Frequently asked questions about eating disorders

Frequently Asked Questions about Eating Disorders

Q: What are eating disorders?

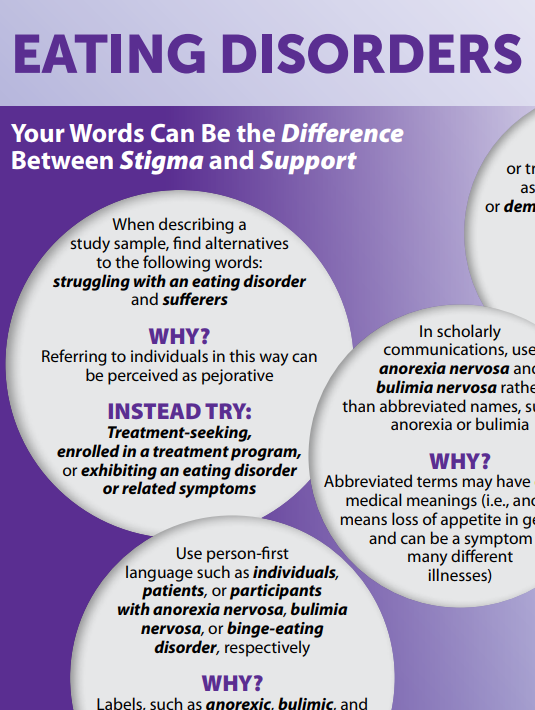

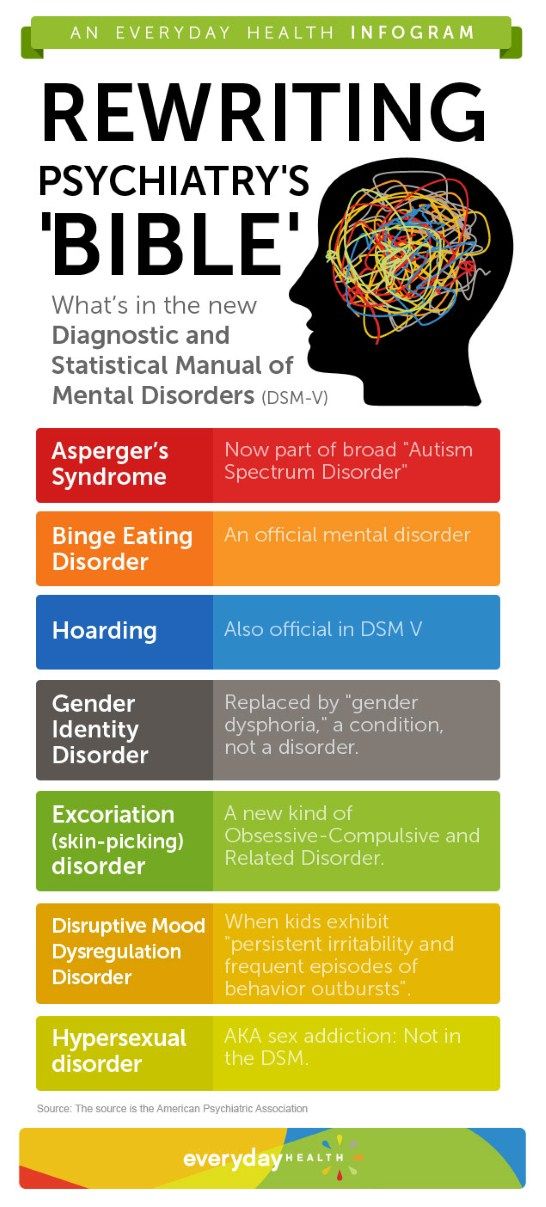

A: The main eating disorder categories include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, and other specified feeding or eating disorder.

The hallmark feature of anorexia nervosa is significantly low body weight, followed by an intense fear of gaining weight, and difficulty appreciating the health consequences of being underweight. Some individuals with anorexia nervosa engage in binge eating (i.e., eating large amounts of food while feeling out of control) and/or purging (i.e., trying to compensate for calories consumed through self-induced vomiting or inappropriate use of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications). Others do not binge or purge, but consume a very limited diet that does not adequately support their nutritional needs.

In contrast, individuals with bulimia nervosa are not underweight. Instead, bulimia nervosa is characterized by binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviors. Compensatory behaviors may include self-induced vomiting, laxative or diuretic abuse, fasting, or excessive exercise. A key feature of bulimia nervosa is that those who struggle base most of their self-worth on their current shape or weight, meaning that even minor fluctuations on the scale can produce dramatic shifts in self-esteem.

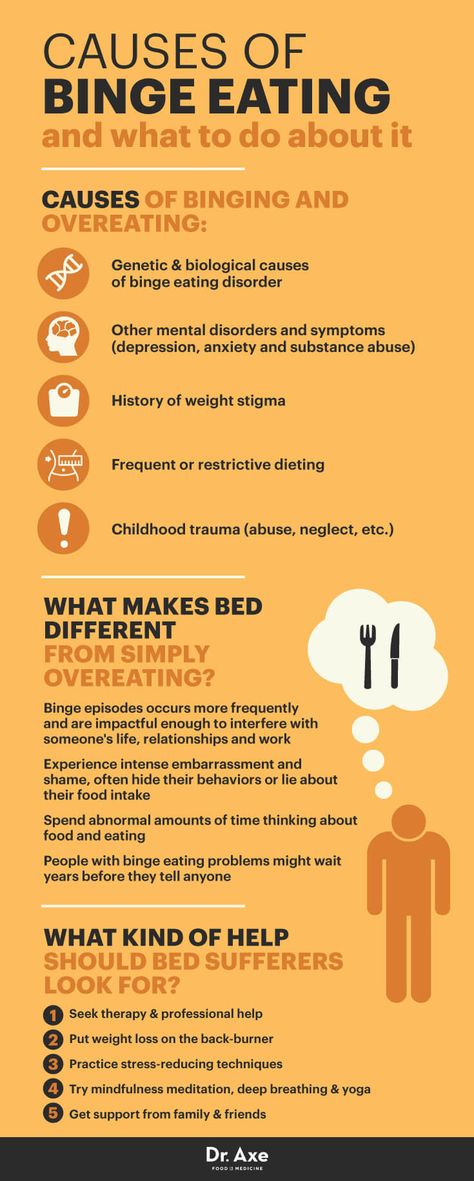

People with binge eating disorder frequently go on eating binges, but do not use inappropriate compensatory behaviors. This distinguishes binge eating disorder from bulimia nervosa. Experts agree that binge eating is not just having an extra helping of dessert on a holiday or other special occasion. Rather, binge eating involves eating an unusually large amount of food (someone else observing would agree that the amount was large) in a discrete period of time, and feeling as though it is hard to control the eating behavior (i.e. , it's hard to stop even though you really want to). People with binge eating disorder typically feel very distressed about their pattern of eating.

