Denial in a relationship

My partner is in denial

Being in denial is a psychological defence mechanism against acknowledging “uncomfortable truths” in your relationship. Either you or your partner might be in denial, as a way of coping with difficult circumstances by hiding from your problems – such as avoiding responsibility for your part in conflict, addressing destructive patterns of behaviour or contributing to a communication breakdown. Despite the problems being self-evident, you may find it easier to overlook them, rather than confront each other head-on.

For example, you may be in denial as a couple about how you deal with problems such as a lack of intimacy, poor communication and constant arguments. You may be all too aware of the issues, but avoid taking action to resolve things. Rather than talking through your concerns with your partner, you carry on regardless. It just seems too painful or embarrassing to bring things out in the open without descending into outright confrontation.

You may even mask your emotions behind a veneer of politeness and compliance – pleasing people and sacrificing your own needs, rather than communicating how you really feel. Instead of asserting your needs, you may isolate yourself and withdraw from contact, because you fear being judged or rejected by the people you love. Or perhaps you’re worried about revealing hidden flaws and vulnerabilities in your character, so you hide behind the safety of a false persona - fulfilling your role as a wife, partner, parent, carer or provider, rather than being your true self. Slowly your sense of identity erodes away until you feel lost and unappreciated. It may happen to both people, but you seem unwilling to acknowledge the problem.

A strategy of denial may also apply to the person you live with. Perhaps you recall a time when you’ve challenged your partner about a problem, which they deny all knowledge of, despite it being common knowledge. So being in denial can be very frustrating for both parties and reinforces a strategy of avoidant behaviour. Refusing to accept reality, is often used as a defensive reaction - excusing or a justifying behaviours that you have disowned or feel ashamed of. Even guilty about.

Refusing to accept reality, is often used as a defensive reaction - excusing or a justifying behaviours that you have disowned or feel ashamed of. Even guilty about.

Being in denial may form a mutual pattern of withholding emotions and reinforcing defensive behaviours. You both start glossing over the facts, rather than facing up to them. These behaviours are often expressed by avoiding owning up to things or omitting telling the truth in order to avoid conflict. Sometimes even using a direct lie, because the truth seems too painful to confront. And each time you try you feel thwarted or dismissed by your loved one. You might feel your partner is hiding something, because of a change in behaviour, but feel unable to bring it up in case you’re accused of being paranoid. Or you fear rocking the boat and provoking yet another argument.

