Parents of children with schizophrenia

Offspring of parents with schizophrenia: mental disorders during childhood and adolescence

. 2004;30(2):303-15.

doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007080.

Sydney L Hans 1 , Judith G Auerbach, Benedict Styr, Joseph Marcus

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, MC3077, 5841 S. Maryland Ave., University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 15279048

- DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007080

Sydney L Hans et al. Schizophr Bull. 2004.

. 2004;30(2):303-15.

doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007080.

Authors

Sydney L Hans 1 , Judith G Auerbach, Benedict Styr, Joseph Marcus

Affiliation

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, MC3077, 5841 S. Maryland Ave., University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 15279048

- DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007080

Abstract

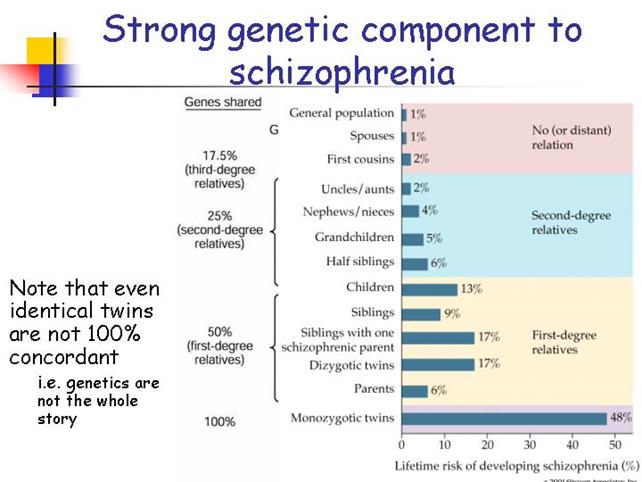

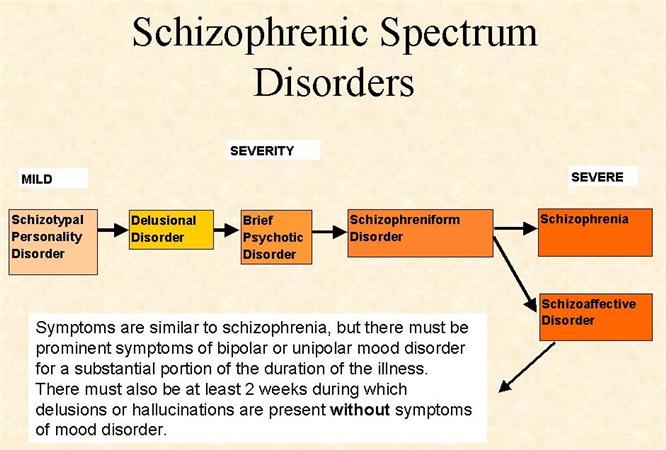

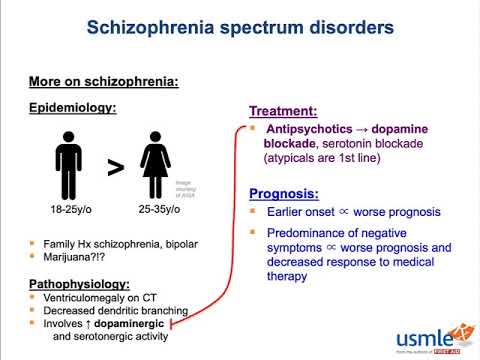

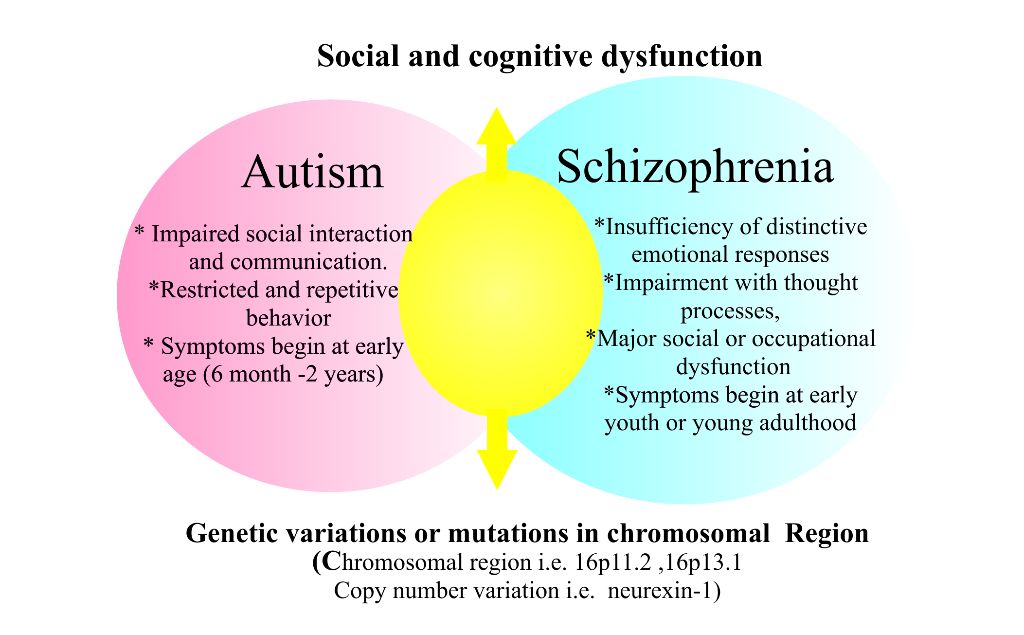

Although offspring of parents with schizophrenia are at risk for schizophrenic illness as adults, little is known about their pattern of symptoms as children and adolescents. Lifetime Axis I and II DSM-III-R diagnoses were made for 116 young people (ages 12-22). Forty-one subjects had a parent with schizophrenia, 39 had a parent with a nonschizophrenic mental disorder, and 36 had parents with no mental illness. Schizophrenia spectrum disorders occurred at higher rates among young people with a parent with schizophrenia (17.1%) than in other young people (5.3%), even after controlling for mental disorder in the nonproband parent. Schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder occurred exclusively in offspring of parents with schizophrenia. Offspring of parents with schizophrenia were also at increased risk for avoidant personality disorder but not paranoid personality disorder. Although lifetime anxiety disorders were common in all young people regardless of parent diagnosis, current anxiety disorders were more prevalent for the adolescent offspring of parents with schizophrenia. These data strongly suggest familial vulnerability to schizophrenia spectrum disorder that is observable before adulthood, particularly for males.

Lifetime Axis I and II DSM-III-R diagnoses were made for 116 young people (ages 12-22). Forty-one subjects had a parent with schizophrenia, 39 had a parent with a nonschizophrenic mental disorder, and 36 had parents with no mental illness. Schizophrenia spectrum disorders occurred at higher rates among young people with a parent with schizophrenia (17.1%) than in other young people (5.3%), even after controlling for mental disorder in the nonproband parent. Schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder occurred exclusively in offspring of parents with schizophrenia. Offspring of parents with schizophrenia were also at increased risk for avoidant personality disorder but not paranoid personality disorder. Although lifetime anxiety disorders were common in all young people regardless of parent diagnosis, current anxiety disorders were more prevalent for the adolescent offspring of parents with schizophrenia. These data strongly suggest familial vulnerability to schizophrenia spectrum disorder that is observable before adulthood, particularly for males.

Similar articles

-

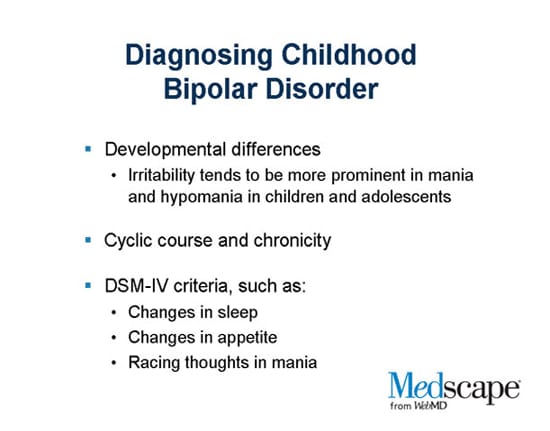

Psychiatric Disorders and Quality of Life in the Offspring of Parents with Bipolar Disorder.

Goetz M, Sebela A, Mohaplova M, Ceresnakova S, Ptacek R, Novak T. Goetz M, et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017 Aug;27(6):483-493. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0056. Epub 2017 Jun 5. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017. PMID: 28581338

-

Avoidant personality disorder is a separable schizophrenia-spectrum personality disorder even when controlling for the presence of paranoid and schizotypal personality disorders The UCLA family study.

Fogelson DL, Nuechterlein KH, Asarnow RA, Payne DL, Subotnik KL, Jacobson KC, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Fogelson DL, et al. Schizophr Res. 2007 Mar;91(1-3):192-9.

doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.023. Epub 2007 Feb 15. Schizophr Res. 2007. PMID: 17306508 Free PMC article.

doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.023. Epub 2007 Feb 15. Schizophr Res. 2007. PMID: 17306508 Free PMC article. -

Childhood anxiety: an early predictor of mood disorders in offspring of bipolar parents.

