Overcoming mental illness naturally

Ten Things You Can Do for Your Mental Health

Try these tips to keep your balance, or re-balance yourself.*

1. Value yourself:

Treat yourself with kindness and respect, and avoid self-criticism. Make time for your hobbies and favorite projects, or broaden your horizons. Do a daily crossword puzzle, plant a garden, take dance lessons, learn to play an instrument or become fluent in another language.

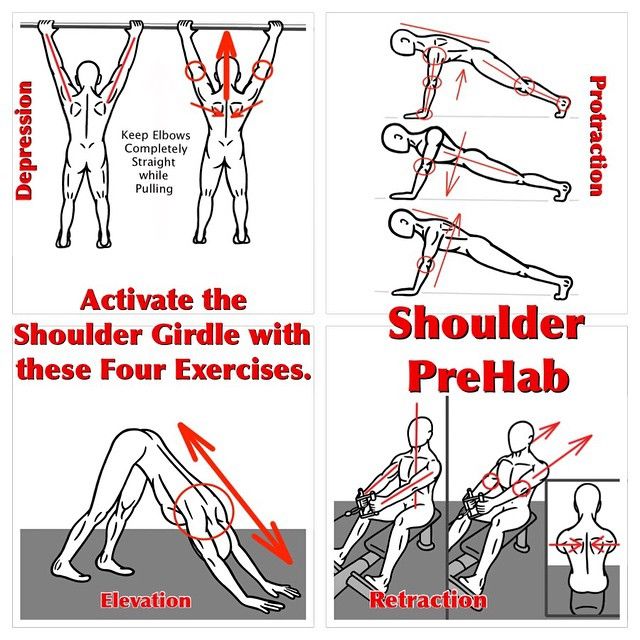

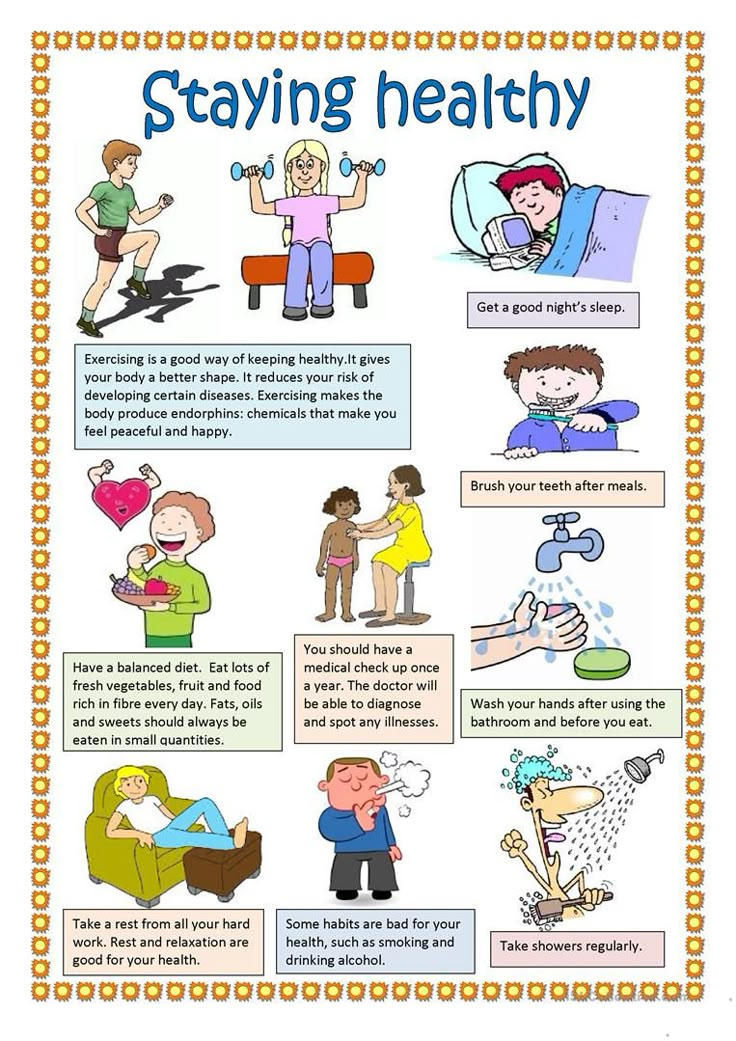

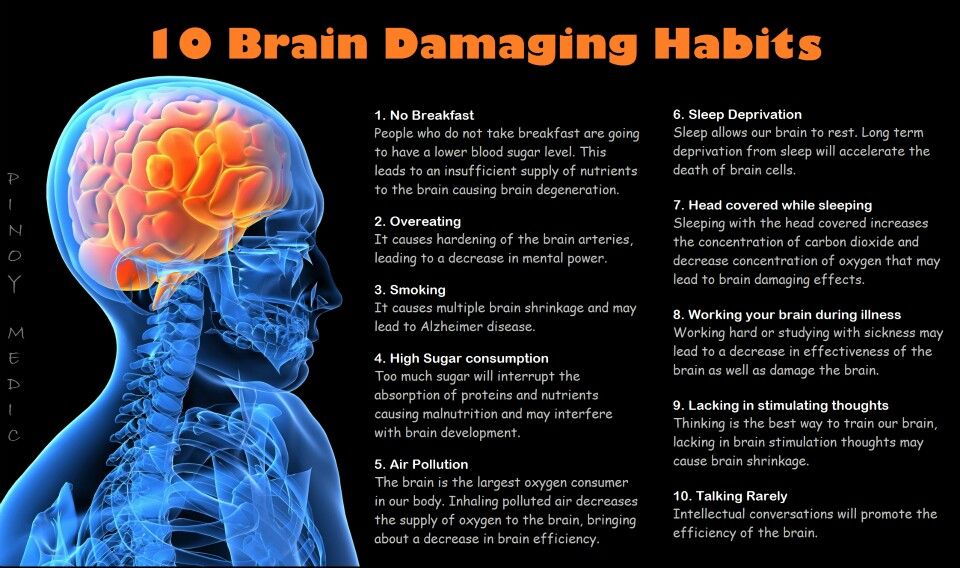

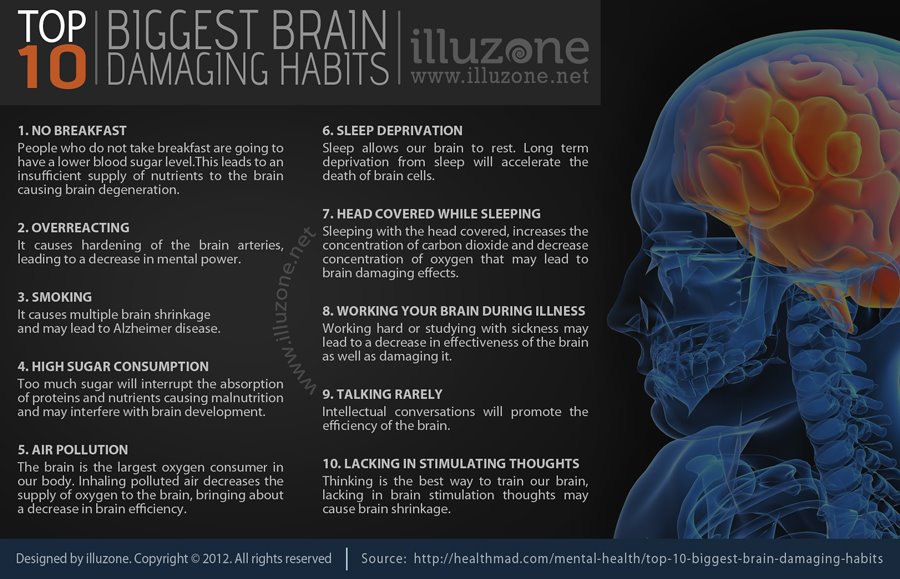

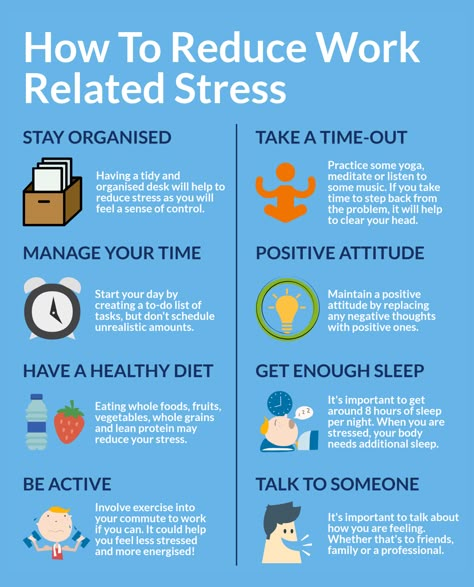

2. Take care of your body:

Taking care of yourself physically can improve your mental health. Be sure to:

- Eat nutritious meals

- Avoid smoking and vaping-- see Cessation Help

- Drink plenty of water

- Exercise, which helps decrease depression and anxiety and improve moods

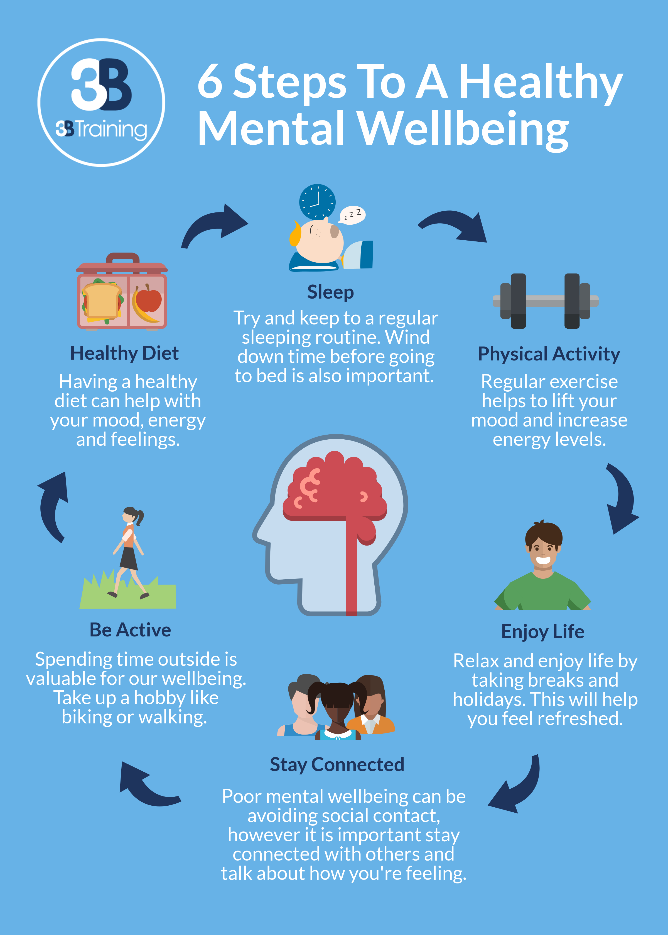

- Get enough sleep. Researchers believe that lack of sleep contributes to a high rate of depression in college students.

3. Surround yourself with good people:

People with strong family or social connections are generally healthier than those who lack a support network. Make plans with supportive family members and friends, or seek out activities where you can meet new people, such as a club, class or support group.

4. Give yourself:

Volunteer your time and energy to help someone else. You'll feel good about doing something tangible to help someone in need — and it's a great way to meet new people. See Fun and Cheap Things to do in Ann Arbor for ideas.

