matter and following up these individuals at a later phase after they developed psychosis. The structures affected include right medial temporal, lateral temporal bilateral cingulated cortex, and inferior frontal cortex. On rescanning the individuals who developed psychosis, there was a reduction in gray matter in the left parahippocampal, fusiform, orbitofrontal, and cerebellar cortices whereas longitudinal changes were restricted to only cerebellum in those who did not become psychotic. This progressive change which was studied in adolescence was considered to be due to a combination of several factors. Genetic factors like those resulting from altered expression of genes are critical for neurodevelopmental processes such as glutaminergic N-methyl- D-aspartate α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid-receptor expression or altered dynamics of dopaminergic or GABAergic neurotransmitter systems.[24] Hormonal changes such as reproductive steroids could modulate brain maturational processes such as synaptic pruning or myelination.

in 2003. Their studies focused on structural changes in the gray matter and following up these individuals at a later phase after they developed psychosis. The structures affected include right medial temporal, lateral temporal bilateral cingulated cortex, and inferior frontal cortex. On rescanning the individuals who developed psychosis, there was a reduction in gray matter in the left parahippocampal, fusiform, orbitofrontal, and cerebellar cortices whereas longitudinal changes were restricted to only cerebellum in those who did not become psychotic. This progressive change which was studied in adolescence was considered to be due to a combination of several factors. Genetic factors like those resulting from altered expression of genes are critical for neurodevelopmental processes such as glutaminergic N-methyl- D-aspartate α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid-receptor expression or altered dynamics of dopaminergic or GABAergic neurotransmitter systems.[24] Hormonal changes such as reproductive steroids could modulate brain maturational processes such as synaptic pruning or myelination. Psychosocial and environmental factors also have a role in dendritic arborization. Biomarkers which have a role in early identification of psychosis have also been evaluated in studies by Schoebel et al. in 2009. Different categories of biomarkers representing inflammation, oxidative stress, endocannabinoids, glucocorticoids, and biogenic amine systems are dysregulated and interact with each other in the early phase of schizophrenia. Biomarkers for impending psychosis might identify high-risk individuals and thus help in halting the progression of aberrant neurodevelopmental processes.[25] This was also studied in researches in mouse models of maternal immune activation which revealed that interventions directed at maternal inflammatory cytokines protected against neurodevelopmental abnormalities in the offspring.[26] Targeting risk genes and environmental factors in the signaling pathway are found to restore functionality in a more efficacious way in these individuals. Studies have also indicated that treatments which reduce molecular deficits produced by genetic variants like folate supplementation in people with certain risk alleles have actually caused a decline in relapse rates.

Psychosocial and environmental factors also have a role in dendritic arborization. Biomarkers which have a role in early identification of psychosis have also been evaluated in studies by Schoebel et al. in 2009. Different categories of biomarkers representing inflammation, oxidative stress, endocannabinoids, glucocorticoids, and biogenic amine systems are dysregulated and interact with each other in the early phase of schizophrenia. Biomarkers for impending psychosis might identify high-risk individuals and thus help in halting the progression of aberrant neurodevelopmental processes.[25] This was also studied in researches in mouse models of maternal immune activation which revealed that interventions directed at maternal inflammatory cytokines protected against neurodevelopmental abnormalities in the offspring.[26] Targeting risk genes and environmental factors in the signaling pathway are found to restore functionality in a more efficacious way in these individuals. Studies have also indicated that treatments which reduce molecular deficits produced by genetic variants like folate supplementation in people with certain risk alleles have actually caused a decline in relapse rates. [27] Drugs which act on Val 158 and decreases catechol-o-methyl transferase activity when given at an early stage have improved the socio-occupational functioning in affected individuals.[28]

[27] Drugs which act on Val 158 and decreases catechol-o-methyl transferase activity when given at an early stage have improved the socio-occupational functioning in affected individuals.[28]

The importance of early detection focuses on prevention of the psychological and social disruption which results from psychosis. Minimizing the delay between the onset of psychosis and treatment is the primary objective for this diagnosis. Medications that decrease the stress levels have been found to reduce clinical deterioration in individuals with biological susceptibility for schizophrenia. Anti depressants, anxiolytics and mood stabilizers might in some cases enhance At Risk individual's ability to tide over stressful situations.[29] Studies have shown that combination of low dose Risperidone together with cognitive behavior therapy or supportive psychotherapy have shown a conversion rate of 9.7% (3/31) over 6 months in the experimental group compared to 35.7% (10/28) in the control group. Over a 12 month follow up period it was seen that 20 subjects became psychotic. Therefore, the 12 month transition rate was 40.8% (20/49). Similar placebo controlled and double blind trial of olanzapine focusing on symptoms over 8 weeks, also showed improvement in prodromal patients primarily limited to the SOPS and PANSS scales. In this study it was seen that there was a higher transition rate in the group where olanzapine was discontinued.[30] 15 patients were observed over 8 weeks in an open label study administering Aripiprazole. Significant improvement was seen in symptomatology in these patients.[31] The prevalence of sub-threshold psychosis was higher in subjects at genetic risk.[32] Antipsychotic medications for such people seem to be a logical extension for treatment protocol as a whole.[33,34,35] In a double blind, randomized, placebo controlled treatment study; patients were supplemented with omega 3 fatty acids. They carried out the trial on 81 ultra high risk individuals. The experimental group was given 1.

Over a 12 month follow up period it was seen that 20 subjects became psychotic. Therefore, the 12 month transition rate was 40.8% (20/49). Similar placebo controlled and double blind trial of olanzapine focusing on symptoms over 8 weeks, also showed improvement in prodromal patients primarily limited to the SOPS and PANSS scales. In this study it was seen that there was a higher transition rate in the group where olanzapine was discontinued.[30] 15 patients were observed over 8 weeks in an open label study administering Aripiprazole. Significant improvement was seen in symptomatology in these patients.[31] The prevalence of sub-threshold psychosis was higher in subjects at genetic risk.[32] Antipsychotic medications for such people seem to be a logical extension for treatment protocol as a whole.[33,34,35] In a double blind, randomized, placebo controlled treatment study; patients were supplemented with omega 3 fatty acids. They carried out the trial on 81 ultra high risk individuals. The experimental group was given 1. 2g/day omega 3 fatty acids. It was observed that after 40 weeks monitoring period 2 of the 41 in the experimental group and 11 of the 40 in the placebo group had converted to psychosis. The patients materialized improvement in positive, negative and general symptoms with betterment in functioning in comparison to the placebo group.[36] Besides pharmacological interventions, study of the effect of psychosocial modification on the vulnerable individuals helps the young person to regain their capacity for psychological well-being and improved quality of life. Psycho education assists the young person and their family in understanding psychosis as a brain disorder rather than a mental illness. Individuals should be taught about the coping and problem solving skills to better help the people deal with the manifestations of the illness.

