Environmental causes of bipolar

Environmental factors, life events, and trauma in the course of bipolar disorder

1. Ketter TA. Diagnostic features, prevalence, and impact of bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010; 71: e14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J et al. Lifetime and 12‐month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007; 64: 543–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Bauer M, Pfennig A. Epidemiology of bipolar disorders. Epilepsia 2005; 46 (Suppl. 4): 8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Merikangas KR, Jin R, He J‐P et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011; 68: 241–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Latalova K, Prasko J, Diveky T, Kamaradova D, Velartova H. Cognitive dysfunction, dissociation and quality of life in bipolar affective disorders in remission. Psychiatr. Danub. 2010; 22: 528–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Phillips ML, Kupfer DJ. Bipolar disorder diagnosis: Challenges and future directions. Lancet 2013; 381: 1663–1671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Hosang GM, Korszun A, Jones L et al. Adverse life event reporting and worst illness episodes in unipolar and bipolar affective disorders: Measuring environmental risk for genetic research. Psychol. Med. 2010; 40: 1829–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Anand A, Koller DL, Lawson WB, Gershon ES, Nurnberger JI. Genetic and childhood trauma interaction effect on age of onset in bipolar disorder: An exploratory analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2015; 179: 1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Mondimore FM. Kraepelin and manic‐depressive insanity: An historical perspective. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2005; 17: 49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Zivanovic O, Nedic A. Kraepelin's concept of manic‐depressive insanity: One hundred years later. J. Affect. Disord. 2012; 137: 15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J. Affect. Disord. 2012; 137: 15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Bender RE, Alloy LB. Life stress and kindling in bipolar disorder: Review of the evidence and integration with emerging biopsychosocial theories. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011; 31: 383–398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Post RM. Kindling and sensitization as models for affective episode recurrence, cyclicity, and tolerance phenomena. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2007; 31: 858–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Ferreira MAR, O'Donovan MC, Meng YA et al. Collaborative genome‐wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nat. Genet. 2008; 40: 1056–1058. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Fiorentino A, O'Brien NL, Locke DP et al. Analysis of ANK3 and CACNA1C variants identified in bipolar disorder whole genome sequence data. Bipolar Disord. 2014; 16: 583–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Craddock N, Sklar P. Genetics of bipolar disorder. Lancet 2013; 381: 1654–1662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Genetics of bipolar disorder. Lancet 2013; 381: 1654–1662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Cross‐Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: A genome‐wide analysis. Lancet 2013; 381: 1371–1379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Forstner AJ, Hofmann A, Maaser A et al. Genome‐wide analysis implicates microRNAs and their target genes in the development of bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2015; 5: e678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O'Donovan M. Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: The emerging picture and its implications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012; 13: 537–551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Baum AE, Akula N, Cabanero M et al. A genome‐wide association study implicates diacylglycerol kinase eta (DGKH) and several other genes in the etiology of bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2008; 13: 197–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry 2008; 13: 197–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Sklar P, Ripke S, Scott LJ et al. Large‐scale genome‐wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat. Genet. 2011; 43: 977–983. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Pang D, Syed S, Fine P, Jones PB. No association between prenatal viral infection and depression in later life–a long‐term cohort study of 6152 subjects. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009; 54: 565–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Mcgrath JJ et al. Neonatal antibodies to infectious agents and risk of bipolar disorder: A population‐based case–control study. Bipolar Disord. 2011; 13: 624–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Parboosing R, Bao Y, Shen L, Schaefer CA, Brown AS. Gestational influenza and bipolar disorder in adult offspring. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70: 677–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Canetta SE, Bao Y, Co MDT et al. Serological documentation of maternal influenza exposure and bipolar disorder in adult offspring. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014; 171: 557–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Serological documentation of maternal influenza exposure and bipolar disorder in adult offspring. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014; 171: 557–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J. Affect. Disord. 2011; 130: 220–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Tedla Y, Shibre T, Ali O et al. Serum antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii and Herpesvidae family viruses in individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A case–control study. Ethiop. Med. J. 2011; 49: 211–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Pearce BD, Kruszon‐Moran D, Jones JL. The relationship between Toxoplasma gondii infection and mood disorders in the third National Health and Nutrition Survey. Biol. Psychiatry 2012; 72: 290–295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Hamdani N, Daban‐Huard C, Lajnef M et al. Relationship between Toxoplasma gondii infection and bipolar disorder in a French sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2013; 148: 444–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Relationship between Toxoplasma gondii infection and bipolar disorder in a French sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2013; 148: 444–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Ekblad M, Gissler M, Lehtonen L, Korkeila J. Prenatal smoking exposure and the risk of psychiatric morbidity into young adulthood. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010; 67: 841–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Talati A, Bao Y, Kaufman J, Shen L, Schaefer CA, Brown AS. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and bipolar disorder in offspring. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013; 170: 1178–1185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Chudal R, Brown AS, Gissler M, Suominen A, Sourander A. Is maternal smoking during pregnancy associated with bipolar disorder in offspring? J. Affect. Disord. 2015; 171: 132–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Bain M, Juszczak E, McInneny K, Kendell RE. Obstetric complications and affective psychoses. Two case–control studies based on structured obstetric records. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000; 176: 523–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br. J. Psychiatry 2000; 176: 523–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Øgendahl BK, Agerbo E, Byrne M, Licht RW, Eaton WW, Mortensen PB. Indicators of fetal growth and bipolar disorder: A Danish national register‐based study. Psychol. Med. 2006; 36: 1219–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Nosarti C, Reichenberg A, Murray RM et al. Preterm birth and psychiatric disorders in young adult life. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012; 69: 610–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Chudal R, Sourander A, Polo‐Kantola P et al. Perinatal factors and the risk of bipolar disorder in Finland. J. Affect. Disord. 2014; 155: 75–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Volpe FM, da Silva EM, dos Santos TN, de Freitas DEG. Further evidence of seasonality of mania in the tropics. J. Affect. Disord. 2010; 124: 178–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Dominiak M, Swiecicki L, Rybakowski J. Psychiatric hospitalizations for affective disorders in Warsaw, Poland: Effect of season and intensity of sunlight. Psychiatry Res. 2015; 229: 287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry Res. 2015; 229: 287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Geoffroy PA, Bellivier F, Scott J, Etain B. Seasonality and bipolar disorder: A systematic review, from admission rates to seasonality of symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2014; 168: 210–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Young JW, Dulcis D. Investigating the mechanism(s) underlying switching between states in bipolar disorder. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015; 759: 151–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Rajkumar RP, Sarkar S. Seasonality of admissions for mania: Results from a general hospital psychiatric unit in Pondicherry, India. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015; 17. doi: 10.4088/PCC.15m01780. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Hochman E, Valevski A, Onn R, Weizman A, Krivoy A. Seasonal pattern of manic episode admissions among bipolar I disorder patients is associated with male gender and presence of psychotic features. J. Affect. Disord. 2016; 190: 123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Kennedy BL, Dhaliwal N, Pedley L, Sahner C, Greenberg R, Manshadi MS. Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder in subjects with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J. Ky. Med. Assoc. 2002; 100: 395–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Garno JL, Goldberg JF, Ramirez PM, Ritzler BA. Impact of childhood abuse on the clinical course of bipolar disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005; 186: 121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Kauer‐Sant'Anna M, Tramontina J, Andreazza AC et al. Traumatic life events in bipolar disorder: Impact on BDNF levels and psychopathology. Bipolar Disord. 2007; 9 (Suppl. 1): 128–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Quarantini LC, Miranda‐Scippa A, Nery‐Fernandes F et al. The impact of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder on bipolar disorder patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2010; 123: 71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Fisher H, Hosang G. Childhood maltreatment and bipolar disorder : A critical review of the evidence. Mind Brain 2010; 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

Mind Brain 2010; 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

47. Daruy‐Filho L, Brietzke E, Lafer B, Grassi‐Oliveira R. Childhood maltreatment and clinical outcomes of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2011; 124: 427–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Miller S, Hallmayer J, Wang PW, Hill SJ, Johnson SL, Ketter TA. Brain‐derived neurotrophic factor val66met genotype and early life stress effects upon bipolar course. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013; 47: 252–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Aas M, Haukvik UK, Djurovic S et al. Interplay between childhood trauma and BDNF val66met variants on blood BDNF mRNA levels and on hippocampus subfields volumes in schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014; 59: 14–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Girshkin L, Matheson SL, Shepherd AM, Green MJ. Morning cortisol levels in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A meta‐analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014; 49: 187–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Benedetti F, Riccaboni R, Poletti S et al. The serotonin transporter genotype modulates the relationship between early stress and adult suicidality in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2014; 16: 857–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Benedetti F, Riccaboni R, Poletti S et al. The serotonin transporter genotype modulates the relationship between early stress and adult suicidality in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2014; 16: 857–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Sala R, Goldstein BI, Wang S, Blanco C. Childhood maltreatment and the course of bipolar disorders among adults: Epidemiologic evidence of dose–response effects. J. Affect. Disord. 2014; 165: 74–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Baumeister D, Akhtar R, Ciufolini S, Pariante CM, Mondelli V. Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: A meta‐analysis of peripheral C‐reactive protein, interleukin‐6 and tumour necrosis factor‐α. Mol. Psychiatry 2016; 21: 642–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Etain B, Lajnef M, Henrion A et al. Interaction between SLC6A4 promoter variants and childhood trauma on the age at onset of bipolar disorders. Sci. Rep. 2015; 5: 16301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Oliveira J, Etain B, Lajnef M et al. Combined effect of TLR2 gene polymorphism and early life stress on the age at onset of bipolar disorders. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0119702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119702. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Oliveira J, Etain B, Lajnef M et al. Combined effect of TLR2 gene polymorphism and early life stress on the age at onset of bipolar disorders. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0119702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119702. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Benedetti F, Riccaboni R, Dallaspezia S, Locatelli C, Smeraldi E, Colombo C. Effects of CLOCK gene variants and early stress on hopelessness and suicide in bipolar depression. Chronobiol. Int. 2015; 32: 1156–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Mert DG, Kelleci M, Mizrak A, Semiz M, Demir MO. Factors associated with suicide attempts in patients with bipolar disorder type I. Psychiatr. Danub. 2015; 27: 236–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Aas M, Henry C, Andreassen OA, Bellivier F, Melle I, Etain B. The role of childhood trauma in bipolar disorders. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2016; 4: 2. doi: 10.1186/s40345-015-0042-0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Ellicott A, Hammen C, Gitlin M, Brown G, Jamison K. Life events and the course of bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990; 147: 1194–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Life events and the course of bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990; 147: 1194–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Malkoff‐Schwartz S, Frank E, Anderson B et al. Stressful life events and social rhythm disruption in the onset of manic and depressive bipolar episodes: A preliminary investigation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1998; 55: 702–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Hlastala SA, Frank E, Kowalski J et al. Stressful life events, bipolar disorder, and the “kindling model”. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2000; 109: 777–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Paykel ES. Life events and affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2003; 108: 61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Christensen EM, Gjerris A, Larsen JK et al. Life events and onset of a new phase in bipolar affective disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2003; 5: 356–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Hillegers MHJ, Burger H, Wals M et al. Impact of stressful life events, familial loading and their interaction on the onset of mood disorders: Study in a high‐risk cohort of adolescent offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004; 185: 97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br. J. Psychiatry 2004; 185: 97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Cohen AN, Hammen C, Henry RM, Daley SE. Effects of stress and social support on recurrence in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2004; 82: 143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Johnson SL. Life events in bipolar disorder: Towards more specific models. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005; 25: 1008–1027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Kessing LV, Andersen PK. Predictive effects of previous episodes on the risk of recurrence in depressive and bipolar disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2005; 7: 413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Urosevic S, Walshaw PD, Nusslock R, Neeren AM. The psychosocial context of bipolar disorder: Environmental, cognitive, and developmental risk factors. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005; 25: 1043–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Kim EY, Miklowitz DJ, Biuckians A, Mullen K. Life stress and the course of early‐onset bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2007; 99: 37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Disord. 2007; 99: 37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Johnson SL, Cuellar AK, Ruggero C et al. Life events as predictors of mania and depression in bipolar I disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2008; 117: 268–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Gruber J, Miklowitz DJ, Harvey AG et al. Sleep matters: Sleep functioning and course of illness in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2011; 134: 416–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Boland EM, Bender RE, Alloy LB, Conner BT, Labelle DR, Abramson LY. Life events and social rhythms in bipolar spectrum disorders: An examination of social rhythm sensitivity. J. Affect. Disord. 2012; 139: 264–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Hosang GM, Korszun A, Jones L, Jones I, McGuffin P, Farmer AE. Life‐event specificity: Bipolar disorder compared with unipolar depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012; 201: 458–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. De Dios C, González‐Pinto A, Montes JM et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorders in Spain (PREBIS study data). J. Affect. Disord. 2012; 141: 406–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

