Encopresis without constipation

Soiling (Encopresis) - HealthyChildren.org

My child is way past toilet training, but he still soils his underwear. What should I do?

Encopresis is one of the more frustrating disorders of middle childhood. It is the passing of stools into the underwear or pajamas, far past the time of normal toilet training. Encopresis affects about 1.5 percent of young school children and can create tremendous anxiety and embarrassment for children and their families.

Encopresis is not a disease but rather a symptom of a complex relationship between the body and psychological/environmental stresses. Boys with encopresis outnumber girls by a ratio of six to one, although the reasons for this greater prevalence among males is not known. The condition is not related to social class, family size, the child's position in the family or the age of the parents.

Two types

Doctors divide cases of encopresis into two categories: primary and secondary. Children with the primary disorder have had continuous soiling throughout their lives, without any period in which they were successfully toilet trained. By contrast, children with the secondary form may develop this condition after they have been toilet trained, such as upon entering school or encountering other experiences that might be stressful.

A frustrating condition

Children, parents, grandparents, teachers and friends alike are often baffled by this problem. Adults sometimes assume that the child is soiling himself on purpose. While this may not be the case, children can play an active role in managing the processes involved in this disorder.

The physical aspects of encopresis

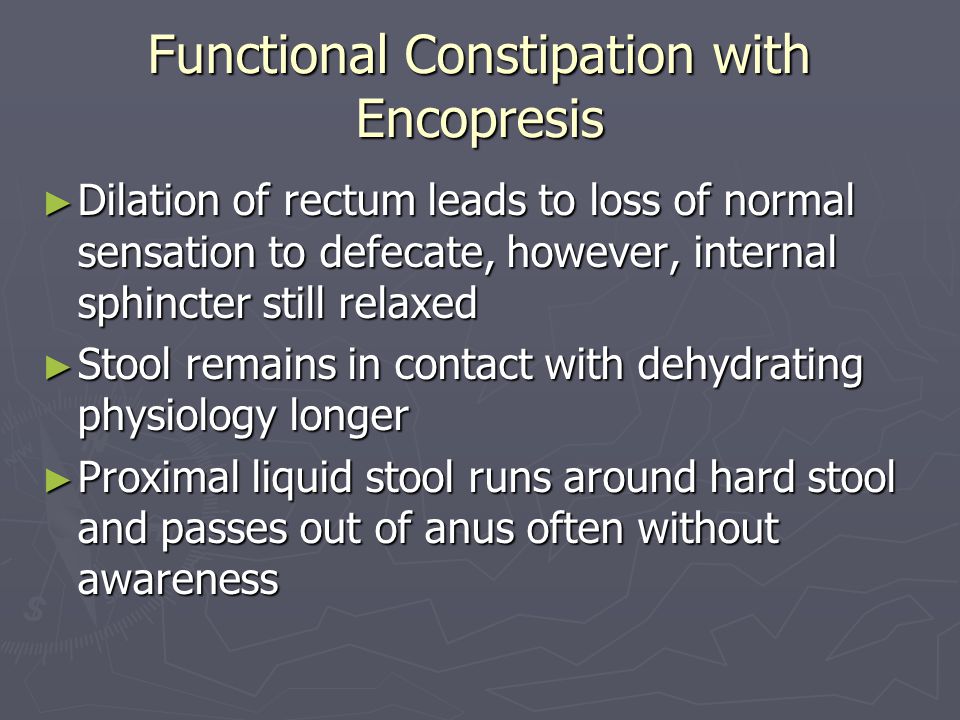

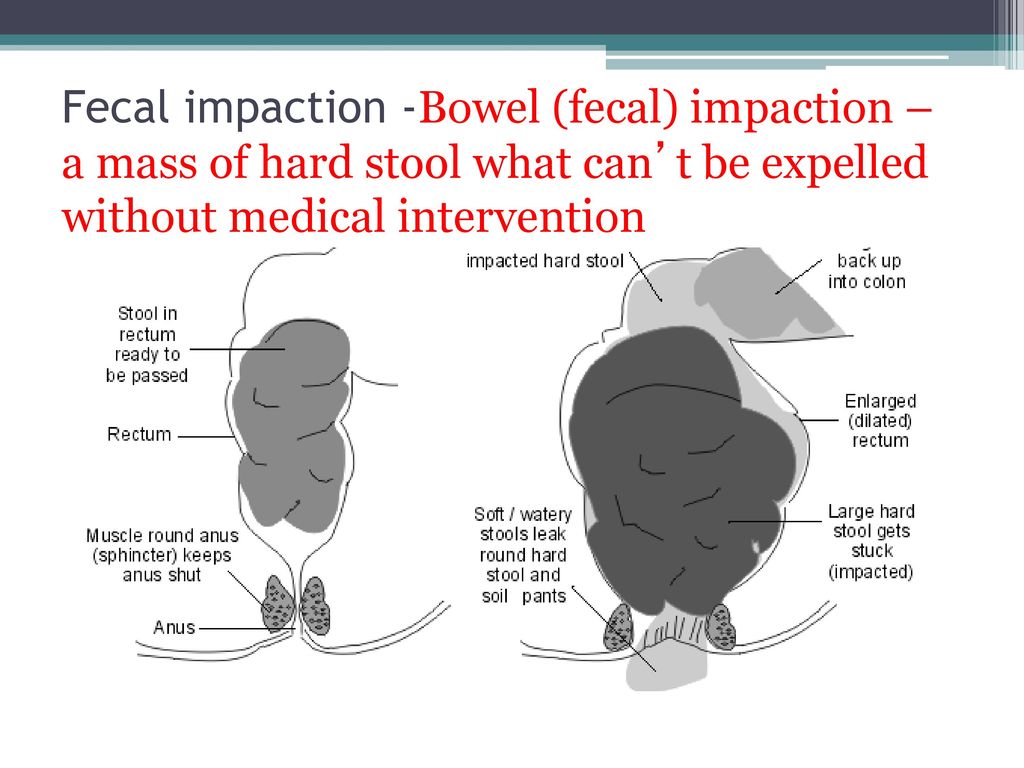

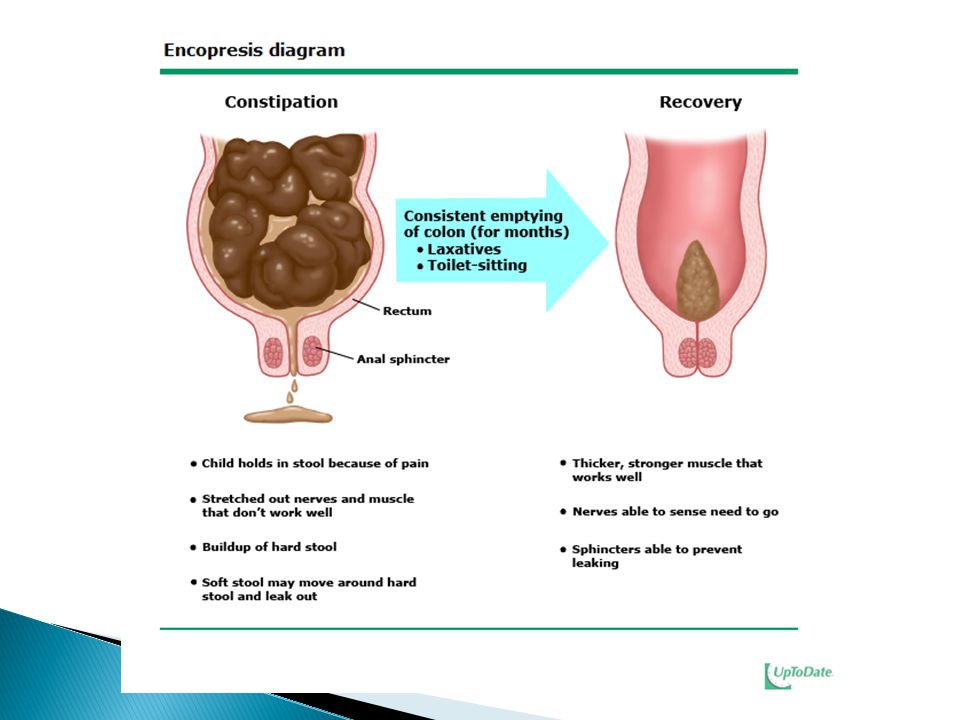

When encopresis occurs, it begins with stool retention in the colon. Many of these youngsters simply may not respond to the urge to defecate and thus withhold their stools. As the intestinal walls and the nerves within them stretch, nerve sensations in the area diminish. Also, the intestines progressively lose their ability to contract and squeeze the stools out of the body. Therefore, these children find it increasingly difficult to have a normal bowel movement. Most of these children are chronically constipated.

Therefore, these children find it increasingly difficult to have a normal bowel movement. Most of these children are chronically constipated.

With time, these retained stools become harder, larger and much more difficult to pass. Bowel movements then can be painful, which further discourages these children from passing the stools.

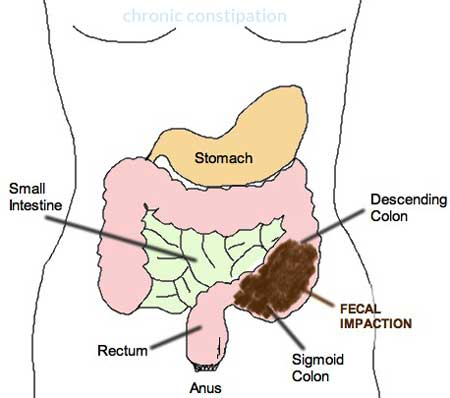

Eventually, the sphincters (the muscular valves that normally keep stools inside the rectum) are no longer able to hold back all the stool. Large, hard feces may be retained in the colon (large intestine) and rectum, but liquid stool can begin to seep around this impacted mass, passing through the anus and staining the underwear. At other times, semiformed or partial bowel movements may pass into the underwear, and because of the decreased sensation, the child may not be aware of it.

Possible causes

Some youngsters are predisposed from birth to early colonic inertia - that is, a tendency toward constipation because their intestinal tracts lack full mobility. Early in life these children might have experienced constipation that required dietary and medical management.

