Lamictal uses depression

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Antidepressant therapy with antidepressants. Lamictal and the problem of drug resistance | Yastrebov D.V.

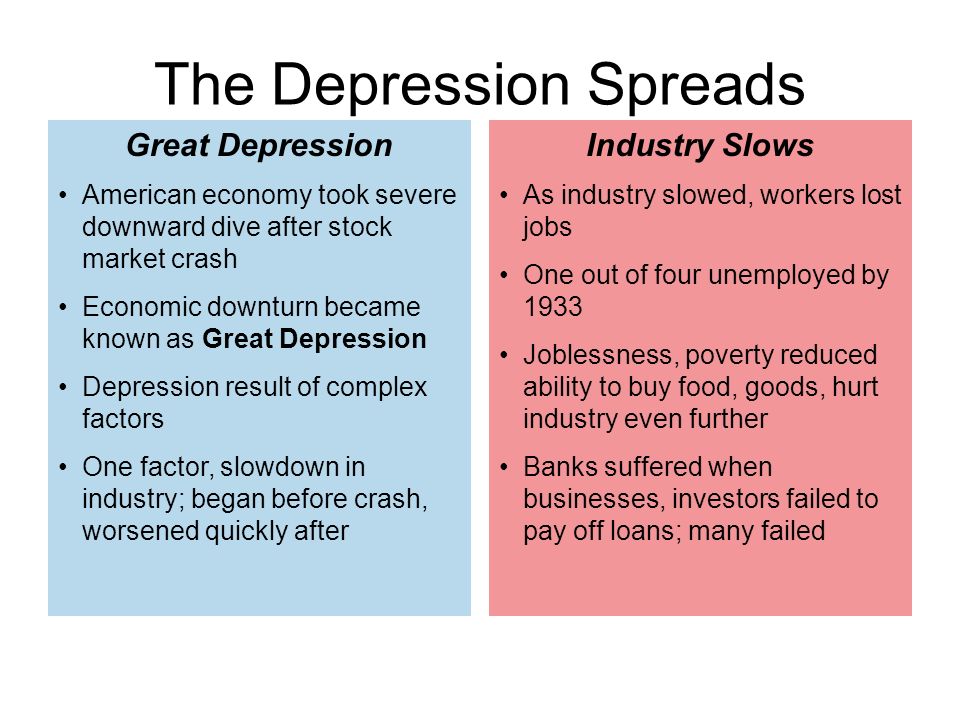

Introduction The initial prescription of antidepressants, the effectiveness of which has been proven in clinical studies, involves achieving a drug response rate of 50-75% within 3-4 weeks of therapy. From this it follows that from 25 to 50% of patients fall into a group of heterogeneous conditions, defined as "treatment-resistant depression" [I.M. Anderson et al., 2000; Schatzberg A.F., 2003]. Today there is no generally accepted definition of the phenomenon of drug resistance. For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

The initial prescription of antidepressants, the effectiveness of which has been proven in clinical studies, involves achieving a drug response rate of 50-75% within 3-4 weeks of therapy. From this it follows that from 25 to 50% of patients fall into a group of heterogeneous conditions, defined as "treatment-resistant depression" [I. M. Anderson et al., 2000; Schatzberg A.F., 2003]. Today there is no generally accepted definition of the phenomenon of drug resistance. For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

M. Anderson et al., 2000; Schatzberg A.F., 2003]. Today there is no generally accepted definition of the phenomenon of drug resistance. For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

Other definitions based on the clinical assessment of the condition suggest an estimate of the number of unsuccessful treatments (2 or more). And finally, the third version of the definitions involves the persistence of depressive symptoms in the absence of success in achieving a state of remission as a result of the therapy (it should be noted that in this case the concepts of remission and drug response are combined) - M. R. Nelsen, D.L. Dunner, 1993; M.E. Thase, P.T. Ninan, 2002.

R. Nelsen, D.L. Dunner, 1993; M.E. Thase, P.T. Ninan, 2002.

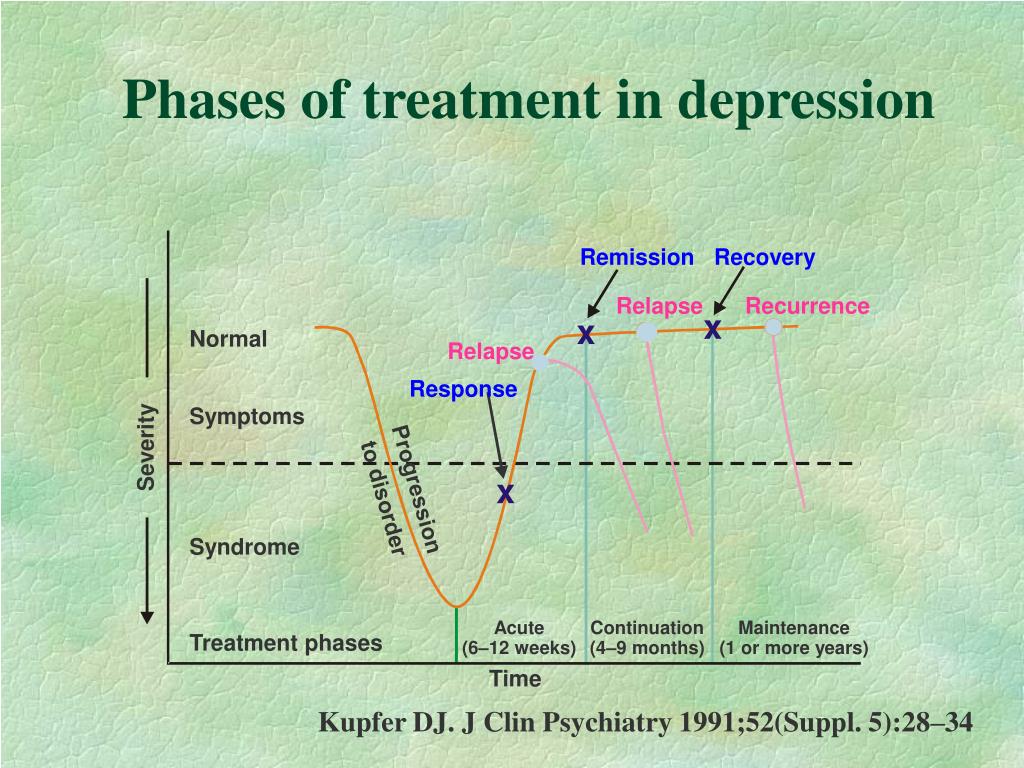

Any of the listed approaches for determining drug resistance is justified only for patients for whom there were no diagnostic inconsistencies and for whom adequate therapy was initially prescribed. In these cases, one speaks of the so-called "true" resistance. However, there are other options in which the achieved drug response against the doctor's expectations can be assessed as insufficient. Among them can be named: an error in the choice of an antidepressant or its dosage; poor tolerance, which makes it impossible to use a specific drug in the appropriate dose, violations of compliance, and a number of others (Fig. 1). It is obvious that in these cases, sometimes defined as "pseudo-resistance" or "relative resistance", medical tactics are fundamentally different and should be aimed at overcoming or eliminating factors that interfere with the achievement of a drug response [H.E. Lehmann, 1974].