De Dios C, González‐Pinto A, Montes JM et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorders in Spain (PREBIS study data). J. Affect. Disord. 2012; 141: 406–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Gershon A, Johnson SL, Miller I. Chronic stressors and trauma: Prospective influences on the course of bipolar disorder. Psychol. Med. 2013; 43: 2583–2592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Koenders MA, Giltay EJ, Spijker AT, Hoencamp E, Spinhoven P, Elzinga BM. Stressful life events in bipolar I and II disorder: Cause or consequence of mood symptoms? J. Affect. Disord. 2014; 161: 55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Simhandl C, Radua J, König B, Amann BL. The prevalence and effect of life events in 222 bipolar I and II patients: A prospective, naturalistic 4 year follow‐up study. J. Affect. Disord. 2014; 170: 166–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Kemner SM, van Haren N, Bootsman F et al. The influence of life events on first and recurrent admissions in bipolar disorder. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2015; 3: 6. doi: 10.1186/s40345-015-0022-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2015; 3: 6. doi: 10.1186/s40345-015-0022-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

79. Kemner SM, Mesman E, Nolen WA, Eijckemans MJC, Hillegers MHJ. The role of life events and psychological factors in the onset of first and recurrent mood episodes in bipolar offspring: Results from the Dutch Bipolar Offspring Study. Psychol. Med. 2015; 45: 2571–2581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Maciukiewicz M, Pawlak J, Kapelski P et al. Can psychological, social and demographical factors predict clinical characteristics symptomatology of bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia? Psychiatr. Q. 2016; 87: 501–513. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Johnson SL, Winett CA, Meyer B, Greenhouse WJ, Miller I. Social support and the course of bipolar disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1999; 108: 558–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Johnson SL, Meyer B, Winett C, Small J. Social support and self‐esteem predict changes in bipolar depression but not mania. J. Affect. Disord. 2000; 58: 79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J. Affect. Disord. 2000; 58: 79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Johnson SL, Sandrow D, Meyer B et al. Increases in manic symptoms after life events involving goal attainment. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2000; 109: 721–727. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Johnson L, Lundström O, Aberg‐Wistedt A, Mathé AA. Social support in bipolar disorder: Its relevance to remission and relapse. Bipolar Disord. 2003; 5: 129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Miklowitz DJ. The role of the family in the course and treatment of bipolar disorder. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007; 16: 192–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Coville AL, Miklowitz DJ, Taylor DO, Low KG. Correlates of high expressed emotion attitudes among parents of bipolar adolescents. J. Clin. Psychol. 2008; 64: 438–449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Greenberg S, Rosenblum KL, McInnis MG, Muzik M. The role of social relationships in bipolar disorder: A review. Psychiatry Res. 2014; 219: 248–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry Res. 2014; 219: 248–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Ellis AJ, Portnoff LC, Axelson DA, Kowatch RA, Walshaw P, Miklowitz DJ. Parental expressed emotion and suicidal ideation in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2014; 216: 213–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Owen R, Gooding P, Dempsey R, Jones S. A qualitative investigation into the relationships between social factors and suicidal thoughts and acts experienced by people with a bipolar disorder diagnosis. J. Affect. Disord. 2015; 176: 133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Prandovszky E, Gaskell E, Martin H, Dubey JP, Webster JP, McConkey GA. The neurotropic parasite Toxoplasma gondii increases dopamine metabolism. PLoS One 2011: e23866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

91. Yagmur F, Yazar S, Temel HO, Cavusoglu M. May Toxoplasma gondii increase suicide attempt‐preliminary results in Turkish subjects? Forensic Sci. Int. 2010; 199: 15–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Int. 2010; 199: 15–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Hultman CM, Sparén P, Cnattingius S. Perinatal risk factors for infantile autism. Epidemiology 2002; 13: 417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Button TMM, Thapar A, McGuffin P. Relationship between antisocial behaviour, attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder and maternal prenatal smoking. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005; 187: 155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. McClung CA. Circadian rhythms and mood regulation: Insights from pre‐clinical models. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011; 21 (Suppl. 4): 683–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Etain B, Milhiet V, Bellivier F, Leboyer M. Genetics of circadian rhythms and mood spectrum disorders. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011; 21 (Suppl. 4): 676–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Niemegeers P, Dumont GJH, Patteet L, Neels H, Sabbe BGC. Bupropion for the treatment of seasonal affective disorder. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2013; 9: 1229–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Otto MW, Perlman CA, Wernicke R, Reese HE, Bauer MS, Pollack MH. Posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with bipolar disorder: A review of prevalence, correlates, and treatment strategies. Bipolar Disord. 2004; 6: 470–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Etain B, Henry C, Bellivier F, Mathieu F, Leboyer M. Beyond genetics: Childhood affective trauma in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008; 10: 867–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans‐Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, van IJzendoorn MH. The universality of childhood emotional abuse: A meta‐analysis of worldwide prevalence. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2012; 21: 870–890. [Google Scholar]

100. Glaser D. Emotional abuse and neglect (psychological maltreatment): A conceptual framework. Child Abuse Negl. 2002; 26: 697–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, Labruna V. Child and adolescent abuse and neglect research: A review of the past 10 years. Part I: Physical and emotional abuse and neglect. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999; 38: 1214–1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Part I: Physical and emotional abuse and neglect. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999; 38: 1214–1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Martins CMS, Von WB, De CT, Juruena Francisco M. Emotional abuse in childhood is a differential factor for the development of depression in adults. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2014; 202: 774–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Thombs BD, Bernstein DP, Ziegelstein RC et al. An evaluation of screening questions for childhood abuse in 2 community samples: Implications for clinical practice. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006; 166: 2020–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Grandin LD, Alloy LB, Abramson LY. The social zeitgeber theory, circadian rhythms, and mood disorders: Review and evaluation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006; 26: 679–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Weiss RB, Stange JP, Boland EM et al. Kindling of life stress in bipolar disorder: Comparison of sensitization and autonomy models. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2015; 124: 4–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Cobb S. Presidential address‐1976. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976; 38: 300–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Miklowitz DJ, Wisniewski SR, Miyahara S, Otto MW, Sachs GS. Perceived criticism from family members as a predictor of the one‐year course of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2005; 136: 101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Tohen M, Frank E, Bowden CL et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force report on the nomenclature of course and outcome in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2009; 11: 453–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Environmental Risk Factors for Bipolar Disorders and High-Risk States in Adolescence: A Systematic Review