Duffy A, Horrocks J, Doucette S, Keown-Stoneman C, McCloskey S, Grof P. Duffy A, et al. J Affect Disord. 2013 Sep 5;150(2):363-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.021. Epub 2013 May 23. J Affect Disord. 2013. PMID: 23707033

-

Offspring of Parents with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review of Developmental Features Across Childhood.

Hameed MA, Lewis AJ. Hameed MA, et al. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2016 Mar-Apr;24(2):104-17. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000076. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2016. PMID: 26954595 Review.

-

Children of parents with bipolar disorder.

A population at high risk for major affective disorders.

A population at high risk for major affective disorders. Hodgins S, Faucher B, Zarac A, Ellenbogen M. Hodgins S, et al. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002 Jul;11(3):533-53, ix. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00002-0. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002. PMID: 12222082 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Risk of Disruptive Behavioral Disorders in the Offspring of Parents with Severe Psychiatric Disorders.

Ayano G, Betts K, Maravilla JC, Alati R. Ayano G, et al. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2021 Feb;52(1):77-95. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-00989-4. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2021. PMID: 32291561

-

Psychopathology in 7-year-old children with familial high risk of developing schizophrenia spectrum psychosis or bipolar disorder - The Danish High Risk and Resilience Study - VIA 7, a population-based cohort study.

Ellersgaard D, Jessica Plessen K, Richardt Jepsen J, Soeborg Spang K, Hemager N, Klee Burton B, Jerlang Christiani C, Gregersen M, Søndergaard A, Uddin MJ, Poulsen G, Greve A, Gantriis D, Mors O, Nordentoft M, Elgaard Thorup AA. Ellersgaard D, et al. World Psychiatry. 2018 Jun;17(2):210-219. doi: 10.1002/wps.20527. World Psychiatry. 2018. PMID: 29856544 Free PMC article.

-

Mistrustful and Misunderstood: A Review of Paranoid Personality Disorder.

Lee R. Lee R. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2017 Jun;4(2):151-165. doi: 10.1007/s40473-017-0116-7. Epub 2017 May 18. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2017. PMID: 29399432 Free PMC article.

-

How to support patients with severe mental illness in their parenting role with children aged over 1 year? A systematic review of interventions.

Schrank B, Moran K, Borghi C, Priebe S. Schrank B, et al. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015 Dec;50(12):1765-83. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1069-3. Epub 2015 Jun 20. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015. PMID: 26091723 Review.

-

[Review of risks factors in childhood for schizophrenia and severe mental disorders in adulthood].

Artigue J, Tizón JL. Artigue J, et al. Aten Primaria. 2014 Aug-Sep;46(7):336-56. doi: 10.1016/j.aprim.2013.11.002. Epub 2014 Apr 1. Aten Primaria. 2014. PMID: 24697917 Free PMC article. Review. Spanish.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Grant support

- R01 Mh55208/MH/NIMH NIH HHS/United States

Growing Up with a Parent with Schizophrenia

Home > Featured in Mental Health > Growing Up with a Parent with Schizophrenia

By Kristina Robb-Dover

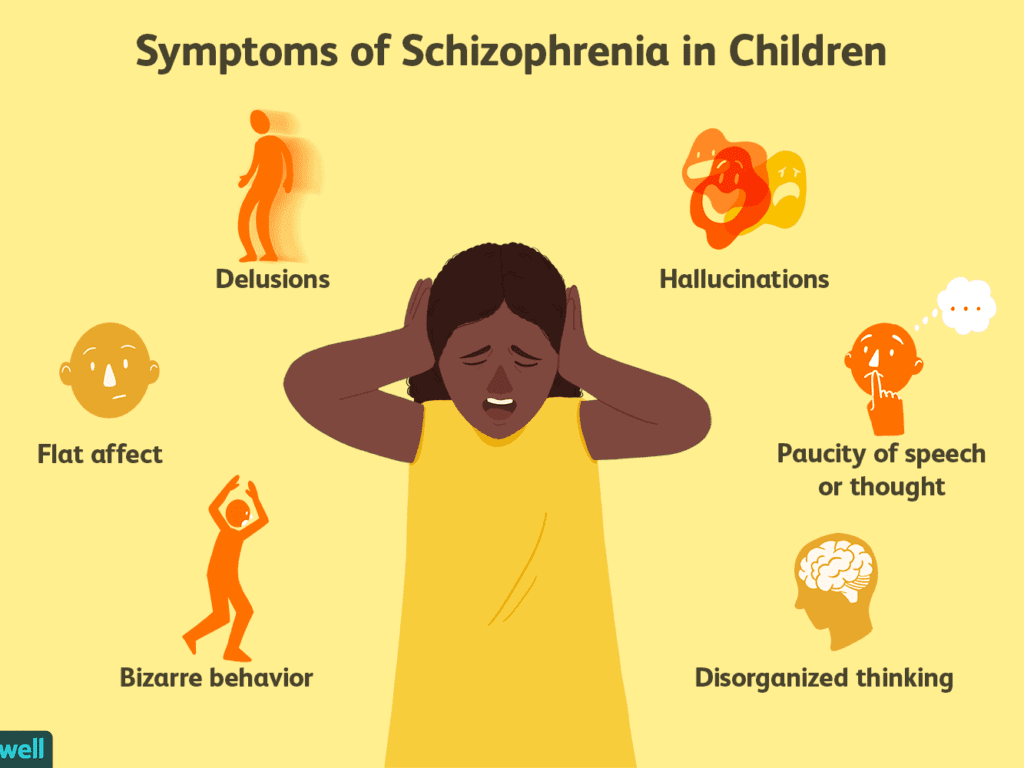

Children who grow up with a parent with schizophrenia have a lack of understanding about the condition. They may ask questions like, “What is schizophrenia like? Why is my mom or my dad acting this way? Is it my fault?” This experience can have long-term impacts on healthy childhood development.

They may ask questions like, “What is schizophrenia like? Why is my mom or my dad acting this way? Is it my fault?” This experience can have long-term impacts on healthy childhood development.

In this piece, we’ll talk about what it’s like to be schizophrenic and the challenges a parent with this mental health condition faces when raising children. We’ll also talk about potential consequences on children in the long run and why it’s so important to get help.

