How to write a diagnosis for dsm 5

DSM-5: Diagnosing and Report Writing | DSM-5® and the Law: Changes and Challenges

Navbar Search Filter Oxford AcademicDSM-5® and the Law: Changes and ChallengesForensic PsychiatryPsychiatryBooksJournals Mobile Enter search term

Close

Navbar Search Filter Oxford AcademicDSM-5® and the Law: Changes and ChallengesForensic PsychiatryPsychiatryBooksJournals Enter search term

Advanced Search

-

Cite Icon Cite

-

Permissions

-

Share

- More

Cite

Scott, Charles (ed. ), 'DSM-5: Diagnosing and Report Writing', in Charles Scott (ed.), DSM-5® and the Law: Changes and Challenges (

, 2015; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Aug. 2015), https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199368464.003.0003, accessed 10 Mar. 2023.

Select Format Select format.ris (Mendeley, Papers, Zotero).enw (EndNote).bibtex (BibTex).txt (Medlars, RefWorks)

Close

Navbar Search Filter Oxford AcademicDSM-5® and the Law: Changes and ChallengesForensic PsychiatryPsychiatryBooksJournals Mobile Enter search term

Close

Navbar Search Filter Oxford AcademicDSM-5® and the Law: Changes and ChallengesForensic PsychiatryPsychiatryBooksJournals Enter search term