1. Connor D.F., Ford J.D., Pearson G.S., Scranton V.L., Dusad A. Early-Onset Bipolar Disorder: Characteristics and Outcomes in the Clinic. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2017;27:875–883. doi: 10. 1089/cap.2017.0058. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1089/cap.2017.0058. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Geoffroy P.A., Etain B., Jamain S., Bellivier F., Leboyer M. Early onset bipolar disorder: Validation from admixture analyses and biomarkers. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2013;58:240–248. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800410. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Vieta E., Salagre E., Grande I., Carvalho A.F., Fernandes B.S., Berk M., Birmaher B., Tohen M., Suppes T. Early intervention in Bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2018;175:411–426. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17090972. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Baldessarini R.J., Bolzani L., Cruz N., Jones P.B., Lai M., Lepri B., Perez J., Salvatore P., Tohen M., Tondo L. Onset-age of bipolar disorders at six international sites. J. Affect. Disord. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.030. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Altamura A.C., Buoli M., Albano A., Dell’Osso B. Age at onset and latency to treatment (duration of untreated illness) in patients with mood and anxiety disorders: A naturalistic study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:172–179. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3283384c74. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:172–179. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3283384c74. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Drancourt N., Etain B., Lajnef M., Henry C., Raust A., Cochet B., Mathieu F., Gard S., M’Bailara K., Zanouy L., et al. Duration of untreated bipolar disorder: Missed opportunities on the long road to optimal treatment. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013;127:136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01917.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Koenders M.A., Mesman E., Giltay E.J., Elzinga B.M., Hillegers M.H.J. Traumatic experiences, family functioning, and mood disorder development in bipolar offspring. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020;59:277–289. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Kim H.-I., Lee H.-J., Cho C.-H., Kang S.-G., Yoon H.-K., Park Y.-M., Lee S.-H., Moon J.-H., Song H.-M., Lee E., et al. Association of CLOCK, ARNTL, and NPAS2 gene polymorphisms and seasonal variations in mood and behavior. Chronobiol. Int. 2015;32:785–791. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2015.1049613. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2015;32:785–791. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2015.1049613. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Craddock N., Sklar P. Genetics of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013;381:1654–1662. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60855-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Uher R. Gene-environment interactions in severe mental illness. Front. Psychiatry. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00048. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Khan A., Plana-Ripoll O., Antonsen S., Brandt J., Geels C., Landecker H., Sullivan P.F., Pedersen C.B., Rzhetsky A. Environmental pollution is associated with increased risk of psychiatric disorders in the US and Denmark. PLoS Biol. 2019;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Marrie R.A., Reingold S., Cohen J., Stuve O., Trojano M., Sorensen P.S., Cutter G., Reider N. The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Mult. Scler. J. 2015;21:305–317. doi: 10.1177/1352458514564487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1177/1352458514564487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Leo R.J., Singh J. Migraine headache and bipolar disorder comorbidity: A systematic review of the literature and clinical implications. Scand. J. Pain. 2016;11:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2015.12.002. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Šprah L., Dernovšek M.Z., Wahlbeck K., Haaramo P. Psychiatric readmissions and their association with physical comorbidity: A systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1172-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Agnew-Blais J., Danese A. Childhood maltreatment and unfavourable clinical outcomes in bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:342–349. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00544-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Sutterland A.L., Fond G., Kuin A., Koeter M.W.J., Lutter R., van Gool T., Yolken R., Szoke A., Leboyer M., De Haan L. Beyond the association. Toxoplasma gondii in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and addiction: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2015;132:161–179. doi: 10.1111/acps.12423. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Beyond the association. Toxoplasma gondii in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and addiction: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2015;132:161–179. doi: 10.1111/acps.12423. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Janiri D., Sani G., Rossi P., Piras F., Iorio M., Banaj N., Giuseppin G., Spinazzola E., Maggiora M., Ambrosi E., et al. Amygdala and hippocampus volumes are differently affected by childhood trauma in patients with bipolar disorders and healthy controls. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19:353–362. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12516. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Janiri D., Sani G., De Rossi P., Piras F., Banaj N., Ciullo V., Simonetti A., Arciniegas D.B., Spalletta G. Hippocampal subfield volumes and childhood trauma in bipolar disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;253:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.071. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Raballo A., Mechelli A., Menculini G., Tortorella A. Risk syndromes in psychiatry: A state-of-the-art overview. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2019;2:7–14. doi: 10.12740/APP/109506. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2019;2:7–14. doi: 10.12740/APP/109506. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Bortolato B., Köhler C.A., Evangelou E., León-Caballero J., Solmi M., Stubbs B., Belbasis L., Pacchiarotti I., Kessing L.V., Berk M., et al. Systematic assessment of environmental risk factors for bipolar disorder: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19:84–96. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12490. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Marangoni C., Hernandez M., Faedda G.L. The role of environmental exposures as risk factors for bipolar disorder: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;193:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.055. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Wells G.A., Shea B., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];2014 Available online: www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Wells G.A., Shea B., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];2014 Available online: www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

24. Herzog R., Álvarez-Pasquin M.J., Díaz C., Del Barrio J.L., Estrada J.M., Gil Á. Are healthcare workers intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Romero S., Birmaher B., Axelson D.A., Iosif A.M., Williamson D.E., Gill M.K., Goldstein B.I., Strober M.A., Hunt J., Goldstein T.R., et al. Negative life events in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2009;70:1452–1460. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04948gre. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Romero S., Birmaher B., Axelson D. , Goldstein T., Goldstein B.I., Gill M.K., Iosif A.-M., Strober M.A., Hunt J., Esposito-Smythers C. Prevalence and correlates of physical and sexual abuse in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2009;112:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Goldstein T., Goldstein B.I., Gill M.K., Iosif A.-M., Strober M.A., Hunt J., Esposito-Smythers C. Prevalence and correlates of physical and sexual abuse in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2009;112:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Bakare M.O., Agomoh A.O., Eaton J., Ebigbo P.O., Onwukwe J.U. Functional status and its associated factors in Nigerian adolescents with bipolar disorder. Afr. J. Psychiatry. 2011;14:388–391. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v14i5.7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Shaffer D., Gould M.S., Brasic J., Fisher P., Aluwahlia S., Bird H. A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1983 doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Goldstein T.R., Birmaher B., Axelson D., Goldstein B.I., Gill M.K., Esposito-Smythers C., Ryan N.D., Strober M.A., Hunt J., Keller M. Family environment and suicidal ideation among bipolar youth. Arch. Suicide Res. 2009;13:378–388. doi: 10.1080/13811110903266699. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Arch. Suicide Res. 2009;13:378–388. doi: 10.1080/13811110903266699. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Olson D.H., Portner J., Bell R. FACES II: Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales. University of Minnesota; St. Paul, MN, USA: 1982. pp. 4–24. [Google Scholar]

31. Lau P., Hawes D.J., Hunt C., Frankland A., Roberts G., Wright A., Costa D.S., Mitchell P.B. Family environment and psychopathology in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;226:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Monck E., Dobbs R. Measuring life events in an adolescent population: Methodological issues and related findings. Psychol. Med. 1985;15:841–850. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700005079. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Kemner S.M., Mesman E., Nolen W.A., Eijckemans M.J.C., Hillegers M.H.J. The role of life events and psychological factors in the onset of first and recurrent mood episodes in bipolar offspring: Results from the Dutch Bipolar Offspring Study. Psychol. Med. 2015;45:2571–2581. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000495. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychol. Med. 2015;45:2571–2581. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000495. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Doucette S., Levy A., Flowerdew G., Horrocks J., Grof P., Ellenbogen M., Duffy A. Early parent–child relationships and risk of mood disorder in a Canadian sample of offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder: Findings from a 16-year prospective cohort study. Early Interv. Psychiatry. 2016;10:381–389. doi: 10.1111/eip.12195. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Reichart C.G., Van Der Ende J., Hillegers M.H.J., Wals M., Bongers I.L., Nolen W.A., Ormel J., Verhulst F.C. Perceived parental rearing of bipolar offspring. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2007;115:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00838.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Ferreira G.S., Moreira C.R.L., Kleinman A., Nader E.C.G.P., Gomes B.C., Teixeira A.M.A., Rocca C.C.A., Nicoletti M., Soares J.C., Busatto G.F., et al. Dysfunctional family environment in affected versus unaffected offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2013;47:1051–1057. doi: 10.1177/0004867413506754. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2013;47:1051–1057. doi: 10.1177/0004867413506754. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Hillegers M.H.J., Burger H., Wals M., Reichart C.G., Verhulst F.C., Nolen W.A., Ormel J. Impact of stressful life events, familial loading and their interaction on the onset of mood disorders: Study in a high-risk cohort of adolescent offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;185:97–101. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.97. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Hanford L.C., Eckstrand K., Manelis A., Hafeman D.M., Merranko J., Ladouceur C.D., Graur S., McCaffrey A., Monk K., Bonar L.K., et al. The impact of familial risk and early life adversity on emotion and reward processing networks in youth at-risk for bipolar disorder. PLoS ONE. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Pan L.A., Goldstein T.R., Rooks B.T., Hickey M., Fan J.Y., Merranko J., Monk K., Diler R.S., Sakolsky D. J., Hafeman D., et al. The relationship between stressful life events and Axis i diagnoses among adolescent offspring of probands with bipolar and non-bipolar psychiatric disorders and healthy controls: The Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2017;78:e234–e243. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J., Hafeman D., et al. The relationship between stressful life events and Axis i diagnoses among adolescent offspring of probands with bipolar and non-bipolar psychiatric disorders and healthy controls: The Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2017;78:e234–e243. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Duffy A., Alda M., Trinneer A., Demidenko N., Grof P., Goodyer I.M. Temperament, life events, and psychopathology among the offspring of bipolar parents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2007;16:222–228. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0592-x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Joyce K., Thompson A., Marwaha S. Is treatment for bipolar disorder more effective earlier in illness course? A comprehensive literature review. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2016;4 doi: 10.1186/s40345-016-0060-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Van Meter A.R., Burke C., Youngstrom E.A., Faedda G.L., Correll C. U. The Bipolar Prodrome: Meta-Analysis of Symptom Prevalence Prior to Initial or Recurrent Mood Episodes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2016;55:543–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.017. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

U. The Bipolar Prodrome: Meta-Analysis of Symptom Prevalence Prior to Initial or Recurrent Mood Episodes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2016;55:543–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.017. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. DelBello M.P. A Risk Calculator for Bipolar Disorder in Youth: Improving the Odds for Personalized Prevention and Early Intervention? J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2018;57:725–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.871. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Tsuchiya K.J., Byrne M., Mortensen P.B. Risk factors in relation to an emergence of bipolar disorder: A systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:231–242. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00038.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Koenders M.A., Giltay E.J., Spijker A.T., Hoencamp E., Spinhoven P., Elzinga B.M. Stressful life events in bipolar i and II disorder: Cause or consequence of mood symptoms? J. Affect. Disord. 2014;161:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.036. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Birmaher B., Merranko J.A., Goldstein T.R., Gill M.K., Goldstein B.I., Hower H., Yen S., Hafeman D., Strober M., Diler R.S., et al. A Risk Calculator to Predict the Individual Risk of Conversion From Subthreshold Bipolar Symptoms to Bipolar Disorder I or II in Youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2018;57:755–763.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.05.023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Birmaher B., Merranko J.A., Goldstein T.R., Gill M.K., Goldstein B.I., Hower H., Yen S., Hafeman D., Strober M., Diler R.S., et al. A Risk Calculator to Predict the Individual Risk of Conversion From Subthreshold Bipolar Symptoms to Bipolar Disorder I or II in Youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2018;57:755–763.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.05.023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Hafeman D.M., Merranko J., Goldstein T.R., Axelson D., Goldstein B.I., Monk K., Hickey M.B., Sakolsky D., Diler R., Iyengar S., et al. Assessment of a person-level risk calculator to predict new-onset bipolar spectrum disorder in youth at familial risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1763. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Mourão-Miranda J., Oliveira L., Ladouceur C.D., Marquand A., Brammer M., Birmaher B., Axelson D., Phillips M.L. Pattern recognition and functional neuroimaging help to discriminate healthy adolescents at risk for mood disorders from low risk adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029482. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029482. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Sugranyes G., Solé-Padullés C., de la Serna E., Borras R., Romero S., Sanchez-Gistau V., Garcia-Rizo C., Goikolea J.M., Bargallo N., Moreno D., et al. Cortical Morphology Characteristics of Young Offspring of Patients With Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2017;56:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.09.516. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Goodday S.M., Horrocks J., Keown-Stoneman C., Grof P., Duffy A. Repeated salivary daytime cortisol and onset of mood episodes in offspring of bipolar parents. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2016;4 doi: 10.1186/s40345-016-0053-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Singh M.K., Jo B., Adleman N.E., Howe M., Bararpour L., Kelley R.G., Spielman D., Chang K.D. Prospective neurochemical characterization of child offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging. 2013;214:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.05.005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Neuroimaging. 2013;214:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.05.005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Geoffroy P.A., Scott J. Prodrome or risk syndrome: What’s in a name? Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2017;5:7. doi: 10.1186/s40345-017-0077-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Jacka F.N., Mykletun A., Berk M. Moving towards a population health approach to the primary prevention of common mental disorders. BMC Med. 2012;10 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Berk M., Moylan S., Jacka F.N. A Royal gift to prevention efforts. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2014;48:110–111. doi: 10.1177/0004867413493524. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Etain B., Mathieu F., Henry C., Raust A., Roy I., Germain A., Leboyer M., Bellivier F. Preferential association between childhood emotional abuse and bipolar disorder. J. Trauma. Stress. 2010;23:376–383. doi: 10.1002/jts.20532. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Rakofsky J.J., Ressler K.J., Dunlop B.W. BDNF function as a potential mediator of bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity. Mol. Psychiatry. 2012;17:22–35. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Librenza-Garcia D., Suh J.S., Watts D.P., Ballester P.L., Minuzzi L., Kapczinski F., Frey B.N. Structural and Functional Brain Correlates of Neuroprogression in Bipolar Disorder. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1007/7854_2020_177. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Harnett N.G., Goodman A.M., Knight D.C. PTSD-related neuroimaging abnormalities in brain function, structure, and biochemistry. Exp. Neurol. 2020;330:113331. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113331. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Barron E., Sharma A., Le Couteur J., Rushton S., Close A., Kelly T., Grunze H., Ferrier I.N., Le Couteur A. Family environment of bipolar families: A UK study. J. Affect. Disord. 2014;152–154:522–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.016. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Affect. Disord. 2014;152–154:522–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.016. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. Tole F., Kopf J., Schröter K., Palladino V.S., Jacob C.P., Reif A., Kittel-Schneider S. The role of pre-, peri-, and postnatal risk factors in bipolar disorder and adult ADHD. J. Neural. Transm. 2019;126:1117–1126. doi: 10.1007/s00702-019-01983-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

