Emmy werner resilience theory

How People Learn to Become Resilient

Norman Garmezy, a developmental psychologist and clinician at the University of Minnesota, met thousands of children in his four decades of research. But one boy in particular stuck with him. He was nine years old, with an alcoholic mother and an absent father. Each day, he would arrive at school with the exact same sandwich: two slices of bread with nothing in between. At home, there was no other food available, and no one to make any. Even so, Garmezy would later recall, the boy wanted to make sure that “no one would feel pity for him and no one would know the ineptitude of his mother.” Each day, without fail, he would walk in with a smile on his face and a “bread sandwich” tucked into his bag.

The boy with the bread sandwich was part of a special group of children. He belonged to a cohort of kids—the first of many—whom Garmezy would go on to identify as succeeding, even excelling, despite incredibly difficult circumstances. These were the children who exhibited a trait Garmezy would later identify as “resilience.

” (He is widely credited with being the first to study the concept in an experimental setting.) Over many years, Garmezy would visit schools across the country, focussing on those in economically depressed areas, and follow a standard protocol. He would set up meetings with the principal, along with a school social worker or nurse, and pose the same question: Were there any children whose backgrounds had initially raised red flags—kids who seemed likely to become problem kids—who had instead become, surprisingly, a source of pride? “What I was saying was, ‘Can you identify stressed children who are making it here in your school?’ ” Garmezy said, in a 1999 interview. “There would be a long pause after my inquiry before the answer came. If I had said, ‘Do you have kids in this school who seem to be troubled?,’ there wouldn’t have been a moment’s delay. But to be asked about children who were adaptive and good citizens in the school and making it even though they had come out of very disturbed backgrounds—that was a new sort of inquiry.

That’s the way we began.”

That’s the way we began.”

Resilience presents a challenge for psychologists. Whether you can be said to have it or not largely depends not on any particular psychological test but on the way your life unfolds. If you are lucky enough to never experience any sort of adversity, we won’t know how resilient you are. It’s only when you’re faced with obstacles, stress, and other environmental threats that resilience, or the lack of it, emerges: Do you succumb or do you surmount?

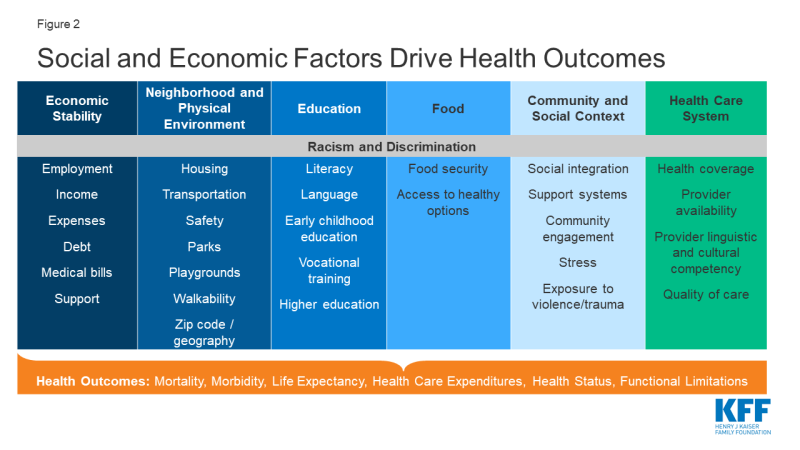

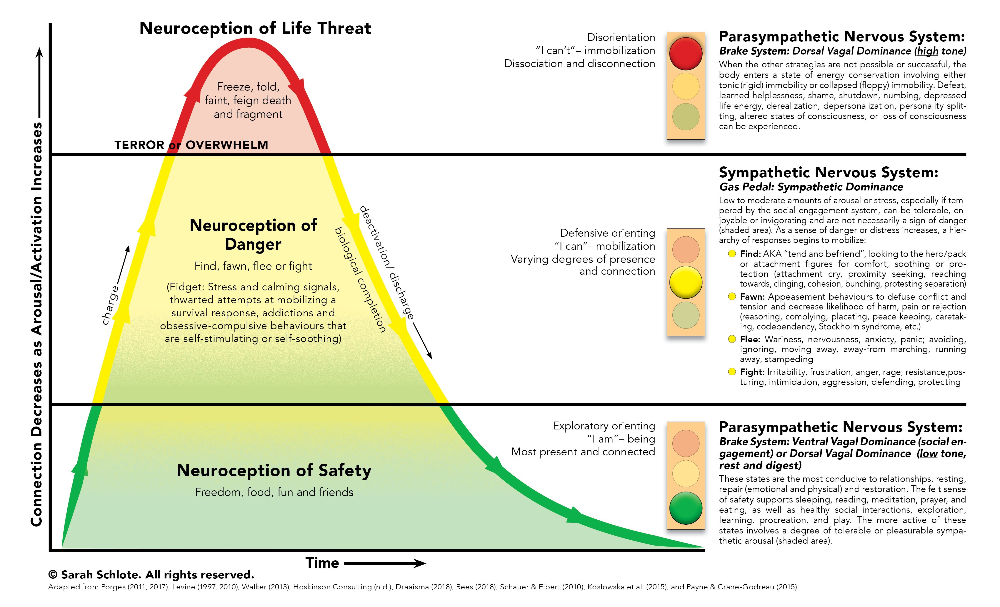

Environmental threats can come in various guises. Some are the result of low socioeconomic status and challenging home conditions. (Those are the threats studied in Garmezy’s work.) Often, such threats—parents with psychological or other problems; exposure to violence or poor treatment; being a child of problematic divorce—are chronic. Other threats are acute: experiencing or witnessing a traumatic violent encounter, for example, or being in an accident. What matters is the intensity and the duration of the stressor. In the case of acute stressors, the intensity is usually high. The stress resulting from chronic adversity, Garmezy wrote, might be lower—but it “exerts repeated and cumulative impact on resources and adaptation and persists for many months and typically considerably longer.”

In the case of acute stressors, the intensity is usually high. The stress resulting from chronic adversity, Garmezy wrote, might be lower—but it “exerts repeated and cumulative impact on resources and adaptation and persists for many months and typically considerably longer.”

