Diagnosis of ptsd in children

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Children

Español (Spanish)

All children may experience very stressful events that affect how they think and feel. Most of the time, children recover quickly and well. However, sometimes children who experience severe stress, such as from an injury, from the death or threatened death of a close family member or friend, or from violence, will be affected long-term. The child could experience this trauma directly or could witness it happening to someone else. When children develop long term symptoms (longer than one month) from such stress, which are upsetting or interfere with their relationships and activities, they may be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

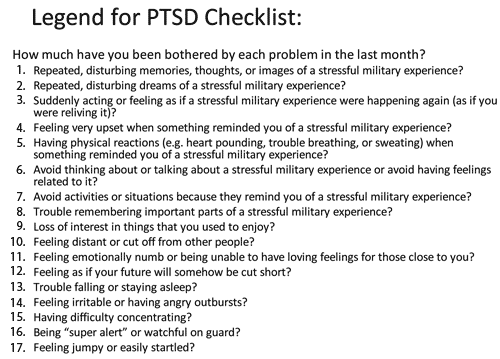

Examples of PTSD symptoms include

- Reliving the event over and over in thought or in play

- Nightmares and sleep problems

- Becoming very upset when something causes memories of the event

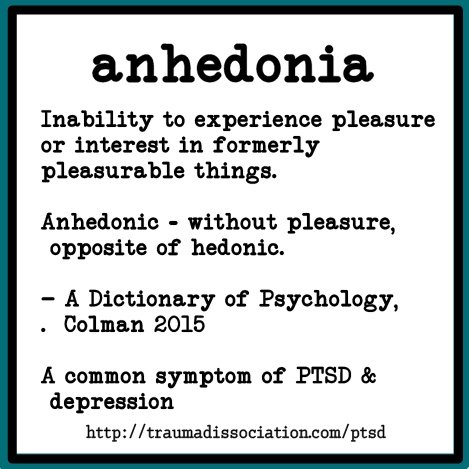

- Lack of positive emotions

- Intense ongoing fear or sadness

- Irritability and angry outbursts

- Constantly looking for possible threats, being easily startled

- Acting helpless, hopeless or withdrawn

- Denying that the event happened or feeling numb

- Avoiding places or people associated with the event

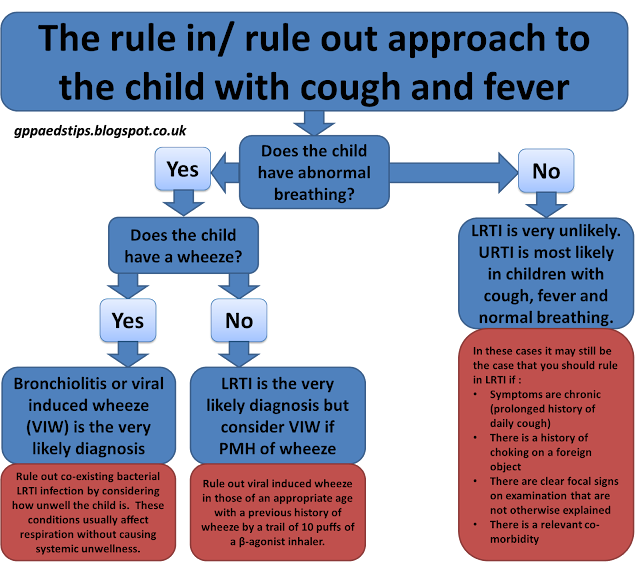

Because children who have experienced traumatic stress may seem restless, fidgety, or have trouble paying attention and staying organized, the symptoms of traumatic stress can be confused with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Read a guide for clinicians on deciding if it is ADHD or child traumatic stress.external icon

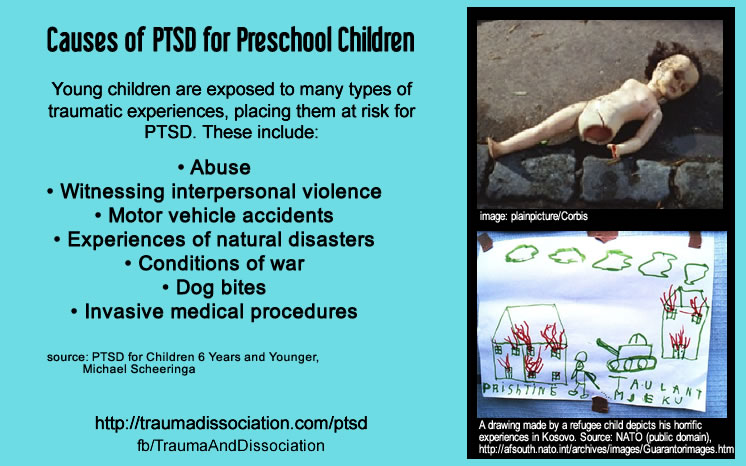

Examples of events that could cause PTSD include

- Physical, sexual, or emotional maltreatment

- Being a victim or witness to violence or crime

- Serious illness or death of a close family member or friend

- Natural or manmade disasters

- Severe car accidents

Learn more about PTSDexternal icon

Treatment for PTSD

Learn about the guidelines for diagnosing and treating PTSDexternal icon

The first step to treatment is to talk with a healthcare provider to arrange an evaluation. For a PTSD diagnosis, a specific event must have triggered the symptoms. Because the event was distressing, children may not want to talk about the event, so a health provider who is highly skilled in talking with children and families may be needed. Once the diagnosis is made, the first step is to make the child feel safe by getting support from parents, friends, and school, and by minimizing the chance of another traumatic event to the extent possible. Psychotherapy in which the child can speak, draw, play, or write about the stressful event can be done with the child, the family, or a group. Behavior therapy, specifically cognitive-behavioral therapy, helps children learn to change thoughts and feelings by first changing behavior in order to reduce the fear or worry. Medication may also be used to decrease symptoms.

Psychotherapy in which the child can speak, draw, play, or write about the stressful event can be done with the child, the family, or a group. Behavior therapy, specifically cognitive-behavioral therapy, helps children learn to change thoughts and feelings by first changing behavior in order to reduce the fear or worry. Medication may also be used to decrease symptoms.

Get help finding treatment

Here are tools to find a healthcare provider familiar with treatment options:

- Psychologist Locatorexternal icon, a service of the American Psychological Association (APA) Practice Organization.

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist Finderexternal icon, a research tool by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP).

- Find a Cognitive Behavioral Therapistexternal icon, a search tool by the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.

- If you need help finding treatment facilities, visit MentalHealth.

govexternal icon.

govexternal icon.

Prevention of PTSD

It is not known exactly why some children develop PTSD after experiencing stressful and traumatic events, and others do not. Many factors may play a role, including biology and temperament. But preventing risks for trauma, like maltreatment, violence, or injuries, or lessening the impact of unavoidable disasters on children, can help protect a child from PTSD.

Learn about public health approaches to prevent these risks:

- Protect the ones you love: Childhood injury prevention

- Bullying prevention external icon

- Child maltreatment prevention

- Youth violence prevention

- Caring for children in a disaster

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder In Children - StatPearls

Continuing Education Activity

Posttraumatic stress disorder constitutes exposure to a potentially traumatic event, followed by the manifestations of intrusive thoughts, avoidance of associated stimuli, negative modifications in mood, and alterations in arousal. This disorder can present differently in the pediatric population. This activity outlines the evaluation and management of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

This disorder can present differently in the pediatric population. This activity outlines the evaluation and management of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of posttraumatic stress disorder in children.

Review the evaluation of posttraumatic stress disorder in children.

Outline the management options available for posttraumatic stress disorder in children.

Explain the role of the interprofessional team in diagnosing pediatric patients with posttraumatic stress disorder.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental disorder that may develop in some children and adolescents after exposure to a traumatic event. Traumatic events may include incidents that involve serious harm to self or others and include accidents, natural disasters, sexual or physical trauma, natural disasters, and violence. [1]

[1]

