Mental illness and gun violence

Mental Illness and Gun Violence - The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence

Background

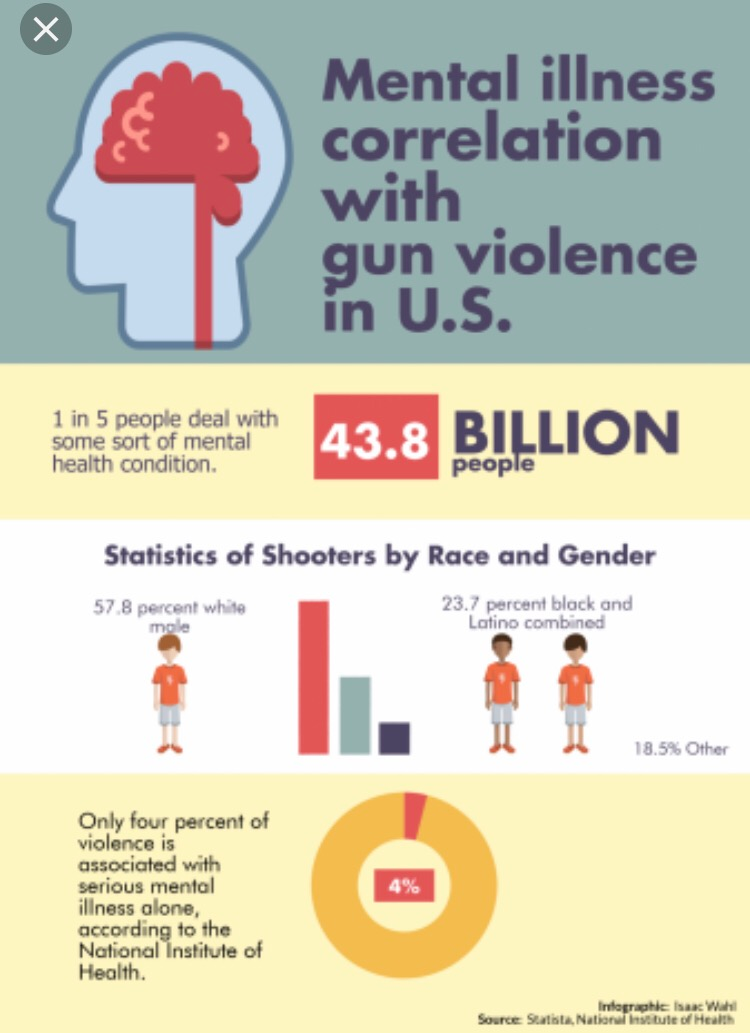

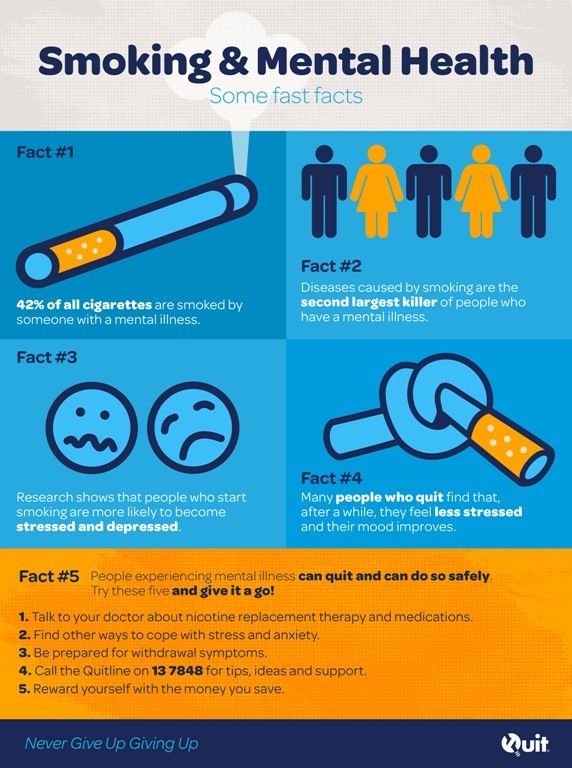

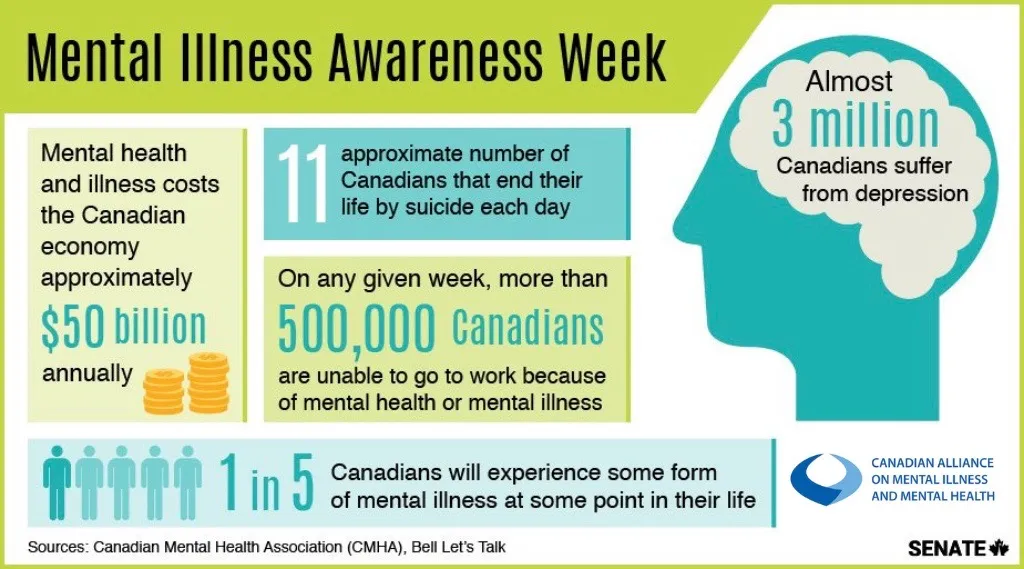

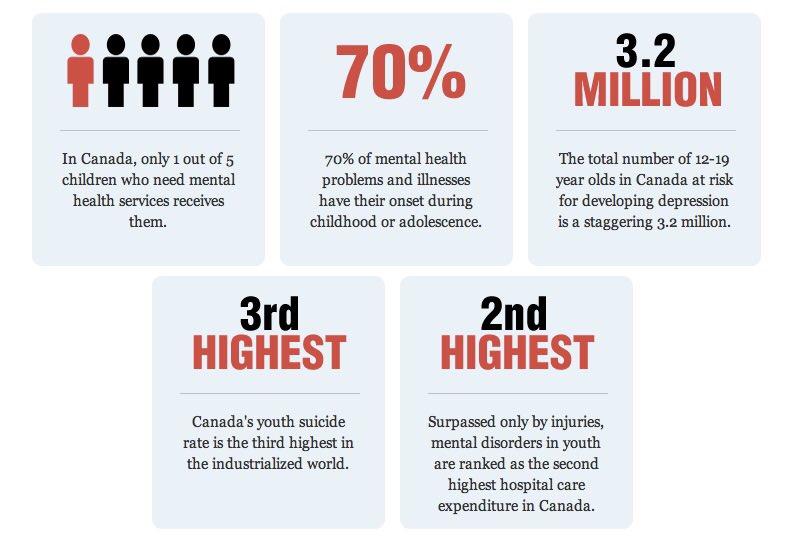

Many Americans live with mental illness. Indeed, around one in five Americans (43.4 million) have a diagnosed mental illness in a given year and one in 25 Americans (9.8 million) have a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.1