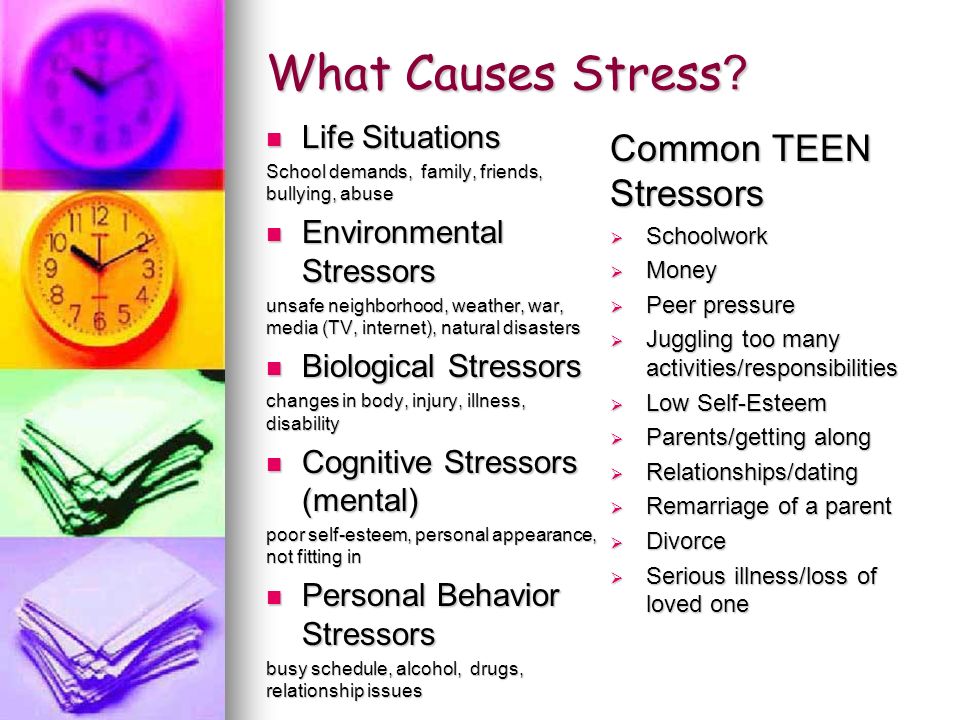

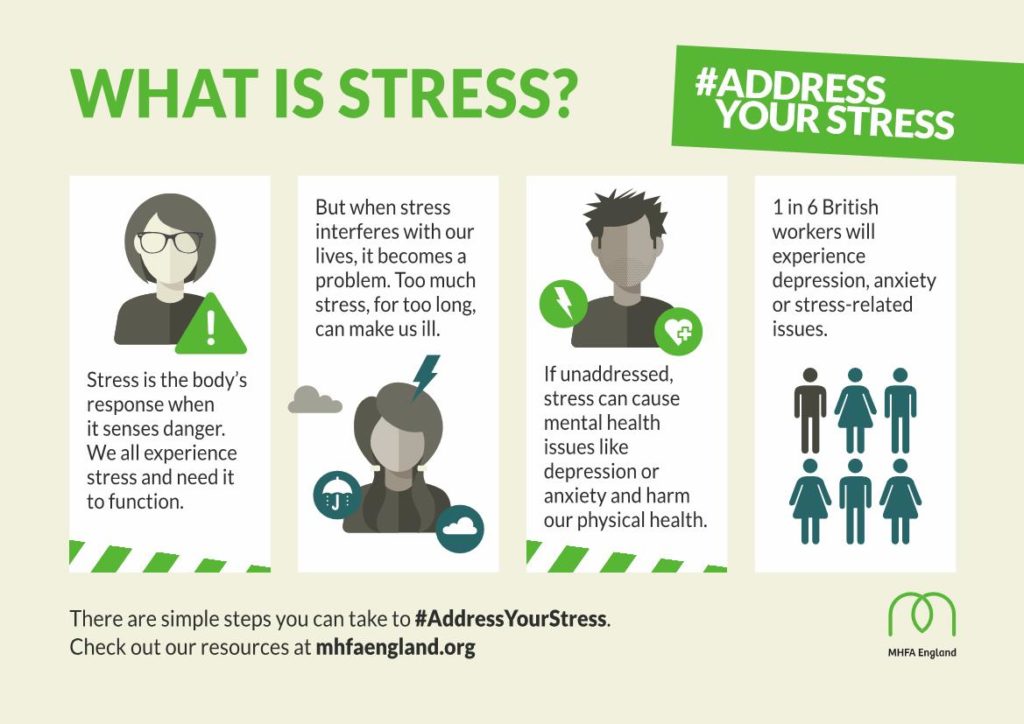

5. Learn how to deal with stress:

Like it or not, stress is a part of life. Practice good coping skills: Try One-Minute Stress Strategies, do Tai Chi, exercise, take a nature walk, play with your pet or try journal writing as a stress reducer. Also, remember to smile and see the humor in life. Research shows that laughter can boost your immune system, ease pain, relax your body and reduce stress.

6. Quiet your mind:

Try meditating, Mindfulness and/or prayer. Relaxation exercises and prayer can improve your state of mind and outlook on life. In fact, research shows that meditation may help you feel calm and enhance the effects of therapy. To get connected, see spiritual resources on Personal Well-being for Students

To get connected, see spiritual resources on Personal Well-being for Students

7. Set realistic goals:

Decide what you want to achieve academically, professionally and personally, and write down the steps you need to realize your goals. Aim high, but be realistic and don't over-schedule. You'll enjoy a tremendous sense of accomplishment and self-worth as you progress toward your goal. Wellness Coaching, free to U-M students, can help you develop goals and stay on track.

8. Break up the monotony:

Although our routines make us more efficient and enhance our feelings of security and safety, a little change of pace can perk up a tedious schedule. Alter your jogging route, plan a road-trip, take a walk in a different park, hang some new pictures or try a new restaurant. See Rejuvenation 101 for more ideas.

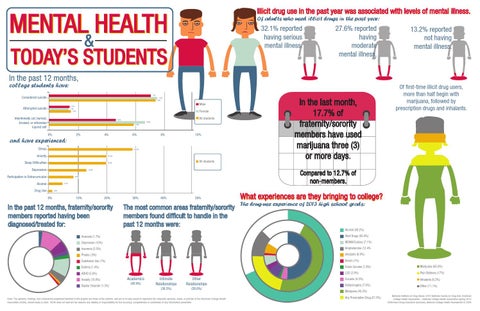

9. Avoid alcohol and other drugs:

Keep alcohol use to a minimum and avoid other drugs. Sometimes people use alcohol and other drugs to "self-medicate" but in reality, alcohol and other drugs only aggravate problems. For more information, see Alcohol and Other Drugs.

For more information, see Alcohol and Other Drugs.

10. Get help when you need it:

Seeking help is a sign of strength — not a weakness. And it is important to remember that treatment is effective. People who get appropriate care can recover from mental illness and addiction and lead full, rewarding lives. See Resources for Stress and Mental Health for campus and community resources.

*Adapted from the National Mental Health Association/National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare