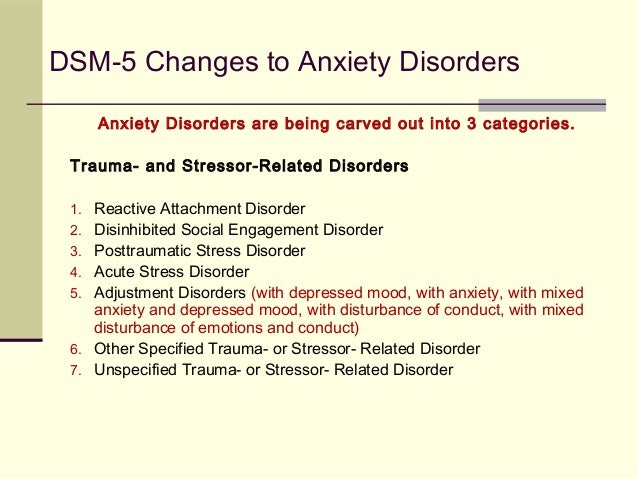

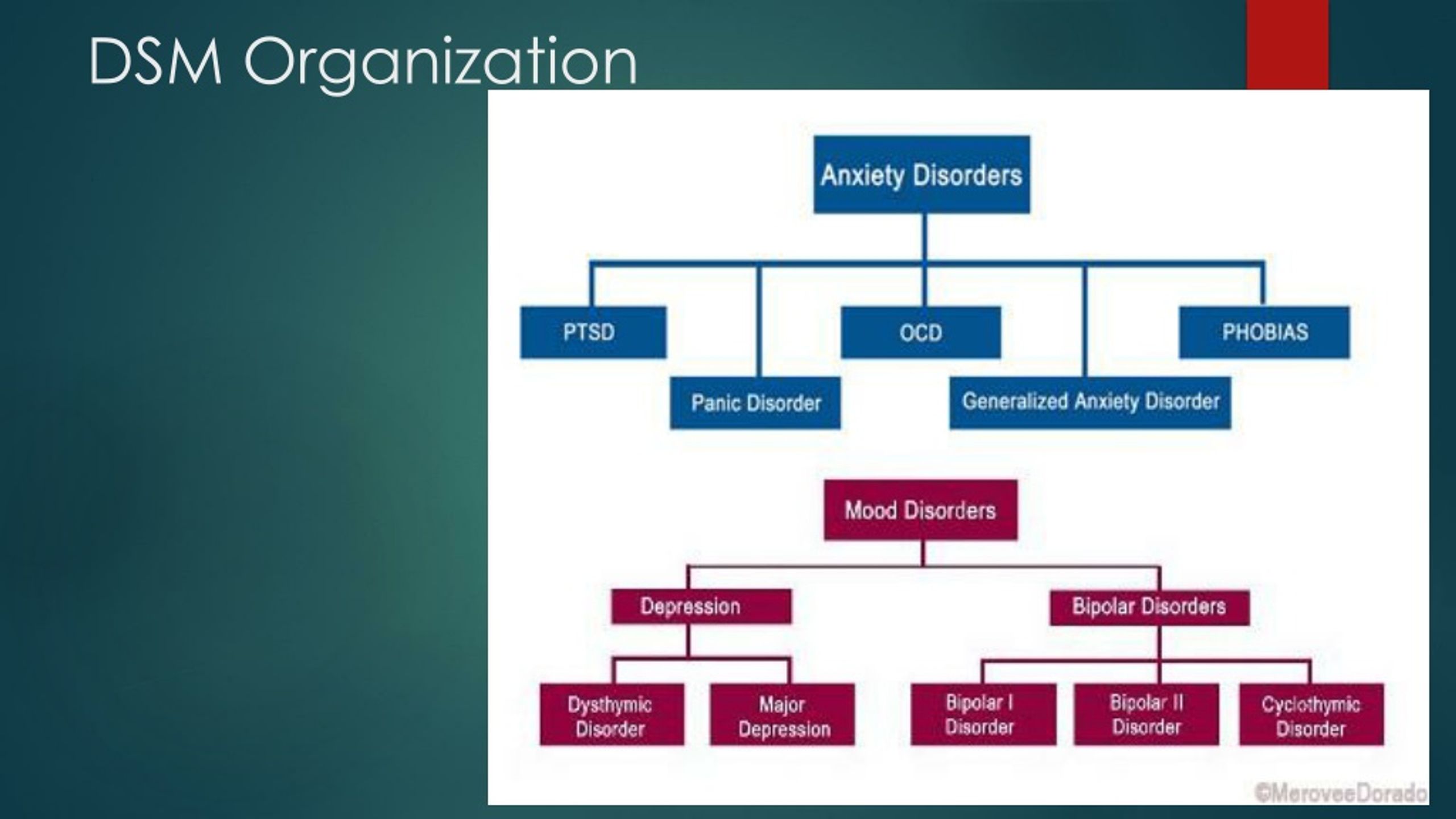

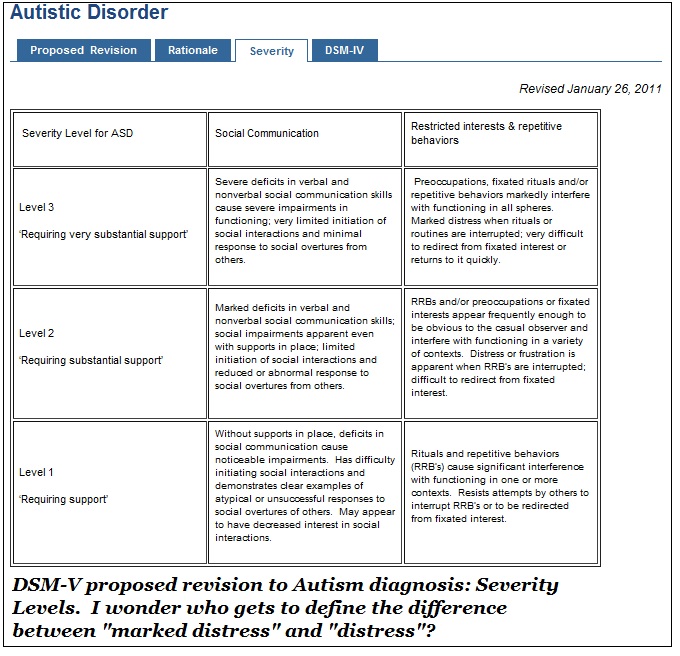

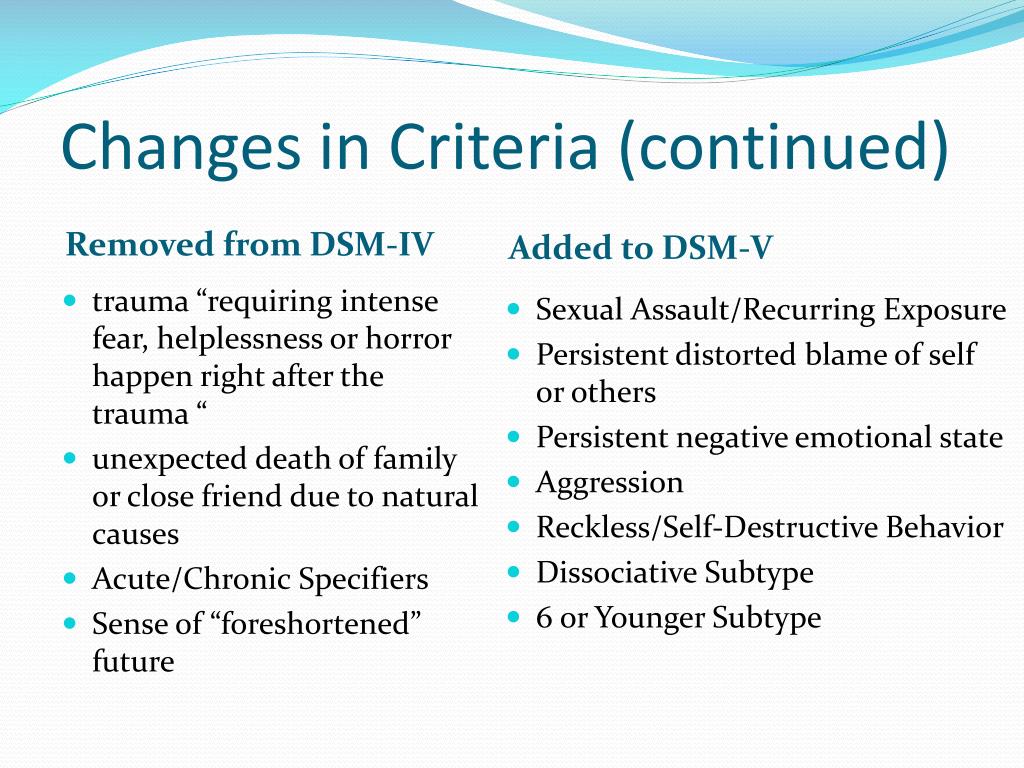

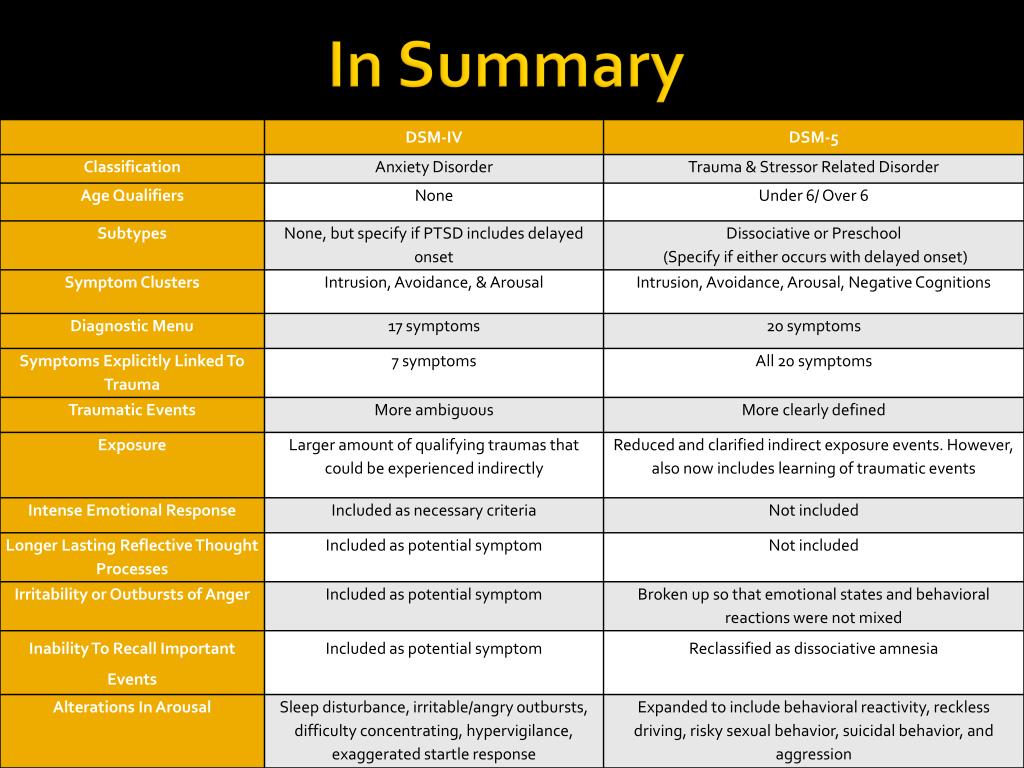

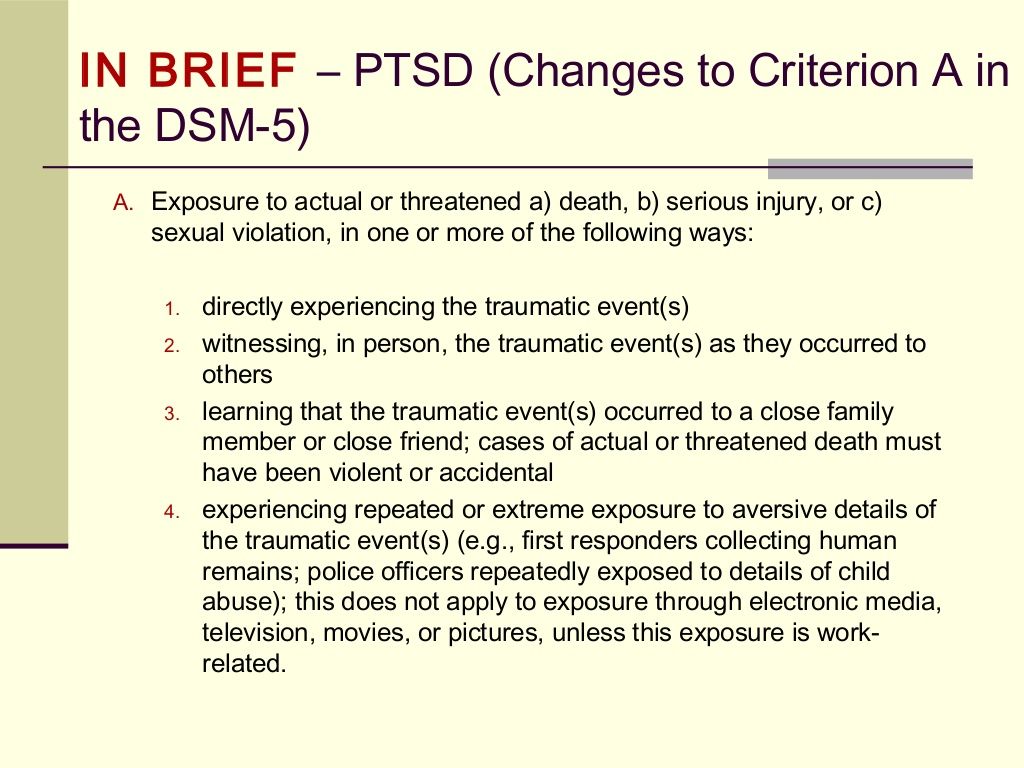

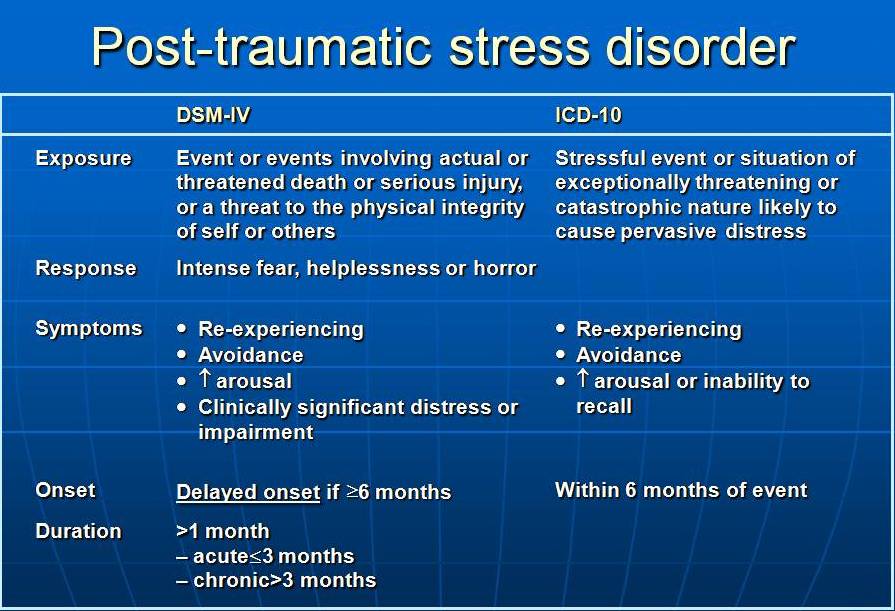

Since time immemorial, scientists have pursued the ever-elusive causal origins of disease processes. To the detriment of humanity, these endeavors frequently resulted in fruitless pursuits, as we still can only postulate the etiologies of many illnesses. Thus, the causal nature of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) places it in the company of a scant few psychiatric diagnoses where etiology is known. The temporal association between the event exposure and the subsequent symptom manifestation is not simply a post hoc fallacy. Not to be misled by the putative simplistic nature of the etiology, the consequent psychiatric sequelae can, in turn, be debilitating. Moreover, recent studies have unmasked unsettling discoveries regarding pediatric considerations in the setting of PTSD. It