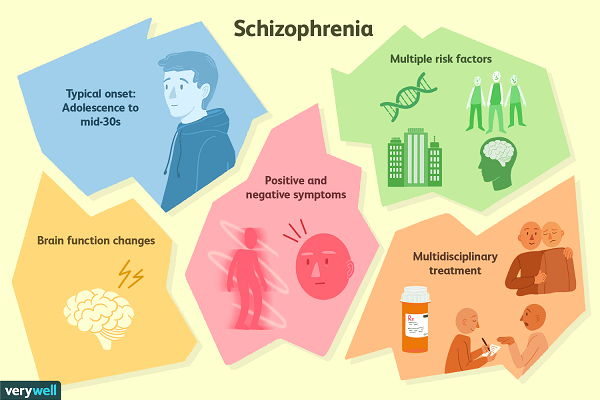

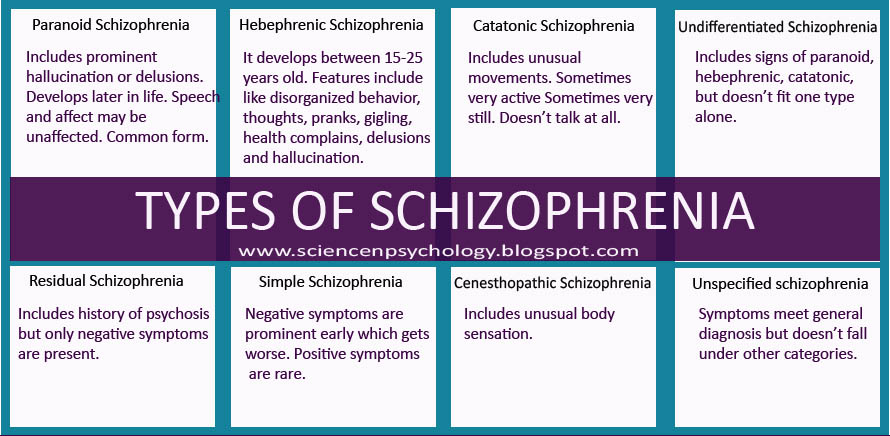

Understanding Schizophrenia

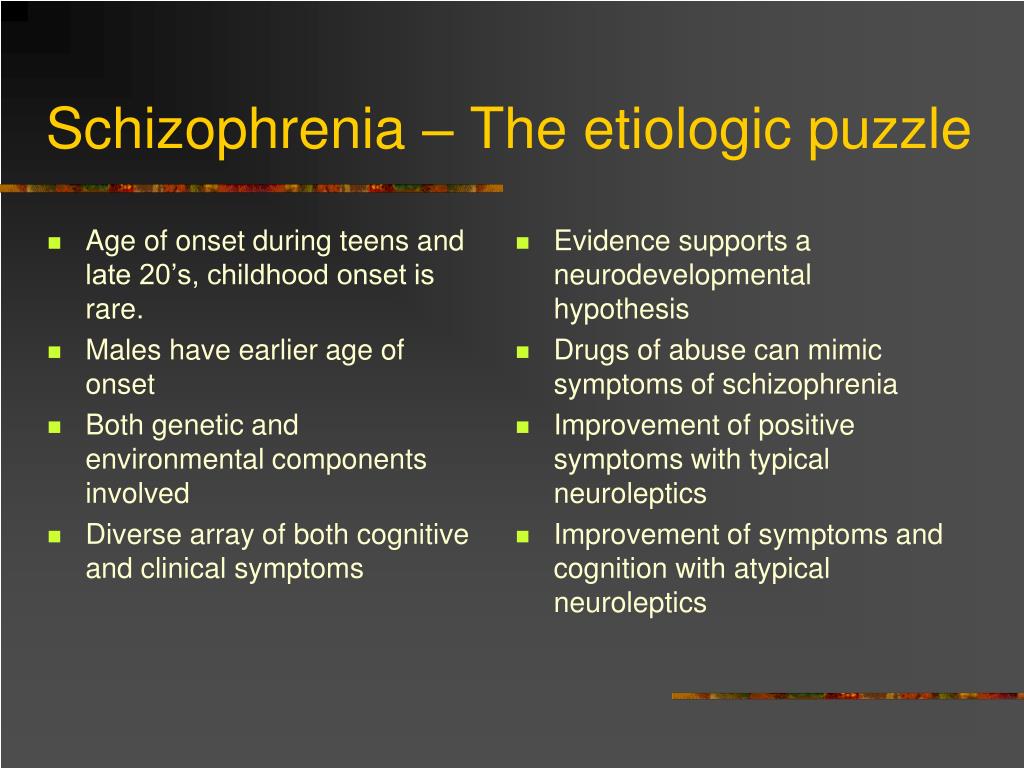

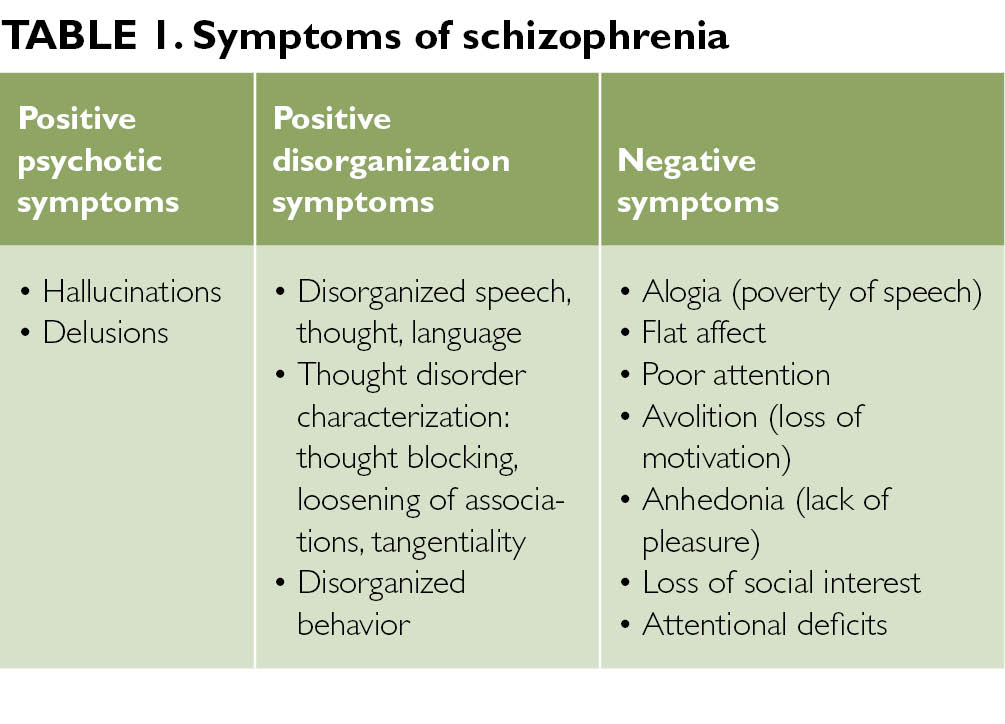

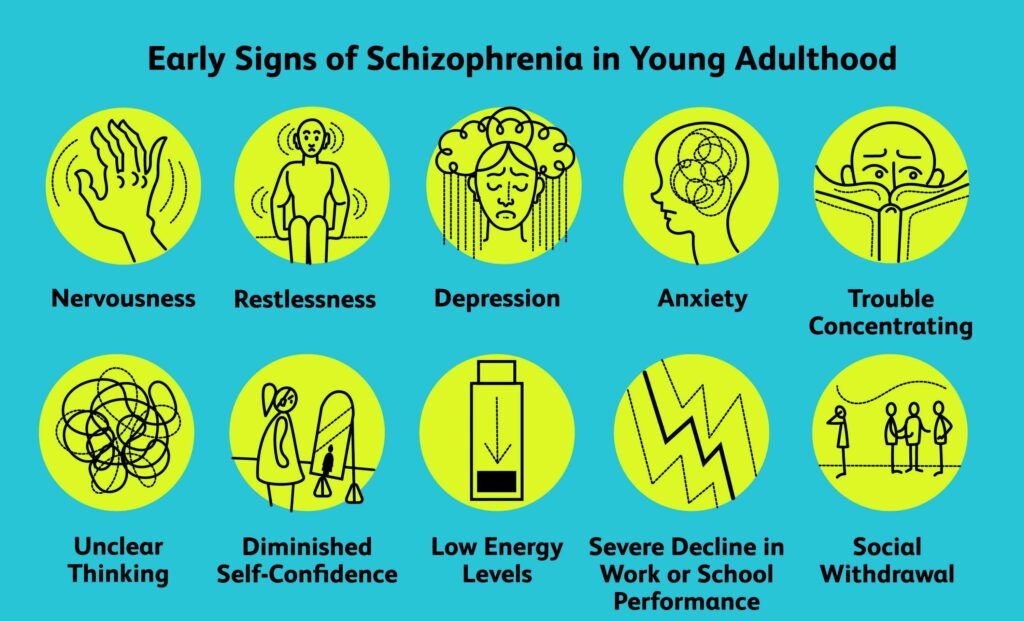

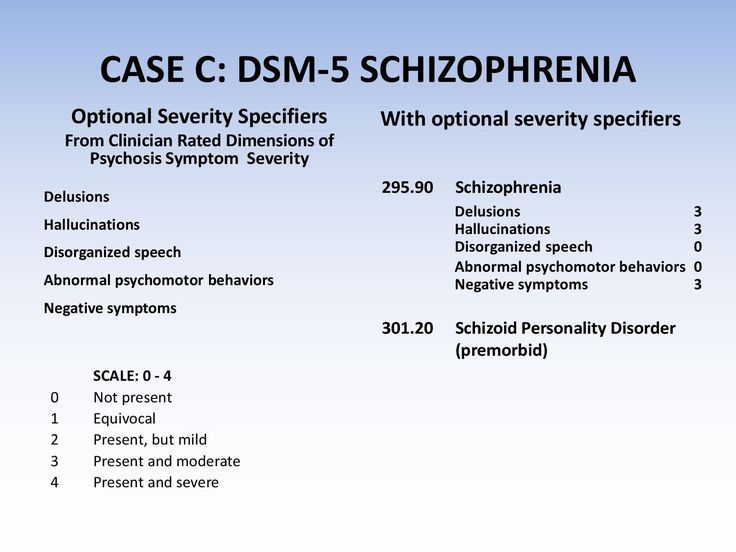

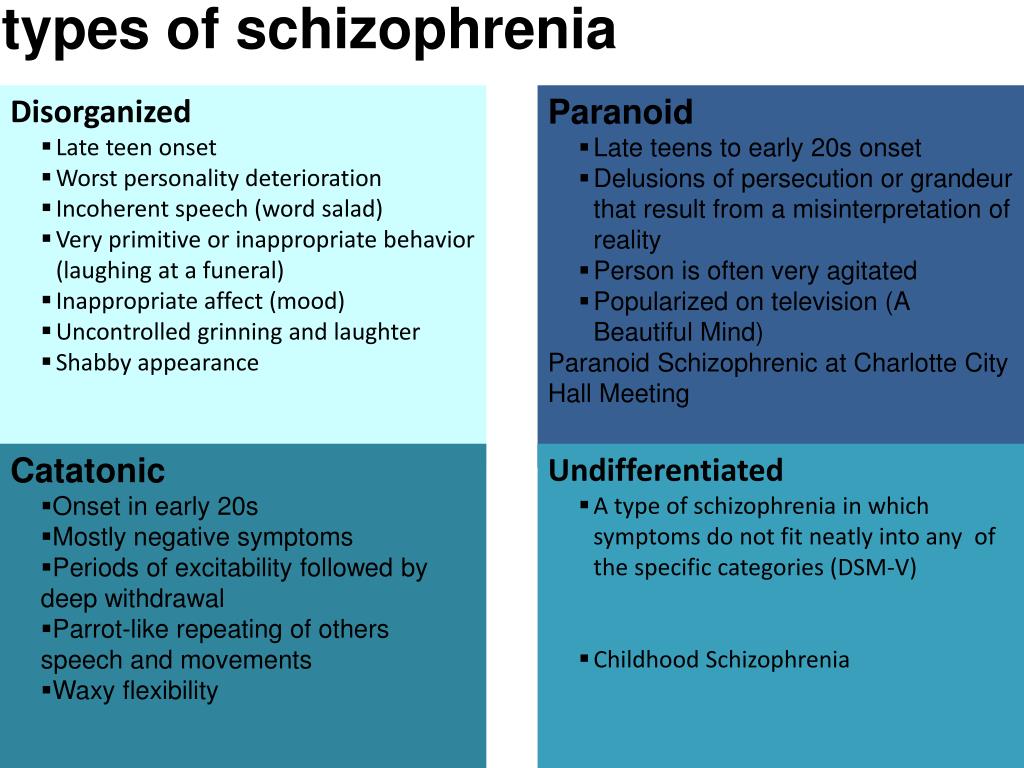

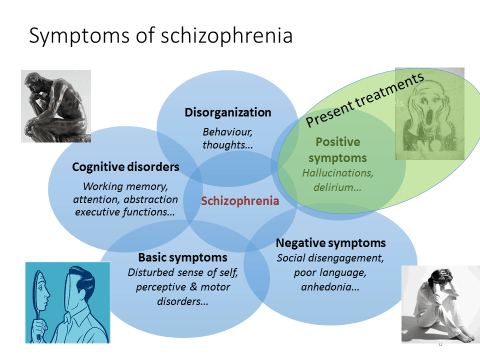

What is schizophrenia like? The fact that this disease is not well understood makes it difficult to diagnose and treat effectively. There are several types of schizophrenia, and while the disease is marked by several telltale signs when it’s at its most severe, early signs can be hard to pin down.

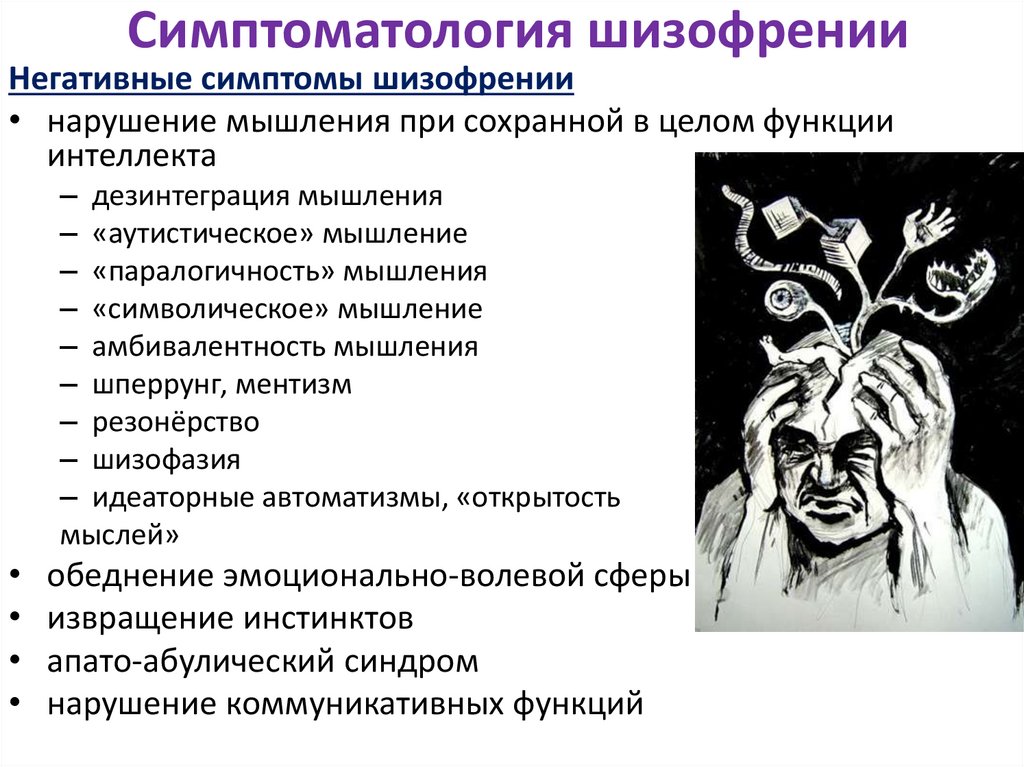

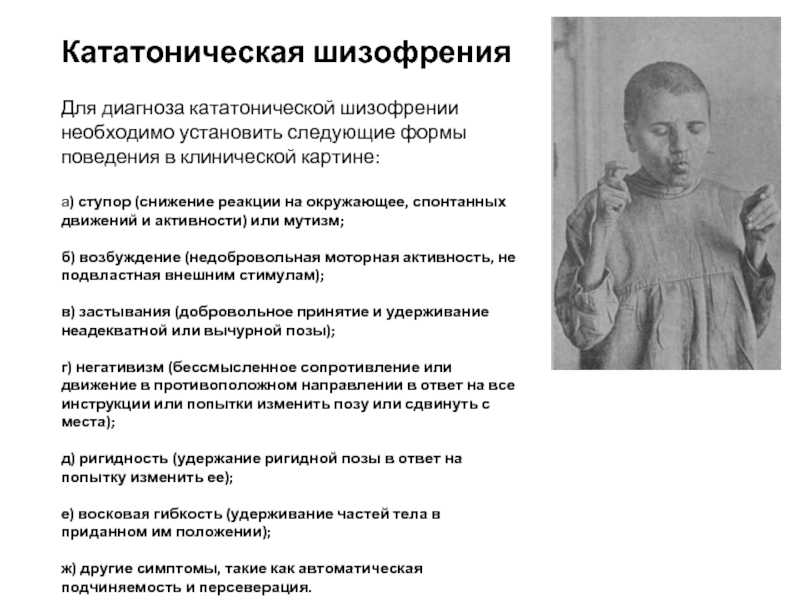

A person with schizophrenia will often experience delusions or full-blown hallucinations, seeing and interacting with people who aren’t there. They may also suffer from disorganized thinking or speech, saying things that don’t make sense to other people. They’re often extremely paranoid because of their delusions, thinking other people are conspiring to hurt them. They may even become a danger to those around them. Untreated schizophrenia can make it extremely difficult to live a healthy, enjoyable life because its effects can be constant.

They’re often extremely paranoid because of their delusions, thinking other people are conspiring to hurt them. They may even become a danger to those around them. Untreated schizophrenia can make it extremely difficult to live a healthy, enjoyable life because its effects can be constant.

What Is Schizophrenia Like for a Parent?

Understanding what schizophrenia is like helps to explain why people with conditions like these have a difficult time providing a stable environment to raise a child.