7 Natural Ways to Help Manage Depression and Your Overall Mental Health

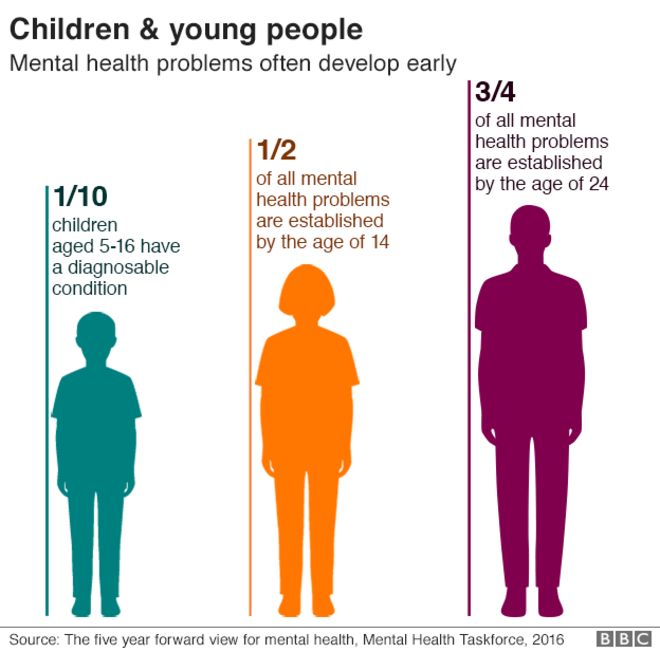

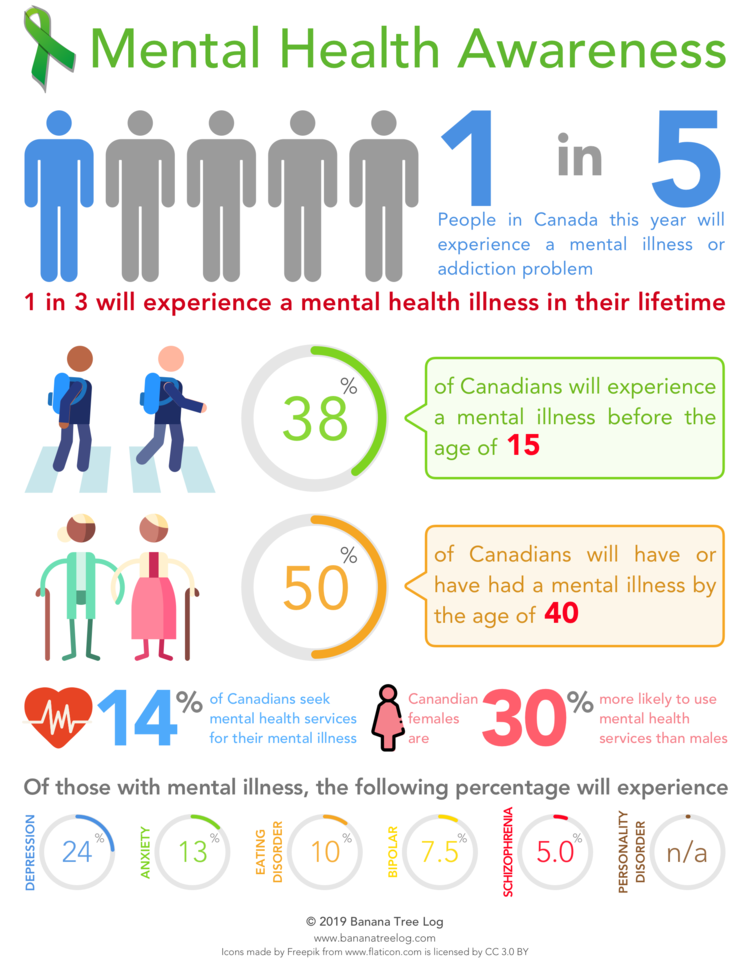

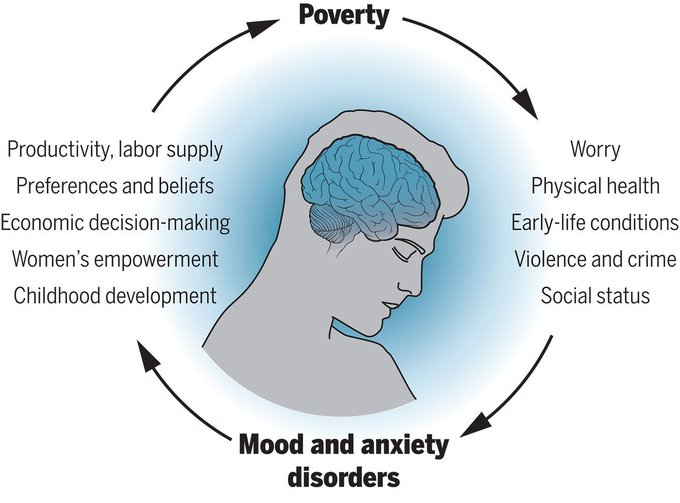

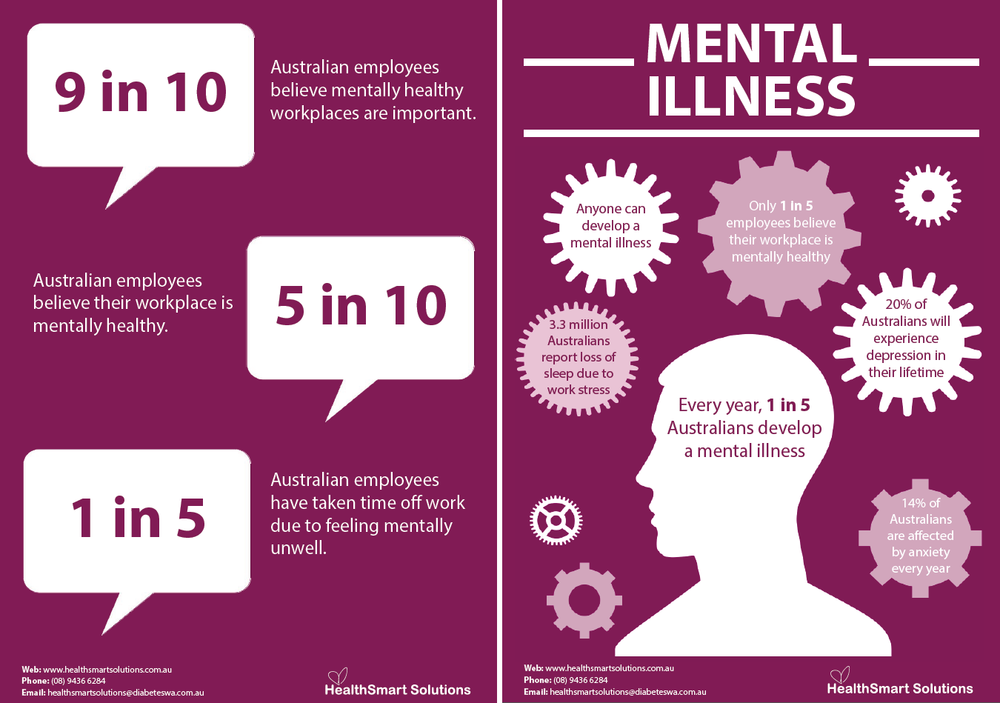

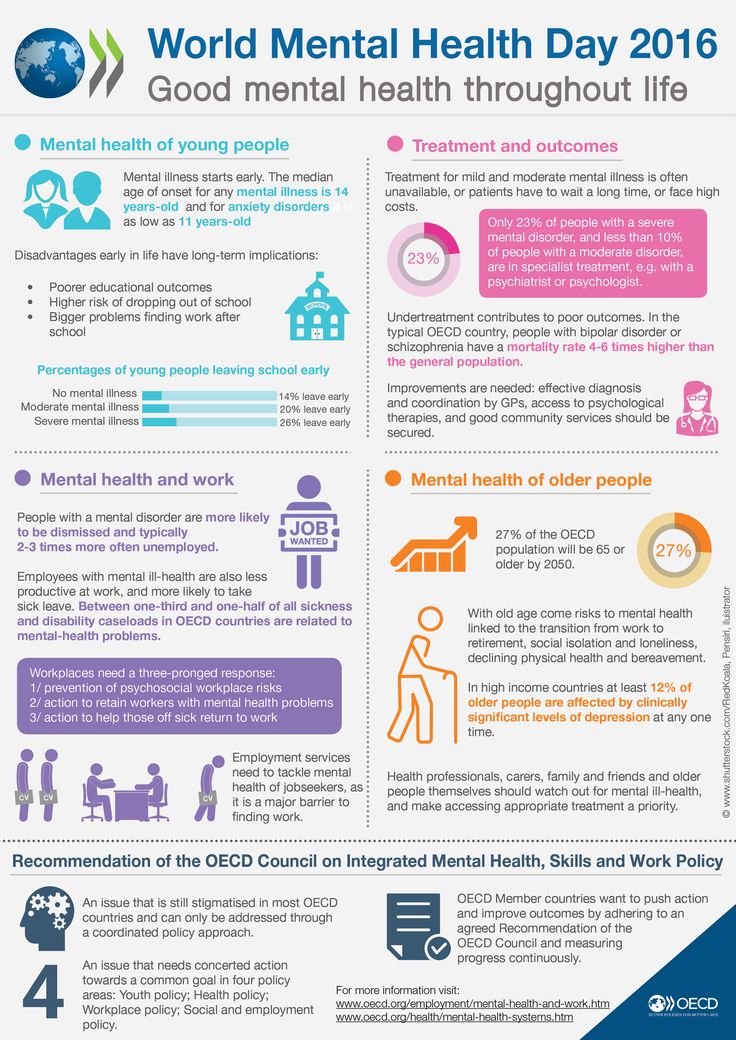

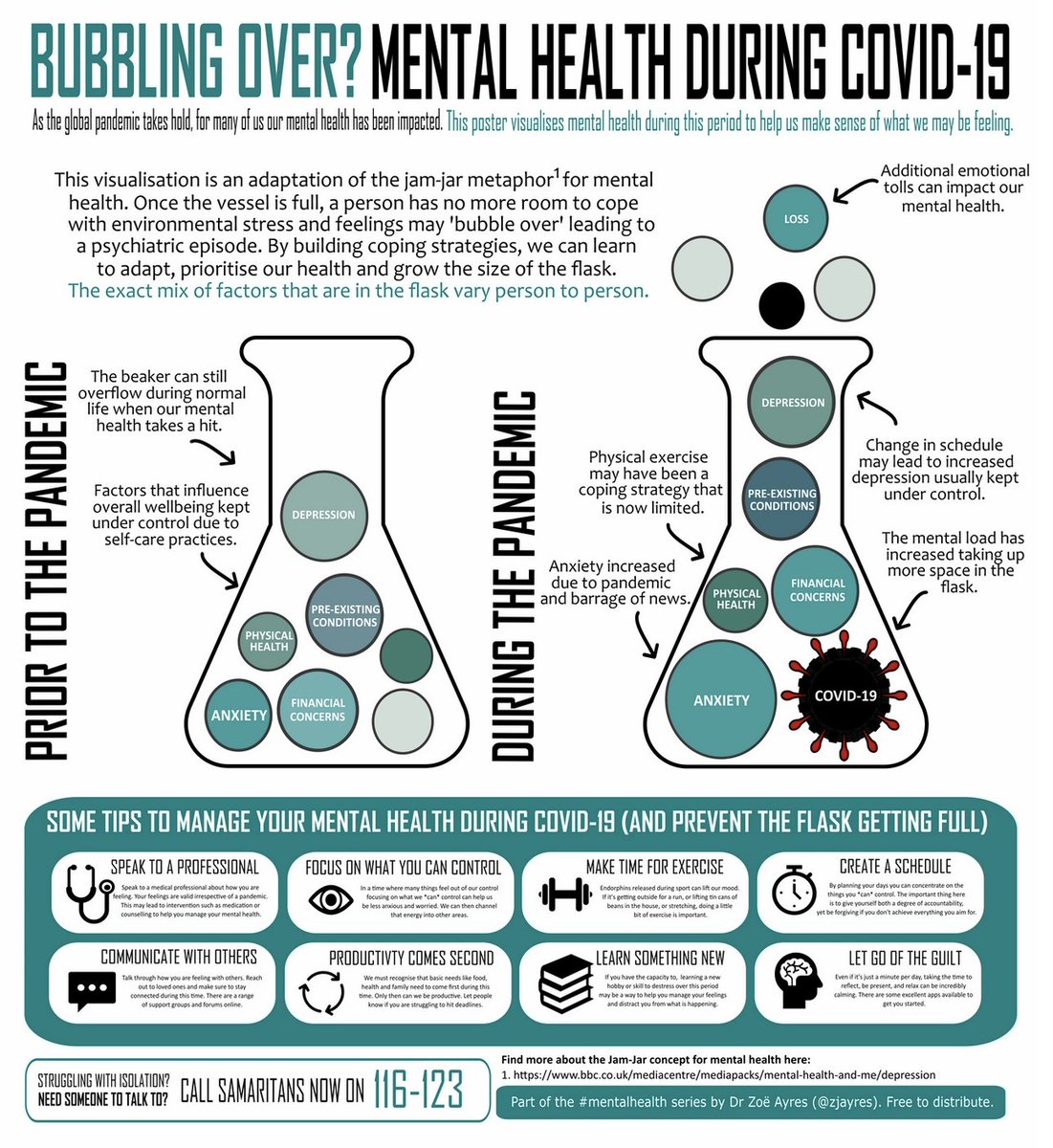

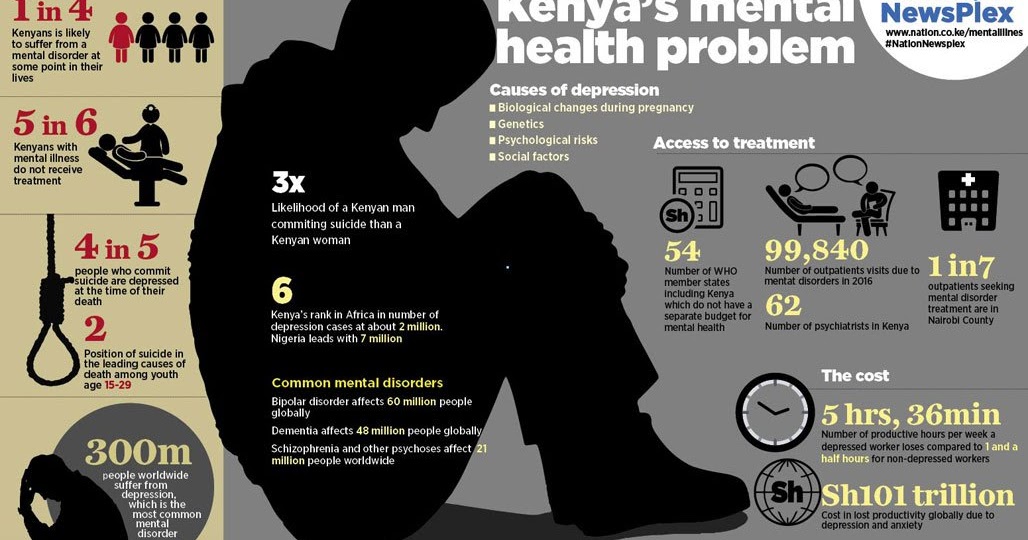

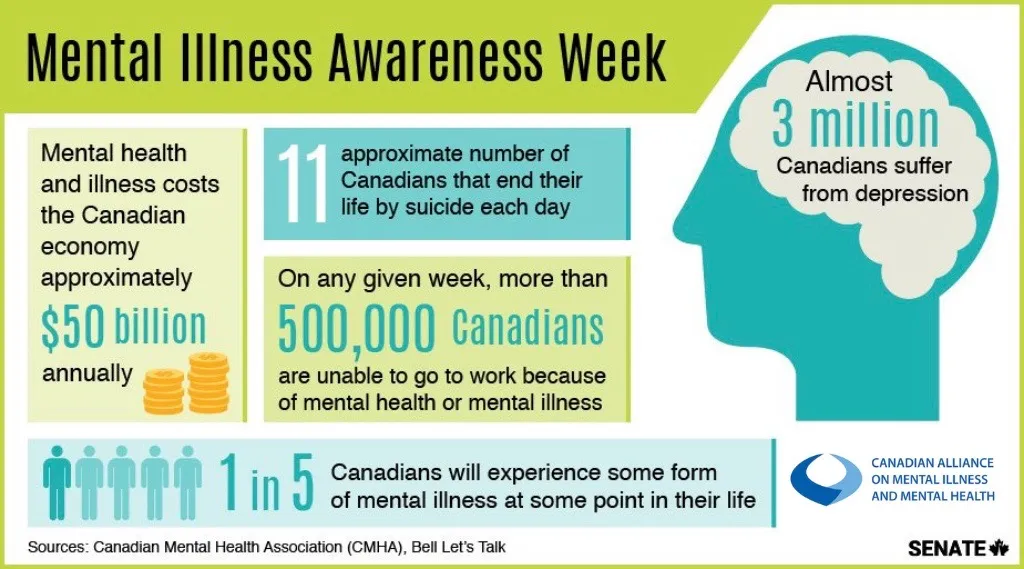

According to a report by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), antidepressant use has risen by 65% between 1999 and 2014. A 2017 study also shows depression increased “significantly” among persons in the U.S. from 2005 to 2015, from 6.6% to 7.3%.

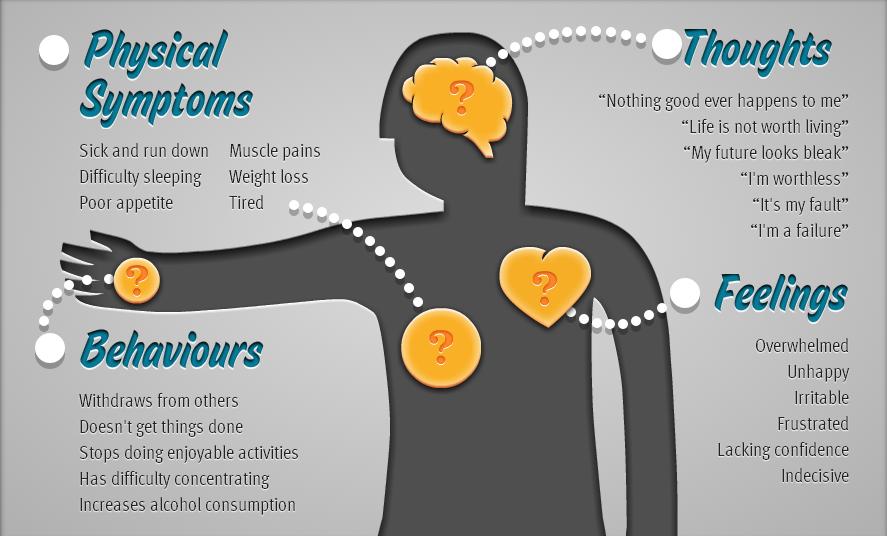

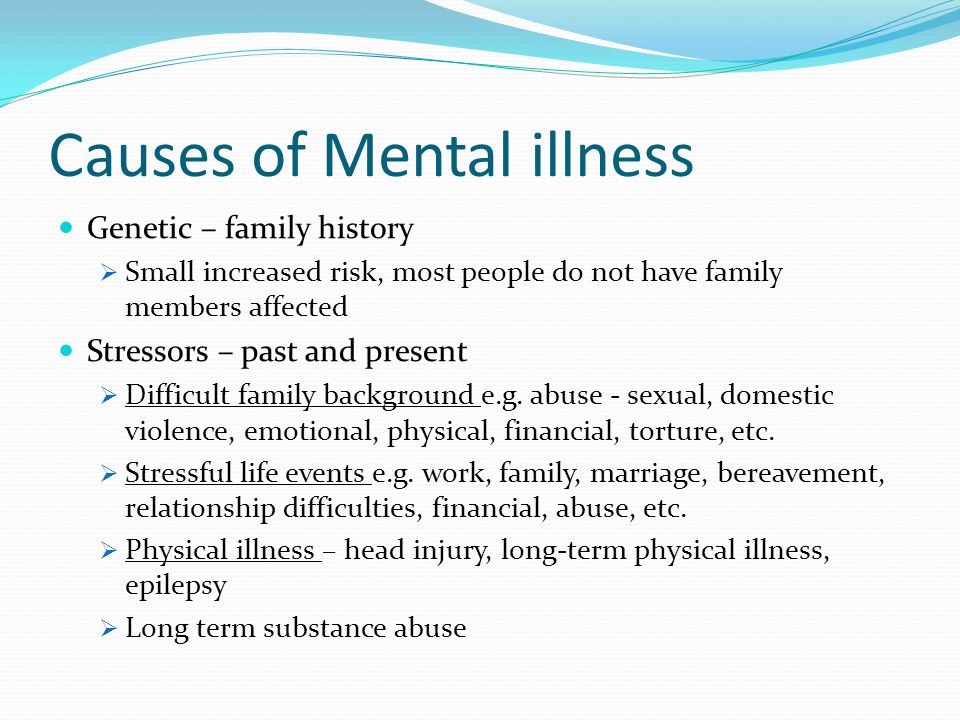

Research tells us that one of the biggest triggers for depression is chronic stress both from physical health issues such as chronic pain and psychosocial issues. So it is no surprise that with the economic and social stressors during the last 10 years that rates of depression would be on the rise.