2g/day omega 3 fatty acids. It was observed that after 40 weeks monitoring period 2 of the 41 in the experimental group and 11 of the 40 in the placebo group had converted to psychosis. The patients materialized improvement in positive, negative and general symptoms with betterment in functioning in comparison to the placebo group.[36] Besides pharmacological interventions, study of the effect of psychosocial modification on the vulnerable individuals helps the young person to regain their capacity for psychological well-being and improved quality of life. Psycho education assists the young person and their family in understanding psychosis as a brain disorder rather than a mental illness. Individuals should be taught about the coping and problem solving skills to better help the people deal with the manifestations of the illness.

It is mandatory on clinicians to exercise caution before labeling a person for early intervention. The symptoms of prodrome are subtle and often missed by family members and primary care physicians. Hence, it is important to observe the patient at frequent intervals and monitor the progress over the course of time. It is equally important to communicate the concept of prodrome to the primary care physicians and primary health-care staff so that early recognition and referral is done, as they are the point of first contact for the individual. Even at this low threshold sufficient referral guidelines must be present for faster, better, and appropriate care. Promotion of mental health services is essential for people to understand about possible stress-coping strategies which can also act as a prophylaxis against impending psychosis.[33]

Hence, it is important to observe the patient at frequent intervals and monitor the progress over the course of time. It is equally important to communicate the concept of prodrome to the primary care physicians and primary health-care staff so that early recognition and referral is done, as they are the point of first contact for the individual. Even at this low threshold sufficient referral guidelines must be present for faster, better, and appropriate care. Promotion of mental health services is essential for people to understand about possible stress-coping strategies which can also act as a prophylaxis against impending psychosis.[33]

A danger is undoubtedly exists that early conclusions may lead to widespread use of antipsychotic medications as standard care in the treatment of symptoms which appear prodromal. The extent to which an intervention will work is actually difficult to assess. Naturalistic studies establishing the base rates of eventual illness are, therefore, critical for evaluating the successfulness of early treatment. The research community of all times have put forth significant amount of data to identify and predict vulnerability of individuals who might develop psychosis. The critical period of intervention if identifiable clarifies the doubts about faster and better outcomes. Time should be spent to explore the ethical and social implications at this stage, and the juncture gives us a moment to consider what measures might be taken to minimize liabilities but does not preclude the opportunity for patient to receive treatment and improve the quality of living. Of course, much discretion should be warranted in introducing the idea that an individual may be at risk in developing psychosis. However, quintessential diagnosis is facilitated by exposure to all the risks involved together with accurate information about the array of therapies that may have a significant impact in the course of schizophrenia.

The research community of all times have put forth significant amount of data to identify and predict vulnerability of individuals who might develop psychosis. The critical period of intervention if identifiable clarifies the doubts about faster and better outcomes. Time should be spent to explore the ethical and social implications at this stage, and the juncture gives us a moment to consider what measures might be taken to minimize liabilities but does not preclude the opportunity for patient to receive treatment and improve the quality of living. Of course, much discretion should be warranted in introducing the idea that an individual may be at risk in developing psychosis. However, quintessential diagnosis is facilitated by exposure to all the risks involved together with accurate information about the array of therapies that may have a significant impact in the course of schizophrenia.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

1. Jablensky A. The diagnostic concept of schizophrenia: its history, evolution, and future prospects. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12:271–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Häfner H. The Concept of Schizophrenia: From Unity to Diversity. Advances in Psychiatry 2014. 2014:1–39. [Google Scholar]

3. Bruijnzeel D, Tandon R. The Concept of Schizophrenia: From the 1850s to the DSM 5. Psychiatric Annals. 2011;41:289–95. [Google Scholar]

4. Tassman A, Kay J, Liebermann AJ, Michael B, Michelle B. The Neurobiology of Schizophrenia. Wiley; 2011. Psychiatry; pp. 302–7. [Google Scholar]

5. Barbara A, Lenz T, Christopher W. Schizophrenia Prodrome Revisited: A Neurodevelopmental Perspective. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003:29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, McGorry PD. Prediction of psychosis: a step towards indicated prevention of schizophrenia. British Journal o Psychiatry. 1998;172(suppl 33):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention of schizophrenia: research. Schizophr. Bull. 1996;22:327–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention of schizophrenia: research. Schizophr. Bull. 1996;22:327–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JMJ, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, and Szymanski SR. Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:1183–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Beiser M, Erickson D, Fleming JAE, Iacono WG. Establishing the onset of psychotic illness. American journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1349–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Fu EJ, Cadenhead KS. Progress in the prospective study of schizophrenia prodrome. Current Psychosis and therapeutics Reports. 2005;3:69–175. [Google Scholar]

11. Clinical Practice Guidelines. Treatment of Schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50:43–4. [Google Scholar]

12. Joa A, Jens G, Bronnick K, McGlashan T, Johanssen O. Primary prevention of psychosis through interventions in the symptomatic prodromal phase, a pragmatic Norwegian Ultra High Risk Study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Shrivastava A. Prodromal Research: Public Health intiative for prevention of Schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:13–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Haahr U, Friis S, Larsen TK, Melle I, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S, et al. First-episode psychosis: Diagnostic stability over one and two years. Psychopathology. 2008;41:322–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Harkavy-Friedman JM. Can early detection of psychosis prevent suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:768–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Keshavan MS, Shrivastava A, Gangadhar BN. Early intervention in psychiatric disorders: Challenges and relevance in Indian context. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S 153–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. 4th ed. Washington, DC: The Association; 1994. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

18. Yung A, McGorry P. The Prodromal Phase of First-episode Psychosis: Past and Current Conceptualizations. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1996;22:353–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yung A, McGorry P. The Prodromal Phase of First-episode Psychosis: Past and Current Conceptualizations. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1996;22:353–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Goulding S, Holtzmann C, Trotmann H, Ryan A. Prodrome and clinical risk for psychotic disorders. Child and adolescent Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2013;22:557–567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Kaur T, cadenhead K. Treatment Implications of THE Schizophrenia Prodrome. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010;4:97–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Sorensen HJ, Mortensen EL, Reinisch JM, et al. Parental psychiatric hospitalisation and offspring schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10:571–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Hafner H, Maurer K, Loffler W, Heiden W, Hambrect M, Lutter F. Modeling the Early Curse of Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2003;29:325–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Cheryl B, Barbara C, Michael B. The Psychosis Risk Syndrome and its Proposed Inclusion in The DSM V. A Risk benefit analysis. PsyClin of North America. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;120:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A Risk benefit analysis. PsyClin of North America. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;120:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, Wood SI, Suckling I, Phillips LJ, et al. Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: A cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI comparison. Lancet. 2003;361:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Goff CD, Romero K, Paul J, Rodriguez MP, Crandall D, Potkin S. Biomarkers for drug development in early psychosis: Current issues and promising directions. Journal of European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;26:923–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Ito HT, Smith SE, Hsiao E, Patterson PH. Maternal immune activation alters nonspatial information processing in the hippocampus of the adult offspring. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:930–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Roffman JL, Lamberti Achytes E, Macklin EA, Galendez GC. Randomized Multicenter Investigation of Folate Plus Vitamin B12 Supplementation in Schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:481–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:481–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Apud JA, Mattay V, Chen J, Kolachana BS, Callicott J H, Egan Tolcapone improves cognition and cortical information processing in normal human subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1011–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Cornblatt B, Obuchowski M, Ditkowsky K, Singer A, Malhotra A, Becker J, et al. The hillside RAPP clinic: a research/early intervention center for the schizophrenia prodrome. Schizophr Res. 1999;36:6. [Google Scholar]