, it's hard to stop even though you really want to). People with binge eating disorder typically feel very distressed about their pattern of eating.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder is a newly recognized eating disorder in which limited dietary intake leads to weight loss, inadequate growth, or nutritional deficiency. Rather than experiencing an intense fear of weight gain (as in anorexia nervosa), individuals with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder show little interest in feeding, avoid specific foods due to a feeding-related traumatic event (e.g., gagging or choking), or avoid foods with specific sensory qualities (e.g., texture, taste, temperature).

Other specified feeding or eating disorder is a term for eating disorders of clinical severity that cause impairment but cannot be captured by any of the official eating disorder categories. Individuals with other specified feeding or eating disorder are just as deserving of treatment as those with the official recognized diagnoses described above. Examples include atypical anorexia nervosa (anorexic features without low body weight), subthreshold bulimia nervosa (bingeing and purging less than once per week or for less than three months), subthreshold binge eating disorder (binge eating less than once per week or for less than three months), purging disorder (vomiting, laxative misuse, or diuretic misuse in the absence of binge eating), and night eating syndrome (a pattern of nocturnal eating that causes distress).

Examples include atypical anorexia nervosa (anorexic features without low body weight), subthreshold bulimia nervosa (bingeing and purging less than once per week or for less than three months), subthreshold binge eating disorder (binge eating less than once per week or for less than three months), purging disorder (vomiting, laxative misuse, or diuretic misuse in the absence of binge eating), and night eating syndrome (a pattern of nocturnal eating that causes distress).

Q: What are other types of eating and feeding difficulties?

A: People with rumination disorder struggle with recurrent food regurgitation for at least one month. This is different from self-induced vomiting, because the regurgitation of food comes back up into the mouth effortlessly, but still could be voluntary.. After regurgitating, individuals with rumination disorder typically re-chew, re-swallow, or spit out the previously ingested food. Rumination disorder is also different from esophageal reflux and other gastrointestinal conditions, which can be verified by physical examination or other testing.

Individuals with pica eat non-nutritive, non-food substances, such as paper, cloth, or dirt. Food that isn’t typically eaten on its own or are eaten differently, such as cornstarch, ice, or uncooked pasta, aren’t considered for a diagnosis of pica, but this behavior could still could be impairing and require support to stop. Eating non-food substances for cultural or religious reasons would not qualify for a diagnosis of pica, nor would developmentally normal mouthing behaviors in young children (i.e., under the age of two).

Q: How common are eating disorders?

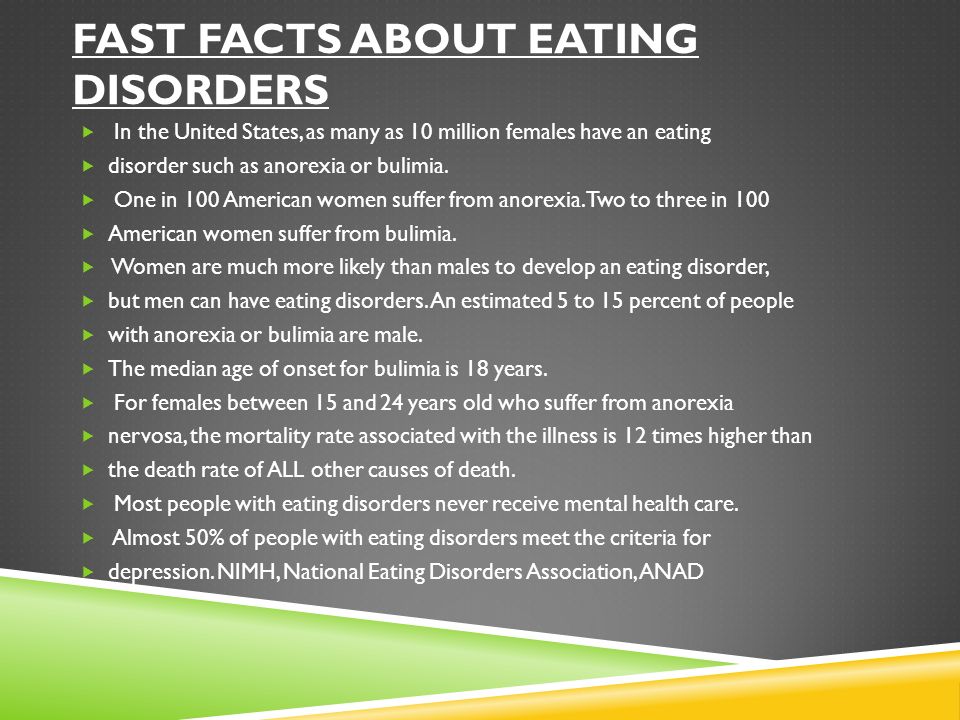

A: Eating disorders affect millions of people at any given point in time. Rates of eating disorders are particularly high among females between the ages of 12 and 35. Estimates indicate that approximately 0.5 to 3.7% of females have anorexia in their lifetime, while 1.1 to 4.2% of females experience bulimia and 2-5% of men and women have binge eating disorder in their lifetime. Importantly, individuals might struggle with a certain eating or feeding disorder (different types described above) at one point in time, but then develop symptoms of another eating or feeding disorder later. Reports show that migration between symptoms and behaviors over time can be common in eating disorders.

Importantly, individuals might struggle with a certain eating or feeding disorder (different types described above) at one point in time, but then develop symptoms of another eating or feeding disorder later. Reports show that migration between symptoms and behaviors over time can be common in eating disorders.

Our culture is keenly aware of body weight and shape, and concerns begin early in life, as reflected by reports that 40-60% of high school girls diet, and 13% of high school girls purge. Eating disorders most often develop during adolescence or early adulthood, but there are some reports of onset in early childhood and older adulthood. Eating disorders have long been thought of as problems affecting affluent white females. Although the prevalence of eating disorders in other socio-demographic groups is lower, we are seeing an increase in eating disorders among males and individuals from a variety of socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. The specific nature of the eating disturbance, as well as protective and risk factors, may vary, but the distress and impact on functioning occurs across gender and culture. It is estimated that approximately 5-15% of people with anorexia or bulimia and 35% of people with binge eating disorder are male.

It is estimated that approximately 5-15% of people with anorexia or bulimia and 35% of people with binge eating disorder are male.

Q: What causes an eating disorder?

A: This is an excellent question, and one that does not have an easy answer. Therefore, if you or your child struggles with an eating disorder, please do not blame yourself! Over the years, our understanding of the underlying cause of eating disorders has changed significantly. Eating disorders were once thought to be found only in high-achieving, affluent, Caucasian teenagers with demanding families. Adolescent girls were thought to starve themselves to prevent the body changes and social expectations associated with becoming a woman. Now, we believe that eating disorders are related to a combination of biologic, psychologic and social factors. They affect men and women of every age, socioeconomic, ethnic and cultural group.

Eating disorders are associated with other psychiatric illnesses such as substance use disorder, depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Like other psychiatric illnesses, they tend to run in families, which suggests an underlying genetic component. Eating disorders typically arise during life transitions (puberty, starting college, getting married, childbearing, changing jobs), or other stressful events (moving, death in family, divorce, loss of significant relationship, trauma or abuse). Sometimes, there are clear family problems that contribute to the development of an eating disorder. At other times, they arise in people with very loving, supportive families. Finally, cultural and societal expectations of beauty, which are perpetuated by the media, can lead to negative body image, which can in turn lead to disordered eating and exercise. For most people struggling with an eating disorder, several of the above factors converge to cause eating disorder symptoms. Effective treatment often involves teasing apart the underlying factors, and targeting each with an appropriate intervention.

