How to deal with intermittent explosive disorder

Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED) | Thriveworks

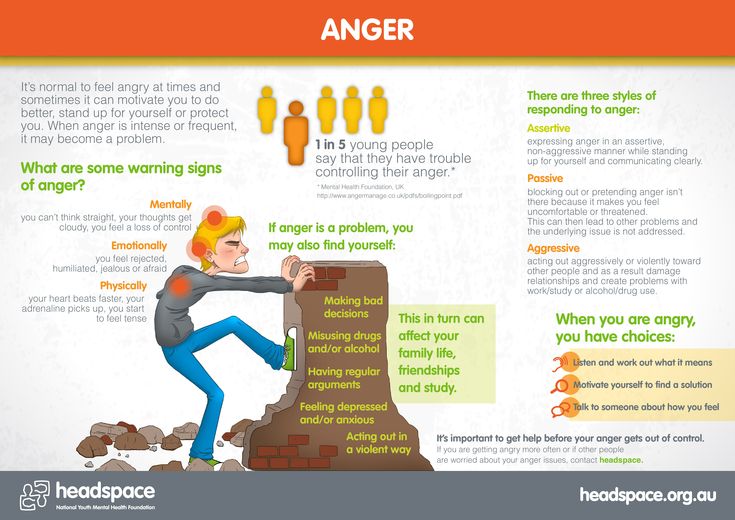

It’s uncomfortable (and even scary) to witness that one friend fly off the handle from a minor provocation or a stranger epically lose their cool in the grocery store. Big, aggressive behavior from our fellow humans can feel terrorizing, especially when they suggest physical violence. How can innocent bystanders wrap their heads around these kinds of angry outbursts?

If these explosions come out of nowhere and dissipate quickly, and they leave a number of scary consequences in their wake (like destroyed property or personal injury), there might be a psychiatric condition like intermittent explosive disorder underlying the outbursts.

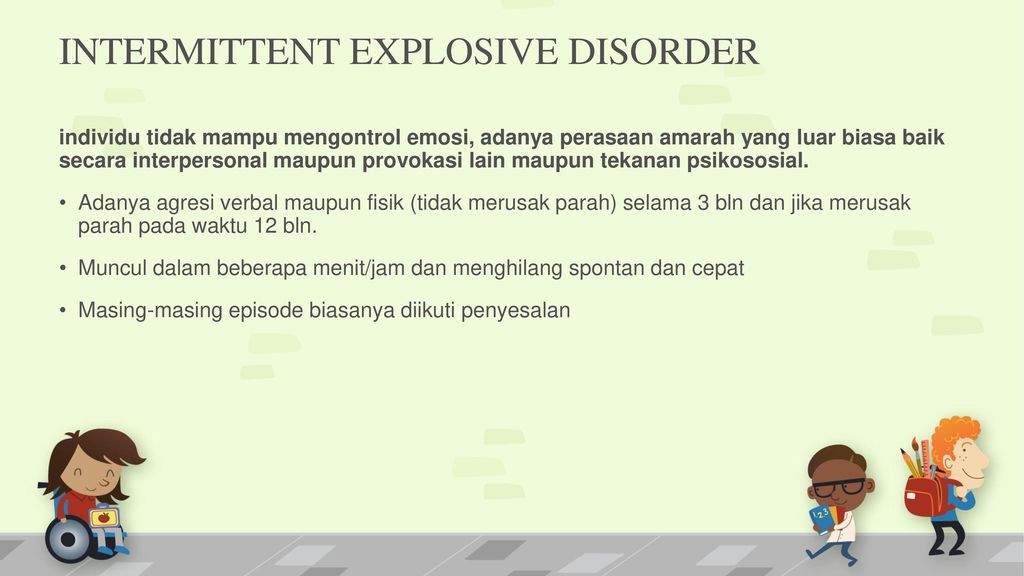

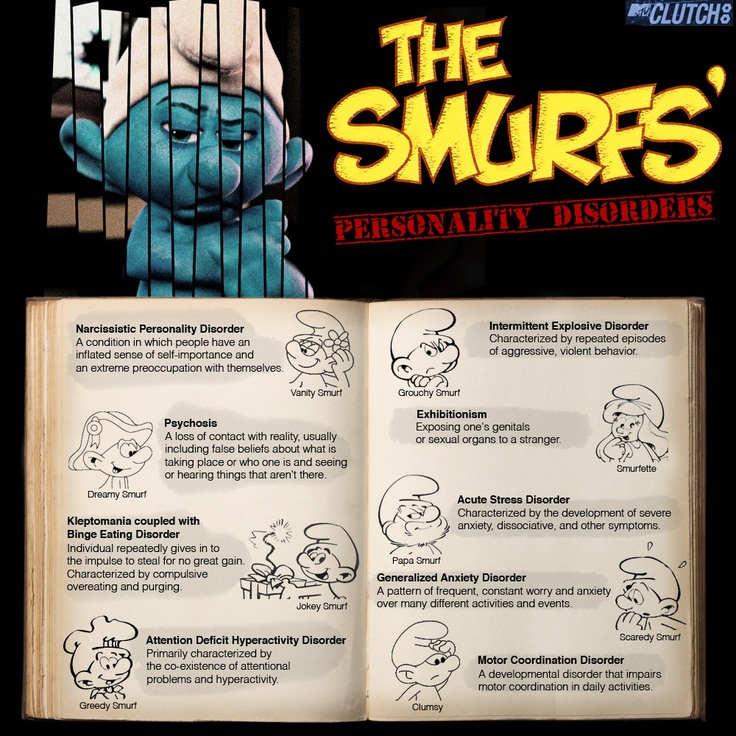

What Is Intermittent Explosive Disorder?Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is a mental health condition characterized by recurrent behavioral outbursts with high rates of anger and serious impulsive aggression toward others. People with intermittent explosive disorder cannot control their aggressive outbursts, which usually come on suddenly and target someone close to them.