30. Kulhara P, Banerjee A, Dutt A. Early intervention in Schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:128–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Woods SW, Miller TJ, Davidson L, Hawkins KA, Semyak MJ, McGlashan TH. Estimated yield of early detection of prodromal or first episode patients by screening first degree relatives of schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;52:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Razali SM, Abidin ZZ, Othman Z, Yassin MA. Screening for schizophrenia in intial prodromal phase: Detecting the sub-threshold psychosis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;16:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Screening for schizophrenia in intial prodromal phase: Detecting the sub-threshold psychosis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;16:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Kulhara P, Banerjee A, Dutt A. Early intervention in Schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:128–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Shrivastava A, Mc Gory PD, Tsuang M, et al. Attenuated Psychotic Symptoms Syndrome as a risk of psychosis, diagnosis in DSM-V: the debate. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:57–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Grover S, Chakrabarthi S, Kulhara P, Avasthi A. Clinical practice Guidelines for management of schizophrenia. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2017;59:19–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Amminger GP, McGorry PD. Update on Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Early-Stage Psychotic Disorders? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:309–310. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Early signs, diagnosis and therapeutics of the prodromal phase of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

1. Bleuler E. In: Dementia Praecox of the Group of Schizophrenias. Zinkin J, editor. NY, USA: International Universities Press; 1950. (1911) (Translator) [Google Scholar]

Bleuler E. In: Dementia Praecox of the Group of Schizophrenias. Zinkin J, editor. NY, USA: International Universities Press; 1950. (1911) (Translator) [Google Scholar]

2. Kraepelin E, Barclay R, Robertson GM. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Edinburgh, UK: E & S Livingstone; 1919. [Google Scholar]

3. Hughlings-Jackson J. Intellectual warnings of epileptic seizures. In: Taylor J, editor. Selected Writings of John Hughlings-Jackson. London, UK: Hodder and Stoughton; 1931. pp. 274–275. [Google Scholar]

4. Strauss J, Carpenter W. The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: II. Relationships between predictors and outcome variables. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1974;31:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Andreasen N, Olsen S. Negative v positive schizophrenia: definition and validation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1982;39:789–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Andreasen N, Grove W. Evaluation of positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Psychobiol. 1986;1:108–121. [Google Scholar]

1986;1:108–121. [Google Scholar]

7. Schneider K. In: Clinical Psychopathology. Hamilton MW, editor. NY, USA: Grune and Stratton Inc; 1959. (Translator) [Google Scholar]

8. Carpenter WT, Strauss JS, Muleh S. Are there pathognomonic symptoms in schizophrenia: an empiric investigation of Schneider’s first-rank symptom. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1973;28:847–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Liddle P. The symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: a re-examination of the positive–negative dichotomy. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1987;151:145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2004;72:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ. Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:315–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Meltzer HY, Thompson PA, Lee MA, Ranjan R. Neuropsychologic deficits in schizophrenia: relation to social function and effect of antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:S27–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuropsychologic deficits in schizophrenia: relation to social function and effect of antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:S27–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the ‘right stuff?’ Schizophr. Bull. 2000;26:119–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. McGurk SR, Meltzer HY. The role of cognition in vocational functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2000;45:175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Leeson VC, Barnes TRE, Hutton SB, Ron MA, Joyce EM. IQ as a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal, four-year study of first-episode psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2009;107:55–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Gold JM, Hahn B, Strauss GP, Waltz JA. Turning it upside down: areas of preserved cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2009;19:294–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Malla A, Payne J. First-episode psychosis: psychopathology, quality of life, and functional outcome. Schizophr. Bull. 2005;31:650–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Malla A, Payne J. First-episode psychosis: psychopathology, quality of life, and functional outcome. Schizophr. Bull. 2005;31:650–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Brewer WJ, Wood SJ, Phillips LJ, et al. Generalized and specific cognitive performance in clinical high-risk cohorts: a review highlighting potential vulnerability markers for psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 2006;32:538–555. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Murray RM, Lewis SW. Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder? Br. Med. J. 1987;295:681–682. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Davidson M, Reichenberg A, Rabinowitz J, Weiser M, Kaplan Z, Mark M. Behavioural and intellectual markers for schizophrenia in apparently healthy male adolescents. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:1328–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Munro JC, Russell AJ, Murray RM, Kerwin RW, Jones PB. IQ in childhood psychiatric attendees predicts outcome of later schizophrenia at 21 year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2002;106:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scand. 2002;106:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Schenkel LS, Silverstein SM. Dimensions of premorbid functioning in schizophrenia: a review of neuromotor, cognitive, social, and behavioral domains. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2004;130:241–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Walker E. Developmentally moderated expressions of the neuropathology of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1994;20:453–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Walker E, Lewis N, Loewy R, Palyo S. Motor dysfunction and risk for schizophrenia. Dev. Psychopathol. 1999;11:509–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Zipursky R, Christensen B, Mikulis D. Stable deficits in gray matter volumes following a first episode of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2004;71:515–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode outcome patients: a systematic review. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:1785–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Barnes TRE, Leeson VC, Mutsatsa SH, Watt HC, Hutton SB, Joyce EM. Duration of untreated psychosis and social function: 1-year follow-up study of first-episode schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2008;193:203–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Addington J, Van Mastrigt S, Addington D. Duration of untreated psychosis: impact on 2-year outcome. Psychol. Med. 2004;34:277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Harrington SM, McGorry PD, Krstev H. Does treatment delay in first-episode psychosis really matter? Psychol. Med. 2003;33:97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Shenton M, Dickey C, Frumin M, McCarley R. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2001;49:1–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr. Res. 2001;49:1–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Vita A, De Peri L, Silenzi C, Dieci M. Brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging studies. Schizophr. Res. 2006;82:75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Wright I, Rabe-Hesketh S, Woodruff P, David A, Murray R, Bullmore E. Meta-analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:16–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Lappin J, Morgan K, Morgan C, et al. Gray matter abnormalities associated with duration of untreated psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2006;83:145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, et al. Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI comparison. Lancet. 2003;361:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Lieberman JA, Malaspina D, Jarskog LF. Preventing clinical deterioration in the course of schizophrenia: the potential for neuroprotection. Prim. Psychiatry. 2006;13:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prim. Psychiatry. 2006;13:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. McGlashan TH, Miller TJ, Woods SW. Pre-onset detection and intervention research in schizophrenia psychoses: current estimates of benefit and risk. Schizophr. Bull. 2001;27:563–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Phillips LJ, McGorry P, Yung AR, McGlashan TH, Cornblatt B, Klosterkotter J. Prepsychotic phase of schizophrenia and related disorders: recent progress and future opportunities. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;187:33–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, Cornell CU, Auther AM, Nakayama E. The schizophrenia prodrome revisited: a neurodevelopmental perspective. Schizophr. Bull. 2003;29:633–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J, Maier W, Klosterkotter J. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36:182–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. an der Heiden W, Hafner H. The epidemiology of onset and course of schizophrenia. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000;250:292–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The epidemiology of onset and course of schizophrenia. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000;250:292–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Rosen JL, Miller TJ, D’Andrea JT, McGlashan TH, Woods SW. Comorbid diagnoses in patients meeting criteria for the schizophrenia prodrome. Schizophr. Res. 2006;85:124–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Gross G, Huber G, Klosterkotter J, Linz M. BSABS: Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

44. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The initial prodrome in psychosis: descriptive and qualitative aspects. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 1996;30:587–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkotter J. Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms – prediction list, BSABS-P. Cologne, Germany: University of Cologne; 2002. [Google Scholar]

46. Klosterkotter J, Hellmich M, Steinmeyer EM, Schultze-Lutter F. Diagnosing schizophrenia in the initial prodromal phase. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry. 2001;58:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Siever LJ, Davis KL. The pathophysiology of schizophrenia disorders: perspectives from the spectrum. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:398–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Olsen KA, Rosenbaum B. Prospective investigations of the prodromal state of schizophrenia: review of studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006;113:247–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell’Olio M. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 2005;39:964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr. Bull. 1996;22:353–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ. Ethics and early intervention in psychosis: keeping up the pace and staying in step. Schizophr. Res. 2001;51:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. de Koning MB, Bloemen OJN, van Amelsvoort TAMJ, et al. Early intervention in patients at ultra high risk of psychosis: benefits and risks. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009;119:426–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

de Koning MB, Bloemen OJN, van Amelsvoort TAMJ, et al. Early intervention in patients at ultra high risk of psychosis: benefits and risks. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009;119:426–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Cadenhead K. Vulnerability markers in the schizophrenia spectrum: implications for phenomenology, genetics, and the identification of the schizophrenia prodrome. Psychiatry Clin. N. Am. 2002;25:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Mason O, Startup M, Halpin S, Schall U, Conrad A, Carr V. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with “at-risk mental states” Schizophr. Res. 2004;71:227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins DO, et al. The PRIME North American randomized double-blind clinical trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients at risk of being prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. I. Study rationale and design. Schizophr. Res. 2003;61:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead DO, Ventura J, McFarlane CA. Prodromal assessment with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr. Bull. 2003;29:703–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prodromal assessment with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr. Bull. 2003;29:703–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Morrison AP, French P, Walford L, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;185:291–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] •• Seminal article on the first well-designed psychological intervention in ultra-high-risk (UHR) participants.

58. Nieman DH, Rike WH, Becker HE, et al. Prescription of antipsychotic medication to patients at ultra high risk of developing psychosis. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr. Res. 2004;67:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr. Res. 2004;67:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Bak M, Delespaul P, Hanssen M, de Graaf R, Vollebergh W, van Os J. How false are “false” positive psychotic symptoms? Schizophr. Res. 2003;62:187–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Yung AR, Yuen HP, Berger G, et al. Declining transition rate in ultra high risk (prodromal) services: dilution or reduction of risk? Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:673–681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Green MF. What are the functional consequences of the neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am. J. Psychiatry. 1996;153:321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Harvey PD, Howanitz E, Parrella M, et al. Symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills in geriatric patients with lifelong schizophrenia: a comparison across treatment sites. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1998;155:1080–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Harvey PD, Silverman JM, Mohs RC, et al. Cognitive decline in late-life schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of geriatric chronically hospitalized patients. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;45:32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Jahshan C, Heaton RK, Golshan S, Cadenhead KS. Course of neurocognitive deficits in the prodrome and first episode of schizophrenia. Neuropsychology. 2010;24:109–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Bersani G, Orlandi V, Kotzalidis GD, Pancheri P. Cannabis and schizophrenia: impact on onset, course, psychopathology and outcomes. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2002;252:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Boydell J, Dean K, Dutta R, Giouroukou E, Fearon P, Murray R. A comparison of symptoms and family history in schizophrenia with and without prior cannabis use: implications for the concept of cannabis psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2007;93:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Hambrecht M, Hafner H. Cannabis, vulnerability, and the onset of schizophrenia: an epidemiological perspective. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 2000;34:468–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] • Clearly delineates various pathways of potential effects of cannabis on the course of schizophrenia.

Cannabis, vulnerability, and the onset of schizophrenia: an epidemiological perspective. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 2000;34:468–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] • Clearly delineates various pathways of potential effects of cannabis on the course of schizophrenia.

70. Cassano GB, Pini S, Saettoni M, Rucci P, Dell’Osso L. Occurrence and clinical correlates of psychiatric comorbididty in patients with psychotic disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59:60–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Stefanis NC, Delespaul P, Henquet C, Bakoula C, Stefanis CN, Van Os J. Early adolescent cannabis exposure and positive and negative dimensions of psychosis. Addiction. 2004;99:1333–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Compton MT, Weiss PS, West JC, Kaslow NJ. The associations between substance use disorders, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, and Axis IV psychosocial problems. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2005;40:939–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Drake RE, Wallach MA. Substance abuse among the chronic mentally ill. Hosp. Community Psychiatry. 1989;40:1041–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hosp. Community Psychiatry. 1989;40:1041–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. D’Souza DC, Abi-Saab WM, Madonick S, Forselius-Bielen K, Doersch A, Braley G. δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol effects in schizophrenia: implications for cognition, psychosis, and addiction. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:594–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Kavanagh DJ. Management of co-occuring substance use disorders. In: Mueser KT, Jeste DV, editors. Clinical Handbook of Schizophrenia. NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 459–470. [Google Scholar]

76. Compton MT, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cannabis use, first-episode psychosis, and schizotypy: a summary and synthesis of recent literature. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2007;3:161–171. [Google Scholar]

77. Arseneault LM, Cannon M, Witton J, Murray M. Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;184:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] • Rigorous review of prospective studies addressing the potential causal association between cannabis use and risk of developing psychosis.

78. Phillips LJ, Curry C, Yung AR, Yuen HP, Adlard S, McGorry PD. Cannabis use is not associated with development of psychosis in an ‘ultra’ high-risk group. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 2002;36:800–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Kristensen K, Cadenhead KS. Cannabis abuse and risk for psychosis in a prodromal sample. Psychiatry Res. 2007;151:151–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Cannon T. Neurodevelopment and the transition from schizophrenia prodrome to schizophrenia: research imperatives. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;64:737–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. McGorry PD, Nelson B, Amminger P, et al. Intervention in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a review and future directions. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2009;70:1206–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] • Succinct review of the influence of interventions tested in UHR individuals.