Advanced Search

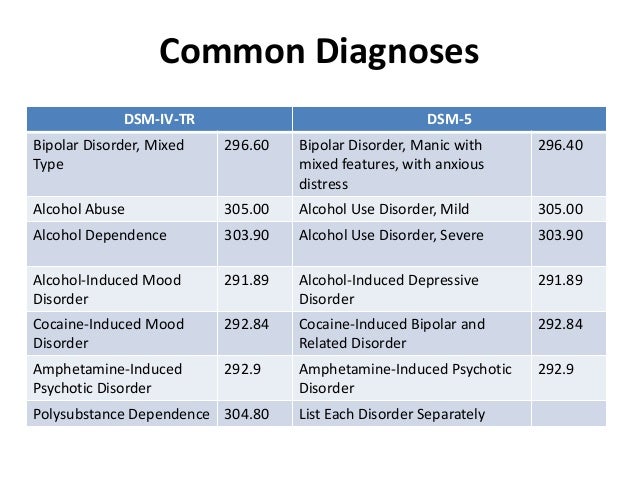

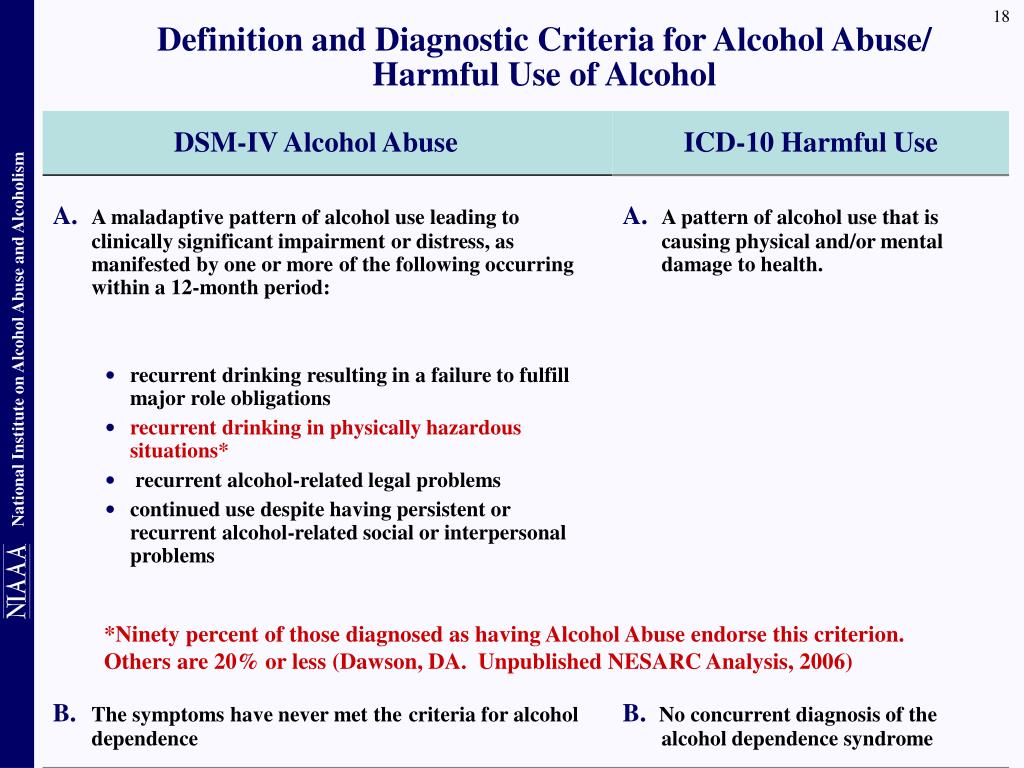

Abstract

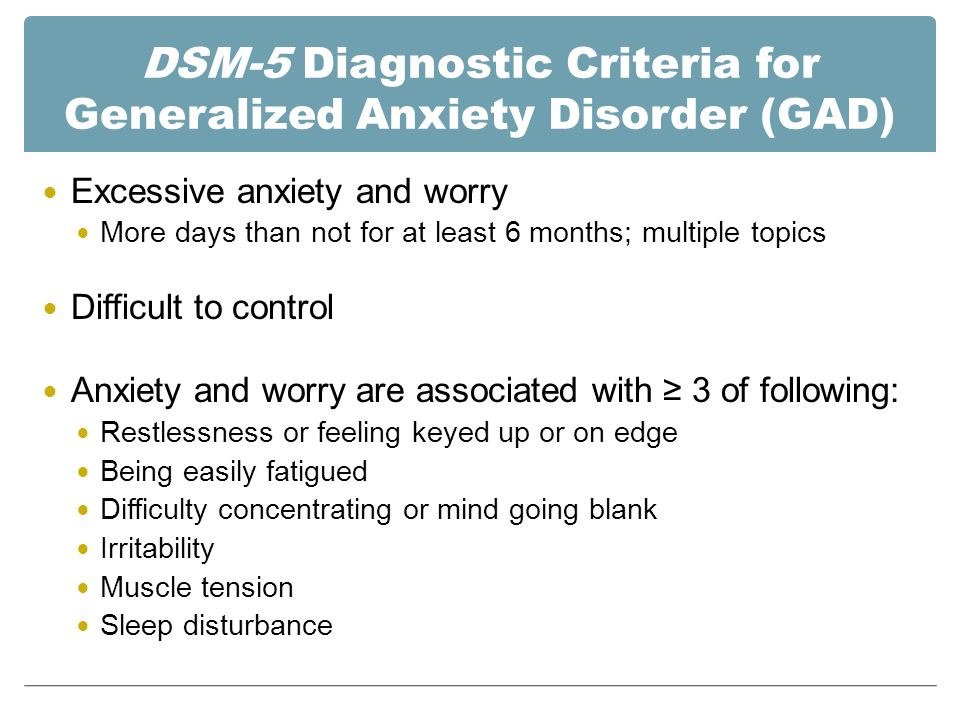

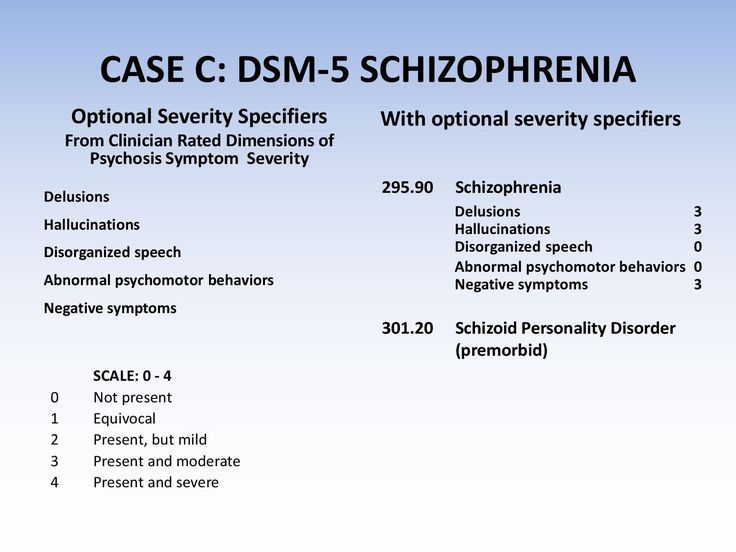

DSM-5 profoundly changes how diagnoses are listed and described. This chapter provides eight practical steps to assist clinicians and forensic evaluators in accurately recording and describing DSM-5 diagnoses in clinical records and forensic reports. These eight important steps include the following: understanding the difference between a “diagnosis” and “disorder”; evaluating criteria relevant to making a diagnosis; evaluating applicability of subtypes and specifiers; applying the correct International Classification of Disorders Code (ICD) if required; evaluating which diagnoses are “current”; explaining diagnoses in a forensic report; and determining if and how “disability” is assessed under DSM-5. In addition, this chapter reviews the use of severity rating instruments with a particular focus on quantitative assessments of psychotic symptom severity.

This chapter provides eight practical steps to assist clinicians and forensic evaluators in accurately recording and describing DSM-5 diagnoses in clinical records and forensic reports. These eight important steps include the following: understanding the difference between a “diagnosis” and “disorder”; evaluating criteria relevant to making a diagnosis; evaluating applicability of subtypes and specifiers; applying the correct International Classification of Disorders Code (ICD) if required; evaluating which diagnoses are “current”; explaining diagnoses in a forensic report; and determining if and how “disability” is assessed under DSM-5. In addition, this chapter reviews the use of severity rating instruments with a particular focus on quantitative assessments of psychotic symptom severity.

Keywords: DSM-5, ICD, disability, severity rating, report writing, forensic, legal, specifier DSM-5, ICD, disability, severity rating, report writing, forensic, legal, specifier

Subject

PsychiatryForensic Psychiatry

Disclaimer

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always …

More

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct.

Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up to date published product information and data sheets

provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and the publishers do not accept responsibility or

legal liability for any errors in the text or for the misuse or misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages

and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breastfeeding.

Readers must therefore always …

More

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct.

Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up to date published product information and data sheets

provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and the publishers do not accept responsibility or

legal liability for any errors in the text or for the misuse or misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages

and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breastfeeding.

You do not currently have access to this chapter.

Sign in

Get help with access

Get help with access

Institutional access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth / Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

Personal account

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

Institutional account management

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Purchase

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

Purchasing information

DSM-5® and the Law: Changes and Challenges

-

Cite Icon Cite

-

Permissions

-

Share

- More

Cite

Scott, Charles (ed. ), DSM-5® and the Law: Changes and Challenges (

), DSM-5® and the Law: Changes and Challenges (

, 2015; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Aug. 2015), https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199368464.001.0001, accessed 9 Mar. 2023.

Select Format Select format.ris (Mendeley, Papers, Zotero).enw (EndNote).bibtex (BibTex).txt (Medlars, RefWorks)

Close

Navbar Search Filter Oxford AcademicDSM-5® and the Law: Changes and ChallengesForensic PsychiatryPsychiatryBooksJournals Mobile Enter search term

Close

Navbar Search Filter Oxford AcademicDSM-5® and the Law: Changes and ChallengesForensic PsychiatryPsychiatryBooksJournals Enter search term

Advanced Search

Abstract

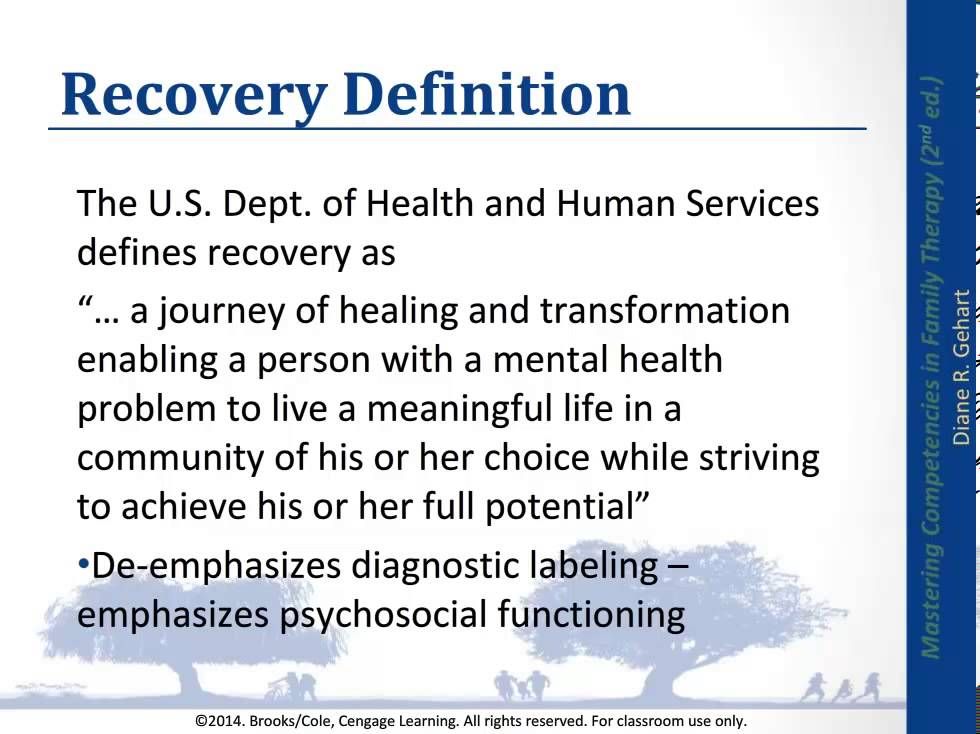

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) is the most widely used and accepted scheme for diagnosing mental disorders in the United States and beyond. DSM-5 was released with profound changes revealed in the required diagnostic process, specific criteria for previously established diagnoses, as well as the addition and deletion of specific mental disorders. This resource provides an excellent summary of the DSM-5 diagnostic changes and the implications of these changes in various types of criminal and civil litigation. It also provides practical guidelines on how to correctly use the DSM-5 diagnostic process to record diagnoses in a forensic report. Furthermore, this title highlights unique aspects of the assessment of malingering based on DSM-5 alterations of DSM-IV.