61. Miklowitz D.J., Schneck C.D., George E.L., Taylor D.O., Sugar C.A., Birmaher B., Kowatch R.A., DelBello M.P., Axelson D.A. Pharmacotherapy and family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar I and II disorders: A 2-year randomized trial. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;171:658–667. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Miklowitz D.J., Chung B. Family-Focused Therapy for Bipolar Disorder: Reflections on 30 Years of Research. Fam. Process. 2016 doi: 10.1111/famp.12237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Kessing L.V., Vradi E., McIntyre R.S., Andersen P.K. Causes of decreased life expectancy over the life span in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;180:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.027. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Kessing L.V., Vradi E., McIntyre R.S., Andersen P.K. Causes of decreased life expectancy over the life span in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;180:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.027. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Correll C.U., Solmi M., Veronese N., Bortolato B., Rosson S., Santonastaso P., Thapa-Chhetri N., Fornaro M., Gallicchio D., Collantoni E., et al. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: A large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:163–180. doi: 10.1002/wps.20420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Bernardini F., Attademo L., Trezzi R., Gobbicchi C., Balducci P.M., Del Bello V., Menculini G., Pauselli L., Piselli M., Sciarma T., et al. Air pollutants and daily number of admissions to psychiatric emergency services: Evidence for detrimental mental health effects of ozone. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019;29:e66. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000623. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatr. Sci. 2019;29:e66. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000623. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