Like other psychiatric illnesses, they tend to run in families, which suggests an underlying genetic component. Eating disorders typically arise during life transitions (puberty, starting college, getting married, childbearing, changing jobs), or other stressful events (moving, death in family, divorce, loss of significant relationship, trauma or abuse). Sometimes, there are clear family problems that contribute to the development of an eating disorder. At other times, they arise in people with very loving, supportive families. Finally, cultural and societal expectations of beauty, which are perpetuated by the media, can lead to negative body image, which can in turn lead to disordered eating and exercise. For most people struggling with an eating disorder, several of the above factors converge to cause eating disorder symptoms. Effective treatment often involves teasing apart the underlying factors, and targeting each with an appropriate intervention.

Q: I'm worried that my child might have an eating disorder.

How can I talk to him or her about this?

How can I talk to him or her about this?A: It is important to approach your child in a calm, empathic and non-judgmental manner. Tell him or her that you've noticed a change in his or her weight, exercise patterns or attitudes toward food, and that you're concerned that there may be problem. It is important for your child to hear that you are interested in understanding what is going on rather than trying to blame him or her. Encourage your child to respond to your concerns. Ask what he or she would like you to do. If your child doesn't know how you can be helpful, offer to speak to her pediatrician, or to set up an evaluation with a mental health professional. If she is resisting help, or says that there is nothing to worry about, tell her that you are still worried, and would like a professional's advice. While adolescents can resist limits, they need them, and despite their protests they typically feel reassured that their parents are involved and concerned. If you ever become concerned about your child's safety, due to low weight, threats of self-harm or threats of harm to others, seek emergency care immediately.

If you ever become concerned about your child's safety, due to low weight, threats of self-harm or threats of harm to others, seek emergency care immediately.

Q: I think I have an eating disorder, but I feel embarrassed to tell my doctor about my symptoms. What should I do?

A: You are not alone. Many people struggling with an eating disorder feel too ashamed or embarrassed about it to tell anyone, including their doctors. Yet there are some important reasons not to let your embarrassment stop you from telling your physician or counselor.

First, because eating disorder symptoms can lead to many potentially serious and even life-threatening medical risks, it is necessary to obtain a careful medical examination. Second, letting a doctor or counselor know about an eating disorder is a crucial step in the recovery process. Research has shown that telling a doctor or counselor about an eating disorder is linked with a greater likelihood of getting treatment for it.

We offer the following suggestions to help you summon your courage to talk with your doctor or mental health professional. Keep in mind that doctors, nurses, and therapists have heard the eating disorder story many times before and are comfortable hearing detailed descriptions of the symptoms. If you do not feel you can trust your doctor, ask friends (maybe even someone who has been in your situation) or family members that you do trust for the names of providers they have found helpful. You might even consider bringing a friend or family member along to your appointment for support.

Q: One of my close friends has an eating disorder but won't get help. What can I do?

A: First of all, your friend is fortunate to have your friendship. It is impossible to force someone into treatment unless they are ready to get help. That being said, you can sit down with your friend and let her know that you have noticed that her eating patterns have changed, and that you are worried that she might have a problem with eating or exercise. It is important to approach the discussion in an empathic, non-shaming manner. Your friend may become angry or may accuse you of being jealous or wanting to make her fat. This may be very difficult to hear, but try not to take it personally.

It is important to approach the discussion in an empathic, non-shaming manner. Your friend may become angry or may accuse you of being jealous or wanting to make her fat. This may be very difficult to hear, but try not to take it personally.

Due to the underlying eating disorder, people who are struggling with poor self-esteem and distorted body image sometimes lash out at the people who care about them. If your friend responds in this manner, calmly tell her that you regret that she feels that way, but that you are concerned and want to find a way to help her. Remain available to her in case she changes her mind. If your friend agrees to get help, she should contact her primary care physician for referrals to a dietician and mental health clinician. If your friend is a child or teenager, you really need to let her parents know why you are concerned, so that they can help her. You should also find a family member, teacher or counselor to talk to so that you don't feel so alone with this problem.

Q: Do eating disorders cause medical problems?

A: Eating disorders are the psychiatric illnesses with the highest rates of medical complications, including death. Because eating disorders can be associated with severe physical problems, patients should be closely followed by a primary care physician or, if indicated, a medical specialist. Some of the complications are minor and bothersome, while others can be life threatening. The following paragraphs outline some common medical complications of eating disorders:

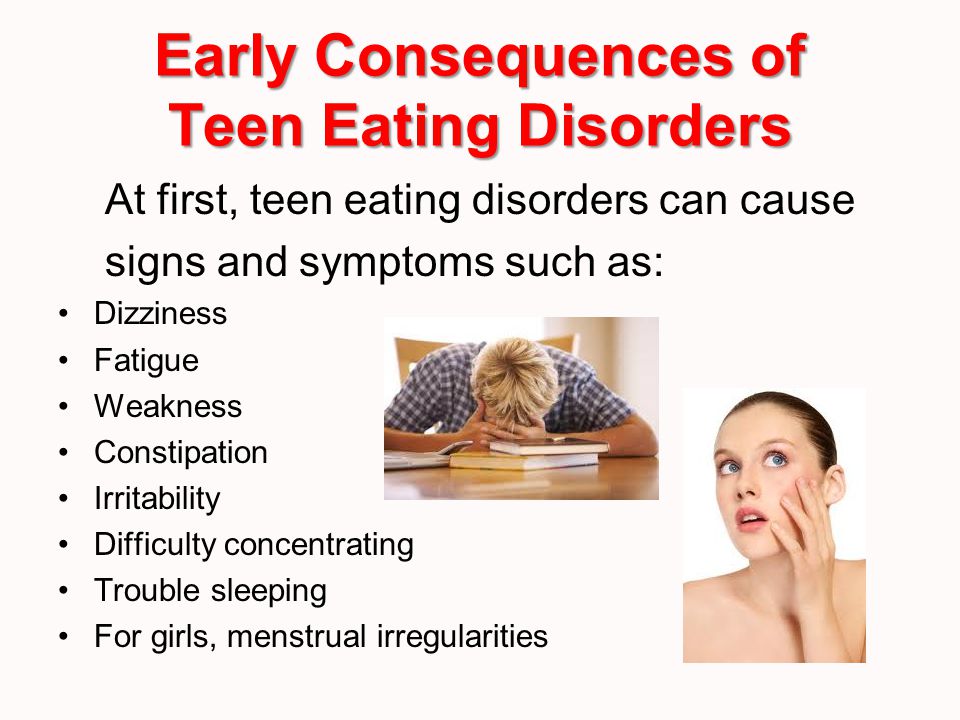

Symptoms Associated with Low Body Weight. Eating disorders can commonly be associated with weakness, inability to tolerate cold temperatures, and hair loss due to malnutrition and low body weight. Sometimes, because the body is trying to conserve energy, starvation can cause problems with thinking, poor concentration, poor energy, problems with sleeping, and loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities. These symptoms closely resemble depression, so it is important to have a mental health clinician evaluate the situation. The above symptoms will usually improve as nutritional status improves and weight is restored to a healthy range. Neuroendocrine complications such as bone loss and hormonal changes are common in eating disorders. About 90% of young women with anorexia nervosa suffer from bone loss, putting them at increased risk for fractures. "Osteopenia" is thinning of the bones and "osteoporosis" is severe thinning of the bones. Furthermore, when body weight is very low, patients will sometimes grow downy hair, called lanugo, on their body. This happens because there is not enough body fat present to insulate the body; it typically goes away as weight normalizes.