After eliminating the signs that allow attributing the lack of a drug response to the account of "pseudo-resistance", the question arises of determining the "true" (absolute) resistance [D. Bird et al., 2002]. In contrast to the previously existing ideas about drug resistance, as a phenomenon of the atomic order, M. Thase and A. Rush (1997) proposed a dynamic multi-stage system for assessing therapy-resistant depression, which is currently widely used. This typology reflects the authors' idea of drug resistance as a stage concept that requires comparison of the entire set of previous therapeutic measures that did not lead to an improvement in the condition (Table 1).

Bird et al., 2002]. In contrast to the previously existing ideas about drug resistance, as a phenomenon of the atomic order, M. Thase and A. Rush (1997) proposed a dynamic multi-stage system for assessing therapy-resistant depression, which is currently widely used. This typology reflects the authors' idea of drug resistance as a stage concept that requires comparison of the entire set of previous therapeutic measures that did not lead to an improvement in the condition (Table 1).

More complex is the taxonomically organized European staged method for assessing drug resistance, partially echoing the approach of M. Thase and A. Rush. Each of the stages of resistance, instead of a serial number, has its own definition with the designation of groups of drugs and the terms of their therapy that did not lead to an improvement in the condition (Table 2).

Variants of depressions,

therapy resistant

The issue of determining the clinical subtype of depression (psychotic, atypical, seasonal) is an important component in the management of this group of patients, since such differences may determine sensitivity to a particular therapy option. In addition, resistance to therapy may be due to an erroneous diagnosis with the definition of a unipolar variant of a depressive disorder in a patient with an undiagnosed bipolar course. Due to the fact that depressive phases in patients with bipolar disorder are clinically detected more often (including due to the greater attendance of patients with depressive symptoms), it is expected that up to half of patients with bipolar disorder can receive treatment according to therapeutic algorithms developed for unipolar depression. [S.N. Ghaemi et al., 1999]. As will be shown below, the question of the correct diagnosis of bipolar disorder is key in the appointment of therapy.

In addition, resistance to therapy may be due to an erroneous diagnosis with the definition of a unipolar variant of a depressive disorder in a patient with an undiagnosed bipolar course. Due to the fact that depressive phases in patients with bipolar disorder are clinically detected more often (including due to the greater attendance of patients with depressive symptoms), it is expected that up to half of patients with bipolar disorder can receive treatment according to therapeutic algorithms developed for unipolar depression. [S.N. Ghaemi et al., 1999]. As will be shown below, the question of the correct diagnosis of bipolar disorder is key in the appointment of therapy.

Coping methods

drug resistance

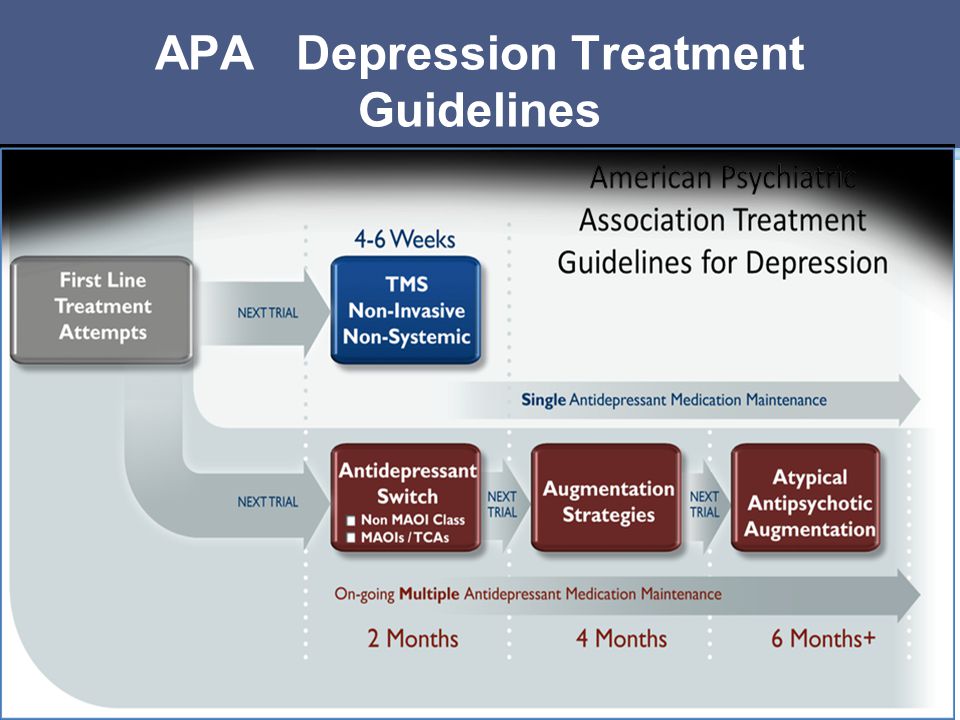

Identification of a case of drug resistance dictates to the doctor the need to change the tactics of managing the patient. At the first stage, the choice is made between two main options: changing the antidepressant or prescribing an additional drug to "enhance" the antidepressant effect of the main drug. Let's take a closer look at each of them.

Let's take a closer look at each of them.