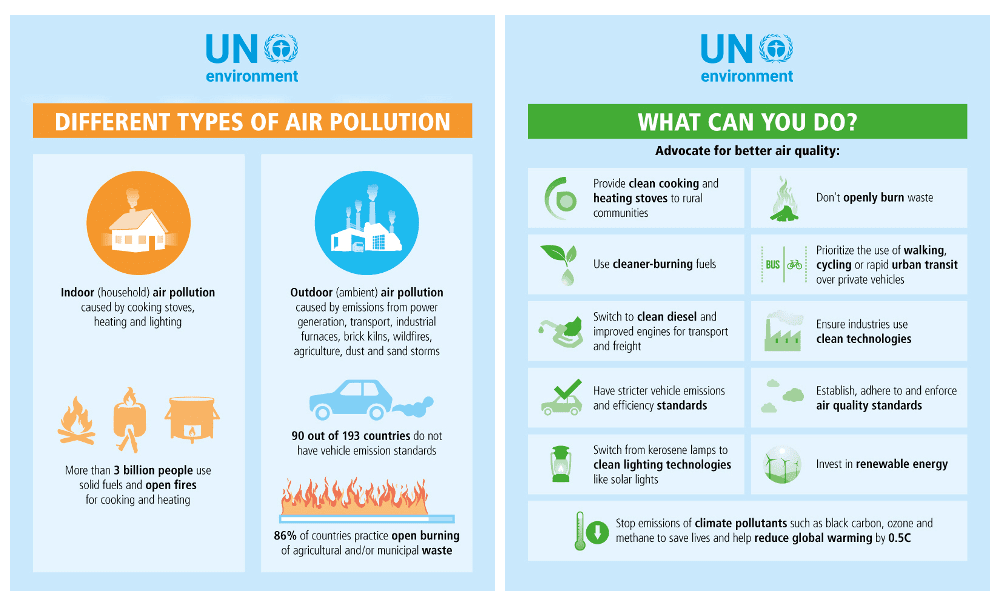

Mental disorders linked to air pollution

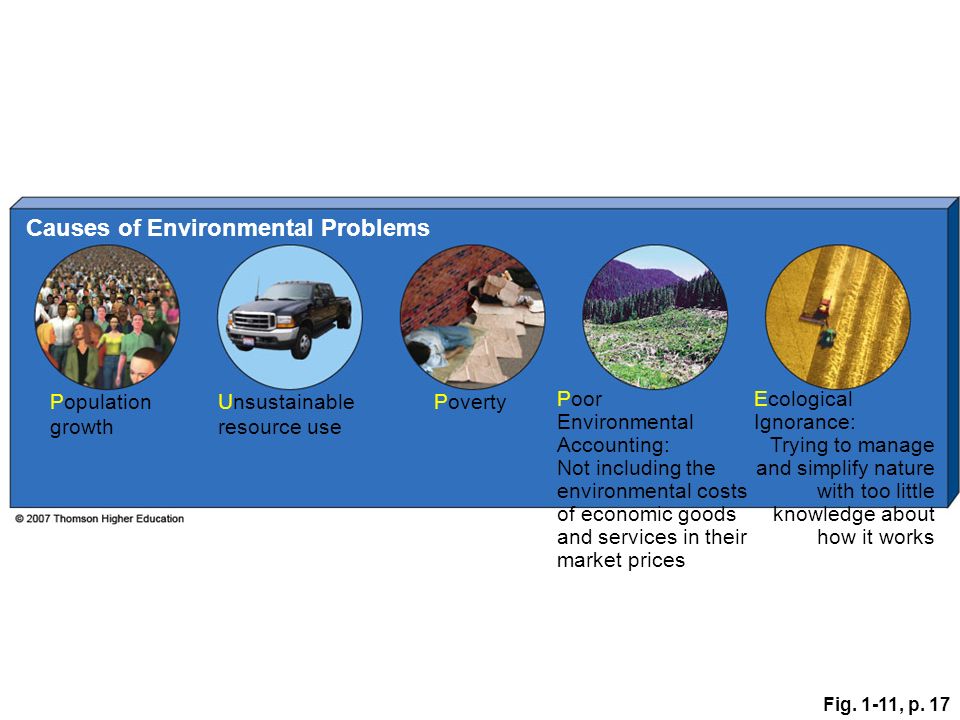

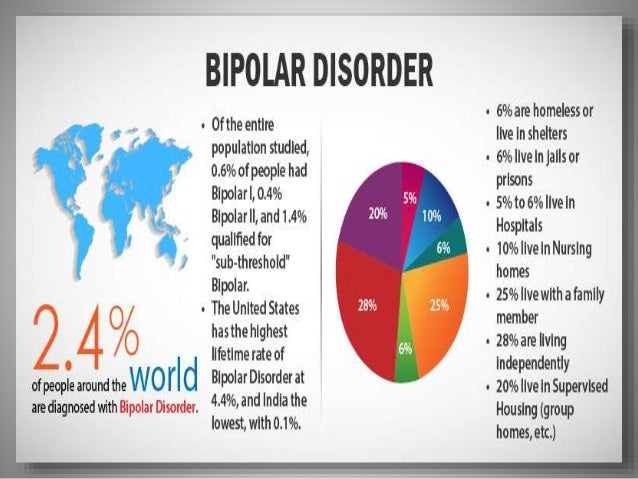

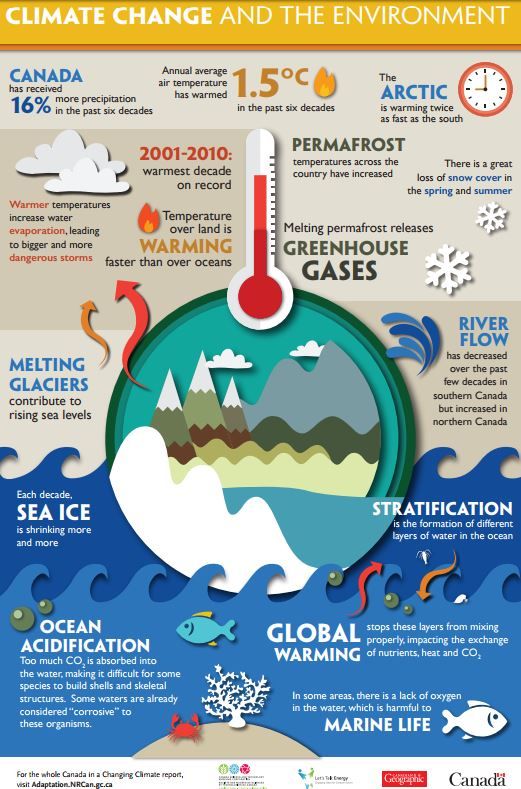

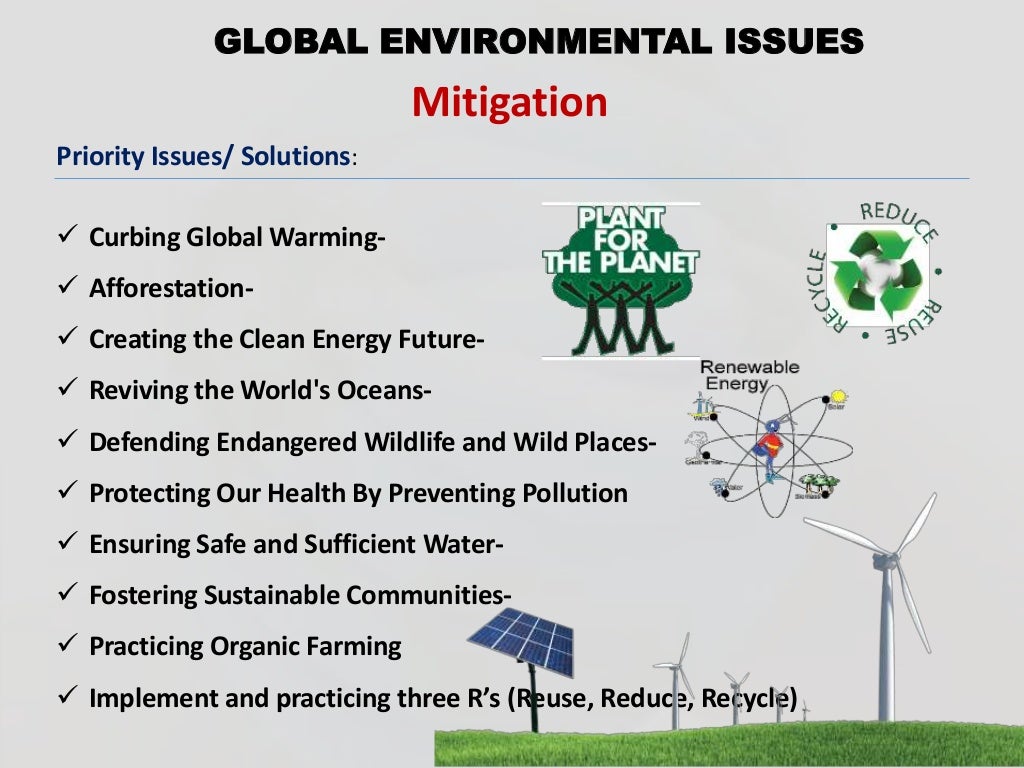

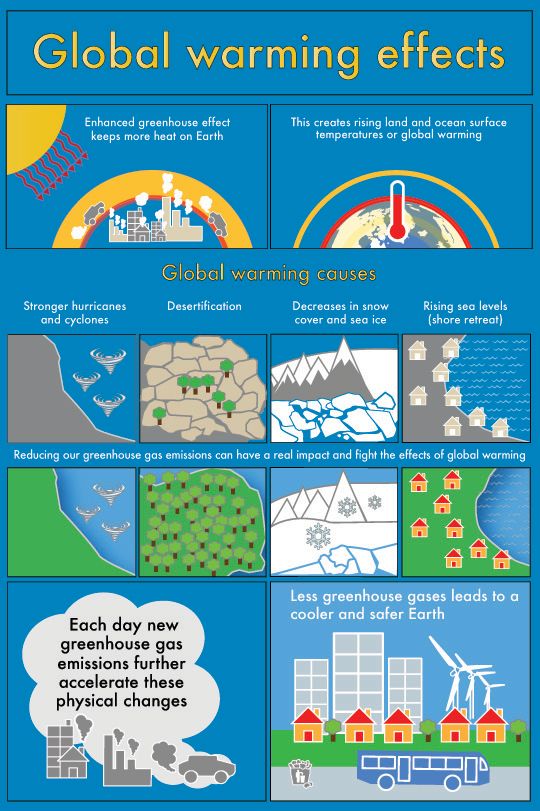

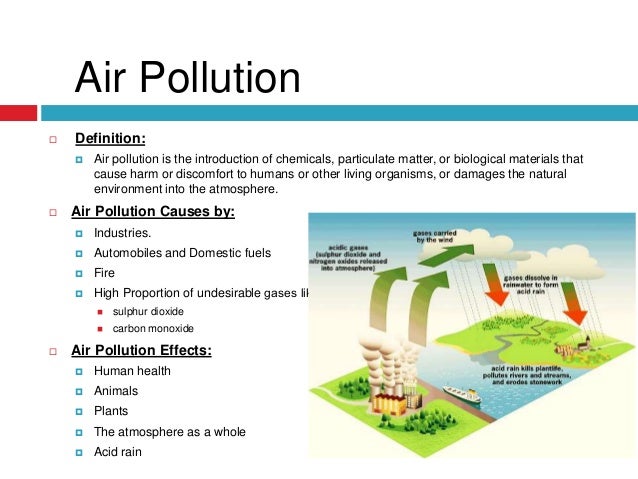

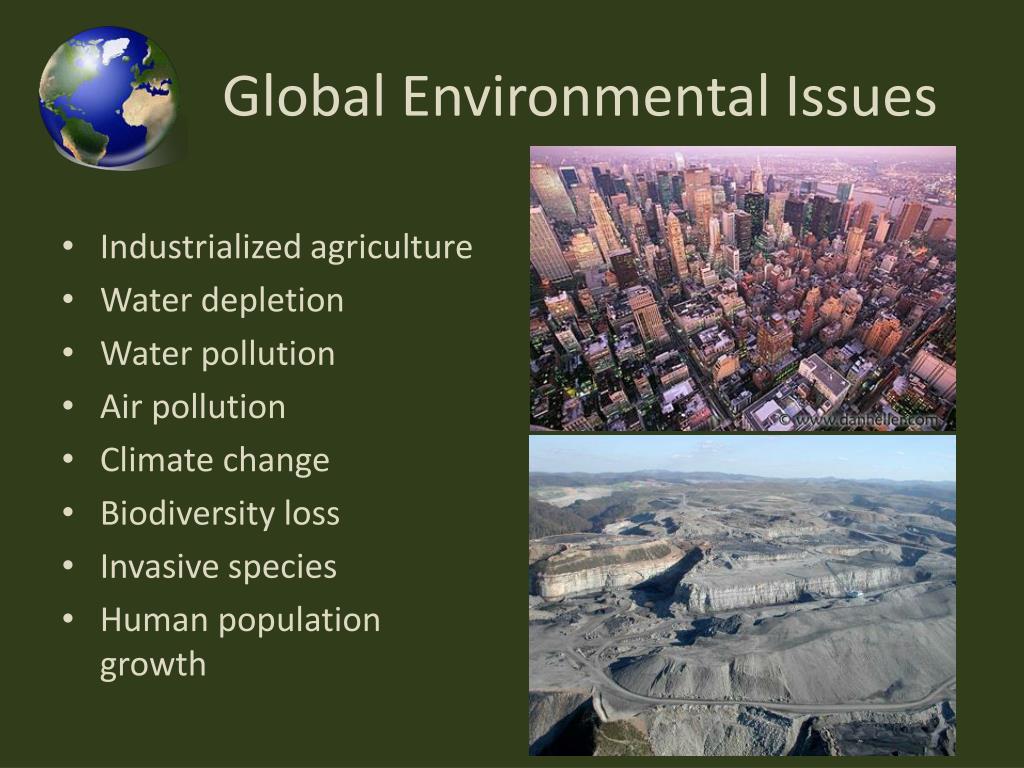

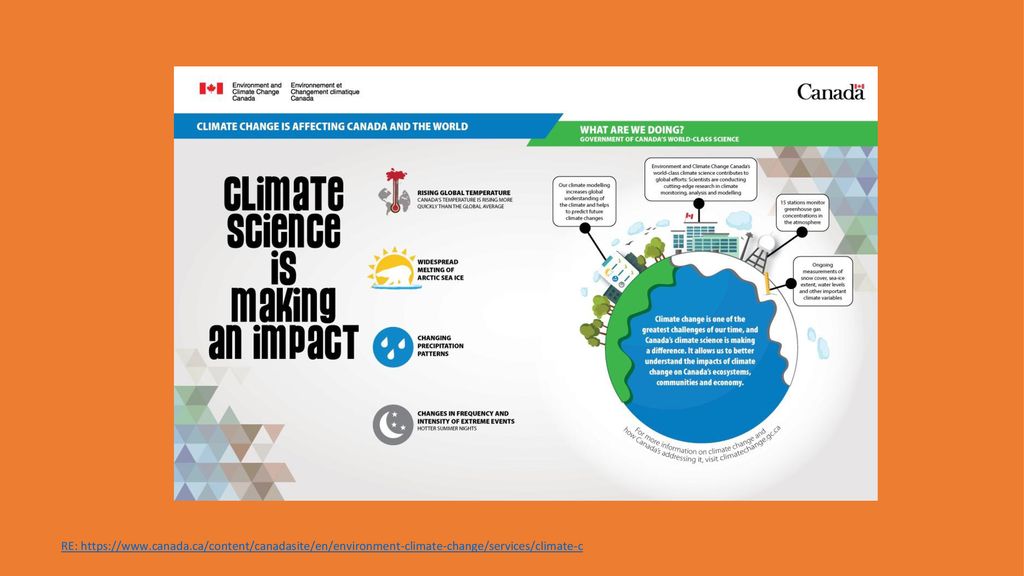

Scientists revealed a correlation between the development mental disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder, and air pollution says in PLoS Biology . They are conducted research on large samples of 151 million US residents and 1.44 million people in Denmark.

By According to WHO, polluted air is cause of death of seven million people in year. According to a study published last year, it shortens life on average Russians for about nine months. Harmful substances in the atmosphere affect and on people's mental health. The researchers found that children with mental retarded and suffering from adolescence with psychosis are more likely to live in areas with polluted air. As shown metastudy of 14 million couples twins, at risk bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and schizophrenia not only genetic factors but also the conditions surrounding the person, in including bad environment. However scientists started in detail explore the relationship between the occurrence mental and neurological diseases and environmental pollution only recently. nine0005

However scientists started in detail explore the relationship between the occurrence mental and neurological diseases and environmental pollution only recently. nine0005

American and Danish doctors led by Andrey Rzhetsky (Andrey Rzhetsky) from the University of Chicago decided to study the relationship between the occurrence of mental and neurological disorders and environmental pollution. Study they conducted on two large samples. The first sample was based on the IBM database MarketScan, it included 151 million US residents under 65 years of age, who in 2003-2013 turned to doctors of any profile on medical insurance. because of large sample size study carried out at the district level. These are territorial units, smaller than larger than a state, but larger than a city. The researchers compared the quality air, water, land and security level in houses (passing nearby streets and highways, pedestrian safety) in each county with a level of one of six diseases - big depressive disorder, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, disorders personality, Parkinson's disease and epilepsy. Same the authors took into account the socio-demographic characteristics such as median county income, population density and number of cities. Pollution Data provided by the Protection Agency US environment. In particular, for air, 87 potential pollutants, for water - 80, for land — 26.

Same the authors took into account the socio-demographic characteristics such as median county income, population density and number of cities. Pollution Data provided by the Protection Agency US environment. In particular, for air, 87 potential pollutants, for water - 80, for land — 26.

Other the sample consisted of 1.44 million inhabitants of Denmark, born in 1979-2002 and lived for the first 10 years in the country. The authors analyzed dependence of the development of four mental illnesses (major depressive disorder, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, disorders personality) depending on from air pollution. Its quality was calculated according to 14 indicators. In this case, the authors examined the health status of individuals, and not regions of the country.