The above symptoms will usually improve as nutritional status improves and weight is restored to a healthy range. Neuroendocrine complications such as bone loss and hormonal changes are common in eating disorders. About 90% of young women with anorexia nervosa suffer from bone loss, putting them at increased risk for fractures. "Osteopenia" is thinning of the bones and "osteoporosis" is severe thinning of the bones. Furthermore, when body weight is very low, patients will sometimes grow downy hair, called lanugo, on their body. This happens because there is not enough body fat present to insulate the body; it typically goes away as weight normalizes.

In addition, many women with eating disorders experience changes in their menstrual periods. Their periods may become irregular, or may disappear completely. Some women have difficulty getting pregnant when they are struggling with eating problems. However, it is important to remember that one can still get pregnant, even when periods are irregular or absent, so it is important to continue to protect yourself against pregnancy if you do not wish to be pregnant. As nutritional status improves, periods will often become more regular, and fertility can be restored. Sometimes, a gynecologist or endocrinologist will be involved in treating these issues.

As nutritional status improves, periods will often become more regular, and fertility can be restored. Sometimes, a gynecologist or endocrinologist will be involved in treating these issues.

Dental and Gastrointestinal Complications. Stomach acid, which comes in contact with teeth during vomiting, can erode the enamel and can cause severe dental cavities. Patients who induce vomiting or experience effortless regurgitation should seek help from a dentist to prevent ongoing dental problems. Patients with eating disorders commonly report stomachaches or constipation, which can be related to dehydration, and lack of bulk in the diet. Again, these symptoms often resolve as the body gets used to refeeding and can also be treated by increasing fluid and fiber intake to a healthier range.

Metabolic and Cardiac Complications. Binge-eating can lead to obesity, which can subsequently lead to high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, and increased risk for cancer. Monitored, moderate weight loss and regular exercise can decrease the risk of each of these health problems. More severe medical side effects include life-threatening irregularities in heartbeat, which can cause cardiac arrest and sudden death. These are most commonly caused by abnormalities in electrolytes, such as potassium, which are necessary for the heart to beat properly. Vomiting and diarrhea, which often results from laxative or enema abuse, can lead to very low levels of potassium. Water pills can also cause electrolytes to become abnormal. However, it is important not to take potassium supplements unless directed to do so by your doctor, as high levels of potassium can also cause heart problems.

Monitored, moderate weight loss and regular exercise can decrease the risk of each of these health problems. More severe medical side effects include life-threatening irregularities in heartbeat, which can cause cardiac arrest and sudden death. These are most commonly caused by abnormalities in electrolytes, such as potassium, which are necessary for the heart to beat properly. Vomiting and diarrhea, which often results from laxative or enema abuse, can lead to very low levels of potassium. Water pills can also cause electrolytes to become abnormal. However, it is important not to take potassium supplements unless directed to do so by your doctor, as high levels of potassium can also cause heart problems.

Q: What are the most effective treatments for eating disorders?

A: Evidence-based outpatient treatments for eating disorders include cognitive-behavioral therapy, family-based treatment, and guided self-help. In some cases, a more intensive approach, such as inpatient hospitalization, is necessary. Learn more about levels of care for eating disorders.

Learn more about levels of care for eating disorders.

Learn more about our eating disorder treatment options at Mass General.

FAQS - Eating Disorders | Rosewood Centers

Speak to a Rosewood Specialist

(800) 845-2211

Common Questions About Eating Disorders

If you or someone you love is struggling with food or eating, you probably have lots of questions. Here are answers to commonly asked questions about eating disorders, including information about specific eating disorders such as anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorder. Accurate eating disorder information is important to recognizing when someone needs help, and can help you in making decisions about when to seek care.

What is eating disorder treatment?

Treatment from a multidisciplinary team of physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, dietitians, counselors whom treat the whole person suffering from eating disorders from a biological, nutritional, psychological, social, and spiritual approach. It’s a team approach from a group of specialists who have experience working with eating disorders. Treatment includes individual, group, and family therapy.

It’s a team approach from a group of specialists who have experience working with eating disorders. Treatment includes individual, group, and family therapy.

What Triggers Eating Disorders?

Eating disorders are complex diseases. Genetics and a family history of eating disorders, personality traits such as perfectionism, and psychological factors such as depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder and trauma are all associated with eating disorders. Other research indicates that some people with eating disorders have abnormalities in brain chemicals that regulate mood, stress, and appetite.

Social factors contribute as well. Research shows that major life changes – starting a new school, moving, family problems, relationship break-ups or the death of a loved one, may trigger eating disorders or make mild symptoms worse.

Why do you need treatment for eating disorders?

Eating Disorders are complex and typically include co-occurring disorders and issues. They affect the whole person and family. Although it can happen, it is very difficult to recovery on your own. A team of professionals is recommended given the biological, psychological, social, and nutritional issues that are present.

They affect the whole person and family. Although it can happen, it is very difficult to recovery on your own. A team of professionals is recommended given the biological, psychological, social, and nutritional issues that are present.

I’m worried someone I care about has anorexia. How can I tell if it’s just normal weight loss or if they need help?

Anorexia has behavioral and emotional components, including dramatic weight loss, trying to hide weight loss, preoccupation with weight, food, calories or dieting, refusing to eat certain foods or whole categories of food, maintaining a rigid exercise routine and developing rituals around food (such as insisting on eating foods in a certain order).