To witnesses, these outbursts might seem like irrational “freakouts.” They can involve physical aggression, threats of violence, or verbal aggression. They usually last about 30 minutes and are typically followed by remorse, embarrassment, and distress.

Intermittent explosive disorder afflicts about 16 million people in the United States. It usually has an early onset, at a mean age of 12.

Is Intermittent Explosive Disorder a Serious Mental Illness?The disorder can lead to grave outcomes for relationships and employment. But fortunately, it is highly treatable. And while someone with the condition is getting treatment, there are ways that the people closest to them can help de-escalate IED episodes (more on this later).

What Type of Disorder Is Intermittent Explosive Disorder?Intermittent explosive disorder is a distinct, taxonic behavioral disorder as opposed to a dimensional disorder. This means that someone with IED isn’t just on the far end of the aggressive continuum. It is a discrete condition.

It is a discrete condition.

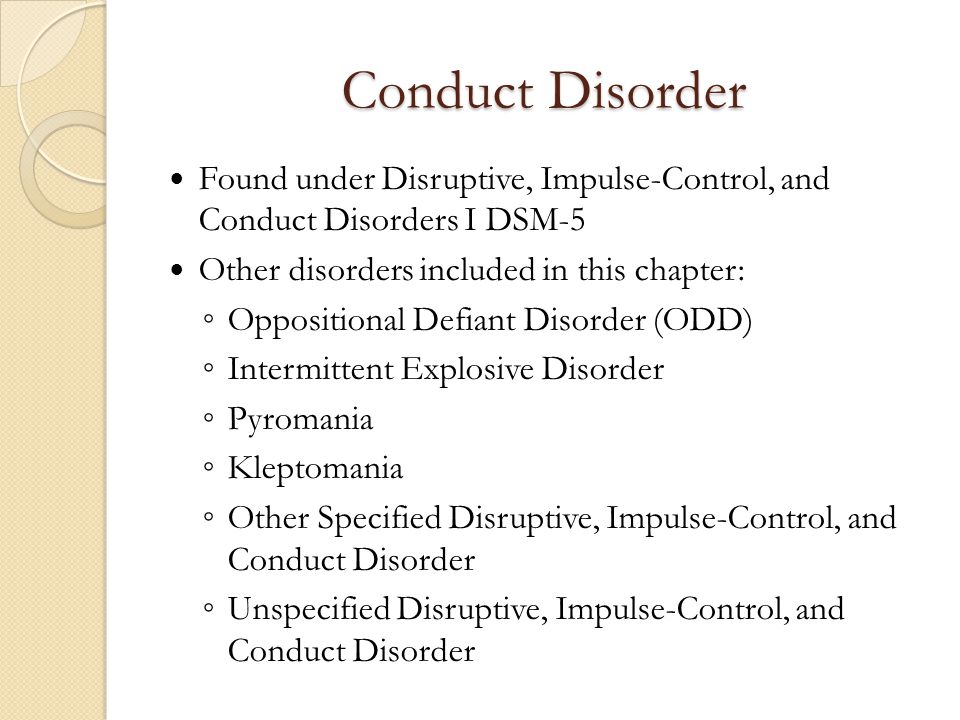

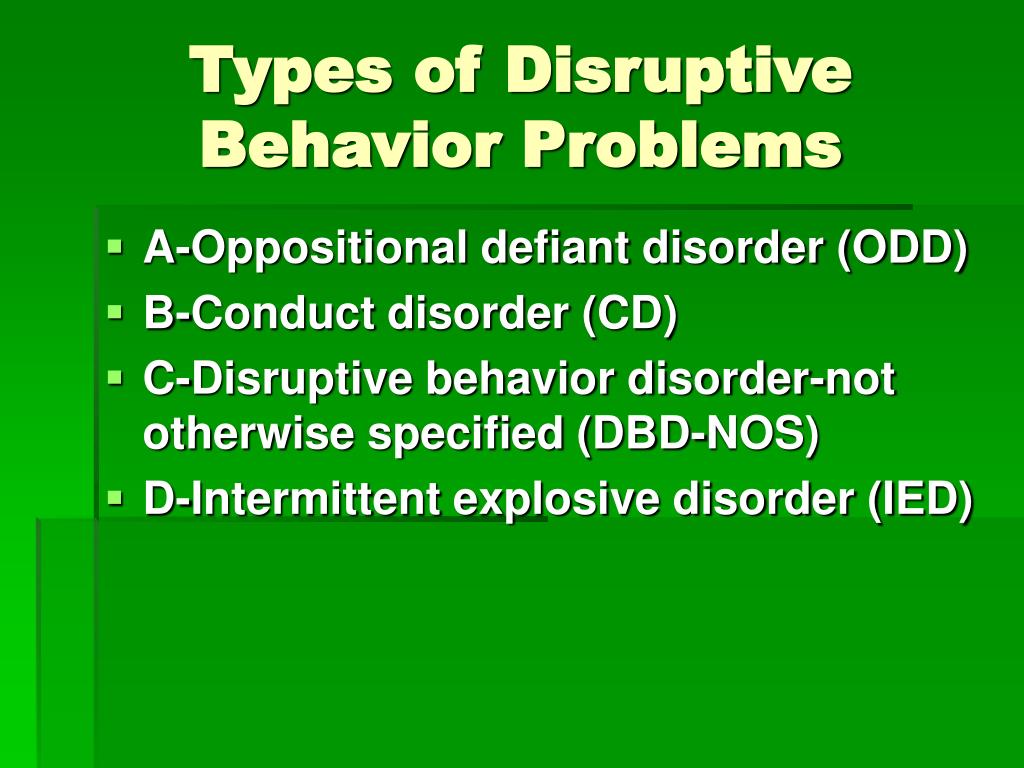

To be more specific, IED is considered one of the five impulse control disorders, a family which also includes oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder, kleptomania, and pyromania.

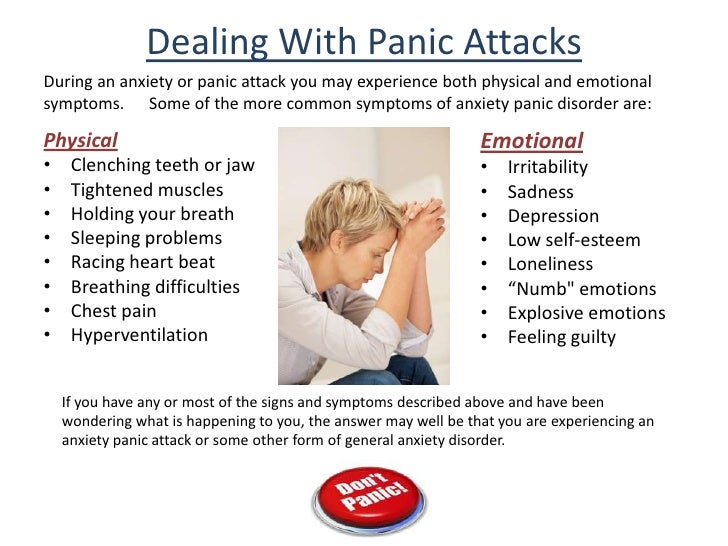