A parent with untreated schizophrenia may have difficulty providing for their child’s basic needs, like food, transportation to school and educational enrichment. Often, people with schizophrenia perceive the people around them as threats and lash out or, in extreme cases, try to harm their loved ones or themselves. It goes without saying that this is far from a healthy environment for a child. They may internalize their parent’s behavior as something they caused, which can have long-term effects on their self-esteem and healthy development.

All of this can affect the future outcomes of the child, even if there’s another parent or guardian in the household who can help.

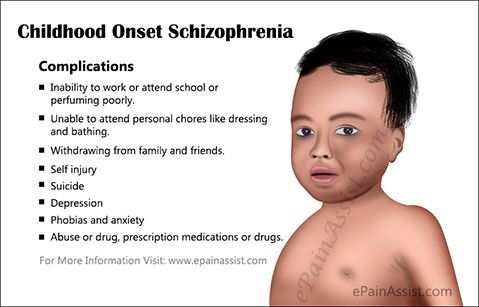

Long-Term Effect of Schizophrenia on Children

What are the consequences of being raised by a parent battling a severe psychological condition like schizophrenia? Studies show these children suffer worse outcomes than their peers, lagging in social and academic development at an early age. Children with a schizophrenic mother were more likely to face negative effects because of the importance of the maternal bond in early development. These children are more likely to develop mood disorders like depression and anxiety as they get older.

Living with a parent who suffers from a mental disorder is classified as an adverse childhood experience (ACE). This is a category of childhood trauma that’s heavily linked with consequences lasting into adulthood. Children who experience ACEs growing up are more likely to struggle with employment, experience financial insecurity and face substance abuse or mental health issues themselves.

Steps to Take to Resolve Trauma Caused by a Schizophrenic Parent

As a result of their condition, the actions of a schizophrenic parent may be categorized as abuse or neglect because of the way their children are affected. That’s why it’s critically important to seek help as soon as possible.