Early in life these children might have experienced constipation that required dietary and medical management.

Some children develop constipation and encopresis because of unsuccessful toilet training as toddlers. They may have fought the toilet training process, been pushed too fast, or were punished for having accidents. Struggling with their parents for control, they may have voluntarily withheld their stools, straining to hold them as long as they could. Some children may actually have had a fear of the toilet, even thinking that they themselves might be flushed away.

A number of other factors can also contribute to the eventual development of encopresis. Sometimes children may have pain when they have a bowel movement due to an infection or a tear near their rectum. Emotional causes can include limited access to a toilet or shyness over its use (at school, for example), or stressful life events (marital discord between parents, moves to a new neighborhood, family physical or mental illnesses or new siblings). While most children with encopresis are also constipated, some are not. These children may refuse to use the toilet and simply have normal bowel movements in their underwear or other inappropriate places. In general, these children are demonstrating their attempts to control some difficult aspects of their lives. Professional help is advisable for these children and their families.

While most children with encopresis are also constipated, some are not. These children may refuse to use the toilet and simply have normal bowel movements in their underwear or other inappropriate places. In general, these children are demonstrating their attempts to control some difficult aspects of their lives. Professional help is advisable for these children and their families.

Many parents are astonished that their child with encopresis may not even be conscious of the odor emanating from the stool in his pants. When this odor is constant, the smelling centers of the brain may become accustomed to it, and thus the child actually is no longer aware of it. As a result, these youngsters often are surprised when a parent or someone else tells them that they have an odor. While the youngster himself may not be bothered by the smell, the people around him may not be sympathetic to his problem.

Psychological effects

Exasperated parents often place great pressure on their child to change this behavior – something the youngster may be incapable of without help from a pediatrician. While family members may have ideas on how to solve the problem, their efforts generally will fail when they do not understand the physiological mechanisms at work.

While family members may have ideas on how to solve the problem, their efforts generally will fail when they do not understand the physiological mechanisms at work.

Encopresis can lead to a struggle within the family. As parents and siblings become increasingly frustrated and angry, family activities may be curtailed or the child with encopresis may be ostracized from them. By this stage, the problem often has become a family preoccupation.

As the child and family fruitlessly battle over the child's bowel control, the conflict may extend to other areas of the child's life. His schoolwork may suffer; his responsibilities and chores around the home may be ignored. He may also become angry, withdrawn, anxious, and depressed, often as a result of being teased and feeling humiliated.