Is Intermittent Explosive Disorder a Mood Disorder?Intermittent explosive disorder is not a mood disorder — however, mood disorders like anxiety and depression do often co-occur (four times more prevalent in people with IED). In addition, substance abuse is common (three times more prevalent in people with IED).

What Is the Difference Between Disruptive Mood Dysregulation and Intermittent Explosive Disorder?Disruptive mood dysregulation is a mood disorder characterized by intense angry outbursts in children between the ages of 6 and 18 years, with symptoms typically starting before the age of 10.

The biggest difference between disruptive mood dysregulation and intermittent explosive disorder is that the former involves an irritable or angry mood most of the day, nearly every day. Remember: Intermittent explosive disorder is characterized by sudden angry episodes.

Remember: Intermittent explosive disorder is characterized by sudden angry episodes.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), signs and symptoms of an intermittent explosive disorder episode include:

- Yelling

- Intense arguments

- Road range

- Physical violence

- Damaging property

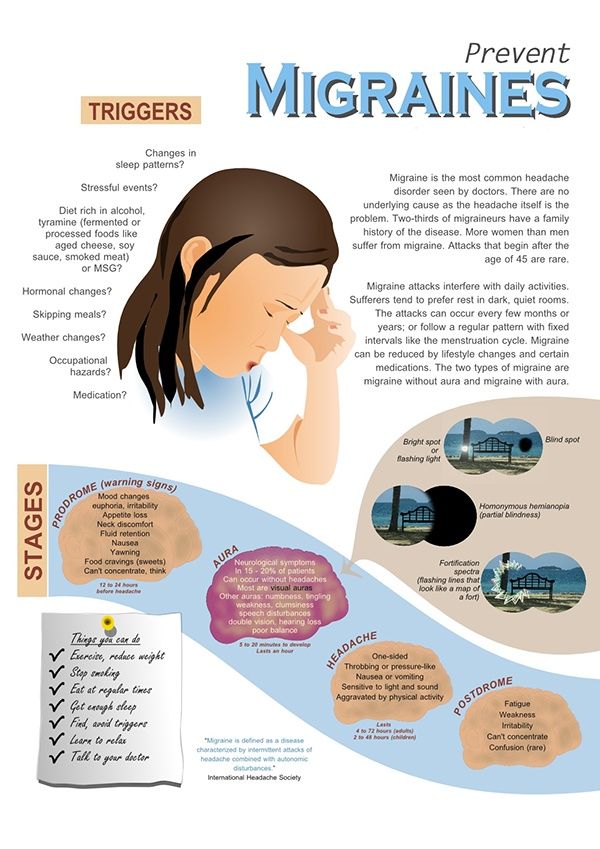

Those with IED might also experience headaches, muscle tension, heart palpitations, tremors, and an increase in energy before and during their episode. Once their outburst is over, they might feel relieved and/or tired. And later, regretful or embarrassed by their behavior.