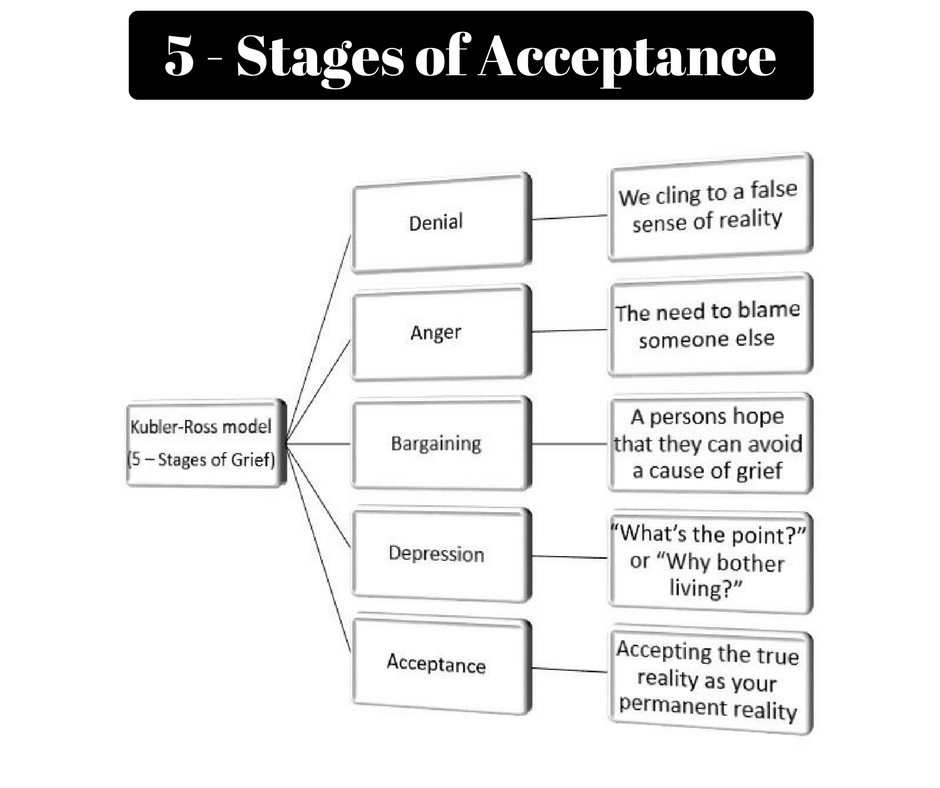

Being in denial is a survival strategy

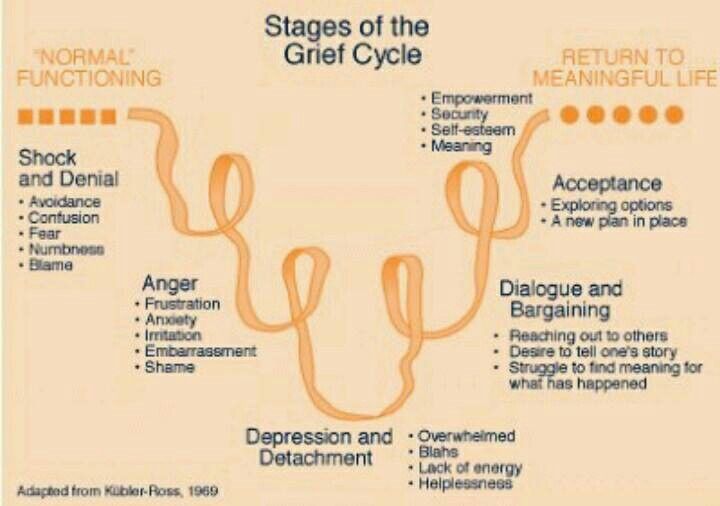

All human beings are in denial to some extent. They need to be as a matter of survival, so they’re not continually overwhelmed by the decisions they make in a crisis. Otherwise,, humans might not respond effectively to stressful situations. For example, denying the potential risks to life and limb, in order to survive in a threatening environment. Being in denial can also be a matter of psychic survival after a devastating loss or trauma. Such as when a woman is going through grief after the death of her husband and still sets the table for him at breakfast because she cannot bear to accept his absence.

Otherwise,, humans might not respond effectively to stressful situations. For example, denying the potential risks to life and limb, in order to survive in a threatening environment. Being in denial can also be a matter of psychic survival after a devastating loss or trauma. Such as when a woman is going through grief after the death of her husband and still sets the table for him at breakfast because she cannot bear to accept his absence.

Lower down the scale you can go into denial as part of a strategy in intimate relationships so that you don’t have to face up to things you feel ashamed of, or want to avoid worrying about. You probably recall an incident in your own life, where you put a lid on things, or pushed aside your suspicions in order to continue in blissful ignorance. Perhaps you decided to overlook evidence that your partner was having an affair to preserve the peace; protecting yourself from a nagging sense of impending doom. But by refusing to acknowledge your fears, you have stored up trouble for later on.

For example, you may deny feeling anxious when your partner spends a long time away from home, because you feel abandoned and find it difficult to manage your feelings. And yet you deny it, on their return; harbouring resentment, shutting down and distancing yourself from your emotional contact. You might punish your partner with the silent treatment. Not wanting to reveal the hidden flaw in your character or the guilty secret about feelings of ‘separation anxiety’. So you pretend to have no knowledge of these things and bury them deep down in your subconscious.