Management of encopresis

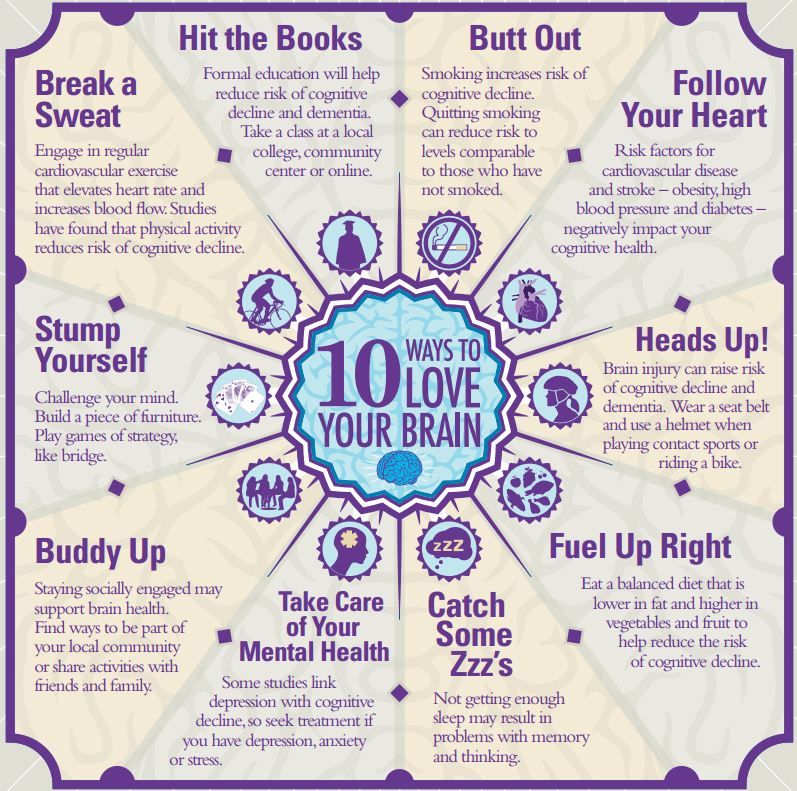

Encopresis is a chronic, complex – but solvable – problem. However, the longer it exists, the more difficult it is to treat. The child should be taught how the bowel works, and that he can strengthen the muscles and nerves that control bowel function. Parents should not blame the child and make him feel guilty, since that contributes to lower self-esteem and makes him feel less competent to solve the problem.

Parents should not blame the child and make him feel guilty, since that contributes to lower self-esteem and makes him feel less competent to solve the problem.

Parents often use a behavior modification or reward system that encourages the child's proper toilet habits. He might receive a star or sticker on a chart for each day he goes without soiling and a special small toy, for example, after a week. This approach works best for a child who truly wishes to solve the problem and is fully cooperative in that effort.

Some youngsters have significant behavioral and emotional difficulties that interfere with the treatment program. Psychological counseling for these children helps them deal with issues like peer conflicts, academic difficulties, and low self-esteem, all of which can contribute to encopresis.

Throughout this treatment process, parents should remind the child that there are other youngsters who have the same problem. In fact, children with the same difficulty probably attend his own school.

Children with encopresis may have occasional relapses and failures during and after treatment; these are actually quite normal, particularly in the early phases. Ultimate success may take months or even years.

One of the most important tasks of parents is to seek early treatment for this problem. Many mothers and fathers feel ashamed and unsupported when their child has encopresis. But parents should not just wait for it to go away. They should consult their doctor and make a persistent effort to solve the problem. If the symptoms are allowed to linger, the child's self-esteem and social confidence may be damaged even more.

Treatment

When encopresis is occurring in a school-age child, a physician experienced in encopresis treatment and interested in working with the child and the family should be involved.

The treatment goals will probably be four fold:

To establish regular bowel habits in the child

To reduce stool retention

To restore normal physiological control over bowel function

To defuse conflicts and reduce concerns within the family brought on by the child's symptoms

To accomplish these goals, attention will be focused not only on the physical basis of encopresis but also on its behavioral and psychological components and consequences.

In the initial phase of medical care, the intestinal tract often has to be cleansed with medications. For the first week or two the child may need enemas, strong laxatives or suppositories to empty the intestinal tract so it can shrink to a more normal size.

The maintenance phase of management involves scheduling regular times to use the toilet in conjunction with daily laxatives like mineral oil or milk of magnesia. Proper diet is important, too, with sufficient fluids and high-fiber foods. These steps will keep the stool soft and prevent constipation. When improperly supervised, these interventions have potential dangers for the health of the child and so should be done only under the supervision of the child's physician. The maintenance phase will usually last two to three months or longer.

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

Treatment Guidelines for Primary Nonretentive Encopresis and Stool Toileting Refusal

BRETT R. KUHN, PH.D., BETHANY A. MARCUS, PH.D., AND SHERYL L. PITNER, M.D., M.P.H.

Nonretentive encopresis refers to inappropriate soiling without evidence of fecal constipation and retention. This form of encopresis accounts for up to 20 percent of all cases. Characteristics include soiling accompanied by daily bowel movements that are normal in size and consistency. An organic cause for nonretentive encopresis is rarely identified. The medical assessment is usually normal, and signs of constipation are noticeably absent. A full developmental and behavioral assessment should be made to establish that the child is ready for intervention to correct encopresis and to identify any barriers to success, particularly disruptive behavior problems. Successful interventions depend on the presence of soft, comfortable bowel movements and addressing toilet refusal behavior. Daily scheduled positive toilet sits are recommended. Incentives may be used to reinforce successful defecation during these sits. A plan for management of stool withholding should be agreed on by the parents/caretakers and the family physician before intervention.

A full developmental and behavioral assessment should be made to establish that the child is ready for intervention to correct encopresis and to identify any barriers to success, particularly disruptive behavior problems. Successful interventions depend on the presence of soft, comfortable bowel movements and addressing toilet refusal behavior. Daily scheduled positive toilet sits are recommended. Incentives may be used to reinforce successful defecation during these sits. A plan for management of stool withholding should be agreed on by the parents/caretakers and the family physician before intervention.

Encopresis affects 1 to 3 percent of children, with higher rates in boys than in girls.1,2 However, encopresis may go undetected unless health professionals directly inquire about toileting habits.3

From 80 to 95 percent of encopresis cases involve fecal constipation and retention. 4 Although several excellent reviews cover retentive encopresis,5–7 encopresis in which fecal retention is not a primary etiologic component is under-represented in the literature. Typically, children with the latter condition soil on a daily basis, with bowel movements of normal size and consistency. Various terms have been used to describe this problem, including functional encopresis, primary nonretentive encopresis and stool toileting refusal. These children may be further divided into at least four subgroups: (1) those who fail to obtain initial bowel training, (2) those who exhibit toilet “phobia,” (3) those who use soiling to “manipulate” their environment and (4) those who have irritable bowel syndrome. Although the toileting dynamics and behavioral characteristics of children with nonretentive encopresis are well described,8–10 few specific treatment guidelines are available for family physicians.