Changing Therapy

Changing the drug is preferable in the event of a complete lack of response to therapy or in the presence of side effects requiring the withdrawal of the originally prescribed antidepressant. Despite the apparent obviousness of the fact that the change of an antidepressant that turned out to be ineffective should imply the choice of a “second-line” drug with a fundamentally different mechanism of action, there are separate data arguing the expediency of switching to a more potent drug of the same group. In particular, for the most commonly prescribed antidepressants - selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), it has been shown that the change of less potent drugs (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram) that did not improve the symptoms of depression to more potent ones (paroxetine, sertraline) gives a percentage of improvements similar to selective ones. serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine) and selective norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (bupropion) up to 30% of cases. At the same time, the number of cases of early discontinuation of therapy due to developed side effects for "double-acting" drugs is 25% higher than for drugs of the SSRI group. Thus, the assumption that the lack of sensitivity of depressive symptoms to the initially prescribed antidepressant indicates the ineffectiveness of the entire class of drugs with a similar mechanism of action has not been confirmed to date [A.J. Rush et al., 2006]. These data, presented in the form of practical recommendations, show that when changing therapy, it is justified to choose a drug not with the largest number of cumulative mechanisms of action, but with the maximum potential in relation to the leading neurotransmitter system (for SSRIs, this is paroxetine (Paxil) and sertraline). At the same time, certain arguments can be given that do not allow defining this tactic as the main one. In particular, an increase in drug potential automatically means a decrease in tolerability. Thus, in patients who notice the occurrence of certain side effects even during first-line therapy, tactics aimed at enhancing the potential of the drug can lead to worse tolerability and a decrease in the level of drug compliance [Thase M.

At the same time, the number of cases of early discontinuation of therapy due to developed side effects for "double-acting" drugs is 25% higher than for drugs of the SSRI group. Thus, the assumption that the lack of sensitivity of depressive symptoms to the initially prescribed antidepressant indicates the ineffectiveness of the entire class of drugs with a similar mechanism of action has not been confirmed to date [A.J. Rush et al., 2006]. These data, presented in the form of practical recommendations, show that when changing therapy, it is justified to choose a drug not with the largest number of cumulative mechanisms of action, but with the maximum potential in relation to the leading neurotransmitter system (for SSRIs, this is paroxetine (Paxil) and sertraline). At the same time, certain arguments can be given that do not allow defining this tactic as the main one. In particular, an increase in drug potential automatically means a decrease in tolerability. Thus, in patients who notice the occurrence of certain side effects even during first-line therapy, tactics aimed at enhancing the potential of the drug can lead to worse tolerability and a decrease in the level of drug compliance [Thase M. E., Rush A.J., 1997].

E., Rush A.J., 1997].

Antidepressant withdrawal policy

Discontinuation of drug antidepressant therapy (AD-therapy) may be accompanied by the occurrence of certain disorders, which are currently accepted to be classified as part of the "anti-adhesion discontinuation syndrome" (AD-AD cessation syndrome).

In earlier studies, the terms “AD withdrawal reaction” and “AD withdrawal syndrome” were more often used to denote pathological symptoms associated with antidepressant (AD) withdrawal [Rotschild, 1995; Dilsaver, 1984; Garner, 1993], which were later changed to emphasize the difference between these disorders and classical withdrawal, which already “reserved” these concepts for itself. However, until now, uncertainty remains in the terminological attribution of the same clinical manifestations, reflecting the opinion of a particular author about the advisability of considering them as withdrawal symptoms [Haddad, 2005].

Early descriptions of SPP AD appeared already in the course of clinical trials of the first ADs (imipramine) [Mann, 1959]. Subsequently, reports of similar disorders were given for almost all groups of AD: other tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), MAO inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and other modern antidepressants [ Hadad, 2004]. It was revealed that the features and severity of SPP BP vary both in relation to different groups of drugs, and for representatives within the same class.

Subsequently, reports of similar disorders were given for almost all groups of AD: other tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), MAO inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and other modern antidepressants [ Hadad, 2004]. It was revealed that the features and severity of SPP BP vary both in relation to different groups of drugs, and for representatives within the same class.

Despite the fact that usually SPP AD manifests itself within a few days after stopping the use of AD or reducing the dosage of the drug and is characterized by a short duration and relative mildness of manifestations, correct recognition if they occur is important, because. these conditions are associated with certain disturbances in daily activities, causing a marked decrease in performance, and their occurrence in a patient unaware of this possibility can lead to serious violations of drug compliance. Also, in some cases, SPP BP can take on a rather pronounced character, requiring hospitalization of the patient [Warner, 2006].

As the main measure to prevent the occurrence of SPP AD or minimize its manifestations, most authors declare the need to follow the prescribed regimen of taking the drug with the elimination of possible interruptions. If it is necessary to cancel blood pressure, it is advisable to follow the method of gradual dose reduction, taking into account the pharmacokinetic properties of a particular drug. The therapeutic value of the last recommendation, in our opinion, however, needs additional verification. According to the data of comparative studies, the gradual abolition of blood pressure allows to achieve an approximately two-fold decrease in the severity of SPP AD compared with one-stage [Van Geffen, 2005]. However, there are other data that show that the gradual withdrawal of the drug rather "blurs" the "rebound" symptoms throughout the entire period of withdrawal. If the manifestations of SPP BP are mild, this technique really makes it possible to additionally “smooth out” them, however, with a greater severity of violations, such tactics of “delaying” may be inappropriate [Yastrebov, 2007]. In addition, the result of gradual withdrawal does not guarantee an asymptomatic outcome of AD withdrawal.

In addition, the result of gradual withdrawal does not guarantee an asymptomatic outcome of AD withdrawal.

According to various sources, up to 50% of patients diagnosed with SPP AD discontinued the drug gradually [Barr, 1994; Pacheco, 169]. Among the factors associated with an increased risk of developing SPP AD, we can name episodes of reactions to the abolition of AD that have already been noted in the anamnesis. In this case, the risk of developing SPP BP increases to 75% [Black, 2000]. For such patients, when canceling AD, gradual withdrawal over 4–8 weeks is desirable, possibly under the “cover” of a short course of replacement therapy, which can be tranquilizers or AD with a different mechanism of action than the drug being withdrawn. These drugs, on the one hand, stop SPP BP, and on the other hand, allow the corresponding receptor subsystems (but not the concentration of the corresponding neurotransmitter) to return to the “pre-therapeutic” state (for example, when paroxetine is canceled - mirtazapine), which in most cases allows you to “cover up” the manifestations reactive symptomatology throughout its course up to complete regression [Warner, 2006].

Combination therapy

In the event that a certain positive shift in the clinical picture of depression is recorded, which, however, indicates only a partial response to therapy, and at the same time the tolerability of the initially prescribed antidepressant is assessed as satisfactory, it is proposed to use combination therapy with the addition of either another antidepressant ("dual therapy"). ”), or a drug of another class that enhances the effect of the main antidepressant (enhanced therapy). There are some differences between these two combination therapy options.