DSM-5 was released with profound changes revealed in the required diagnostic process, specific criteria for previously established diagnoses, as well as the addition and deletion of specific mental disorders. This resource provides an excellent summary of the DSM-5 diagnostic changes and the implications of these changes in various types of criminal and civil litigation. It also provides practical guidelines on how to correctly use the DSM-5 diagnostic process to record diagnoses in a forensic report. Furthermore, this title highlights unique aspects of the assessment of malingering based on DSM-5 alterations of DSM-IV.

Keywords: civil, criminal, diagnosis, disability, DSM-5, evaluation, forensic, law, litigation, malingering, mental disorder, mental health

Subject

PsychiatryForensic Psychiatry

Disclaimer

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always …

More

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct.

Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up to date published product information and data sheets

provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and the publishers do not accept responsibility or

legal liability for any errors in the text or for the misuse or misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages

and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breastfeeding.

Readers must therefore always …

More

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct.

Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up to date published product information and data sheets

provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and the publishers do not accept responsibility or

legal liability for any errors in the text or for the misuse or misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages

and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breastfeeding.

Contents

-

Front Matter

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

-

Expand

1

DSM-5: Development and Implementation

-

Expand

2

The DSM-5 and Major Diagnostic Changes

-

Expand

3

DSM-5: Diagnosing and Report Writing

-

Expand

4

DSM-5 and Psychiatric Evaluations of Individuals in the Criminal Justice System

-

Expand

5

DSM-5: Competencies and the Criminal Justice System

-

Expand

6

DSM-5 and Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity and Diminished Mens Rea Defenses

-

Expand

7

DSM-5 and Civil Competencies

-

Expand

8

DSM-5 and Personal Injury Litigation

-

Expand

9

DSM-5 and Disability Evaluations

-

Expand

10

DSM-5 and Education Evaluations in School-Aged Children

-

Expand

11

DSM-5 and Malingering

-

End Matter

- Index

Sign in

Get help with access

Get help with access

Institutional access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth / Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

Personal account

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

Institutional account management

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Purchase

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

Purchasing information

Advertisement

Advertisement

New American classification of mental disorders DSM-5 released to the world

Home > News > The new American classification of mental disorders DSM-5 is released to the world

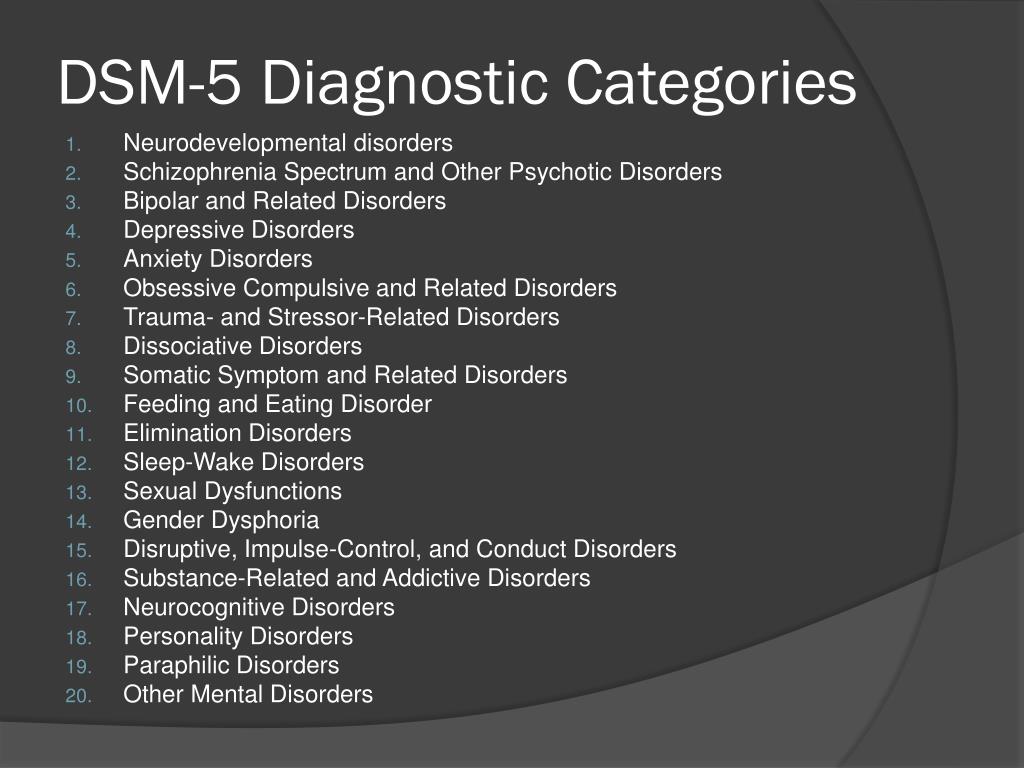

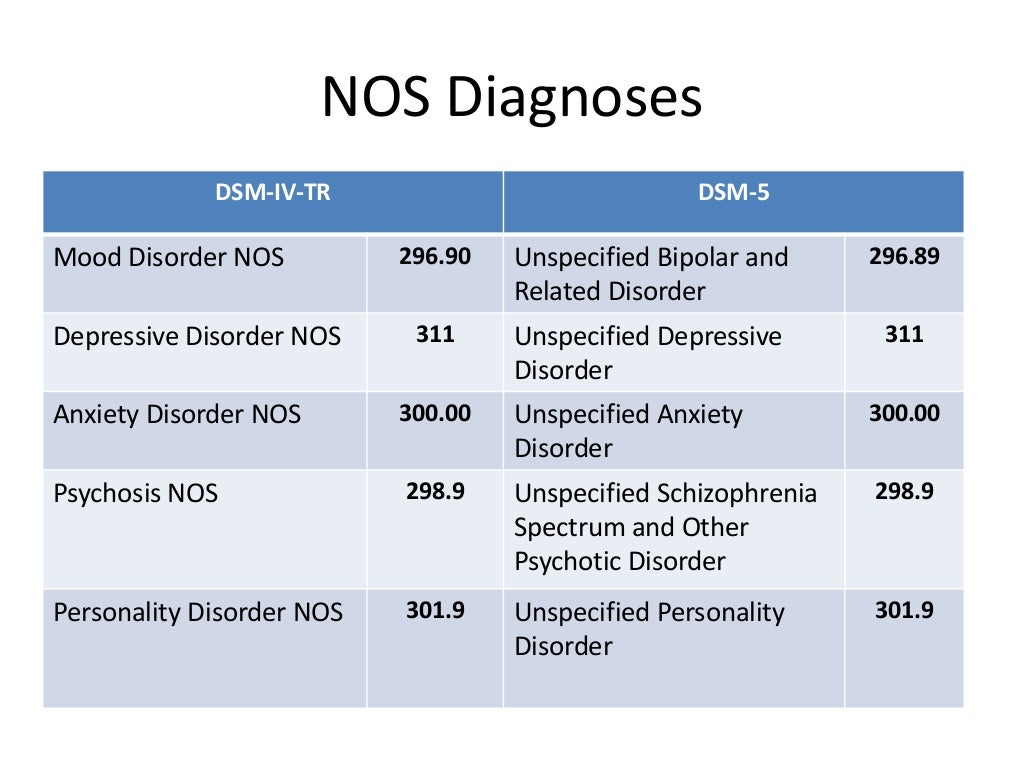

| DSM-5 consists of three sections: it is (1) an introductory part with instructions for use and a warning about the forensic psychiatric use of the DSM-5; (2) diagnostic criteria and codes for routine clinical use; and (3) tools and techniques to inform clinical decision making. Major changes:

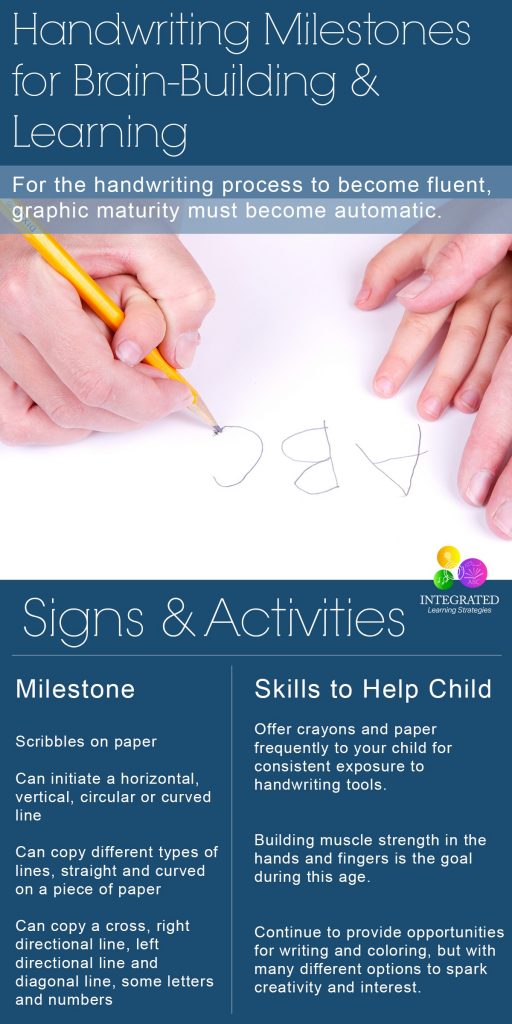

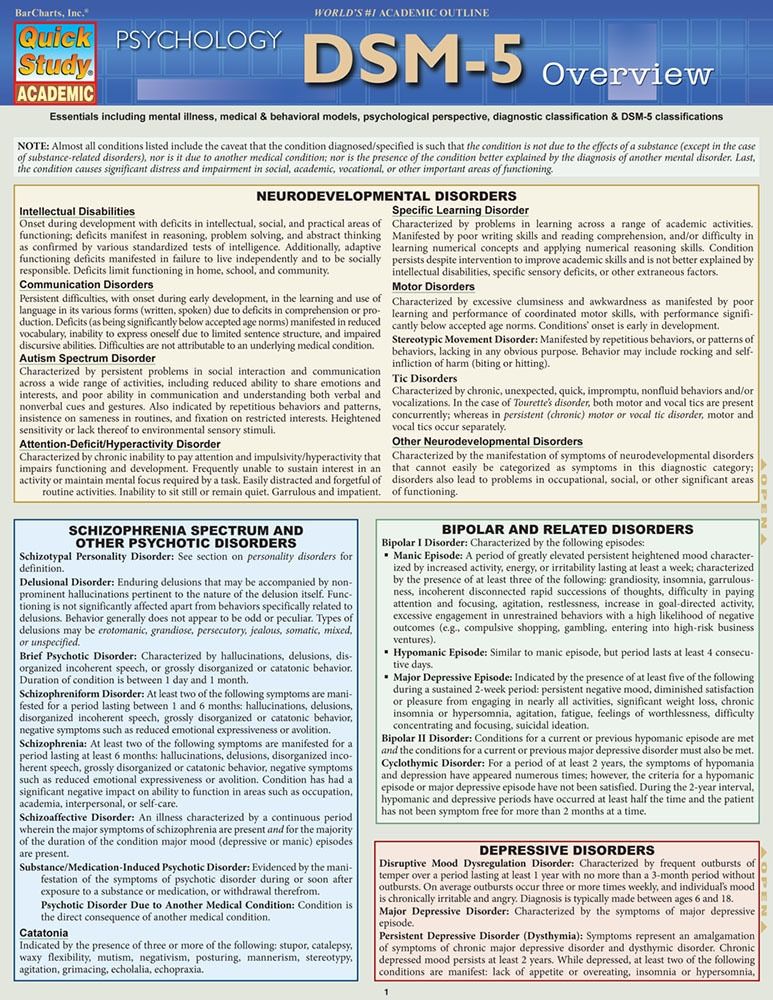

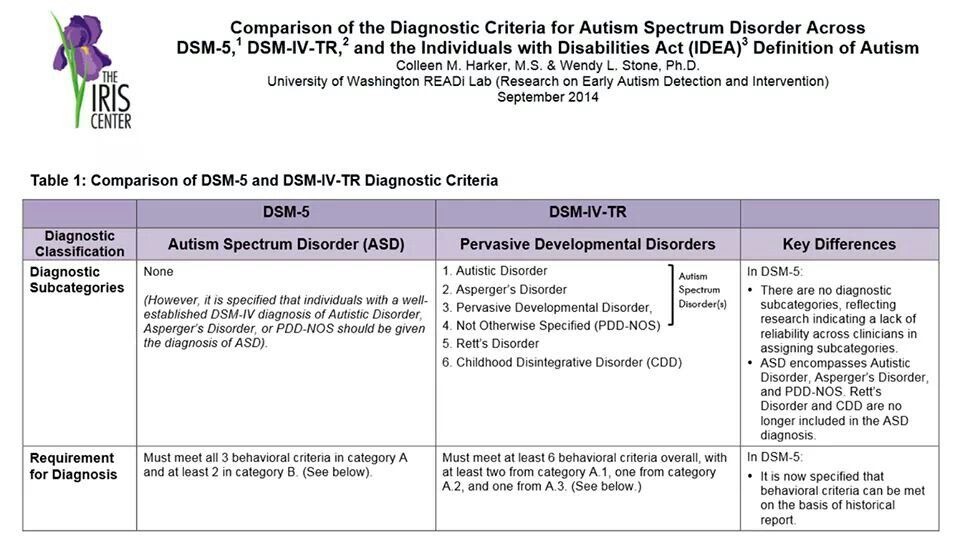

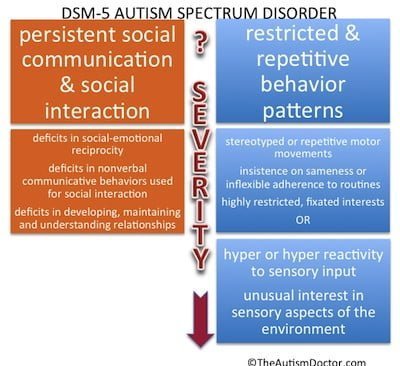

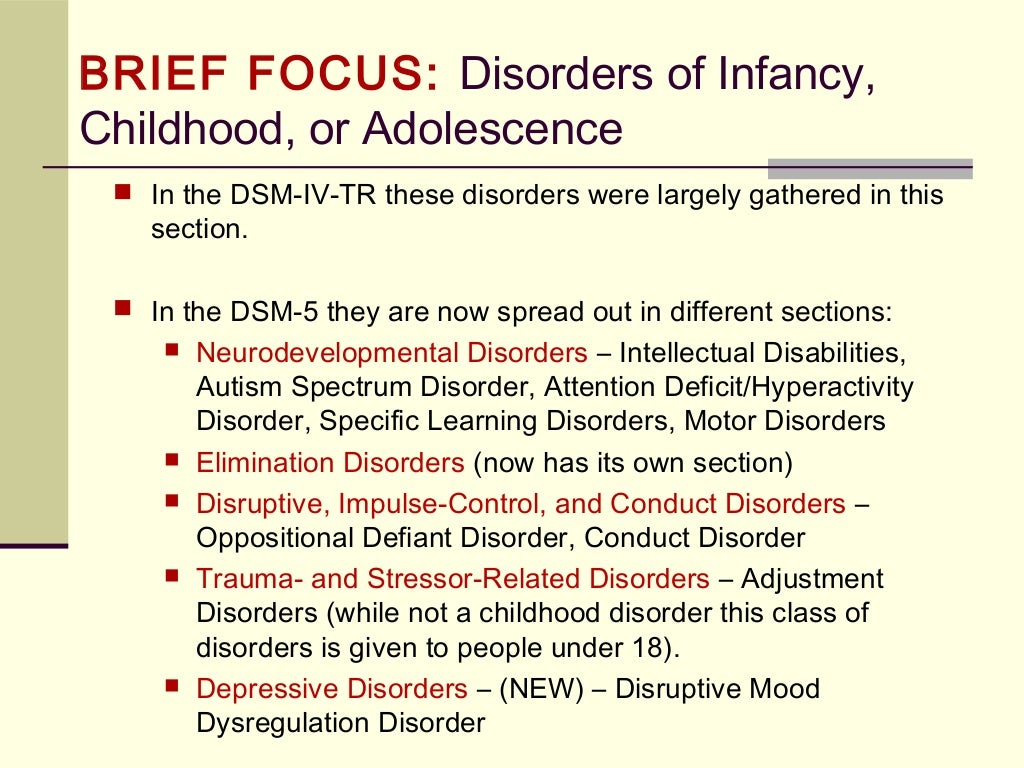

The severity of the disorder is not determined by IQ, but by the level of adaptive functioning. Speech disorders have entered the new category "social communication disorder", in which some of the syndromes coincide with "autism spectrum disorder". The category "Autism Spectrum Disorders" replaces the DSM-4 diagnoses of autism, Asperger's syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and an unspecified general developmental disorder, all of which cease to exist as separate diagnoses. ADHD can start later (before 12) and is treated differently in different areas. Learning disorders and movement disorders are organized differently in this chapter and somewhat combined.

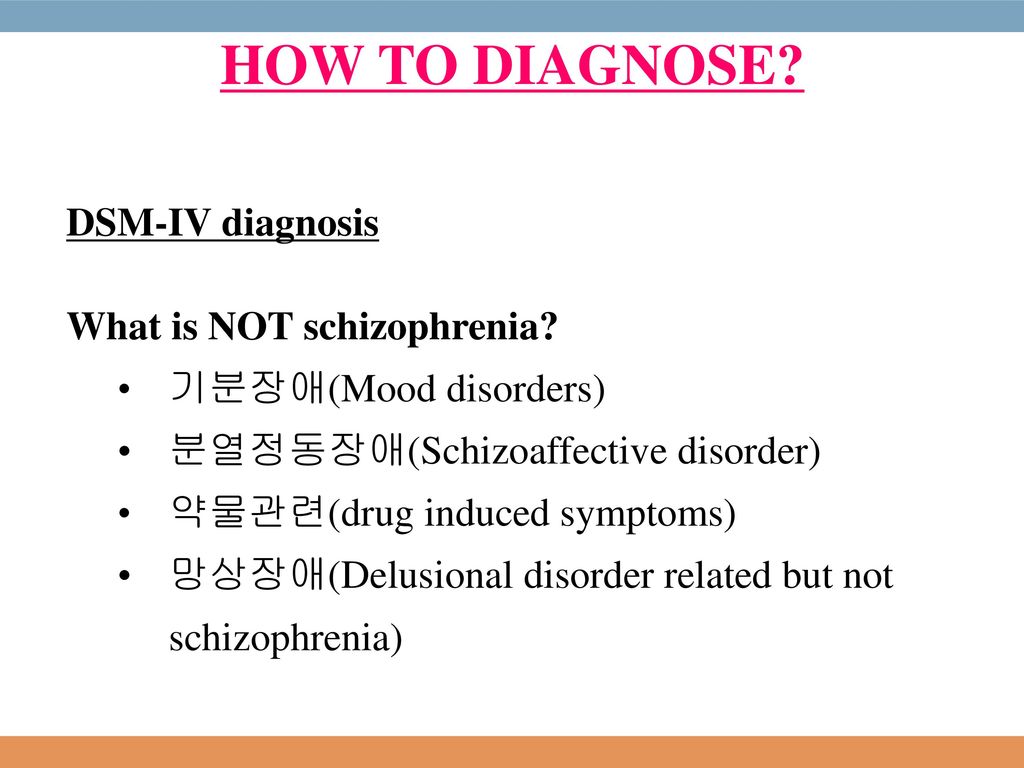

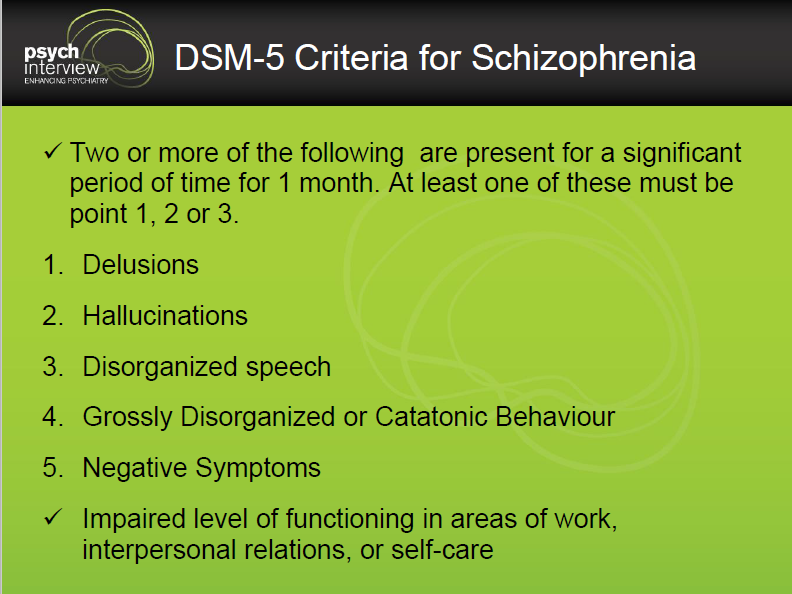

For the diagnosis of schizophrenia, symptoms of the first Schneider rank lose their special weight. One positive symptom is required for a diagnosis to be made.