4 Although several excellent reviews cover retentive encopresis,5–7 encopresis in which fecal retention is not a primary etiologic component is under-represented in the literature. Typically, children with the latter condition soil on a daily basis, with bowel movements of normal size and consistency. Various terms have been used to describe this problem, including functional encopresis, primary nonretentive encopresis and stool toileting refusal. These children may be further divided into at least four subgroups: (1) those who fail to obtain initial bowel training, (2) those who exhibit toilet “phobia,” (3) those who use soiling to “manipulate” their environment and (4) those who have irritable bowel syndrome. Although the toileting dynamics and behavioral characteristics of children with nonretentive encopresis are well described,8–10 few specific treatment guidelines are available for family physicians.

While the treatment of retentive encopresis has progressed substantially in the past 20 years, less attention has been paid to the 5 to 20 percent of cases in which constipation is not contributory, or where a child “refuses” the toilet-training process. The family physician is likely to be the first to identify this problem and to provide “front line” intervention. Occasionally, a child presents who is not physically, cognitively or emotionally prepared for toilet training. In these cases, waiting until the child matures is the sensible choice. However, many times the reason is not a lack of readiness skills, but a child who is behaviorally resistant or parents who need information on effective behavior management or toilet-training strategies.11

The family physician is likely to be the first to identify this problem and to provide “front line” intervention. Occasionally, a child presents who is not physically, cognitively or emotionally prepared for toilet training. In these cases, waiting until the child matures is the sensible choice. However, many times the reason is not a lack of readiness skills, but a child who is behaviorally resistant or parents who need information on effective behavior management or toilet-training strategies.11

Once the reason for a child's resistance is identified, specific interventions can be initiated. If the problem is related to a skill deficit (e.g., opening the bathroom door, disrobing, seating self on the toilet, wiping), then modeling, teaching and reinforcement are preferred to passive waiting. In similar fashion, if the child is oppositional or noncompliant with adult instructions, the physician may choose to refer the family to a pediatric psychologist who is familiar with compliance training protocols. In either case, without active intervention, the “strong-willed” child may resist toilet training, create unnecessary stress on the parent-child relationship and increase the risk of abuse.12

In either case, without active intervention, the “strong-willed” child may resist toilet training, create unnecessary stress on the parent-child relationship and increase the risk of abuse.12

This article provides treatment guidelines for children with primary nonretentive encopresis or stool toileting refusal. The guidelines were developed from the literature on toilet training and encopresis, with a special emphasis on practicality and ease of implementation by the family physician. The illustrative case presented on page 2176 shows the efficacy and simplicity of these treatment guidelines.

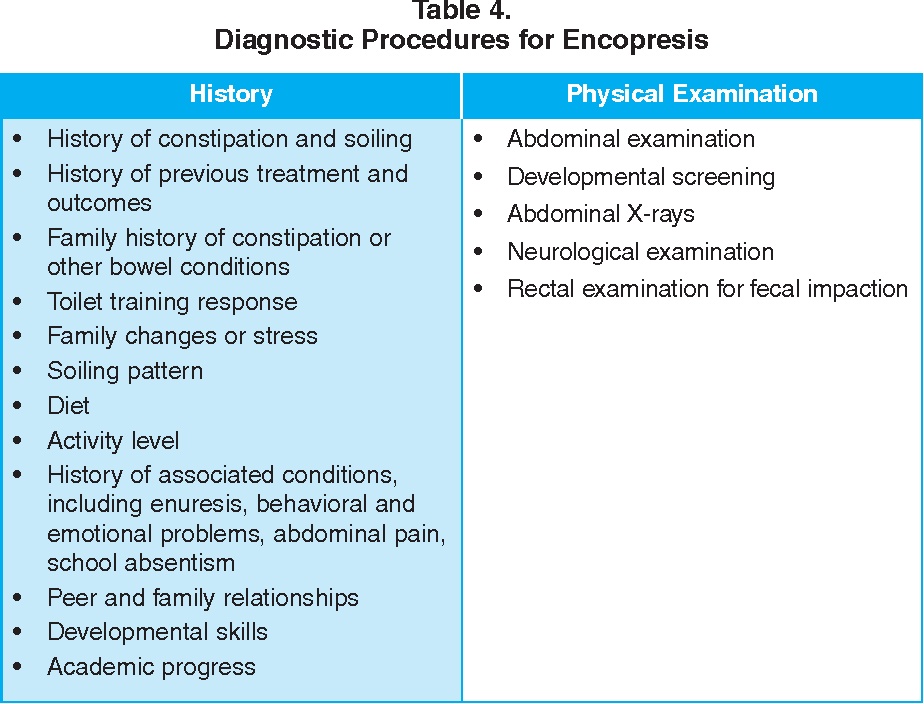

Guideline 1: Identify Potential Medical, Developmental or Behavioral Pathology

MEDICAL

First, a complete physical examination is indicated when a child presents with a history of soiling. The history and physical examination may be the only diagnostic tools necessary to identify retentive encopresis and related organic factors. Few cases of retentive encopresis and even fewer cases of nonretentive encopresis have an organic etiology. 13,14Table 1 summarizes pertinent aspects of the history and physical examination. The principal differential diagnoses of encopresis are listed in Table 2.13–15

13,14Table 1 summarizes pertinent aspects of the history and physical examination. The principal differential diagnoses of encopresis are listed in Table 2.13–15