Different strategies of being in denial

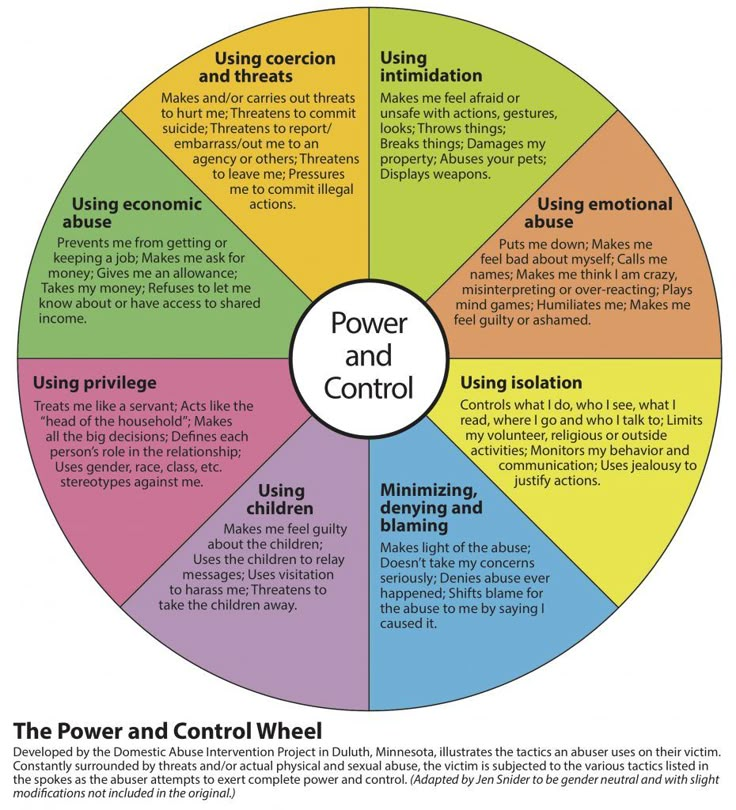

Denial can be a conscious strategy for coping with feelings of helplessness and a fear of failure in relationships. You may avoid taking responsibility for your mistakes – such as when you deny abusive behaviour and blame it on provocation by your partner. Or make excuses for your behaviour as if it were out of your control. At other times when intimacy is beginning to fade in a relationship, it may be hard for both of you to take the painful decision to end it, so you postpone the decision for as long as possible. Both of you collude in this deception, rather than face up to the facts.

Both of you collude in this deception, rather than face up to the facts.

At other times, being in denial can be an unconscious defence mechanism, where you’re unaware of the psychic conflict between repressed feelings and your conscious rationalisation of them. You say one thing, but feel another. Your partner may also have got used to editing his or her memory of a recent conflict, by denying it ever happened, in order to make life more tolerable. This follows defensive patterns of behaviour learned in childhood, as a survival strategy to protect themselves from the shame of showing vulnerability, or voicing their fears to parents who were emotionally unavailable.

Why go into denial?

So why is it so easy for couples to fall into a spiral of self-deception and denial? Why do couples tend to ignore the existence of uncomfortable truths in their relationships even when it’s an open secret?

It seems far easier for couples who fear ending the relationship than being alone, to develop a strong psychological defence against recognising their problems.

Some psychological studies have shown a psychological bias that clouds people’s ability to detect lies once they fall in love and become emotionally attached. The euphoria of falling in love creates a heady mix of hormones (oxytocin and dopamine) which allow people to ignore the early warning signs of their partner’s flaws and inadequacies. But it isn’t until the harsh reality of long-term monogamy, which bring these issues to the surface that people begin to pay attention. What couples have overlooked for so long – such as a lack of intimacy, trust or empathy, can quickly turn into resentment and neglect. Either way, couples need to work at changing their patterns of behaviour or continue as the same vicious cycles are being played out in their relationship.

The prevalence of denial and self-deception are also common in relationships where infidelity, co-dependency and abuse are happening. But why do people put up with this? Why do they imagine things will change if they carry on like before? Or pretend that an abusive partner will change once they save them from themselves, when this is precisely what enables the worst kind of behaviours.

As anyone who has invested in abusive relationships can testify, they do not tend to follow a rational pattern of behaviour. Nor do relationships have to be fulfilling or improve people’s sense of well-being in order to remain intact. They are often held together by manipulation, emotional blackmail and dependency, whether people are willing to admit this or not.

One may describe a list of characteristics in an ideal relationship, but after close inspection, their relationships do not match up to the ideal. They are more likely to be based on learned helplessness, fragile egos and vulnerability, than love and security.