What a Parent With Schizophrenia Can Do to Mitigate Damage Done

If you’re struggling to control schizophrenia or a similar disease and worried about how it’s affecting your children, you’re not alone. Many people with mental and behavioral health issues have to reconcile with the ways their conditions make it difficult to manage their responsibilities as a parent. There are steps you can take to make sure your schizophrenia feelings don’t do long-term damage to your child, their healthy development and your relationship with them in the long run.

Seeking Help for Yourself or a Loved One With Schizophrenia

The first step is to get the help you need. This means immediate, often intensive, psychological care. In many cases, people with schizophrenia can manage their symptoms using a combination of therapy and medication, but no two cases are exactly alike, and it may take time to find a treatment plan that works for you.

In many cases, people with schizophrenia can manage their symptoms using a combination of therapy and medication, but no two cases are exactly alike, and it may take time to find a treatment plan that works for you.

However, those who understand what it’s like to be schizophrenic know that even making the decision to get help is often easier said than done. People who experience this illness often can’t come to terms with the need to get help because they’re having trouble thinking clearly and perceiving reality. If you have a loved one suffering from schizophrenia, make sure they have access to effective care to the extent of your capabilities. Here are some tips for supporting someone you live with who has schizophrenia.

Getting Your Child the Help They Need

It’s also important to make sure children have access to the support they need while their parent is beginning and undergoing treatment for schizophrenia. This can come in the form of a professional child psychologist the child can talk to about the challenges of living with a schizophrenic parent and other issues they may not be able to talk about with that parent due to their condition.

Many children in this situation can also find stability with other family members. In a study examining the long-term effects of growing up with a parent with schizophrenia, 84% of respondents said forming a supportive relationship with at least one other family member made them more resilient.

Getting Help at FHE Health

If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with schizophrenia, it’s important for everyone involved that you seek help as soon as possible. At FHE Health, we offer intensive treatment programs for a wide range of mental health conditions. If you know what schizophrenia is like, you know how much the right mix of medications, therapies and other treatments can make a difference for a person suffering from this complex disease. Reach out today and learn more about the options we offer.

Filed Under: Featured in Mental Health, Behavioral & Mental Health

About Kristina Robb-Dover

Kristina Robb-Dover is a content manager and writer with extensive editing and writing experience. .. read more

.. read more

The story of schizophrenia in a model family: an excerpt from Something Wrong with the Galvins

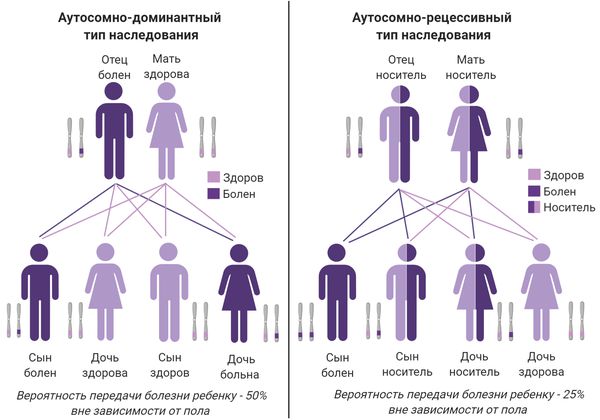

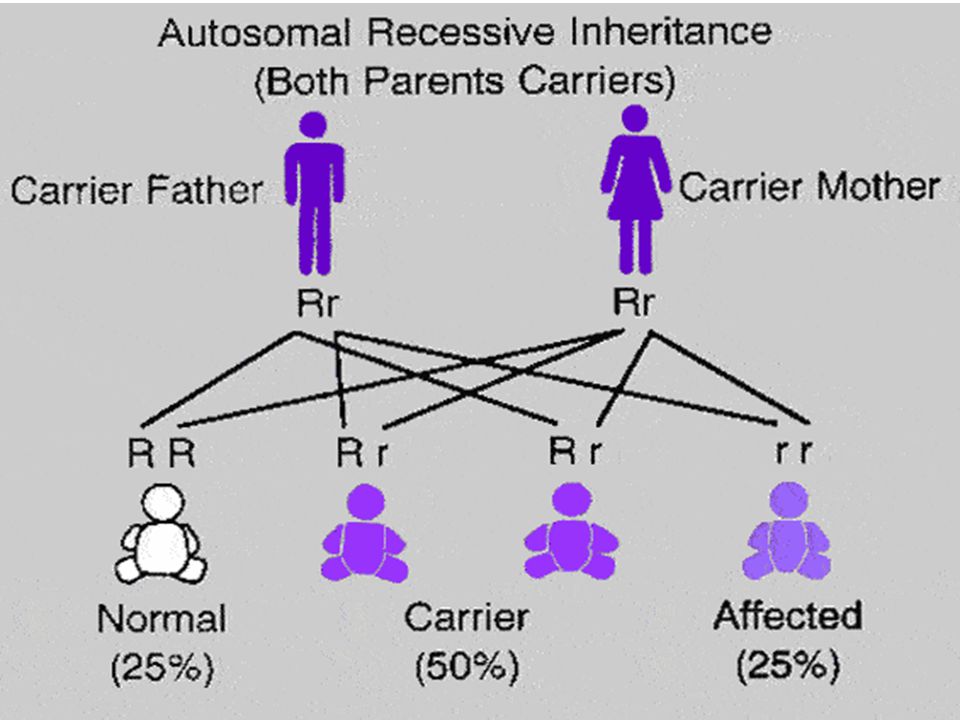

For a long time, researchers believed that this disease was genetic and inherited. However, it was the study of this case that led to the opposite conclusions, because the parents were absolutely mentally healthy. They tried to pay equal attention to all children, give them a good education, played music and sports with them. But, despite all this, in the end they could not prevent the sad development of events in any way and were forced to helplessly watch the illness of their children. nine0005

"Something Wrong with the Galvins. An Ideal Family Destroyed by Madness" (Bombora Publishing House) by American journalist Robert Kolker is a book about the history of this family, about how Don and Mimi noticed for the first time that something was wrong with their son as they tried to deal with it. In parallel, the book tells about how the study of the disease took place, what methods were used to treat patients, and what results the study of the Galvin case led to. Read a short passage about Jim, the second son of Don and Mimi, who suddenly began to hear voices and show aggression towards his wife Kathy. nine0005

Read a short passage about Jim, the second son of Don and Mimi, who suddenly began to hear voices and show aggression towards his wife Kathy. nine0005

Read also

Is depression and schizophrenia possible? In a sense, yes

After studying in Boulder for about two years (and becoming a regular at several of the local bars), Jim met Cathy. He was twenty, she was nineteen. He drew attention to her at a dance at Giuseppe's restaurant. She came with a classmate friend, and Jim asked permission to join them. Then he called her at home (she lived with her parents), and they began to meet. nine0007

From the beginning, Cathy noticed Jim's dislike for his parents. "So many children have been cut that they can't cope with the little ones," he once said. He also liked to complain about his hated older brother - they say that he was considered a hero in high school, and they took me for some kind of half-wit. The girl decided that all this, probably, was already in the past for him, at least it should have become one.

When Cathy became pregnant, Jim did not hesitate to ask her to marry him. Such an outcome hardly looked ideal from the point of view of Don and Mimi, although, in truth, at Jim's age, they themselves did almost the same thing. In any case, it was useless to say anything. This is Jim, who will definitely do what he wants. In addition, they had just blessed Donald's marriage, and they had no weighty arguments left. nine0007

The wedding took place in August 1968, a year after the marriage of Donald and Jean. The newlyweds settled in a small one-story red brick house in the city center. From time to time they invited the Jim brothers to visit - everyone except Donald, just not Donald. Cathy got along well with her younger brothers Galvin, but she had a strained relationship with Jim's mother. Mother-in-law's visits were more like inspections. "You haven't dusted," Mimi said, to which Cathy replied, "I don't have time. There's a rag over there if you want to get busy." Jim was delighted with such dialogues. Katie gave birth to a son, Jimmy, who was only a couple of years younger than Mary, Mimi's youngest daughter. Jim dropped out of school and began working as a bartender at parties. This did not fit in with his former goal of becoming a teacher, like his father. But the main thing was different: now Jim became the father of the family and believed that he had surpassed Donald in all respects. Having landed a full-time job as a bartender at the Broadmoor Hotel, one of the city's most prestigious locations, he felt like a clear winner. nine0007

Katie gave birth to a son, Jimmy, who was only a couple of years younger than Mary, Mimi's youngest daughter. Jim dropped out of school and began working as a bartender at parties. This did not fit in with his former goal of becoming a teacher, like his father. But the main thing was different: now Jim became the father of the family and believed that he had surpassed Donald in all respects. Having landed a full-time job as a bartender at the Broadmoor Hotel, one of the city's most prestigious locations, he felt like a clear winner. nine0007

Jim enjoyed his role as husband and father, but never missed an opportunity to break his marriage vows. Being an incorrigible womanizer before marriage, he saw no reason to improve in this regard after her.