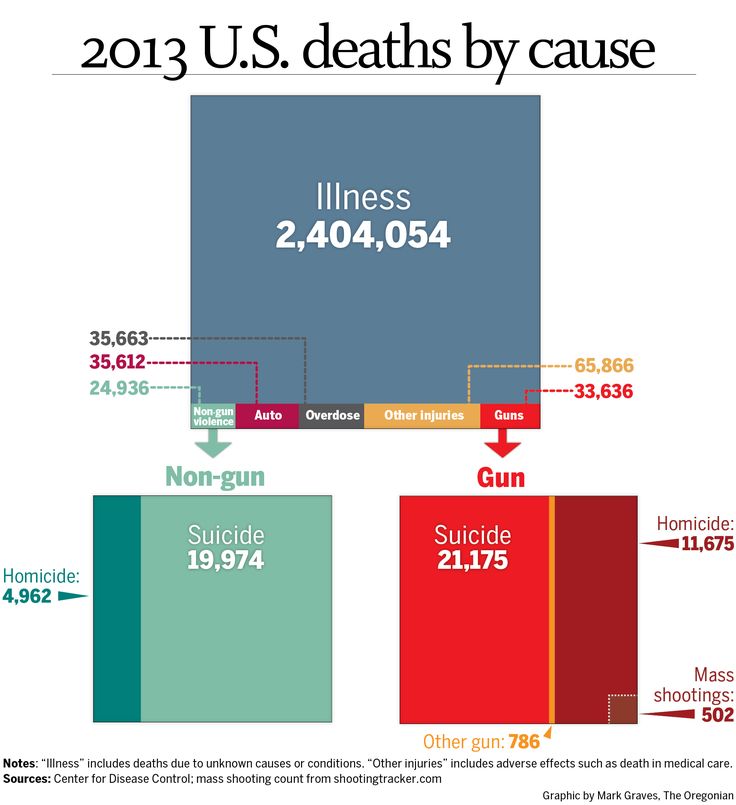

It is critical to understand that mental illness is not the cause of gun violence. The United States has similar rates of mental illness to other countries but much higher rates of gun violence.2,3 The firearm homicide rate in the U.S. is nearly 25 times higher than other high-income countries and the firearm suicide rate is nearly 10 times that of other high-income countries. Overall rates of gun deaths are 11.4 times higher in the U.S. as compared to other high-income countries.4

Violence has many contributing risk factors and mental illness alone is very rarely the cause. Only 4% of interpersonal violence in the United States is solely attributable to mental illness. 5 Indeed, people with mental illness are more likely to be victims of interpersonal violence than perpetrators of violence.6 Similarly, there is no one single cause of suicide. While mental illness, specifically depression, is a risk factor for suicide, not everyone who experiences suicidality or dies by suicide has a mental illness. It is estimated that more than half of all suicide decedents did not have a known mental health diagnosis at the time of their death.7 People who die by firearm suicide are even less likely to have a diagnosis.8 Research also has found that mental illness is only weakly correlated with suicidal thoughts and behavior.9

Gun violence prevention policies that focus solely on a mental health diagnosis will not stop gun violence. Instead, these policies fuel prejudice and fear around people living with a mental illness and could lead to people avoiding mental health services.

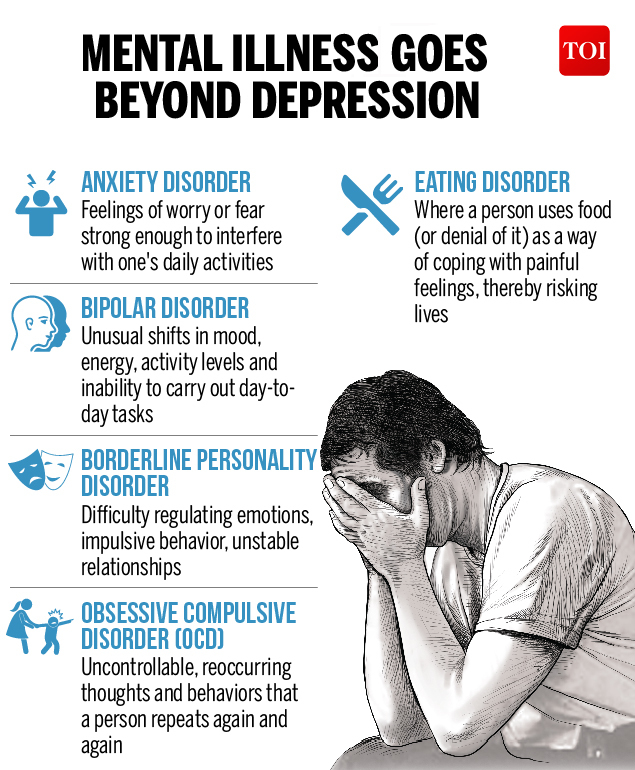

What is mental illness?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines mental illnesses as “conditions that affect a person’s thinking, feeling, mood, or behavior. ”18

”18

What is serious mental illness?

The CDC defines serious mental illness as “a mental illness or disorder with serious functional impairment that substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities.”19

Interpersonal Violence And Mental Illness

After mass shootings and other widely publicized shootings, people often blame mental illness as the cause of gun violence. It is common to read reports that describe the shooter as “psychotic” or “mentally disturbed.” These shootings capture the public’s attention and reinforce the harmful myth that mental illness causes violent behavior.

We know that is not the case.

Research consistently shows that the majority of people living with mental illness, including those with serious mental illness, are not violent towards others.20,21 In fact, people with mental illness are more likely to be victims of interpersonal violence than perpetrators.22

There are certain times, in certain settings, when small sub-groups of people with serious mental illness are at elevated risk of violence, such as the period surrounding a psychiatric hospitalization or first episode of psychosis. 23,24 Still, only a very small proportion of interpersonal violence in the United States – about 4% – is attributable to mental illness alone.25 This means that if we were to somehow “cure” mental illness nationwide, we would still be left with 96% of interpersonal violence.

23,24 Still, only a very small proportion of interpersonal violence in the United States – about 4% – is attributable to mental illness alone.25 This means that if we were to somehow “cure” mental illness nationwide, we would still be left with 96% of interpersonal violence.

Attributable Risk of Violent Behavior Toward Others

Other risk factors96%

Serious mental illness4%

Source: Swanson JW, McGinty EE, Fazel S, & Mays VM. (2014). Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: Bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Annals of Epidemiology.

