Ocd eating disorders

International OCD Foundation | The Relationship Between Eating Disorders and OCD Part of the Spectrum

By Fugen Neziroglu, PhD, ABBP, ABPP and Jonathan Sandler, BA

This article was initially published in the Summer 2009 edition of the OCD Newsletter.

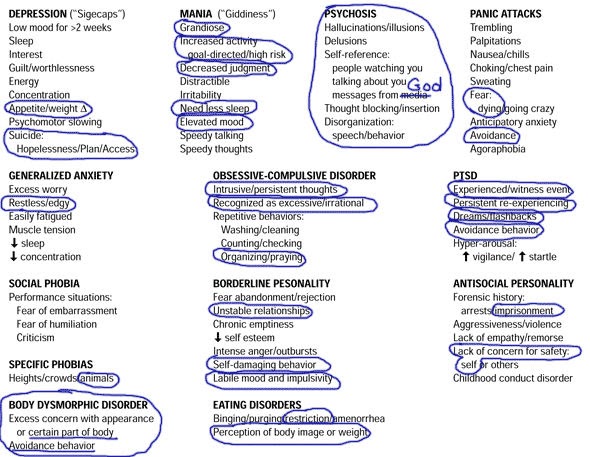

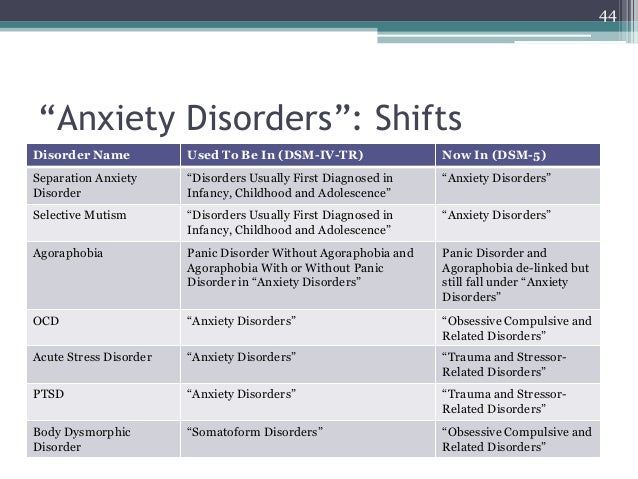

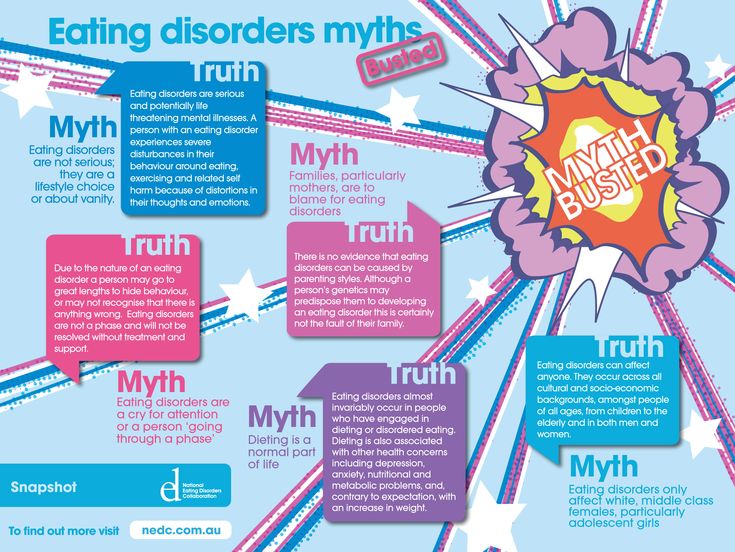

When people think of eating disorders, they conjure up images of adolescents performing rituals around food and obsessing about what to eat, how much, whether the food will be easily digested or whether the food will sit in their stomachs and make them look ugly. Others think of individuals with eating disorders appearing very similar to those with body dysmorphic disorder, both being very preoccupied with their body image. However, most people do not think of eating disorders as being part of the OCD spectrum, and the relationship between the two disorders has gone relatively unstudied. Even more troubling is the fact that when patients seek help from mental health professionals in order to alleviate their suffering, clinicians may often mistake one for the other.

In other words, since the behaviors that result from both OCD and eating disorders may appear so similar, it might be difficult to determine which of the two disorders the patient actually has if both are simultaneously present, and if so, which disorder is mainly responsible for bringing about the other.