has been suggested that a substantial number of children have gone inappropriately undiagnosed because of the insufficient sensitivities of previous guidelines. Children often react differently to stressful events, and because of this, the pediatric phenomenology of PTSD differs from that of adults. [2] The transition from DSM IV to DSM-V acknowledges this inconsistency, made evident by the additional criteria specific to PTSD for children six years or younger.

[2] The transition from DSM IV to DSM-V acknowledges this inconsistency, made evident by the additional criteria specific to PTSD for children six years or younger.

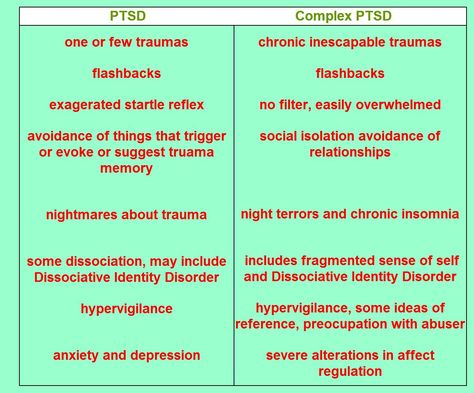

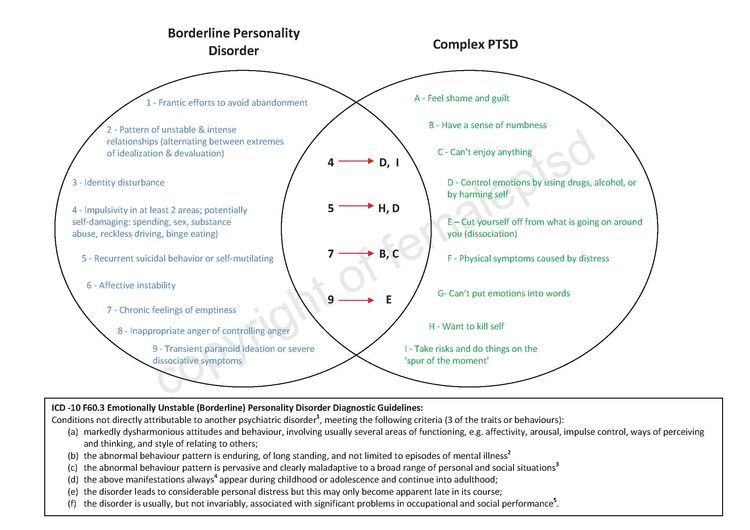

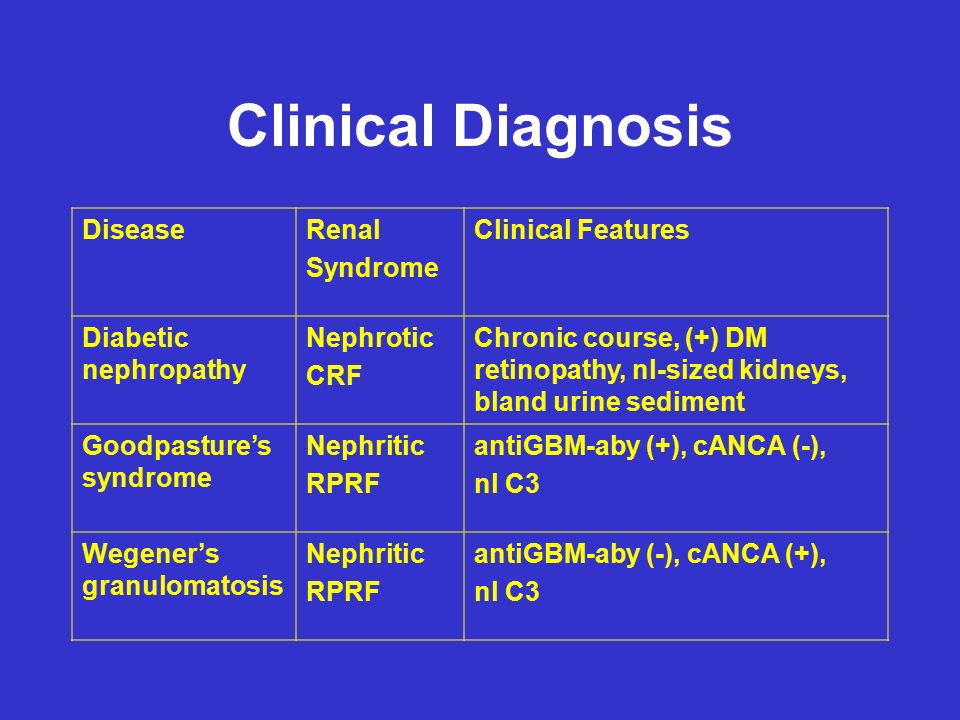

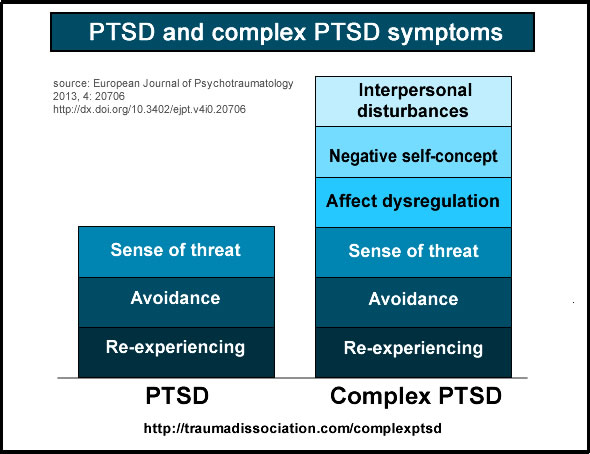

PTSD is defined by four symptom clusters: avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, intrusion, and hyperarousal per DSM-5. The consequences of PTSD are often deleterious, with adverse outcomes in physical and mental health besides impaired social and occupational functioning.[3]