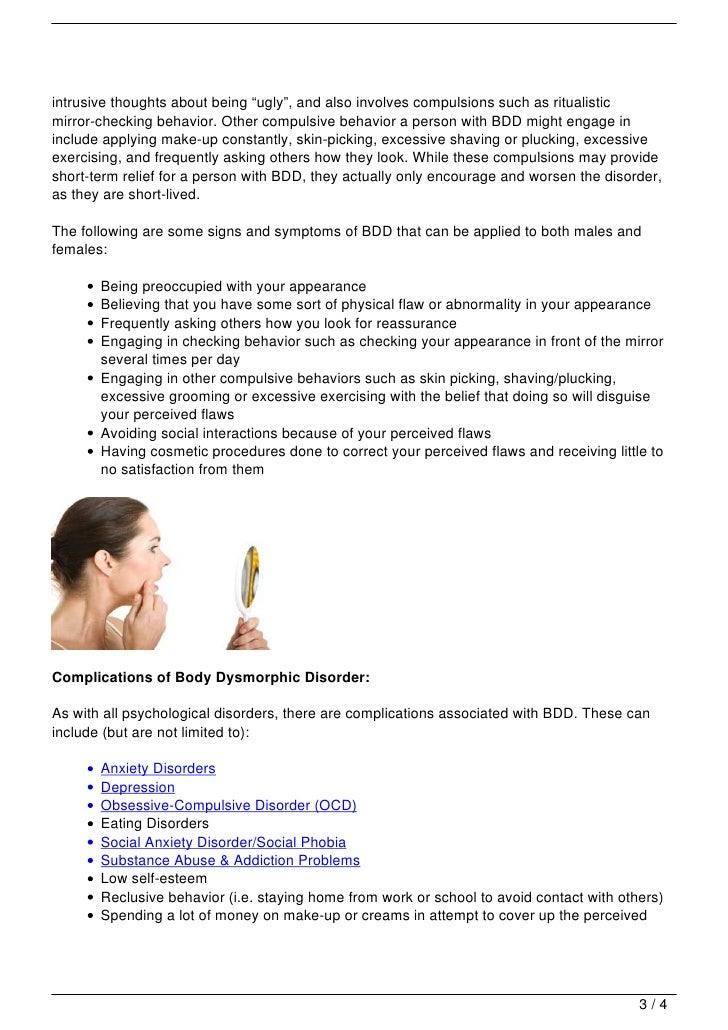

Anorexia can also impact how people interact with their friends and loved ones. Irritability, depression, not wanting to eat in public, frequently looking in the mirror to look for perceived flaws and social withdrawal or loss of interest in activities once enjoyed could mean someone is suffering with anorexia.

My teenager is acting very secretive and withdrawn, and seems to be spending a lot of time in the bathroom with the water running. Could it be bulimia?

People with bulimia are typically found out when their loved ones detect self-induced vomiting because of sights, sounds or smells. Clues that a person may have bulimia include frequently going to the bathroom during meals or right after eating, flushing the toilet multiple times, running tap water or the shower while in the bathroom to disguise the sound of vomiting, taking more than one shower a day to provide an opportunity to purge, using a lot of mouthwash or breath mints to hide the smell, and a raspy or scratchy voice.

Although harder for friends and family to notice, medical professionals may also spot damaged teeth and gums, swollen salivary glands in the cheeks, and sores in the throat and mouth. People with bulimia may also misuse laxatives, which they mistakenly believe will flush calories from the body, or ipecac syrup to induce vomiting. (Ipecac is intended to be taken after suspected poisoning.)

(Ipecac is intended to be taken after suspected poisoning.)

There are times that I feel out of control around food, and terribly guilty after I’ve overeaten. Do I have binge eating disorder?

When people binge eat, they typically eat large amounts of food, rapidly, and continue even when full. They may eat alone, hoard food, or hide boxes and wrappers. After a binge, people often feel disgusted or ashamed by their behavior. People who binge eat may go on and off diets and go up and down in weight. Low self-esteem, social withdrawal and depression may also accompany binge eating disorder.

Can people have more than one eating disorder at the same time?

Eating disorder symptoms don’t always fit neatly into one category. For example, some people with anorexia also purge. Some people with bulimia may also exercise excessively to control their weight. Others may alternate between anorexia and bulimia. People with bulimia may also binge eat.

The important thing to understand is that the behaviors associated with eating disorders are often a manifestation of emotional issues. If someone is struggling with food, eating, body image, self-esteem, excessive exercise or other aspects of their mental health, they should receive help.

If someone is struggling with food, eating, body image, self-esteem, excessive exercise or other aspects of their mental health, they should receive help.

At Rosewood, I discovered who I really am and what I am capable of

Read more testimonials

Can Eating Disorders be Cured?

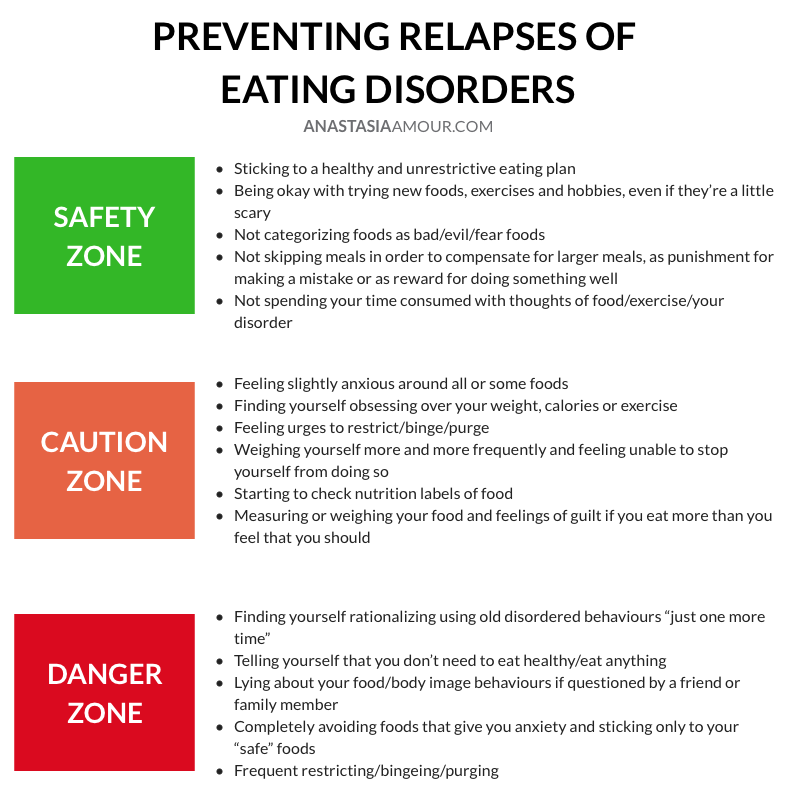

Eating disorders can be cured, in that people can fully recover and their eating disorder behaviors may never reoccur. Those individuals have not only returned to balanced eating and a healthy relationship with food, but they have also developed a positive body image, learned effective coping skills to deal with stress or anxiety, and moved past the feelings, experiences and fears that contributed to the problem.

In some people, however, even if they are no longer actively engaging in eating disorders behaviors, continue to have eating disorder thoughts creep in. In recovery, they have to pay close attention to their physical health and their mental health to avoid slipping back into dangerous habits. To help these individuals stay on track, ongoing therapy, connection with their therapeutic team and community-based support are crucial. Rosewood has a strong alumni program made of up people from all over the United States who get together to provide that companionship and encouragement to one other.

In recovery, they have to pay close attention to their physical health and their mental health to avoid slipping back into dangerous habits. To help these individuals stay on track, ongoing therapy, connection with their therapeutic team and community-based support are crucial. Rosewood has a strong alumni program made of up people from all over the United States who get together to provide that companionship and encouragement to one other.

Yes but there are significant neurobiological, biological and genetic influences.

Can You Tell by Looking at Someone That They Have an Eating Disorder?

Often you can’t. People with eating disorders may be a normal weight or look healthy. Their appearance may not match the anxiety around food and eating they feel inside. People with eating disorders also often have a distorted body image. To an outsider, they look perfectly fine. Yet inside the person is preoccupied with their physical appearance, to the point that it is crowding out other thoughts.