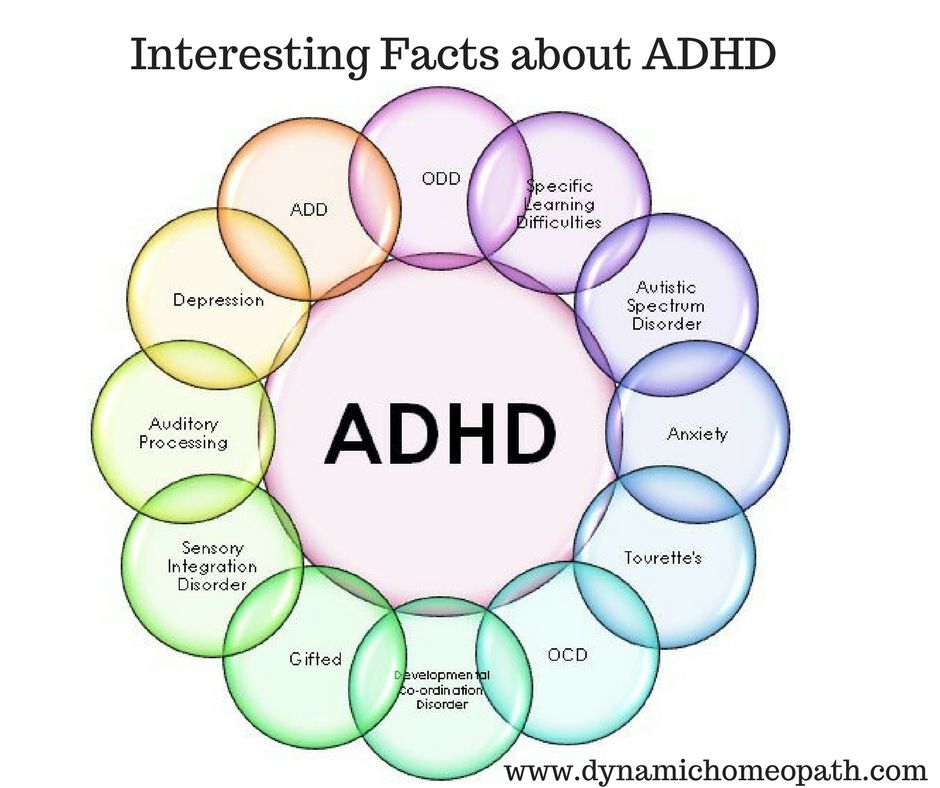

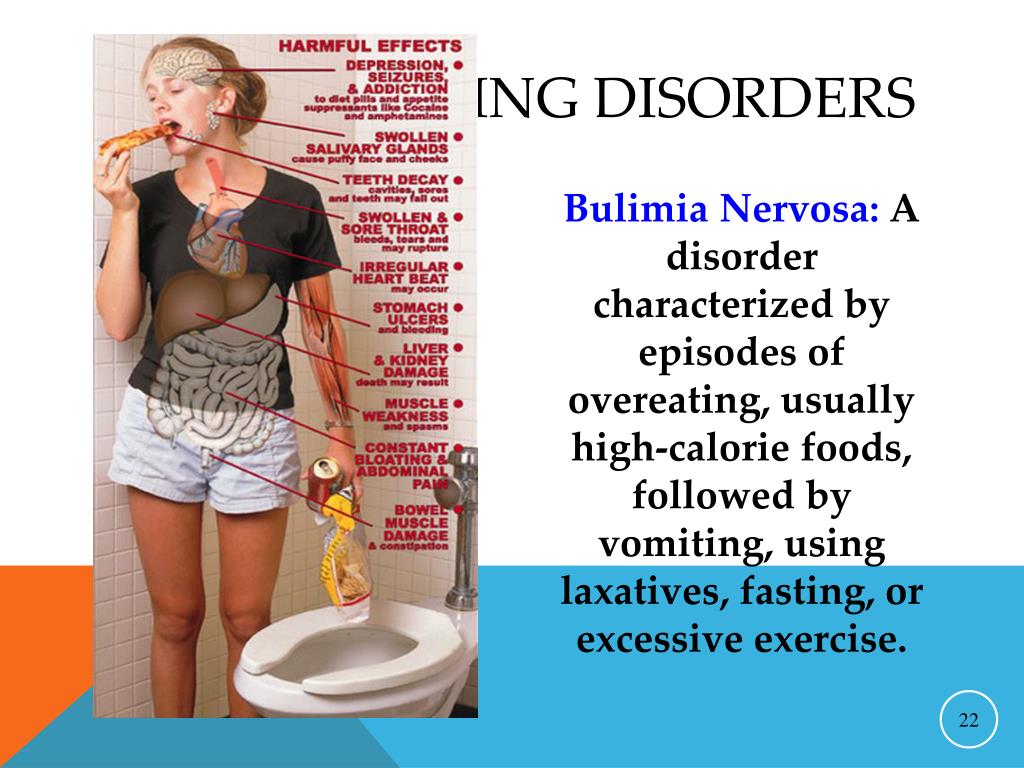

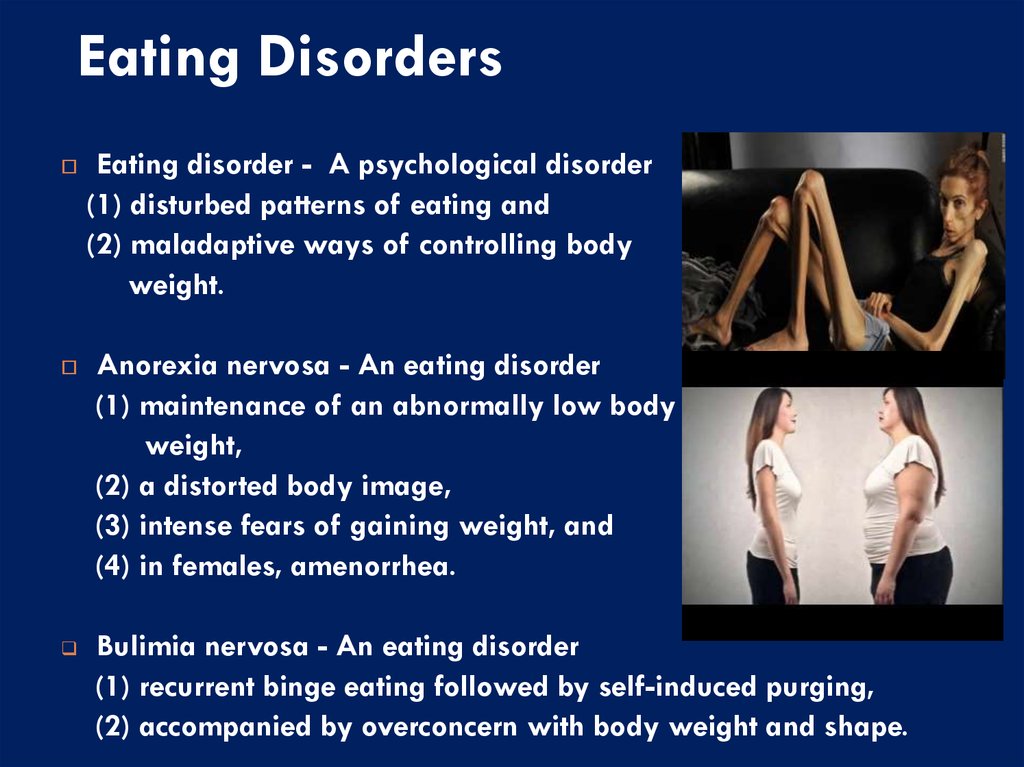

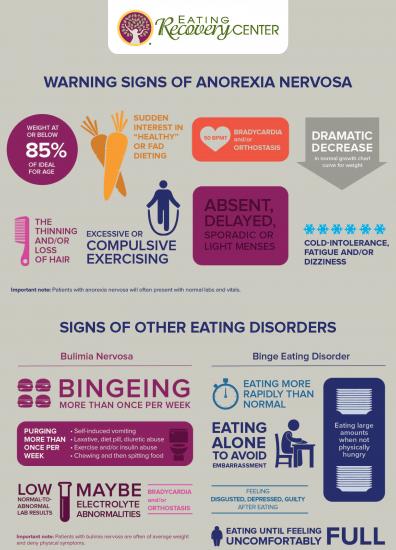

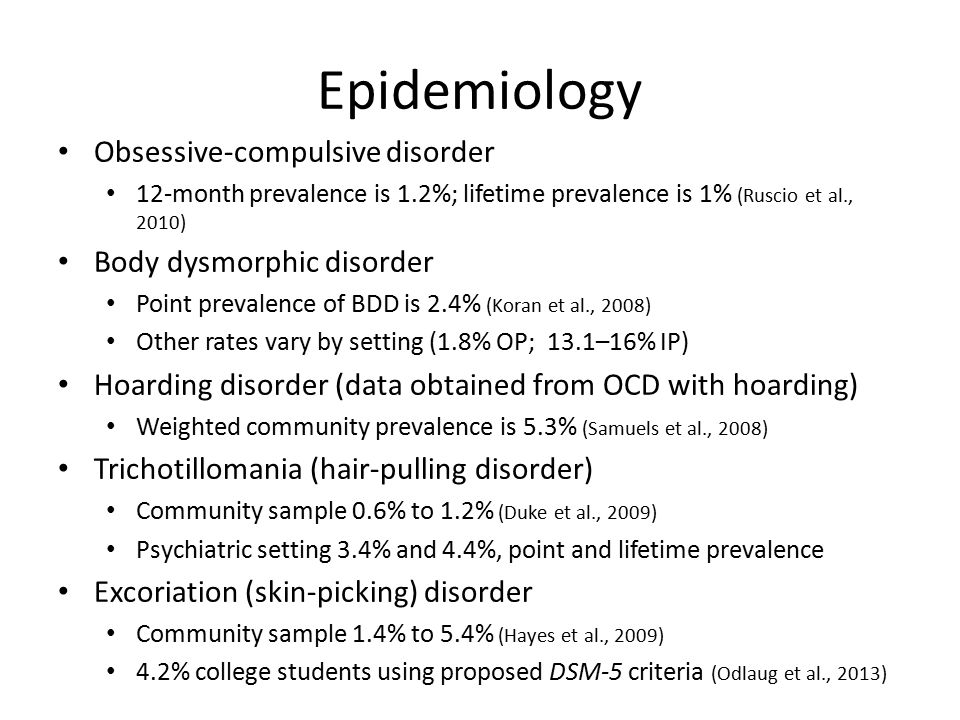

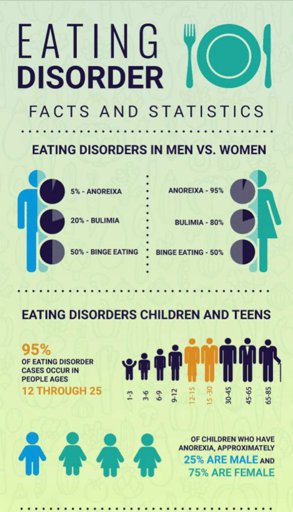

Ever since 1939 researchers have speculated on the parallels between OCD and eating disorders. Numerous studies have now shown that those with eating disorders have statistically higher rates of OCD (11% – 69%), and vice versa (10% – 17%). As recently as 2004, Kaye, et al., reported that 64% of individuals with eating disorders also possess at least one anxiety disorder, and 41% of these individuals have OCD in particular. In 1983, Yaryura-Tobias and Neziroglu proposed that eating disorders may be considered part of the OCD spectrumm but since then the boundaries among anorexia, nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and OCD remain blurred. Thus, the challenge for clinicians becomes recognizing whether the condition is a particular form of OCD, or actually an entirely separate but related disorder with symptoms that merely have an obsessive-compulsive quality to them. More specifically, individuals who suffer from anorexia commonly diet and exercise excessively; those with bulimia usually develop a vicious cycle of binging and purging. In both instances, extreme and often life-threatening behaviors that consist of either consuming too little or too much food typically stem from intrusive obsessive thoughts. Anorexics, in particular, exhibit faulty perceptions of body image, an irrational fear of gaining weight, and other food-related obsessions thereby leading to the categorical refusal to eat. As for bulimics, their disorder is characterized by a consumption of abnormally large quantities of food, followed by overwhelming feelings of guilt and shame. In other words, the sense of helplessness or lack of control they experience during binge periods ultimately gives way to obsessions of physical sickness and self-disgust afterwards.

More specifically, individuals who suffer from anorexia commonly diet and exercise excessively; those with bulimia usually develop a vicious cycle of binging and purging. In both instances, extreme and often life-threatening behaviors that consist of either consuming too little or too much food typically stem from intrusive obsessive thoughts. Anorexics, in particular, exhibit faulty perceptions of body image, an irrational fear of gaining weight, and other food-related obsessions thereby leading to the categorical refusal to eat. As for bulimics, their disorder is characterized by a consumption of abnormally large quantities of food, followed by overwhelming feelings of guilt and shame. In other words, the sense of helplessness or lack of control they experience during binge periods ultimately gives way to obsessions of physical sickness and self-disgust afterwards.

In the cases of both anorexia and bulimia, obsessions lead to levels of anxiety that can only be reduced by ritualistic compulsions. The compulsive behaviors of anorexics can often be seen in their careful procedures of selecting, buying, preparing, cooking, ornamenting, and eventually consuming food. Just as with OCD, compulsions are commonly strengthened by many other personality traits, such as uncertainty, meticulousness rigidity, and perfectionism (Yaryura-Tobiast al. 2001). Anorexics also often exhibit overvalued ideation, cognitive distortions, such as all-or-none thinking, and attempts to gain control of their environment. For bulimics, the need to feel relieved of the obsessive guilt and shame following binges causes them to compulsively purge the food they consumed, repeating the cycle over and over again. Here too, perfectionism an excessive desire for social approval or acceptance, and bouts of anxiety or depression play a major role.

The compulsive behaviors of anorexics can often be seen in their careful procedures of selecting, buying, preparing, cooking, ornamenting, and eventually consuming food. Just as with OCD, compulsions are commonly strengthened by many other personality traits, such as uncertainty, meticulousness rigidity, and perfectionism (Yaryura-Tobiast al. 2001). Anorexics also often exhibit overvalued ideation, cognitive distortions, such as all-or-none thinking, and attempts to gain control of their environment. For bulimics, the need to feel relieved of the obsessive guilt and shame following binges causes them to compulsively purge the food they consumed, repeating the cycle over and over again. Here too, perfectionism an excessive desire for social approval or acceptance, and bouts of anxiety or depression play a major role.