So it is no surprise that with the economic and social stressors during the last 10 years that rates of depression would be on the rise.

Alongside pharmaceuticals, utilizing various types of treatment modalities including complementary and alternative medicine techniques often can lead to better outcomes than single modality interventions. These techniques may also help those who might want to rely less on pharmaceuticals in the long term.

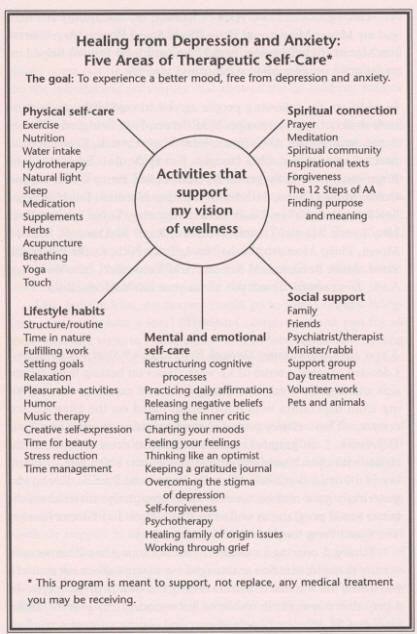

Some natural treatment modalities include:

1. Botanicals to treat depression

In addition to helpful lifestyle and diet changes, naturopathic doctors specialize in using botanical and other herbal supplements to treat various ailments including depression. Specifically, certain herbs have been shown to be effective in the management and treatment of depression.

For example, an analysis of 29 studies shows that using St. John’s Wort extract was similarly as effective as standard antidepressants, but with fewer side effects. Kava Kava extract has also been shown to ease depression symptoms like anxiety. Patients should always be sure to discuss the use of botanicals with prescription medications with their doctor, since there is always the possibility of dangerous interactions with specific combinations.

Kava Kava extract has also been shown to ease depression symptoms like anxiety. Patients should always be sure to discuss the use of botanicals with prescription medications with their doctor, since there is always the possibility of dangerous interactions with specific combinations.

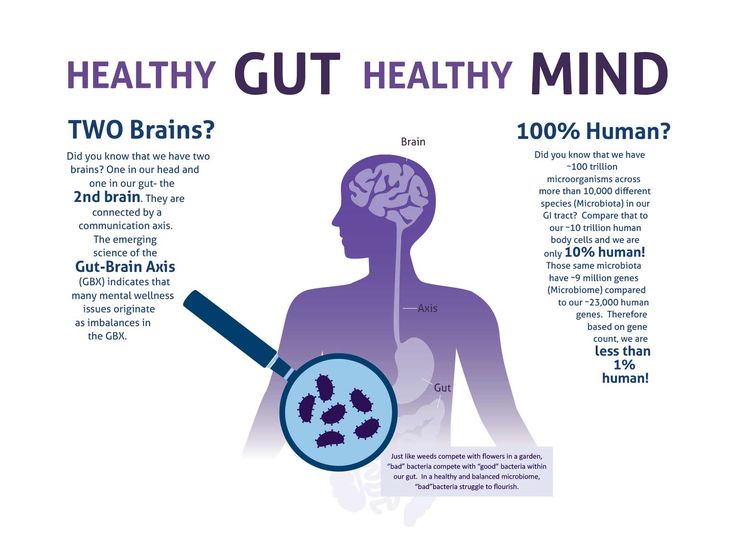

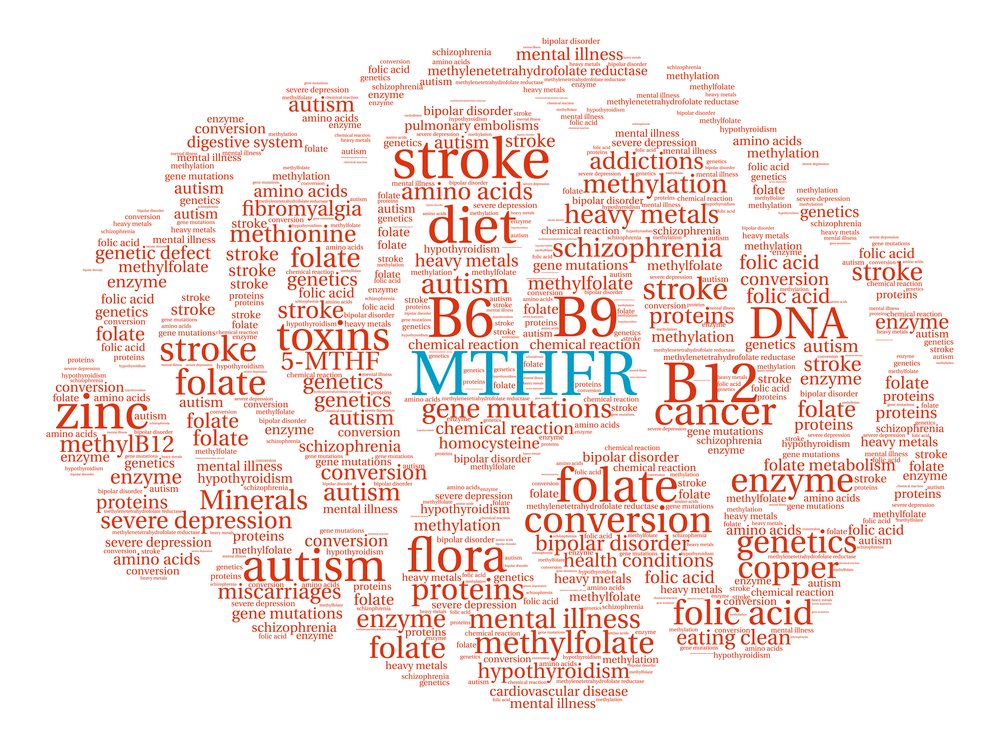

2. Proper diet and nutrition to help anxiety

Modifying what you eat can have profound effects on both your overall health and mental health. A healthy diet, in particular, can help regulate anxiety levels, according to recent research. Experts recommend that individuals with depression avoid overconsumption of sugary and processed foods along with caffeine and alcohol.

Additionally, more doctors are recognizing the role that bacteria in your gut can have on mental health. A healthy diet that includes probiotic-rich foods like yogurt and kefir can help promote a proper balance of gut bacteria. Taking pre and probiotic supplements may be beneficial as well.

3. Massage therapy to manage mental health

By decreasing heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen consumption and salivary cortisol levels, massage therapy helps reduce both stress and anxiety, two major contributors to depression.

You don’t need an hour-long massage to achieve these benefits either. Multiple controlled studies found that these physiological and psychological changes occurred after 10 to 15 minute chair massages. So no matter how busy your schedule is, you can easily make time for this de-stressing method. For enhanced relaxation, massage therapy can also be combined with aromatherapy.

4. Meditation to center yourself

Meditation is a relaxation technique that has been used for many years. If practiced for as little as 10 minutes a day, it can be an excellent way to combat mental health issues. According to a 2014 study by Johns Hopkins University meditation can improve psychological stresses such as anxiety, depression, and pain. It’s no surprise that mediation is becoming more popular among the public as well as health care professionals.

There are various types of meditation techniques, allowing you to choose the most effective to relieve stress:

- Guided - patients form mental images of places of things that they find relaxing.

- Mindfulness - patients learn to have an increased awareness and acceptance of living in the present moment.

- Transcendental - this requires less concentration. People repeat a personally assigned mantra, such as a word, sound or phrase, in a specific way.

5. Acupuncture to improve well-being

Research has proven that acupuncture can improve a person’s well-being by stimulating the body’s healing processes. According to one study, those suffering from depression may benefit from acupuncture just as much as they do from counseling. In the study, one in three patients who used acupuncture for three months was no longer depressed.

6. Exercise to improve mood

Exercising pumps up endorphins and raises brain activity allowing you to take your mind off things and improve your overall mood. Any type of exercise, whether it is aerobics, Pilates, or weight training can help alleviate depression symptoms significantly. Find an activity that you enjoy and stick with it! Exercising on a daily basis will allow you to take your stress out on something in a positive way.

7. Sleep to reduce depression

For a long time sleep disturbance has been identified as a symptom of depression. In recent years research has shown that a sleep pattern of too little or too much sleep is a risk factor for depression. Health recommendations are for 7-9 hours of sleep per night with increased health risks outside that range. Currently, only 59% of U.S. adults meet that standard with four in 10 Americans getting less than the recommended amount of nightly sleep. Changing lifestyle and sleep habits can reduce your risk of depression, according to research.

Depression is a complex issue that everyone experiences differently. According to a 2014 study in BMC Psychiatry, there is compelling evidence that a range of lifestyle factors are involved with depression. Because of this, treating depression requires the individualized approach many complementary and alternative medicine practitioners offer.

Much of the recent research on depression looks at the changes in brain function associated with depression and how different treatments (both pharmaceuticals and holistic) can impact brain function. That research also shows us that depression may not be a single entity, that there are several distinct pathological brain patterns in people who are depressed.

That research also shows us that depression may not be a single entity, that there are several distinct pathological brain patterns in people who are depressed.

We invite you to learn about other ways you can improve your overall health and well-being by subscribing to our blog — The Future of Integrative Health.

PHARMATEKA » Overcoming non-compliance in the treatment of chronic mental illness

The article deals with the complex problems of non-compliance in the treatment of chronic mental illness with an emphasis on patient motivation and behavioral aspects. A continuum of behavioral models of adherence to therapy is presented - from complete refusal to abuse. Recommendations are given for overcoming noncopliance in the process of motivational therapy.

Keywords: motivational therapy, chronic mental illness, non-compliance, compliance

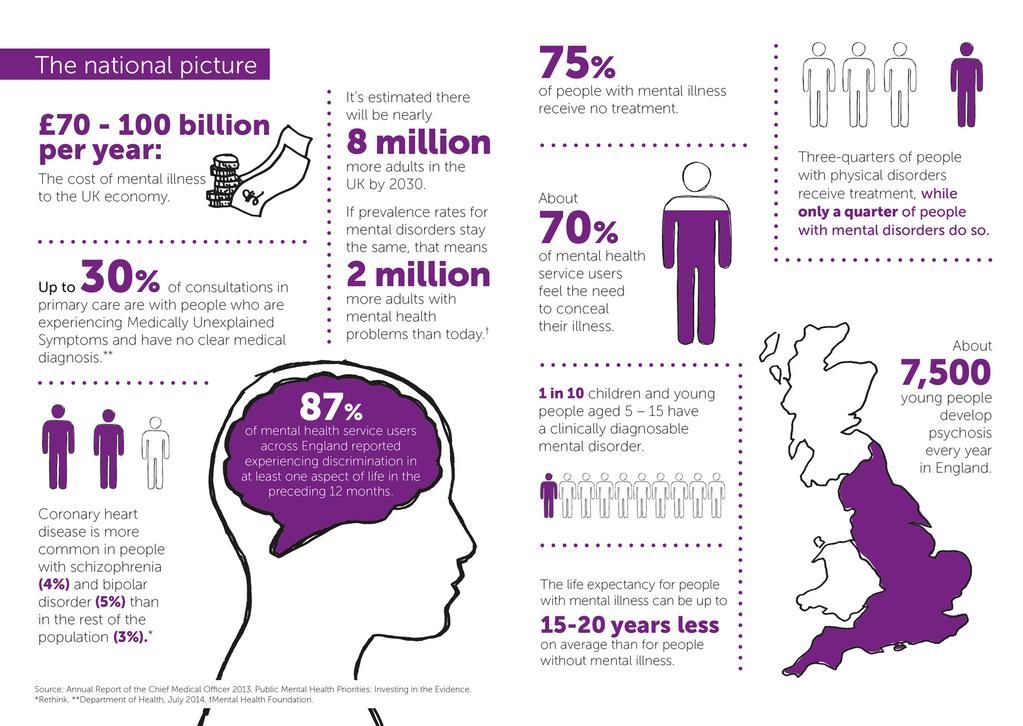

The problem of compliance (consent, cooperation) is currently attracting great attention both in general somatic medicine and in psychiatry. This is due to the need for long-term therapy of most somatic (diabetes, hypertension, etc.), as well as mental diseases, primarily in order to prevent possible exacerbations and relapses. The prevalence of non-compliance (NC, disagreement) is exceptionally high. Thus, in chronic somatic diseases it is 30–60% [1], and in mental diseases it reaches 70–80% [2, 3].