Prior to Garmezy’s work on resilience, most research on trauma and negative life events had a reverse focus. Instead of looking at areas of strength, it looked at areas of vulnerability, investigating the experiences that make people susceptible to poor life outcomes (or that lead kids to be “troubled,” as Garmezy put it). Garmezy’s work opened the door to the study of protective factors: the elements of an individual’s background or personality that could enable success despite the challenges they faced. Garmezy retired from research before reaching any definitive conclusions—his career was cut short by early-onset Alzheimer’s—but his students and followers were able to identify elements that fell into two groups: individual, psychological factors and external, environmental factors, or disposition on the one hand and luck on the other.

In 1989 a developmental psychologist named Emmy Werner published the results of a thirty-two-year longitudinal project. She had followed a group of six hundred and ninety-eight children, in Kauai, Hawaii, from before birth through their third decade of life. Along the way, she’d monitored them for any exposure to stress: maternal stress in utero, poverty, problems in the family, and so on. Two-thirds of the children came from backgrounds that were, essentially, stable, successful, and happy; the other third qualified as “at risk.” Like Garmezy, she soon discovered that not all of the at-risk children reacted to stress in the same way. Two-thirds of them “developed serious learning or behavior problems by the age of ten, or had delinquency records, mental health problems, or teen-age pregnancies by the age of eighteen.” But the remaining third developed into “competent, confident, and caring young adults.” They had attained academic, domestic, and social success—and they were always ready to capitalize on new opportunities that arose.

What was it that set the resilient children apart? Because the individuals in her sample had been followed and tested consistently for three decades, Werner had a trove of data at her disposal. She found that several elements predicted resilience. Some elements had to do with luck: a resilient child might have a strong bond with a supportive caregiver, parent, teacher, or other mentor-like figure. But another, quite large set of elements was psychological, and had to do with how the children responded to the environment. From a young age, resilient children tended to “meet the world on their own terms.” They were autonomous and independent, would seek out new experiences, and had a “positive social orientation.” “Though not especially gifted, these children used whatever skills they had effectively,” Werner wrote. Perhaps most importantly, the resilient children had what psychologists call an “internal locus of control”: they believed that they, and not their circumstances, affected their achievements. The resilient children saw themselves as the orchestrators of their own fates. In fact, on a scale that measured locus of control, they scored more than two standard deviations away from the standardization group.

The resilient children saw themselves as the orchestrators of their own fates. In fact, on a scale that measured locus of control, they scored more than two standard deviations away from the standardization group.

Werner also discovered that resilience could change over time. Some resilient children were especially unlucky: they experienced multiple strong stressors at vulnerable points and their resilience evaporated. Resilience, she explained, is like a constant calculation: Which side of the equation weighs more, the resilience or the stressors? The stressors can become so intense that resilience is overwhelmed. Most people, in short, have a breaking point. On the flip side, some people who weren’t resilient when they were little somehow learned the skills of resilience. They were able to overcome adversity later in life and went on to flourish as much as those who’d been resilient the whole way through. This, of course, raises the question of how resilience might be learned.

Teaching Your Child How to Deal with Challenges

We can teach kids to build resilience by providing them with tools to navigate life’s ups and downs throughout their development.

“Resilience” is a buzzword that seemingly everyone uses, but not everyone resonates with it.

For some people, the expectation of being resilient in the face of adversity or trauma can cause emotional harm.

Resilience is not a one-size-fits-all concept. When raising “resilient kids,” resilience is not necessarily a state to strive for. Rather, it’s about teaching kids specific tools and coping strategies to cultivate:

- self-esteem

- self-efficacy

- trust

- kindness

- emotional regulation skills

- adaptability

- healthy relationships

- relationship skills

Every kid has some degree of resilience. Research from 2011 and 2021 suggests that neurobiological processes and genetic underpinnings may help explain why some kids are more naturally “resilient” than others.

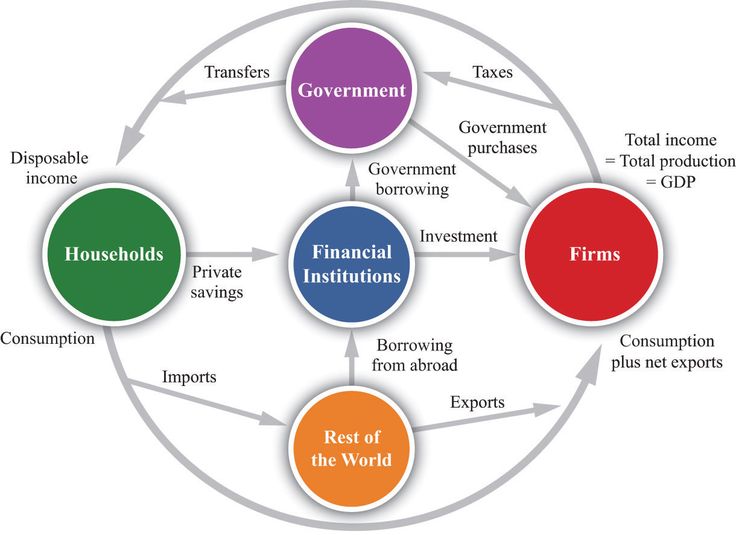

Of course, resilience can’t be fully addressed without factoring in social determinants like systemic racism, socioeconomic status, and mental and physical health, not to mention the clinical implications of an ongoing global pandemic.

Still, there are ways to raise resilient kids by teaching them how to adapt to and recover from the usual ups and downs of young life. Whether you call it “resilience” or not, you can learn what kids need to succeed and thrive throughout their developmental years to achieve mental and physical well-being in adulthood and beyond.

What we don‘t mean by ‘resilient kids’

When we use the word “resilience,” we’re not implying that anyone “should” be resilient in the face of trauma, systemic racism, or adversity. Resilience means different things to different people and can minimize the difficulties experienced by many marginalized communities.

Still, even if your child is sad, disappointed, and angry, there are productive ways they can recognize their emotions and learn to process them.