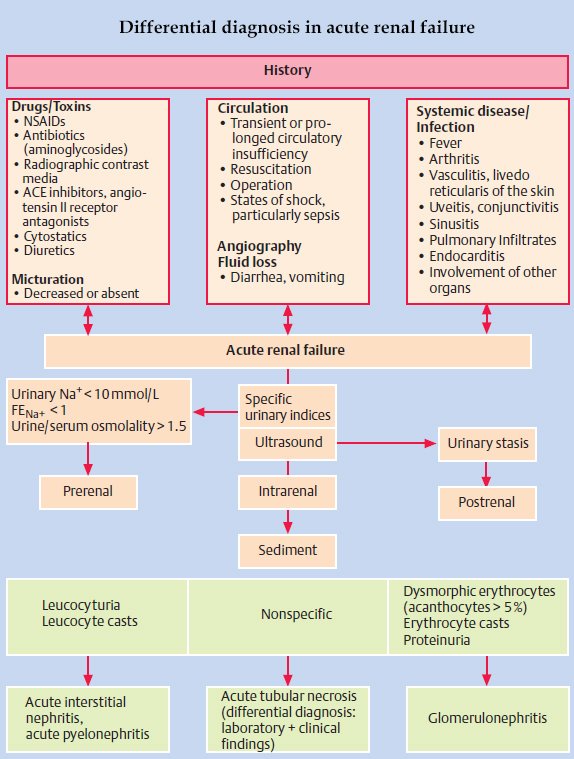

Etiology

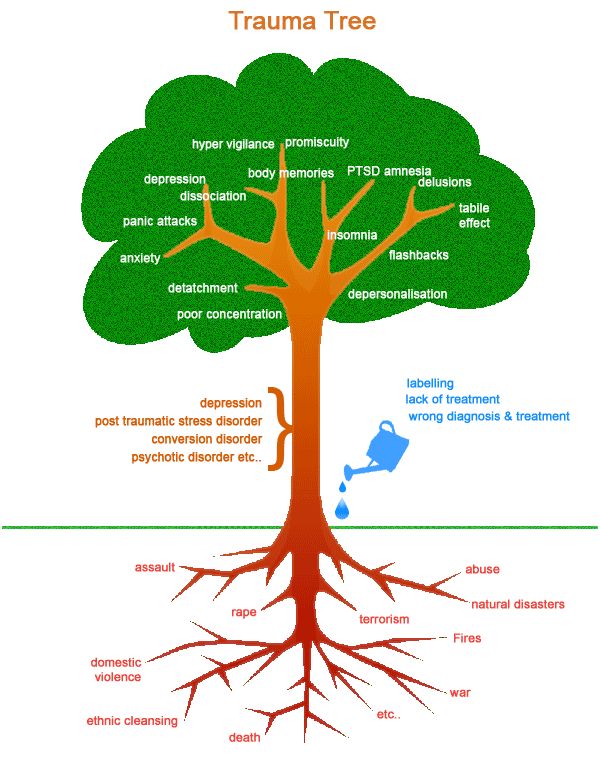

As mentioned in the introduction, there is a direct causal relationship between exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTEs) and the onset of PTSD. The most commonly reported PTEs in the pediatric population include physical injuries, domestic violence, and natural disasters.[4][5]

Epidemiology

One study reports that up to 60% of children and adolescents have been exposed to a PTE.[6][7] Of this exposed population, an estimated 30% subsequently develop PTSD symptomatology; most will only experience ephemeral symptoms, whereas a few unfortunate individuals will experience more chronic life-long sequelae. Current estimates suggest 10% of children less than 18 years of age are diagnosed with PTSD, with girls four times more likely than boys to develop it.[8]

Current estimates suggest 10% of children less than 18 years of age are diagnosed with PTSD, with girls four times more likely than boys to develop it.[8]

History and Physical

Common to both the adult and pediatric population are the foundational elements of post-traumatic stress disorder: re-experiencing of the trauma through intrusive and recurrent thoughts, avoidance of associated stimuli, negative modifications in mood, and alterations in reactivity and arousal. However, the phenomenology of PTSD in younger demographics is often more complex and can mimic variant internalizing and externalizing disorders.[6] It is likely that adults will relegate manifestations of PTSD as disagreeable youthful behavior.[9]

Internalizing and externalizing symptomatology that can manifest in the setting of PTSD include separation anxiety, shame, guilt, low frustration tolerance, hyperarousal, impulsivity, temper outbursts, hostility, defiance, aggression, irritability, and mood changes. [10][11] Moreover, complex trauma disorder can present even more ambiguously in children. Whereas a more discrete change in behavior transpires in acute PTE, exposure to protracted PTEs incites more insidious and pervasive complications.[12][3][13][12]

[10][11] Moreover, complex trauma disorder can present even more ambiguously in children. Whereas a more discrete change in behavior transpires in acute PTE, exposure to protracted PTEs incites more insidious and pervasive complications.[12][3][13][12]

Evaluation

It is critical in the evaluation of pediatric post-traumatic stress disorder that the clinician obtains both the child’s and caregivers’ reports.[14] Once the respective histories have been elicited, the clinician will use diagnostic tools to assess for the existence of PTSD. In the transition to DSM-V, specific diagnostic criteria for PTSD in those less than six years of age were added.

DSM-V Diagnostic Criteria for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder for Children 6 years and Younger: [Reference: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), American Psychiatric Association, Arlington 2013].

In children six years and younger, exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence in one (or more) of the following ways:

Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s)

Witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to others, especially primary caregivers

Does not include events that are witnessed only in electronic media, television, movies, or pictures

Learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a parent or caregiving figure

Presence of one (or more) of the following intrusion symptoms associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning after the traumatic event(s) occurred;

Recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s)

Recurrent distressing dreams in which the content and/or effect of the dream are related to the traumatic event(s)

Dissociative reactions in which the child feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were recurring

Intense or prolonged psychological distress at exposure to internal or external clues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s)

Marked physiological reactions to reminders of the traumatic event(s)

One (or more) of the following symptoms, representing either persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event(s) or negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event(s), must be present, beginning after the event(s) or worsening after the event(s)

Persistent Avoidance of Stimuli

Avoidance of or efforts to avoid activities, places, or physical reminders that arouse recollections of the traumatic event(s)

Avoidance of or efforts to avoid people, conversations, or interpersonal situations that arouse recollections of the traumatic event(s)

Negative Alterations in Cognitions

Substantially increased frequency of negative emotional states.

Markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities, including constriction of play.

Socially withdrawn behavior

Persistent reduction in the expression of positive emotions

Alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning or worsening after the traumatic event(s) occurred, as evidenced by two (or more) of the following:

Irritable behavior and angry outbursts (with little or no provocation) typically expressed as verbal or physical aggression toward people or objects (including extreme temper tantrums)

Hypervigilance

Exaggerated startle response

Problems with concentration

Sleep disturbance

The duration of the disturbance is more than one month.

The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment[15]

Specify whether:

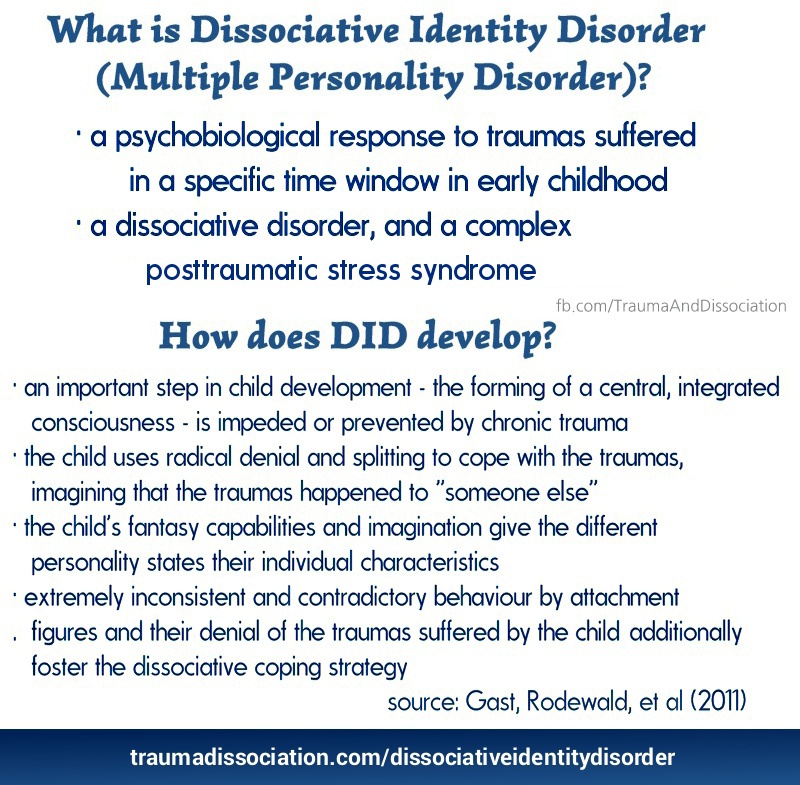

With Dissociative symptoms:

Depersonalization

Derealization

Specify if:

(For children greater than six years old, the clinician will refer to DSM-V criteria for adults)

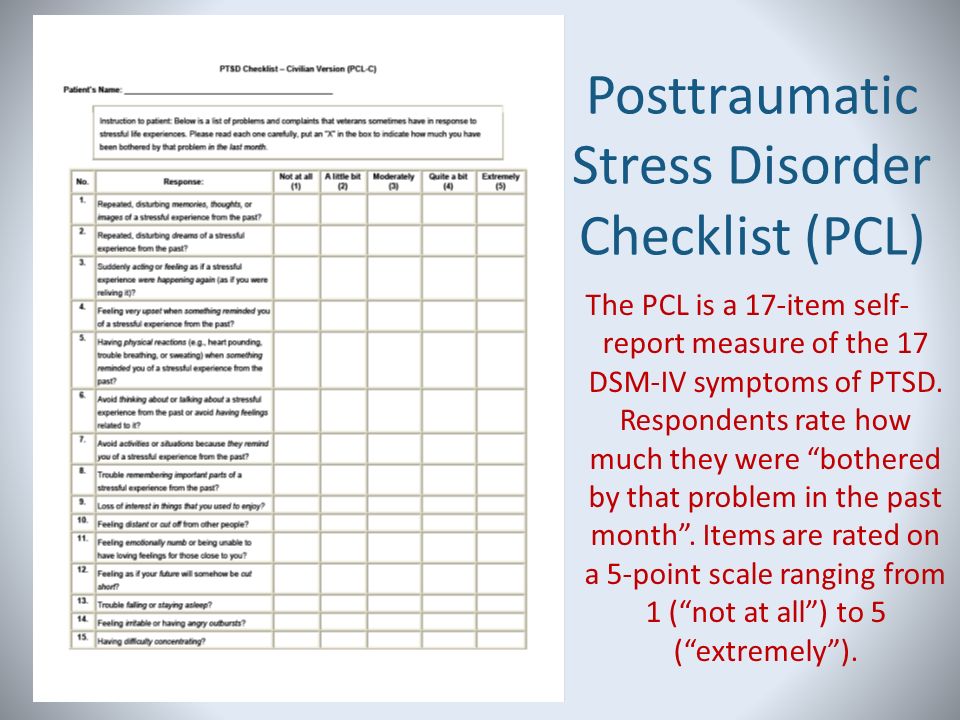

Additional evidence-based screening tools have been commonly implemented in the clinical setting. These include the UCLA Posttraumatic Stress Disorder – Reaction Index (UCLA-PTSD-RI), the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC), and The Screening Tool for Early Predictors of PTSD (STEPP).[6][16]

These include the UCLA Posttraumatic Stress Disorder – Reaction Index (UCLA-PTSD-RI), the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC), and The Screening Tool for Early Predictors of PTSD (STEPP).[6][16]