How Do You Know If You Have Intermittent Explosive Disorder?If you or your friend have angry outbursts that involve the above signs and symptoms, you might have intermittent explosive disorder. Some people with IED have these episodes regularly, while others go for weeks or months without having an outburst.

Some people with IED have these episodes regularly, while others go for weeks or months without having an outburst.

The only way to know for sure if you have intermittent explosive disorder is to see a mental health professional. They can observe your symptoms, make a diagnosis, and then create a personalized treatment plan for you that’ll help you successfully manage your disorder.

What Causes IED? Is Intermittent Explosive Disorder Genetic?Like many psychiatric conditions, intermittent explosive disorder can be caused by a combination of neurological, genetic, and environmental factors. IED can first be diagnosed at age six and it usually peaks in mid-adolescence.

Most neurological research into the condition implicates serotonin abnormalities and difficulties in regulatory control of the prefrontal cortex. Psychological testing shows that people with IED have stronger amygdala reactions to angry faces. They also make more mistakes on the Stroop test, which measures cognitive interference.

In addition, risk factors for intermittent explosive disorder include:

- Exposure to violence or explosive behavior as a kid

- Being male (intermittent explosive disorder is more common in men than women)

- Experiencing physical or emotional trauma (research has shown a strong link between childhood trauma and IED)

- Having a history of substance abuse

- Having other medical conditions

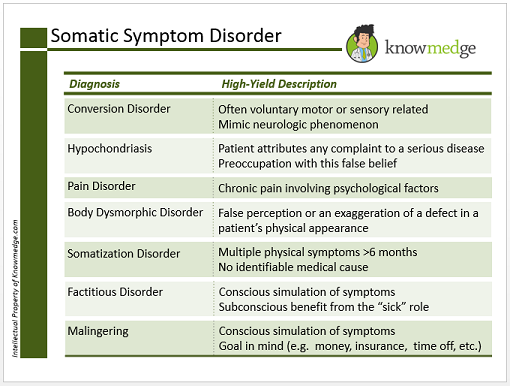

IED is frequently misdiagnosed, leading to inadequate treatment, so it’s helpful to understand what IED is not. First, it is not bipolar disorder: Some research suggests that IED and bipolar disorder can co-occur at high rates, but they are not the same thing. For example, someone with bipolar disorder exhibits far more mood symptoms than someone with IED. Both disorders, however, may involve brain regions that regulate top-down control of aggression and violent behavior.

To diagnose IED, mental health professionals need to rule out other possible causes of the behavior, too. For example:

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). As discussed earlier, IED is characterized by brief, unprovoked episodes rather than pervasive and persistent emotions that might indicate a mood disorder like DMDD.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Aggressive behavior can also be a symptom of PTSD, but PTSD is dimensional, not taxonic in nature. The comorbidity of these two disorders may lead to worse outcomes.

- Rageaholism. Being a “rageaholic” is not a medical diagnosis.

- Personality disorder. Mental health disorders like antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder are also dimensional, not taxonic. Someone with IED might also have a personality disorder, but the two diagnoses are distinct.

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD).

Someone with ODD might lose their temper and suffer psychosocial consequences, but their hostility is typically more directed at authority figures.

Someone with ODD might lose their temper and suffer psychosocial consequences, but their hostility is typically more directed at authority figures. - Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Someone with ADHD might show affective intensity and lability, but ADHD doesn’t cause serious aggression.

First, it’s important that you know you are not responsible for de-escalating an angry person. They must take responsibility for their own emotional and behavioral health. That said, if someone you care about has intermittent explosive disorder and you want to help during their outbursts, you can utilize specific de-escalation techniques.

Effective de-escalation requires patience and calm. As much as you can, try to disengage from your personal feelings during the episode. It may be helpful to recognize the IED person’s behavior as out of their control.

People with IED may have incredibly intense emotions, immature defense mechanisms (like projection and denial), and poor reality testing. This can all make it nearly impossible to deal with them rationally. So instead, you defuse. Here are some specific de-escalation techniques that might prove useful during IED outbursts:

This can all make it nearly impossible to deal with them rationally. So instead, you defuse. Here are some specific de-escalation techniques that might prove useful during IED outbursts:

- Use tactful language rather than belittling the person.

- Don’t invade the person’s personal space, but stay close enough to build rapport.

- Use shared problem-solving tactics to affirm the person’s feeling of autonomy. For example, say, “What can we do to fix this?”

- Don’t deliver ultimatums or engage in power struggles.

- Validate the person’s anger. They’re allowed to express their feelings as long as they’re not harming themselves or others.

- Suggest face-saving alternatives to their aggression, like a cooling-off period.

- Use active listening skills, which show that you’re positively engaged.

- Offer empathetic statements, like, “It sounds like you’re really hurt.

”

” - Don’t relitigate what happened or who was at fault. Keep returning to potential solutions to the problem.

- Use deliberately calm body language and a soothing tone of voice. Don’t feed the drama.

- Use positive reinforcement when the person regains control.