Who is Vulnerable to Eating Disorders?

People of any age, including boys, girls, men and women. The media tends to focus on adolescent girls and young women with eating disorders. As a group, they do tend to have higher rates of eating disorders. But about 15% of our patients at Rosewood are men and boys, a number that has steadily risen.

Members of the LGBTQ community are also vulnerable to eating disorders. Struggles with coming out, gender expression and school or workplace bullying are thought to be contributing factors. These experiences can lead anxiety, depression, low self-esteem and trauma-related issues, which are known to be associated with the development of eating disorders.

How Can I talk to Someone If I Suspect They Have an Eating Disorder?

Being confronted about an eating disorder can be difficult for someone to hear.Choose a time when you can speak privately, when you’re calm and when your family member or friend isn’t overly stressed. Explain your concern and give examples of specific situations and behaviors that worry you. Don’t take it personally if the person you care about lies about their behavior or becomes defensive. This is a very common reaction. Being ‘found out’ may feel threatening to them. Be patient, and supportive, and let them know help is available.

Explain your concern and give examples of specific situations and behaviors that worry you. Don’t take it personally if the person you care about lies about their behavior or becomes defensive. This is a very common reaction. Being ‘found out’ may feel threatening to them. Be patient, and supportive, and let them know help is available.

We are here to help you.

Call (800) 845-2211

Where can you find eating disorder treatment centers?

All over the country – particularly in metropolitan areas.

When do you need treatment for eating disorders?

When eating disorder symptoms cause physical, mental, emotional and/or social dysfunction in your life and /or interfere with your relationship with food, self, and others.

What are eating disorder treatment centers?

Facilities that have a multidisciplinary team and specialize in the treatment of eating disorders and co-occurring disorders. They include various levels of care including inpatient, residential, partial hospitalization, intensive outpatient, and outpatient.

How many eating disorder treatment centers are there for Rosewood?

There are 4 eating disorder treatment centers for Rosewood.

How do you treat patients related to eating disorders?

Integrative care with evidenced-based treatment including dialectical behavior therapy, cognitive behavior therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, as well as trauma informed care and treatment, including EMDR. We also treat co-occurring substance abuse disorders. Treatment includes 12-step model, group work and the AddictBrain curriculum. We include nutritional therapy and experientials, including meal support and monitoring. We have a medical team of physicians and psychiatrics caring for our patients. We also do group therapy including therapeutic process groups, body image therapy, aftercare and relapse prevention groups, art therapy, equine, and recreational therapy.

Do you also give medicines to treat eating disorders?

Yes when appropriate for co-occurring disorders. There are no specific medications designated to treat eating disorders.

There are no specific medications designated to treat eating disorders.

Can Eating Disorders Just Go Away Without Treatment?

They can, but not often, and it’s a dangerous and potentially deadly chance to take. A lot of people don’t want to admit that they have an eating disorder, or that their child has an eating disorder. So they put off treatment, thinking they can get a handle on it on their own or it’s just a phase.

Research shows that the earlier eating disorders are diagnosed and treated, the more likely someone will recover completely. The longer an eating disorder is allowed to progress, the more likely the individual will suffer long-term consequences to the bones, muscles, heart, kidneys, stomach, teeth, skin, hair and brain.

People die of eating disorders complications every day. If someone you love is struggling, they deserve help from qualified medical professionals and eating disorders experts who can help them heal, physically and mentally.

If you have more questions about eating disorders, contact Rosewood at 844-335-0871. We can provide information about eating disorders, advice on next steps and a confidential consultation.

We can provide information about eating disorders, advice on next steps and a confidential consultation.

Rosewood Eating Disorder

Treatment Centers & Locations

Get help now

(800) 845-2211

Insurance TypeEmployer ProvidedGovernment Provided (Medicare/Medicaid)Self ProvidedNoneRelationship to Patient--None--BrotherClinical ProfessionalDaughterFatherFriendGirl/boyfriendGrandparentHusbandMotherOtherPartnerSelfSisterSonSponsorWife

In-Network With Most Insurance Plans

Blue Cross Blue Shield

Beacon Health Options

First Health Network

Magellan

MultiPlan

Kaiser

United Healthcare

Accreditations & Memberships

Joint Commission Gold Seal of Approval

Residential Eating Disorders Consortium

National Eating Disorders Association

Eating Disorders Coalition

The Alliance for Eating Disorder Awareness

International Association of Eating Disorders Professionals

Follow Us

Facebook Twitter Youtube Linkedin Instagram

Facebook Twitter Linkedin Instagram

© Rosewood Centers for Eating Disorders

© 2020 Monte Nido & Affiliates

All rights reserved

We save lives while providing the opportunity for people to realize their healthy selves.

Parents' Frequently Asked Questions | Making an appointment at TsIRPP in Moscow

- Can we limit ourselves to taking drugs and visiting a psychiatrist, without visiting other doctors?

- You can, but it's inefficient! Only taking drugs can not guarantee not to get into this situation again. Psychotherapy teaches you to experience your unpleasant emotions without suffering. It is impossible to help your child without comprehensive treatment and the cooperation of all. There is a "gold standard" of work - taking drugs, working with a psychiatrist, psychologist, psychotherapist, nutrition consultant.

- How long do the drugs need to be taken? How strong drugs will my child need to take? How dangerous are these drugs?

- All drugs are prescribed based on clear criteria. We justify each drug. This rationale is based on scientific research. Each prescribed drug shows its effectiveness. The drug is selected for each condition individually.

The time of taking the drug is calculated individually, based on the condition of your child. But there are some common points. In the treatment of RPP, drugs of 3 groups are prescribed: - antidepressants (taken from 6 months to 1.5 years. On average, from 7 to 10 months continuously.) - mood stabilizers (taken most often for 1 year). - antipsychotics (used depending on the condition of your child). There are no general recommendations. It is very important to take the drugs exactly according to the scheme prescribed by the doctor. You cannot stop taking medications on your own. Abrupt cancellation can lead to a worsening of the condition. Drugs by themselves do not solve the problem completely, but they provide an opportunity to recover. Drugs cannot make life better or worse. It's just supportive therapy. It can be compared with gypsum, which is applied at a fracture. It does not solve the problem, but it makes it possible to recover from the existing problem. If the plaster is removed prematurely, then a repeated fracture may follow.

The time of taking the drug is calculated individually, based on the condition of your child. But there are some common points. In the treatment of RPP, drugs of 3 groups are prescribed: - antidepressants (taken from 6 months to 1.5 years. On average, from 7 to 10 months continuously.) - mood stabilizers (taken most often for 1 year). - antipsychotics (used depending on the condition of your child). There are no general recommendations. It is very important to take the drugs exactly according to the scheme prescribed by the doctor. You cannot stop taking medications on your own. Abrupt cancellation can lead to a worsening of the condition. Drugs by themselves do not solve the problem completely, but they provide an opportunity to recover. Drugs cannot make life better or worse. It's just supportive therapy. It can be compared with gypsum, which is applied at a fracture. It does not solve the problem, but it makes it possible to recover from the existing problem. If the plaster is removed prematurely, then a repeated fracture may follow. And in the case of eating disorders, we are talking about a biochemical breakdown of the body.