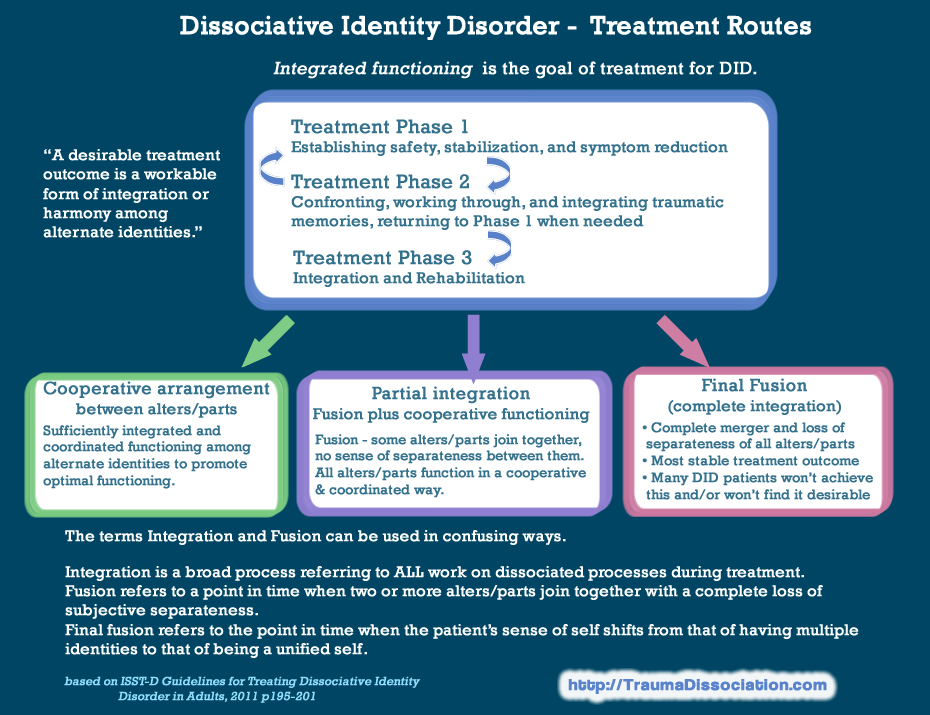

Treatment / Management

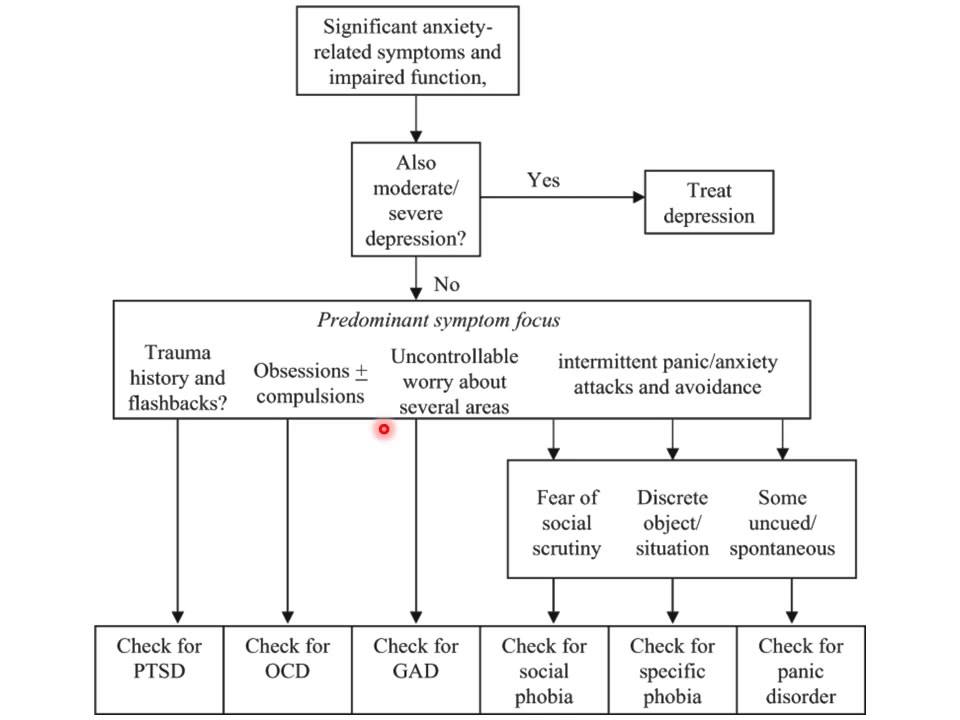

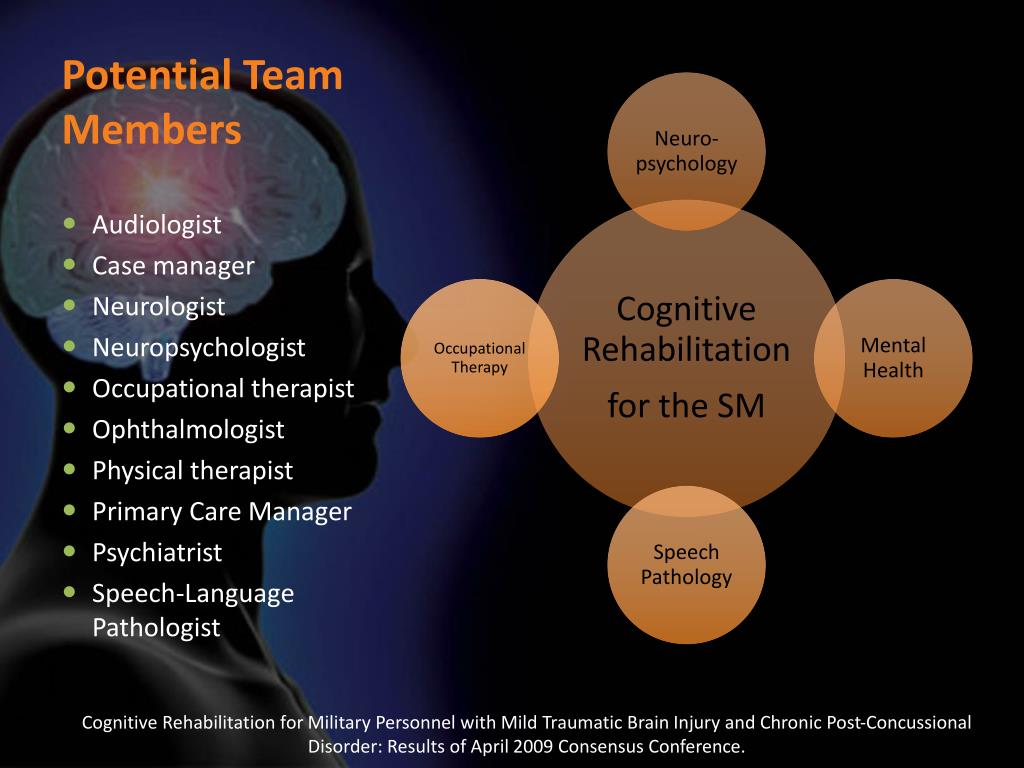

Psychotherapy is encouraged by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) as the first-line treatment in the setting of pediatric PTSD.[6] Trauma-centered cognitive-behavioral therapy currently has the most unequivocal evidence supporting its implementation in the treatment of pediatric PTSD.[17] Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR) is a popular alternative. However, more research is required to properly assess its efficaciousness.[18]

Other therapies include play therapy, psychological first aid, and multisystemic therapy. Because of developmental neurobiological differences between youth and adult patients, the consensus remains ambiguous regarding the administration of pharmacological agents.[19] Of the psychotropic alternatives, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) have the most support. Lastly, in moderate to severe cases, children should be referred to specialists who are trained to treat PTSD in the pediatric population.

Lastly, in moderate to severe cases, children should be referred to specialists who are trained to treat PTSD in the pediatric population.