In both anorexia and bulimia the individual clearly becomes preoccupied by incessant thoughts revolving around body image, weight gain, and food intake, leading to ritualistic methods of eating dieting and exercising. The common thread linking both of these disorders to OCD is the overwhelming presence of obsessions and compulsions that eventually affects the individual’s daily functioning, even to the extent of becoming incapacitated. Just as the OCD sufferer feels as though the door is not locked, despite evidence to the contrary, and is then compelled to check those locks hundreds of times in order to remove this doubt, so too the anorexic feels as though she is fat despite the reality the mirror portrays, and she is thus forever checking her stomach to make sure that she has not gained weight, but she is never satisfied and therefore she is compelled to lose weight by any means necessary. As with an OCD sufferer who can never achieve that “just right” feeling on a specific task, so too is a bulimic prevented from ever reaching his or her goals of fullness and emptiness in an endless binge-purge cycle. Going one step further there are many instances in which patients demonstrate behaviors that at first glance appear to be indicative of an eating disorder, but actually turn out to be a result of OCD.

The common thread linking both of these disorders to OCD is the overwhelming presence of obsessions and compulsions that eventually affects the individual’s daily functioning, even to the extent of becoming incapacitated. Just as the OCD sufferer feels as though the door is not locked, despite evidence to the contrary, and is then compelled to check those locks hundreds of times in order to remove this doubt, so too the anorexic feels as though she is fat despite the reality the mirror portrays, and she is thus forever checking her stomach to make sure that she has not gained weight, but she is never satisfied and therefore she is compelled to lose weight by any means necessary. As with an OCD sufferer who can never achieve that “just right” feeling on a specific task, so too is a bulimic prevented from ever reaching his or her goals of fullness and emptiness in an endless binge-purge cycle. Going one step further there are many instances in which patients demonstrate behaviors that at first glance appear to be indicative of an eating disorder, but actually turn out to be a result of OCD. As an illustration, consider the OCD sufferer who may lose weight excessively and appear anorexic yet is doing so merely as the result of contamination concerns or time-consuming rituals that prevent him or her from eating on a regular basis. Conversely, consider the anorexic patient who seems to be engaging in obsessive-compulsive rituals of cutting or weighing food, yet only doing so in the hopes of restricting food intake and losing weight in the process. The potential for one disorder to appear as the other is virtually endless; below is just a small list comparing the very different underlying causes of strikingly similar behaviors in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder versus those with eating disorders.

As an illustration, consider the OCD sufferer who may lose weight excessively and appear anorexic yet is doing so merely as the result of contamination concerns or time-consuming rituals that prevent him or her from eating on a regular basis. Conversely, consider the anorexic patient who seems to be engaging in obsessive-compulsive rituals of cutting or weighing food, yet only doing so in the hopes of restricting food intake and losing weight in the process. The potential for one disorder to appear as the other is virtually endless; below is just a small list comparing the very different underlying causes of strikingly similar behaviors in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder versus those with eating disorders.