Unfortunately, we continue to see policy proposals for firearm restrictions based on mental illness diagnoses. Policies that restrict access to guns based solely on diagnosis are not only stigmatizing, but will not significantly reduce overall rates of gun violence in the United States.26,27

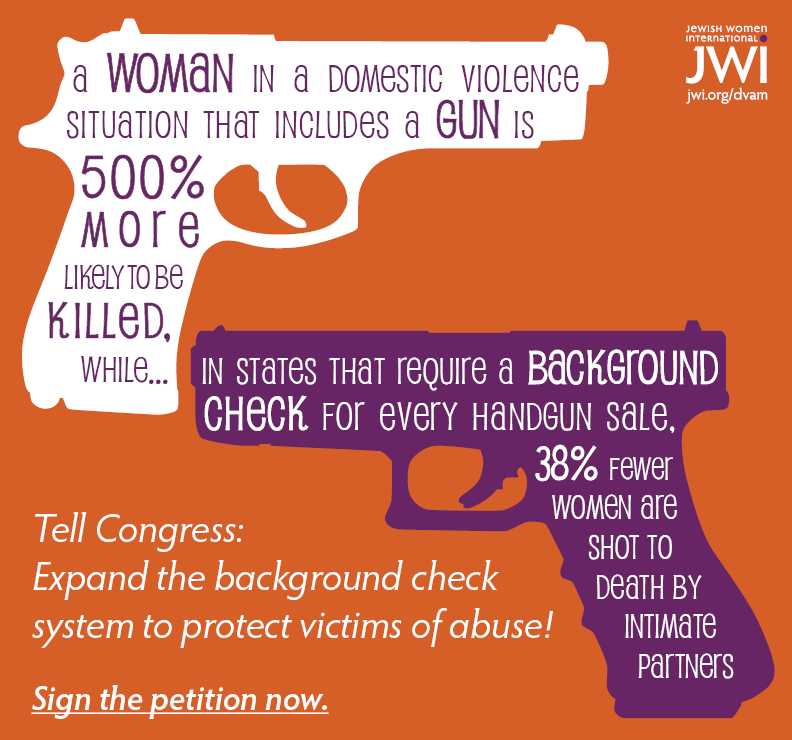

Instead of focusing on mental illness, policies and programs to reduce gun violence should focus on evidence-based, behavioral risk factors for future violence, such as past violent behavior,28 domestic violence,29 risky substance use,30,31 and risky alcohol use. 32 Other risk factors for violence related to life experiences, personality, and identity that can be helpful markers for support and prevention programs include exposure to violence,33 being male,34 being young,35 and impulsive anger.36

32 Other risk factors for violence related to life experiences, personality, and identity that can be helpful markers for support and prevention programs include exposure to violence,33 being male,34 being young,35 and impulsive anger.36

“The terms we hear from people on both sides of the aisle, such as ‘the dangerously mentally ill,’ are misleading, damaging to the mental health community, and not based on evidence. The gun lobby, politicians, and the ill-informed media have conditioned us to associate mental illness with violence. The idea that mentally ill means violent is an alternative fact. Period.”