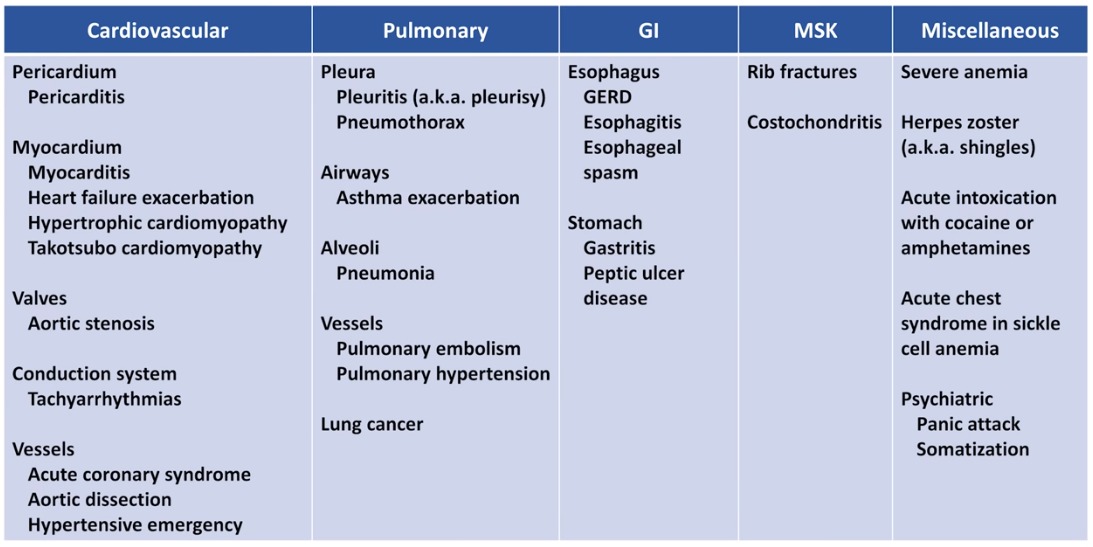

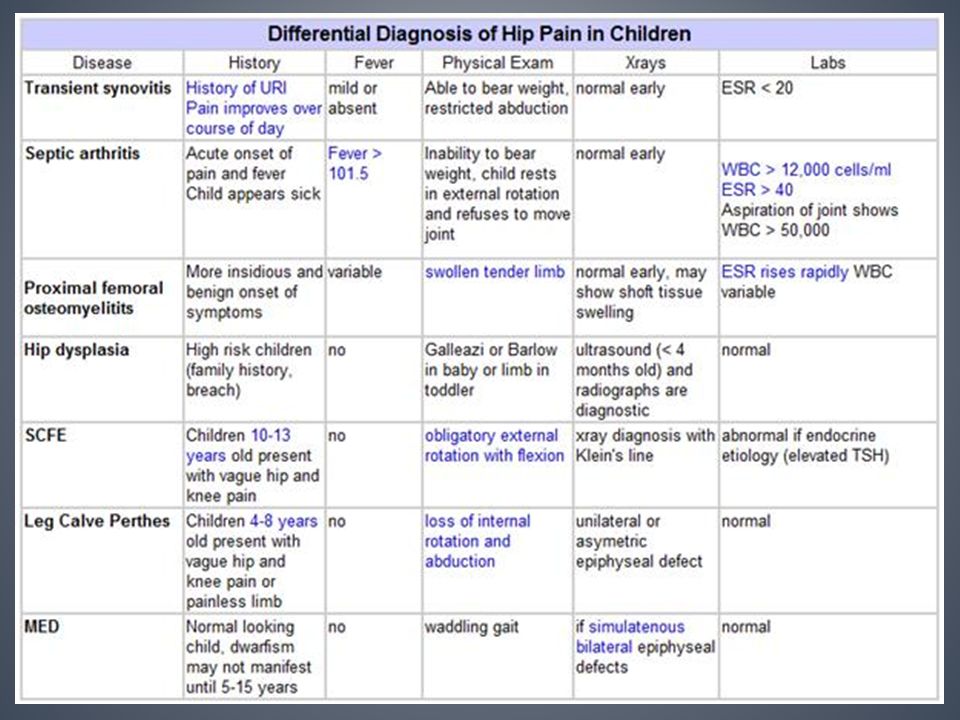

Differential Diagnosis

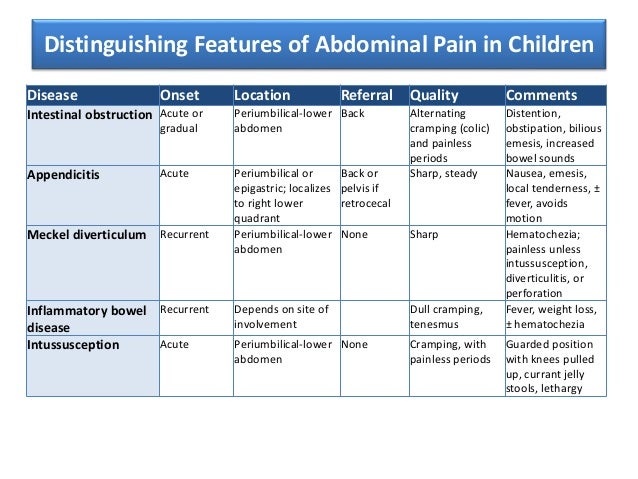

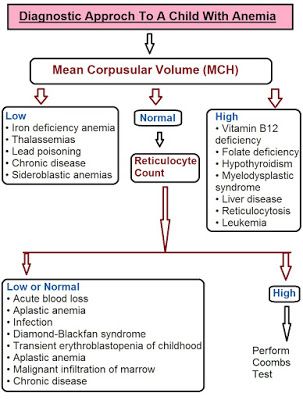

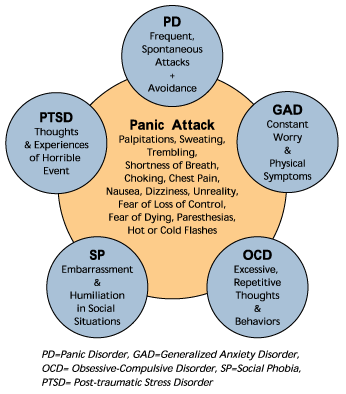

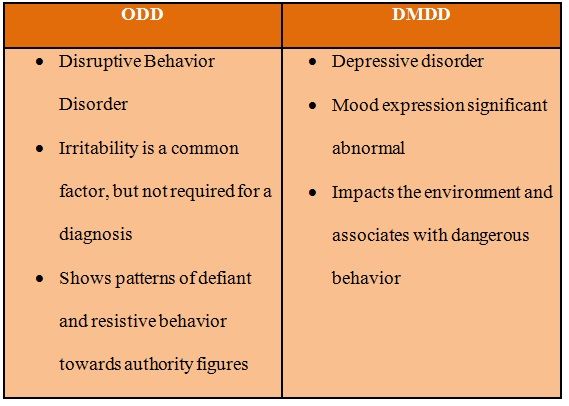

The phenomenology of post-traumatic stress disorder in the pediatric setting can mislead clinicians towards a misdiagnosis. Disorders that can mimic the aforementioned internalizing and externalizing features of PTSD include major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.[20] Additional differentials in common with adult PTSD include adjustment disorder, acute stress disorder, panic disorder, depersonalization or derealization disorder, and malingering.[21]

Prognosis

Chronic PTSD can cause significant distress in a child’s life and ultimately result in functional disabilities.[22][23] Fortunately, research suggests that prompt recognition and intervention in at-risk youths can significantly obviate grim psychiatric sequelae.

Complications

Complications arise secondary to functional impairments resulting from psychic stress. To combat these impairments, patients commonly resort to self-medication; such a stratagem involves inappropriate use of anxiolytics, alcohol, or recreational drugs. Unfortunately, these immature coping mechanisms exacerbate the psychic illness, thus further debilitating the patient, precipitating an elegiac positive feedback loop.[24]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prior to initial exposure to post-traumatic events, providers and educators can implement proactive measures to equip the youth - especially those at high risk - with beneficial coping skills, safety planning, and psychoeducation.[25] As most families will initially present to their primary care provider for assistance, it is imperative for clinicians to be cognizant of the phenomenology of PTSD in children.[26] Primary healthcare teams are, for lack of a better colloquialism, ‘the first line of defense’ in the setting of PTE. [27]

[27]

Providers suspicious of impending manifestations of PTSD in the acute aftermath of a PTE should ardently monitor the patient and enlighten the family regarding salient features to be aware of in this condition. Furthermore, some studies suggest that those who do not meet the full diagnostic threshold for PTSD may benefit from a more flexible dimensional perspective, as they still may be at risk for developing undesirable psychiatric sequelae.[28]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a debilitating disorder. It can cause life-long impairment and dysfunction. In the pediatric setting, it can be even more deleterious, as it can go undiagnosed and thus untreated for an extended period of time. Because of the unique presentation in the pediatric population, it is exigent that healthcare workers remain vigilant and aware of the onset of symptomatology. Primary care physicians, pediatricians, nurse practitioners, psychotherapists, and licensed clinical social workers will often be the 'first line of defense,' as parents will often bring their children to them, before considering a psychiatrist. Thus, primary care providers must remain informed regarding the phenomenology in this population. They should not hesitate to refer to a specialist. Interprofessional relations will most benefit the patient.

Thus, primary care providers must remain informed regarding the phenomenology in this population. They should not hesitate to refer to a specialist. Interprofessional relations will most benefit the patient.

"This research was supported (in whole or part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities."

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Birkeland MS, Holt T, Ormhaug SM, Jensen TK. Perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms in children and youth in therapy: A parallel process latent growth curve model. Behav Res Ther. 2020 Jun 01;132:103655. [PubMed: 32590214]

- 2.

de Vries AP, Kassam-Adams N, Cnaan A, Sherman-Slate E, Gallagher PR, Winston FK.

Looking beyond the physical injury: posttraumatic stress disorder in children and parents after pediatric traffic injury. Pediatrics. 1999 Dec;104(6):1293-9. [PubMed: 10585980]

Looking beyond the physical injury: posttraumatic stress disorder in children and parents after pediatric traffic injury. Pediatrics. 1999 Dec;104(6):1293-9. [PubMed: 10585980]- 3.

Malejko K, Tumani V, Rau V, Neumann F, Plener PL, Fegert JM, Abler B, Straub J. Neural correlates of script-driven imagery in adolescents with interpersonal traumatic experiences: A pilot study. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2020 Sep 30;303:111131. [PubMed: 32585577]

- 4.

McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Green CE. Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. J Fam Psychol. 2006 Mar;20(1):137-142. [PubMed: 16569098]

- 5.

Pronczuk J, Surdu S. Children's environmental health in the twenty-first century. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008 Oct;1140:143-54. [PubMed: 18991913]

- 6.

Ramsdell KD, Smith AJ, Hildenbrand AK, Marsac ML. Posttraumatic stress in school-age children and adolescents: medical providers' role from diagnosis to optimal management.

Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2015;6:167-180. [PMC free article: PMC5683267] [PubMed: 29388603]

Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2015;6:167-180. [PMC free article: PMC5683267] [PubMed: 29388603]- 7.

Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2009 Jul;33(7):403-11. [PubMed: 19589596]

- 8.

Miller-Graff LE, Howell KH. Posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories among children exposed to violence. J Trauma Stress. 2015 Feb;28(1):17-24. [PubMed: 25644072]

- 9.

Ziegler MF, Greenwald MH, DeGuzman MA, Simon HK. Posttraumatic stress responses in children: awareness and practice among a sample of pediatric emergency care providers. Pediatrics. 2005 May;115(5):1261-7. [PubMed: 15867033]

- 10.

Dykman RA, McPherson B, Ackerman PT, Newton JE, Mooney DM, Wherry J, Chaffin M. Internalizing and externalizing characteristics of sexually and/or physically abused children. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 1997 Jan-Mar;32(1):62-74. [PubMed: 9105915]

- 11.

Kletter H, Weems CF, Carrion VG. Guilt and posttraumatic stress symptoms in child victims of interpersonal violence. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009 Jan;14(1):71-83. [PubMed: 19103706]

- 12.

Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, Petkova E. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. J Trauma Stress. 2009 Oct;22(5):399-408. [PubMed: 19795402]

- 13.

LoSavio ST, Hale WJ, Moring JC, Blankenship AE, Dondanville KA, Wachen JS, Mintz J, Peterson AL, Litz BT, Young-McCaughan S, Yarvis JS, Resick PA. Efficacy of individual and group cognitive processing therapy for military personnel with and without child abuse histories. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2021 May;89(5):476-482. [PubMed: 34124929]

- 14.

Kassam-Adams N, García-España JF, Miller VA, Winston F. Parent-child agreement regarding children's acute stress: the role of parent acute stress reactions.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006 Dec;45(12):1485-93. [PubMed: 17135994]

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006 Dec;45(12):1485-93. [PubMed: 17135994]- 15.

Schellong J, Hanschmidt F, Ehring T, Knaevelsrud C, Schäfer I, Rau H, Dyer A, Krüger-Gottschalk A. [Diagnostics of posttraumatic stress disorder according to DSM-5 and ICD-11]. Nervenarzt. 2019 Jul;90(7):733-739. [PubMed: 30643956]

- 16.

Winston FK, Kassam-Adams N, Garcia-España F, Ittenbach R, Cnaan A. Screening for risk of persistent posttraumatic stress in injured children and their parents. JAMA. 2003 Aug 06;290(5):643-9. [PubMed: 12902368]

- 17.