| History | |

| Stool pattern | |

| Size | |

| Consistency | |

| Interval | |

| History of constipation | |

| Age of onset | |

| History of soiling | |

| Age of onset | |

| Type and amount of material | |

| Diet history | |

| Type and amount of food | |

| Changes in diet | |

| Decrease in appetite | |

| Abdominal pain | |

| Medications | |

| Urinary symptoms | |

| Day or night enuresis | |

| Urinary tract infection | |

| Family history of constipation | |

| Family or personal stressors | |

| Physical examination | |

| Height | |

| Weight | |

| Abdominal examination | |

| Distention | |

| Mass, especially suprapubic | |

| Rectal examination | |

| Sacral dimple | |

| Position of anus | |

| Anal fissures | |

| Anal wink | |

| Sphincter tone | |

| Rectal vault size | |

| Presence or absence of stool in rectum | |

| Pelvic mass | |

| Neurologic examination | |

| Retentive | |

| Functional constipation (95 percent) | |

| Organic (5 percent) | |

| Anal causes | |

| Fissures | |

| Stenosis/atresia with fistula | |

| Anterior displacement of anus | |

| Trauma | |

| Postsurgical repair | |

| Neurogenic causes | |

| Hirschsprung's disease | |

| Chronic intestinal psuedo-obstruction | |

| Spinal cord disorders | |

| Cerebral palsy/hypotonia | |

| Pelvic mass | |

| Neuromuscular disease | |

| Endocrine/metabolic causes | |

| Hypothyroidism | |

| Hypercalcemia | |

| Lead intoxication | |

| Drugs | |

| Codeine | |

| Antacids | |

| Others | |

| Nonretentive | |

| Nonorganic (99 percent) | |

| Organic (1 percent) | |

| Severe ulcerative colitis | |

Acquired spinal cord disease (i. e., sacral lipoma, spinal cord tumor) e., sacral lipoma, spinal cord tumor) | |

| Rectoperineal fistula with imperforate anus | |

| Postsurgical damage to anal sphincter | |

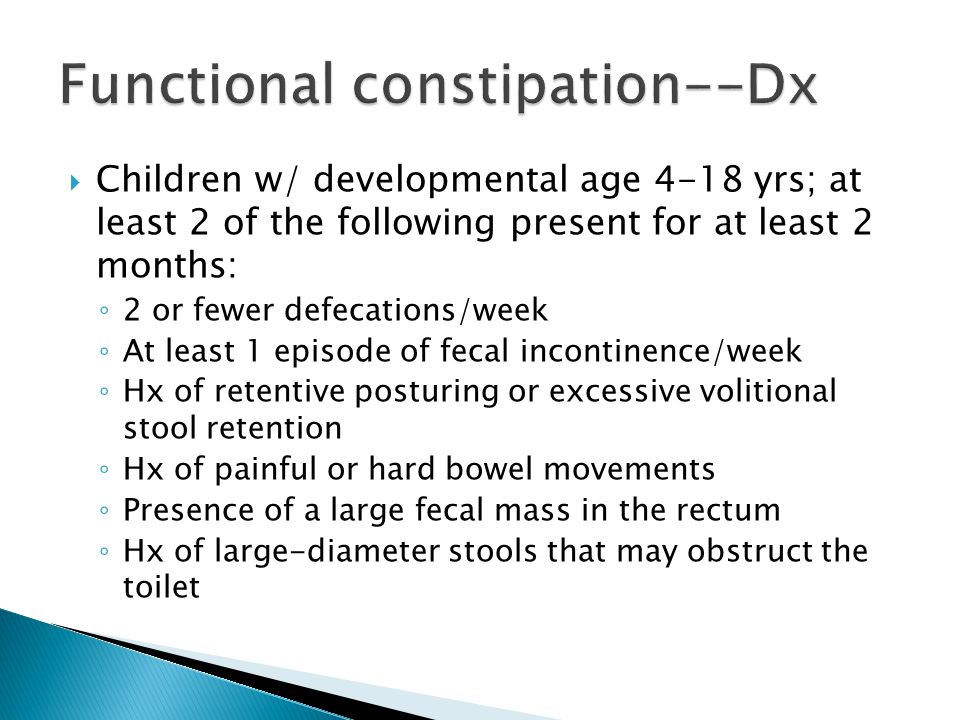

Children with retentive encopresis often soil small quantities of loose fecal matter several times a day but periodically pass very large bowel movements. They may present with urinary complaints and abdominal pain or distention. The physical examination is usually suggestive of constipation.

A consistent soiling pattern characterized by stools that are normal in size and consistency and the absence of constipation usually suggests nonretentive encopresis. If the physician is unable to confirm the presence of constipation or impaction following the history and physical examination, a flat plate radiograph of the abdomen will aid in diagnosis. Further diagnostic investigation using laboratory tests, barium enemas, rectal manometry or biopsy is reserved for use in children who fail conservative therapy or whose history and physical examination suggest an organic etiology. Finally, Hirschsprung's disease is frequently mentioned in the differential diagnosis of encopresis; however, children with Hirschsprung's disease do not typically pass large bowel movements and rarely soil.13

Finally, Hirschsprung's disease is frequently mentioned in the differential diagnosis of encopresis; however, children with Hirschsprung's disease do not typically pass large bowel movements and rarely soil.13

DEVELOPMENTAL

Unrealistic expectations or family priorities (particularly the birth of another child) may prompt parents to begin toilet training before the child is developmentally prepared.16 Physicians can use the 15- or 18-month well baby visit to inquire about plans for toilet training and to ensure that both the child and the family are ready for the process. Initiating training when parents are under time constraints or during periods of family adaptation and stress will be difficult.

Child readiness is determined by the presence of the prerequisite physiologic, developmental and cognitive/psychologic skills to master the complexities of independent toileting. Physiologic readiness is demonstrated by sphincter control, which is usually present by the time the child crawls or walks,17 and by bladder and bowel readiness, shown by the ability to remain dry for several hours at a time and to fully empty the bladder on voiding.

Some children make facial expressions, assume certain body postures (e.g., squatting) or go to a specific location to urinate or defecate. Developmental criteria include attainment of major motor skills such as being able to walk to the bathroom, sit on the toilet, lower and raise pants and flush the toilet. Cognitive/psychologic readiness criteria involve both receptive language adequate to understand toileting-related words such as “wet,” “dry,” “pants” and “bathroom,” and instructional readiness, as indicated by a child who desires to imitate and please parents and to follow simple instructions. Most children meet the above criteria and are ready to be toilet trained between 24 and 30 months of age.16,18

BEHAVIORAL

The most important areas of behavioral assessment of toileting include ruling out the presence of disruptive behavior problems such as aggression, oppositional behavior, noncompliance and temper tantrums, establishing the child's compliance with adult instructions and obtaining a daily diary of toileting habits.

Coexisting behavior problems are a predictor of poor outcome in toilet-training protocols.19 Disruptive behavior and childhood noncompliance across multiple settings (e.g., dressing, bath time, bedtime) require direct attention before toilet training is attempted. It is critical that the child be cooperative and compliant with adult instructions; the child should be able to consistently follow at least seven of 10 parental instructions in a timely manner.

Rather than relying on a parental report, the physician can simply observe the child during an office visit to see if the child complies with parental instructions. Although protocols are available for helping parents decrease a child's oppositional behavior and increase compliance with instructions,20,21 many physicians choose to refer the child to a behavioral psychologist with experience in this area.