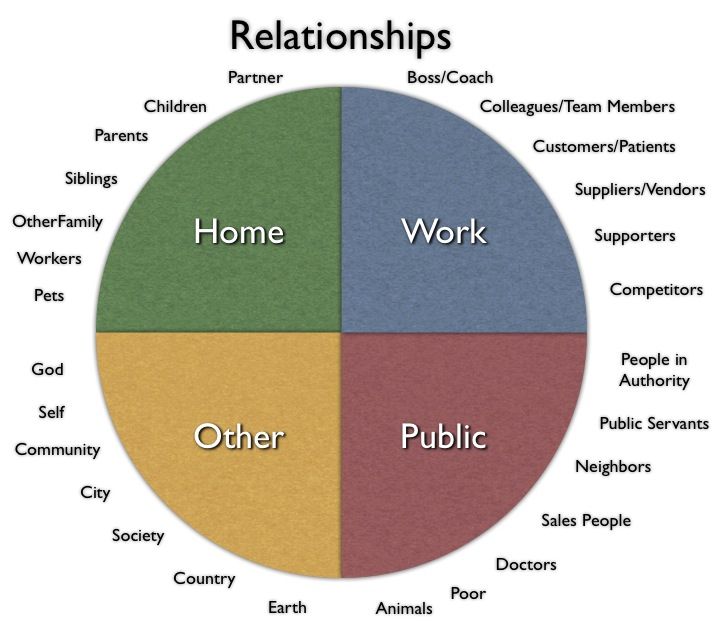

Relationships can be heavily influenced by the way couples depend on each other for the roles they play and the transactions they engage in. For example, someone who only feels loved and valued by looking after the needs of others, may find themselves in codependent relationships where a partner relies on them to enable their drug dependency, alcoholism or learned helplessness. This creates a transactional relationship between a rescuer/carer and victim so that both partners collude with dependency in the name of ‘unconditional love’, which it isn’t. It’s exploitation.

This creates a transactional relationship between a rescuer/carer and victim so that both partners collude with dependency in the name of ‘unconditional love’, which it isn’t. It’s exploitation.

To preserve our craving for attachment and avoid the fear of being abandoned, we often tolerate the trap of co-dependency. We may even be compliant with controlling and abusive partners, because we falsely believe our love, loyalty and commitment will help them change one day. We hold onto false hopes and fantasies in order to distort our vision of what is actually happening in a relationship. And protect ourselves from the truth. The conscious mind sees and believes what it wants to believe. And it buries the truth in the subconscious. If there is any contradiction between the two, it is split off from the conscious mind in the form of denial.

Remarkably, it is because attachments create stability, that the downside is this: your drive towards attachment and emotional contact, is less concerned with how fulfilled or content you are in relationships and more concerned that you remain together. The drive towards attachment may supersede your own needs, your mental health and your long-term happiness or independence. All in the name of “love”.

The drive towards attachment may supersede your own needs, your mental health and your long-term happiness or independence. All in the name of “love”.

It is only by escaping the trap of denial and self-deception, that you have any chance of breaking the cycles of codependence to find yourself. This is what couples counselling is for: re-setting relationships and creating healthier boundaries so that each person can flourish and evolve. As well as learning to be honest and open in your communication; not remain in denial.

Breaking out of denial means owning up to your anxieties about change and experimenting with new ways of behaving. Accepting your need to negotiate boundaries and respecting each other’s private space and individual differences. Then re-adjusting your expectations to a shared set of values. Developing healthier patterns of behaviour and communication can be risky as well as anxiety provoking. It means to be willing to change yourself, not demand change from the other person first.

Look for the early warning signs of denial and self-deception in yourself - which can range from ignoring feelings of suspicion, excusing your partner’s behaviour and contradicting your gut-instinct. This includes making exceptions that compromise your basic needs, by rationalizing the situation so you can justify your partner’s behaviour.

In the past, this may have included not asking questions when there is clear evidence of your partner’s infidelity. Or excusing violence and abuse, by blaming yourself for provoking your partner. Making exceptions, by telling yourself that your partner’s erratic behaviour and mood swings are a ‘one-off’ when they form part of a pattern. Or telling yourself it’s your duty to sacrifice your needs, by offering unconditional love at your own expense. And compromising for less when you receive very little in return.

Change lies within you. Because your suspicions aren’t absolute evidence they should prompt you to ask questions of yourself first and investigate further – such as asking yourself whether you’ve developed an emotional block, or an unconscious defence against accepting painful truths about your own behaviour. You need to gain deeper insight into how you have contributed to this process, not constantly seek to change the other person.