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: initial findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996 Jan;35(1):42-50. [PubMed: 8567611]

- 18.

Seidler GH, Wagner FE. Comparing the efficacy of EMDR and trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of PTSD: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Med. 2006 Nov;36(11):1515-22.

[PubMed: 16740177]

[PubMed: 16740177]- 19.

Pervanidou P. Biology of post-traumatic stress disorder in childhood and adolescence. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008 May;20(5):632-8. [PubMed: 18363804]

- 20.

Glod CA, Teicher MH. Relationship between early abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, and activity levels in prepubertal children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996 Oct;35(10):1384-93. [PubMed: 8885593]

- 21.

Radoš SN, Matijaš M, Anđelinović M, Čartolovni A, Ayers S. The role of posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms in mother-infant bonding. J Affect Disord. 2020 May 01;268:134-140. [PubMed: 32174471]

- 22.

Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 May;64(5):577-84. [PubMed: 17485609]

- 23.

Zatzick DF, Jurkovich GJ, Fan MY, Grossman D, Russo J, Katon W, Rivara FP. Association between posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms and functional outcomes in adolescents followed up longitudinally after injury hospitalization.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008 Jul;162(7):642-8. [PubMed: 18606935]

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008 Jul;162(7):642-8. [PubMed: 18606935]- 24.

Zatzick DF, Jurkovich GJ, Gentilello L, Wisner D, Rivara FP. Posttraumatic stress, problem drinking, and functional outcomes after injury. Arch Surg. 2002 Feb;137(2):200-5. [PubMed: 11822960]

- 25.

Pfefferbaum B, Varma V, Nitiéma P, Newman E. Universal preventive interventions for children in the context of disasters and terrorism. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014 Apr;23(2):363-82, ix-x. [PMC free article: PMC3964365] [PubMed: 24656585]

- 26.

Davidson EJ, Silva TJ, Sofis LA, Ganz ML, Palfrey JS. The doctor's dilemma: challenges for the primary care physician caring for the child with special health care needs. Ambul Pediatr. 2002 May-Jun;2(3):218-23. [PubMed: 12014983]

- 27.

Leslie LK, Sarah R, Palfrey JS. Child health care in changing times. Pediatrics. 1998 Apr;101(4 Pt 2):746-51; discussion 751-2. [PubMed: 9544178]

- 28.

Broman-Fulks JJ, Ruggiero KJ, Green BA, Smith DW, Hanson RF, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE. The latent structure of posttraumatic stress disorder among adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2009 Apr;22(2):146-52. [PubMed: 19319918]

Stress and post-traumatic condition in children

We treat children according to the principles of evidence-based medicine: we choose only those diagnostic and treatment methods that have proven their effectiveness. We will never prescribe unnecessary examinations and medicines!

Make an appointment via WhatsApp

Prices Doctors

The first children's clinic of evidence-based medicine in Moscow

No unnecessary examinations and medicines! We will prescribe only what has proven effective and will help your child.

Treatment according to world standards

We treat children with the same quality as in the best medical centers in the world.

The best team of doctors in Fantasy!

Pediatricians and subspecialists Fantasy - highly experienced doctors, members of professional societies. Doctors constantly improve their qualifications, undergo internships abroad.

Doctors constantly improve their qualifications, undergo internships abroad.

Ultimate treatment safety

We made pediatric medicine safe! All our staff work according to the most stringent international standards JCI

We have fun, like visiting best friends

Game room, cheerful animator, gifts after the reception. We try to make friends with the child and do everything to make the little patient feel comfortable with us.

You can make an appointment by calling or by filling out the form on the site

Other services of the section "Psychology"

- Child psychologist consultation

- Complete diagnosis of the child's mental health (Joint appointment with a neurologist, psychologist, psychiatrist)

Surveys

- Diagnostic session

- Course of psychological correction / psychotherapy

Frequent calls

- Family problems

- The appearance of the baby in the family

- "No one is friends with me!" - Difficulty communicating with peers

- "Again deuce" - learning difficulties, conflicts with teachers

- “I won’t go to kindergarten / school anymore!” - difficulty adapting

- Career guidance for teenagers nine0034

- Psychosomatic disorders in children

- Emotional difficulties in children

- Transitional age (crisis of 3 years, school, teenage difficulties)

- Addictions in children and adolescents

- Panic attacks in children

Online payment nine0003

Documents online

Online services

Post-traumatic stress disorder in young children

Alexandra De Young, PhD, Justin Kenardi, PhD

National Research Center for Disorders and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Australia

(English). Translation: June 2015

Translation: June 2015

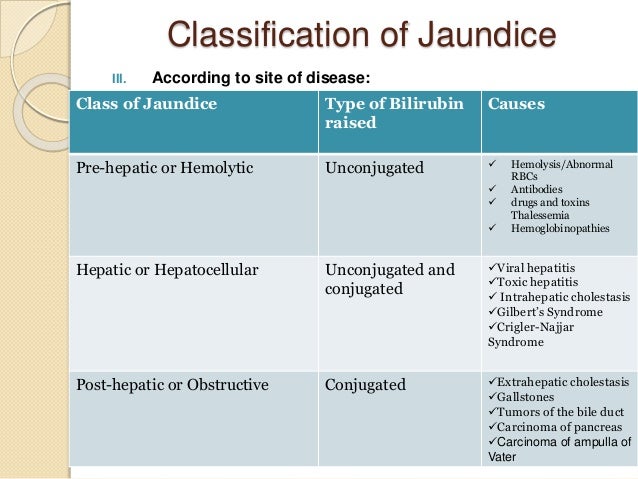

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the most severe and debilitating disorders associated with trauma. According to research, young children, as well as older children and adolescents, commonly exhibit three of the traditional symptoms of PTSD: re-experiencing the event (through nightmares or acting out traumatic events), seeking to avoid being reminded of the event, and psychological overexcitation (for example, , irritability, sleep disturbance, unmotivated shivering). nine0108 1 However, research suggests that the PTSD features listed in The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 2 do not adequately reflect the specificity of onset of symptoms in infants and preschool children. The Guidelines also underestimate the number of children experiencing post-traumatic stress and subsequent deterioration in health. nine0108 3 Accordingly, new research is encouraging the inclusion of a subtype of PTSD occurring in preschool children in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. 4.5

nine0108 3 Accordingly, new research is encouraging the inclusion of a subtype of PTSD occurring in preschool children in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. 4.5

Frequency, course and consequences of reactions to trauma months after the traffic accident (RTA) 6 or burn injuries 7 ; in 14.3–25% of cases, within two months after receiving various types of injuries (for example, burns, bullet wounds, road accidents, injuries during sports or during the game), 8.9 in 10% of cases, within six months after an accident or burn injuries 6.8 and in 13.2% of cases - within an average of 15 months after burn injuries.10 Signs of age-specific PTSD appear in 26-60% 1,3,11 cases as a result of physical or sexual violence. Our study showed that young children develop depression, separation anxiety disorder, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and specific phobias due to burn injuries, 8 , and that these disorders are highly concomitant symptoms of PTSD.

Studies in children of all ages have shown that, if left untreated, PTSD can develop into a chronic, debilitating form. nine0108 8,12,13 The results of this study are troubling given that the neurophysiological systems in young children, including stress modulation and emotion regulation, are still in rapid development. 14 In addition, childhood trauma is associated with permanent structural 15 and functional 16 brain damage, as well as with the onset of psychiatric disorders, 17 health risk behaviors and related physical health conditions in adults. 18 Thus, trauma in early childhood can have much more severe consequences on the developmental trajectory than trauma sustained later in development.

The role of parents

When working with children, it is very important to realize that the trauma itself and the child's reaction to it is a serious test for parents, which can also become a source of chronic stress. Research has shown that approximately 25% of parents experience clinically elevated levels of acute stress, PTSD, anxiety, depression, and stress within the first six months of a child's trauma. nine0108 19-21 Although most parents remain relatively resilient and their stress levels eventually return to clinical normal, parental distress during the acute stress stage contributes to the development and persistence of traumatic symptoms in affected children. 19,20,22

Research has shown that approximately 25% of parents experience clinically elevated levels of acute stress, PTSD, anxiety, depression, and stress within the first six months of a child's trauma. nine0108 19-21 Although most parents remain relatively resilient and their stress levels eventually return to clinical normal, parental distress during the acute stress stage contributes to the development and persistence of traumatic symptoms in affected children. 19,20,22

It is generally accepted that the quality of attachment of children and parents to each other, the mental health of parents and their parenting actions are key factors influencing a child's recovery from trauma. nine0108 14,23,24 For young children, relationships with parents are especially important because children do not have sufficient adaptive capacity to regulate strong emotions on their own. Thus, they depend on a sensitive and emotionally open educator who can help them regulate their emotional response in times of distress. 14.23 In addition, young children especially rely on their parents' emotions to understand how to interpret or respond to an event. In the future, children can imitate their parents' reaction to fear and their inadequate adaptive reactions. nine0108 25 Parents can also directly influence the child's contact with reminders of the trauma (for example, avoid discussing what happened) and thus prevent the child from adapting to the perception of the event. 25

14.23 In addition, young children especially rely on their parents' emotions to understand how to interpret or respond to an event. In the future, children can imitate their parents' reaction to fear and their inadequate adaptive reactions. nine0108 25 Parents can also directly influence the child's contact with reminders of the trauma (for example, avoid discussing what happened) and thus prevent the child from adapting to the perception of the event. 25

The influence of adverse psychological reactions on the relationship between children and parents, the development of traumatic symptoms in the child, combined with the mental suffering of parents, are important arguments inducing to pay more attention to the needs of parents in order to reduce their level of experience and stimulate their ability to support children in difficult times. Adequate measures aimed at alleviating the mental illness of the child and parents, as well as improving relations between them, will have a beneficial effect on the process of inhibiting the development of post-traumatic reactions in parents and children. However, there is only preliminary evidence to support these types of interventions during an exacerbation, and more research is needed on this issue. nine0003

However, there is only preliminary evidence to support these types of interventions during an exacerbation, and more research is needed on this issue. nine0003