The definition of resilience has evolved over the years, but most experts agree that resilience can be described as an adaptive response to difficult situations.

Current research defines resilience as the capacity to successfully adapt to challenges. A resilient child, therefore, is one who can bounce back from challenges and setbacks.

A resilient child, therefore, is one who can bounce back from challenges and setbacks.

“A resilient child will take risks and continue to push forward even if they do not initially achieve the goal they desire,” says Elizabeth Lombardo, PhD, a celebrity psychologist based in Chicago.

Why are some children more resilient than others?

Some children may be more naturally resilient, but that doesn’t mean they’re superior to other children or have worked harder to get there. Plus, no matter how much resilience a child has, they can always develop more.

“Resilience is a skill that can be taught,” says Donna Volpitta, EdD, an author and educator at Pathways to Empower based in upstate New York.

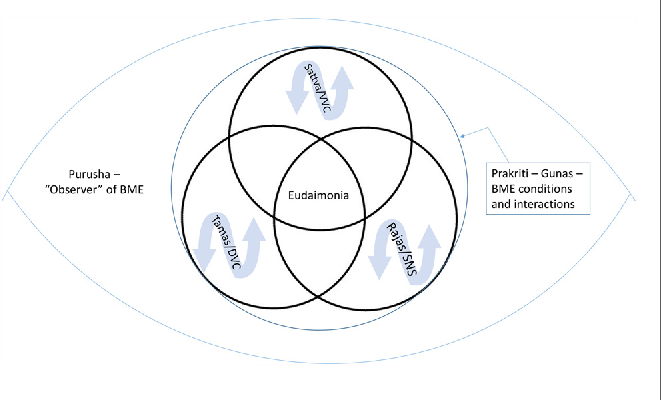

Volpitta, who focuses on the neuroscience of resilience, says that resilience can be determined by the way that we think about the “Four S’s,” as described in her book, “The Four S’s of Resilience”:

- Self. What is the child’s relationship to themself?

- Situation.

Does the child fully understand the circumstances involved?

Does the child fully understand the circumstances involved? - Supports. Who is part of the child’s trusting support system and are they available?

- Strategies. What helps the child work through difficult thoughts and emotions?

“We can use the Four S’s as a framework to help kids prepare for, handle, and reflect on any challenge, and when we do that, we’re proactively building more resilient brain pathways and teaching them to be more resilient,” Volpitta explains.

Everyone experiences the ups and downs of life, but for kids, an unfavorable test score, an embarrassing moment at school, or a breakup with a first love can feel devastating.

When kids develop resiliency, they can more effectively cope with life’s challenges and learn to move forward even when they feel like they’ve failed in some way.

“Children need to face challenges and learn the skills to persevere,” Lombardo says. “That includes managing their stress and inner critic. ”

”

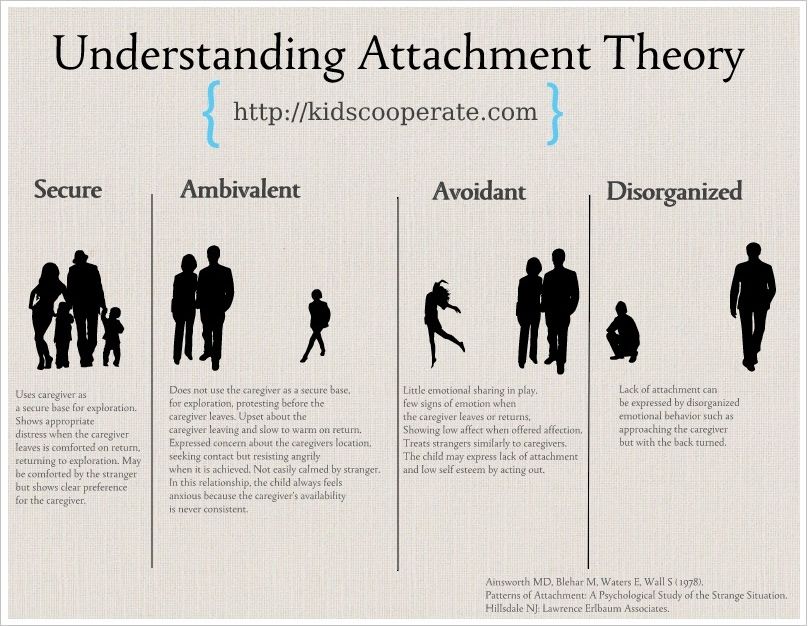

Teaching resilience can start right at home with a trusting adult. In fact, research shows that healthy attachments during childhood promote resiliency.

While many parents feel they have to step in and “save” their children from failure, Lombardo says that it can be more productive to help kids problem-solve how they can improve and adapt to different situations accordingly.

“Highlight values, such as kindness, grit, and empathy by pointing out when your child applies them,” Lombardo says. “Children greatly benefit from living by the notion ‘it’s not failure; it’s data’ to help them be more resilient.”