Finally, an important component of the behavioral assessment is pretreatment information on daily toileting patterns. A daily toileting diary provides a wealth of information that can be incorporated into the treatment plan (see accompanying patient information handout). For example, the diary may help identify times to schedule toilet sits. Continued use of the diary may provide clues regarding treatment compliance and the effectiveness of the intervention.

A daily toileting diary provides a wealth of information that can be incorporated into the treatment plan (see accompanying patient information handout). For example, the diary may help identify times to schedule toilet sits. Continued use of the diary may provide clues regarding treatment compliance and the effectiveness of the intervention.

Guideline 2: Address Toilet Refusal Behavior

Many children with fecal soiling have a history of painful defecation, toilet “phobia” or toilet refusal behavior.22 Positive toilet sits are one strategy to help children overcome negative associations regarding the bathroom. The goal of positive toilet sits is to associate the bathroom and the toilet with enjoyable activities and parent-child interactions. Initially, sits can be scheduled three to five times daily at the family's convenience. The strategy starts with very short sits (e.g., 30 seconds) that gradually increase to a maximum of five minutes each, using a portable timer to signal completion. The child can remain in underpants or diapers because there is no expectation of producing a bowel movement. While the child is sitting on the toilet, proper foot support, access to enjoyable (relaxing and noncompetitive) activities and individual parental attention should be ensured.

The child can remain in underpants or diapers because there is no expectation of producing a bowel movement. While the child is sitting on the toilet, proper foot support, access to enjoyable (relaxing and noncompetitive) activities and individual parental attention should be ensured.

If a child is extremely resistant to approaching the toilet or potty chair, the parent may employ a gradual shaping procedure. For example, a parent begins by modeling appropriate toileting behavior for a few weeks; after this, the parent starts playing games or reading books with the child in or near the bathroom. The parent and child gradually progress to engaging in these activities while the child is sitting on the potty chair for longer periods of time. During the modeling process, we recommend that fathers and male caretakers sit during urination. Boys should be encouraged to sit while urinating until they are fully bowel trained.

Guideline 3: Ensure Soft, Well-Formed Stools

It is critical to ensure that the child is having relatively frequent, soft and well-formed bowel movements before engaging in any intervention for soiling. Dietary changes or short-term use of supplements such as flavored fiber drinks or bran sprinkles may be needed to increase the number of bowel movements and to maximize daily toileting opportunities.

Dietary changes or short-term use of supplements such as flavored fiber drinks or bran sprinkles may be needed to increase the number of bowel movements and to maximize daily toileting opportunities.

If obtaining frequent, soft and well-formed bowel movements continues to be a problem, the addition of stool softeners or laxatives may be considered. Suitable daily regimens include Milk of Magnesia, in a dosage of 1 to 3 mL per kg per day; mineral oil, in a dosage of 1 to 5 mL per kg per day; or sorbitol, in a dosage of 1 to 3 mL per kg per day. These agents can be given in one or two doses per day. Mineral oil is not indicated in children who are at risk for aspiration.13–15

Any of these supplements may make it more difficult for the child to withhold bowel movements, resulting in more soiling accidents. Consequently, it is a good idea for parents to develop a standard clean-up procedure that can be carried out in a matter-of-fact, emotionally neutral manner. The appropriate reaction is for parents to use a neutral tone of voice while directing the child through developmentally appropriate clean-up activities. Parents should avoid blaming, criticizing or name-calling during this time.

Parents should avoid blaming, criticizing or name-calling during this time.

Guideline 4: Schedule Prompted Toilet Sits

When the child is no longer resistant to sitting on the toilet and is having normal bowel movements, it is time to begin prompted toilet sits during times when the child is likely to defecate. These sits can be scheduled up to five times daily for three to five minutes each. The portable timer, which previously signaled the end of positive sits, now terminates the end of each prompted sit. The best time to schedule prompted sits is five to 20 minutes after each meal—to take advantage of the gastrocolic reflex. Additional sits can be scheduled during high-frequency opportunities as indicated by the daily toileting diary. From the child's perspective, these prompted sits will appear to be no different than the earlier positive sits, as foot support, toys, activities and individual attention are still available. The child's behavior has simply been shaped to the point where he or she can now sit on the toilet without pants or diapers, in a pleasant and relaxed atmosphere, during a time when he or she is likely to defecate.

Once this guideline is satisfied, the family is ready to hold a “graduation ceremony.” This ceremony involves having a small party and informing the child that he or she is now a “big boy” (or girl) and that diapers will no longer be used. It is important that parents do not use diapers occasionally during the day (e.g., on a shopping trip) because that sends a mixed message to the child about toileting expectations.

Guideline 5: Provide Incentives for Appropriate Bowel Movements and Self-Initiation

Although some authors recommend using incentives to target clean pants or diapers,23,24 this practice may encourage fecal withholding and increase the risk of constipation. Incentives can instead be tied to the passage of fecal material in the toilet. Incentives will be most effective if they are age-appropriate, given immediately after the desired behavior is displayed and provided after every occurrence of the behavior during the early phases of teaching.

Many types of incentive programs can be developed, depending on the age of the child, including access to candy, star charts, dot-to-dot pictures, grab bags and special privileges or activities with parents and peers. Selected incentives should be made available only after appropriate toileting, and access to these incentives should be restricted at other times.

Selected incentives should be made available only after appropriate toileting, and access to these incentives should be restricted at other times.

When the child is eliminating in the toilet and no longer having daily soiling accidents, self-initiation skills can be targeted. Parents will want to gradually reduce verbal prompts to use the toilet, train the child to recognize the need to urinate or defecate and teach the child to request to use the bathroom each time. Incentives are now provided any time the child requests access to the bathroom and produces a bowel movement. Young children should inform the parent or caregiver before using the bathroom to ensure proper monitoring and hygiene.

Guideline 6: Arrange for Physician Contact in Case of Stool Withholding

Although ensuring frequent, soft and well-formed bowel movements should reduce the likelihood of a child withholding fecal material, a back-up plan is necessary. For example, the family could be asked to contact the physician if the child withholds for four consecutive days. A daily regimen of dietary supplements or stool softeners, as outlined in Guideline 3, may be all that is needed. If stool withholding leads to impaction, the physician may suggest hypertonic phosphate enemas (one to two per day, for up to three days) or suppositories, both of which work efficiently.14 If parents prefer an oral plan, the physician may use electrolyte solutions or high-dose mineral oil, in a dosage of 15 to 30 mL per year of age per day (maximum: 8 oz). Electrolyte solutions often require inpatient admission and nasogastric tubes to administer the volume and rate needed for effective evacuation. Mineral oil usually takes longer to work than enemas and may result in increased soiling, cramping and abdominal pain until the fecal mass is passed.25 Once the child is no longer impacted, the physician can return to the daily regimen.