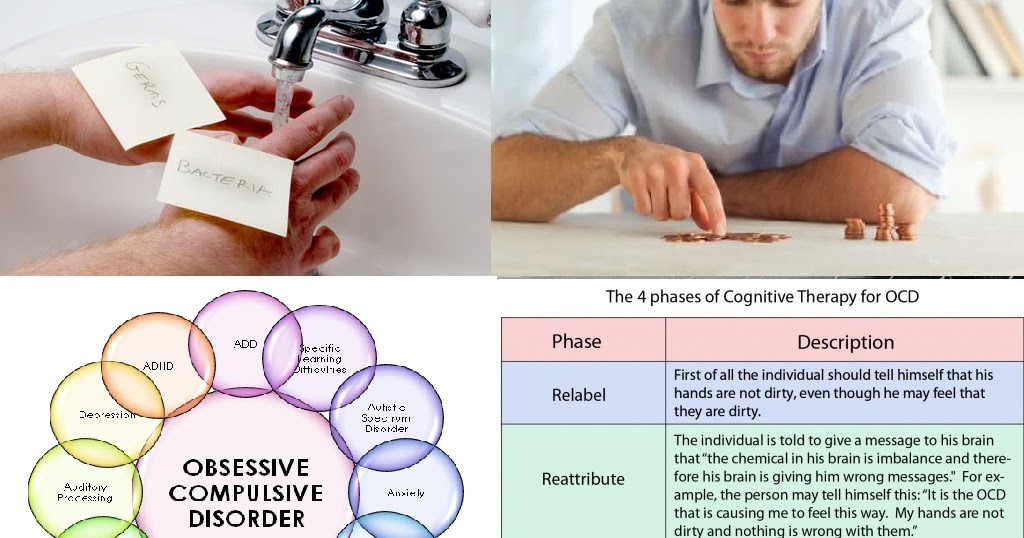

Individual counts the number of mouthfuls chewed or pieces of food in a meal according to some fixed or magical number that is “correct” or “just right.” Individual counts mouthfuls or pieces of food as a means of limiting portions, and thus effectively losing more weight. Individual repeatedly washes hands due to a fear of germs, contact with waste products, or a number of other sources of possible contamination that exist. Individual excessively washes hands to remove trace amounts of oil that might cause weight gain if ingested. Individual throws out food in a can that has been slightly dented for fear that it might contain food poisoning and later cause serious illness to someone. Individual throws out food in a can because it was discovered to contain too many calories after reading the label. Individual repeatedly asks a waiter in a restaurant about different dishes on menu doubtful that he or she has enough knowledge to make the perfect meal decision. Individual constantly asks same waiter about contents of dishes so as to stay away from having any butter oil or fat. Individual refuses to enter the kitchen in order to eat due to fear of accidentally mixing cleaning items with the food. Individual refuses to enter the same room for it will only lead to the temptation to eat and thus get fat.

Individual repeatedly washes hands due to a fear of germs, contact with waste products, or a number of other sources of possible contamination that exist. Individual excessively washes hands to remove trace amounts of oil that might cause weight gain if ingested. Individual throws out food in a can that has been slightly dented for fear that it might contain food poisoning and later cause serious illness to someone. Individual throws out food in a can because it was discovered to contain too many calories after reading the label. Individual repeatedly asks a waiter in a restaurant about different dishes on menu doubtful that he or she has enough knowledge to make the perfect meal decision. Individual constantly asks same waiter about contents of dishes so as to stay away from having any butter oil or fat. Individual refuses to enter the kitchen in order to eat due to fear of accidentally mixing cleaning items with the food. Individual refuses to enter the same room for it will only lead to the temptation to eat and thus get fat. Individual repeatedly checks refrigerator shelves or other parts of house in order to make sure that every piece of food bought is in its proper designated place. Individual constantly checks same locations in search of food to eat in an extensive bulimic binge period.

Individual repeatedly checks refrigerator shelves or other parts of house in order to make sure that every piece of food bought is in its proper designated place. Individual constantly checks same locations in search of food to eat in an extensive bulimic binge period.

Thus in order to differentiate between the two disorders and make the proper diagnosis, it is crucial for the clinician to more closely examine the specific behaviors that are being observed and the motivations behind those behaviors. Whereas patients with eating disorders are primarily driven by concerns of physical appearance, and consequently alter their eating patterns in order to lose weight accordingly. OCD patients may be restricting their eating for reasons very different than body image concerns. Furthermore, for cases in which an individual qualifies for both diagnoses, such as an anorexic or bulimic who also experiences non-food related OCD symptoms, like checking or contamination, it is still imperative to consider whether or not their symptoms are being motivated by both disorders simultaneously. For example, consider a patient washing his/her groceries due to the fear of contamination as well as the fear that the products may contain high fat ingredients.

For example, consider a patient washing his/her groceries due to the fear of contamination as well as the fear that the products may contain high fat ingredients.

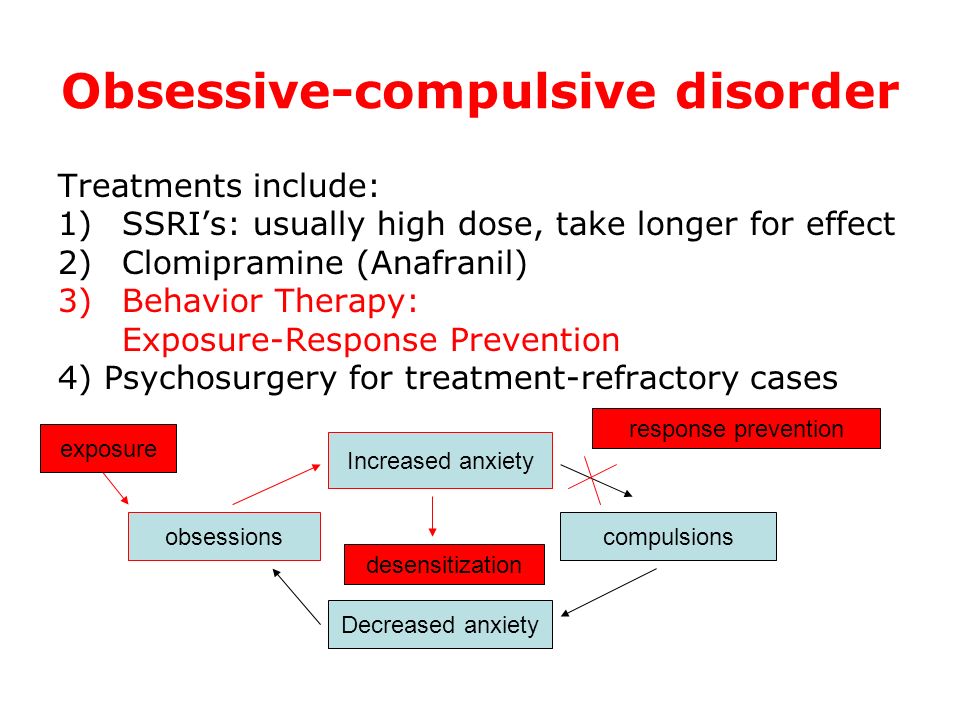

It should be noted that the recommended psychological treatment for both OCD and eating disorders usually involves some combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy, antidepressant medication, and family counseling. Successful treatment for bulimics in particular often entails classic exposure and response prevention, in which patients are exposed to their favorite foods, asked to eat, and then prevented with careful monitoring from vomiting using laxatives or otherwise purging. Additional techniques involve gradual alteration of eating rituals and increased flexibility in eating behaviors which may include breaking rituals such as the need to use the same utensils to measure food, to time meals, and to avoid certain restaurants. Because eating disorders typically result in numerous medical complications, we strongly encourage physicians and nutritionists to be part of the team.