Read also

It seems that people have two selves, and one gives meaning to life. Excerpt from a book about dying

One evening Cathy noticed his motorcycle at the entrance to a bar. She went in, saw Jim and his girlfriend, poured beer over them from a carafe on the table, and left. She wanted Jim to understand that she had her own pride. Jim got even with her later, when they were alone. Hearing that Cathy had quit her job and wanted to continue her teacher education, he removed the spark plugs from the car's engine to prevent her from going to school. "Go to work," he said. When Cathy arranged for her mother to pick her up, he waited for her to return and slapped her. nine0007

She wanted Jim to understand that she had her own pride. Jim got even with her later, when they were alone. Hearing that Cathy had quit her job and wanted to continue her teacher education, he removed the spark plugs from the car's engine to prevent her from going to school. "Go to work," he said. When Cathy arranged for her mother to pick her up, he waited for her to return and slapped her. nine0007

Jim became more and more aggressive, and Cathy realized that it was better not to threaten him with leaving. Once she tried it and got hit in the head so hard that she needed stitches. Besides, she couldn't bring herself to carry out that threat. Every time she was on the verge of leaving, she thought that Jim could improve and that their son needed a father. On the rare occasions when Katie got up the nerve to leave home for a day or two, Jimmy would whine, "I want to go home to my dad." nine0007

There was another reason Katie didn't want to leave him. She began to notice that Jim was tormented by something that had nothing to do with her, and this made her feel something like pity for him. He heard some voices. "They were talking to me again," Jim whispered. In a stifled voice from overflowing emotions, he talked about them - some people who spy on him, follow on his heels and plot intrigues at work.

He heard some voices. "They were talking to me again," Jim whispered. In a stifled voice from overflowing emotions, he talked about them - some people who spy on him, follow on his heels and plot intrigues at work.

Jim stopped sleeping. All night long he stood at the gas stove, turning the oven on and off and on again. In such states, he was capable of reckless and ruthless acts not in relation to Cathy and his son, but to himself. nine0007

While walking through downtown Colorado Springs, Jim suddenly started banging his head against a brick wall. On another occasion, he dived into the pond fully clothed. The first time Jim was hospitalized for a psychotic break was on Halloween Eve 1969, when Jimmy was still an infant. He was admitted to the hospital of St. Francis, from where he fled the very next day. Katie was afraid for herself and for her son, but she was afraid for Jim too. Yet he was the husband, the father of her child, and leaving him now seemed unthinkable. nine0007

See also

US Air Force patents DNA test for intelligence. Ahead of the future, they bring back the gloomy past

Ahead of the future, they bring back the gloomy past

Jim's parents never liked Kathy (which was fine with Jim himself), but she knew she had to tell Don and Mimi about what had happened. Their reaction startled her. She expected to see tears, compassion, or at least understanding. Instead, two people sat in front of her, desperately trying to pretend that they did not hear anything special, and in response to the insistence on continuing the conversation, they questioned its essence. Did it really happen exactly as Kathy said? Jim's parents were completely unwilling to accept that their son was in trouble or even in danger. On the contrary, they presented what happened as a marital problem of a young couple, which Jim and Kathy should try to solve on their own. Perhaps most notable, at least in retrospect, was Don and Mimi's silence about Jim's brother Donald acting weird too. They did not tell anyone about the eldest son and were not going to share this with Cathy. nine0007

After talking to Don and Mimi, Cathy, on their advice, took Jim to the priest, but it was no use. One evening, when Jim seemed completely helpless, Kathy finally took him to the University of Colorado Hospital in Denver. He stayed there for two months and returned home. Jim agreed to receive outpatient care at Pikes Peak Asylum in Colorado Springs. The doctor gave him medication, and his condition remained stable long enough to give him some hope. nine0007

One evening, when Jim seemed completely helpless, Kathy finally took him to the University of Colorado Hospital in Denver. He stayed there for two months and returned home. Jim agreed to receive outpatient care at Pikes Peak Asylum in Colorado Springs. The doctor gave him medication, and his condition remained stable long enough to give him some hope. nine0007

Only from time to time he lost his temper and beat Cathy again. One day a policeman came to see them, but Cathy refused to prosecute. On another occasion, policemen called by neighbors escorted Jim out of the house.

True, after a while he returned. Jim always came back, no matter what happened. In later years, Don and Mimi never interfered. “Except for the cases when Jim dumped and returned to live with them, which suited me very much. Well, then he reappeared on the threshold of my house,” recalls Cathy. nine0007

See also

A brief history of the "improvement" of humans and the human race. Eugenics before and after the Nazis

On a spring day in 1969, all twelve of the Galvin children gathered in a relatively peaceful and friendly atmosphere to honor their father in a ceremony at the University of Colorado. At the age of forty-four, Don finally received his degree. The picture taken that day is perhaps the only photograph in which all twelve children and both of their parents are present. Don with already touched with gray hair in a mantle and an academic cap. Next to him is Mimi with slicked back hair, in a cream spring dress with a bright yellow scarf. In front of their parents are the girls, Margaret and Mary, in identical white dresses. And on the right, all ten boys lined up in two rows, like skittles. nine0007

At the age of forty-four, Don finally received his degree. The picture taken that day is perhaps the only photograph in which all twelve children and both of their parents are present. Don with already touched with gray hair in a mantle and an academic cap. Next to him is Mimi with slicked back hair, in a cream spring dress with a bright yellow scarf. In front of their parents are the girls, Margaret and Mary, in identical white dresses. And on the right, all ten boys lined up in two rows, like skittles. nine0007

Fourth from the left in the second row is Jim with tousled dark hair and a pale sweaty face. In the future, Mimi will show this photo more than once, saying that in that one of the last carefree happy days of the family, she first realized that Jim was in big trouble - now he is not just a rebel, as he always was, but a madman. Like Donald.

Tags:

Fragments of new books

The burden borne by family members of schizophrenic patients ("family burden")

The article presents a review of foreign literature reflecting the history of the issue, the formation of the concept of "family burden" and the results of research in this area.

Background to the study of the burden of the mentally ill in the family and the definition of the term "family burden"

Purposeful study of the family as a structure that reacts to the presence of a mental illness in its member began with the work of sociologists and social psychologists in the middle of the last century. The study of the reactions of family members to the mental illness of a relative was caused by theoretical interest in emerging in 1950s to such concepts of social psychology as "social perception" (social perception) and "deviance and social control" (deviance and social control). They described the mutually conditioned perception of social objects and control, the efforts of others to prevent deviant behavior. The practical aspect of attention to the families of the mentally ill was the need to evaluate the effectiveness of community care programs that were innovative for that time, addressed not only to patients, but also to relatives of patients, who began to be considered both as participants in the rehabilitation process and as carriers of the burden of the family. [4]. nine0007

[4]. nine0007

The term "burden on the family" was first introduced in 1946 by the American sociologist M. Bosworth Treudley [68], by which she understood the complex of negative consequences caused by the need to live and care for a mentally ill family member. After a short time, this term changed and took the form of a stable phrase "family burden" (family burden). Later, other terms were proposed to refer to the totality of factors that affect relatives living with a mentally ill family member, for example, “disturbance caused by the patient” [5] or “caregiving consequences” (caregiving). consequences) [74]. More recently, the term caregiver burden has been used. However, its meaning is narrower, since it implies that only the main caregiver of the patient has the burden of caring for the patient, and does not affect the consequences of coexistence with the mentally ill for other family members [60]. Therefore, the term “burden of care” is most often used to refer to the physical, psychological, social and financial problems that arise in caregivers of patients with various types of dementia or other mental pathologies of advanced age [16, 52]. The term "family burden" is not accepted favorably by all professionals. In particular, G. Szmukler [63] characterizes the term “family burden” as unacceptable and pejorative, reflecting exclusively negative aspects, and suggests instead a more neutral, from his point of view, term “caregiving process” or “caregiving process” . nine0007

The term "family burden" is not accepted favorably by all professionals. In particular, G. Szmukler [63] characterizes the term “family burden” as unacceptable and pejorative, reflecting exclusively negative aspects, and suggests instead a more neutral, from his point of view, term “caregiving process” or “caregiving process” . nine0007

L. Fox [13] offered options such as "inconvenience" (inconvenience) or "distress" (distress), arguing her proposals by the fact that the concept of "burden" is difficult for the patient himself, who is unlikely to want other members families perceived him solely as a burden.

Highlighting the main thing in the definitions of the term "family burden" of various researchers, we can say that family burden is the difficulties and suffering caused by the mental illness of a family member experienced by the patient's relatives living with him, who are responsible for the patient and / or emotionally attached to him. nine0007

The first studies on the family burden of relatives of the mentally ill were carried out by English psychiatrists J. Grad and P. Sainsbury [20, 21], who studied the impact of a mentally ill family member on living conditions, relationships with neighbors, social activity, leisure and the physical health of his relatives. In 1966, the classic work of J. Hoenig and M. Hamilton [30] was also published, who proposed the division of the family burden of relatives of the mentally ill into objective and subjective. Under the objective burden began to understand the daily practical problems of relatives of patients, restrictions in their professional activities and social activity, additional financial costs and restrictions, disruption of daily family functioning as a result of a family member's mental illness. The subjective burden began to include the negative psychological impact exerted by the mental illness of a family member on their relatives in the form of their characteristic feelings and experiences, as well as the relatives' subjective perception of the gravity and burdensomeness of the situation, implying their own assessment of their experiences and feelings.