- Josh Horwitz, Executive Director

Suicide And Mental Illness

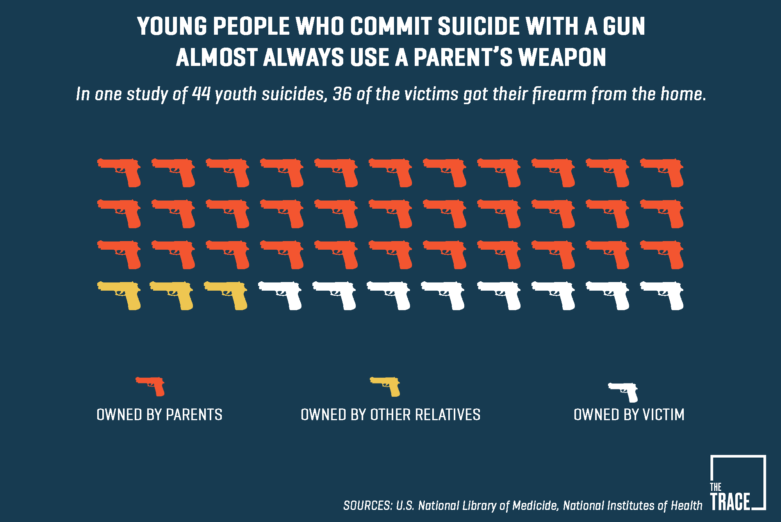

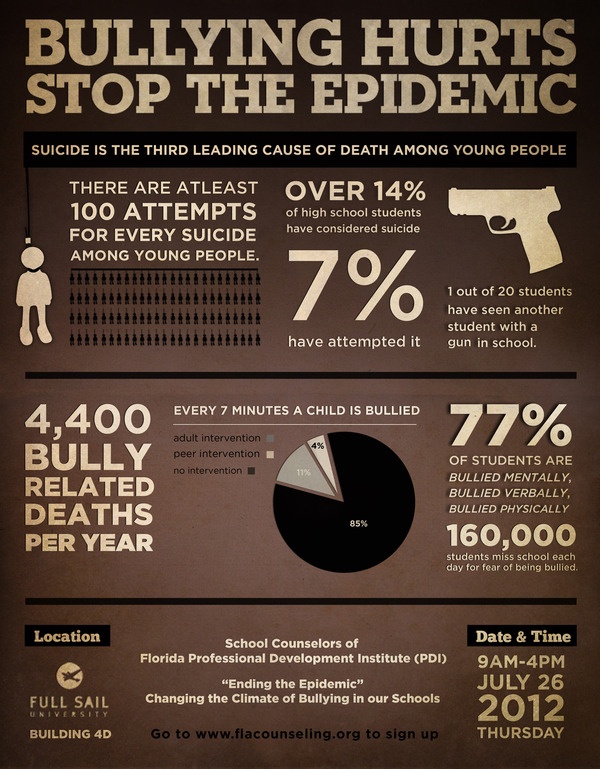

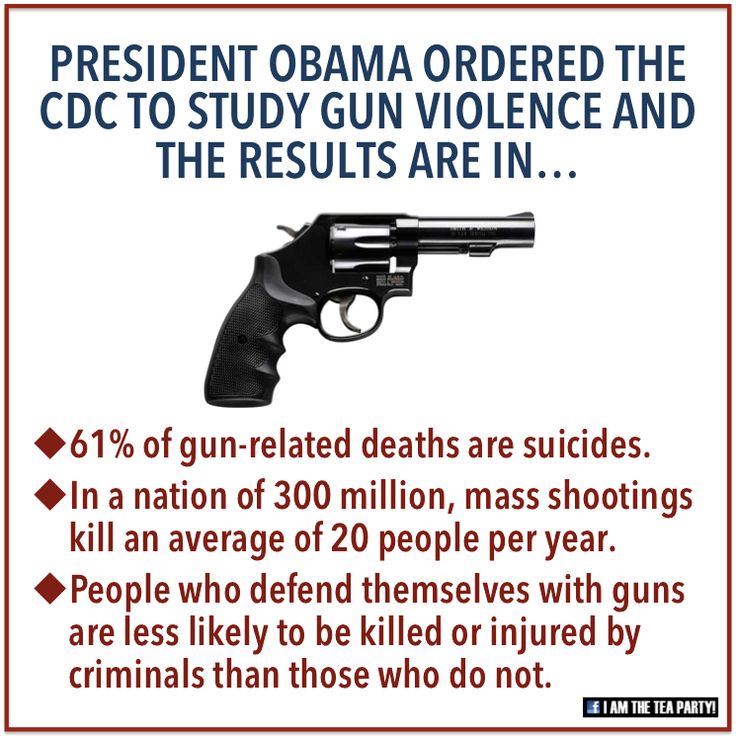

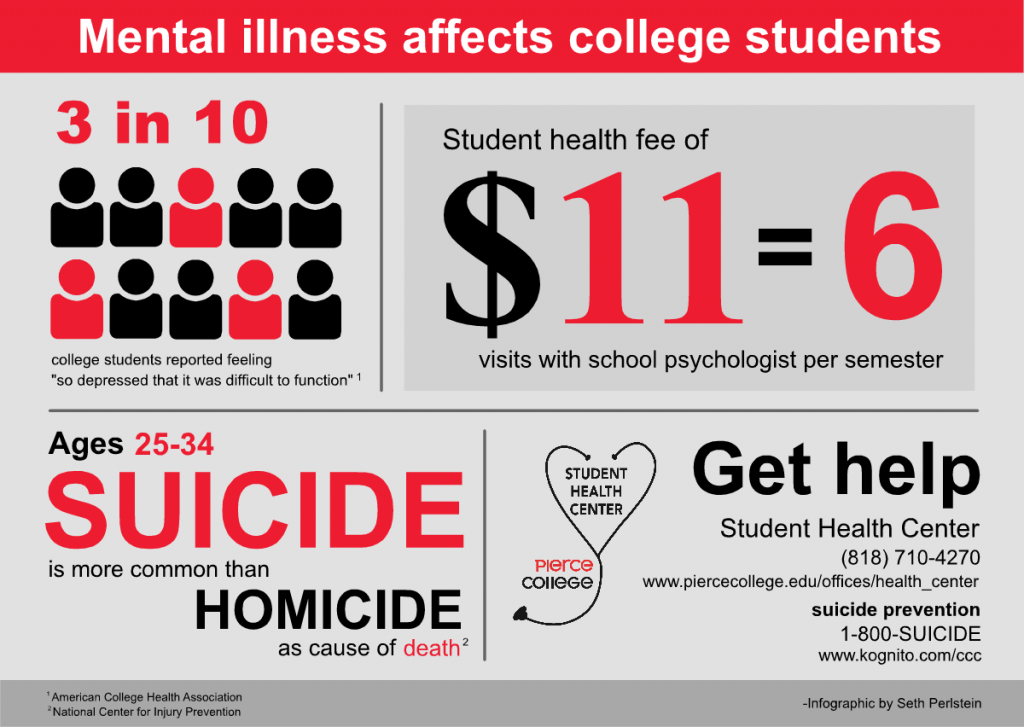

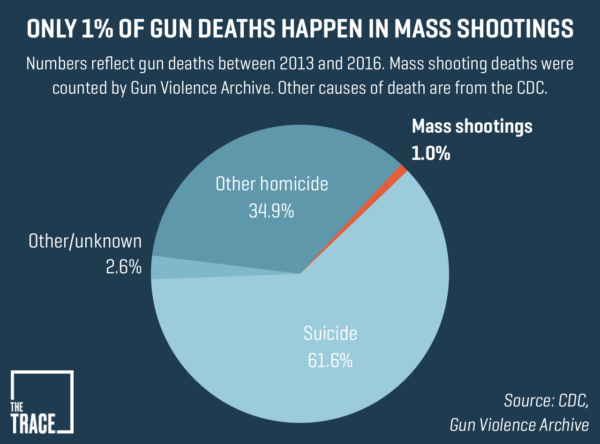

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among young adults aged 25-34, and the 10th leading cause of death among all Americans.37 Making up three-fifths of gun deaths, suicide is a major contributor to the gun violence epidemic.38

There is no one single cause of suicide, and while mental illness is a risk factor for suicide, not everyone who is experiencing suicidality or dies by suicide has a mental illness. In fact, mental illness is only weakly correlated with suicidal thoughts and behavior.39,40 It is estimated that more than half of all suicide decedents did not have a known mental health diagnosis at the time of their death and that firearm suicide decedents were even less likely to have a diagnosis.41 As such, the mental health system alone is not an effective pathway for preventing firearm suicide.42 There is research to support the idea that, overall, access to more behavioral health treatment only has a small protective effect on the rate of firearm suicide.43

In fact, mental illness is only weakly correlated with suicidal thoughts and behavior.39,40 It is estimated that more than half of all suicide decedents did not have a known mental health diagnosis at the time of their death and that firearm suicide decedents were even less likely to have a diagnosis.41 As such, the mental health system alone is not an effective pathway for preventing firearm suicide.42 There is research to support the idea that, overall, access to more behavioral health treatment only has a small protective effect on the rate of firearm suicide.43

Suicide Decedents with Mental Health Conditions

Did have a known mental health condition46%

Did not have a known mental health condition54%

Source: Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, Kegler SR, Yuan K, et al. (2018). Vital Signs: Trends in state suicide rates — United States, 1999–2016 and circumstances contributing to suicide — 27 states, 2015. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report.

Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report.

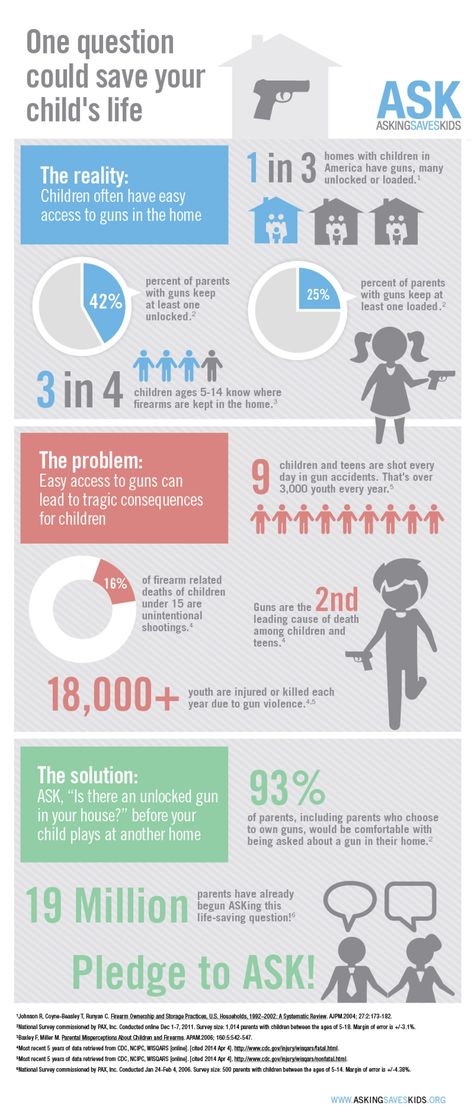

Additionally, suicidal thoughts and behaviors often fluctuate over time. They are often prompted by difficult life situations which themselves may change over time. Such life stressors include relationship problems or rejection, financial and housing instability, criminal/legal troubles, death of a loved one, serious illness, trauma, physical or sexual abuse, family violence or distress/dysfunction, persecution, and other recent or impending crises. Impulsive or aggressive tendencies, risky alcohol or substance use, and easy access to lethal methods, such as firearms, also increase suicidal risk.44

Indeed, many research studies have shown that easy access to guns increases risk of suicide.45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61

Ensuring that someone doesn’t have access to a firearm during a potential suicidal crisis, regardless of mental illness, can often be the difference between life and death.

Preventing suicide is an important part of gun violence prevention. However, focusing only on mental illness is not sufficient to prevent these deaths. To effectively prevent suicide, we must reduce easy access to guns, especially during periods of elevated risk.

However, focusing only on mental illness is not sufficient to prevent these deaths. To effectively prevent suicide, we must reduce easy access to guns, especially during periods of elevated risk.