Significant advancements have recently been made in both the diagnosis and treatment of OCD and eating disorders as separate entities, but ample scientific research into the connection between the two, the commonality of their symptoms, and the possible biochemical similarities behind, them is presently lacking. Fortunately, some of the most promising psychiatric investigations into the overlapping symptoms of spectrum disorders have focused on these neurophysiological similarities. One such study asked participants to engage in a task believed to activate the prefrontal cortex and caudate nucleus of the brain so as to compare the performance of participants with OCD to that of those with anorexia. The study found that both groups had difficulty with the task and had higher cerebral glucose metabolism, suggesting a connection between the two disorders and offering evidence that, “ritualized obsessive and compulsive behavior (with reference to eating disorders, as well as washing and checking OCD) could have its origin within common neurobiological abnormalities,” (Murphy, et al. 2004). Although such results are clearly signs of progress, they are still indirect and speculative at best. More work is therefore needed in order to properly isolate the clinical symptoms, biochemical factors, and genetic causes behind OCD and eating disorders. In one of our studies we found that obsessive-compulsive overeaters responded to exposure and response prevention, while another group of overeaters responded better to more traditional stimulus control methods of treatment (Mount & Nezirogulu 1991). This shows that those eating disorders that are similar to OCD may respond better to treatment strategies used to treat more typical OCD behaviors. Consequently, for the sake of all those who suffer the obsessive-compulsive related disorders need to be studied further in order to enhance our understanding of their similarities and dissimilarities. In doing so we will hopefully not only arrive at better treatment strategies but also increase our knowledge of the psychological and biological mechanisms by which the disorders develop.

2004). Although such results are clearly signs of progress, they are still indirect and speculative at best. More work is therefore needed in order to properly isolate the clinical symptoms, biochemical factors, and genetic causes behind OCD and eating disorders. In one of our studies we found that obsessive-compulsive overeaters responded to exposure and response prevention, while another group of overeaters responded better to more traditional stimulus control methods of treatment (Mount & Nezirogulu 1991). This shows that those eating disorders that are similar to OCD may respond better to treatment strategies used to treat more typical OCD behaviors. Consequently, for the sake of all those who suffer the obsessive-compulsive related disorders need to be studied further in order to enhance our understanding of their similarities and dissimilarities. In doing so we will hopefully not only arrive at better treatment strategies but also increase our knowledge of the psychological and biological mechanisms by which the disorders develop.

Fugen Neziroglu, PhD, is a board certified Behavior and Cognitive psychologist involved in the research and treatment of OCD for 25 years. She is the Clinical Director of the Bio-Behavioral Institute in Great Neck, NY and Professor at Hofstra University.

Jonathan Sandler, BA is a research assistant at the Bio-Behavioral Institute in Great Neck, NY and he is involved in the research of Obsessive Compulsive Spectrum Disorders.

References

1. Kaye WH, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Barbarich N, Masters K, “Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa.” Am J Psychiatry, 2004; 161 2215-2221. 2. Yaryura-Tobias JA, & Neziroglu F (1983). “Obsessive Compulsive Disorders Pathogenesis Diagnosis and Treatment.” New York Marcel Dekker

3. Yaryura-Tobias JA, Pinto A Neziroglu F. ‘The integration of primary anorexia nervosa and obsessive-compulsive disorder.” Eating Weight Disorder Journal, 2001; 6 174-180. 4. Murphy R, Nutzinger DO, Paul T, Leplow B. “Conditional-Associative Learning in Eating Disorders: A Comparison With OCD.” J Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 2004; 26(2) 190-199.

4. Murphy R, Nutzinger DO, Paul T, Leplow B. “Conditional-Associative Learning in Eating Disorders: A Comparison With OCD.” J Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 2004; 26(2) 190-199.

5. Mount R, Neziroglu F, Taylor CJ. “An obsessive-compulsive view of obesity and its treatment.” J Clinical Psychology, Jan. 1990; 46 (1) 68-78.

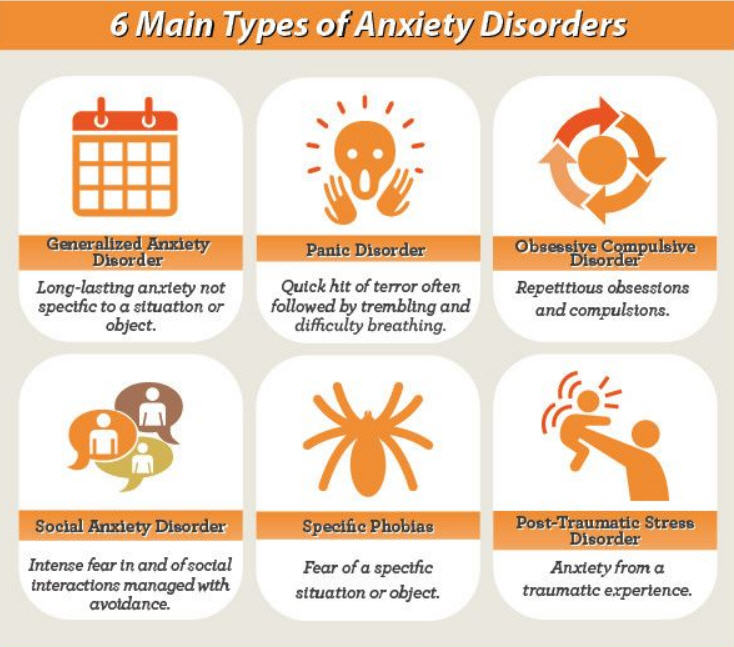

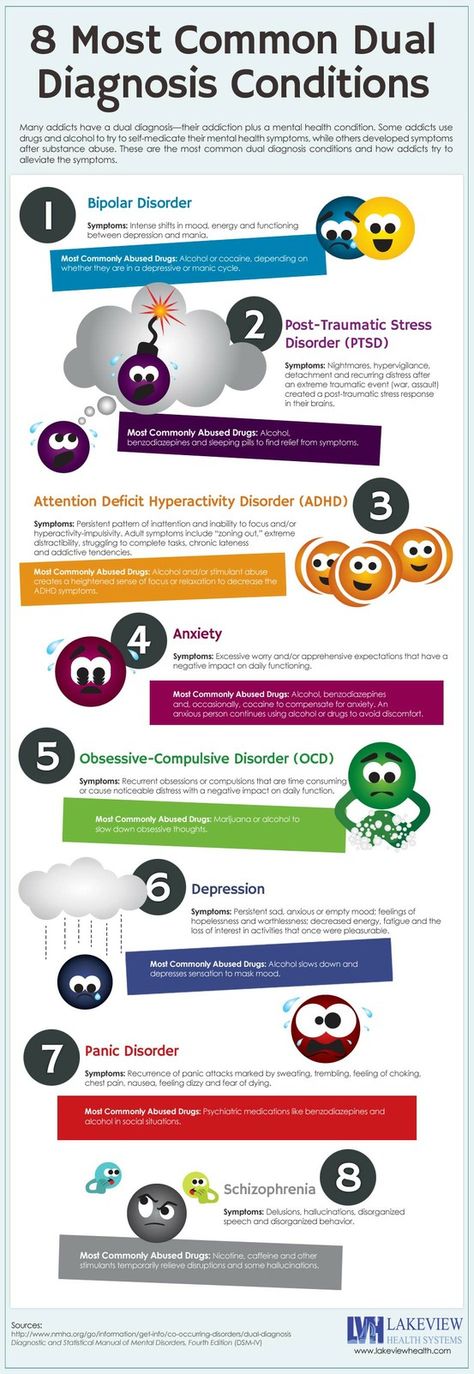

Eating Disorders and OCD: A Complicated Mix

Skip to contentEating disorders are sometimes characterized by obsessive, repetitive thoughts and compulsive, ritualistic behaviors. Statistics show that people with eating disorders are more vulnerable to co-morbid diagnoses such as anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Given some of the overlapping traits and features of eating disorders and OCD, treatment providers may struggle to differentiate the disorders. Similarly, clients may present with both disorders, distinct from one another. Understanding the similarities and differences between eating disorders and OCD can help providers develop a more comprehensive understanding of a client’s presentation and can also inform treatment interventions.