The scientists analyzed the results using the distribution Poisson which allows us to estimate the probability occurrence of events for specific time, and Cox's regression, which makes it possible to predict the risk occurrence of any event. nine0005

nine0005

It turned out that in the United States a high correlation was observed between the occurrence of two mental disorders and air pollution. Residents in the most polluted counties are at risk of bipolar disorder was at 27 percent ( p < 10 -4 ) higher, and the risk of a large depressive disorder six percent higher ( p = 0.05), than in areas with clean air. Risk of Personality Disorder correlated with soil pollution: in the dirtiest counties compared to the more prosperous, it was 19percent higher ( p < 10 -4 ). The links between the development of mental disorders and water pollution or safety level in the houses, the authors did not reveal. Same scientists have not found a link between pollution environment and the development of neurological diseases.

B Denmark correlation between pollution air and the emergence of mental disorders was even higher than in USA. Areas with the dirtiest air risk of major depression disorder was 50 percent higher schizophrenia by 148 percent, and disorders personality - 162 percent higher in compared to environmentally friendly regions of the country (everywhere p < 2×10 − 16 ). The risks of bipolar disorders in Denmark and the United States were are comparable: in areas of Denmark with strongly polluted air it was 29 percent higher ( p < 3×10 − 3 ).

The risks of bipolar disorders in Denmark and the United States were are comparable: in areas of Denmark with strongly polluted air it was 29 percent higher ( p < 3×10 − 3 ).

Authors conclude that further research mental disorders should be addressed attention to the ecology in the area where the participants of the experiments live, and not only for genetic factors. Revealed correlation does not mean that air pollution and mental diseases have a causal connection. To reveal it, additional research. nine0005

How show other scientific works, each the sixth death on the planet is associated with environmental pollution. More often All these are non-communicable diseases, such as heart attacks, lung cancer, strokes, that occur as a result of pollution air. How calculated scientists, in 2015 in Russia due to poor ecology, 170 thousand people died.

Ekaterina Rusakova

Found a typo? Select the fragment and press Ctrl+Enter.

Bipolar disorder0001

General summary

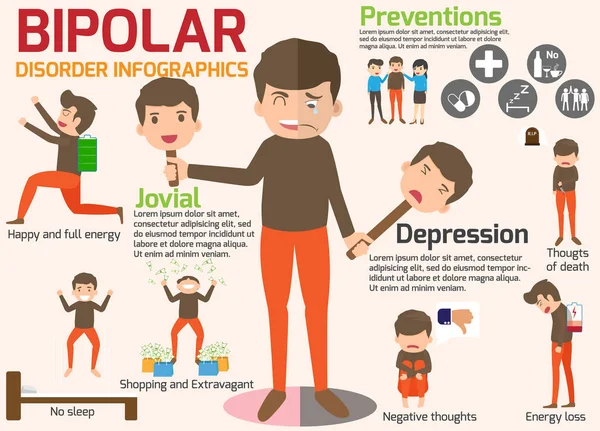

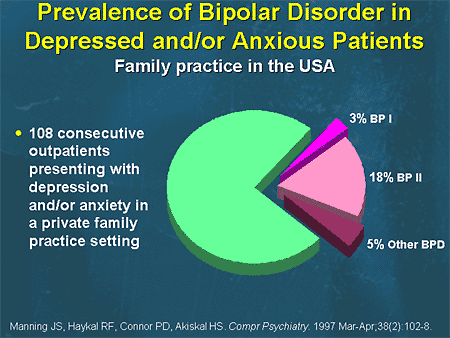

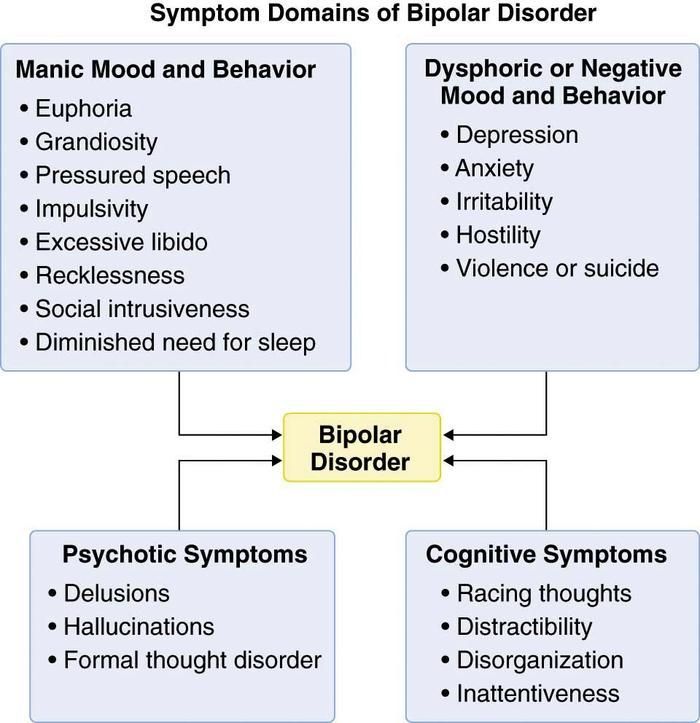

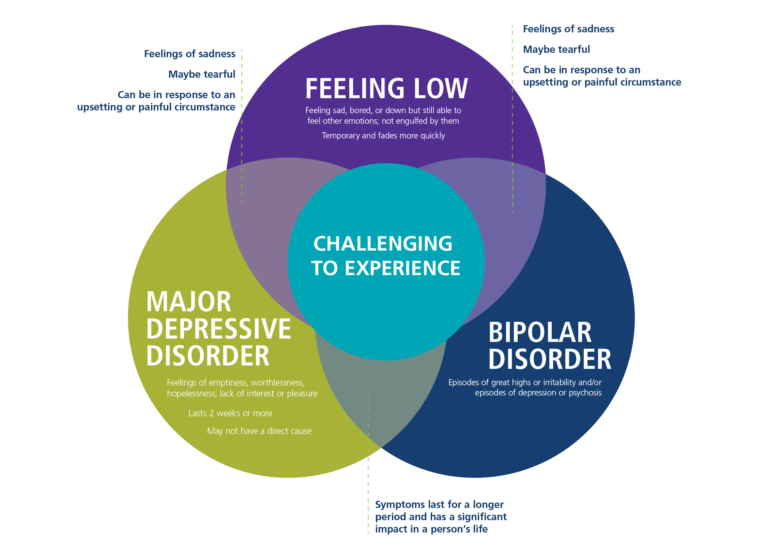

Bipolar disorder, also known as bipolar affective disorder (BAD) and formerly known as manic-depressive psychosis (PMD). It is a set of mood disorders characterized by marked fluctuations in mood, thinking, behaviour, energy and ability to perform daily activities.

A person suffering from this disorder alternates his state of mind between mania or hypomania - a phase of joy, exaltation, euphoria and grandiosity and depression, with sadness, inhibition and ideas of death. nine0005

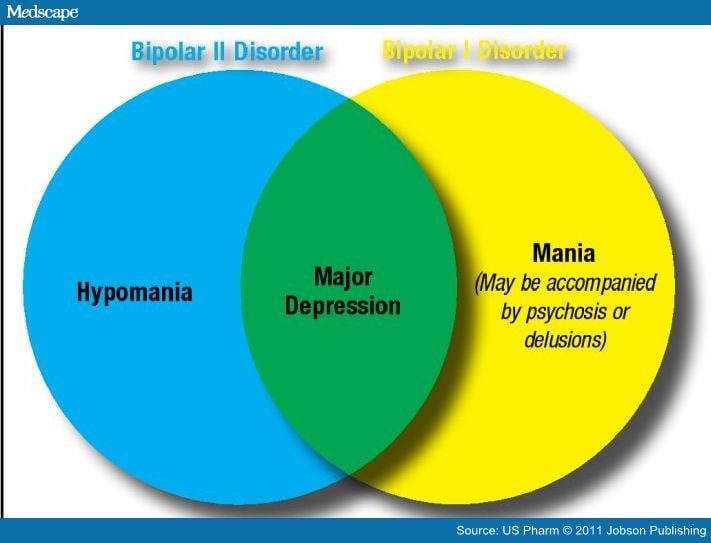

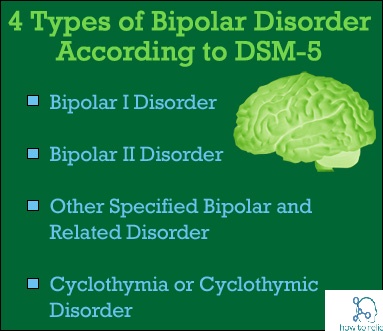

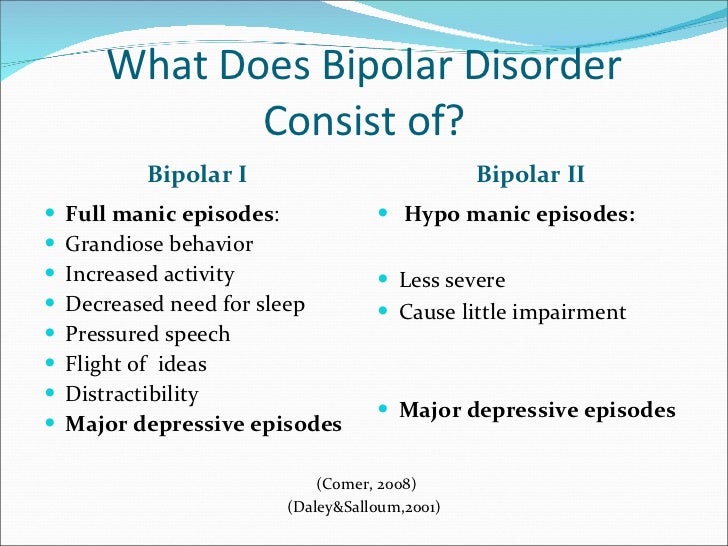

Four types of bipolar disorder were defined by severity and alternation of moods over time:

- Bipolar I disorder

- Bipolar disorder type II

- Cyclothymia

- Non-specific bipolar disorder

Because bipolar disorder occurs in young people, it has a high social cost. It is the second leading cause of disability worldwide. In addition, those who suffer from it pose a higher risk than the general population of deaths from suicide, homicide, accidents, and natural causes such as cardiovascular disease. nine0005

nine0005

In type 1, the person alternates between depressive episodes with full manic episodes, and in type 2, he alternates between depressive episodes and hypomanic (less severe) episodes.

The symptoms of this disorder are severe, different from the normal highs and lows of mood. These symptoms can lead to relationship problems, work, school, or even suicide.

During the depression phase a person may experience:

- Negative perception of life. nine0072

- Inability to feel the pleasure of life.

- No energy

- Self-criticism.

- In extreme cases, suicide.

During a manic phase a person may experience:

- Denial that there is a problem.

- Sudden change of mood.

- Irrational financial decisions.