If you feel threatened, you’ll need to take a firmer approach. You may need to shift your supportive stance to a control stance and/or remove yourself to a safe area.

An intimate partner of someone with IED may be familiar with the person’s emotional triggers and be able to recognize the signs that an outburst is coming. For example, the person with IED might shake, experience tightness in their chest, or start to become agitated. But this doesn’t mean that a partner has the luxury of avoiding the episode. In fact, they may be the first line of defense.

For a loved one, acute IED outbursts might feel like emotional tyranny. The person may become verbally or physically abusive, which is never okay in an intimate relationship. To keep yourself safe, eliminate access to weapons or dangerous objects that the person might use to harm themselves or others. Devise an escape plan that you can enact if you feel threatened.

To keep yourself safe, eliminate access to weapons or dangerous objects that the person might use to harm themselves or others. Devise an escape plan that you can enact if you feel threatened.

Unfortunately, only a minority of people with IED receive treatment. They may never recognize the negative consequences of the explosive episodes they’re unable to control. If the person you love isn’t willing to admit they have a problem and work on mitigating their impulsive aggressive behavior, you may need to protect yourself by leaving the situation for good.

Intermittent Explosive Disorder TreatmentLike many other mental disorders, intermittent explosive disorder treatment often involves prescription medication — particularly SSRIs like fluoxetine — and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Intermittent explosive disorder medication: Antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, and mood regulators are commonly prescribed for intermittent explosive disorder. Fluoxetine — a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), which is an antidepressant — is the most studied and research-backed medication for treating IED.

Fluoxetine — a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), which is an antidepressant — is the most studied and research-backed medication for treating IED.

Therapy for intermittent explosive disorder: Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) includes coping skills training, relaxation training, and cognitive restructuring that has been shown to reduce anger, automatic thoughts, and impulsive behavior.

Can Intermittent Explosive Disorder Be Cured?No, intermittent explosive disorder cannot be cured. However, it can be successfully treated with medication and therapy, as outlined above. Treatment is focused on helping those with IED to better regulate or manage their angry outbursts.

Intermittent Explosive Disorder TestIf you’re concerned that someone you know might have symptoms of intermittent explosive disorder, they can complete an intermittent explosive disorder test here.

If your concerns remain, a mental health professional can administer a full IED screening questionnaire (IED-SQ) and develop an individualized treatment plan. Remember: A diagnosis is not an identity. In most cases, it’s the first step toward recovery.

Remember: A diagnosis is not an identity. In most cases, it’s the first step toward recovery.

Intermittent Explosive Disorder: Symptoms & Treatment

Overview

What is intermittent explosive disorder?

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is a mental health condition marked by frequent impulsive anger outbursts or aggression. The episodes are out of proportion to the situation that triggered them and cause significant distress.

People with intermittent explosive disorder have a low tolerance for frustration and adversity. Outside of the anger outbursts, they have normal, appropriate behavior. The episodes could be temper tantrums, verbal arguments or physical fights or aggression.

Intermittent explosive disorder is one of several impulse control disorders.

Approximately 80% of people with IED have another mental health condition, with anxiety disorders, externalizing disorder, intellectual disabilities, autism and bipolar disorder being the most common.

Who does intermittent explosive disorder affect?

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) can affect children aged 6 years and older and adults. Adults diagnosed with IED are usually younger than 40 years old.

IED more commonly affects people assigned male at birth (AMAB) than people assigned female at birth (AFAB).

How common is intermittent explosive disorder?

Researchers estimate that approximately 1.4% to 7% of people have intermittent explosive disorder.

Symptoms and Causes

What are the signs and symptoms of intermittent explosive disorder?

The main sign of intermittent explosive disorder is a pattern of outbursts of anger that are out of proportion to the situation or event that caused them. People with IED are aware that their anger outbursts are inappropriate but feel like they can’t control their actions during the episodes.

The aggressive outbursts:

- Are impulsive (not planned).

- Happen rapidly after being provoked.

- Last no longer than 30 minutes.

- Cause significant distress.

- Cause problems at school, work and/or home.

Examples of how the anger manifests include:

- Temper tantrums.

- Verbal arguments, which may include shouting and/or threatening others.

- Physically assaulting people or animals, such as shoving, slapping, punching or using a weapon to cause harm.

- Property/object damage, such as throwing, kicking or breaking objects and slamming doors.

- Domestic violence.

- Road rage.

The anger episodes can be mild or severe. They may involve hurting someone badly enough to require medical attention or even cause death.

If you have IED, right before an anger outburst, you may experience:

- Rage.

- Irritability.

- An increasing sense of tension.

- Racing thoughts.

- Poor communication.

- Increased energy.

- Tremors.

- Heart palpitations.

- Chest tightness.

After an outburst, you may feel a sense of relief, followed by regret and embarrassment.

What causes intermittent explosive disorder?

Researchers are still trying to discover the exact cause of intermittent explosive disorder, but they think genetic, biological and environmental factors contribute to its development:

- Genetic factors: IED more commonly runs in biological families. Studies suggest that 44% to 72% of the likelihood of developing impulsive aggressive behavior is genetic.