What is OCD and How Does It Compare to Eating Disorders?

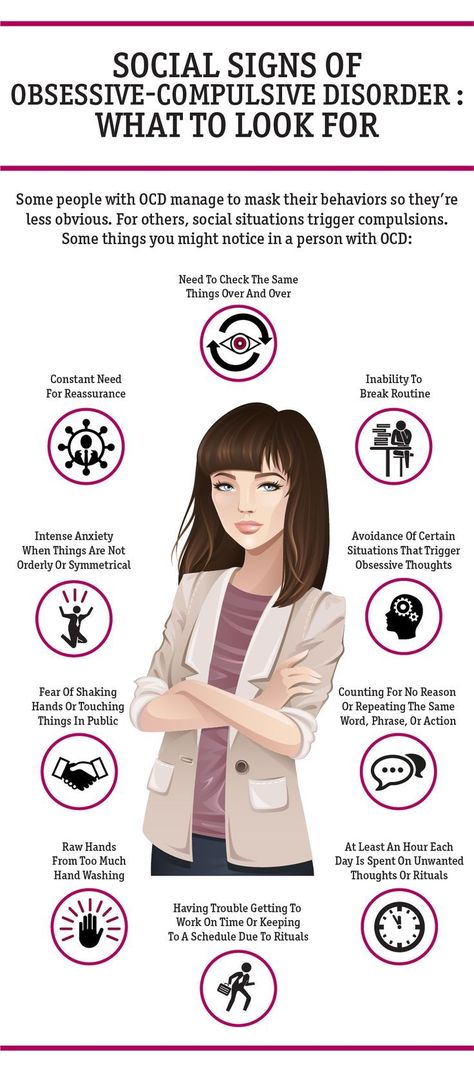

According to the DSM-5, obsessive-compulsive disorder is characterized by intrusive, repetitive thoughts that lead to compulsive behaviors. The compulsive behaviors are usually intended to alleviate the anxiety associated with the obsessions. The content of an individual’s obsessions and the specific compulsions they engage in can vary across presentations, and many cases of OCD look different from person to person.

As mentioned previously, eating disorders can consist of symptoms that characteristically are similar to the symptoms of OCD. Specifically, people with eating disorders can experience repetitive thoughts about food and body image and engage in ritualistic behaviors. Examples of common ritualistic behaviors in eating disorders include: body checking for any changes in shape and size, weighing self frequently to check for body changes, avoiding foods associated with fear of weight gain, and engaging in rituals around food intake, such as cutting food into tiny pieces or eating foods in a certain order.

An important distinction between OCD and eating disorders lies in the relationship that the individual has with their thoughts and actions. A person with OCD is typically in an ego-dystonic relationship with their thoughts and actions, meaning that they find the obsessions and compulsions in conflict with or aversive to their identity. In eating disorders, the relationship between the individual and their thoughts and actions typically is ego-syntonic, meaning that the person feels aligned with these thoughts and behaviors. This distinction can make a big difference in treatment. People with OCD are typically highly interested in ridding themselves of their thoughts and feelings whereas people with eating disorder may feel more tied to these components of their disorder since it feels like a part of their identity.

Co-Morbidity and Overlap

Treatment providers may see a variety of presentations with OCD when it co-occurs with an eating disorder. A typical presentation is one where an individual has both disorders, and the disorders are unrelated and mutually exclusive from one another. An example of this presentation would be a client with anorexia nervosa who also engages in ritualistic cleaning behaviors. In this example, the cleaning behaviors are completely unrelated to thoughts and feelings associated with the fear of weight gain and restricted food intake experienced in individuals with anorexia nervosa.

An example of this presentation would be a client with anorexia nervosa who also engages in ritualistic cleaning behaviors. In this example, the cleaning behaviors are completely unrelated to thoughts and feelings associated with the fear of weight gain and restricted food intake experienced in individuals with anorexia nervosa.

Another common presentation would be that the two disorders overlap. Specifically, the obsessions and compulsions observed in OCD are related to the symptoms of the eating disorder. An example of this presentation would be a client with anorexia who engages in ritualistic exercise. This individual may have difficulty interrupting the ritualistic exercise and may have to engage in certain repetitions before they can stop due to the compulsive nature of this behavior. In this example, the exercise rituals are closely related to the thoughts and feelings associated with the fear of weight gain observed in anorexia nervosa. This presentation can make it more difficult to differentiate between the disorders given the overlapping characteristics. Eating disorder practitioners who may struggle to see this distinction should consult with an OCD specialist when possible to establish proper diagnoses.

Eating disorder practitioners who may struggle to see this distinction should consult with an OCD specialist when possible to establish proper diagnoses.

Treatment

Because both eating disorders and OCD share overlapping diagnostic characteristics, treatment for both disorders will look similar. One intervention that exists across disorders is exposure therapy. Exposure therapy involves exposing the client to the feared stimulus in order to help them gradually build a tolerance to their fear and develop a new association to that stimulus. In eating disorder treatment, the clients are exposed to food. In OCD treatment, the clients are exposed to whatever fear their obsession takes with an emphasis on clients refraining from their compulsive behaviors. Treatment for a client with both an eating disorder and OCD would share the same emphasis on preventing the compulsive response. For instance, the client would not only be exposed to food but would be coached through refraining from any rituals around food in which they may compulsively engage.

One helpful intervention to use when doing exposure work is an exposure hierarchy. This intervention is designed to help the client and the practitioner identify the feared stimuli that the client will approach in treatment. An exposure hierarchy should build from the least triggering stimulus at the bottom to the most triggering stimulus at the top. Traditionally, exposure therapy involves working from the bottom of the hierarchy and building to the top as the client gradually habituates to the feared stimuli. This intervention is helpful for clients with eating disorders, clients with OCD, and clients with both disorders.

Cognitive treatment may vary across disorders. Most people with OCD realize that their obsessions are irrational but have difficulty coping with these thoughts. People with eating disorders tend to struggle more to see the distortions in their thinking. Therefore, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) – which includes identifying and challenging these cognitive distortions, may be more effective for people with eating disorders. Contrastingly, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which focuses more on changing a person’s relationship to their thoughts and feelings, would be more appropriate for a person with OCD who already can identify the distortions in their thoughts.

Contrastingly, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which focuses more on changing a person’s relationship to their thoughts and feelings, would be more appropriate for a person with OCD who already can identify the distortions in their thoughts.

Both eating disorder specialists and OCD specialists likely will see the overlap of these disorders in their work. Identifying the similarities, differences and interventions is an important aspect of treatment for either—or both—disorders.