"Dual" therapy involves the addition of a second antidepressant to an existing monotherapy. At the same time, unlike the procedure for changing an antidepressant, its mechanism of action, if possible, should not overlap with that of the “primary” drug. An example is the combination of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram) or a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with a drug such as mirtazapine. However, this tactic has not been widely adopted for a variety of reasons. The main one is that this approach, despite the simplicity of its definition, is largely based on empirical experience and is difficult to rationally evaluate the effectiveness and formalize the assignment algorithm. To date, there are no comparable data on the effectiveness of various combinations of antidepressants; at the same time, the number of side effects, due to which patients stop treatment, increases significantly. Separately, it is necessary to specify the special care required in these cases in the choice of drugs to exclude undesirable drug interactions.

However, this tactic has not been widely adopted for a variety of reasons. The main one is that this approach, despite the simplicity of its definition, is largely based on empirical experience and is difficult to rationally evaluate the effectiveness and formalize the assignment algorithm. To date, there are no comparable data on the effectiveness of various combinations of antidepressants; at the same time, the number of side effects, due to which patients stop treatment, increases significantly. Separately, it is necessary to specify the special care required in these cases in the choice of drugs to exclude undesirable drug interactions.

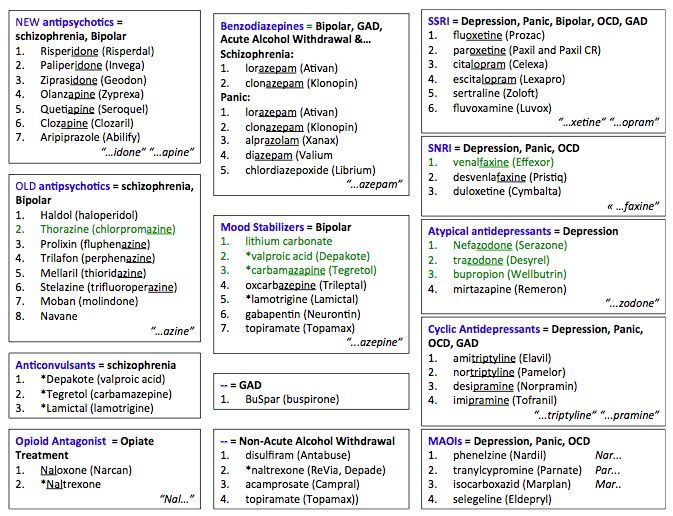

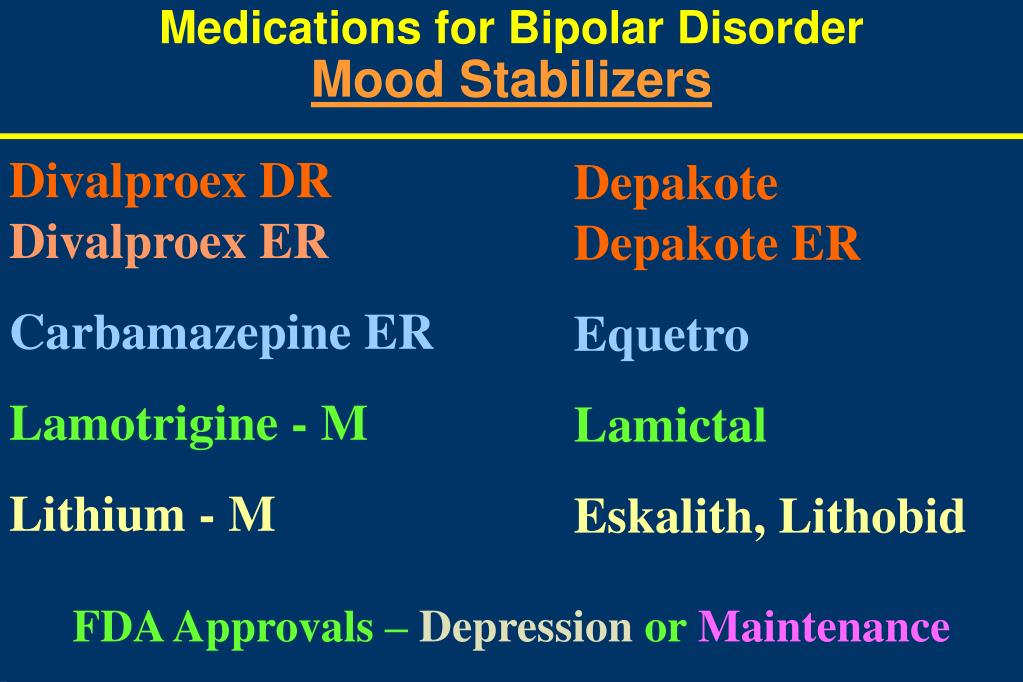

An enhanced version of combination therapy involves the appointment of an antidepressant, coupled with one of the antipsychotics, or with drugs from the group of mood stabilizers. The latter include lithium salts, carbamazepine, salts of valproic acid and lamotrigine (Table 3).

Limitations in the use of antidepressants

The choice of drugs for antidepressant therapy requires mandatory consideration of the characteristics of the clinical picture of an affective disease and its dynamics in general. So, R. El–Mallakh and A. Karippot (2006) indicate that the presence of a history of signs of a bipolar course makes the appointment of antidepressants alone undesirable due to the possibility of affect inversion, cycle acceleration and the appearance of prolonged irritable dysphoria.

So, R. El–Mallakh and A. Karippot (2006) indicate that the presence of a history of signs of a bipolar course makes the appointment of antidepressants alone undesirable due to the possibility of affect inversion, cycle acceleration and the appearance of prolonged irritable dysphoria.