- Biological factors: Studies show that brain structure and function are altered in IED. For example, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies suggest that it affects the amygdala, which is the part of your brain involved in emotional functioning. In addition, studies show that the level of serotonin (a neurotransmitter and hormone) is lower than normal in people with IED.

- Environmental factors: Experiencing verbal and physical abuse in childhood and/or witnessing abuse during childhood appears to play a role in the development of IED.

Having experienced one or more traumatic events in childhood also seems to play a role.

Having experienced one or more traumatic events in childhood also seems to play a role.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is intermittent explosive disorder diagnosed?

If you think you or your child may have intermittent explosive disorder, it’s important to talk to your healthcare provider. They’ll likely refer you to a mental health professional who’s experienced in diagnosing IED.

A licensed mental health professional — such as a psychiatrist, psychologist or clinical social worker — can diagnose IED based on the diagnostic criteria for it in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

They do so by performing a thorough interview and having conversations about symptoms. They ask questions that’ll shed light on:

- Personal medical history and biological family medical history, especially histories of mental health conditions.

- Relationship history.

- School or work history.

- Impulse control.

Your mental health professional may also work with your family and friends to collect more insight into your behaviors and history.

To receive an intermittent explosive disorder diagnosis, you must display a failure to control aggressive impulses as defined by either of the following:

- High frequency/low intensity episodes: Verbal aggression (temper tantrums, verbal arguments or fights) or physical aggression toward property, animals or people, occurring twice weekly, on average, for three months. The aggression doesn’t result in physical harm to people or animals or the destruction of property.

- Low frequency/high intensity episodes: Three episodes involving damage or destruction of property and/or physical assault involving physical injury against animals or other people occurring within a 12-month period.

The degree of aggression displayed during the outbursts must be greatly out of proportion to the situation. In addition, the outbursts aren’t pre-planned. They’re impulse- and/or anger-based. Your mental health professional will also make sure that the outbursts aren’t better explained by another mental health condition, medical condition or substance use disorder.

In addition, the outbursts aren’t pre-planned. They’re impulse- and/or anger-based. Your mental health professional will also make sure that the outbursts aren’t better explained by another mental health condition, medical condition or substance use disorder.

People must be at least 6 years old to get an IED diagnosis, but it’s usually first observed in late childhood or adolescence.

Management and Treatment

How is intermittent explosive disorder treated?

Treatment for intermittent explosive disorder typically involves psychotherapy (talk therapy) focused on changing thoughts related to anger and aggression. Treatment may also include medication, depending on your age and symptoms.

The goal of treatment for IED is remission, which means that your symptoms (anger outbursts) go away or you experience improvement to the point that only one or two symptoms of mild intensity persist. For people who don’t achieve remission, a reasonable goal is stabilizing the safety of the person and others, as well as a substantial improvement in the number, intensity and frequency of anger outbursts.

Psychotherapy for IED

Psychotherapy (talk therapy) is usually the main treatment for intermittent explosive disorder, especially cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

CBT is a structured, goal-oriented type of therapy. A therapist or psychologist helps you take a close look at your thoughts and emotions. You’ll come to understand how your thoughts affect your actions. Through CBT, you can unlearn negative thoughts and behaviors and learn to adopt healthier thinking patterns and habits.

CBT teaches people with IED how to manage negative situations in day-to-day life and may thus prevent aggressive impulses that can trigger explosive outbursts.

Specific techniques mental health professionals use in CBT for intermittent explosive disorder include:

- Cognitive restructuring: This involves changing faulty assumptions and unhelpful thoughts about frustrating situations and perceived threats.

- Relaxation training: Relaxing techniques like deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation (tensing and relaxing different muscle groups while imagining situations that provoke anger) can help minimize your response to triggering situations.

- Coping skills training: This involves role-playing situations that may cause an explosive episode and practicing healthy responses like walking away.

- Relapse prevention: This involves educating people with IED that recurrence of impulsive aggressive behavior is common and should be viewed as a lapse or “slip” rather than a failure.

Medications for IED

Certain medications may increase the threshold (level) at which a situation triggers an angry outburst for people with intermittent explosive disorder.

Fluoxetine (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, or SSRI) is the most studied medication for treating intermittent explosive disorder. Other medications that have been studied for IED include phenytoin, lithium, oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine.

In general, healthcare providers typically prescribe the following classes of medications for IED:

- Antidepressants.

- Antipsychotics.

- Anticonvulsants.

- Antianxiety medications.

- Mood regulators.

Prevention

What are the risk factors for developing intermittent explosive disorder?

Risk factors for intermittent explosive disorder include:

- Being a young person AMAB.

- Being unemployed.

- Being single (unmarried).

- Having lower levels of education.

- Experiencing physical or sexual violence, especially as a child.

- Having biological family members with intermittent explosive disorder.

If you’re concerned about your child’s risk of developing intermittent explosive disorder, talk to your healthcare provider.

Outlook / Prognosis

What is the prognosis (outlook) for intermittent explosive disorder?

People with intermittent explosive disorder tend to have poor life satisfaction and lower quality of life. It can have a very negative impact on your health and can lead to severe personal and relationship problems.

Cognitive therapy and medication can successfully manage IED. However, according to studies, IED appears to be a long-term condition, lasting from 12 to 20 years or even a lifetime.

However, according to studies, IED appears to be a long-term condition, lasting from 12 to 20 years or even a lifetime.