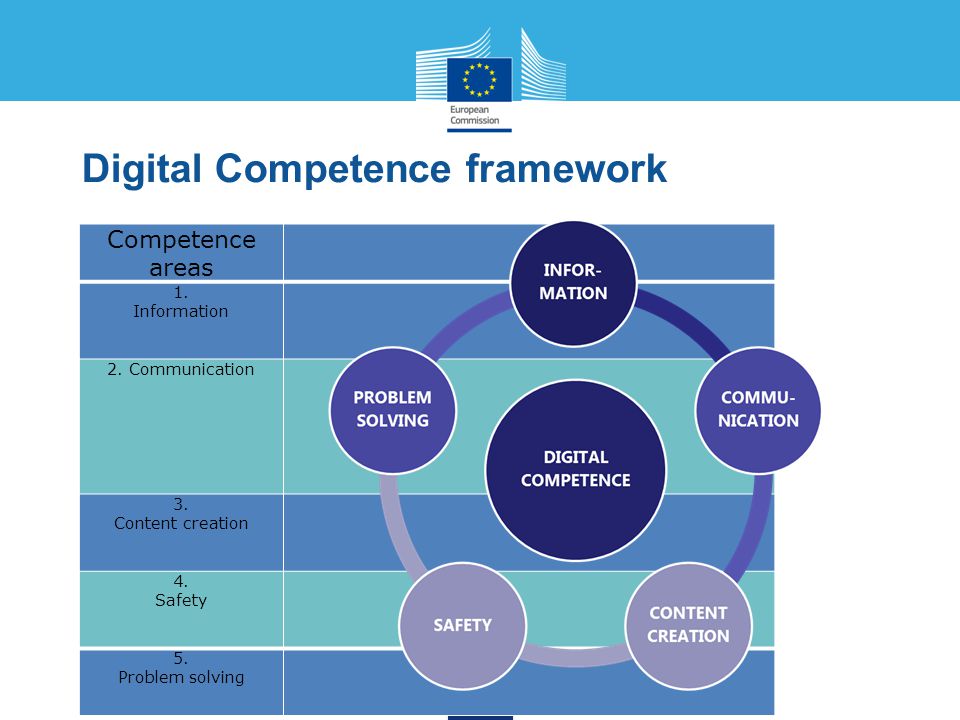

What unique challenges do kids face today?

Today’s children are growing up in front of a digital audience, sharing many intimate aspects of their lives with others in a way that no other generation has done before.

“Children are coming to use digital devices and features such as social media and gaming at an increasingly earlier age, but are not necessarily better prepared for them,” says Teodora Pavkovic, MSc, psychologist, parenting coach, and digital wellness expert at Linewize based in Honolulu.

“The challenges of navigating these made-for-adults virtual spaces are ever-increasing,” she adds.

From navigating mis- and disinformation to cyberbullying, today’s kids face unique circumstances with potentially harmful consequences. “Education around digital wellness, cybersafety, and media literacy is so incredibly important,” says Pavkovic. In addition, children navigating a digital-first world may find it increasingly difficult to develop healthy relationships in real life.

Plus, today’s youth may face unique challenges such as:

- pandemic stress

- climate stress

- racial stress

Teaching kids the building blocks for resilience can potentially help to mitigate their response to trauma, should they experience an adverse event in the future.

Because resilience is a learned skill, there are a few ways you can teach kids to process failure and move on. Kids can build mental elasticity and greater resilience by learning to recognize their emotions and work through them.

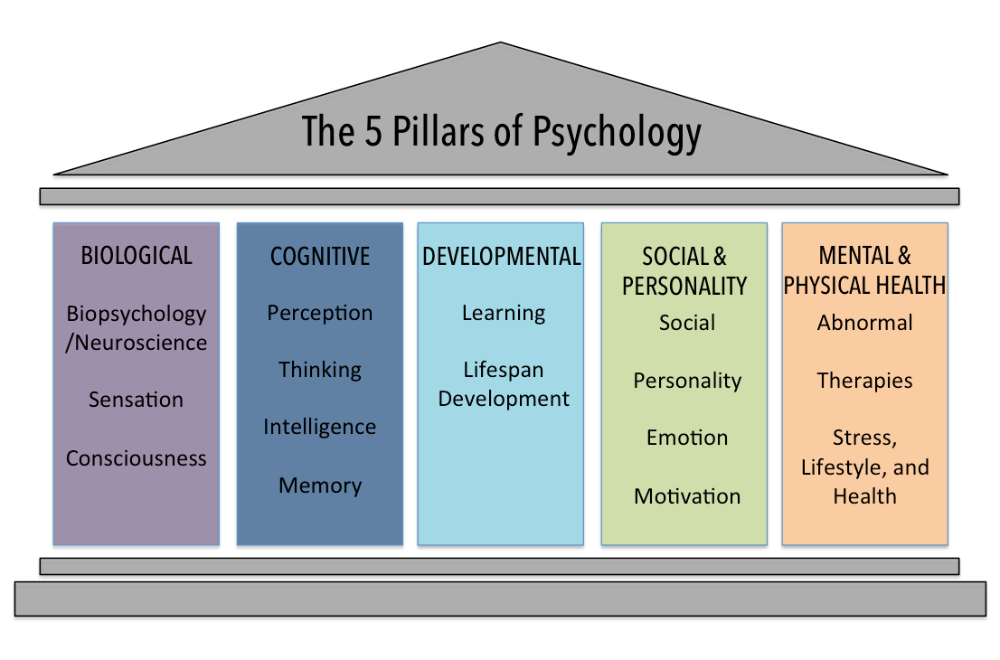

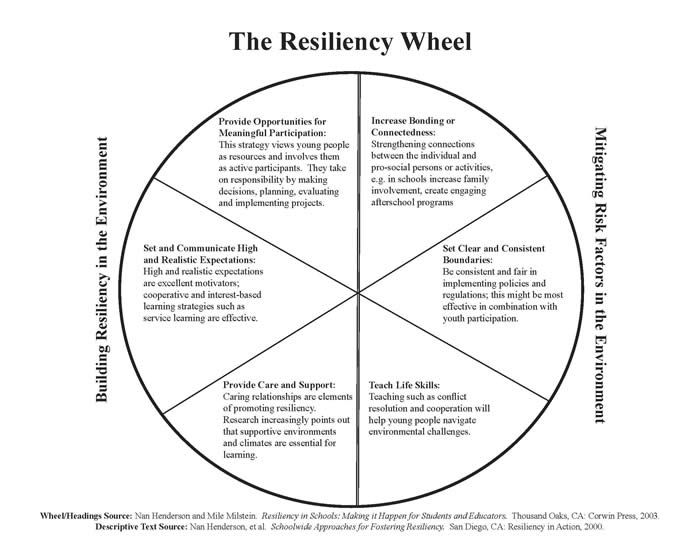

Here, we’ve identified four pillars of resilience for fostering emotional intelligence and resilience in kids.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is your belief in achieving a goal or outcome and is the foundation for developing resiliency.

But self-efficacy can be challenging for some parents since it means relinquishing control and allowing their children the potential for mistakes, disappointment, and failure.