You need to gain deeper insight into how you have contributed to this process, not constantly seek to change the other person.

You need to take a reality check and look at the evidence. Share your findings and concerns with your partner. Challenge them about what you believe if you have credible evidence that the issues are being ignored. Listen to their feedback and whether they seem honest and open to acknowledging the problems, or whether they’re defensive and attempt to close down any discussion. You may come to an agreement to change the habitual patterns of behaviour you have come to depend on, in order to make small changes and learn how to develop healthier ways of relating.

You may seek a trusted confidante; someone who can listen and provide you with objective feedback; helping you disentangle your emotions and collect your thoughts. But you need to talk with someone who won’t let their personal agenda prejudice yours.

Be true to yourself by acknowledging the reality about your relationship. All you have is your gut instinct as you can never know the truth with absolute certainty. Each person has their own version of the truth. But be prepared. This process can be emotionally painful, but it’s better than hiding behind the mask of denial. There’s no point maintaining the pretence that everything’s okay, while under the surface you’re in breakdown. You need to acknowledge and validate your feelings, not live in fear, or continually contradict yourself with self-doubt. You need to satisfy your intuition, while eliciting the emotional support of friends and family.

All you have is your gut instinct as you can never know the truth with absolute certainty. Each person has their own version of the truth. But be prepared. This process can be emotionally painful, but it’s better than hiding behind the mask of denial. There’s no point maintaining the pretence that everything’s okay, while under the surface you’re in breakdown. You need to acknowledge and validate your feelings, not live in fear, or continually contradict yourself with self-doubt. You need to satisfy your intuition, while eliciting the emotional support of friends and family.

Gaining insight in couples therapy can be an independent and powerful way of helping you identify the problems more clearly and discussing your blind spots without fear of being manipulated. It can lead to greater self-awareness and healing as you confront uncomfortable truths in your relationships. Despite the difficulties there is an opportunity for change and growth once the grip of denial has been broken. Even hope.

Even hope.

Are You in Denial? | What Is Codependency?

We’re all in denial. We’d barely get through the day if we worried that we or people we love could die today. Life is unpredictable, and denial helps us cope and focus on what we must in order to survive. On the other hand, denial harms us when we ignore problems for which there are solutions or deny feelings and needs. However, if you’re in denial, you won’t know it. Learn how to recognize denial in all its forms.

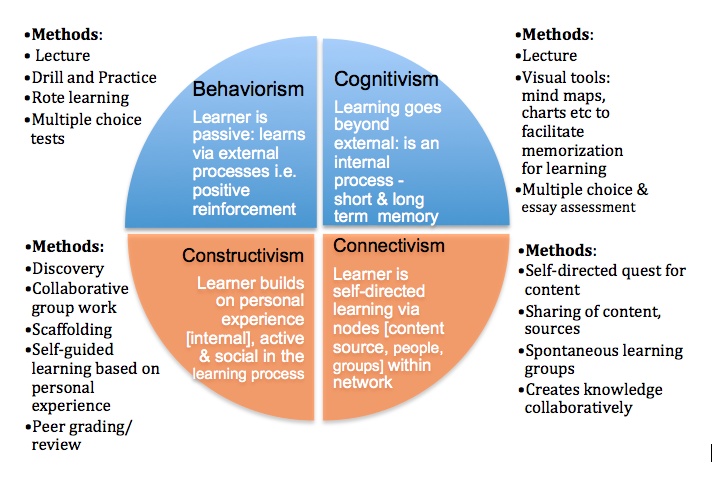

Types and Degrees of Denial

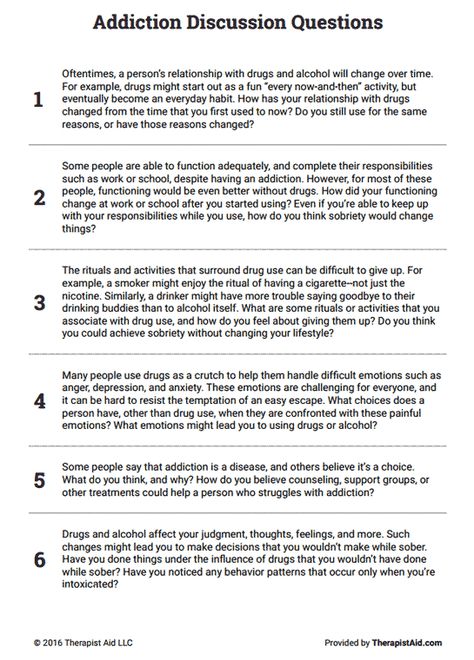

When it comes to codependency, denial has been called the hallmark of addiction. It’s true not only for drug (including alcohol) addicts, but also for their partners and family members. This axiom also applies to abuse and other types of addiction. We may use denial in varying degrees.