A daily regimen of dietary supplements or stool softeners, as outlined in Guideline 3, may be all that is needed. If stool withholding leads to impaction, the physician may suggest hypertonic phosphate enemas (one to two per day, for up to three days) or suppositories, both of which work efficiently.14 If parents prefer an oral plan, the physician may use electrolyte solutions or high-dose mineral oil, in a dosage of 15 to 30 mL per year of age per day (maximum: 8 oz). Electrolyte solutions often require inpatient admission and nasogastric tubes to administer the volume and rate needed for effective evacuation. Mineral oil usually takes longer to work than enemas and may result in increased soiling, cramping and abdominal pain until the fecal mass is passed.25 Once the child is no longer impacted, the physician can return to the daily regimen.

The following illustrative case demonstrates the efficacy of these treatment guidelines in a child with nonretentive encopresis and toileting refusal.

Illustrative Case

A healthy four-year-old boy whose developmental and behavioral histories were unremarkable was brought to the physician because of a 16-month resistance to bowel training. He was generally cooperative with adult requests, exhibited age-appropriate social skills and rarely engaged in temper tantrums or aggressive behavior.

His foster mother reported that he had accomplished daytime bladder training by three years of age, when he began wearing ordinary underpants. He used an adult-sized toilet and stood during urination; however, he had never produced a bowel movement in the toilet. When he needed to defecate, he brought a diaper to his foster mother, stood in front of her and said, “I go poop.” Within one-half hour of being diapered, he would usually walk behind the living room couch to defecate into the diaper. Immediately after defecation, he would return to his foster mother, who would remove the diaper, clean him and put him back into ordinary underpants. The child would defecate only while at home in the living room and only when diapered. In the event of a family outing, arrangements were made to return home to provide him the opportunity to defecate. On occasions when he was refused a diaper, he repeatedly requested a diaper and withheld defecation for up to three days.

The child would defecate only while at home in the living room and only when diapered. In the event of a family outing, arrangements were made to return home to provide him the opportunity to defecate. On occasions when he was refused a diaper, he repeatedly requested a diaper and withheld defecation for up to three days.

A complete history and physical examination revealed no significant medical findings or evidence of fecal impaction. Behavioral assessment included a brief clinical interview, behavior rating scales and a toileting diary that the foster mother maintained throughout assessment and intervention.

The child was placed on a daily fiber supplement to ensure frequent bowel movements and to reduce the likelihood of fecal withholding. The foster mother agreed to contact the physician if the child had not defecated for four days. A program of positive toilet sits was begun, using preferred toys while the foster mother actively engaged him in play and conversation. A kitchen timer was used to signal the end of his “bathroom fun. ”

”

It was reported that he “accidentally” produced his first bowel movement in the toilet during a positive sit. Although he appeared fearful at first, his foster mother reassured him through physical affection, verbal praise and a small reward. By the seventh day, the boy willingly sat on the toilet and was enjoying bathroom activities. During the second week, family and adult friends held a “graduation ceremony,” during which his diapers were symbolically thrown away.

For several days after his graduation, the child repeatedly asked for a diaper. These requests were ignored and the fiber supplements and prompted toilet sits were continued; however, the child did not defecate for three consecutive days. The physician encouraged waiting one more day before beginning oral mineral therapy. The next day, the child defecated during one of his prompted toilet sits.

Over the next few weeks, he continued with the scheduled sits, fiber supplements and incentives for appropriate toileting while his foster mother monitored his toileting habits. By the third week he was no longer soiling his pants and had begun to independently request to use the bathroom. Consequently, the fiber supplements, prompted sits and incentives were gradually discontinued. During a six-month follow-up telephone contact, it was reported that he continued to toilet independently with no soiling accidents (Figure 1).

By the third week he was no longer soiling his pants and had begun to independently request to use the bathroom. Consequently, the fiber supplements, prompted sits and incentives were gradually discontinued. During a six-month follow-up telephone contact, it was reported that he continued to toilet independently with no soiling accidents (Figure 1).

Fecal incontinence (encopresis) in children

We treat children according to the principles of evidence-based medicine: we choose only those diagnostic and treatment methods that have proven their effectiveness. We will never prescribe unnecessary examinations and medicines!

Make an appointment via WhatsApp

Prices Doctors

The first children's clinic of evidence-based medicine in Moscow

No unnecessary examinations and medicines! We will prescribe only what has proven effective and will help your child.

Treatment according to world standards

We treat children with the same quality as in the best medical centers in the world.

The best team of doctors in Fantasy!

Pediatricians and subspecialists Fantasy - highly experienced doctors, members of professional societies. Doctors constantly improve their qualifications, undergo internships abroad.

Ultimate treatment safety

We made pediatric medicine safe! All our staff work according to the most stringent international standards JCI

We have fun, like visiting best friends

Game room, cheerful animator, gifts after the reception. We try to make friends with the child and do everything to make the little patient feel comfortable with us.

You can make an appointment by calling or by filling out the form on the website

Other services of the section "Pediatric proctology"

- Consultation of a pediatric proctologist

- Treatment of constipation and other defecation disorders with botulinum toxin type A in children

Manipulations, procedures, operations

- Stoma care

Frequent calls

- Constipation in a child

- anal fissures

- Blood in baby's stool

- Hemorrhoids in a child

- Papillomas and condylomas of the anus in a child

- Hirschsprung disease

- Gut Management Program

- Bowel dysfunction in children

- Anomalies in the location of the anus

- paraproctitis

Radiography and computed tomography

- Irrigography of the intestine for children

Online payment

Documents online

Online services

Pediatric encopresis: symptoms, causes, treatment This unintentional lack of control causes serious problems, especially in inappropriate places.

Children usually learn to control stools at the age of 4 years. After this age, the child no longer needs aids such as a potty. Organic or other medical causes must be carefully examined before a diagnosis of encopresis is made. Similarly, consideration should be given to whether certain substances the child may have taken, such as laxatives, have any effect.

There are several reasons that may be related to a problem with stool control. Examples of these causes are aganglionic megacolon or a simpler cause such as Hirschsprung's disease associated with peristaltic immobility or insufficiency of lactose digestion.