To encourage your child to develop self-efficacy, Pavkovic recommends identifying small, age-appropriate opportunities that allow your child to do and decide things for themselves on their own each day.

According to Lombardo, you could also try helping your child develop moderately difficult, meaningful goals, such as learning a new skill or fundraising for a cause about which your child is passionate.

Self-trust

Self-trust is your ability to rely on yourself and a reflection of your own personal integrity.

To build self-trust in your child, you can start by teaching them how to manage their stress by practicing self-care and the importance of prioritizing their own physical and emotional needs.

“Teaching your children self-care in the digital era is one of the greatest gifts today’s generation of parents can give their kids,” says Pavkovic.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem refers to how you think and feel about yourself.

“Self-esteem will develop as a natural consequence to your child feeling more masterful, and knowing — from direct experience — that even when they make mistakes, they still have the inner resources to handle them,” says Pavkovic.

You can teach your child self-esteem by explaining the importance of clearly communicating their wants and needs respectfully.

Lombardo also recommends highlighting your child’s positive efforts. “Rather than, ‘Good job getting an A on the test,’ reinforce their effort: ‘You worked so hard to study for that test! How does it feel to have your hard work pay off?’ Or, ‘That was very thoughtful to invite the new student to sit with you at lunch!” Lombardo explains.

Kindness

Kindness is your capacity to be aware of others outside of yourself and what you could do to help make their lives a little brighter or easier.

“Kindness is the natural capacity to care about others, one that we are all born with,” says Pavkovic. “Your child has this ability already, but there are always ways of helping them further exercise that muscle.”

Lombardo says you can teach your children about kindness and empathy by encouraging random acts of kindness to a friend or family member or encouraging them to volunteer for a cause that they’re passionate about.

Also, kindness and empathy can help us to forgive ourselves and others. A 2021 study shows that children who better understand the perspectives of others have a larger capacity to forgive.

Once kids have learned how to respond to life’s smaller challenges, they’ve gained the tools to navigate larger challenges, which could help in the face of severe adversity or trauma, to some extent.

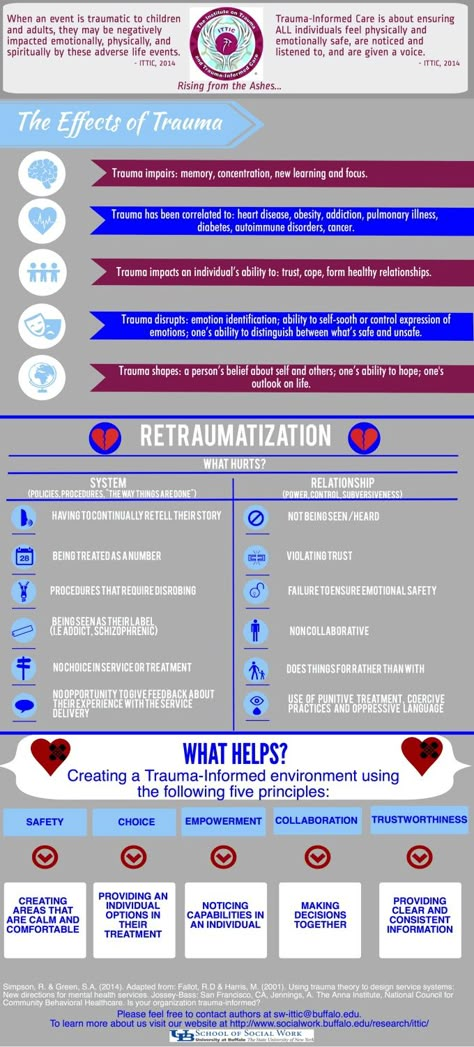

But following a traumatic event, children need more effective coping strategies and professional resources along their road to recovery that go beyond the basic pillars of resilience.

“When we experience trauma, there’s a fundamental way the brain is wired to respond and remember that experience, which will have an effect on the way we experience other similar experiences,” says Volpitta. “When kids experience trauma, they may need treatment to address that.”

When to seek help

If your child has experienced a severe traumatic event, it’s important to seek professional help from a medical or mental health professional.

The tools in this article can help your child overcome basic challenges and help prepare them should they experience trauma in the future. But if your child has already endured a traumatic event, here’s where to seek professional help:

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- American Psychiatric Association

- American Psychological Association

- Center for Parents and Information Resources

- Child Mind Institute

- Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health

- Kids Mental Health Information

- National Institute of Mental Health

Psych Central’s resource hub “Finding a Path Through Trauma” may be helpful as well.

No child should ever feel like they have to be resilient in the face of trauma. Still, strengthening a child from the inside out can help build up their level of resilience should they ever have to face traumatic situations.

Life is full of ups and downs. Try to remind your child that if or when something bad happens at school, in social settings, or online, or if they’ve simply made a mistake, support is available. It’s good to let them know that you’re there to listen and help them adapt to whatever the situation may be.

4 Research by e.Werner and r. Smith

1955 Emmy Werner and Ruth Smith decided to hold group psychological study children born and raised on island Kauai in the Hawaiian archipelago.

During this study Werner and Smith decided to see if they could children and adults cope with stress, if it falls upon them as a result cultural and social upheaval. For this they are from 1955 years began to keep detailed records of all children born on the island: the passage of childbirth, the presence of generic injuries, living conditions (poverty, level of wealth, profession and education parents, overcrowded housing), psychopathology and alcoholism of parents and etc. nine0009

nine0009

All new mothers were interviewed immediately after the birth of the child and year - asked to talk about the characteristic traits, habits and sociability child, about the situation in the family, etc. Children were also tested: as they grow older all children (then teenagers and adults) islands periodically underwent a series of medical and psychological examinations - in 1.5 years old, 10 years old, 18 years old, 32 years old and 40 years old years. Those. The scope of the research is that allow you to trace the life of the islanders for 3 generations now children born at 1955, a long time ago become grandfathers.