82. Goetz D, Goetz R, Yale S, et al. Comparing early and chronic psychosis clinical characteristics. Schizophr. Res. 2004;70:120. [Google Scholar]

Schizophr. Res. 2004;70:120. [Google Scholar]

83. Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, et al. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:361–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Keefe RSE, Silva SG, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA. The effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 1999;25:201–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Keefe RSE, Sweeney JA, Hongbin G, Hamer RM, Perkins DO, McEvoy JP. Effects of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone on neurocognitive function in early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:1061–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Tandon R, DeQuardo J, Taylor S, et al. Phasic and enduring negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Biological markers and relationship to outcome. Schizophr. Res. 2000;45:191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Meltzer HY, Thompson PA, Lee MA, Ranjan R. Neuropsychologic deficits in schizophrenia: relation to social function and effect of antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:S27–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuropsychologic deficits in schizophrenia: relation to social function and effect of antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:S27–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. McGurk SR, Meltzer HY. The role of cognition in vocational functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2000;45:175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] •• Seminal article on the first randomized, controlled pharmacological intervention in UHR participants.

90. Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, Yuen JP, et al. Medium term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra high risk of psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2007;96:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Cannon TD, van Erp TG, Rosso IM, et al. Fetal hypoxia and structural brain abnormalities in schizophrenic patients, their siblings, and controls. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fetal hypoxia and structural brain abnormalities in schizophrenic patients, their siblings, and controls. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Woods SW, Breier A, Zipursky RB, et al. Randomized trial of olanzapine versus placebo in the symptomatic acute treatment of the schizophrenic prodrome. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;54:453–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins DO. Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:790–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Woods SW, Tully EM, Walsh BC, Hawkins KA, Callahan JL, Cohen SJ. Aripiprazole in the treatment of the psychosis prodrome: an open-label pilot study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;191:S96–S101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Ruhrmann S, Bechdolf A, Kuhn K-U, Wagner M, Schultze-Lutter F, Janssen B. Acute effects of treatment for prodromal symptoms for people putatively in a late initial prodromal state of psychosis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;191:S88–S95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;191:S88–S95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Moncrieff J. Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006;114:3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, et al. Can antidepressants be used to treat the schizophrenia prodrome? Results of a prospective, naturalistic treatment study of adolescents. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68:546–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Fusor-Poli P, Valmaggia L, McGuire P. Can antidepressants prevent psychosis? Lancet. 2007;370:1746–1748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Walker EF, Cornblatt BA, Addington J, et al. The relation of antipsychotic and antidepressant medication with baseline symptoms and symptom progression: a naturalistic study of the North American Prodrome Longitudinal sample. Schizophr. Res. 2009;115:50–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Benton MK, Schroeder HE. Social skills training with schizophrenics: a meta-analytic evaluation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1990;58:741–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Benton MK, Schroeder HE. Social skills training with schizophrenics: a meta-analytic evaluation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1990;58:741–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Combs DR, Adams SD, Penn DL, Roberts D, Tiegreen J, Stern P. Social cognition and interaction traning (SCIT) for inpatients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: preliminary findings. Schizophr. Res. 2007;91:112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Pitschel-Walz G, Leucht S, Bauml J, Kissling W, Engel RR. The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia – a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2001;27:73–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, McHugo GJ, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:1791–1802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Gould RA, Mueser KT, Bolton E, Mays V, Goff D. Cognitive therapy for psychosis in schizophrenia: an effect size analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2001;48:3335–3342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Res. 2001;48:3335–3342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Gaudiano BA. Is symptomatic improvement in clinical trials of cognitive–behavioral therapy for psychosis clinically significant? J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2006;12:11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: II. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of social skills training and cognitive remediation. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:783–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Rathod S, Turkington D. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: a review. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2005;18:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Turkington D, Dudley R, Warman DM, Beck AT. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: a review. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2004;10:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Zimmerman G, Favrod J, Trieu VH, Pomini V. The effect of cognitive behavioral treatment on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2005;77:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr. Res. 2005;77:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Falloon IR. Early intervention for first episodes of schizophrenia: a preliminary exploration. Psychiatry. 1992;55:4–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Morrison AP, French P, Parker S, et al. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:682–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Bechdolf A, Wagner M, Veith V, et al. Randomized controlled multicentre trial of cognitive behavior therapy in the early intitial prodromal state: effects on social adjustment post treatment. Early Intervent. Psychiatry. 2007;1:71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Nordentoft M, Thorup A, Petersen L, et al. Transition rates from schizotypal disorder to psychotic disorder for first-contact patients included in the OPUS trail. A randomized clinical trial of integrated treatment and standard treatment. Schizophr. Res. 2006;83:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr. Res. 2006;83:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. Berger GE, Smesny S, Amminger GP. Bioactive lipids in schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2006;18:85–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Amminger GP, Berger GE, Schzfer MR, Klier C, Friedrich MH, Feucht M. Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation in children with autism: a double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;61:551–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Berger GE, Proffitt T-M, McConchie M, Yuen JP, Wood SJ, Amminger P. Ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68:1867–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Emsley R, Myburgh C, Oosthuizen P, van Rensburg SJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled study of ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid as supplemental treatment in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:1596–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Richardson AJ, Montgomery P. The Oxford–Durham study: a randomized, controlled trial of dietary supplementation with fatty acids in children with developmental coordination disorder. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1360–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics. 2005;115:1360–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Amminger GP, Schaefer MR, Papageorgiou K, et al. Omega 3 fatty acids reduce the risk of early transition to psychosis in ultra-high risk individuals: a double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled treatment study. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33 Suppl:418–419. [Google Scholar]

120. Amminger GP, Schaefer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Cotton SM, Harrigan SM. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychiatric disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67:146–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] •• Important study demonstrating significant outcomes of a low-risk, effective treatment for UHR individuals.

121. Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Kane JM. Treatment of the schizophrenia prodrome: is it presently ethical? Schizophr. Res. 2001;51:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. McGorry PD, Yung A, Phillips L. Ethics and early intervention in psychosis: keeping up the pace and staying in step. Schizophr. Res. 2001;51:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. McGlashan T. Psychosis treatment prior to psychosis onset: ethical issues. Schizophr. Res. 2001;51:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Haroun N, Dunn L, Haroun A, Cadenhead KS. Risk and protection in prodromal schizophrenia: ethical implications for clinical practice and future research. Schizophr. Bull. 2006;32:166–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention in psychosis: an ethical paradigm shift. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;187:S113–S115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Compton MR, Goulding SM, Ramsay CE, Addington J, Corcoran C, Walker EF. Early detection and intervention for psychosis: perspectives from North America. Clin. Neuropsychiatry. 2008;5:263–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Early interventions for people at risk of developing psychosis

Review question

Is there high quality evidence that interventions for people at risk of developing psychosis are effective?