Prevent Firearm Suicide

Prevent Firearm Suicide is a project of the Ed Fund that was developed to raise awareness about how temporarily reducing access to firearms during periods of high risk for suicide is life-saving. PreventFirearmSuicide.com shares effective, evidence-based interventions for firearm suicide prevention; information on the intersection of firearms and suicide including risk factors and statistics; state-level firearm suicide for all 50 states; and includes a robust resource library of educational materials, initiatives, research, and other resources about firearm suicide prevention and means safety. To learn more, please visit PreventFirearmSuicide.com and our page on firearm suicide.

Focusing on mental illness is problematic for gun violence prevention

Gun violence prevention policies that focus solely on a mental illness diagnosis will not stop gun violence and, instead, could fuel prejudice and fear around people living with a mental illness and may lead to people avoiding mental health services. We must dispel the myth that living with a mental illness makes you dangerous and likely to perpetrate violence towards others.

We must dispel the myth that living with a mental illness makes you dangerous and likely to perpetrate violence towards others.

HATE IS NOT A MENTAL ILLNESS

Evidence shows that narratives surrounding shootings are different based on the race of the shooter. An analysis of 219 mass shootings and subsequent news coverage found that the shooters’ race strongly predicted whether the media discussed the shooters’ mental health.63 When a mass shooting was carried out by a White or Latino person, the media often attributed it to mental illness. White shooters, in particular, were framed as good people suffering from extreme life circumstances and were 19 times more likely to be framed as suffering from mental illness compared to Black shooters. Black and Latino perpetrators were more often portrayed as ongoing threats to public safety, while White perpetrators were viewed more sympathetically, putting the blame on mental illness and not on the individuals themselves.65

We know that hate is not a mental illness. We know that changing the narrative after a mass shooting based on the skin color of the perpetrator is both dangerous and factually incorrect. And yet, time and time again, the media is quick to call something “terrorism” if the perpetrator was Black, and quick to blame mental illness when the perpetrator was White.64,65

We know that changing the narrative after a mass shooting based on the skin color of the perpetrator is both dangerous and factually incorrect. And yet, time and time again, the media is quick to call something “terrorism” if the perpetrator was Black, and quick to blame mental illness when the perpetrator was White.64,65

“Most of the time, mass shooters aren’t driven by delusions or voices in their head. They are driven by a need to wield their power over another group. They are angry at the perceived injustices that have befallen them at the hands of others — women who wouldn’t sleep with them, fellow students who didn’t appreciate their talents, minorities enjoying rights that were once only the privilege of white men like them. It’s not an altered perception of reality that drives them; it’s entitlement, insecurity, and hatred. Maybe some of them also have depression, ADHD, or anxiety, but that is not why they opened fire on a group of strangers.”

- Amy Barnhorst, Vice Chair for Community Mental Health in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, Davis and member of the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy

Stop the Stigma

When the media, politicians, or other public figures blame a shooter’s behavior on mental illness, they are stigmatizing and discriminating against the millions of Americans living with mental illness. Terms such as “the dangerously mentally ill” are misleading, disparaging, and not based on evidence.

Terms such as “the dangerously mentally ill” are misleading, disparaging, and not based on evidence.

The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence works to ensure that our messaging and policy recommendations do not stigmatize those living with mental illness. We know that mental illness diagnoses do not define people, and mental illness is not a choice. We can’t choose where we come from, we can’t choose what we look like, and we can’t choose whether or not to have a mental illness.

The way we talk about gun violence — and the laws that we support — should be based on facts, not falsehoods. To be effective, we must focus on dangerous behaviors — not diagnoses. By focusing on dangerous behaviors as established by research, we can make gun violence — including gun suicide — rare and abnormal.

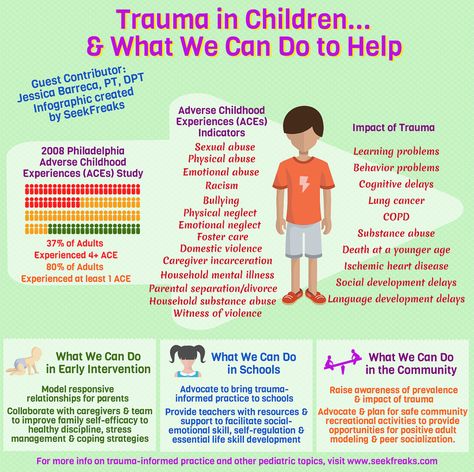

Mental Health Consequences of Gun Violence

While the evidence is clear that mental illness is not the cause of gun violence, incidents of gun violence may cause mental health difficulties for survivors of gun violence. Mental health effects following gun violence may include depression, anxiety, trauma, post traumatic stress disorder, intrusive thoughts, sleep problems, and personality changes.66 Additionally, the trauma of gun violence can ripple out into the community, far beyond those who were shot or injured. Family members, friends, neighborhoods, communities, first responders, and health care providers may all experience adverse mental health effects.

Mental health effects following gun violence may include depression, anxiety, trauma, post traumatic stress disorder, intrusive thoughts, sleep problems, and personality changes.66 Additionally, the trauma of gun violence can ripple out into the community, far beyond those who were shot or injured. Family members, friends, neighborhoods, communities, first responders, and health care providers may all experience adverse mental health effects.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Focus gun violence prevention policies on evidence-based risk factors — not mental illness. Use appropriate language and avoid harmful stereotypes.

Mental illness does not cause gun violence. Gun violence prevention policies should be evidence-based, promote public safety, and respect individuals with mental illness.

Firearm removal laws, like extreme risk protection orders, should not be based on a mental health diagnosis and should be based on risk factors for violence and overall dangerousness, like a history of violent behavior, domestic violence, and risky alcohol use.

The language we use when talking about mental illness should be judgment free and not reinforce stereotypes or negative beliefs.

How to talk about mental illness without the stigma:

| Problematic | Preferred |

|---|---|

| Mentally ill, mental defective | Person with mental illness |

| Person-first language is preferred. A diagnosis does not define an individual. | |

| Dangerously mentally ill | Person with serious (severe) mental illness |

| The word “dangerous” is stigmatizing, not based on facts, and not a clinical word. No person is dangerous purely because they have a serious mental illness. | |

Resources

Fact sheets

- Mental Illness and Guns

- Guns, Public Health and Mental Illness

Reports

- Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy: Guns, Public Health, and Mental Illness: An Evidence-Based Approach for Federal Policy

- Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy: Guns, Public Health, and Mental Illness: An Evidence-Based Approach for State Policy

Read More

- May 2019 Q&A, In My Voice: For Years, I Equated Mental Illness with Violence.

I Was Wrong

I Was Wrong - May 2019 Q&A, In My Voice: I Experienced Gun Violence Firsthand and Struggled with My Mental Health. Now I’m Working to Help Others Address Both

- May 2019 Q&A, In My Voice: Seeking Help and Navigating Discrimination as a Black, Female Therapist

- May 2019 Q&A, In My Voice: Decoupling Mental Illness and Violence as a Psychiatrist

- May 2019 blog, Recovering, Not Recovered

- March 2019 blog, It’s Time to Retire the Term “Red Flag Laws”

- January 2019 roundtable, Guns, Suicide, and Mental Illness: A Roundtable Discussion

- October 2018 blog, Don’t Call Us Dangerous. Don’t Call Us “the Mentally Ill”

- September 2018 blog, Six phrases that stigmatize suicide and mental illness

- September 2018 article in Channel 3000, Officials Warn Not to Jump to Conclusion that Middleton Shooting is Related to Mental Health

- May 2018 article in The Advocate, Why Didn’t Bizarre Behavior Block Man Accused in Lafayette Police Officer’s Death From Buying a Gun?