This is due to the need for long-term therapy of most somatic (diabetes, hypertension, etc.), as well as mental diseases, primarily in order to prevent possible exacerbations and relapses. The prevalence of non-compliance (NC, disagreement) is exceptionally high. Thus, in chronic somatic diseases it is 30–60% [1], and in mental diseases it reaches 70–80% [2, 3].

In the study of A.B. Cerkoney, K. Hart [4, 5] showed that only 7% of patients with insulin-dependent diabetes perform all the steps necessary to control the disease. It is no coincidence that NK in severe somatic diseases is regarded as passive suicide (reducing the dose of the drug or changing the mode of its administration) or active incomplete suicide (complete refusal of treatment) [6].

At the same time, great difficulties arise with the qualification and assessment of NDT as such [7]. So, according to DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders)-IV (1994), the category of disagreement with treatment can be used only when the focus of clinical attention is disagreement with important aspects of the treatment of the disease or the general condition of the patient. Thus, we are not talking about all aspects of therapy, but only about important ones. Moreover, the statement of "importance" is given at the mercy of the doctor, which should lead to frequent discrepancies in the points of view of the participants in the therapeutic process and in itself can lead to NK.

Thus, we are not talking about all aspects of therapy, but only about important ones. Moreover, the statement of "importance" is given at the mercy of the doctor, which should lead to frequent discrepancies in the points of view of the participants in the therapeutic process and in itself can lead to NK.

Completely different is the definition of compliance as the degree to which the patient's behavior is consistent with medical requirements: passively or actively (in the latter case, an alternative to compliance and a more neutral term "adherence" - adherence, or "concordance") is proposed. Such an understanding of compliance is adequate to the definition of NC as any deviation from prescribed medical recommendations (including reducing the number of drugs taken or their dose, changing the time of taking pills, etc.) and is more consistent with the well-known in our country definition of “reception mode” drug therapy. However, there is some difference between agreeing to treatment and following medical advice. The first is connected with the subjective attitude of the patient to therapy, with the degree of conformity of his ideas about the therapeutic process with the ideas of the doctor; the second refers to the behavioral aspect of the patient's functioning. The possible discrepancy between the results is obvious. There is another definition of compliance, which implies a certain internal space of the patient, within which we can talk about the coincidence of the patient's actions with medical recommendations. In this sense, it is believed that the degree of compliance also reflects the degree of patient satisfaction with the quality of medical care. However, this is not entirely true, since there are often clearly overestimated requirements of patients for the quality of medical care, based on the patient's naive hopes for a quick cure that are divorced from reality and naive. In addition, compliance with therapy, which depends on an extremely large number of factors, is highly unstable. Thus, loss of trust in a doctor, or iatrogenesis, can change compliance to NC in one day, which indicates the subjective significance of a certain factor at a certain point in therapy.

The first is connected with the subjective attitude of the patient to therapy, with the degree of conformity of his ideas about the therapeutic process with the ideas of the doctor; the second refers to the behavioral aspect of the patient's functioning. The possible discrepancy between the results is obvious. There is another definition of compliance, which implies a certain internal space of the patient, within which we can talk about the coincidence of the patient's actions with medical recommendations. In this sense, it is believed that the degree of compliance also reflects the degree of patient satisfaction with the quality of medical care. However, this is not entirely true, since there are often clearly overestimated requirements of patients for the quality of medical care, based on the patient's naive hopes for a quick cure that are divorced from reality and naive. In addition, compliance with therapy, which depends on an extremely large number of factors, is highly unstable. Thus, loss of trust in a doctor, or iatrogenesis, can change compliance to NC in one day, which indicates the subjective significance of a certain factor at a certain point in therapy.

No less controversial are the conceptual models of compliance, reflecting the variety of research approaches to the study of this problem: 1) a biomedical model with a focus on aspects such as treatment regimen and side effects; 2) a behavioral model with an emphasis on environmental influences and the development of behavioral skills; 3) an educational model focused on improving the relationship between the patient and the doctor; 4) a model of popular ideas about health in society, based primarily on a rational assessment of utility, as well as barriers to treatment; 5) a model of self-regulating systems, within which cognitive and emotional reactions to the threat of a disease are analyzed. An analysis of these compliance models shows that some of them are based on a belief in recovery, others on alternative adaptation, others on cognitive functions, etc. The lack of any comparability between them, as well as a unified theory of compliance development, causes reasonable criticism from opponents of both these models themselves and the results obtained by using them [5].

Contradictions in the definition of the term "compliance" and models of its development are supplemented by the actual absence of full-fledged standardized methods for assessing patient disagreement with therapy. Wide discrepancies regarding the level of compliance of patients with somatic and mental disorders are partly explained by incomparable methods of its assessment (qualitative and quantitative; subjective and objective; direct and indirect), the duration of the observation period, as well as the criteria for the NC itself (any or only unacceptable deviation from the recommended drug regimen). Methods such as questioning the patient, counting the drug remaining after taking it, microelectronic monitoring (MEMS - Medication Event Monitoring System), which allows you to register how many times during the day patients open packages of pills, are usually not reliable enough and cannot give a guaranteed estimate for the fact that patients are taking medications. Thus, during interviews, patients often give false information, simply hiding the real information from the doctor. Anamnestic information from the words of patients and their relatives often differs so much that it is almost impossible to interpret them. And these or those options for counting dosage forms, in spite of everything, leave too many opportunities for patients to manipulate their number. More reliable data can be obtained from pharmacokinetic studies with the determination of drug metabolites or other specific markers. However, these methods are too expensive and complex, which is why the vast majority of studies to assess patient compliance use less reliable approaches.

Anamnestic information from the words of patients and their relatives often differs so much that it is almost impossible to interpret them. And these or those options for counting dosage forms, in spite of everything, leave too many opportunities for patients to manipulate their number. More reliable data can be obtained from pharmacokinetic studies with the determination of drug metabolites or other specific markers. However, these methods are too expensive and complex, which is why the vast majority of studies to assess patient compliance use less reliable approaches.

From our point of view, full compliance is just the middle point on a wide continuum of the degree of adherence of patients to ongoing therapy (from complete or partial resistance to therapy to its abuse) and is rather a desired goal, while NC to treatment, i.e. anything less than full compliance has many different forms and needs to be carefully analyzed and studied. The terms “compliance” and “non-compliance”, despite their importance for clinical practice, are too broad and difficult to diagnose concepts, and therefore agreement / disagreement with treatment often act as subjective categories that are difficult to objectively analyze. At the same time, it should be noted that full compliance is often achieved by patients with certain disorders (for example, with hypochondriacal) or with certain attitudes (for example, with rent), which raises the question of its desirability.

At the same time, it should be noted that full compliance is often achieved by patients with certain disorders (for example, with hypochondriacal) or with certain attitudes (for example, with rent), which raises the question of its desirability.

In order to make this area accessible to direct assessment, and therefore to scientific research, it is necessary to first select from it the most delineated and measurable components. In this sense, refusal (a problematic term) of treatment can be considered as the most obvious or extreme form of NC, since it is an open (and conscious) expression of the patient's disagreement with the recommended treatment, accompanied by an appropriate behavioral response. Being an extreme variant of NC, refusal of therapy is an unambiguous resultant of the entire range of factors that cause it and is much easier to both primary diagnosis and comprehensive measurement (compared to the assessment of compliance in general). It includes refusal to visit a doctor or hospitalization, and refusal to start treatment or premature discontinuation of drugs, and their use without taking into account the recommendations received. Partial NK in this sense would mean a partial refusal of therapy. At the same time, patients usually refuse to take certain drugs or the necessary dosages of drugs. Hidden refusals, often masked by simple forgetfulness, occur either when the cognitive component of refusal of the recommended treatment is not fully developed in the patient's mind, or in the absence of obvious congruence between the emotional-cognitive and behavioral components of refusal.

Partial NK in this sense would mean a partial refusal of therapy. At the same time, patients usually refuse to take certain drugs or the necessary dosages of drugs. Hidden refusals, often masked by simple forgetfulness, occur either when the cognitive component of refusal of the recommended treatment is not fully developed in the patient's mind, or in the absence of obvious congruence between the emotional-cognitive and behavioral components of refusal.

In the above presentation, the assessment of NC is actually an assessment of refusal (complete or partial, primary / early or secondary / late, single / recurrent, competent / incompetent, overt / covert) from therapy (if we do not mean the simple forgetfulness of the patient), which can act as a central model for the study of NC in general. At the same time, it should be remembered that the patient's refusal of treatment always occurs within the framework of the doctor-patient contact and is largely determined by its qualitative characteristics. The influence of all other factors is also realized in the situation of this contact.

The influence of all other factors is also realized in the situation of this contact.

Thus, the doctor-patient relationship can be given the status of a backbone when considering the problem of patient refusals from therapy in a comprehensive manner. It must be added that the relationship between doctors and patients in the modern world is becoming more and more complex. This is facilitated by a huge number of new pharmacological agents thrown onto the market, and an insufficient degree of standardization of medical prescriptions, and an unprecedented variety of therapeutic requests of the population.

The transition from the concept of “non-compliance” to the concept of “refusal of therapy” in the framework of studying the problem of patient disagreement with treatment allows us to propose not only a differentiated typology of refusals and, on this basis, to identify their predictors, but also to propose methods for their correction and prevention.

If we talk about the factors that contribute to NC, then out of their almost limitless multitude, only a few are unambiguously negative. With more or less reservations, most clinicians consider discomfort caused by various adverse medical events as reasons for disagreeing with treatment; high cost of treatment; judgments of patients regarding the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed treatment, based on individual, religious or cultural values; adaptation difficulties due to personal characteristics (for example, denial of the disease), etc. On the other hand, such factors as full informing patients about the possible side effects of drugs prescribed by a doctor, a single dose of them, or, for example, the use of intramuscular injections by different patients, can contribute to both compliance, and NK.

With more or less reservations, most clinicians consider discomfort caused by various adverse medical events as reasons for disagreeing with treatment; high cost of treatment; judgments of patients regarding the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed treatment, based on individual, religious or cultural values; adaptation difficulties due to personal characteristics (for example, denial of the disease), etc. On the other hand, such factors as full informing patients about the possible side effects of drugs prescribed by a doctor, a single dose of them, or, for example, the use of intramuscular injections by different patients, can contribute to both compliance, and NK.

Side effects of drugs, according to some researchers, are one of the most significant reasons leading to refusal of therapy. However, according to our data, it is not so much the number and range of adverse events that matter for this, but their subjective intolerance: some of the side effects are so subjectively painful and difficult to tolerate that patients refuse the appropriate drugs, despite the fact that they generally understand the need for their use. . Particularly important in this case are side effects that outstrip the main therapeutic effect of the drug in their development. At the same time, it was noted that the more intelligent the patient, the greater the demands he makes to the therapy, especially in terms of minimizing side effects that negatively affect his everyday life and make it difficult to perform his usual social functions [8]. K. Demyttenaere [9] believes that side effects and other adverse events, including severe ones that occur during therapy, can be considered as predictors of only early, but not late, secondary refusals of treatment. Late and recurrent secondary withdrawals from treatment are usually associated with long-term treatment of resistant conditions. Many authors express the opinion that overly complex or frequently changing therapeutic regimens at the same time simply confuse patients, and the long-term absence of a positive effect “pushes” them to independently increase dosages and change the regimen of taking drugs.

. Particularly important in this case are side effects that outstrip the main therapeutic effect of the drug in their development. At the same time, it was noted that the more intelligent the patient, the greater the demands he makes to the therapy, especially in terms of minimizing side effects that negatively affect his everyday life and make it difficult to perform his usual social functions [8]. K. Demyttenaere [9] believes that side effects and other adverse events, including severe ones that occur during therapy, can be considered as predictors of only early, but not late, secondary refusals of treatment. Late and recurrent secondary withdrawals from treatment are usually associated with long-term treatment of resistant conditions. Many authors express the opinion that overly complex or frequently changing therapeutic regimens at the same time simply confuse patients, and the long-term absence of a positive effect “pushes” them to independently increase dosages and change the regimen of taking drugs. Such patients, having tried many different drugs and undergoing several courses of therapy, often come to the conclusion that their disease is incurable, and often prefer not to take any drugs at all, citing the lack of positive therapeutic results.