Relevance

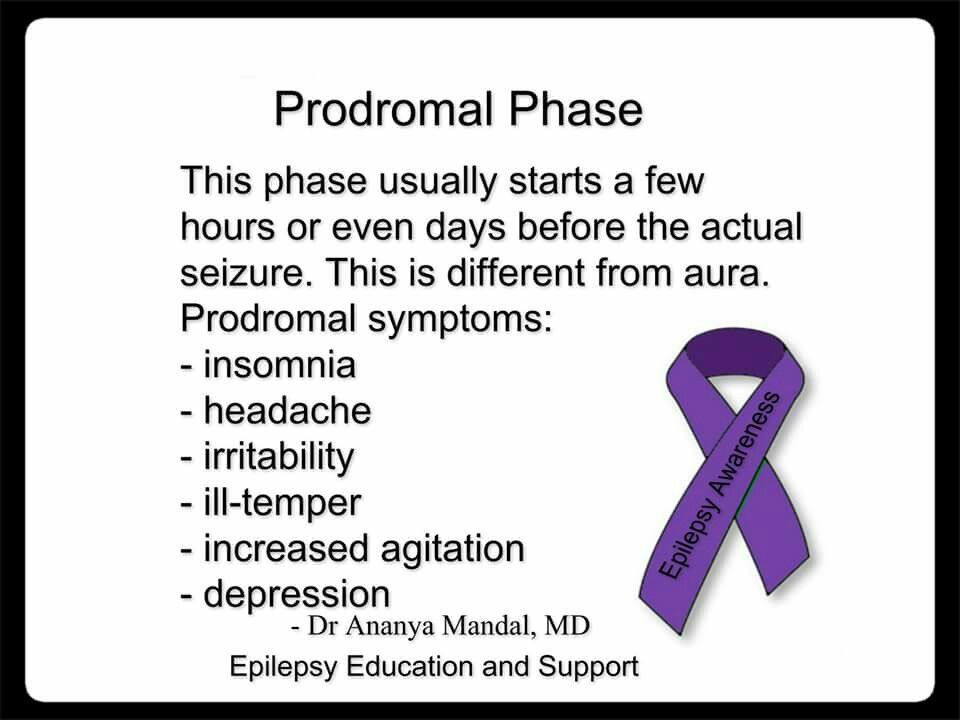

Psychoses are serious mental conditions characterized by a loss of contact with reality. The first overt episode of psychosis may be preceded by a "prodromal" period of at least six months in which the person experiences gradual, non-specific changes in thoughts, perceptions, behavior, and functioning. Although the person is experiencing changes, they have not yet begun to experience more obvious psychotic symptoms such as delusions (fixed false beliefs) or hallucinations (perceptions without a cause). A number of treatment approaches that combine pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and psychosocial treatment developed worldwide are currently focused on the prevention of psychosis in people at risk by providing prodromal treatment. This review assesses the available evidence on the impact of different treatment approaches in people who have not yet been diagnosed with non-affective psychosis but who are in the prodromal stage of psychosis.

The first overt episode of psychosis may be preceded by a "prodromal" period of at least six months in which the person experiences gradual, non-specific changes in thoughts, perceptions, behavior, and functioning. Although the person is experiencing changes, they have not yet begun to experience more obvious psychotic symptoms such as delusions (fixed false beliefs) or hallucinations (perceptions without a cause). A number of treatment approaches that combine pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and psychosocial treatment developed worldwide are currently focused on the prevention of psychosis in people at risk by providing prodromal treatment. This review assesses the available evidence on the impact of different treatment approaches in people who have not yet been diagnosed with non-affective psychosis but who are in the prodromal stage of psychosis.

Search for evidence

On June 8, 2016 and August 4, 2017, we electronically searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's specialized clinical trial registry to find clinical trials that randomly assigned people at risk of developing psychosis to receive various treatments to prevent the development of psychosis.

Discovered evidence

We were able to include 20 studies with 2151 participants. These studies have analyzed a wide range of treatments. All survey results are of poor quality at best. One small study suggests that people at risk for psychosis may benefit from taking omega-3 fatty acids in terms of reducing the rate of transition to psychosis. Other studies have found that the addition of antipsychotics to supportive care seems to make little difference in terms of progression to illness. When cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) + supportive care was compared with supportive care alone, about 8% of participants who were given a combination of CBT and supportive care progressed to psychosis within a follow-up period of up to 18 months, compared with twice the percentage of people who received only supportive care. This may be important, but this data is of very low quality. All other studies of CBT and other care approaches have found no clear differences between treatments for psychotic transition.

Terminals

Considerable effort and investment has been made in testing treatment approaches for the prevention of first episode schizophrenia. There is currently some low-quality evidence suggesting that omega-3 fatty acids may be effective, but there is no high-quality evidence that any type of treatment is effective, and firm conclusions cannot be drawn.

Translation notes:

Translation: Iskakova Alua Kanatovna. Editing: Dilyara Farkhadovna Nurkhametova. Russian translation project coordination: Cochrane Russia - Cochrane Russia, Cochrane Geographic Group Associated to Cochrane Nordic. For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: [email protected]