- March 2018 article in the New Yorker, A Glimmer of Hope in the Political Impasse on Gun Control

- February 2017 op-ed in the Huffington Post, We Can Stop Gun Violence Without Blaming People Living With Mental Illness

Research

- Appelbaum P & Swanson J.

(2010). Law & psychiatry: gun laws and mental illness: how sensible are the current restrictions? Psychiatric Services.

(2010). Law & psychiatry: gun laws and mental illness: how sensible are the current restrictions? Psychiatric Services. - Choe JY, Teplin LA, & Abram KM. (2008). Perpetration of violence, violent victimization, and severe mental illness: balancing public health concerns. Psychiatric Services.

- Elbogen EB & Johnson SC. (2009). The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry.

- Lu Y & Temple JR. (2019). Dangerous weapons or dangerous people? The temporal associations between gun violence and mental health. Preventive Medicine.

- McGinty EE, Webster DW, & Barry CL. (2013). Gun policy and serious mental illness: Priorities for future research and policy. Psychiatric Services.

- Metzl JM & MacLeish KT. (2015). Mental illness, mass shootings, and the politics of American firearms.

American Journal of Public Health.

American Journal of Public Health. - Pescosolido BA, Manago B, & Monahan J. (2019). Evolving public views on the likelihood of violence from people with mental illness: Stigma and its consequences. Health Affairs.

- Swanson JW, Roberston AG, Frisman LK, Norko MA, Lin HJ, Swartz MS, & Cook PJ. (2013). Preventing gun violence involving people with serious mental illness. Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis.

- Swanson, JW, McGinty EE, Fazel S, & Mays VM. (2015). Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Annals of Epidemiology.

- Van Dorn R, Volavka J, & Johnson N. (2012). Mental disorder and violence: is there a relationship beyond substance use? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology.

Additional Resources

- American Psychological Association’s gun violence prevention resources

- Autistic Self Advocacy Network's “Make Real Change On Gun Violence: Stop Scapegoating People With Mental Health Disabilities”

- Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law's “Wrong Focus: Mental Health in the Gun Safety Debate”

- Coalition for Smart Safety and the Consortium for Citizens with Disabilities Rights Task Force's Debunking the Myths: Mental Health and Gun Violence

- Mental Health America’s “Position Statement 72: Violence: Community Mental Health Response”

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)'s resources on Extreme Risk Protection Orders

- National Council of Behavioral Health

If you or someone you know needs some support now, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or text “HOME” to 741-741.

Last updated July 2020

It’s tempting to say gun violence is about mental illness. The truth is much more complex.

- Viewpoints

Focusing on mental illness as the cause of mass shootings diverts attention from the larger problem of gun violence in the U.S., two experts argue. It also distracts people from the real issue when it comes to guns and mental health: suicide.

Editor’s note: The opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the AAMC or its members.

The scale of gun violence in the United States lends itself to astonishing comparisons.

Our nation’s firearm-related civilian death toll over the past 50 years exceeds the number of soldiers who perished in combat in all our wars combined. More American children and young adults died from firearm injuries in 2020 than from any other cause. In recent years, our rate of gun homicides has been 25 times higher than that of comparable nations. And if we were to inscribe on a granite wall the names of all those lost to firearm violence in the past two decades, we would need a monument 12 times larger than the Vietnam War Memorial.

And if we were to inscribe on a granite wall the names of all those lost to firearm violence in the past two decades, we would need a monument 12 times larger than the Vietnam War Memorial.

The absolute numbers are equally sobering.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, an estimated 2.5 million people have been injured in gunfire in the United States, and 750,000 of them have died. Although we grow increasingly accustomed to random shooting rampages — a uniquely American recurring nightmare — on the day of any such shooting in 2020, an average of 134 other people died from firearm injuries. More than half those deaths were suicides; others were gang shootings, domestic violence incidents, or arguments gone bad between intoxicated young men. The U.S. gun homicide rate increased by 33% in 2020.

Each of these data points represents a life cut short, a heartbreaking story that adds to the unabated drip, drip, drip of gun violence in America.

Fourteen-year-old Eric died while walking home from school in a crime-burdened neighborhood in San Diego, shot by one of five other teenagers, allegedly gang members. Across town in a middle-class suburb, a highly intoxicated man named Daniel fatally shot the boyfriend of his estranged wife, and then shot himself. In a hospital in Tulsa, a surgeon named Preston died when a former patient shot him and three other people with an AR-15 rifle. A young Iraq war veteran named Tony, diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder and struggling through a divorce, called his mother on Christmas to say, “Don’t ever forget how much I love you” before shooting himself.

Across town in a middle-class suburb, a highly intoxicated man named Daniel fatally shot the boyfriend of his estranged wife, and then shot himself. In a hospital in Tulsa, a surgeon named Preston died when a former patient shot him and three other people with an AR-15 rifle. A young Iraq war veteran named Tony, diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder and struggling through a divorce, called his mother on Christmas to say, “Don’t ever forget how much I love you” before shooting himself.

“Why would anyone kill all those innocent people?” That’s the natural question when we learn of yet another senseless gun massacre against strangers in a public place.

In a diverse nation with more guns than people and a constitutionally protected right to bear arms, the complex mix of circumstances and cultural forces that fuel gun violence pose daunting challenges for those who hope to understand and address it.

What’s going on?

“Why would anyone kill all those innocent people?” That’s the natural question when we learn of yet another senseless gun massacre against strangers in a public place.

The answer we often hear is “mental illness,” an explanation that fits the common perception that people with serious mental illnesses are dangerous. But most violence, including lethal and near-lethal violence, is not causally linked to mental illness.

Mental illness is quite common in the United States. In 2020, approximately 20% of U.S. adults — 53 million people — met criteria for at least one psychiatric diagnosis in the previous year, and nearly 6% — 14 million individuals — had a serious, impairing mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression. Given that so many individuals have a mental health diagnosis and the large majority of those individuals are never violent, psychiatric illness is too blunt an instrument to serve as a useful indicator of violence risk.

Indeed, if serious mental illnesses suddenly disappeared, violence would decrease by only about 4%. More than 90% of violent incidents, including homicides, would still occur.

Even mass shooters, who might seem most likely to be driven by mental illness, don’t necessarily suffer from major psychiatric disorders. Arguably one of the best such reports on the topic, conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, found that only 25% of such assailants had a diagnosed mental illness. Although it is difficult to obtain precise data on the gun-prohibited status of every mass shooter, less than 5% of these individuals had a record of a gun-disqualifying mental health adjudication, such as an involuntary commitment to a mental health facility.

Meanwhile, “Why did he kill all those people?” is so compelling a question that it seems to demand an answer. If mental illness isn’t usually the cause, what is? The honest response from science is that we don’t know all that much. Sometimes, a stew of alienation and resentful anger directed against a dehumanized “other” is at play. In rare instances, acute psychotic symptoms such as paranoid delusions contribute. In addition, crisis, trauma, and significant personal loss are common to some assailants, but those factors ultimately reveal little since they are shared by many people who never engage in a mass shooting.