Early prevention and correction measures

Unfortunately, most children and their parents who experience psychological difficulties after trauma are not diagnosed with characteristic symptoms, as a result of which both children and parents do not receive adequate support. Taking into account the prevalence of injuries, as well as the fact that early childhood is a sensitive period of brain development, it is necessary to introduce effective measures that can reduce the risk of developing chronic post-traumatic stress reactions in children and parents. It is advisable to take such measures in an environment with an increased risk of stress reactions, for example, in a medical institution. This solution would reduce the risk of traumatic stress reactions or even prevent them by conducting an examination and implementing a program of preventive measures. nine0108 26 Early diagnosis of severe symptoms and appropriate action in families at risk will help prevent problems from occurring and entrenching, or at least minimize the impact of these problems on the child, family and society. However, the primary task is to learn to distinguish between categories of patients experiencing a short-term mental disorder and those at risk of developing chronic PTSD, without creating additional overload for filled medical institutions. Psychometrically verified examination methods for very young children do not exist, which is a significant shortcoming in this area. nine0003

nine0108 26 Early diagnosis of severe symptoms and appropriate action in families at risk will help prevent problems from occurring and entrenching, or at least minimize the impact of these problems on the child, family and society. However, the primary task is to learn to distinguish between categories of patients experiencing a short-term mental disorder and those at risk of developing chronic PTSD, without creating additional overload for filled medical institutions. Psychometrically verified examination methods for very young children do not exist, which is a significant shortcoming in this area. nine0003

To date, most research has focused on the treatment of chronic PTSD rather than early prevention of its symptoms. Both in children's and adult literature, there is no data on which categories of patients need preventive measures at an early stage, what duration and content these measures should have. 27 To date, systematic reviews suggest that continuous cognitive behavioral trauma therapy (CBT) is most effective when administered within the first three months after the event. nine0108 27

nine0108 27

Research on children suggests that preventive action based on incident information up to two weeks after an injury can reduce anxiety symptoms in children at 1 28 and 6 months after the event developments. 29 In addition, Landolt et al received a positive response to a single session of preventive therapy aimed at managing symptoms of depression and behavioral problems in a group of preteens (7-11 years old) affected by road traffic accidents. nine0108 30 Berkowitz and colleagues 31 created the only individualized prevention program (4 sessions for a child with a parent/guardian, including diagnosis, psychological self-help training and coping skills) for children 7-17 years old. The program has shown its effectiveness in reducing the manifestations of PTSD and various post-traumatic symptoms.

However, there are no published studies on the effectiveness of preventive post-traumatic psychological interventions for young children (under six years of age). However, Scheering's research has shown that 12 sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy, built in accordance with a special plan for PTSD, conducted with children aged 3-6 years who experienced a variety of traumatic events, showed their appropriateness and effectiveness in reducing existing post-traumatic stress symptoms. nine0108 32

However, Scheering's research has shown that 12 sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy, built in accordance with a special plan for PTSD, conducted with children aged 3-6 years who experienced a variety of traumatic events, showed their appropriateness and effectiveness in reducing existing post-traumatic stress symptoms. nine0108 32

Few studies look at the preventive therapy component for adults to prevent post-trauma disorders in children. Kenardy et al found that psychological self-help training provided to parents within 72 hours of an accident was effective in reducing parental post-traumatic symptoms up to 6 months after the accident. 28 Melnyk et al 33 examined the effectiveness of a prevention program in parents of children aged 2-7 years under close pediatric supervision. The researchers found that parents in the prevention group had markedly reduced levels of stress, depression, and PTSD symptoms, and their children experienced fewer internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems after discharge. nine0003

nine0003

Evidence-based recommendations for the prevention of PTSD in young children require research. However, Landolt et al., based on the results of a recent meta-analysis, argue that early preventive measures help identify children at risk. These activities include several sessions of training in psychological self-help, individual adaptation skills, involvement of parents in the process and familiarization with various forms of traumatic phenomena. nine0108 34

Advice for parents, services, and policy

The phenomenon of post-traumatic stress disorder in young children has received little attention so far. Health care providers should monitor children more closely for signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. This may require training and retraining of staff. Mass standardized screening is ideal, but diagnosing groups of children at risk may be more cost-effective. In addition, any screening program must be integrated with a clinical setting that provides opportunities for appropriate care. Parental distress is a significant factor influencing post-traumatic reactions in children. However, in medical institutions this criterion is given insufficient attention. The reason for this may be the fact that the distress of the parents against the background of the child's injury may not reach the level of clinical diagnosis, or the fact that it is customary to pay more attention to the needs of the child than the family as a whole. nine0108 22 Service staff should pay more attention to the fact that the consequences of trauma can have a more serious impact on the family system as a whole.

Parental distress is a significant factor influencing post-traumatic reactions in children. However, in medical institutions this criterion is given insufficient attention. The reason for this may be the fact that the distress of the parents against the background of the child's injury may not reach the level of clinical diagnosis, or the fact that it is customary to pay more attention to the needs of the child than the family as a whole. nine0108 22 Service staff should pay more attention to the fact that the consequences of trauma can have a more serious impact on the family system as a whole.

Literature

- Scheeringa, M., et al., New findings on alternative criteria for PTSD in preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 2003. 42(5): p. 561-570.

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (4th edition, Text Revision). nine0119 2000, Washington, DC: Author.

- Scheeringa, M.S., et al., Two approaches to the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder in infancy and early childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 1995. 34(2): p. 191-200.

- Scheeringa, M.S., C.H. Zeanah, and J.A. Cohen, PTSD in Children and Adolescents: Toward an Empirically Based Algorithm. Depression and Anxiety , 2011. 28(9): p. 770-782.

- De Young, A.C., J.A. Kenardy, and V.E. Cobham, Diagnosis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Preschool Children. nine0118 Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology , 2011. 40(3): p. 375-384.

- Meiser-Stedman, R., et al., The posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis in preschool- and elementary school-age children exposed to motor vehicle accidents. American Journal of Psychiatry , 2008. 165(10): p. 1326-1337.

- Stoddard, F.J., et al., Acute stress symptoms in young children with burns. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 2006.

45(1): p. 87-93.

45(1): p. 87-93. - De Young, A.C., et al., Prevalence, comorbidity and course of trauma reactions in young burn-injured children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 2012. 53(1): p. 56-63.

- Scheeringa, M.S., et al., Factors affecting the diagnosis and prediction of PTSD symptomatology in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry , 2006. 163(4): p. 644-651.

- Graf, A., C. Schiestl, and M.A. Landolt, Posttraumatic Stress and Behavior Problems in Infants and Toddlers With Burns. nine0118 Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2011. 36(8): p. 923-931.

- Levendosky, A.A., et al., Trauma symptoms in preschool-age children exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence , 2002. 17(2): p. 150-164.

- Scheeringa, M.S., et al., Predictive validity in a prospective follow-up of PTSD in preschool children. J ournal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 2005.

44(9): p. 899-906.

44(9): p. 899-906. - Le Brocque, R.M., J. Hendrikz, and J.A. Kenardy, The Course of Posttraumatic Stress in Children: Examination of Recovery Trajectories Following Traumatic Injury. nine0118 Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2010. 35(6): p. 637-645.

- Carpenter, G.L. and A.M. Stacks, Developmental effects of exposure to Intimate Partner Violence in early childhood: A review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review , 2009. 31(8): p. 831-839.

- Carrion, V.G., C.F. Weems, and A.L. Reiss, Stress predicts brain changes in children: A pilot longitudinal study on youth stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, and the hippocampus. nine0118 Pediatrics , 2007. 119(3): p. 509-516.

- Perry, B.D., et al., Childhood trauma, the neurobiology of adaptation, and ''use-dependent'' development of the brain: How ''states'' become ''traits''. Infant Mental Health Journal , 1995. 16(4): p. 271-291.

- Green, J.G., et al.

, Childhood Adversities and Adult Psychiatric Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I Associations With First Onset of DSM-IV Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry , 2010. 67(2): p. 113-123.

, Childhood Adversities and Adult Psychiatric Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I Associations With First Onset of DSM-IV Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry , 2010. 67(2): p. 113-123. - Felitti, V.J., et al., Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults - The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 1998. 14(4): p. 245-258.

- De Young, A.C., Psychological impact of burn injury on young children and their parents: Implications for diagnosis, assessment and treatment (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation), 2011, School of Psychology, University of Queensland: Brisbane. nine0034

- Landolt, M.A., et al., The mutual prospective influence of child and parental post-traumatic stress symptoms in pediatric patients. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 2012. 53(7): p. 767-774.

- Hall, E., et al.

, Posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of children with acute burns. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2006. 31(4): p. 403-412.

, Posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of children with acute burns. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2006. 31(4): p. 403-412. - Le Brocque, R.M., J. Hendrikz, and J.A. Kenardy, Parental response to child injury: Examination of parental posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories following child accidental injury. nine0118 Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2010. 35(6): p. 646-655.

- Lieberman, A.F., Traumatic stress and quality of attachment: Reality and internalization in disorders of infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal , 2004. 25(4): p. 336-351.

- Scheeringa, M.S. and C.H. Zeanah, A relational perspective on PTSD in early childhood. Journal of Traumatic Stress , 2001. 14(4): p. 799-815.

- Nugent, N.R., et al., Parental posttraumatic stress symptoms as a moderator of child's acute biological response and subsequent posttraumatic stress symptoms in pediatric injury patients. nine0118 Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2007.

32(3): p. 309-318.

32(3): p. 309-318. - Kazak, A.E., et al., An integrative model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2006. 31(4): p. 343-355.

- Roberts, N.P., et al., Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Multiple-Session Early Interventions Following Traumatic Events. American Journal of Psychiatry , 2009. 166(3): p. 293-301.

- Kenardy, J., et al., Information-provision intervention for children and their parents following pediatric accidental injury. nine0118 European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 2008. 17(5): p. 316-325.

- Cox, C.M., J.A. Kenardy, and J.K. Hendrikz, A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Web-Based Early Intervention for Children and their Parents Following Unintentional Injury. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 2010. 35(6): p. 581-592.

- Zehnder, D., M. Meuli, and M.A. Landolt, Effectiveness of a single-session early psychological intervention for children after road traffic accidents: a randomized controlled trial.

nine0118 Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health , 2010. 4: p. 7.

nine0118 Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health , 2010. 4: p. 7. - Berkowitz, S.J., C.S. Stover, and S.R. Marans, The Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention: Secondary prevention for youth at risk of developing PTSD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 2011. 52(6): p. 676-685.

- Scheeringa, M.S., et al., Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: a randomized clinical trial. nine0118 Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 2011. 52(8): p. 853-860.

- Melnyk, B.M., et al., Creating opportunities for parent empowerment: Program effects on the mental health/coping outcomes of critically ill young children and their mothers. Pediatrics , 2004. 113(6): p. E597-E607.

- Kramer, D.N. and M.A. Landolt, Characteristics and efficacy of early psychological interventions in children and adolescents after single trauma: a meta-analysis.