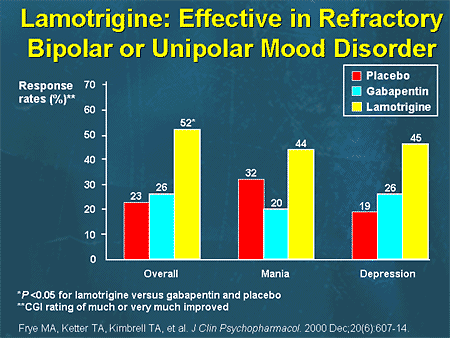

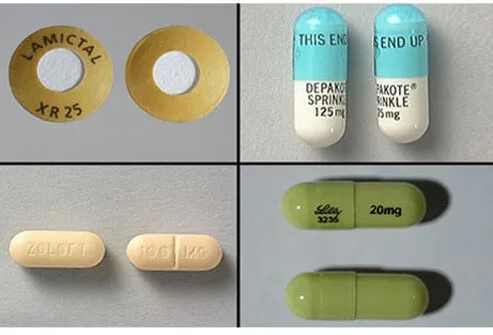

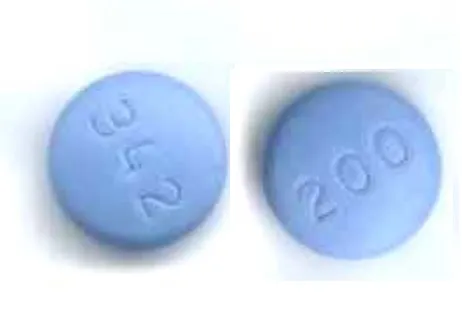

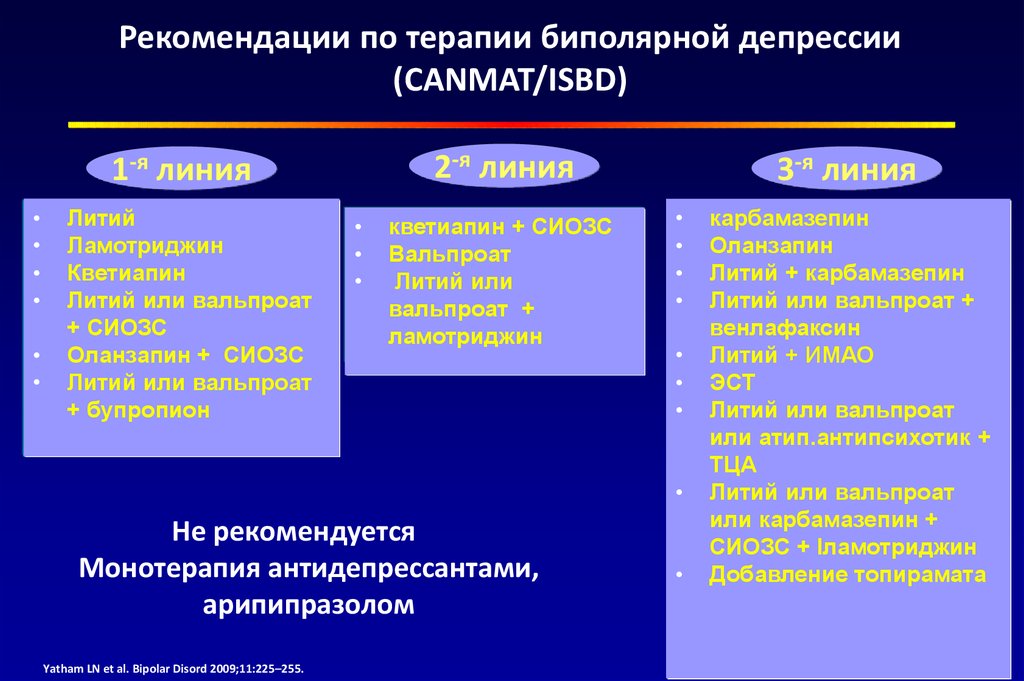

Thus, it is suggested that antidepressant monotherapy is undesirable in patients with depression as part of bipolar disorder due to the possible worsening of the course of bipolar disorder [C.B. Nemeroff, 2001]. Official guidelines published by the American Psychiatric Association [APA Practice Guidelines, 2002] also recommend that antidepressants should not be used as monotherapy in these patients at all initially. Instead, a one-time appointment of at least combination therapy is proposed; it is recommended to use lithium salts or Lamictal (lamotrigine) along with antidepressants as first-line agents at the stage of active therapy. These recommendations are based on recent studies of depression in bipolar disorder defined as resistant to prior therapy (stage II resistance). It has been shown that the appointment of such patients with mood stabilizers (Lamictal (lamotrigine) at doses up to 150-250 mg per day) for combination with antidepressants can significantly increase the level of drug response in comparison with atypical antipsychotics (risperidone) and reduce the likelihood of relapse within a year (with 5% for risperidone to 24% for Lamictal (lamotrigine)) [A. A. Nierenberg et al., 2006].

It has been shown that the appointment of such patients with mood stabilizers (Lamictal (lamotrigine) at doses up to 150-250 mg per day) for combination with antidepressants can significantly increase the level of drug response in comparison with atypical antipsychotics (risperidone) and reduce the likelihood of relapse within a year (with 5% for risperidone to 24% for Lamictal (lamotrigine)) [A. A. Nierenberg et al., 2006].

Separate attention should be paid to the possibility of using drugs that do not belong to the class of antidepressants for monotherapy of depression in bipolar disorder. Existing data confirm the possibility of using some mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics in this capacity (Table 4) [K. Fountoulakis et al., 2007].

It must be noted that the appointment of some of the above drugs for long-term therapy (atypical antipsychotics, especially olanzapine), despite proven effectiveness, may be undesirable due to their inherent undesirable side effects, mainly manifested with long-term use (weight gain, metabolic disorders) .

Long-term prophylactic monotherapy with lamotrigine for bipolar depression

Experience with long-term use of Lamictal has shown that this drug is equally effective in bipolar I and II disorders [Geddes, 2009]. The advantages of Lamictal, which justify its use at the stage of long-term preventive therapy, are: the effect on the residual manifestations of depression, the absence of rebound symptoms upon withdrawal, and the minimal presence of side effects [Calabrese, 2008]. Of particular value to the drug is the absence of the ability to cause weight gain with long-term use, which may justify the need to transfer patients with a tendency to obesity from other drugs (including lithium) to it [Bowden, 2006].

Supplement

Article sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline

1 HAMD: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Literature

1. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159 (April suppl).

Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159 (April suppl).

2. Anderson I. M., Nutt D. J., Deakin J. F. W. Evidence–based guidelines for treating depressive illness with antidepressants: a revision of the 1993 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol (2000), 14, 3–20.

3. Barr L. C., Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H. Physical symptoms associated with paroxetine discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry (1994), 151, 289.

3. Bird D., Haddad P. M., Dursun S. M. An overview of the definition and management of treatment–resistant depression. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni 2002; 12:92–101.

4. Black K., Shea, C., Dursun, S., Kutcher, S. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Psychiatry NeuroSci (2000), 25, 255–261.

5. Calabrese JR, Huffman RF, White RL, Edwards S, Thompson TR, Ascher JA, et al. Lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar depression: results of five double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Bipolar Disord 2008; 10:323–33.

Bipolar Disord 2008; 10:323–33.

6. Charles L. Bowden, M.D. Joseph R. Calabrese, M.D. Terence A. Ketter, M.D. Gary S. Sachs, M.D. Robin L. White, M.S. Thomas R. Thompson, M.D. Impact of Lamotrigine and Lithium on Weight in Obese and Nonobese Patients With Bipolar I Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1199–1201.