Having intermittent explosive disorder makes it more likely that you’ll develop the following conditions:

- Depression.

- Anxiety.

- Alcohol use disorder.

- Substance use disorder.

In addition, people with IED are at an increased risk for self-harm (self-injury) and suicide. Because of this, it’s essential to seek medical help as soon as possible if you feel you or a family member has intermittent explosive disorder.

Living With

How do I take care of myself if I have intermittent explosive disorder?

If you have intermittent explosive disorder, it’s essential to seek professional, medical treatment. You’ll learn a variety of coping techniques in therapy. These can help prevent anger episodes. They include:

- Relaxation techniques.

- Changing the ways you think (cognitive restructuring).

- Communication skills.

- Learning to change your environment and leaving stressful situations when possible.

It’s also very important to avoid alcohol and recreational drugs. These substances can increase the risk of violent behavior.

When should I see my healthcare provider for intermittent explosive disorder?

If you or your child has been diagnosed with intermittent explosive disorder, you’ll need to see your healthcare team regularly to make sure your treatment (talk therapy and/or medication) is working.

If you or your child displays behavior that harms or endangers others, such as other people or animals, it’s important to find immediate care.

People with intermittent explosive disorder who are thinking of harming themselves or attempting suicide need help right away.

If you or someone you know is in immediate distress or is thinking about hurting themselves, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline toll-free at 1.800. 273.TALK (8255).

273.TALK (8255).

A note from Cleveland Clinic

It’s important to remember that intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is a mental health condition. As with all mental health conditions, seeking help as soon as symptoms appear can help decrease the disruptions to your life. Mental health professionals can offer treatment plans that can help you manage your thoughts and behaviors.

The family members and loved ones of people with IED often experience stress, depression and isolation. It’s important to take care of your mental health and seek help if you’re experiencing these symptoms. If you’re in a relationship with someone who has intermittent explosive disorder, take steps to protect yourself and your children.

what it is and how to treat it

Impulsive aggression is not intentional and is defined as a disproportionate reaction to any provocation, real or imagined.

Some people report pre-explosion affective changes (eg, tension, mood changes).

Intermittent explosive disorder is currently classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a destructive disorder of impulse and behavior control.

It is not easy to characterize on its own and often co-occurs with other mood disorders, especially bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder.

Individuals diagnosed with IED report that their flare-ups are brief (lasting less than an hour), with various bodily symptoms (sweating, stuttering, chest tightness, spasms, palpitations) reported by a third of the samples.

Aggressive acts were reported to be often accompanied by feelings of relief and, in some cases, pleasure, but often accompanied by remorse.

This disorder causes great psychological distress and can lead to: stress, social and family difficulties, economic difficulties and legal difficulties.

Outbursts of anger have a serious impact on the patient's life and disrupt social, work, financial and legal activities.

This behavior can lead to serious problems at school and work, as well as civil lawsuits as a result of fights and arguments.

Such patients often also have mood disorders, fears and phobias, eating disorders, high levels of alcohol abuse, personality disorders such as antisocial or borderline personality disorder, and other specific impulse control disorders.

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) usually begins quite early in life and is more common in men than women.

In 80% of cases it persists for a long time.

Its incidence is about 5%-7%.

SVU is diagnosed when a patient has three or more episodes of anger per year.

The difference between obsessive and impulsive

Compulsiveness is when a person has an irresistible desire to do something.

Impulsivity is when a person acts according to his instincts.

The key difference between these two forms of behavior is that in compulsive behavior the person thinks about the action, while in impulsive behavior the person simply acts without thinking.

Both concepts are treated in abnormal psychology in the context of psychological disorders.

Abnormal psychology also pays attention to impulsive disorders.

Impulsive behavior gives a person pleasure because it reduces stress.

Those with impulsive disorders do not think about the act, but participate in the moment when it comes to them.

According to psychologists, impulsive disorders are most often associated with negative consequences, such as illegal actions.

Gambling, risky sexual behavior and drug use are some of these examples.

Inability to resist aggression, kleptomania, pyromania, trichotillomania (hair pulling) are some impulsive disorders.

This shows that compulsiveness and impulsivity are two different behaviors.

Behavior indicating lack of control over anger

- verbal aggression (insults, fights and threats)

- physical aggression towards animals or people (injury or bodily harm, destruction of objects and property)

Intermittent explosive disorder symptoms and consequences

Symptoms that precede or accompany aggressive events,

- irritability

- mental arousal

- great energy and strength

- thought acceleration

- tingling and shivering

- heartbeat and pressure in head and chest

- the feeling of listening to an echo.

The voltage disappears as soon as it is reached.

IED treatment

IED treatment is selected individually.

This usually includes pharmacological and therapeutic treatments to change behavior and gain more control over aggressive impulses.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been found to help the patient explore the mental regulation of explosive outbursts, using relaxation and cognitive corrective techniques to alter the patient's response to triggers.