Constipation and encopresis

It can be said that there are different types of encopresis depending on the category of criteria considered. In this context, two different types can be referred to as encoprese with with lock or encopresis without lock .

Physical examinations and the child's medical history are important in this condition. Because there are different treatments for the two different types of encopresis conditions mentioned above.

Because there are different treatments for the two different types of encopresis conditions mentioned above.

Preserving encopresis (for constipation)

In such cases of encopresis, there is an unusual accumulation of feces. In these cases, examinations and tests are very important. Because this discomfort can be seen with x-ray . Numerous studies show that persistence of encopresis is usually due in part to psychological reasons. Considering all cases of encopresis, it refers to the type of encopresis that saves approximately 80%.

Encopresis without constipation

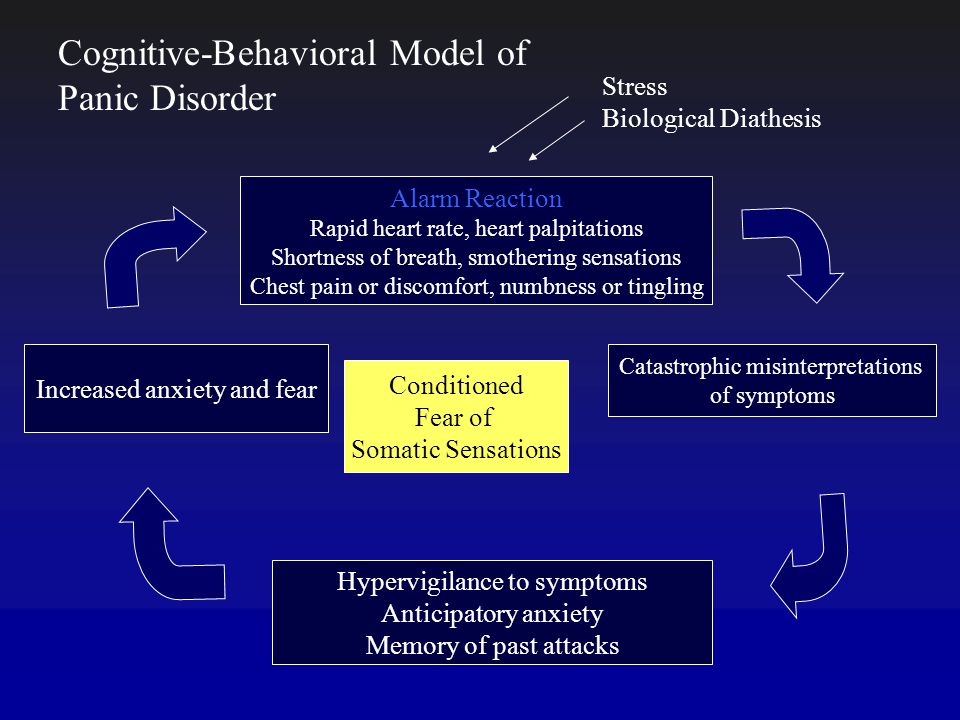

This type of encopresis can be caused by inadequate exercise, environmental and family stress, or opposing behavior patterns. In fact, if a child has problems with encopresis without constipation, other factors that are troubling the child, such as antisocial problems or serious psychological problems, should be evaluated.

Psychiatric evaluation is recommended for complex behavioral, emotional, and even psychotic disorders according to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. For example, a child suffering from depression at an early age and encopresis could result from this situation.

For example, a child suffering from depression at an early age and encopresis could result from this situation.

Primary and secondary encopresis

Another important detail to consider when diagnosing encopresis is whether stool incontinence is permanent or not. Thus, as some children cannot control their stool, while others can overcome this problem within a year. But at the end of this process, the same problem occurs again.

In this context, it is extremely important to make a distinction. Because the causes leading to primary and secondary encopresis may differ from each other. It can be said that this type is mainly based on psychological reasons.

A type that appears later in life, such as high school, and reappears later, although it has been previously studied, may be due to environmental influences, stress at school or home, or some other ailment. Finally, unlike Enuresis Encopresis occurs more frequently during the day than at night. Encopresis in children usually presents in various forms. After the age of four years, encopresis has been found to be more common in boys than in girls. The problem of encopresis in boys aged seven to eight years is 1.5% more than in girls.

Encopresis in children usually presents in various forms. After the age of four years, encopresis has been found to be more common in boys than in girls. The problem of encopresis in boys aged seven to eight years is 1.5% more than in girls.

Due to the nature of this disease and the sensitivity of the subject, it is evident that it is little discussed. However, encopresis has a very serious and powerful effect on children. This disease reduces children's self-confidence and reduces their development in this context. Because, naturally, it should be noted that this disease is very difficult to hide in everyday life.

At the age of encopresis, children mostly go to school. Incontinence of the stool during classes causes serious stress in children. This discomfort, which is also an extremely difficult situation for the family, usually causes anxiety and tension in the family. Although this annoying discomfort - the support that the child will receive from his family during the treatment process, is of great importance. In other words, family members must be prepared to help the child at home.

In other words, family members must be prepared to help the child at home.

Causes of encopresis

Like many diseases, encopresis results from a combination of many different factors. These factors are both physiological and psychological in nature. However, no evidence of a genetic interaction has been found.

Physiological factors may include malnutrition, developmental problems, or inadequate bowel examination . From the point of view of psychological causes, encopresis can be considered as a set of psychological causes, such as the inability to concentrate the child's attention, attention deficit, hyperactivity fear of the toilet or painful urination .

There are various theories that some learning deficiencies play a role in causing this disorder. In this context, failure to internalize the distinctive cues that a child needs to go to the toilet can lead to this process. In other words, when a child wants to go to the toilet, he cannot fully recognize this need and therefore does not go to the toilet.

There are other theories in cases of persistent encopresis called avoidance learning. In such situations, the child learns to hold back the stool to avoid pain or anxiety. In other words, a child who enters a constipation cycle with a negative orientation risks going into secondary encopresis at the end of this process.

Treatment of pediatric encopresis

Medical treatments often include laxatives and enema. It should also be emphasized that a nutrition program that includes high fiber foods and plenty of fluids is also used as a maintenance method. Levin Protocol (1982) appears among the medical treatments carried out to find a solution to this disease. In this method, the aspect of psychological education is especially emphasized (for example, explaining to the child what the colon is with the help of pictures), and in this context, impulses play an important role in the treatment process.

From the point of view of behavioral treatment, methods of solving the problem include making toileting a habit, reorganizing the environment, stimulating the control mechanism, and taking action to identify alternative behaviors.