7. Dilsaver S. C., Greden, F. J. Antidepressant withdrawal phenomena. Biol Psychiatry (1984), 19, 237–256.

8. Ghaemi S. N., Sachs G. S., Chiou A. M., Pandurangi A. K., Goodwin K. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord 1999;52:135–44.

9. El–Mallakh R. S., Karippot A. Chronic depression in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Aug;163(8):1337–1341; quiz 1478.

10. Fountoulakis K. N., Vieta E., Siamouli M. et al. Treatment of bipolar disorder: a complex treatment for a multi-facet disorder. Annals of General Psychiatry 2007, 6:27 (http://www.annals-general-psychiatry.com/content/6/1/27).

11. Garner E.M., Kelly, M.W., Thompson, D.F. Tricyclic antidepressant withdrawal syndrome. Ann Pharmacother (1993), 27, 1068–1072.

Garner E.M., Kelly, M.W., Thompson, D.F. Tricyclic antidepressant withdrawal syndrome. Ann Pharmacother (1993), 27, 1068–1072.

12. Haddad P.M. Do antidepressants cause dependence? Epidemiologie e Psychiatria Sociale (2005), 14, 58–62.

13. Haddad P. M., Anderson, I., Rosenbaum, J. (2004). Antidepressant discontinuation syndromes. In Haddad P., Dursun, P., Deakin, B. (Ed.), Adverse syndromes and psychiatric drugs: a clinical guide. (pp. 183–205). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

14. John R. Geddes, Joseph R. Calabrese and Guy M. Goodwin. Lamotrigine for treatment of bipolar depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry (2009) 194, 4–9.

15. Lehmann H. E. Therapy–resistant depressions–a clinical classification. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol 1974;7:156–63.

16. Mann A. M., MacPherson, A. Clinical experience with imipramine (G22355) in the treatment of depression. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal (1959), 4, 38–47.

17. Messenheimer J., Mullens E. L., Giorgi L., Young F. Safety of adult clinical trial experience with lamotrigine. Drug Safety 1998, 18: 281–296.

L., Giorgi L., Young F. Safety of adult clinical trial experience with lamotrigine. Drug Safety 1998, 18: 281–296.

18. Nelsen M. R., Dunner D. L. Clinical and differential diagnostic aspects of treatment-resistant depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research. Vol. 29, 1, January–February 1995, 43–50.

19. Nemeroff C. B., Evans D. L., Gyulai L., Sachs G. S., Bowden C. L., Gergel I. P., Oakes R., Pitts C. D.: Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine and paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:906–912

20. Nierenberg A. A., Ostacher M. J., Calabrese J. R., Ketter T. A., Marangell L. B., Miklowitz D. J., Miyahara S., Bauer M. S., Thase M. E., Wisniewski S. R., Sachs G. S. Treatment–resistant bipolar depression: a STEP–BD equipoise randomized effectiveness trial of antidepressant augmentation with lamotrigine, inositol, or risperidone. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;163(2):210–6.

21. Pacheco L., Malo, P., Aragues, E., Etxebeste, M. More cases of paroxetine withdrawal symptoms. Brit J Psychiatry (169), 169, 384.

More cases of paroxetine withdrawal symptoms. Brit J Psychiatry (169), 169, 384.

22. Rotschild A. J. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor–induced sexual dysfunction: efficacy of a drug holiday. Am J Psychiatry (1995), 152, 1514–1516.

23. Rush A. J., Kraemer H. C., Sackeim H. A., et al. Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1841–1853.

24. Rush A. J., Trivedi M. H., Wisniewski S. R., Stewart J. W., Nierenberg A. A., Thase M. E., Ritz L., Biggs M. M., Warden D., Luther J. F., Shores–Wilson K., Niederehe G., Fava M. Bupropion–SR , sertraline, or venlafaxine–XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006 Mar 23;354(12):1231–1242.

25. Santos M. A., Rocha F. L., Hara C. Efficacy and Safety of Antidepressant Augmentation With Lamotrigine in Patients With Treatment–Resistant Depression: A Randomized, Placebo–Controlled, Double–Blind Study. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008; 10(3): 187–190.

2008; 10(3): 187–190.

26. Schatzberg A. F., Cole J. O., DeBattista C. Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2003:42.

27. Souery D., Amsterdam J., de Montigny C., Lecrubier Y., Montgomery S., Lipp O., Racagni G., Zohar J., Mendlewicz J. Treatment resistant depression: methodological overview and operational criteria. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology 1999;9(1–2):83–91.

28. Thase M. E., Rush A. J. When at first you don’t succeed: sequential strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:23–29.

29. Thase M. E., Ninan P. T. New goals in the treatment of depression: moving towards recovery. Psychopharma Bull. 2002;36(Suppl 2):24–35.

30. Van Geffen E.C., Hugtenburg, J.G., Heerdink, E.R., Van Hulten R.P., Egberts, A.C.G. Discontinuation symptoms in users of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in clinical practice: tapering versus abrupt discontinuation. 2005.

2005.

31. Warner C.H., Bobo, W., Warner, C., Reid, S., Rachal., J. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Am Fam Physician (2006), 74(3), 449–456.

32. Yastrebov D.V., Alkeeva–Kostycheva, E.A. Comparison of the results of gradual and simultaneous withdrawal of benzodiazepine tranquilizers taken in therapeutic doses. Russian Psychiatric Journal, No. 1, 2008.

Comparative efficacy of mood stabilizers in the complex therapy of bulimia nervosa