Such patients, having tried many different drugs and undergoing several courses of therapy, often come to the conclusion that their disease is incurable, and often prefer not to take any drugs at all, citing the lack of positive therapeutic results.

H.L. Bischoff [10] pays special attention to the extremely high requirements for treatment, which are characteristic of patients, based on the desire for healing.

Thus, the discrepancy between therapeutic expectations and the real results of the therapy, the previous negative experience of treatment or prolonged hospitalization should be considered as the most significant in the genesis of secondary refusals of patients from therapy. The attitude towards therapy on the part of the patient within the framework of the therapeutic union with the doctor, in our opinion [11], is largely determined by the subjective assessment of the benefits and risks of the therapy. When complications or side effects occur that lead to a decrease in the level of social functioning or a threat to somatic health, despite the simultaneous presence of even significant positive results, patients often tend to evaluate the negative consequences of therapy as more significant for themselves, which often leads to a decision to interrupt ongoing course of treatment. At the same time, the tolerability of therapy significantly depends on the initial attitude of the patient to treatment in general, the quality of his relationship with the doctor, the level of awareness (knowledge) about the effect of the drug and its side effects.

At the same time, the tolerability of therapy significantly depends on the initial attitude of the patient to treatment in general, the quality of his relationship with the doctor, the level of awareness (knowledge) about the effect of the drug and its side effects.

Giving the doctor a decisive role in the doctor-patient dyad, H.I. Kaplan et al. (1994) believe that the level of patient compliance directly depends on some personal characteristics of the doctor (enthusiasm, acceptance range), his age and experience, as well as on the time spent talking with the patient. At the same time, if patients feel that “they were heard” and “fully” discussed their concerns about the upcoming therapy, they subsequently speak out more frankly about the treatment, and do not passively avoid taking the drugs [12].

The physician's authoritarian manner in prescribing therapy often leads to subsequent refusal of treatment. In this regard, some authors openly talk about the need to organize the treatment process on a contractual basis [13].

The majority of patients tend to prefer the outpatient form of therapeutic care, categorically refusing inpatient treatment. At the same time, patients, as a rule, are worried not so much by the unsatisfactory, in their opinion, living conditions of the proposed hospital, but by the alleged restrictions on the freedom to make their own decisions and behavior associated with excessive control by the medical staff. On the contrary, preference for inpatient psychiatric care is more often given by older patients, especially those who are afraid of death or loss of self-care.

Patients who have comprehensive information about their disease, the main effect of drugs and their adverse events, obtained from different sources, are less likely than uninformed patients to interrupt therapy when side effects appear [3]. At the same time, the results of a survey of inpatient patients conducted by J.L. Geller [14] showed that only 8% of them could correctly reproduce the name of at least one drug they were taking, its dosage and the intended effect, and approximately 54% of patients knew practically nothing about their drug therapy. Special surveys conducted among doctors and their patients revealed significant differences in the views of respondents on the need to provide information about drug therapy, as well as the factors that determine consent or refusal [5]. Almost three-quarters of the patients surveyed agreed to receive treatment if they were sure in advance that the drug is both effective and safe, thus confirming the following thesis: patients agree to take the drug only when, regardless of the amount of information they received firmly believe that he can help them, not harm them. However, among the researchers themselves there is still no unanimity on the question: to what extent informed consent insures the patient from refusing therapy in the future and in what form in general, and most importantly, to what extent information is desirable or necessary for patients to make a positive decision about the recommended treatment. treatment?

Special surveys conducted among doctors and their patients revealed significant differences in the views of respondents on the need to provide information about drug therapy, as well as the factors that determine consent or refusal [5]. Almost three-quarters of the patients surveyed agreed to receive treatment if they were sure in advance that the drug is both effective and safe, thus confirming the following thesis: patients agree to take the drug only when, regardless of the amount of information they received firmly believe that he can help them, not harm them. However, among the researchers themselves there is still no unanimity on the question: to what extent informed consent insures the patient from refusing therapy in the future and in what form in general, and most importantly, to what extent information is desirable or necessary for patients to make a positive decision about the recommended treatment. treatment?

Refusal of treatment is the most appropriate focus for compliance therapy [15], and more precisely, motivational therapy (a specific psychotherapeutic technique), aimed primarily at increasing and maintaining a high level of patient compliance throughout the course of treatment. Currently, two methods of compliance therapy are used. The first of them, widely used in our country, is the destructive strategy of "intimidation", "intimidation", which consists in informing the patient about the undesirable risks associated with his possible refusal of treatment and in providing him with the most concise information about the side effects of the drugs used. However, modern theories of medical communication no longer see the patient as an unremarkable, rational "receiver" of care and information from physicians, but rather as a complex individual who constructs highly personalized and unique representations of his health and illness. Based on the fact that the patient is the best source of information about the problems affecting the decision on the need for therapy [16], a more modern and effective strategy for conducting compliance therapy is being built - a rational and explanatory method for creating a true partnership between the doctor and the patient (with division of responsibility and the opportunity to discuss in a dialogue mode the problems that arise in the process of therapy) within the framework of a full-fledged therapeutic alliance.

Currently, two methods of compliance therapy are used. The first of them, widely used in our country, is the destructive strategy of "intimidation", "intimidation", which consists in informing the patient about the undesirable risks associated with his possible refusal of treatment and in providing him with the most concise information about the side effects of the drugs used. However, modern theories of medical communication no longer see the patient as an unremarkable, rational "receiver" of care and information from physicians, but rather as a complex individual who constructs highly personalized and unique representations of his health and illness. Based on the fact that the patient is the best source of information about the problems affecting the decision on the need for therapy [16], a more modern and effective strategy for conducting compliance therapy is being built - a rational and explanatory method for creating a true partnership between the doctor and the patient (with division of responsibility and the opportunity to discuss in a dialogue mode the problems that arise in the process of therapy) within the framework of a full-fledged therapeutic alliance.

The purpose of the first stage of (preparatory) motivational therapy is to provide emotional support to the patient and to establish an extremely trusting relationship with him, as well as to clarify his expectations regarding the upcoming therapy (therapeutic expectations), in particular his doubts and fears about the recommended treatment. Considering your patients' values, cultural beliefs, habits, health and illness is the starting point to shape their commitment to therapy. Medical ethicist A. Frank [17] describes the process of seeking help from a doctor by a patient as “agreement to hear one's story in medical terms”. Before going to the doctor, the patient has already created his own view of his disease and its impact on his own functioning (“subjective theory of disease”). This “subjective picture” of the disease, as a rule, differs significantly from the biologically oriented medical position and represents a “search for explanations of the disease through the eyes of the sufferer” - a cognitive set of the patient's ideas about himself and the world, which makes it possible to partially explain or construct a parallel to the existing scientific biologically oriented theory of disease.

Physicians' expectation that the patient will "give in" to the medical model of disease is a central mistake of specialists, leading to a one-sided view of compliance problems, on the basis of which numerous programs of care for patients with certain chronic disorders are based, focused only on the "medical" model of disease. Asking an open-ended question that encourages or, if necessary, provokes the patient, such as: “Can you explain to me what you would like me to do for you today?”, can reveal their problems, fears and expectations from the visit and therapy. This question gives your patient the opportunity to tell their story in their own language. Studying the factors that increase the motivation of patients with somatic diseases (peptic ulcer, arterial hypertension, diabetes and breast cancer) to therapy, S.H. Kaplan et al. [18] indicate that the expression of sympathy, the unconditional acceptance of everything said by the patient without judgment, criticism or censure, the open expression of emotions, especially negative ones (patients interpret them as a sign of care), are important motivational stimuli for the patient. At the same time, it is necessary to avoid biomedical terms, use the words and expressions heard from patients, prefer the “language of feelings”, which is the point of contact during a therapeutic conversation. In a controlled study of educational programs for patients with diabetes, this approach led to a significant improvement in their ability to provide effective self-care, to neutralize attitudes towards “living with diabetes” and metabolic control [19]. As R. Anderson emphasizes [20]: “doctors can learn to be experts in managing diabetes, but only patients can be experts in their own lives.”

At the same time, it is necessary to avoid biomedical terms, use the words and expressions heard from patients, prefer the “language of feelings”, which is the point of contact during a therapeutic conversation. In a controlled study of educational programs for patients with diabetes, this approach led to a significant improvement in their ability to provide effective self-care, to neutralize attitudes towards “living with diabetes” and metabolic control [19]. As R. Anderson emphasizes [20]: “doctors can learn to be experts in managing diabetes, but only patients can be experts in their own lives.”

The second and main stage of motivational therapy is informing patients. Before this step, it is necessary to determine whether your patient is “information seeker” (i.e., wants to know more about their condition) or “information blind” (i.e., does not want to know the true cause and severity of their condition). Patients today vary considerably in their willingness to participate in therapeutic decision making. Some patients prefer little or no involvement in the therapeutic process. These patients tend to be older, have more serious health problems, are more satisfied with conventional medical care, and have been "learned" to treat and obey the doctor as the expert in prescribing the treatment plan. Other patients who fall into this category find it disrespectful to ask questions of authority such as the doctor. These patients refuse to talk about their problems and need the support and encouragement of the doctor as an authority figure to discuss their point of view on health problems and therapy. At the other end of the spectrum are patients who prefer to be actively involved in decisions about their care and treatment. These patients are usually younger and more educated or have previous experience of self-management of their chronic illness, and are less satisfied with their medical care. They rely on the information available in the print and electronic medical literature and study it before meeting with a doctor to decide whether to choose a doctor or self-medicate.

Some patients prefer little or no involvement in the therapeutic process. These patients tend to be older, have more serious health problems, are more satisfied with conventional medical care, and have been "learned" to treat and obey the doctor as the expert in prescribing the treatment plan. Other patients who fall into this category find it disrespectful to ask questions of authority such as the doctor. These patients refuse to talk about their problems and need the support and encouragement of the doctor as an authority figure to discuss their point of view on health problems and therapy. At the other end of the spectrum are patients who prefer to be actively involved in decisions about their care and treatment. These patients are usually younger and more educated or have previous experience of self-management of their chronic illness, and are less satisfied with their medical care. They rely on the information available in the print and electronic medical literature and study it before meeting with a doctor to decide whether to choose a doctor or self-medicate. These patients, before informing, require clarification of the sources and nature of the information about the disease that they received. Some of this information may be accurate and helpful, and some may be misleading or simply false. In this case, it is necessary to point out these mistakes, help them understand this, expressing respect for them for an active role in organizing their own treatment.

These patients, before informing, require clarification of the sources and nature of the information about the disease that they received. Some of this information may be accurate and helpful, and some may be misleading or simply false. In this case, it is necessary to point out these mistakes, help them understand this, expressing respect for them for an active role in organizing their own treatment.

Most researchers who study the necessary degree of informing patients come to the conclusion that it is expedient to provide maximum information in an accessible and emotionally tolerable form only on those issues that correspond to the requests of the patient about the nature and therapy of his disease. As somewhat declaratively put by Kaplan et al. [5]: "More physician-provided information in response to patient information seeking."

An important role is played by the peculiarities of presenting information that facilitates its assimilation, since it is well known and confirmed by the results of many studies that the patient forgets most of the information that the doctor tells him. In this regard, several provisions should be remembered: the more you speak with the patient or more accurately, the more information that is not required by him is offered by the doctor, the higher the likelihood that the information will be forgotten; instructions and advice are more easily forgotten than other types of information, especially examples from one's own medical practice or, even better, examples from the life of the patient and his relatives; patients remember what they are told first and what they think is most important. At the same time, more intelligent patients remember the same way as less intelligent ones, the elderly remember the same way as younger ones, and patients with moderate anxiety remember better than patients with high and mild anxiety; patients who view their illness as severe remember information best.

In this regard, several provisions should be remembered: the more you speak with the patient or more accurately, the more information that is not required by him is offered by the doctor, the higher the likelihood that the information will be forgotten; instructions and advice are more easily forgotten than other types of information, especially examples from one's own medical practice or, even better, examples from the life of the patient and his relatives; patients remember what they are told first and what they think is most important. At the same time, more intelligent patients remember the same way as less intelligent ones, the elderly remember the same way as younger ones, and patients with moderate anxiety remember better than patients with high and mild anxiety; patients who view their illness as severe remember information best.

The third stage of compliance therapy is supportive, aimed at repeating motivational activities during each patient visit. Particular attention should be paid to the fact that it is at this stage that patients ask many questions regarding the nature of their disease, therapy and preventive measures. A doctor using a motivational strategy should at all costs avoid discussions, especially those in which the doctor advocates for a particular action [21], since the patient's resistance is most often provoked by the doctor's behavior. The motivation enhancement strategy suggests that the use of switching tactics allows the physician to prevent the patient from finding reasons for avoiding medical advice.