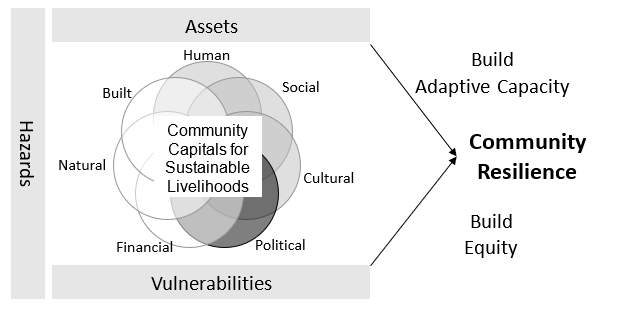

Watching the life of the islanders, Werner and Smith singled out a group of people who from the very beginning of life faced with many difficulties: they have undergone prenatal or birth complications, grew up in dire poverty, their parents were poorly educated abused alcohol or had mental illness, often quarreled among themselves and subjected children to beatings. This was the " group risk ". Such children turned out to be approximately 30% from all subjects . The researchers were sure that such extremely difficult initial conditions, all these children are doomed to poverty, alcoholism, drug addiction. Watching " risk group " yielded astonishing results: approximately a third of the children from the " group risk " encountered in childhood and youth with all conceivable difficulties, nevertheless managed to achieve in a life of success. Authors of such people called " invincible ", and the property of the psyche, which helps to overcome difficulties, called " elasticity psyche ".

This was the " group risk ". Such children turned out to be approximately 30% from all subjects . The researchers were sure that such extremely difficult initial conditions, all these children are doomed to poverty, alcoholism, drug addiction. Watching " risk group " yielded astonishing results: approximately a third of the children from the " group risk " encountered in childhood and youth with all conceivable difficulties, nevertheless managed to achieve in a life of success. Authors of such people called " invincible ", and the property of the psyche, which helps to overcome difficulties, called " elasticity psyche ".

The researchers specifically noted like men with an elastic psyche accept the fact of their paternity. Them not only liked to take care of their children, they believed that raising children is important above all for them own self-improvement. This made them very different from their peers. who consider children a hindrance in their own life. The researchers found another unusual difference. Adults with elastic psyche otherwise communicated with their parents than theirs peers from the "risk group". They have everyone had a difficult relationship with their parents - either due to parental alcoholism or mental illness, or strained relationships in the family. However children with an elastic psyche, growing up, just "disconnected" from the parent problems. This means that parent their problems are more emotional didn't hurt. nine0009

The researchers found another unusual difference. Adults with elastic psyche otherwise communicated with their parents than theirs peers from the "risk group". They have everyone had a difficult relationship with their parents - either due to parental alcoholism or mental illness, or strained relationships in the family. However children with an elastic psyche, growing up, just "disconnected" from the parent problems. This means that parent their problems are more emotional didn't hurt. nine0009

This is an interesting observation because it is generally accepted that emotional "separation" of children from parents is not very good. Gap such an emotional connection perceived as a pathology. However, people with elastic mentality ability get rid of a hectic life parents obviously helped to keep own mental health.

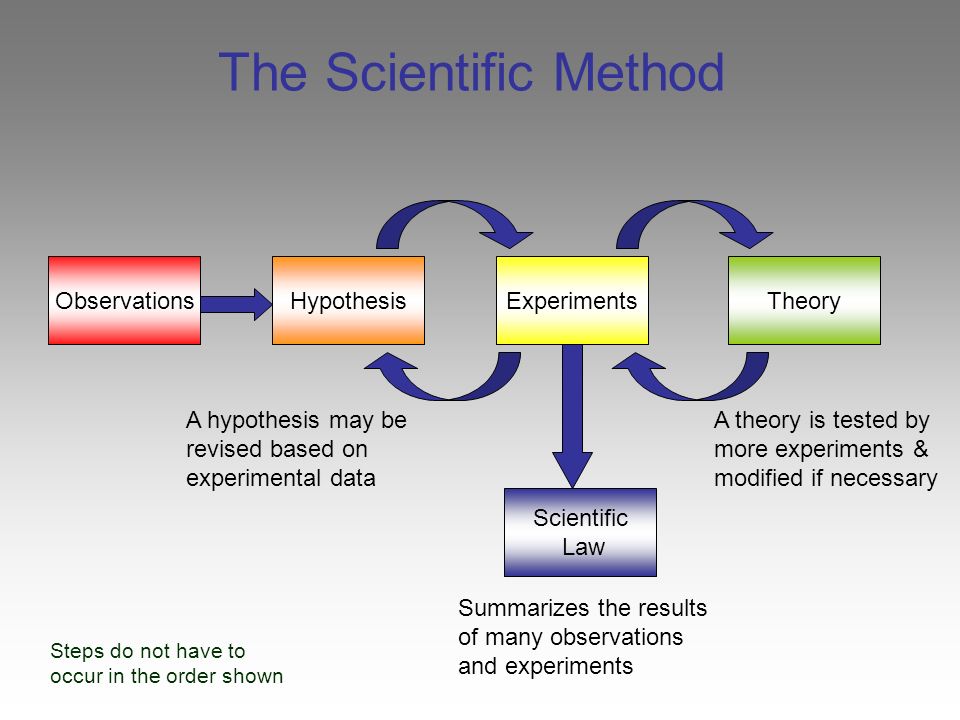

AT in their work, the researchers identified 4 Factors Influencing the Differences Between children at risk who managed to adapt successfully, and those who failed to adapt: active problem solving; ability deal with traumatic circumstances constructively; ability to stimulate positive interaction with others; the ability to accept and see the significance events through faith.

results sustainability studies uncovered influence on the fate of a person close relationships with friends and mentors (coaches, teachers) who supported their undertakings, believed in their potential and encouraged them to strive to achieve life as much as possible. Yes, failure parents (parental alcoholism, mental illness, family violations) did not provide an opportunity children to use the potential of the family, which could be identified and developed, even when the physical parents' condition did not allow them take an active part in fate children. nine0009

Given research served as a starting point to change the view in the aspect of influence family to its members and understanding the characteristics families experiencing a stressful event. Thus, the impact of the family on its members ceases to be perceived as threatening, every member of the family has the potential and strength for recovery and development regardless of the stressful situation.