- Feeling of great enthusiasm

- Don't think about the consequences of your actions.

- Lack of sleep nine0079

- Persistent sadness

- Lack of interest in engaging in pleasurable activities.

- Apathy or indifference.

- Anxiety or social anxiety.

- Chronic pain or irritability.

- Lack of motivation

- Guilt, hopelessness, social isolation.

- Lack of sleep or appetite. nine0072

- Suicidal thoughts

- In extreme cases, there may be psychotic symptoms: delusions or hallucinations are usually unpleasant.

- Great energy and activity.

- Some people may be more creative, while others may be more irritable. nine0072

- A person may feel so good that he denies that he is experiencing a state of hypomania.

- Talk quickly and smoothly.

- Accelerated thoughts.

- Agitation.

- Light condition. nine0072

- Impulsive and risky behavior.

- Excessive monetary expenses

- Hypersexuality.

- A person with mania may also experience lack of sleep and inadequate judgment.

- On the other hand, maniacs may have problems with alcohol or other substance abuse.

Although childhood onset occurs, the normal age of onset for type 1 is 18 years and for type 2 is 22 years.

About 10% of bipolar 2 cases develop into type 1.

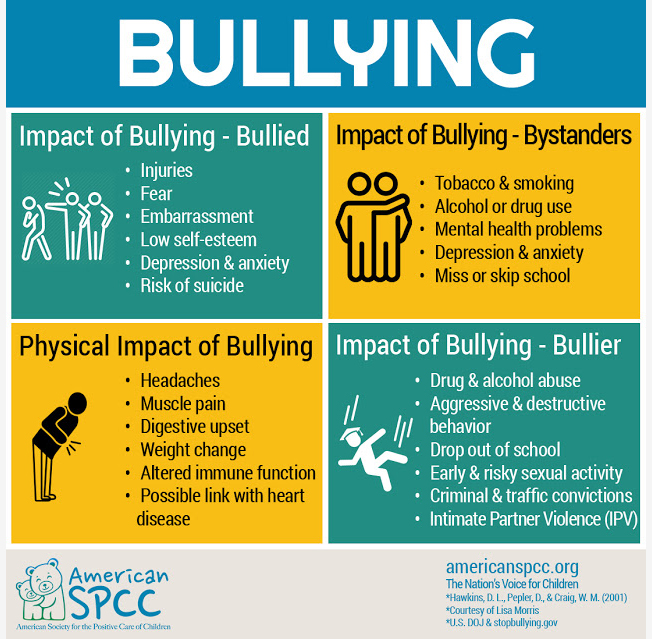

Although the causes are unclear, genetic and environmental factors (stress, childhood abuse) play a role.

Treatment usually includes psychotherapy, medication, sometimes electroconvulsive therapy may be helpful.

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of the depressive phase of bipolar disorder include:

Manic symptoms

Mania can occur in varying degrees:

Hypomania

This is the least severe degree of mania and lasts at least 4 days. This does not result in a noticeable decrease in a person's ability to work, communicate, or adapt.

This does not result in a noticeable decrease in a person's ability to work, communicate, or adapt.

He also does not require hospitalization and does not have psychotic characteristics. nine0005

In fact, overall functioning may improve during a hypomanic episode and is considered a natural anti-depression mechanism.

If an event of hypomania is not accompanied by or precedes depressive episodes, it is not considered a problem if the state of mind is uncontrollable.

Symptoms may last from several weeks to several months.

It is characterized by:

Mania

Mania is a period of euphoria and high mood for at least 7 days. If left untreated, a manic episode can last 3 to 6 months.

It is characterized by displaying three or more of the following behaviors:

In extreme cases, they may experience psychosis, so that contact with reality is broken, having a high state of mind.

It is common for a manic person to feel incomparable or indestructible and to feel chosen to realize a goal. nine0005

Approximately 50% of people with bipolar disorder experience hallucinations or delusions, which can lead to violent behavior or admission to a psychiatric hospital.

Mixed episodes

In bipolar disorder, a mixed episode is a condition in which mania and depression occur simultaneously.

People who experience this condition may have thoughts of grandiosity while having depressive symptoms such as suicidal thoughts or feelings of guilt. nine0005

nine0005

People who are in this state are at high risk of committing suicide because they confuse depressive emotions with mood swings or difficulty controlling impulsivity.

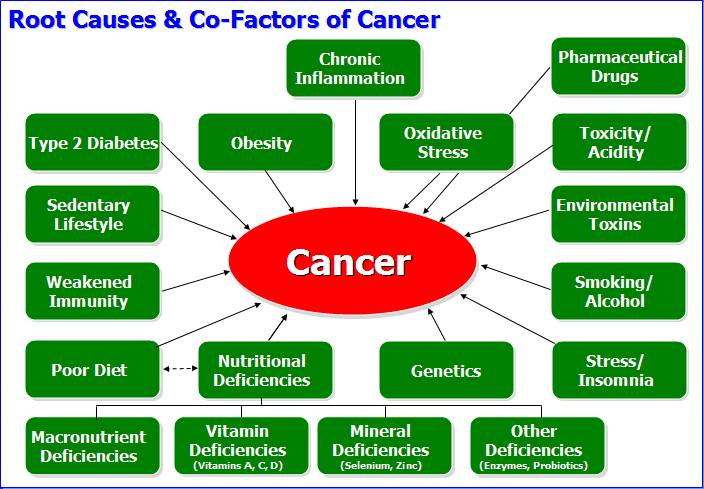

Causes

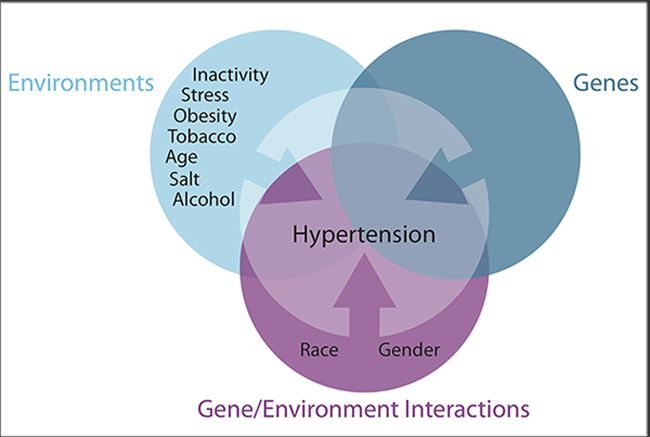

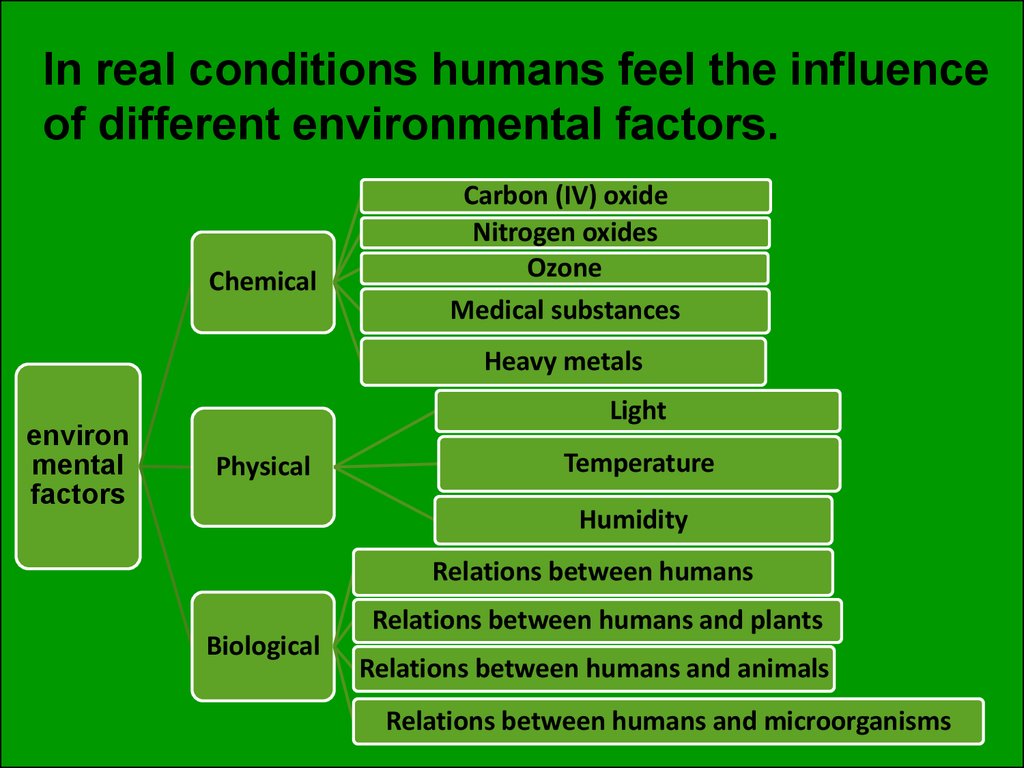

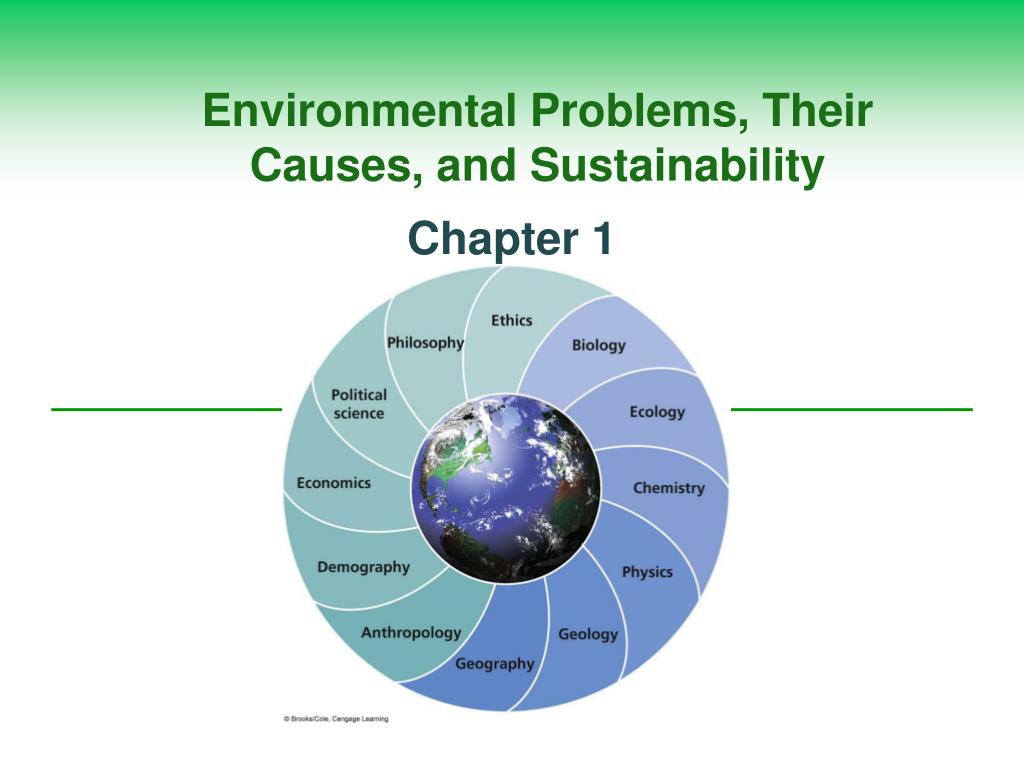

The exact causes of bipolar disorder are unclear, although they are thought to be largely genetic and environmental.