A doctor using a motivational strategy should at all costs avoid discussions, especially those in which the doctor advocates for a particular action [21], since the patient's resistance is most often provoked by the doctor's behavior. The motivation enhancement strategy suggests that the use of switching tactics allows the physician to prevent the patient from finding reasons for avoiding medical advice.

Thus, the role of the doctor in the implementation of compliance therapy for chronic mental illness is the most difficult. During a conversation with a patient, he should act as if in two guises.

On the one hand, as a “carrier” of medical biologically oriented knowledge about the etiology, pathogenesis and clinical picture of the disease and its therapy, on the other hand, to conduct a conversation and argue the need for long-term treatment as a “consumer”, based on the ideas of a particular patient about his disease , its causes and characteristics, risks and benefits of drug exposure.

In accordance with the natural reluctance of most people to consider themselves ill after achieving a stable improvement in their condition, withdrawal from therapy is subjectively regarded as one of the stages of psychological recovery.

Diss. doc. honey. Sciences. M., 2009.

Diss. doc. honey. Sciences. M., 2009.

Medical Care 1989;27(Suppl. 3):110–27.

Medical Care 1989;27(Suppl. 3):110–27.

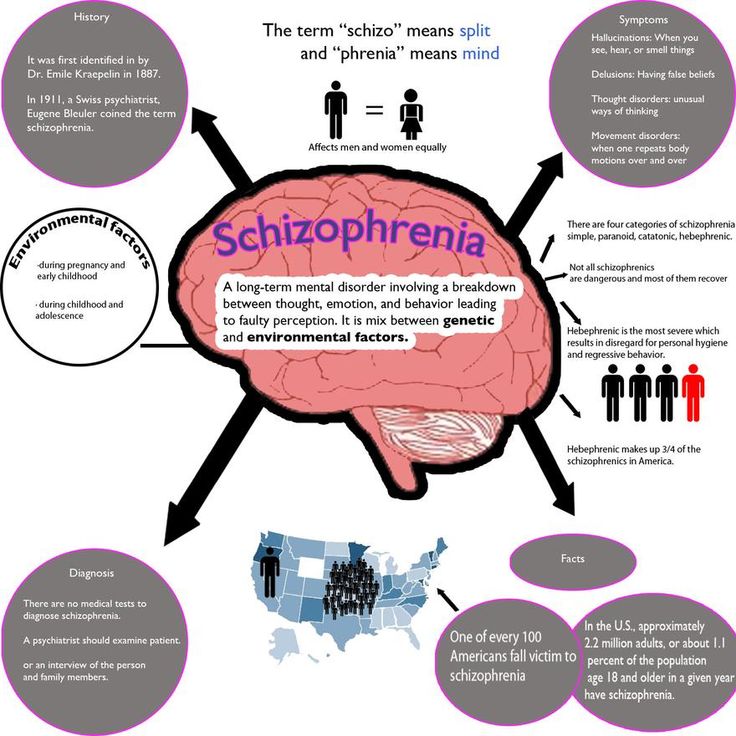

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

A prominent role among mental illnesses is played by syndromes (complexes of symptoms), united in the group of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), which received its name from the Latin terms obsessio and compulsio.

Obsession (lat. obsessio - taxation, siege, blockade).

Compulsions (lat. compello - I force). 1. Obsessive drives, a kind of obsessive phenomena (obsessions). Characterized by irresistible attraction that arises contrary to the mind, will, feelings. Often they are unacceptable to the patient, contrary to his moral and ethical properties. Unlike impulsive drives, compulsions are not realized. These drives are recognized by the patient as wrong and painfully experienced by them, especially since their very appearance, due to its incomprehensibility, often gives rise to a feeling of fear in the patient 2. The term compulsions is also used in a broader sense to refer to any obsessions in the motor sphere, including obsessive rituals.

Characterized by irresistible attraction that arises contrary to the mind, will, feelings. Often they are unacceptable to the patient, contrary to his moral and ethical properties. Unlike impulsive drives, compulsions are not realized. These drives are recognized by the patient as wrong and painfully experienced by them, especially since their very appearance, due to its incomprehensibility, often gives rise to a feeling of fear in the patient 2. The term compulsions is also used in a broader sense to refer to any obsessions in the motor sphere, including obsessive rituals.

In domestic psychiatry, obsessive states were understood as psychopathological phenomena, characterized by the fact that phenomena of a certain content repeatedly appear in the mind of the patient, accompanied by a painful feeling of coercion [Zinoviev PM, 193I]. For N.s. characteristic involuntary, even against the will, the emergence of obsessions with clear consciousness. Although the obsessions are alien, extraneous in relation to the patient's psyche, the patient is not able to get rid of them. They are closely related to the emotional sphere, accompanied by depressive reactions, anxiety. Being symptomatic, according to S.L. Sukhanov [1912], "parasitic", they do not affect the course of intellectual activity in general, remain alien to thinking, do not lead to a decrease in its level, although they worsen the efficiency and productivity of the patient's mental activity. Throughout the course of the disease, a critical attitude is maintained towards obsessions. N.s. conditionally divided into obsessions in the intellectual-affective (phobia) and motor (compulsions) spheres, but most often several of their types are combined in the structure of the disease of obsessions. The isolation of obsessions that are abstract, affectively indifferent, indifferent in their content, for example, arrhythmomania, is rarely justified; An analysis of the psychogenesis of a neurosis often makes it possible to see a pronounced affective (depressive) background at the basis of the obsessive account.

They are closely related to the emotional sphere, accompanied by depressive reactions, anxiety. Being symptomatic, according to S.L. Sukhanov [1912], "parasitic", they do not affect the course of intellectual activity in general, remain alien to thinking, do not lead to a decrease in its level, although they worsen the efficiency and productivity of the patient's mental activity. Throughout the course of the disease, a critical attitude is maintained towards obsessions. N.s. conditionally divided into obsessions in the intellectual-affective (phobia) and motor (compulsions) spheres, but most often several of their types are combined in the structure of the disease of obsessions. The isolation of obsessions that are abstract, affectively indifferent, indifferent in their content, for example, arrhythmomania, is rarely justified; An analysis of the psychogenesis of a neurosis often makes it possible to see a pronounced affective (depressive) background at the basis of the obsessive account. Along with elementary obsessions, the connection of which with psychogeny is obvious, there are “cryptogenic” ones, when the cause of painful experiences is hidden [Svyadoshch L.M., 1959]. N.s. are observed mainly in individuals with a psychasthenic character. This is where apprehensions are especially characteristic. In addition, N.S. occur within the framework of neurosis-like states with sluggish schizophrenia, endogenous depressions, epilepsy, the consequences of a traumatic brain injury, somatic diseases, mainly hypochondria-phobic or nosophobic syndrome. Some researchers distinguish the so-called. "Neurosis of obsessive states", which is characterized by the predominance of obsessive states in the clinical picture - memories that reproduce a psychogenic traumatic situation, thoughts, fears, actions. In genesis play a role: mental trauma; conditioned reflex stimuli that have become pathogenic due to their coincidence with others that previously caused a feeling of fear; situations that have become psychogenic due to the confrontation of opposing tendencies [Svyadoshch A.

Along with elementary obsessions, the connection of which with psychogeny is obvious, there are “cryptogenic” ones, when the cause of painful experiences is hidden [Svyadoshch L.M., 1959]. N.s. are observed mainly in individuals with a psychasthenic character. This is where apprehensions are especially characteristic. In addition, N.S. occur within the framework of neurosis-like states with sluggish schizophrenia, endogenous depressions, epilepsy, the consequences of a traumatic brain injury, somatic diseases, mainly hypochondria-phobic or nosophobic syndrome. Some researchers distinguish the so-called. "Neurosis of obsessive states", which is characterized by the predominance of obsessive states in the clinical picture - memories that reproduce a psychogenic traumatic situation, thoughts, fears, actions. In genesis play a role: mental trauma; conditioned reflex stimuli that have become pathogenic due to their coincidence with others that previously caused a feeling of fear; situations that have become psychogenic due to the confrontation of opposing tendencies [Svyadoshch A. M., 1982]. It should be noted that these same authors emphasize that N.s.c. occurs with various character traits, but most often in psychasthenic personalities.

M., 1982]. It should be noted that these same authors emphasize that N.s.c. occurs with various character traits, but most often in psychasthenic personalities.

Currently, almost all obsessive-compulsive disorders are united in the International Classification of Diseases under the concept of "obsessive-compulsive disorder".

OKR concepts have undergone a fundamental reassessment over the past 15 years. During this time, the clinical and epidemiological significance of OCD has been completely revised. If it was previously thought that this is a rare condition observed in a small number of people, now it is known that OCD is common and causes a high percentage of morbidity, which requires the urgent attention of psychiatrists around the world. Parallel to this, our understanding of the etiology of OCD has broadened: the vaguely formulated psychoanalytic definition of the past two decades has been replaced by a neurochemical paradigm that explores the neurotransmitter disorders that underlie OCD. And most importantly, pharmacological interventions specifically targeting serotonergic neurotransmission have revolutionized the prospects for recovery for millions of OCD patients worldwide.

And most importantly, pharmacological interventions specifically targeting serotonergic neurotransmission have revolutionized the prospects for recovery for millions of OCD patients worldwide.

The discovery that intense serotonin reuptake inhibition (SSRI) was the key to effective treatment for OCD was the first step in a revolution and spurred clinical research that showed the efficacy of such selective inhibitors.

As described in ICD-10, the main features of OCD are repetitive intrusive (obsessive) thoughts and compulsive actions (rituals).

In a broad sense, the core of OCD is the syndrome of obsession, which is a condition with a predominance in the clinical picture of feelings, thoughts, fears, memories that arise in addition to the desire of patients, but with awareness of their pain and a critical attitude towards them. Despite the understanding of the unnaturalness, illogicality of obsessions and states, patients are powerless in their attempts to overcome them. Obsessional impulses or ideas are recognized as alien to the personality, but as if coming from within. Obsessions can be the performance of rituals designed to alleviate anxiety, such as washing hands to combat "pollution" and to prevent "infection". Attempts to drive away unwelcome thoughts or urges can lead to severe internal struggle, accompanied by intense anxiety.

Obsessional impulses or ideas are recognized as alien to the personality, but as if coming from within. Obsessions can be the performance of rituals designed to alleviate anxiety, such as washing hands to combat "pollution" and to prevent "infection". Attempts to drive away unwelcome thoughts or urges can lead to severe internal struggle, accompanied by intense anxiety.

Obsessions in the ICD-10 are included in the group of neurotic disorders.

The prevalence of OCD in the population is quite high. According to some data, it is determined by an indicator of 1.5% (meaning "fresh" cases of diseases) or 2-3%, if episodes of exacerbations observed throughout life are taken into account. Those suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder make up 1% of all patients receiving treatment in psychiatric institutions. It is believed that men and women are affected approximately equally.

CLINICAL PICTURE

The problem of obsessive-compulsive disorders attracted the attention of clinicians already at the beginning of the 17th century. They were first described by Platter in 1617. In 1621 E. Barton described an obsessive fear of death. Mentions of obsessions are found in the writings of F. Pinel (1829). I. Balinsky proposed the term "obsessive ideas", which took root in Russian psychiatric literature. In 1871, Westphal coined the term "agoraphobia" to refer to the fear of being in public places. M. Legrand de Sol [1875], analyzing the features of the dynamics of OCD in the form of "insanity of doubt with delusions of touch, points to a gradually becoming more complicated clinical picture - obsessive doubts are replaced by ridiculous fears of" touch "to surrounding objects, motor rituals join, the fulfillment of which is subject to the whole life sick. However, only at the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. researchers were able to more or less clearly describe the clinical picture and give syndromic characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorders. The onset of the disease usually occurs in adolescence and adolescence. The maximum of clinically defined manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder is observed in the age range of 10-25 years.

They were first described by Platter in 1617. In 1621 E. Barton described an obsessive fear of death. Mentions of obsessions are found in the writings of F. Pinel (1829). I. Balinsky proposed the term "obsessive ideas", which took root in Russian psychiatric literature. In 1871, Westphal coined the term "agoraphobia" to refer to the fear of being in public places. M. Legrand de Sol [1875], analyzing the features of the dynamics of OCD in the form of "insanity of doubt with delusions of touch, points to a gradually becoming more complicated clinical picture - obsessive doubts are replaced by ridiculous fears of" touch "to surrounding objects, motor rituals join, the fulfillment of which is subject to the whole life sick. However, only at the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. researchers were able to more or less clearly describe the clinical picture and give syndromic characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorders. The onset of the disease usually occurs in adolescence and adolescence. The maximum of clinically defined manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder is observed in the age range of 10-25 years.

Main clinical manifestations of OCD:

Obsessional thoughts - painful, arising against the will, but recognized by the patient as their own, ideas, beliefs, images, which in a stereotyped form forcibly invade the patient's consciousness and which he tries to resist in some way. It is this combination of an inner sense of compulsive urge and efforts to resist it that characterizes obsessional symptoms, but of the two, the degree of effort exerted is the more variable. Obsessive thoughts may take the form of single words, phrases, or lines of poetry; they are usually unpleasant to the patient and may be obscene, blasphemous, or even shocking.