10 steps to emotional stability

How do people manage to survive psychological trauma? How in situations where some want to lie down and die, others demonstrate amazing resilience? American psychiatrists Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney have been studying people with an inflexible character for 20 years. nine0009

nine0009

They interviewed Vietnamese prisoners of war, special forces instructors, and those who faced serious health problems, violence, and injuries. They collected their discoveries and conclusions in the book Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life's Greatest Challenges.

1. Be optimistic

Yes, the ability to see the bright side supports. Interestingly, in this case we are not talking about "pink glasses". Truly resilient people who have to endure the most difficult situations and still go to the goal (prisoners of war, soldiers of special forces) are able to strike a balance between a positive forecast and a realistic view of things. nine0009

Diehards: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

Realistic optimists take into account the negative information that is relevant to the current problem. However, unlike pessimists, they do not dwell on it. As a rule, they quickly abstract from problems that are currently unsolvable and concentrate all their attention on those that they can solve.

Southwick and Charney were not the only ones to discover this feature. When American journalist and writer Lawrence Gonzalez studied the psychology of survivors of extreme situations, he found the same thing: they balance between positive attitude to the situation and realism. nine0009

The logical question is: how the hell do they do it? Gonzalez realized that the difference between such people is that they are realists, confident in their abilities. They see the world for what it is, but they believe that they are rock stars in it.

2. Look fear in the eye

Neurology says the only real way to deal with fear is to look it in the eye. That's what emotionally stable people do. When we avoid scary things, we become even more afraid. When we face fears face to face, we stop being afraid. nine0009

Diehards: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

To get rid of the memory of fear, you need to experience this fear in a safe environment. And the exposure must be long enough for the brain to form a new connection: in this environment, the stimulus that causes fear is not dangerous.

And the exposure must be long enough for the brain to form a new connection: in this environment, the stimulus that causes fear is not dangerous.

Researchers hypothesize that fear suppression results in increased activity in the prefrontal cortex and inhibition of fear responses in the amygdala. nine0009

This method has proven effective in the treatment of anxiety disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder and phobias. Its essence is that the patient is forced to face fear face to face.

Medic and Special Forces Instructor Mark Hickey believes that facing fears helps to recognize them, keeps them in good shape, develops courage, enhances self-esteem and control over the situation. When Hickey is scared, he thinks, "I'm scared, but this test will make me stronger." nine0009

3. Adjust your moral compass

Southwick and Charney found that emotionally stable people have a highly developed sense of right and wrong. Even when in a life-threatening situation, they were always thinking about others, not just about themselves.

The Unbending: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

During the interview, we realized that many resilient individuals had a keen sense of right and wrong, which strengthened them during times of great stress and when they were coming back to life after shocks. Selflessness, caring for others, helping without expecting a reciprocal benefit for oneself - these qualities are often the core of the value system of such people. nine0009

4. Turn to spiritual practices

The main feature that unites people who were able to survive the tragedy.

The Unbending: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

Dr. Amad discovered that religious faith is the very powerful force by which survivors explain both the tragedy itself and their survival.

But what if you're not religious? No problems.

The positive effect of religious activity is that you become part of a community. So you don't have to do anything you don't believe in, you just have to be part of a group that builds your resilience. nine0009

So you don't have to do anything you don't believe in, you just have to be part of a group that builds your resilience. nine0009

Diehards: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

The connection between religion and perseverance can be partly explained by the social aspects of religious life. The word "religion" comes from the Latin religare - "to bind". People who regularly attend religious services gain access to a deeper form of social support than is available in a secular society.

5. Know how to give and receive social support

Even if you are not part of a religious or other community, friends and family can support you. When Admiral Robert Shamaker was captured in Vietnam, he was isolated from other captives. How did he keep his composure? Knocked on the cell wall. The prisoners in the next cell knocked back. Ridiculously simple, but it was these tappings that reminded them that they were not alone in their suffering.

The Unbending: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney. nine0009

During his 8 years in prisons in North Vietnam, Shamaker used his sharp mind and creativity to develop a unique method of tapping communication known as the Tap Code. This was a turning point, thanks to which dozens of prisoners were able to contact each other and survive.

Our brain needs social support to function optimally. During communication with others, oxytocin is released, which calms the mind and reduces stress levels. nine0009

Diehards: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

Oxytocin reduces amygdala activity, which explains why peer support reduces stress.

And it is necessary not only to receive help from others, but also to provide it. Dale Carnegie said, "You can make more friends in two months than you can in two years if you are interested in people and not trying to interest them in you. " nine0009

" nine0009

However, we cannot always be surrounded by loved ones. What to do in this case?

6. Emulate strong personalities

What keeps children growing up in miserable conditions but continuing to lead normal, fulfilling lives? They have role models who set a positive example and support them.

The Unbending: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

Emmy Werner, one of the first psychologists who studied resilience, observed the lives of children who grew up in poverty, in dysfunctional families where at least one of the parents was an alcoholic, mentally ill or prone to violence.

Werner found that emotionally stable children who became productive, emotionally healthy adults had at least one person in their lives who really supported them and was a role model.

Our study found a similar connection: many of the people we interviewed said they had a role model—a person whose beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors inspire them. nine0009

nine0009

Sometimes it is difficult to find someone you would like to be like among your acquaintances. This is fine. Southwick and Charney found that it's often enough to have a negative example in front of you—a person you don't want to be like in any way.

7. Keep fit

Again and again, Southwick and Charney found that the most emotionally stable people had the habit of keeping their body and mind in good shape.

Resilient: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

Many of the people we spoke to were regular exercisers and felt that being physically fit helped them through tough times and during recovery from injury. Some even saved their lives.

Interestingly, maintaining physical fitness is more important for emotionally more fragile people. Why?