Genetic factors

It is believed that 60-70% of the risk of developing bipolarity depends on genetic factors. nine0005

Several studies have shown that certain genes and chromosomal regions are associated with susceptibility to develop the disorder, with each gene being more or less important.

The risk of bipolar disorder in people with family members with the same diagnosis is 10 times higher than in the general population.

Studies indicate heterogeneity, meaning that different genes are involved in different families.

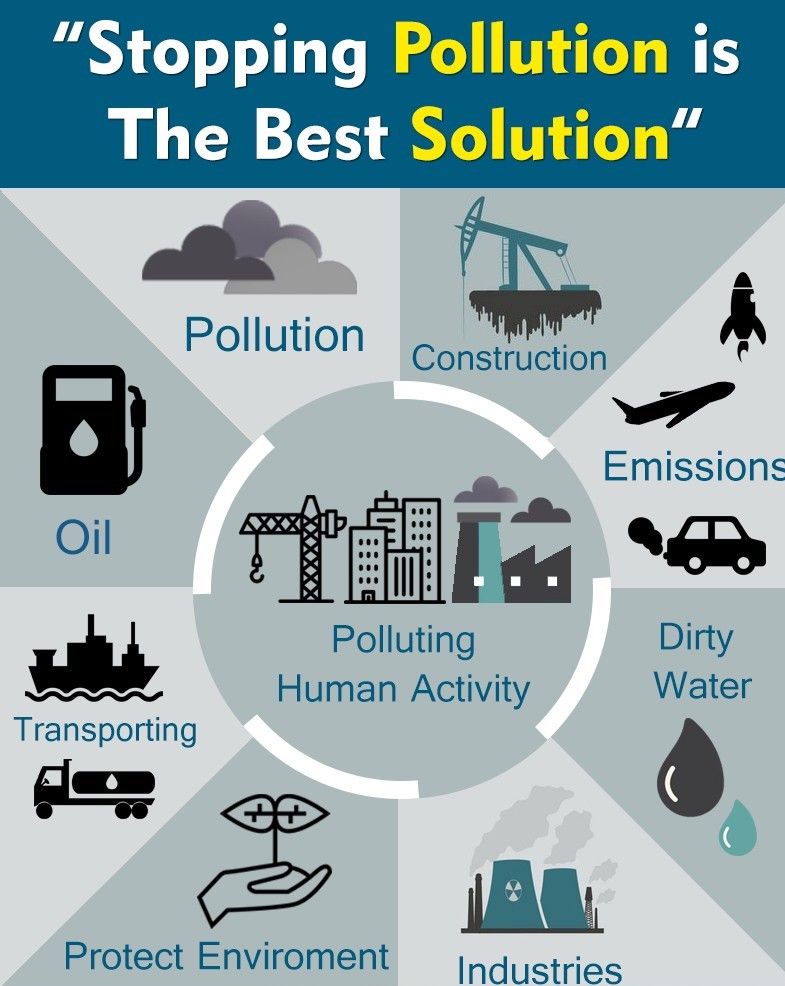

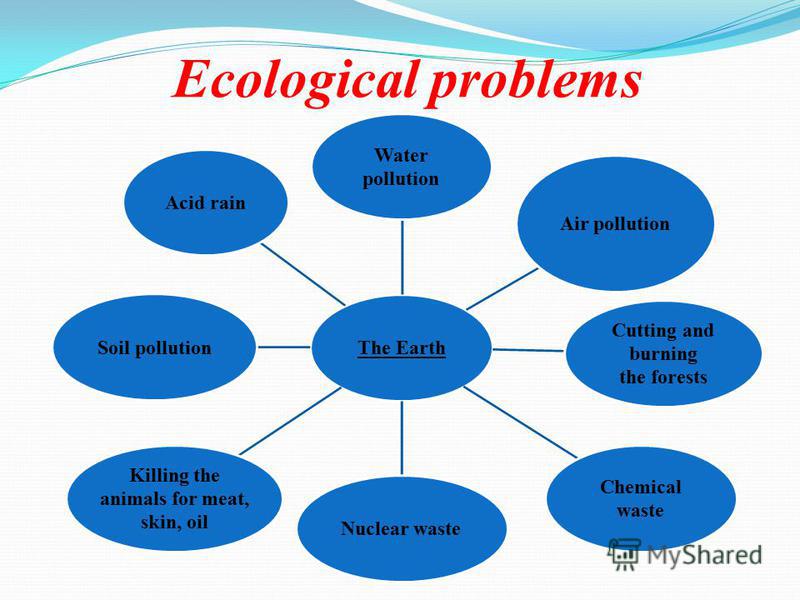

Environmental factors

Studies show that environmental factors play an important role in the development of bipolar disorder, and psychosocial variables may interact with genetic dispositions. nine0005

nine0005

Recent life events and interpersonal relationships contribute to manic and depressive episodes.

30-50% of adults diagnosed with bipolar disorder have been found to report abuse or trauma in childhood, which is associated with an earlier onset of the disorder and more suicide attempts.

Evolutionary factors

From evolutionary theory one might think that the negative effects that bipolar disorder can have on the ability to adapt cause genes not to be selected by natural selection. nine0005

However, there is still a high incidence of BD in many populations, so there may be some evolutionary benefit.

Doctors of evolutionary medicine suggest that high rates of BR throughout history suggest that the change between depressive and manic states suggested some evolutionary advantage in ancestral humans.

In highly stressed individuals, depressed mood can serve as a defense strategy to escape external stress, store energy, and increase sleep hours. nine0005

nine0005

Mania could benefit from her relationship with creativity, confidence, high energy levels and greater productivity.

Physiological, neurological and neuroendocrine factors

Brain imaging studies have shown differences in the volume of various brain areas between patients with bipolar disorder and healthy patients.

An increase in the volume of the lateral ventricles and an increase in the rate of white matter hyperintensity were found. nine0005

Magnetic resonance studies have shown that there is an abnormal modulation between the abdominal prefrontal region and the limbic regions, especially the amygdala. This will contribute to poor emotional regulation and mood-related symptoms.

On the other hand, there is evidence of an association between early stressful experiences and dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, leading to hyperactivation.

Less common bipolar disorder can result from trauma or a neurological condition: brain injury, stroke, HIV, multiple sclerosis, porphyria, and temporal lobe epilepsy. nine0005

nine0005

The neurotransmitter responsible for regulating mood, dopamine, has been found to increase its transmission during the manic phase and decrease during the depressive phase.

Glutamate increases in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during the manic phase.

Diagnosis

A patient must have at least two episodes of affective disorder to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder. At the same time, at least one of them must be either manic or mixed. For the correct diagnosis, the psychiatrist must take into account the characteristics of the patient's history, information received from his relatives. Currently, it is believed that the symptoms of bipolar disorder are characteristic of 1% of people, and in 30% of them the disease becomes a severe psychotic form. Determination of the severity of depression is carried out using special scales. The manic phase of bipolar disorder must be differentiated from arousal caused by the use of psychoactive substances, lack of sleep, or other causes, and the depressive phase from psychogenic depression. Psychopathy, neurosis, schizophrenia, as well as affective disorders and other psychoses due to somatic or nervous diseases should be excluded. nine0005

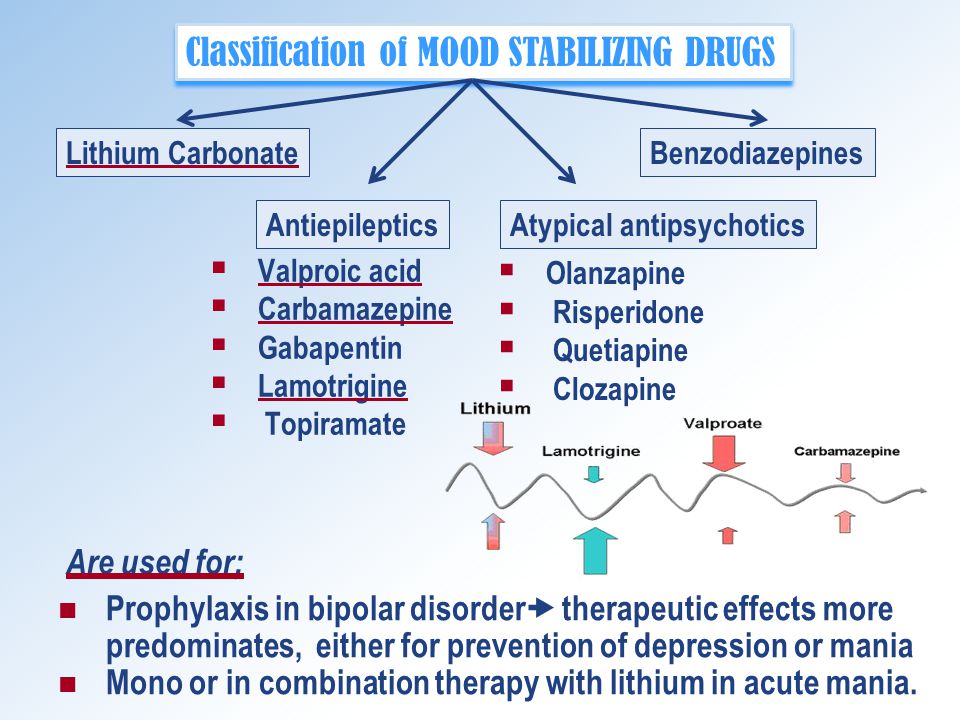

Methods of treatment

The main goal of the treatment of bipolar disorder is to normalize the mental state and mood of the patient, to achieve long-term remission. In severe cases of the disease, patients are hospitalized in the psychiatric department. Mild forms of the disorder can be treated on an outpatient basis. Antidepressants are used to relieve a depressive episode. The choice of a specific drug, its dosage and frequency of administration in each case is determined by a psychiatrist, taking into account the age of the patient, the severity of depression, and the possibility of its transition to mania. If necessary, the appointment of antidepressants is supplemented with mood stabilizers or antipsychotics. Antidepressants help to stop depressive states in bipolar disorder. Drug treatment of bipolar disorder in the stage of mania is carried out by normotimics, and in severe cases of the disease, antipsychotics are additionally prescribed.