In addition, crisis, trauma, and significant personal loss are common to some assailants, but those factors ultimately reveal little since they are shared by many people who never engage in a mass shooting.

The real story — and the real need — regarding mental illness and violence is suicide. Not only are most firearm deaths suicides, but most suicides are causally linked to mental illness.

Given these realities, erroneously placing mental illness at the center of the American gun violence narrative stymies solutions to both these public health problems, which come together only on their edges.

Associating mental illness with violence reinforces stigma and unwarranted fear of people with mental illnesses — people who need support to recover from serious brain-based conditions. In addition, some mental health advocates may understandably be tempted to focus on violence in the quest for crucial funding of services, but making such a case can lead to misaligned priorities, misdirected resources, and misapplied coercive interventions against people with mental illnesses.

The real story — and the real need — regarding mental illness and violence is suicide. Not only are most firearm deaths suicides, but most suicides are causally linked to mental illness.

Even when we look at suicide, though, the relationship between mental illness and risk is complex and nuanced. For example, there are important gender differences in the role of both mental illness and firearms in suicide. Extensive research on suicide risk factors suggests that mental illness is implicated in about 7 out of 10 suicides among women, but only about half of men who die by suicide. Social and economic stressors are stronger determinants of suicidality among men, who are also significantly more likely than women to use a firearm in a suicide.

Despite such complexities, what is clear is that people who may be suicidal should not have access to firearms when they are most at risk. Suicidality is often a passing urge — many people who consumed large amounts of pills and survived later say they regret their suicidal action — and firearms offer little chance of survival.

What can we do?

To help address the risk of gun-related suicides, providers need the training, skills, and resources to systematically screen patients for depression and discuss firearm safety when clinically indicated. At the institutional level, hospitals and health care systems also should incorporate policies and guidelines to facilitate comprehensive screening for depression and educate patients about firearm safety. For example, electronic health records could prompt clinicians to screen patients and conduct firearm conversations.

Medical schools should universally teach future clinicians the skills necessary for discussing firearm safety. Indeed, subject matter experts have developed consensus guidelines for educating all medical professionals about firearm injury and prevention, and several institutions have robust firearm-related efforts. Part of such education must involve discussing firearms with patients in ways that are respectful of their values and sensitive to their cultural experiences. Ample guidance in this area is available, such as the use of terminology that is most likely to resonate with different types of patients.

Ample guidance in this area is available, such as the use of terminology that is most likely to resonate with different types of patients.

Clinicians should also learn about ways to temporarily limit access to firearms when patients present a risk of harm to themselves or others. Depending on the state, options for limiting access include Extreme Risk Protection Orders (ERPOs) — also known as red flag laws — in which family members and law enforcement personnel may request that a judge require a person to temporarily relinquish their firearms. In addition, several states allow individuals who are concerned that they may harm themselves in the future to enroll voluntarily in a background check database that would prevent them from purchasing a firearm without a waiting period.

In 19 states and the District of Columbia, clinicians can also contact law enforcement to request that a judge issue a restraining order to separate firearms temporarily from people at high risk of harming themselves or others. In four states, clinicians are authorized to petition a court directly for an ERPO consistent with HIPAA privacy rules and with some legal immunity. These orders are time-limited, carry no criminal penalties, and do not create a criminal record. They also offer due process protections, respect the Second Amendment, and are supported by the majority of Americans, including a majority of gun owners.

In four states, clinicians are authorized to petition a court directly for an ERPO consistent with HIPAA privacy rules and with some legal immunity. These orders are time-limited, carry no criminal penalties, and do not create a criminal record. They also offer due process protections, respect the Second Amendment, and are supported by the majority of Americans, including a majority of gun owners.

We will never solve the problem of gun violence in America by “fixing mental health.” That is a simplistic notion, one that focuses on a serious but different public health problem.

In reality, the causes of gun violence in the United States are numerous and complex — and so are the solutions. But if we pursue proven measures designed to prevent access to firearms among people most at risk for perpetrating violence at their riskiest times, we will be moving significantly in the right direction. If health care providers use their influence to advocate for evidence-based gun safety policies and practices; if we implement firearm safety conversations systematically in clinical care; and if we teach these skills to future providers, we will save many more lives than if we only work to heroically treat yet another catastrophic shooting victim.

John Rozel, MD, MSL, is the medical director of resolve Crisis Services of UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital in Pittsburgh, a psychiatrist at the University of Pittsburgh, and an associate professor of psychiatry and adjunct professor of law at the University of Pittsburgh. He divides his time between emergency psychiatry and violence prevention.

Jeffrey Swanson, PhD, is a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina, and a faculty affiliate of the Center for Firearms Law at Duke Law School. He is a sociologist who collaborates across disciplines to build evidence for policies, laws, and interventions to improve outcomes for people with mental illnesses and to prevent firearm-related violence and suicide.

"Killed so many people? He's crazy!" Are you sure?

- Rachel Nuwer

- BBC Future

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you understand what's going on.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Every time a person in the middle of civilian life kills a lot of other people - opening fire at a school or a department store, on the street or in an office - our first, almost instinctive reaction is: "He's just crazy! ". Correspondent BBC Future decided to look at the example of the United States, if there are grounds for such a reaction.

In Stephen King's horror novel The Shining, protagonist Jack Torrance embodies the popular notion of a deranged killer unable to tell reality from hallucinations.

As Jack descends deeper into his madness, he falls under the influence of ghosts living in an empty hotel where he has taken a job as caretaker for the winter. The ghosts eventually convince Jack that he must kill his wife and son.

Readers of this book (or viewers of the film of the same name) may conclude that Torrance has fallen victim to the forces of evil inhabiting the hotel.

Or to interpret his gradual descent into insanity in a completely different way: Jack was mentally ill - perhaps schizophrenic - and his actions are explained by acute psychopathic attacks.

- What will happen to our world if all weapons disappear?

- Attacks on schools: is the Internet to blame again?

- The right to bear arms - the right to defend or sow death?

- Are aggression and violence related to mental illness?

The Shining is, of course, fiction. But even in life, when it comes to mental illness and its association with violence, society, the media, and politicians often find it difficult to distinguish fact from fantasy.

Opinion polls consistently show that the majority of US adults believe that people with mental illness are more violent.

And this view is strengthened every time there is another shooting with many innocent victims, which leads to growing calls for reform of the mental health system.

But is there any evidence that mental illness and violence are linked?

Do those who shoot at schools and department stores, on the streets and in offices suffer from mental illness?

Image copyright DAVID GANNON/AFP/Getty Images

Image captionThe story of Jack Torrance, played by Jack Nicholson, is, of course, a fabrication. But the protagonist of this King novel is the epitome of the popular notion of a deranged killer who can't tell reality from hallucinations.0011

Skip Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

If social media and sensational media headlines are to be believed, the fear of unusually violent, violent acts by mentally ill people is fairly common.

"The idea of someone losing control of their thoughts and actions makes people fearful," says Paul Appelbaum, a psychiatrist at Columbia University College of Medicine.

"In addition, we all tend to remember unusual events better, so acts of violence committed by mentally ill people remain in our memory for a long time."