Grad and P. Sainsbury [20, 21], who studied the impact of a mentally ill family member on living conditions, relationships with neighbors, social activity, leisure and the physical health of his relatives. In 1966, the classic work of J. Hoenig and M. Hamilton [30] was also published, who proposed the division of the family burden of relatives of the mentally ill into objective and subjective. Under the objective burden began to understand the daily practical problems of relatives of patients, restrictions in their professional activities and social activity, additional financial costs and restrictions, disruption of daily family functioning as a result of a family member's mental illness. The subjective burden began to include the negative psychological impact exerted by the mental illness of a family member on their relatives in the form of their characteristic feelings and experiences, as well as the relatives' subjective perception of the gravity and burdensomeness of the situation, implying their own assessment of their experiences and feelings. nine0007

nine0007

Family burden prevalence

The prevalence of family burden among relatives of patients with schizophrenia can be as high as 83% [40]. Different rates of family burden depend on a number of specific factors.

First of all, it should be noted that the prevalence of family burden of relatives, although very high, does not equal 100%, and this may be due to the fact that patients with schizophrenia are fundamentally able to positively influence the indicators of the family burden of their relatives. For example, relatives can receive practical and/or emotional support from patients in the form of performing routine household chores, making necessary purchases, being able to listen and give useful advice [23]. In a survey of 121 relatives of patients with schizophrenia [76], it was found that although 31.1% of relatives could not report any support from patients, 34.5% experienced genuine pleasure in communicating with patients, and 11.8 % received practical help from them. Also affecting the prevalence of family burden is the factor of cohabitation or separation with the patient. In a number of studies [25, 56, 59, 76] found that the number of hours per day or week spent with a relative with schizophrenia was positively correlated with both the severity and prevalence of family burden. In turn, the joint or separate residence of relatives with a family member with schizophrenia is subject to a significant influence of the cultural characteristics of a particular country of residence and interethnic differences. Thus, according to a cross-cultural study [70], in the Italian city of Bologna, more than 70% of relatives lived with a sick family member, and only 17% in the American city of Boulder. The results of another study [33] showed that in the state of Ohio (USA), 85% of Hispanics lived with a family member with schizophrenia, while the same indicator for Euro-Americans was only 40%. At the same time, the percentage of relatives living together with a patient with schizophrenia in Germany or England turned out to be almost identical - 64 and 69%, respectively [56].

Also affecting the prevalence of family burden is the factor of cohabitation or separation with the patient. In a number of studies [25, 56, 59, 76] found that the number of hours per day or week spent with a relative with schizophrenia was positively correlated with both the severity and prevalence of family burden. In turn, the joint or separate residence of relatives with a family member with schizophrenia is subject to a significant influence of the cultural characteristics of a particular country of residence and interethnic differences. Thus, according to a cross-cultural study [70], in the Italian city of Bologna, more than 70% of relatives lived with a sick family member, and only 17% in the American city of Boulder. The results of another study [33] showed that in the state of Ohio (USA), 85% of Hispanics lived with a family member with schizophrenia, while the same indicator for Euro-Americans was only 40%. At the same time, the percentage of relatives living together with a patient with schizophrenia in Germany or England turned out to be almost identical - 64 and 69%, respectively [56].

Family burden indicators

Many papers have described in detail the subjective and objective manifestations of family burden in relatives whose family members suffer from various mental disorders. Relatives of patients with schizophrenia have repeatedly described a spectrum of experiences, consisting of feelings of guilt and self-condemnation, shame and embarrassment, fear and confusion, emotional stress and exhaustion, anxiety and depressive reactions [1, 27, 31, 46]. It was found that negative experiences for relatives of patients with schizophrenia have different significance. Among the indicators of subjective burden, the most significant experiences for relatives are anxiety and concern about the general state of his health, safety and his future, and the least significant are the need to control the intake of medications, the patient's sleep and behavioral disorders [26, 56, 57, 73] . nine0007

Some studies [45, 78] have found no difference in quantitative measures of the severity of the family burden depending on whether the affected family member suffers from schizophrenia or affective psychosis. However, the results of other studies [7, 33] indicate that the severity of the family burden of relatives is most pronounced in schizophrenia.

However, the results of other studies [7, 33] indicate that the severity of the family burden of relatives is most pronounced in schizophrenia.

The most important component of both the subjective and objective burden of relatives of patients with schizophrenia is their stigmatization. The process of stigmatization, when a person is stigmatized due to proximity or association with another stigmatized person, has been called "associative stigma" [44]. The consequences of the phenomenon of "associative stigma" for relatives of patients are varied and can be expressed, for example, in the fact that parents of patients with schizophrenia feel shame and guilt (due to the prevailing public opinion about the role of parents in the origin of their child's mental illness), which are joined by low self-esteem , violation of intra-family relationships, difficulties in maintaining existing relationships with family friends, social isolation [69]. According to one study [35], from 25 to 50% of relatives of patients in their social environment try to avoid talking about the presence of a mental illness in a family member in order to “not lose face” [8], and the feelings associated with a possible stigmatization of relatives, form in them appropriate reactions of distancing, avoidance and isolation [19]. The severity of “associative stigma” is evidenced by the results of a special study carried out in Sweden [48] on the impact of associative stigmatization on 162 relatives of patients (69% of relatives were parents, spouses or children) who were in an acute psychotic state. It was found that 18% of relatives had thoughts that it would be better if their sick family member died, and 10% reported that they themselves had suicidal thoughts.

The severity of “associative stigma” is evidenced by the results of a special study carried out in Sweden [48] on the impact of associative stigmatization on 162 relatives of patients (69% of relatives were parents, spouses or children) who were in an acute psychotic state. It was found that 18% of relatives had thoughts that it would be better if their sick family member died, and 10% reported that they themselves had suicidal thoughts.

The family burden that the relatives of the mentally ill bear affects not only their mental sphere, in the form of the subjective experiences and feelings described above, but also negatively affects their physical health [61]. Among the objective indicators of the family burden of relatives of the mentally ill, there were feelings of poor physical health, an increased number of visits to the therapist, and an increased risk of hospitalizations in somatic hospitals [14, 65]. When comparing the physical health indicators of 30 mothers who lived with their adult children with schizophrenia and 263 mothers whose adult children did not have mental illness, the first group showed a higher incidence of somatic disorders in the form of arterial hypertension, arthritis and ophthalmic pathology [ 38]. A special comparison of the physical health of mothers and fathers of sick children [62] showed that the somatic health of fathers is better than that of mothers. In another comparative study [17], 31% of fathers with schizophrenia rated their physical health as unsatisfactory, compared with 6% of fathers whose children did not have mental illness. In addition to somatic pathology, relatives and caregivers of patients with schizophrenia were also found to have an increased frequency of infectious diseases, which was predicted by the severity of positive symptoms in a mentally ill family member, which can be legitimately considered as a chronic stress factor that reduces the overall resistance of the family members [11]. nine0007

A special comparison of the physical health of mothers and fathers of sick children [62] showed that the somatic health of fathers is better than that of mothers. In another comparative study [17], 31% of fathers with schizophrenia rated their physical health as unsatisfactory, compared with 6% of fathers whose children did not have mental illness. In addition to somatic pathology, relatives and caregivers of patients with schizophrenia were also found to have an increased frequency of infectious diseases, which was predicted by the severity of positive symptoms in a mentally ill family member, which can be legitimately considered as a chronic stress factor that reduces the overall resistance of the family members [11]. nine0007

Association of socio-demographic and clinical indicators with the severity of family burden

The severity, or severity, of the family burden of relatives of patients with schizophrenia is associated with a large number of interindividual differences and significant variable signs of both the relatives themselves and patients and is a complex multidimensional phenomenon [11]. To date, numerous factors that influence the severity of the family burden of relatives of patients have been described and studied. nine0007

To date, numerous factors that influence the severity of the family burden of relatives of patients have been described and studied. nine0007

The leading ones include traditional socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as the difference in the volume and quality of medical and social assistance provided to relatives.