Obsessional imagery is vivid scenes, often violent or disgusting, including, for example, sexual perversion.

Obsessional impulses are urges to do things that are usually destructive, dangerous or shameful; for example, jumping into the road in front of a moving car, injuring a child, or shouting obscene words while in society.

Obsessional rituals include both mental activities (eg, counting repeatedly in a particular way, or repeating certain words) and repetitive but meaningless acts (eg, washing hands twenty or more times a day). Some of them have an understandable connection with the obsessive thoughts that preceded them, for example, repeated washing of hands - with thoughts of infection. Other rituals (for example, regularly laying out clothes in some complex system before putting them on) do not have such a connection. Some patients feel an irresistible urge to repeat such actions a certain number of times; if that fails, they are forced to start all over again. Patients are invariably aware that their rituals are illogical and usually try to hide them. Some fear that such symptoms are a sign of the onset of insanity. Both obsessive thoughts and rituals inevitably lead to problems in daily activities.

Obsessive rumination (“mental chewing gum”) is an internal debate in which the arguments for and against even the simplest everyday actions are endlessly revised. Some obsessive doubts relate to actions that may have been incorrectly performed or not completed, such as turning off the gas stove faucet or locking the door; others concern actions that could harm other people (for example, the possibility of driving past a cyclist in a car, knocking him down). Sometimes doubts are associated with a possible violation of religious prescriptions and rituals - “remorse of conscience”.

Some obsessive doubts relate to actions that may have been incorrectly performed or not completed, such as turning off the gas stove faucet or locking the door; others concern actions that could harm other people (for example, the possibility of driving past a cyclist in a car, knocking him down). Sometimes doubts are associated with a possible violation of religious prescriptions and rituals - “remorse of conscience”.

Compulsive actions - repetitive stereotypical actions, sometimes acquiring the character of protective rituals. The latter are aimed at preventing any objectively unlikely events that are dangerous for the patient or his relatives.

In addition to the above, in a number of obsessive-compulsive disorders, a number of well-defined symptom complexes stand out, and among them are obsessive doubts, contrasting obsessions, obsessive fears - phobias (from the Greek. phobos).

Obsessive thoughts and compulsive rituals may intensify in certain situations; for example, obsessive thoughts about harming other people often become more persistent in the kitchen or some other place where knives are kept. Since patients often avoid such situations, there may be a superficial resemblance to the characteristic avoidance pattern found in phobic anxiety disorder. Anxiety is an important component of obsessive-compulsive disorders. Some rituals reduce anxiety, while after others it increases. Obsessions often develop as part of depression. In some patients, this appears to be a psychologically understandable reaction to obsessive-compulsive symptoms, but in other patients, recurrent episodes of depressive mood occur independently.

Since patients often avoid such situations, there may be a superficial resemblance to the characteristic avoidance pattern found in phobic anxiety disorder. Anxiety is an important component of obsessive-compulsive disorders. Some rituals reduce anxiety, while after others it increases. Obsessions often develop as part of depression. In some patients, this appears to be a psychologically understandable reaction to obsessive-compulsive symptoms, but in other patients, recurrent episodes of depressive mood occur independently.

Obsessions (obsessions) are divided into figurative or sensual, accompanied by the development of affect (often painful) and obsessions of affectively neutral content.

Sensual obsessions include obsessive doubts, memories, ideas, drives, actions, fears, an obsessive feeling of antipathy, an obsessive fear of habitual actions.

Obsessive doubts - intrusively arising contrary to logic and reason, uncertainty about the correctness of committed and committed actions. The content of doubts is different: obsessive everyday fears (whether the door is locked, whether windows or water taps are closed tightly enough, whether gas and electricity are turned off), doubts related to official activities (whether this or that document is written correctly, whether the addresses on business papers are mixed up , whether inaccurate figures are indicated, whether orders are correctly formulated or executed), etc. Despite repeated verification of the committed action, doubts, as a rule, do not disappear, causing psychological discomfort in the person suffering from this kind of obsession.

The content of doubts is different: obsessive everyday fears (whether the door is locked, whether windows or water taps are closed tightly enough, whether gas and electricity are turned off), doubts related to official activities (whether this or that document is written correctly, whether the addresses on business papers are mixed up , whether inaccurate figures are indicated, whether orders are correctly formulated or executed), etc. Despite repeated verification of the committed action, doubts, as a rule, do not disappear, causing psychological discomfort in the person suffering from this kind of obsession.

Obsessive memories include persistent, irresistible painful memories of any sad, unpleasant or shameful events for the patient, accompanied by a sense of shame, repentance. They dominate the mind of the patient, despite the efforts and efforts not to think about them.

Obsessive impulses - urges to commit one or another tough or extremely dangerous action, accompanied by a feeling of horror, fear, confusion with the inability to get rid of it. The patient is seized, for example, by the desire to throw himself under a passing train or push a loved one under it, to kill his wife or child in an extremely cruel way. At the same time, patients are painfully afraid that this or that action will be implemented.

The patient is seized, for example, by the desire to throw himself under a passing train or push a loved one under it, to kill his wife or child in an extremely cruel way. At the same time, patients are painfully afraid that this or that action will be implemented.

Manifestations of obsessive ideas can be different. In some cases, this is a vivid "vision" of the results of obsessive drives, when patients imagine the result of a cruel act committed. In other cases, obsessive ideas, often referred to as mastering, appear in the form of implausible, sometimes absurd situations that patients take for real. An example of obsessive ideas is the patient's conviction that the buried relative was alive, and the patient painfully imagines and experiences the suffering of the deceased in the grave. At the height of obsessive ideas, the consciousness of their absurdity, implausibility disappears and, on the contrary, confidence in their reality appears. As a result, obsessions acquire the character of overvalued formations (dominant ideas that do not correspond to their true meaning), and sometimes delusions.

An obsessive feeling of antipathy (as well as obsessive blasphemous and blasphemous thoughts) - unjustified, driven away by the patient from himself antipathy towards a certain, often close person, cynical, unworthy thoughts and ideas in relation to respected people, in religious persons - in relation to saints or ministers churches.

Obsessive acts are acts done against the wishes of the sick, despite efforts made to restrain them. Some of the obsessive actions burden the patients until they are realized, others are not noticed by the patients themselves. Obsessive actions are painful for patients, especially in those cases when they become the object of attention of others.

Obsessive fears, or phobias, include an obsessive and senseless fear of heights, large streets, open or confined spaces, large crowds of people, the fear of sudden death, the fear of falling ill with one or another incurable disease. Some patients may develop a wide variety of phobias, sometimes acquiring the character of fear of everything (panphobia). And finally, an obsessive fear of the emergence of fears (phobophobia) is possible.

And finally, an obsessive fear of the emergence of fears (phobophobia) is possible.

Hypochondriacal phobias (nosophobia) - an obsessive fear of some serious illness. Most often, cardio-, stroke-, syphilo- and AIDS phobias are observed, as well as the fear of the development of malignant tumors. At the peak of anxiety, patients sometimes lose their critical attitude to their condition - they turn to doctors of the appropriate profile, require examination and treatment. The implementation of hypochondriacal phobias occurs both in connection with psycho- and somatogenic (general non-mental illnesses) provocations, and spontaneously. As a rule, hypochondriacal neurosis develops as a result, accompanied by frequent visits to doctors and unreasonable medication.

Specific (isolated) phobias - obsessive fears limited to a strictly defined situation - fear of heights, nausea, thunderstorms, pets, treatment at the dentist, etc. Since contact with situations that cause fear is accompanied by intense anxiety, the patients tend to avoid them.

Obsessive fears are often accompanied by the development of rituals - actions that have the meaning of "magic" spells that are performed, despite the critical attitude of the patient to obsession, in order to protect against one or another imaginary misfortune: before starting any important business, the patient must perform some that specific action to eliminate the possibility of failure. Rituals can, for example, be expressed in snapping fingers, playing a melody to the patient or repeating certain phrases, etc. In these cases, even relatives are not aware of the existence of such disorders. Rituals, combined with obsessions, are a fairly stable system that usually exists for many years and even decades.

Obsessions of affectively neutral content - obsessive sophistication, obsessive counting, recalling neutral events, terms, formulations, etc. Despite their neutral content, they burden the patient, interfere with his intellectual activity.

Contrasting obsessions ("aggressive obsessions") - blasphemous, blasphemous thoughts, fear of harming oneself and others. Psychopathological formations of this group refer mainly to figurative obsessions with pronounced affective saturation and ideas that take possession of the consciousness of patients. They are distinguished by a sense of alienation, the absolute lack of motivation of the content, as well as a close combination with obsessive drives and actions. Patients with contrasting obsessions and complain of an irresistible desire to add endings to the replicas they have just heard, giving an unpleasant or threatening meaning to what has been said, to repeat after those around them, but with a touch of irony or malice, phrases of religious content, to shout out cynical words that contradict their own attitudes and generally accepted morality. , they may experience fear of losing control of themselves and possibly committing dangerous or ridiculous actions, injuring themselves or their loved ones. In the latter cases, obsessions are often combined with object phobias (fear of sharp objects - knives, forks, axes, etc.

Psychopathological formations of this group refer mainly to figurative obsessions with pronounced affective saturation and ideas that take possession of the consciousness of patients. They are distinguished by a sense of alienation, the absolute lack of motivation of the content, as well as a close combination with obsessive drives and actions. Patients with contrasting obsessions and complain of an irresistible desire to add endings to the replicas they have just heard, giving an unpleasant or threatening meaning to what has been said, to repeat after those around them, but with a touch of irony or malice, phrases of religious content, to shout out cynical words that contradict their own attitudes and generally accepted morality. , they may experience fear of losing control of themselves and possibly committing dangerous or ridiculous actions, injuring themselves or their loved ones. In the latter cases, obsessions are often combined with object phobias (fear of sharp objects - knives, forks, axes, etc. ). The contrasting group also partially includes obsessions of sexual content (obsessions of the type of forbidden ideas about perverted sexual acts, the objects of which are children, representatives of the same sex, animals).

). The contrasting group also partially includes obsessions of sexual content (obsessions of the type of forbidden ideas about perverted sexual acts, the objects of which are children, representatives of the same sex, animals).

Obsessions of pollution (mysophobia). This group of obsessions includes both the fear of pollution (earth, dust, urine, feces and other impurities), as well as the fear of penetration into the body of harmful and toxic substances (cement, fertilizers, toxic waste), small objects (glass fragments, needles, specific types of dust), microorganisms. In some cases, the fear of contamination can be limited, remain at the preclinical level for many years, manifesting itself only in some features of personal hygiene (frequent change of linen, repeated washing of hands) or in housekeeping (thorough handling of food, daily washing of floors). , "taboo" on pets). This kind of monophobia does not significantly affect the quality of life and is evaluated by others as habits (exaggerated cleanliness, excessive disgust). Clinically manifested variants of mysophobia belong to the group of severe obsessions. In these cases, gradually becoming more complex protective rituals come to the fore: avoiding sources of pollution and touching "unclean" objects, processing things that could get dirty, a certain sequence in the use of detergents and towels, which allows you to maintain "sterility" in the bathroom. Stay outside the apartment is also furnished with a series of protective measures: going out into the street in special clothing that covers the body as much as possible, special processing of wearable items upon returning home. In the later stages of the disease, patients, avoiding pollution, not only do not go out, but do not even leave their own room. In order to avoid contacts and contacts that are dangerous in terms of contamination, patients do not allow even their closest relatives to come near them. Mysophobia is also related to the fear of contracting a disease, which does not belong to the categories of hypochondriacal phobias, since it is not determined by fears that a person suffering from OCD has a particular disease.

Clinically manifested variants of mysophobia belong to the group of severe obsessions. In these cases, gradually becoming more complex protective rituals come to the fore: avoiding sources of pollution and touching "unclean" objects, processing things that could get dirty, a certain sequence in the use of detergents and towels, which allows you to maintain "sterility" in the bathroom. Stay outside the apartment is also furnished with a series of protective measures: going out into the street in special clothing that covers the body as much as possible, special processing of wearable items upon returning home. In the later stages of the disease, patients, avoiding pollution, not only do not go out, but do not even leave their own room. In order to avoid contacts and contacts that are dangerous in terms of contamination, patients do not allow even their closest relatives to come near them. Mysophobia is also related to the fear of contracting a disease, which does not belong to the categories of hypochondriacal phobias, since it is not determined by fears that a person suffering from OCD has a particular disease. In the foreground is the fear of a threat from the outside: the fear of pathogenic bacteria entering the body. Hence the development of appropriate protective actions.

In the foreground is the fear of a threat from the outside: the fear of pathogenic bacteria entering the body. Hence the development of appropriate protective actions.