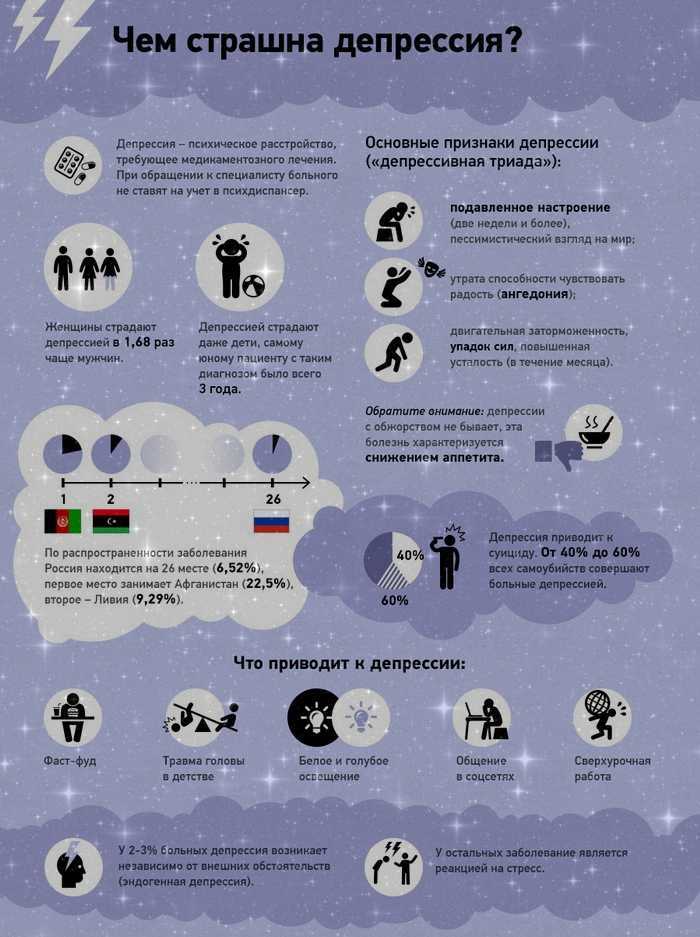

The main forms of eating disorders are anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. There are data in the literature on an increase in the number of patients with this pathology [7-9, 11] during the last decade.

According to ICD-10, for a reliable diagnosis of bulimia nervosa, the following signs are required: a) constant preoccupation with food and an irresistible craving for food, when the patient periodically cannot resist overeating and takes a large amount of food in a short time; b) counteracting the effect of obesity from the food eaten by the patient using one or more methods: inducing vomiting; abuse of laxatives, alternative periods of fasting; use of appetite suppressants, thyroid medications, or diuretics; neglect of insulin therapy by diabetic patients with bulimia; c) the presence in the psychopathological picture of a morbid fear of obesity, when the patient sets for himself a clearly defined limit of body weight - much lower than the premorbid weight, which in the eyes of the doctor represents the optimal or normal weight; frequent history of previous episodes of anorexia nervosa with remissions between the two disorders from several months to several years; the episode preceding bulimia may be symptomatic or mild with moderate weight loss and/or a transient period of amenorrhea.

According to our data [2], patients with bulimia nervosa are characterized by the presence of cyclothymic affective fluctuations, often associated with the season, in combination with increased impulsivity, decreased control over primitive drives and/or severe anxiety disorders, and a tendency to abuse alcohol and drugs and nicotine addiction.

Since affective fluctuations, especially depression, are constantly found in bulimia nervosa, the use of antidepressants and mood stabilizers is justified. The presence of high impulsivity, psychopathic and impulse disorders justify the use of small doses of neuroleptics (behavior correctors). Thus, psychopharmacotherapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa should be complex. We are talking about a combination of antidepressants and normothymic drugs with low doses of antipsychotics. As normotimics, it is advisable to use carbamazepine and lamotrigine.

Lamotrigine is an antiepileptic drug that blocks voltage-gated sodium channels in the presynaptic membranes of neurons and inhibits the excessive release of glutamic acid (an amino acid that plays a key role in the development of epileptic seizures). In addition, effects on calcium channels, GABAergic and serotonergic components are described. It is likely that the complex mechanism of action determines the wide spectrum of activity of lamotrigine in epilepsy and a positive effect on mood, which is used in the treatment of bipolar disorders. It should be noted that to date, lamotrigine is the only normotimic, the effectiveness of which, including in patients with "rapid phase change" [5], has been proven in methodologically correctly constructed blind, placebo-controlled studies [3, 4]. Lamotrigine is particularly effective in preventing depressive phases in patients with bipolar affective disorder [6].

In addition, effects on calcium channels, GABAergic and serotonergic components are described. It is likely that the complex mechanism of action determines the wide spectrum of activity of lamotrigine in epilepsy and a positive effect on mood, which is used in the treatment of bipolar disorders. It should be noted that to date, lamotrigine is the only normotimic, the effectiveness of which, including in patients with "rapid phase change" [5], has been proven in methodologically correctly constructed blind, placebo-controlled studies [3, 4]. Lamotrigine is particularly effective in preventing depressive phases in patients with bipolar affective disorder [6].

Carbamazepine is a derivative of tricyclic iminostilbene containing a carbamoyl group in position 6, which mainly determines the presence of anticonvulsant activity in the drug. Structurally, carbamazepine is close to tricyclic antidepressants of the dibenzoazepine group. The drug has a pronounced anticonvulsant (antiepileptic) and moderately antidepressant (thymoleptic) and normothymic effect. In the mechanism of action of carbamazepine, its GABAergic properties, as well as interaction with central adenosine receptors, play a certain role. In terms of overall effectiveness, carbamazepine is not inferior to lithium carbonate and sodium valproate, however, it has a different spectrum of normothymic action, since its effect is more fully manifested in relation to the reduction of depression compared to mania [1, 12]. The antidepressant effect of carbamazepine is less pronounced than the antimanic effect [10].

In the mechanism of action of carbamazepine, its GABAergic properties, as well as interaction with central adenosine receptors, play a certain role. In terms of overall effectiveness, carbamazepine is not inferior to lithium carbonate and sodium valproate, however, it has a different spectrum of normothymic action, since its effect is more fully manifested in relation to the reduction of depression compared to mania [1, 12]. The antidepressant effect of carbamazepine is less pronounced than the antimanic effect [10].

The aim of this work was to study the effectiveness of mood stabilizers - carbamazepine and lamotrigine in the complex therapy of bulimia nervosa using an antidepressant.

Fluoxetine, a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, was chosen as the first choice antidepressant for bulimia nervosa. Fluoxetine is a weak antagonist of cholinergic, adreno-, and histamine receptors. Unlike many antidepressants, it does not cause a decrease in the functional activity of postsynaptic β-adrenergic receptors, improves mood, reduces feelings of fear and tension, and reduces dysphoria without the effect of sedation. In average therapeutic concentrations, it practically does not affect the functions of the cardiovascular system.

In average therapeutic concentrations, it practically does not affect the functions of the cardiovascular system.

Material and methods

The study included 45 women with various forms of bulimia nervosa. Their mean age was 22.5±4 years; the average duration of the disease is 4.2 years.

Patients included patients (60.9%) with cyclic affective fluctuations in the direction of downward mood and drive disorders and patients with less pronounced cyclic affective fluctuations, characterized by the presence of anxiety, in which there were no or mild drive disorders.

All patients had premorbid cyclothymic personality traits. 28 (62.2%) people abused alcohol, 23 (51%) - narcotic and other psychoactive substances, 72% of patients smoked; 25 (56%) women were distinguished by sexual disinhibition.