Terrible in its senselessness, massacres tend to kindle a thirst for a quick answer to the question of why this happened and how to avoid it in the future. And a simple and easy-to-understand answer is desirable, says Jeffrey Swanson, professor of psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine.

"We want our lives to be safe, predictable and meaningful," he says. "It's a normal human reaction to want a very simple and complete explanation quickly. So that we can put it in a box and write on it: "Crazy ".

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Grossly senseless mass murder fuels a thirst for a quick and simple answer to why it happened

However, this instinctive societal response creates a problem, he continues, as it reinforces ostracism, to which mentally ill citizens are subjected, already suffering enough from discrimination of all kinds. 0011

0011

Suffice it to say that such people are three times more likely than the average American to become victims of violence, they are much more vulnerable.

Yes, some acts of violence, including massacres, were indeed committed by mentally ill people. For example, law student Wendell Williamson, who shot and killed two strangers on Chapel Hill Street in North Carolina, was subsequently diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

Williamson claimed that he acted in the belief that he was saving the world, and the court eventually found him not guilty on the grounds that he was mentally ill.

But such cases are in the minority, Swanson points out. In fact, a very small number of mass murderers suffer from serious mental illnesses that can be diagnosed - say, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

A 2004 study of more than 60 North American mass murderers found that only 6% were psychotic at the time of the crime.

Mental illness is responsible for “less than 1% of gun homicides per year,” according to a study published in 2016.

And other scientific works show that in the US, people with mental disabilities are responsible for only 3-5% of cases of violence (much lower than the proportion of mentally ill citizens in the US population as a whole - about 18%).

As Applebaum points out, others still account for about 96% of violence.

Image copyright Taimy Alvarez-Pool/Getty Images

Image captionA school shooting in Parkland, Florida, has killed 17 people. 19-year-old Nicholas Cruz (pictured in court on April 27, 2018) was detained an hour later and fully admitted his guilt. He didn't look like a madman...

Moreover, those cases of violence involving people with serious mental illness are not the most severe violations. For example, this is verbal abuse or beatings, and not murder at all (there is, however, the problem of suicides), and they are directed, as a rule, against those with whom this person lives, and not at strangers, and they are not on a mass scale.

In addition, serious attacks require planning and organization, which is often beyond the reach of people with mental disabilities.

For example, a study published in 2014 found that only 2% of 951 hospital discharged patients committed an act of violence with a firearm, and only 6% of them did so to a stranger.

A 2011 meta-analysis of more than 700 cases of homicides committed by people with diagnosed mental illness found that only 3 to 14% of victims were strangers to the killer.

But even in cases where people with severe mental disabilities are responsible for the violence, it's very difficult to definitively attribute their illness to the cause of these crimes, Swanson notes.

Various co-variables - such as childhood abuse, alcohol or drug abuse - increase the likelihood that a person will resort to violence.

Image copyright Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Image caption Young Americans demonstrate to demand a ban on gun ownership. Do you want to offer them instead to strengthen the mental health care system?

Do you want to offer them instead to strengthen the mental health care system?

"Take away the additional risk factors and take mental illness as such - it has little to do with violence," says Swanson.

In the light of another tragedy, however, many will find it extremely difficult to accept these conclusions of scientists.

"For example, when there's another school shooting, people say whoever did such a terrible thing must be crazy," says Renee Binder, a professor at the University of California and director of the Psychiatry and Law Program at San Francisco Medical School. .

"But we have to be very careful with such definitions, because although there is definitely something wrong with such people, often it is not a mental illness at all."

Also in the US, by linking murders and mental disorders without proper reason, we are shifting the focus of the debate from discussing the possibility of a ban on possession of firearms to improving the mental health system, which, of course, plays into the hands of the powerful gun lobby in this country.

It is rather difficult to accurately determine the degree of mental health of those who carry out massacres of civilians, since they often commit suicide immediately after the crime - or they are found by a police bullet.

But what scientists and doctors know for sure is that these criminals are often angry young people who feel they are being treated unfairly by society and are out for revenge.

The problem, however, is that under such a definition - "embittered young people" - tens of thousands fall, but the vast majority of them do not kill because of this.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Most US adults believe that people with mental illness are more violent

"If we could do something about the male population, we would certainly be able to reduce the number of cases of violence and crime in general," says Swanson. "But you can't neutralize all men."

It is almost impossible to predict and calculate who exactly will commit mass murder, he says.

Some of these killers even visited a psychotherapist on the eve of the crime, but no specific diagnosis related to mental illness was made.

"Most of those who commit such crimes do not want to be treated and do not qualify for treatment," says Binder.

In the same way, you cannot be placed in a psychiatric hospital just because you are angry at the whole world.

All this means that strengthening the treatment of mentally ill citizens (which in itself, of course, is a good thing) will not solve the problem of gun violence in the United States, Swanson insists.

If we consider cases of shooting on the streets of peaceful cities as the work of mentally abnormal citizens, this will in no way help to avoid new tragedies, but will only add fears of people suffering from mental disorders - and these fears are based not on facts, but on fiction.

Read the original English version of this article at BBC Future .

US gun control

Following the massacre of 49 people by one shooter at a gay nightclub in Florida, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein called for the leaders of the United States of America to fulfill their obligations to protect their citizens from "The appallingly common yet preventable violent attacks that are the direct result of inadequate gun control."

"It is difficult to find a rational explanation for the ease with which people can buy firearms, including assault rifles, despite having a history of crime, drug use, domestic violence and mental illness, or they directly contact extremists both at home and abroad," High Commissioner Zeid said.

“How many more massacres of schoolchildren, colleagues, African-American parishioners, how many more assassination attempts on talented musicians like Christina Grimmie or politicians like Gabriel Giffords will be needed before the US imposes heavy regulation of the sale and use of weapons? Why should any citizen be able to acquire assault weapons anywhere, or other powerful weapons designed to kill large numbers of people?" - added the head of the UN for human rights.

"Irresponsible propaganda for the acquisition of guns claims that firearms make society safer, when everything says otherwise," Zeid said. “With the availability of weapons, the urge to kill can easily turn into a lethal act. The path from hate speech to violent hate crime has accelerated. Society, in particular the most vulnerable communities and minorities, who already face widespread prejudice, pays a heavy price. price for not being able to stand up to lobbyists and take the necessary steps to protect people from gun violence.”

New UN human rights report on the acquisition, possession and use of firearms by civilians highlights the 'devastating impact' of gun violence on a range of human rights, including the right to life, security, education, health care, an adequate standard of living and participation in cultural life . The report states that women and children are often victims of gun-related violence, including through the use of guns to commit rape and other sexual violence, kidnapping, assault and domestic violence.

It states that the protection of human rights should be central to the development of laws and regulations relating to the availability, transfer and use of firearms. UN and regional human rights experts have long recommended that gun control measures include, among other things, a thorough background check system, periodic license checks, a clear gun confiscation policy in the context of domestic violence cases, mandatory training, and the criminalization of the illegal sale of firearms.

"Examples from around the world clearly demonstrate that the legal framework to control the acquisition and use of firearms has resulted in a dramatic reduction in violent crime," said the High Commissioner. "In the US, however, there are hundreds of millions of weapons in circulation and thousands of people are killed or injured each year."

Zeid added that "in particular, it is reprehensible (and actually dangerous) that this horrific event is already being used to encourage homophobic and Islamophobic sentiment.