####

Bethany Kregiel is a clinician in the adult residential program at Walden Behavioral Care, providing individual and group counseling to people with eating disorders. She received her Bachelor’s degree in Psychology from John Carroll University and her Master’s degree in Mental Health Counseling from Boston College. Bethany is particularly interested in working with individuals with eating disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and she incorporates aspects of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and exposure therapy into her work with her clients.

Let’s Connect

Notice: JavaScript is required for this content.

Compulsive overeating, psychological overeating, symptoms, signs

(Psychogenic overeating): SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

What is compulsive overeating? A person suffering from compulsive overeating, as a rule, begins to gain weight, and he is well aware that his habit regarding food consumption is abnormal. He seeks emotional comfort, trying to find it in eating food, which leads to obesity and related problems in society. nine0005

Compulsive overeating (psychogenic overeating): symptoms and signs

For a person suffering from compulsive overeating, words such as "just go on a diet" can be emotionally devastating, as it is not so much a matter of life support as an opportunity to cope with emotional stress.

People who suffer from compulsive overeating sometimes hide behind their appearance, using it as a shield against society - this is common among women survivors of sexual violence. She may feel guilty for not looking good enough (according to society's standards), ashamed for being overweight, and generally has very low self-esteem. Her constant overeating is an attempt to cope with these feelings, which, due to this addiction, only intensify, forming a vicious cycle that leads to even more dissatisfaction with herself and even more overeating. nine0005

She may feel guilty for not looking good enough (according to society's standards), ashamed for being overweight, and generally has very low self-esteem. Her constant overeating is an attempt to cope with these feelings, which, due to this addiction, only intensify, forming a vicious cycle that leads to even more dissatisfaction with herself and even more overeating. nine0005

Having low self-esteem and a burning need for love and approval, she may try to suppress these needs by spending money and overeating. Even when she really wants to stop eating a lot, she cannot cope with the disease without help. The inability to stop it, despite the potentially life-threatening consequences, is a sign of a pathological addiction that needs to be treated.

What are the signs and symptoms of compulsive overeating? nine0008

Signs and symptoms of compulsive overeating include:

- overeating or uncontrolled eating, even in the absence of physical hunger

- eating much faster than usual

- eating alone due to shame and embarrassment

- feelings of guilt due to overeating

- preoccupation with body weight

- depression or mood swings

- awareness that such a diet is abnormal

- cessation of all activity due to embarrassment due to being overweight

- unsuccessful attempts to use various diets

- eating a small amount of food in crowded places, but maintaining a large body weight

- a strong belief that life will be better when they can lose weight

- leaving food in strange places (closets, cupboards, suitcases, under the bed)

- indefinite or secretive diet

- self-abasement after eating

- strong belief that food is their only friend

- weight gain

- loss of sexual desire or promiscuity

- tiredness

an episode of binge eating, through vomiting, exercise, or taking laxatives.

Compulsive overeating risk

Compulsive overeating leads to emotional, psychological and physiological side effects that significantly reduce the quality of life and rob you of hope for the future.

When binge eaters consume excessive amounts of food, they often experience a feeling of euphoria, similar to that which occurs with drug use. They experience temporary relief from psychological stress and a distraction from feelings of sadness, shame, loneliness, anger, or fear. Researchers have suggested that this is due to abnormal endorphin metabolism in the brain. nine0005

In the case of compulsive overeating, eating causes the release of the neurotransmitter serotonin. This may be another sign of neurobiological factors contributing to addiction. Attempts to stop systematic overeating can lead to increased levels of depression and anxiety due to a decrease in serotonin levels.

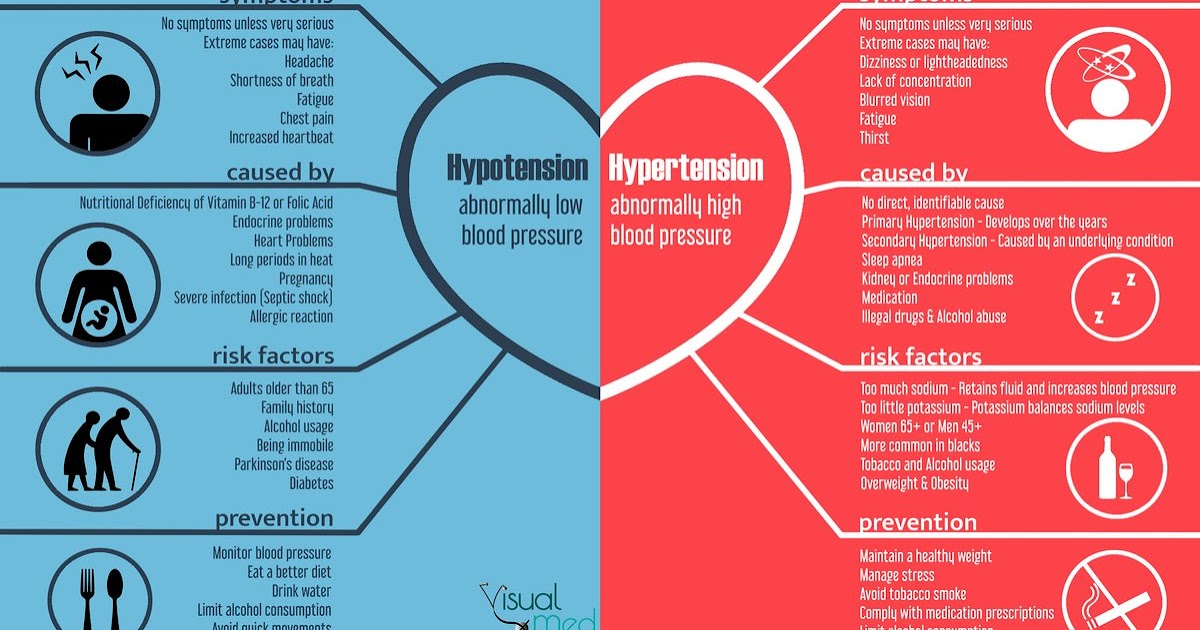

Left untreated, binge eating can lead to serious illnesses and conditions, including:

- High cholesterol

- Diabetes

- heart disease

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- APNOE of sleep (temporary respiratory suspension during sleep)

- Depression

- Arthritis

- Iznos of bone ostea

- Iznos Iznosa INST

What do you need to know?

Binge eating disorder is a very serious eating disorder, especially if it is accompanied by comorbid disorders such as bulimia nervosa, etc.

Binge eating disorder is a disease that can lead to irreversible complications, even death. If you are unsure whether you or a loved one has binge eating disorder, you should seek qualified medical attention to diagnose and prescribe appropriate treatment. You can also independently try to determine what type of disorder you or your loved one suffers, in which this material can help you. nine0005

Binge eating disorder is a disease that can lead to irreversible complications, even death. If you are unsure whether you or a loved one has binge eating disorder, you should seek qualified medical attention to diagnose and prescribe appropriate treatment. You can also independently try to determine what type of disorder you or your loved one suffers, in which this material can help you. nine0005 Eating disorder - compulsive overeating, treatment of psychogenic nervous overeating in Moscow

Everyone at least once got up from the table with a feeling of a full stomach. If this happens infrequently, then there is no cause for concern. If the episodes are repeated, or so you are trying to get rid of stress, bad mood, it is worth suspecting the development of a nervous eating disorder. Compulsive overeating, namely eating in uncontrollable sizes, repeated episodically. The disease often occurs against the background of mental disorders, sometimes contributes to gaining excess weight, obesity.