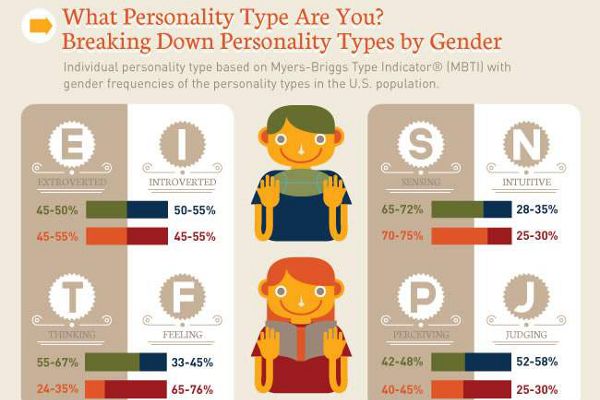

A number of studies [1, 6, 25, 26, 43, 47, 50, 82], concerning the relationship of socio-demographic indicators of patients with schizophrenia and their relatives with the severity of family burden, clearly showed that the male sex and younger age of patients with schizophrenia, as well as the female gender and older age of their relatives have a significant impact on the severity of the family burden. In addition, the family burden, as expected, turned out to be more pronounced in relatives with a lower educational level, lack of work, financial difficulties and lack of social support [6, 25, 32]. Thus, if we theoretically assess the severity of the family burden of relatives of patients with schizophrenia, using only socio-demographic characteristics, then its severity will be highest in families where a young man or young man with schizophrenia lives and his mother, who does not have a higher education, and also does not enjoy the social support of the state. In this typical description of the composition of the family with the heaviest family burden, it is the mother of the patient, and not his other close female relative, since almost all studies have obtained similar data, indicating that it is in the parents of patients with schizophrenia that the burden is most pronounced [26, 37]. Additional socio-demographic features that aggravate the family burden of relatives and are confirmed by the results of all studies [6, 56] are the lack of work of the patient himself and the presence of his marital status. nine0007

In this typical description of the composition of the family with the heaviest family burden, it is the mother of the patient, and not his other close female relative, since almost all studies have obtained similar data, indicating that it is in the parents of patients with schizophrenia that the burden is most pronounced [26, 37]. Additional socio-demographic features that aggravate the family burden of relatives and are confirmed by the results of all studies [6, 56] are the lack of work of the patient himself and the presence of his marital status. nine0007

The list of clinical factors affecting the severity of family burden includes traditional clinical and anamnestic characteristics of the course of schizophrenia: the presence and severity of various symptoms of psychosis and its duration, the number and duration of hospitalization in psychiatric hospitals [10, 28, 30, 77]. The study of the relationship between the total duration of the disease, the number of hospitalizations, and the high frequency of relapses of schizophrenia revealed a significant direct dependence of the severity of the family burden on the listed characteristics of the course of psychosis [22, 25, 34]. nine0007

nine0007

The study of the relationship between the presence and severity of positive and negative symptoms in patients and indicators of family pregnancy of relatives gave conflicting results. On the one hand, a number of studies [25, 49, 56, 72] have established a significant relationship between the severity of both positive and negative symptoms and the severity of family burden. On the other hand, A. Schene et al. [59] did not confirm the effect of positive and/or negative symptoms on manifestations of a heavier family burden, but found an association between individual symptoms of schizophrenia, such as apathy, and some indicators of the burden of relatives of patients. Some studies [11, 12, 53] have found a greater impact of negative symptoms of psychosis on measures of family burden. At the same time, the results of other studies [18, 39, 47, 64] indicate a significant impact on the severity of family burden only positive symptoms of schizophrenia and disorganized behavior of patients under the influence of psychotic disorders [37, 79].

These data suggest that the impact of certain mental disorders on the family burden of their relatives is associated with the action of other significant factors. This assumption is confirmed, in particular, by a study of 60 patients with schizophrenia and their relatives, performed by L. Raj et al. [54]. At the beginning of this study, there was no relationship between the presence of positive symptoms and the severity of the social burden of relatives, but after 6 months of follow-up, a significant relationship was found between the degree of reduction in positive symptoms and the social burden of the family. An opposite time relationship was found in this study between social burden and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. In addition, a natural factor explaining the lack of a direct and clear relationship between the severity and presence of positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia and indicators of family burden is the individual response of a particular relative to various manifestations of the disease [2]. nine0007

nine0007

Only a few studies have been devoted to the study of the relationship between the level of family burden of relatives and the cognitive deficit of patients. In a study by F. Hjarthag et al. [29] found a direct relationship between the severity of family burden and such parameters of patients' cognitive functioning as working memory and executive functions. In the well-known CATIE study [50], which included, in particular, the study of 623 caregivers (relatives or friends who provide direct care) of patients with schizophrenia, no significant relationship was found between the neurocognitive functioning of patients and family burden. Within the framework of the same study [51], for the first time, an attempt was made to study the effect of antipsychotic therapy received by patients with schizophrenia on the severity of family burden and no significant relationship was found between indicators of family burden and whether the antipsychotic received by patients belongs to the first (classical antipsychotics) or the second ( atypical antipsychotics) to their generation. nine0007

nine0007

The relationship between the volume of medical and social assistance to relatives of patients and the severity of family burden

The question of the impact of various forms of medical and social assistance on family burden is of a kind of historical significance, since it was precisely to study this problem that J. Grad and P. Sainsbury [20, 21] carried out their pioneering work, laying the foundation for studying the problem of family burden, first in England and the USA, and then in other countries. The relevance of studying the problem of providing medical and social assistance to relatives of patients with schizophrenia is due to the fact that it is often ignored or remains much weaker than, for example, assistance to relatives of patients with somatic pathology, despite the established relationship between the severity of the family burden of relatives of patients with schizophrenia and the degree of their satisfaction with medical and social care [41, 67]. Providing adequate professional support to relatives of mental patients significantly reduces the severity of various indicators of family burden [55], especially since the family of a patient with schizophrenia is considered the cornerstone of community care [63, 71]. nine0007

Providing adequate professional support to relatives of mental patients significantly reduces the severity of various indicators of family burden [55], especially since the family of a patient with schizophrenia is considered the cornerstone of community care [63, 71]. nine0007

It is obvious that the satisfaction of relatives with various forms of medical and social support includes both interindividual differences and common, typical for relatives of all mentally ill patients, the need to receive specialized assistance. Satisfaction with the specialized care received by its consumers is, according to modern concepts, a reflection of its quality and effectiveness [58]. The aggregated data shows that ⅔ relatives of patients with schizophrenia are satisfied with the volume and quality of professional assistance provided to them, and ⅓ — not satisfied [3, 66]. There is a positive correlation between the satisfaction of relatives with the medical and social assistance provided and such factors as parental status, the time elapsed since the onset of the disease, and the age of the patient by this time [24]. In a study by R. Tessler et al. [66] found that relatives of patients receiving medical and social assistance were most satisfied with the quality and volume of professional assistance received from psychologists, and further, in terms of decreasing satisfaction, from nurses, social workers, and psychiatrists. nine0007

In a study by R. Tessler et al. [66] found that relatives of patients receiving medical and social assistance were most satisfied with the quality and volume of professional assistance received from psychologists, and further, in terms of decreasing satisfaction, from nurses, social workers, and psychiatrists. nine0007

The dissatisfaction of relatives of patients with schizophrenia with professional help, which affects the severity of family burden, is due to their typical unmet needs, which include receiving practical assistance in caring for the sick and receiving various types of social support, receiving feasible practical advice, access to obtaining understandable information necessary volume on the prognosis and causes of the disease, increasing the effectiveness of therapy, having more frequent contacts with representatives of medical and social services [9, 15, 36, 75, 80]. It has been established that the need to provide various forms of medical and social assistance to relatives increases significantly in parallel with an increase in the duration of the disease and the number of hospitalizations of patients [81].

Satisfaction with the performance of outpatient psychiatric institutions by relatives of patients is directly related to the degree of satisfaction with outpatient professional services and the patients themselves. Regarding patients with schizophrenia, it is known that they have a fairly high number of unmet needs in obtaining certain types of medical and social assistance [42]. Of course, the high number of unmet needs of patients with schizophrenia is an independent problem, but also a factor that can have a negative impact on the subjective and objective indicators of the family burden of their relatives. nine0007

Summarizing the above, we can conclude that the study of the family burden of relatives of the mentally ill is an actual area of research related to the psychological well-being and mental health of a contingent of people living under conditions of chronic stress for a long time, and in some cases for a lifetime. Relatives of the mentally ill are significantly influenced by numerous adverse factors, the role and significance of which have not been fully studied. As an example, we can cite the inconsistency of the results obtained in the study of one of the key issues - the impact of positive and negative symptoms of a patient with schizophrenia on the presence and severity of the family burden of his relatives. Numerous adverse factors that affect relatives of patients with schizophrenia affect almost all areas of their life, as evidenced by a wide range of problems they experience in the areas of psychological, physical health, social and financial. As part of the problem of the family burden of relatives of patients with schizophrenia, the question of the extent to which the presence and severity of family burden and the psychological well-being of relatives is due to the peculiarities of their personal response and attitude to the mental illness of a family member, as well as the possible presence of various psychopathological disorders of the subclinical level. nine0007

As an example, we can cite the inconsistency of the results obtained in the study of one of the key issues - the impact of positive and negative symptoms of a patient with schizophrenia on the presence and severity of the family burden of his relatives. Numerous adverse factors that affect relatives of patients with schizophrenia affect almost all areas of their life, as evidenced by a wide range of problems they experience in the areas of psychological, physical health, social and financial. As part of the problem of the family burden of relatives of patients with schizophrenia, the question of the extent to which the presence and severity of family burden and the psychological well-being of relatives is due to the peculiarities of their personal response and attitude to the mental illness of a family member, as well as the possible presence of various psychopathological disorders of the subclinical level. nine0007

At the same time, studies of the family burden of relatives of patients with schizophrenia have already provided a number of important facts.