And in the case of eating disorders, we are talking about a biochemical breakdown of the body.

- All drugs are prescribed based on clear criteria. We justify each drug. This rationale is based on scientific research. Each prescribed drug shows its effectiveness. The drug is selected for each condition individually.

- Will my child be cured?

- Yes, of course. With a comprehensive, correct approach, anorexia nervosa is a disease that can be cured.

- How long does it take to take psychotropic medications?

- Everything is individual. With a stable remission, the drugs are gradually canceled. But the timing of achieving remission is very individual.

- Is it possible to do without psychotropic pharmacology? Will it be enough just to work out with a psychologist for everything to go away?

- No. It is forbidden. Because eating disorder is an emotional disorder that requires, among other things, medication correction.

- Is RPP treated?

- Yes, it is being treated. It is possible to achieve long-term remissions while the patient goes through all stages of treatment and is actively involved in the process himself.

Also important is the involvement of parents in the process, who must attend groups for parents and have an idea of how to behave further, what to do in various situations, and develop a certain tactic of behavior for themselves.

Also important is the involvement of parents in the process, who must attend groups for parents and have an idea of how to behave further, what to do in various situations, and develop a certain tactic of behavior for themselves.

- Yes, it is being treated. It is possible to achieve long-term remissions while the patient goes through all stages of treatment and is actively involved in the process himself.

- How long does the treatment take?

- Everything is very individual. Treatment consists of several stages - recovery, rehabilitation, and so on. Generally speaking, the average time is 2-3 months.

- How did my child get sick?

- RPP is a multifactorial disease. The start of the disease is given by the coincidence of several factors - genetic predisposition, increased emotional sensitivity, a crisis in life, fixation on certain goals.

- Is lifelong maintenance medication mandatory?

- No. In most cases, we are talking about taking medications after discharge from 6 months to 1.5 years.

- What is the duration of hospitalization?

- On average, hospitalization lasts 2 to 5 months.

For each individual patient, the timing is individual. Deviations are possible both up and down.

For each individual patient, the timing is individual. Deviations are possible both up and down.

- On average, hospitalization lasts 2 to 5 months.

- What are the reasons for what happened to my child?

- Absolutely no one is to blame for the sick child! To date, genes are precisely known, the presence of which significantly increases the risk of developing ED, without these genes, the disease will not happen! Genes are concerned with three things: high emotional sensitivity, fine-grained thinking, and disturbances in the satiety-hunger regulatory system.

- Who is to blame for our child getting sick?

-

Parents often believe that finding the cause of an eating disorder is enough to fix the problem right away. In fact, the cause is not so important for the course of treatment, and it is quite possible to look for it later, when your child's health is put in order. In addition, the search may not be so fast, because there is no single cause of eating disorders. All possible causes are divided into three large groups.

The first group is constitutional: researchers have identified genes that increase the risk of developing this disease. This also includes the increased sensitivity with which a person is born and lives. The second group of reasons refers to family factors: ways of raising a child, building relationships in the family, the presence of a complete or incomplete family, and so on. One way or another, these are the events that have already happened, and they cannot be changed, besides, behavior patterns are formed, mainly, at the age of 3 years. The third group of reasons is the social environment: mocking classmates, dieting girlfriends, fashion magazines broadcasting thinness standards, and so on. Is it possible to influence all this complex of causes? Of course no.

The first group is constitutional: researchers have identified genes that increase the risk of developing this disease. This also includes the increased sensitivity with which a person is born and lives. The second group of reasons refers to family factors: ways of raising a child, building relationships in the family, the presence of a complete or incomplete family, and so on. One way or another, these are the events that have already happened, and they cannot be changed, besides, behavior patterns are formed, mainly, at the age of 3 years. The third group of reasons is the social environment: mocking classmates, dieting girlfriends, fashion magazines broadcasting thinness standards, and so on. Is it possible to influence all this complex of causes? Of course no.

-

- Is my daughter crazy? Is it schizophrenia?

-

No medical condition rules out schizophrenia, but it is not schizophrenia in and of itself. Within the framework of schizophrenia, eating disorders can be identified, but there are other fairly striking symptoms that make it possible to speak of schizophrenia.

You can draw an analogy with tuberculosis: with tuberculosis there is a cough - but this does not mean that every cough is tuberculosis.

You can draw an analogy with tuberculosis: with tuberculosis there is a cough - but this does not mean that every cough is tuberculosis.

-

- Will she get better? Is there any way to get out of this?

-

Your child has a very high chance of being cured. Statistics show that approximately 65% of patients with eating disorders achieve stable remission. Approximately 30% after improvement of the condition have relapses due to serious stressful situations: the loss of a loved one, work, deterioration of physical condition. And only 5% of patients fail to achieve results. It should also be borne in mind that the process of recovering from an eating disorder - just like from alcoholism or drug addiction - always requires "keeping a finger on the pulse" and controlling at what stage (good, not very good or bad) a person is. In other words, the main thing in this process is to achieve a good physical and psychological state and try to keep it.

-

- What should I do to get her to stop behaving like that / to make her gain weight?

-

There is no direct connection between your actions, no matter how wonderful, and your daughter's illness.

We can give advice on how to help her, but there is nothing you can do to make her start or stop eating.

We can give advice on how to help her, but there is nothing you can do to make her start or stop eating.

-

- Did it all happen because she's selfish? Why can't she act right? She doesn't love me, doesn't love her family?

-

Your daughter is sick. All this she does not out of harm or bad behavior, it is due to her constant extreme fear and obsessive thoughts. Her "behavior" is associated with deep emotional experiences, in which she also experiences great guilt for what she is doing. And when you ask, "Is it because you don't love me?" Her guilt is compounded many times over. Or say to yourself, “It’s my fault, I didn’t raise it correctly!”, Your guilt causes additional anxiety, anxiety and anger. It is very important to understand that guilt is the worst adviser for you and your daughter right now. And the best advice we can give to parents is “Get rid of guilt right now!” It's nobody's fault that your child is sick!

-

* — required fields

By submitting an application, you agree to the terms

of the privacy policy

We use cookies, set by our experts and third parties, to analyze the activities on our website, which allows us to improve user experience and service.

By continuing to browse our site, you accept the terms of its use. For more information, see our Cookie Policy.

11 facts about eating disorders - a list for understanding the disease

Note. Ed.: If you have an eating disorder, the following text may be a potential trigger.

I compiled this list to let others know about my path to recovery, and I hope it helps them understand a little more about eating disorders.