All patients at the time of examination had bulimic symptoms (strong hunger, insatiation, bouts of overeating with possible subsequent induction of artificial vomiting). In order to avoid possible, in their opinion, weight gain after overeating, they engaged in intense physical exercise and limited themselves to food, which was expressed in the use of various low-calorie diets, alternative fasting periods, as well as laxatives and diuretics, cleansing enemas. Almost all patients induced vomiting after bouts of overeating.

In order to avoid possible, in their opinion, weight gain after overeating, they engaged in intense physical exercise and limited themselves to food, which was expressed in the use of various low-calorie diets, alternative fasting periods, as well as laxatives and diuretics, cleansing enemas. Almost all patients induced vomiting after bouts of overeating.

Patients were randomized into two groups according to the characteristics of therapy.

In the 1st group (25 patients), patients were prescribed fluoxetine at a dose of 20 mg in the morning and carbamazepine at a dose of 200 mg in 3 doses (50 mg in the morning and afternoon and 100 mg in the evening).

The 2nd group (20 people) was prescribed fluoxetine 20 mg per day in the morning. Lamotrigine was included in therapy according to the scheme: 25 mg per day in the morning and then every 7 days the dose was increased by 25 mg/day up to 100 mg/day.

The selected groups did not differ in age and duration of the disease, as well as the features of complex therapy. In all cases, non-drug methods of treatment were used: individual and group psychotherapy, physiotherapy in the form of a circular shower, ultraviolet therapy, respiratory and relaxation therapeutic exercises.

In all cases, non-drug methods of treatment were used: individual and group psychotherapy, physiotherapy in the form of a circular shower, ultraviolet therapy, respiratory and relaxation therapeutic exercises.

After discharge from the hospital, all patients continued to take fluoxetine and normothymic for 6 months, and then, after fluoxetine was canceled, they continued to take normothymic for prophylactic purposes for another 3 months.

The ranking of bulimic symptoms was carried out as follows: no overeating - 0 points; overeating 1-2 times a week (low level) - 1 point; daily bouts of overeating followed by vomiting, no more than 1 time per day (average level) - 2 points; bouts of overeating daily, several times a day with the use of vomiting and gastric lavage (up to clean water), abuse of laxatives, diuretics (high level) - 3 points.

The severity of depression was determined on the Hamilton scale (HAM-D), the level of reactive and personal anxiety on the Spielberger self-assessment scale, the degree of asthenia according to subjective criteria with a score on a 5-point scale. In addition, memory functions and other cognitive functions were assessed.

In addition, memory functions and other cognitive functions were assessed.

The examination was carried out twice: before the start of pharmacotherapy and after 30 days of inpatient treatment. A year later, a follow-up examination of all patients was carried out.

Results and discussion

Against the background of complex therapy, patients of both groups noted the alignment of mood, a decrease in the frequency and intensity of overeating attacks, vomiting, and the normalization of food intake. As the mood leveled out, the level of fear of weight gain, the intensity of dysmorphophobic experiences, reactive and personal anxiety decreased in most patients.

When quantifying bulimic disorders, the following dynamics was established: before the start of therapy in the 1st group - 2.6 points, after 30 days from the start of therapy - 0.6 points; in the 2nd group before the start of therapy - 2.5 points, after 30 - 0.4 points.

The level of depression according to HAM-D was determined in the 1st group by an indicator of 15-23 points at the beginning of therapy in both groups, and after 30 days 5-7 points in the 1st group and 0-3 points in the 2nd. According to the Spielberger scale, the level of reactive anxiety before the start of therapy in both groups was high - more than 45 points; after 30 days it decreased to 28-35 points in both groups; averaged 29.6 points in the 1st group and 30.1 points in the 2nd. As for personal anxiety, its indicators changed: 34 points before the start of therapy and 28 points after 30 days, without significant differences between groups.

According to the Spielberger scale, the level of reactive anxiety before the start of therapy in both groups was high - more than 45 points; after 30 days it decreased to 28-35 points in both groups; averaged 29.6 points in the 1st group and 30.1 points in the 2nd. As for personal anxiety, its indicators changed: 34 points before the start of therapy and 28 points after 30 days, without significant differences between groups.

The phenomena of asthenia during therapy also decreased: from 5 to 2-3 points in the 1st group and to 0 in the 2nd.

There was also an improvement in cognitive functioning in terms of the ability to memorize and logical construction, the concept of attention, working capacity, the ability to synthesize and analyze the information received.

So, if before the start of the course of treatment, patients memorized from 4 to 6 words spoken aloud and from 3 to 5 geometric figures drawn on paper, then after 30 days of treatment in the 2nd group the number of memorized words increased to 6-9, and geometric shapes - 6-8, in the 1st group the number of memorized words changed little - 5-6 words, and the number of geometric shapes only up to 4-6.

Among the side effects in the 1st group, complaints of drowsiness and lethargy during the day prevailed. In the 2nd group, 3 patients developed skin-allergic reactions in the form of a rash, skin itching. Five patients were excluded from the study: 2 patients from the 1st group due to the severity of side effects and 3 patients from the 2nd group due to allergic reactions.

A follow-up examination of treated patients in a year gave the following results.

In the 1st group, 8 (34.8%) patients were found to be in stable remission, with no clinical manifestations of bulimia (they had no bouts of overeating for 6 months before the examination, body weight corresponded to a BMI from 18 to 21 points), and social rehabilitation (5 patients continued their studies at a higher educational institution, 3 patients got a job, 2 got married). 12 (46.1%) patients reported a relapse of the disease (overeating rate 2 points) after fluoxetine withdrawal, of which only 2 returned to work. In 3 (13%) patients, clinical manifestations persisted while taking medications (the frequency of vomiting ranged from 1 to 3 points).

In 3 (13%) patients, clinical manifestations persisted while taking medications (the frequency of vomiting ranged from 1 to 3 points).

In the 2nd group, 11 (64.7%) patients showed stable remission (for 6 months before the examination, there were no attacks of overeating, body weight corresponded to BMI from 18 to 21 points). At the same time, social rehabilitation was more successful (all 11 patients successfully continued their studies or got a job). 6 (35.2%) patients reported relapse (vomiting frequency 1 to 3 points) after fluoxetine discontinuation, and 1 (5%) patient continued to overeat and vomit.

Thus, the combination of fluoxetine and mood stabilizers during 30-day therapy of patients with bulimia nervosa made it possible to achieve a stable improvement in the condition of patients. At the same time, lamotrigine, compared with carbamazepine, caused a slightly greater decrease in the severity of depression. Carbamazepine had little effect on the cognitive functions studied, while the use of lamotrigine significantly improved them.