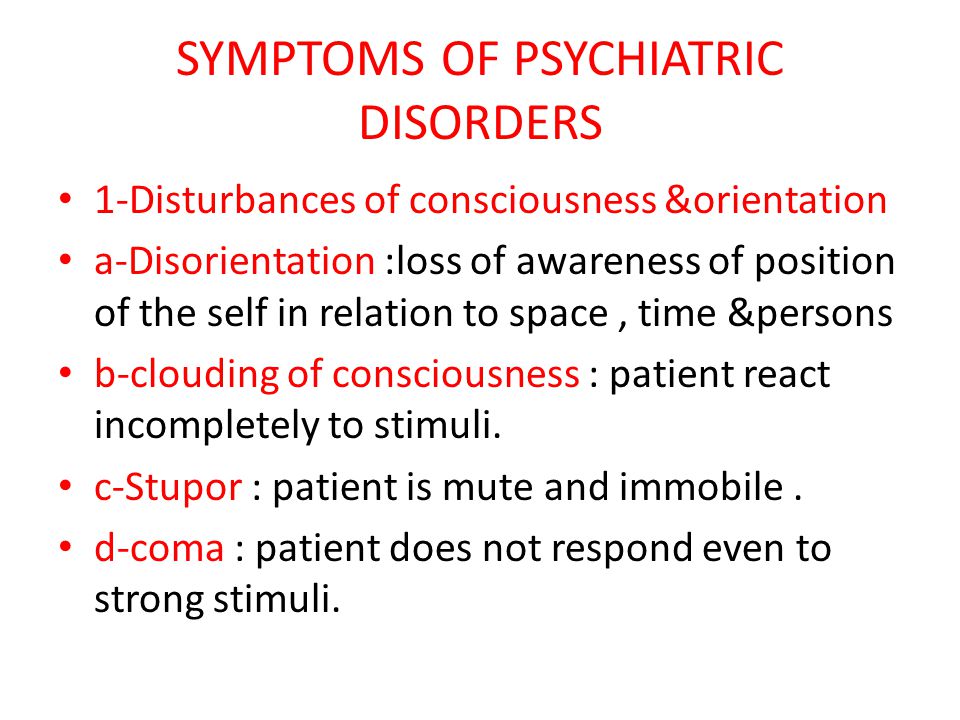

Symptoms

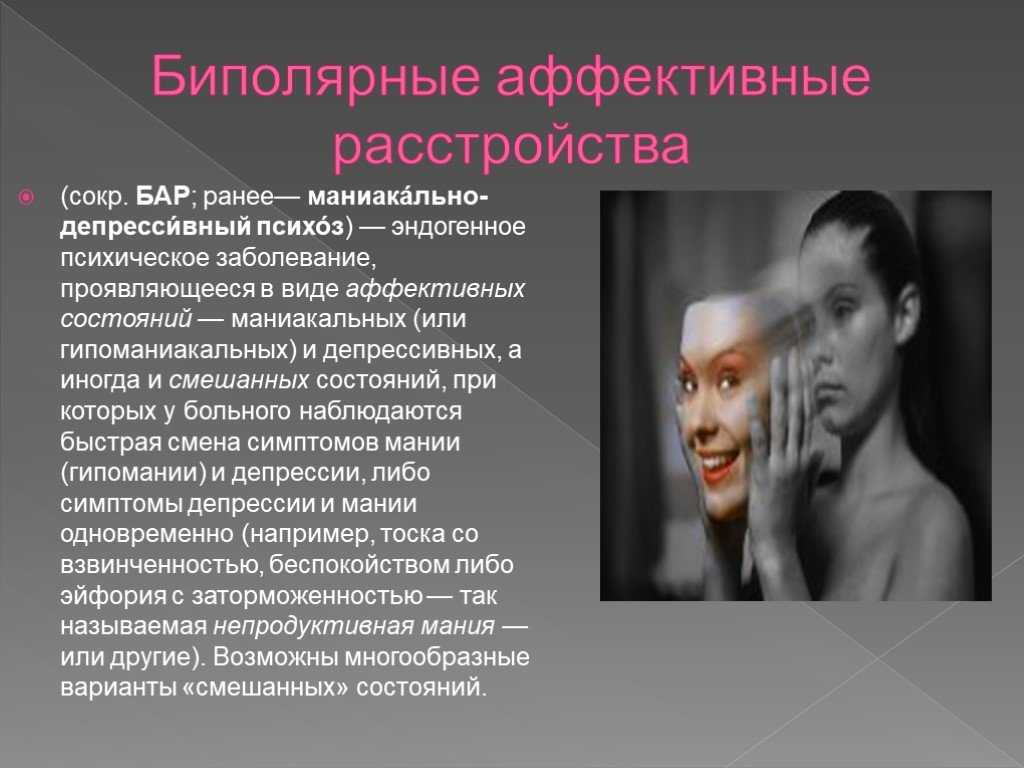

- Schizophrenia has long been equated with a "delusional disorder". But it is now clear that schizophrenia is a progressive disease characterized by multidimensional symptomatology.

In this section:

Patients may complain of various symptoms that reduce their quality of life 1 .![]()

The first manifestations of schizophrenia usually appear in young people between the ages of 16 and 30 2 .

When making a diagnosis, the doctor always evaluates the symptoms. For this, special techniques have been developed. The treatment of schizophrenia is aimed at relieving the symptoms of the disease, including persistent symptoms, and at reducing the risk of adverse drug reactions 3 .

Doctors classify symptoms of schizophrenia into 3 main groups:

positive;

negative;

cognitive.

What does it mean: positive symptoms of schizophrenia?

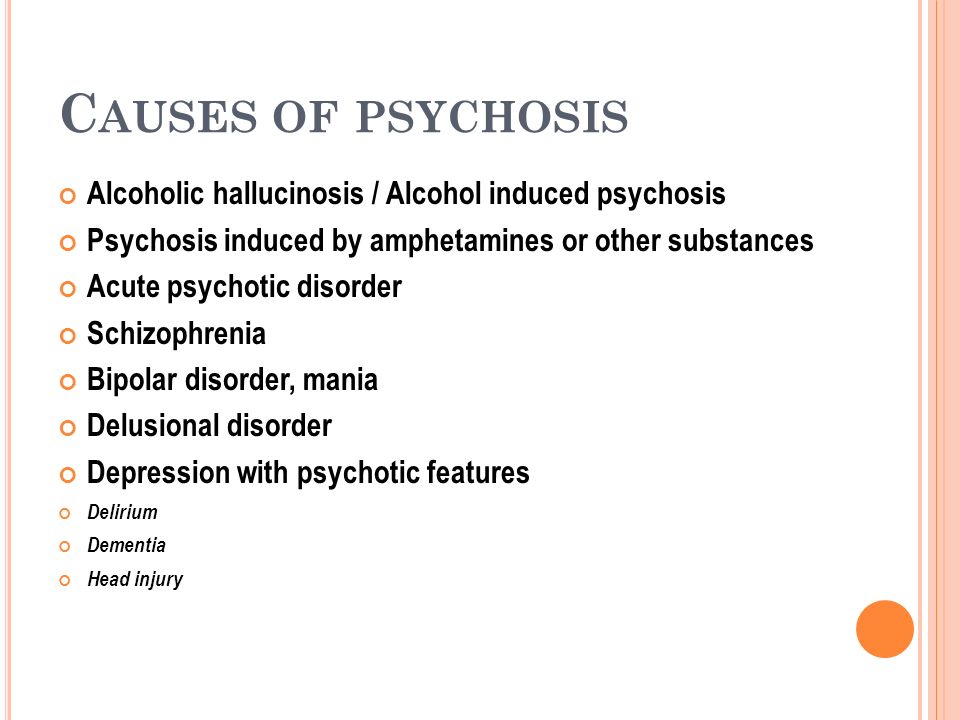

When positive symptoms occur patients develop a feeling of detachment from reality, strange behavior 2 . These sensations may either increase or disappear 2 . Often, when the symptoms are not pronounced, they go unnoticed by others, which can lead to the progression of schizophrenia.

Positive symptoms include:

Hallucinations - a state when a person talks about what he sees, hears, feels the taste of an object that does not exist in reality (there is a sensation, but there is no external stimulus). Frequent complaint of "voices in the head". The condition is dangerous because it can go unnoticed by relatives and friends for a long time 2 , accompanied by unexpected inadequate actions.

Frequent complaint of "voices in the head". The condition is dangerous because it can go unnoticed by relatives and friends for a long time 2 , accompanied by unexpected inadequate actions.

Delusional ideas - patients are unshakably sure of their false conclusions. For example, decide that they are in danger or that all friends and relatives hate them. Although in reality there are no grounds for such conclusions 2 .

Movement disorders - you may notice strange or constantly repetitive movements of the same type, some have a catatonic stupor (complete cessation of movement) 2 .

What does it mean: negative symptoms of schizophrenia?

When negative symptoms predominate, the patient finds himself isolated from society, experiences difficulties in expressing emotions. It is difficult for others to notice the negative manifestations of schizophrenia. They are often confused with depression 2 .

They are often confused with depression 2 .

Negative symptoms include:

Emotional alienation, lack of emotional involvement ( flattening of affect ) 2.4 .