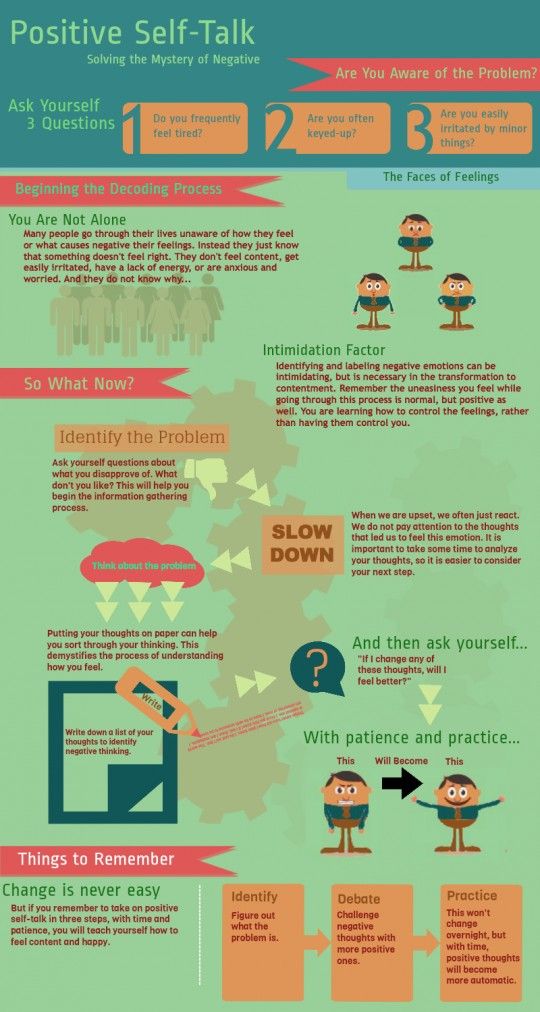

Every person who has struggled with an eating disorder knows how much guilt and shame accompanied him because of the diagnosis. Trying to cope not only with the disease itself, but also with inappropriate comments and misconceptions of others about eating disorders, makes this burden unbearable.

1. It's not always about food.

Yes, it's called an "eating disorder", how could it not be about food? Simply put, food is a pawn in an endless game of the mind, addiction. By addiction, I mean that a person struggling with an eating disorder may be addicted to food in some way. Whether it's an addiction to food, thoughts about food, or self-punishment with food. The causes of RPP are much deeper. And in fact, they have much less to do with food than you might imagine.

Whether it's an addiction to food, thoughts about food, or self-punishment with food. The causes of RPP are much deeper. And in fact, they have much less to do with food than you might imagine.

2.

Not all people who struggle with eating disorders look like they are sick.In fact, people who struggle with eating disorders may feel unworthy of help and do not seek support because they are "not sick enough." What does “sick enough” mean for a person with an eating disorder? He may not be "skinny enough". I can say from my personal experience that I had to put in much more effort to deal with an eating disorder at a normal weight than when I was seriously underweight. I can also note that at least 9out of 10 people I've met who struggle with eating disorders look physically healthy.

3.

An eating disorder is not just anorexia. This common misconception is reinforced by misinformation and lack of awareness about eating disorders, as well as thinness propaganda in the media. There are many types of eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, compulsive overeating, orthorexia, selective eating, and others. And, for the record, no eating disorder is superior to another—they can all kill.

There are many types of eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, compulsive overeating, orthorexia, selective eating, and others. And, for the record, no eating disorder is superior to another—they can all kill.

4.

When recovering from one eating disorder, you can fall into the trap of another. This is something no one warned me about. No one, not a single soul told me that this was possible. And for so long, I felt alone because everyone around me had the same mindset and thoughts about recovery. They thought that since my weight had come back and I had, for the most part, recovered from my restrictive eating disorder, I was fine. They had no idea that my obsession with exercise had reached its peak, and now I was struggling not only with making myself eat, but also with guilt for not being able to compensate for it. It wasn't until I heard someone else talking about it that I realized I wasn't alone. So if you are in a similar situation right now, know that you are not alone.

5.

An eating disorder does not appear immediately, so it will not disappear immediately.Imagine how long it can take a person to, for example, learn how to drive a car confidently and safely? Or, let's say you didn't drive a car for a whole month, and then you got behind the wheel and ... Have you forgotten all the acquired driving skills? Probably not. It will also take a long time for someone struggling with an eating disorder to leave the habitual mindset of a person with eating disorders and recover with the support of qualified professionals.

6.

I want to get well… But I am very tired. I've said this a million times and the most common responses are: "You just need to pull yourself together" or "If you really wanted to get well, you would have done it already." Well, and my favorite: "You just love the attention you get because of your illness." But no, it's not easy. You can't set a time frame for recovery, and no, I don't like the attention I'm getting because of my illness. Recovery is all-day work plus overtime. And the only immediate reward for all the hard work I get through is a good night's sleep because I'm exhausted both physically and mentally. Imagine running from a crocodile through a swamp with ten bricks on each shoulder. That's what recovery is for me.

Recovery is all-day work plus overtime. And the only immediate reward for all the hard work I get through is a good night's sleep because I'm exhausted both physically and mentally. Imagine running from a crocodile through a swamp with ten bricks on each shoulder. That's what recovery is for me.

7.

Treatment for an eating disorder often exacerbates symptoms of other mental illnesses. For example, once I started eating regularly and no longer used compensatory behaviors to regulate my emotions and punish myself, my depression worsened. At first, I blamed depression on my weight gain and changes in my body. But in reality, I could no longer numb the symptoms of depression with the help of an eating disorder. When you suffer from an eating disorder, you are completely absorbed in it, all your efforts are focused on worrying about weight and figure. Don't assume that a person who is recovering from an eating disorder and "suddenly depressed" is just jumping from one diagnosis to another. Because I doubt I've ever met a person who struggles with an eating disorder and doesn't have an underlying mental illness.

Because I doubt I've ever met a person who struggles with an eating disorder and doesn't have an underlying mental illness.

8.

Recovery is the hardest thing I have ever had to do. I have no words to describe how difficult it is to recover. But I will try. Recovery doesn't just mean sticking to a specific eating plan and putting on a few pounds. Think of the one thing in the world that scares you the most, and then imagine having to deal with it several times a day for the rest of your days. The mere thought of letting go of an eating disorder that has been with me throughout my life is amazing. But what's even worse is the realization that living with an eating disorder is like signing your own death warrant. So you choose to get well and fight with yourself every time you eat. And then it starts to overwhelm you so much that surrendering to the disease seems like the only way out. You are so afraid of your own mind that death no longer seems such a frightening prospect. It is a constant balancing act between life and death. And this is not an exaggeration. Recovery is the hardest thing I have ever had to do.

It is a constant balancing act between life and death. And this is not an exaggeration. Recovery is the hardest thing I have ever had to do.

9.

You can't force someone to get well.Yes, you think you can convince a person with an eating disorder to choose recovery, but that's just their way. And the decision is up to him. And in the process of recovery, it is very important that a person knows that his opinion is respected and valued. You can try to accuse the person suffering from eating disorders of selfishness. But keep in mind that this will do more harm than good.

10.

Weight gain does not mean recovery.Restoring and maintaining weight is a huge step forward, but from my own experience, this does not mean recovery. It's just restoring the lost weight. You can't say, "I've gained weight, so now I'm cured."

11.

Thinking and talking about suicide is not attention-grabbing. The emotions associated with living with an eating disorder, let alone dealing with it, are overwhelming.