Therapy is carried out by a psychiatrist, interacting with a nutritionist, a psychologist. nine0005

Therapy is carried out by a psychiatrist, interacting with a nutritionist, a psychologist. nine0005 Article content:

- Disease description

- Symptoms

- Diagnostics

- Treatment

- Complications and advanced forms

Seek medical attention if symptoms occur. The information on the page is for reference only and cannot be used for self-diagnosis and self-treatment.

Nervous eating disorder - description of the disease

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illness, psychogenic overeating (hyperphagic stress response) is an independent disease that has a separate code 307.51. A patient with eating disorders is used to dealing with negative emotional stress, bouts of binge eating. The disease is manifested by a brutal appetite, which requires an abnormal amount of food with a high calorie content to satisfy it.

Serious factors (loss of a family member, injury) and minor reasons - a raised voice, a missed bus, etc. can provoke a nervous attack. Nervous eating disorder is caused by mental causes, there is no physiology in a causal relationship. Food in this case is a tonic that allows you to forget about the problem for a while, to relax. The patient, who has experienced a nervous shock, does not try to feed the stomach, but to drown out the feelings. nine0005

Serious factors (loss of a family member, injury) and minor reasons - a raised voice, a missed bus, etc. can provoke a nervous attack. Nervous eating disorder is caused by mental causes, there is no physiology in a causal relationship. Food in this case is a tonic that allows you to forget about the problem for a while, to relax. The patient, who has experienced a nervous shock, does not try to feed the stomach, but to drown out the feelings. nine0005 It is important to distinguish between physiological hunger and appetite of a nervous nature. This is an important step towards recovery, selection of treatment:

Nervous hunger Physical hunger May occur against the background of satiety, occurs unexpectedly and abruptly. Develops gradually, the body does not require urgent saturation. During attacks, the body requires unhealthy food - fast food, fatty foods, sweets, starchy foods, etc.  are in priority. nine0146

are in priority. nine0146 You can satisfy your appetite with any food, homemade and healthy food. The portion size is much larger than usual, there is no control over the amount eaten. A person eats exactly as much as needed to satisfy hunger. The portion size is much larger than usual, there is no control over the amount eaten. The physical need for food is disguised as a feeling of "sucking in the pit of the stomach", weakness. nine0146 Feelings of guilt and shame arise after eating. After eating, a feeling of satisfaction comes, strength appears. Mental disorders may be caused by genetics.

Compulsive eating disorder - symptoms

The basis of nervous overeating is the satisfaction of emotional needs, the solution of life problems, the ability to temporarily forget about loneliness, etc. However, food is a temporary salvation, after a short satisfaction comes a feeling of shame for weak willpower, guilt for the amount of food eaten.

Eating disorder symptoms are often confused with other eating disorders. The symptoms of bulimia echo the clinical picture of compulsive overeating. nine0005

Eating disorder symptoms are often confused with other eating disorders. The symptoms of bulimia echo the clinical picture of compulsive overeating. nine0005 An eating disorder or compulsive overeating is accompanied by the following symptoms:

- food becomes the only way to get rid of melancholy, sadness and other negative emotions;

- the ED patient prefers to eat alone, hiding his bouts of binge eating;

- lack of satiety after a sufficient amount of food consumed;

- stressful load causes regular overeating even in the absence of a physical need for food; nine0026

- a patient with eating disorders eats abnormally large portions in a short period of time;

- Gluttony aggravates during stress, emotional experiences.

The main manifestation of compulsive eating disorder is loss of control over appetite. Even with conscious overeating, a person cannot stop. A psychogenic disorder is more likely to affect people with an unstable psyche who take events to heart.

At risk are teenagers and women. Men also suffer from eating disorders, but much less frequently and, unlike women, do not seek to part with negative eating habits, taking them for granted. nine0005

At risk are teenagers and women. Men also suffer from eating disorders, but much less frequently and, unlike women, do not seek to part with negative eating habits, taking them for granted. nine0005 Diagnosis and treatment of psychogenic overeating

If you suspect nervous overeating, you should immediately seek help. You can make an appointment with a psychiatrist.

The Diagnostic and Static Manual of Mental Illness contains the following criteria, if 3 of them are met, the diagnosis of Eating Disorder - Binge Eating is confirmed:

- you prefer to eat alone;

- you experience discomfort from the amount of food eaten; nine0026

- you often sit down to eat when you don't feel hungry;

- after eating, guilt overcomes, self-loathing appears;

- regardless of the size of the portion you eat quickly, the food is not chewed thoroughly.

The doctor performs a control weighing, finds out what the patient's weight was in the recent past, how quickly the figure on the scales has changed.

Then he selects the tactics of treatment in accordance with the anamnesis.

Then he selects the tactics of treatment in accordance with the anamnesis. Treatment

Therapy of patients suffering from nervous overeating should be complex. Eating disorders are treated by a psychiatrist, psychotherapist, psychologist, nutritionist. The family doctor in this situation is not competent due to the lack of necessary knowledge and experience in the treatment of ED.

"CIRP" specializes in the study, treatment of ED and adheres to complex tactics:

- drug therapy;

- psychotherapy effective for eating disorders; nine0026

- power restoration.

In the course of psychotherapy, individual and group methods are used, the main task of which is setting the right goals, teaching self-control, developing incentives, healthy beliefs.

Read more in the article:

Compulsive overeating: advice from a psychotherapistMuch attention in the treatment of eating disorders is given to nutrition, sometimes hospitalization is recommended.

The clinic has created comfortable conditions for the treatment of patients, if necessary, emergency medical care is provided, an intensive care unit is provided. Usually, binge eating is treated on an outpatient basis. At first, support and control of loved ones at home is recommended. nine0005

The clinic has created comfortable conditions for the treatment of patients, if necessary, emergency medical care is provided, an intensive care unit is provided. Usually, binge eating is treated on an outpatient basis. At first, support and control of loved ones at home is recommended. nine0005 To book an appointment with the Center for the Study of Eating Disorders in Moscow, call +7(499) 703-20-51 or use the online form.

Complications and advanced forms

An eating disorder (overeating) is fraught with the development of serious consequences - obesity and atherosclerosis. The patient experiences chronic emotional dissatisfaction, which leads to prolonged depression and causes suicidal thoughts.

Unless treated for destructive binge, there is a high risk of complications:

- Distance from relatives and family as the condition worsens, refusal of family dinners and friendly meetings. A person with eating disorders prefers a secluded lifestyle to hide behavioral deviations.

- Often a depressive state becomes the cause of addiction to alcohol and drugs. So the patient with ED tries to compensate for dissatisfaction with life.

- Compulsive nervous overeating affects health. Common complications include obesity, arthritis, high cholesterol, hypertension, and heart and kidney failure. The liver, gastrointestinal tract suffer from excessive uncontrolled nutrition, the character changes for the worse - irritability and anger prevail. nine0026

- Given the severity of complications, you should not postpone a visit to the doctor and self-medicate. Subject to timely treatment, the prognosis of therapy for compulsive disorder is favorable.

Make an appointment in Moscow by calling +7(499) 703-20-51 or fill out the online form.

Author: Sineutskaya Ekaterina Olegovna

Head of the inpatient department of the Center for Institutional Research,

psychiatrist, psychotherapist, narcologist.