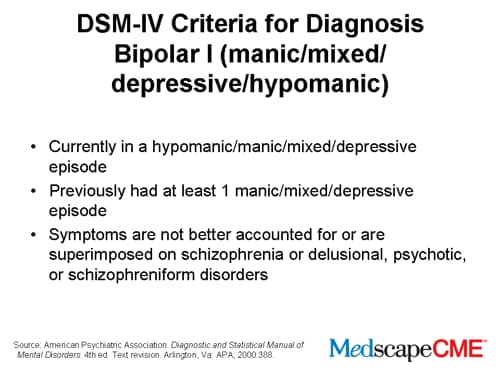

Bipolar and related disorders are now separated from depressive disorders and placed in a separate category. A clearer definition of mania is given and refinements for mixed episodes are introduced, which lowers the threshold for disorder. Added a residual subcategory ""other"" and a qualifying score for anxiety symptoms.

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and premenstrual dysphoric disorder added. Chronic depression and dysthymia are combined into one diagnosis, now it is ""persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia)"" with a number of clarifying indicators.

|

ISSN 2588-0519 (Print)

ISSN 2618-8473 (Online)

Autism spectrum disorder in DSM-5 code 299.00

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition) is a nosological system used in the United States since 2013, a “nomenclature” of mental disorders. Developed and published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). DSM-5 published May 18, 2013, supersedes DSM-IV-TR 2000.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a spectrum of psychological characteristics describing a wide range of abnormal behaviors and difficulties in social interaction and communication, as well as severely limited interests and frequently repetitive behaviors.

Entered "Autism Spectrum Disorder":

- autism (Kanner syndrome)

- Asperger's syndrome

- childhood disintegrative disorder

- non-specific pervasive developmental disorder

DSM-5 includes for autism spectrum disorders (Autism Spectrum Disorder, ASD) 299.00 (F84.0) the following diagnostic criteria:

A. context, manifested at the moment or in history in the following (examples are given for clarity and are not exhaustive, see text):

1. Deficiencies in social-emotional reciprocity; starting, for example, with abnormal social convergence and failures to maintain normal dialogue; to reduce the exchange of interests, emotions, as well as the impact and response; to the inability to initiate or respond to social interactions.

2. Deficiencies in nonverbal communicative behavior used in social interaction; starting, for example, with poor integration of verbal and non-verbal communication; to anomalies in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and using non-verbal communication; to the complete absence of facial expressions or gestures.

3. Deficits in establishing, maintaining and understanding social relationships; starting, for example, with difficulties in adjusting behavior to different social contexts; to difficulty participating in imaginative games and making friends; to a visible lack of interest in peers.

B. Limited, repetitive pattern of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following (examples are provided for illustrative purposes and are not meant to be exhaustive; see text):

1. Stereotypical or repetitive motor movements, speech, or use of objects (eg, simple motor stereotypes, lining up toys or waving objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

2. Excessive need for consistency, inflexible adherence to rules or patterns, ritualized forms of verbal or non-verbal behavior (eg, extreme stress at the slightest change, difficulty shifting attention, inflexible thought patterns, congratulatory rituals, insisting on a fixed route or meal ).

3. Extremely limited and fixed interests that are abnormal in intensity or direction (for example, strong attachment to or excessive preoccupation with and infatuation with unusual objects, extremely limited scope of activities and interests, or perseveration).

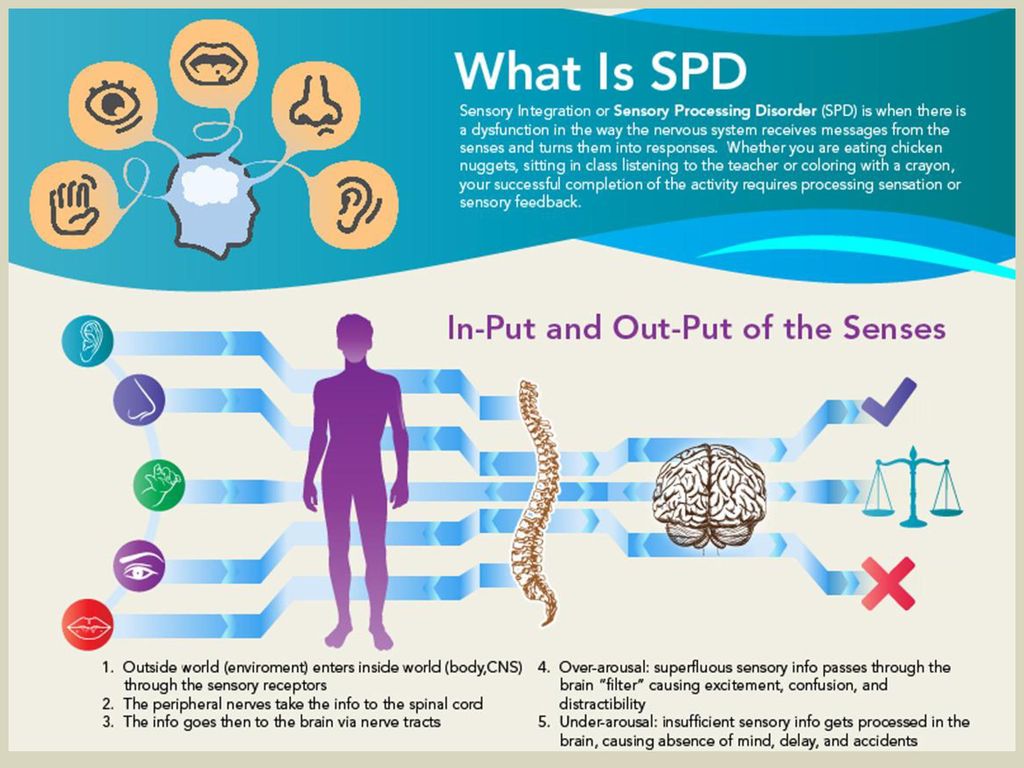

4. Over- or under-reacting to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (eg, apparent indifference to pain or ambient temperature, negative response to certain sounds or textures, excessive sniffing or touching of objects, fascination with light sources or objects in motion).

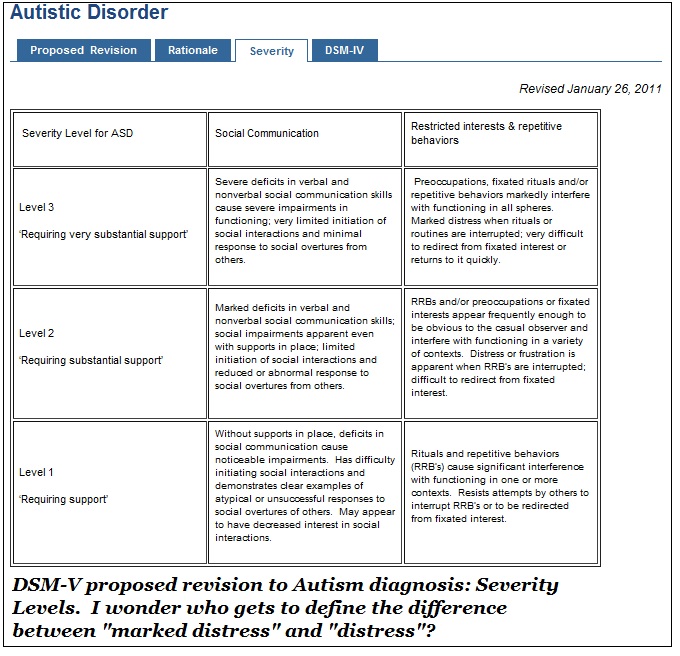

Specify severity:

Severity is based on impaired social interaction and limited, repetitive behaviors (see Table 2).

p. Symptoms must be present early in development (but may not become fully apparent until social demands exceed limited capacity, or be masked by learned strategies later in life).

D. Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of daily functioning.

E. These disorders are not due to intellectual disability (mental retardation) or general developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders often coexist; in order to diagnose comorbidity between autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation, social communication must be below what is expected for the general level of development.

Note:

Individuals with well-established DSM-IV autism, Asperger's syndrome, or non-specific pervasive developmental disorder (PDD-NOS) under the DSM-V will be diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Individuals with significant social communication and interaction impairments whose symptoms do not meet criteria for autism spectrum disorder should undergo a diagnostic evaluation for social communication (pragmatic) disorder (315.39(F80.89)).

Additionally specify:

With/Without accompanying mental retardation (developmental delay).

With/Without an accompanying defect (speech disorder).

A disorder associated with a medical condition, or genetics, or a known environmental factor. (Coded note: Use additional code(s) to identify associated medical or genetic conditions.)

A disorder associated with impaired development, behavior, mental or other abilities of a neurological nature. (Coded note: Use additional code(s) to define neurodevelopmental mental or behavioral disorders.)

With/Without catatonia(s) (see criteria for catatonia associated with another psychiatric disorder, pp. 119-120, for a definition). (Coded note: Use additional code 293.89 [F06.1] for autism-related catatonia to indicate the presence of comorbid catatonia.) Severity

For example, a person with a small set of a few understandable words, occasionally initiating social interaction, and if he initiates, he turns in an unusual form and only to satisfy needs, and responds only to very direct instructions and forms of social communication.

For example, a person with a small set of a few understandable words, occasionally initiating social interaction, and if he initiates, he turns in an unusual form and only to satisfy needs, and responds only to very direct instructions and forms of social communication.

Subtypes are removed - in favor of the dimensional indicator of severity. For schizoaffective disorder, the mood aspect is emphasized, and for delusional disorder, frivolous content is no longer excluded – although it is evaluated separately. The "catatonia" section has been expanded: this code can now be entered as an adjacent diagnosis (specifying indicator) for depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders.

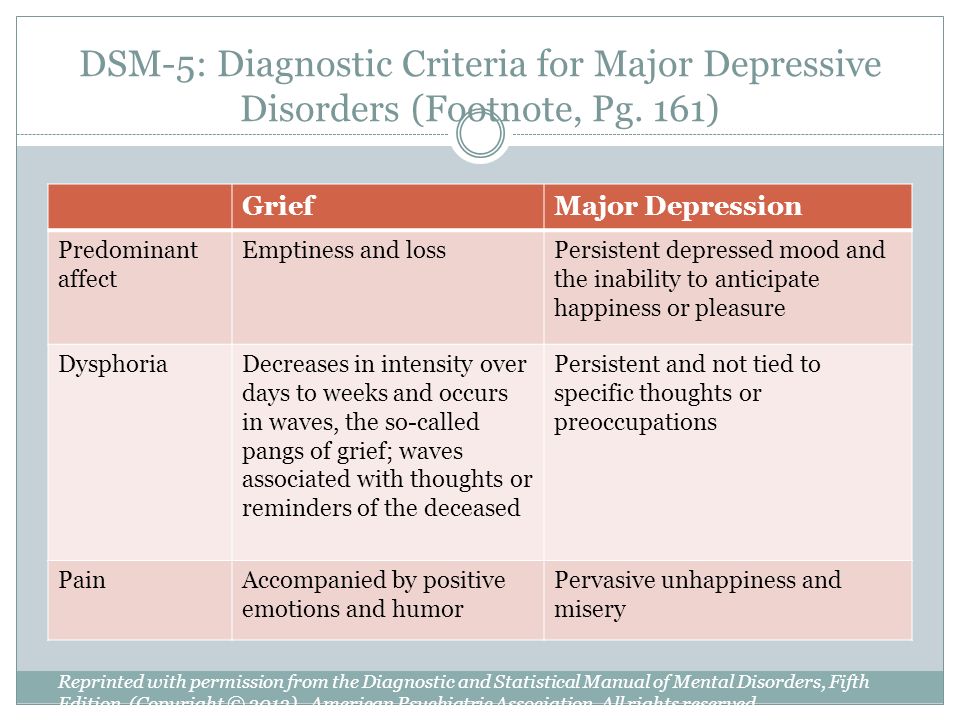

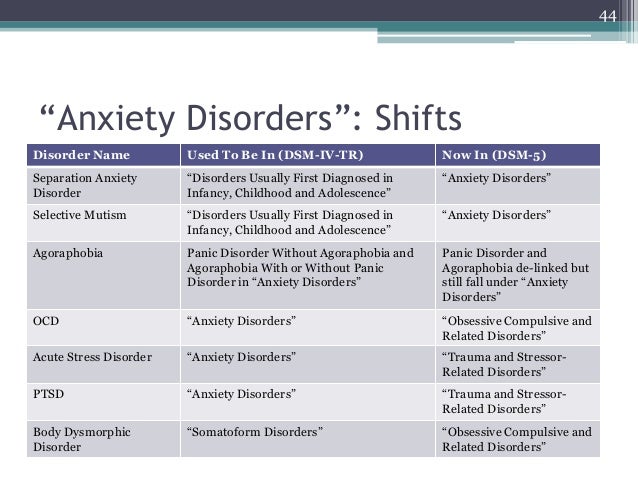

Subtypes are removed - in favor of the dimensional indicator of severity. For schizoaffective disorder, the mood aspect is emphasized, and for delusional disorder, frivolous content is no longer excluded – although it is evaluated separately. The "catatonia" section has been expanded: this code can now be entered as an adjacent diagnosis (specifying indicator) for depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders.  Major depressive disorder remained virtually unchanged, however, for "subthreshold" symptoms, a clarifying indicator ""mixed manifestations"" was introduced. A clarifying indicator for anxious distress has also been introduced. Removed grounds for exclusion for grief. 9(see below) Various phobia criteria are slightly adapted, and agoraphobia and panic are decoupled. Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses.