Because the stress of exercise helps us adapt to the stress we will experience when life challenges us. nine0009

Diehards: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

Researchers believe that during active aerobic training, a person is forced to experience the same symptoms that appear in moments of fear or excitement: rapid heartbeat and breathing, sweating. After some time, a person who continues to exercise intensively can get used to the fact that these symptoms are not dangerous, and the intensity of fear caused by them will gradually decrease. nine0009

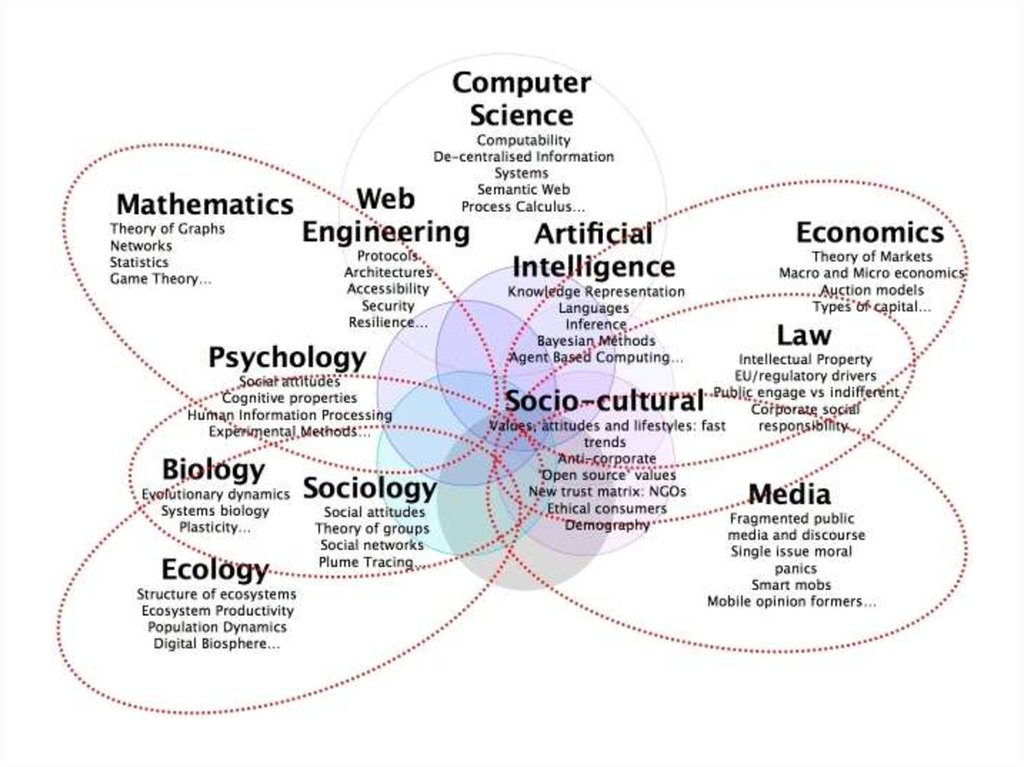

8. Train your mind

No, we are not asking you to play a couple of logic games on your phone. Resilient people learn throughout their lives, constantly enrich their minds, strive to adapt to new information about the world around them.

The Unbending: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

In our experience, resilient people are constantly looking for opportunities to maintain and develop their mental abilities. nine0009

By the way, in addition to stamina, the development of the mind has many more advantages.

The Unbending: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

Cathy Hammond, in her 2004 study at the University of London, concluded that continuous learning has a complex positive effect on mental health: good health, the ability to recover from psychological trauma, the ability to cope with stress, a developed sense of self-worth and self-sufficiency and much more. Continuous learning has developed these qualities through pushing boundaries, a process that is central to learning. nine0009

9. Develop cognitive flexibility

Each of us has a way in which we usually deal with difficult situations. But the most emotionally resilient people are distinguished by the fact that they use several ways to cope with difficulties.

The Unbending: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

Resilient people tend to be flexible—seeing problems from different perspectives and responding to stress in different ways. They do not stick to just one method of dealing with difficulties. Instead, they switch from one survival strategy to another depending on the circumstances. nine0009

They do not stick to just one method of dealing with difficulties. Instead, they switch from one survival strategy to another depending on the circumstances. nine0009

What is the surest way to overcome difficulties that definitely works? Be tough? No. Ignore what's going on? No. Everyone mentioned humor.

The Unbending: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

There is evidence that humor can help people overcome difficulties. Studies in combat veterans, cancer patients, and surgical survivors have shown that humor reduces stress and is associated with resilience and the ability to tolerate stress. nine0009

10. Find the meaning of life

Resilient people don't have a job - they have a calling. They have a mission and purpose that give meaning to everything they do. And in difficult times, this goal pushes them forward.

The Unbending: The Science of Withstanding Life's Challenges

Quoted from Stephen Southwick and Dennis Charney.

According to the Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl's theory that work is one of the pillars of the meaning of life, the ability to see your calling in your work increases emotional stability. This is true even for people doing low-skilled jobs (such as cleaners in a hospital) and for people who fail to do their chosen job. nine0009

Summary: What can help build emotional resilience

- Be optimistic. Do not deny reality, look at the world clearly, but believe in your abilities.

- Look fear in the eye. By hiding from fear, you make the situation worse. Look him in the face and you can step over him.

- Adjust your moral compass. A developed sense of right and wrong tells us what to do and pushes us forward, even when our strength is running out. nine0217

- Be part of a group that believes strongly in something.

- Give and receive social support: even tapping on the cell wall is supported.

- Try to be a role model or, on the contrary, keep in mind the person you do not want to become.

- Exercise: physical activity adapts the body to stress.

- Learn all your life: your mind must be in good shape to come up with the right solutions when you need them. nine0217

- Cope with difficulties in different ways and remember to laugh even in the worst situations.

- Fill life with meaning: you must have a calling and a purpose.

We often hear about post-traumatic mental disorders, but rarely about post-traumatic development. But it is. Many people who have been able to overcome difficulties become stronger.

“The path to prosperity. A New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being”

Quote from Martin Seligman's book. nine0009

Within a month, 1,700 people who survived at least one of these nightmarish events passed our tests. To our surprise, people who experienced one terrible event were stronger (and therefore more prosperous) than those who did not experience any. Those who had to endure two difficult events were stronger than those who had one.