Article written by Dr. Letizia Ciabattoni

See also:

Emergency Live More... Live: download your newspaper's new free app for IOS and Android

Trichotillomania, or compulsive hair-pulling and hair-pulling disorder

Impulse control disorders: kleptomania

Impulse control disorders: ludopathy or gaming disorder 9003

source:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12096933

https://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3105561/

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3105561/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3637919/

https://convegnonazionaledisabilita.it/relazioni/2018/NOLLI%20MARIELLA%20EMILIA%20-%20Trattamento%20funzionale%20dell_aggressivita %cc%80.pdf

https://www.lumsa.it/sites/default/files/UTENTI/u474/lezione%20psicopatologia%2014.pdf

Impulsivity and Compulsivity: Emergent Psychopathology, Luigi Janiri, F. Angeli , 2006

McElroy SL, riconoscimento e trattamento DSM-IV intermittent disorder, in J Clin Psychiatry, 60 Suppl 15, 1999, pp. 12-6, PMID 10418808

McElroy S.L., Sutullo C.A., Beckman D.A., Taylor P., Keck P.E., DSM-IV intermittent violation of Esplosivo Intermittente: un rapporto di 27 case, in J Clin Psychiatry, vol. 59, n. 4, April 1998, pp. 203–10; quiz 211, DOI: 10.4088/JCP.v59n0411, PMID 9590677

Tamam L., Eroglu M., Paltaji O. (2011). Disturbo esplosivo intermittent. Appprocci attuale in Psichiatria, 3(3). 387-425

Diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder - Drink-Drink

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is a mental disorder that causes repetitive, sudden episodes of violent or aggressive behavior. The behavior is described as disproportionate.

The behavior is described as disproportionate.

Although the cause of IED is not fully understood, it is likely related to factors such as genetics and structural differences in the brain. Many people with IED also grew up in a hostile family environment.

Because little is known about this condition, there is no test for intermittent explosive disorder. But a mental health professional can diagnose IED based on physical and psychological assessments.

In this article, we will look at what a mental health professional looks for, as well as the criteria for an official diagnosis of IED.

Is there a test for "anger disorder"?

There is no test for Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED), which is a fairly new diagnosis. It was first introduced as a mental disorder in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1980.

But there is a condition screening tool.

This tool, called the IED Screening Questionnaire (IED-SQ), can assess the risk of developing IED. It can also help detect symptoms and determine if further evaluation is needed.

It can also help detect symptoms and determine if further evaluation is needed.

However, IED-SQ does not provide an official diagnosis. It only determines the likelihood that your symptoms are due to IEDs.

Intermittent Explosive Disorder Diagnosis

IED is diagnosed by a mental health professional. They will use numerous methods to make a diagnosis.

This will likely include:

- Medical history. To understand your physical and psychiatric history, your doctor will ask for information about your medical history.

- Physical examination . A general practitioner will look for possible physical causes of your symptoms. Your physical examination may include blood tests.

- Psychological assessment . You will discuss your behavior, emotions and thoughts. This allows the mental health professional to rule out other mental illnesses.

Your mental health professional will then compare your symptoms to criteria in the most recent edition of the DSM (DSM-5). You will be diagnosed with IED if you experience one of the following:

You will be diagnosed with IED if you experience one of the following:

- verbal or physical aggression towards things, animals, or other people, twice a week (on average), for 3 months, without causing physical harm or injuries

- three violent outbursts resulting in damage or injury within 12 months

According to DSM-5, a diagnosis of IED must also include outbreaks that:

- are not consistent with the situation

- are not explained by another psychiatric disorder, such as borderline personality disorder (BPD)

- are not related to illness or substance abuse

- impulsive and not related to another purpose, such as getting money

- cause distress or interfere with your ability to work or maintain relationships

Symptoms of intermittent explosive disorder

IED causes a wide range of symptoms. Before or during the IEV episode, you may have:

- Irritability

- Anges

- Racing thoughts

- Energy Energy

- Far Ballowing

- Breasts

- Tremor

This means that the potential consequences don't cross your mind. These actions may include:

This means that the potential consequences don't cross your mind. These actions may include: - Crumbing

- To argue for no reason

- Throwing items

- Start of the fight

- Threat to people

- Push or beat people

- Porption of property or things

- family

In adults, the episodes are often described as "adult temper tantrums". Each episode is usually less than 30 minutes long.

You may feel very tired or relieved after an episode. You may feel regret, guilt, or shame later.

Complications of intermittent explosive disorder

If you have IED, you are more likely to experience other complications, including:

- physical health problems such as high blood pressure and ulcers

- mood disorders, including depression and anxiety

- poor interpersonal relationships

- drug or alcohol abuse

- job loss

- school problems

- car collisions (from road rage)

- financial or legal problems

- self harm

- suicide

Emergency Medical Services

Call 911 right away if you think you could harm yourself or someone else.

When to see a doctor

If you are constantly angry for no reason, see a doctor. You should also seek help if your outbursts are preventing you from keeping a job or maintaining a stable relationship.

Your doctor may recommend a mental health professional to evaluate your symptoms.

If you find symptoms of IED in another adult, ask them (kindly) to see a specialist. A therapist or counselor can give you advice on how to talk to your loved one.

If you think your teen or child has an IED, take them to a mental health professional. A doctor may recommend family therapy as part of the treatment process.

Conclusion

Although there is no test for intermittent explosive disorder, a mental health professional can use a questionnaire to check your risk.

They can diagnose IEDs based on your:

- medical history

- physical exam

- psychological evaluation

See your doctor if you think you have IED.