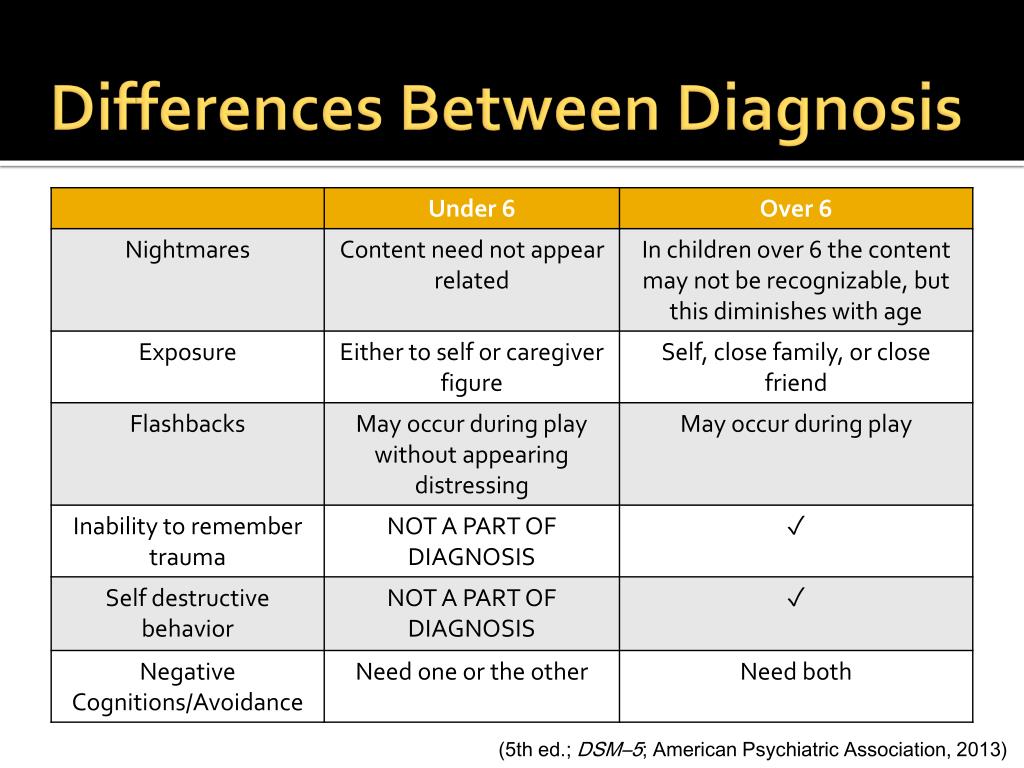

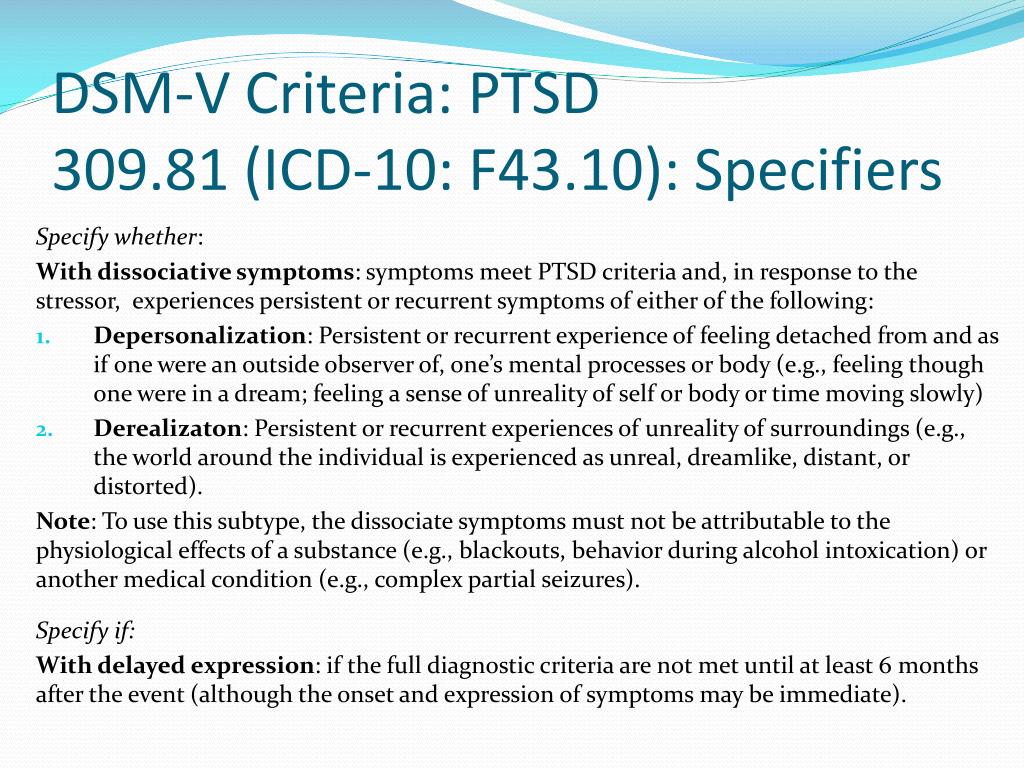

Major depressive disorder remained virtually unchanged, however, for "subthreshold" symptoms, a clarifying indicator ""mixed manifestations"" was introduced. A clarifying indicator for anxious distress has also been introduced. Removed grounds for exclusion for grief. 9(see below) Various phobia criteria are slightly adapted, and agoraphobia and panic are decoupled. Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses.  Also ruled out is the requirement to directly experience fear, horror, or feelings of helplessness. Avoidance and emotional flattening are separated, and at the same time, emotional flattening is added, incl. persistent depressed mood. Recklessness, (auto) destructive behavior, irritability and aggression are added to the already known symptoms of arousal. For children and adolescents in puberty, lower diagnostic thresholds are used. The adjustment disorder remained unchanged. Reactive attachment disorder has been moved to this chapter.

Also ruled out is the requirement to directly experience fear, horror, or feelings of helplessness. Avoidance and emotional flattening are separated, and at the same time, emotional flattening is added, incl. persistent depressed mood. Recklessness, (auto) destructive behavior, irritability and aggression are added to the already known symptoms of arousal. For children and adolescents in puberty, lower diagnostic thresholds are used. The adjustment disorder remained unchanged. Reactive attachment disorder has been moved to this chapter.  Removed somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, pain disorder, and unspecified somatoform disorder from DSM. A diagnosis of a "disorder with somatic symptoms" can be made on par with a diagnosis from another medical specialty only if the somatic symptoms are associated with abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Unexplained medical symptoms play a decisive role only in false pregnancy and conversion (i.e. functional disorder with neurological symptoms). In other cases, positive symptoms should be sought in this group.

Removed somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, pain disorder, and unspecified somatoform disorder from DSM. A diagnosis of a "disorder with somatic symptoms" can be made on par with a diagnosis from another medical specialty only if the somatic symptoms are associated with abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Unexplained medical symptoms play a decisive role only in false pregnancy and conversion (i.e. functional disorder with neurological symptoms). In other cases, positive symptoms should be sought in this group.  The chapter presents a large number of sleep disorders described in terms of physical characteristics in relation to circadian rhythms and respiratory disorders. This group includes Restless legs syndrome and REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. A large diagnostic choice predisposes to move away from the use of "unspecified" diagnoses.

The chapter presents a large number of sleep disorders described in terms of physical characteristics in relation to circadian rhythms and respiratory disorders. This group includes Restless legs syndrome and REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. A large diagnostic choice predisposes to move away from the use of "unspecified" diagnoses.  In addition to a variety of impulse control disorders, antisocial personality disorder, dubbed from the chapter on personality disorders, also got here. The criteria for oppositional defiant disorder have been revised and weighted. In conduct disorder (Conduct Disorder), the grounds for excluding the diagnosis have been removed, but the clarifying indicator “callous-unemotional” has been added. Intermittent Explosive Disorder can now be verbal, and the rest of the criteria for this disorder are much more refined.

In addition to a variety of impulse control disorders, antisocial personality disorder, dubbed from the chapter on personality disorders, also got here. The criteria for oppositional defiant disorder have been revised and weighted. In conduct disorder (Conduct Disorder), the grounds for excluding the diagnosis have been removed, but the clarifying indicator “callous-unemotional” has been added. Intermittent Explosive Disorder can now be verbal, and the rest of the criteria for this disorder are much more refined.