Speech changes, it becomes muffled, inexpressive, even when the conversation is about things that are important for a person ( alogia ) 2,4 .

Inability to enjoy ( anhedonia ) 2.4 .

Social exclusion, denial of even essential daily activities ( asociality ) 2.4 .

Lack of motivation, purposefulness ( apathy) 2.4 .

When diagnosing negative symptoms, the doctor divides them into two subgroups: primary negative symptoms (main symptoms of the disease) or secondary symptoms 5 . To the latter, the doctor will include adverse reactions due to the use of drugs to alleviate the positive symptoms of schizophrenia (extrapyramidal disorders, acute dystonia, parkinsonism), worsening due to the use of illegal substances or depression 5 . Unfavorable external conditions can also provoke the development of secondary negative symptoms: prolonged hospitalization often leads to a subsequent rejection of interpersonal interaction, to social isolation 5 .

Unfavorable external conditions can also provoke the development of secondary negative symptoms: prolonged hospitalization often leads to a subsequent rejection of interpersonal interaction, to social isolation 5 .

What does it mean: cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia?

In some patients, the symptoms are subtle and difficult to diagnose by a doctor, in others, disorders immediately noticeable to the patient and others appear 2 .

Cognitive symptoms include:

Difficulties with concentration, perception of new information, decision-making 2 .

Short-term memory disorders 2 .

When do symptoms of schizophrenia occur?

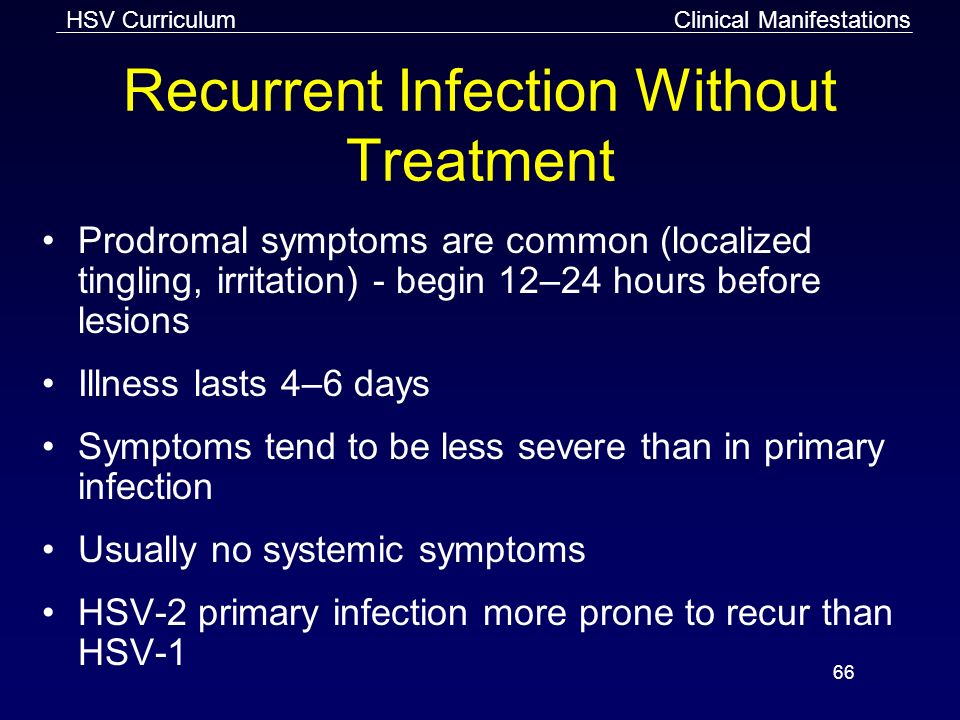

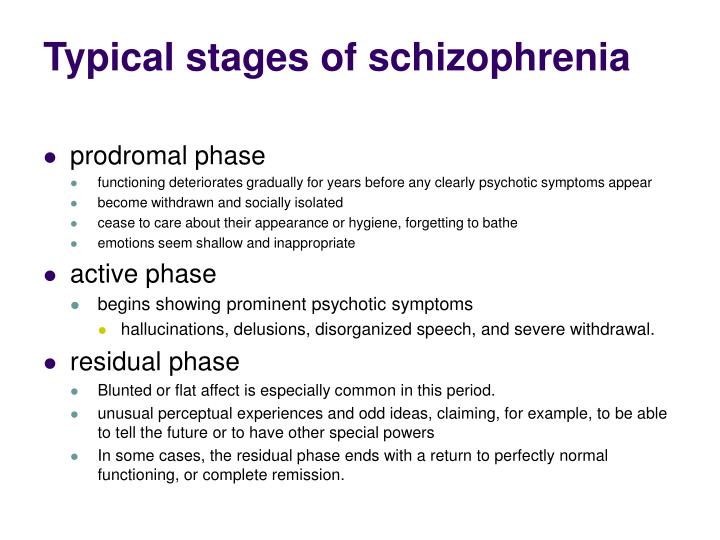

Usually the first signs are observed in the prodromal period, which lasts from a few days to 18 months. A person may note a deterioration in memory, concentration of attention, a decrease in working capacity 6 . The prodromal period is replaced by an episode of acute psychosis. There are delusions, hallucinations, oddities in behavior, constant tension 6 . Psychosis replaces the stage of stabilization of the disease (residual stage). It can last several years and be interrupted by new psychotic episodes. Psychosis can be treated and controlled with modern medications 6 .

The prodromal period is replaced by an episode of acute psychosis. There are delusions, hallucinations, oddities in behavior, constant tension 6 . Psychosis replaces the stage of stabilization of the disease (residual stage). It can last several years and be interrupted by new psychotic episodes. Psychosis can be treated and controlled with modern medications 6 .

This is a very short story about the symptoms of schizophrenia. Each patient has his own unique "set" of symptom complexes 6 . Some people experience positive symptoms for a short period of time, while others suffer from them for many years. In some, psychosis occurs without a prodrome 6 .

But it is important for every patient to start treatment on time.

The development of negative symptoms of schizophrenia (adapted from: Millan et al., 2014)⁷

Learn more about methods for diagnosing schizophrenia.

Sources:

- Arsova S. Open Access Maced J Med Sci.

2016;4(3):388-391

2016;4(3):388-391 - National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/schizophrenia/index.shtml

- National Institutes of Health. Schizophrenia NIH Factsheet 2010: https://report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/viewfactsheet.aspx?csid=67

- Tandon R. Current Psychiatry 2002;1(9):36-42

- Kirschner M. Schizophr Res. 2017; 186:29-38

- NICE CG 178

- Millan et al. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014; 24(5):645-92

Login to Unlock

Schizophrenia: clinical picture

Schizophrenia can manifest itself in different ways. It depends on the personality of the person, the stage of the disease. Information about the stages of development of schizophrenia can help you choose a ver

More…

Login to Unlock

Schizophrenia: treatment and remission

After a diagnosis of schizophrenia is established, the doctor conducts a conversation with the patient about the plan for further treatment

More…

90 does not replace the advice of a healthcare professional.