- First degree: Denial that the problem, symptom, feeling or need exists.

- Second degree: Minimization or rationalization about it.

- Third degree: Admitting it, but denying the consequences.

- Fourth degree: Unwilling to seek help for it.

Thus, denial doesn’t always mean we don’t see there’s a problem, we might rationalize, excuse, or minimize its significance or effect upon us. Other types of denial are forgetting, outright lying or contradicting the facts due to self-deception. Deeper still, we may repress things that are too painful to remember or think about.

Reasons for Denial

Denial is a defense that helps us. There are many reasons we use denial, including avoidance of physical or emotional pain, fear, shame or conflict. We’re actually wired to deny for survival. It’s the first defense that we learn as a child. I thought it cute when my four-year-old son vehemently denied having eaten any chocolate ice cream, while the evidence was smeared all over his mouth. He had lied out of self-preservation and the fear of being punished.

Difficult emotions

Denial is adaptive when it helps us cope with difficult emotions, such as in the initial stages of grief following the loss of a loved one, particularly if the separation or death is sudden. Denial allows our body-mind to adjust to the shock more gradually.

Denial allows our body-mind to adjust to the shock more gradually.

It’s not adaptive when we deny warning signs of a treatable illness or problem out of fear. Many women delay getting mammograms or biopsies out of fear, even though early intervention leads to greater success in treating cancer. Applying the various degrees, above, we might deny that we have a lump; next rationalize that it’s probably a cyst; third, admit that it could be or actually is cancer, but deny that it could lead to death; or admit all of the above and still be unwilling to get treatment.

Inner conflict

Another major reason for denial is inner conflict. Children often repress memories of abuse not only due to their pain, but because they’re dependent on their parents, love them, and are powerless to leave home. Young children idealize their parents. It’s easier to forget, rationalize, or make excuses than accept the unthinkable reality that my mother or father (their entire world) is cruel or crazy. Instead, they blame themselves.

Instead, they blame themselves.

As adults, we deny the truth when it might mean we’d have to take action we don’t want to. We might not look at how much debt we’ve accumulated, because that would require us to lower our spending or standard of living, creating inner conflict.

A wife rationalizes facts that suggest her husband is cheating and supplies other explanations. Confronting the truth forces her to face not only the pain of betrayal, humiliation, and loss, but the possibility of divorce. An addicted parent might look the other way when his child is getting high, because he’d have to do something about his own marijuana habit.

Frequently, partners of addicts or abusers are on the “merry-go-round” of denial. Addicts and abusers can be loving and even responsible at times and promise to stop their drug use or abuse, but soon it returns breaking trust and promises. Once again apologies and promises are made and believed because the partner loves them, may deny his or her own needs and worth, and is afraid to end the relationship.

Familiarity

Another reason we deny problems is because they’re familiar. We grew up with them and don’t see that something is wrong. So if we were emotionally abused as a child, we wouldn’t consider mistreatment by our spouse to be abuse. If we were molested, we might not notice or protect our child from being incested. This is first-degree denial.

We might acknowledge that our spouse is verbally abusive, but minimize or rationalize. One woman told me that even though her husband was verbally abusive, she knew he loved her. Most victims of abuse experience third-degree denial, meaning that they don’t realize the detrimental impact the abuse is having on them – often leading to PTSD long after they’ve left the abuser. If they faced the truth, they’d be more likely to seek help.

Shame and trauma

Codependents have internalized shame from childhood, as described in my book, Conquering Shame and Codependency. Shame is an extremely painful emotion. Most people, including myself for many years, don’t realize how much shame drives their lives – even if they think their self-esteem is pretty good. Needs and feelings are often “shame-bonded” in childhood if they were ignored or shamed. We may deny a shame-bonded feeling, such as fear or anger, minimize or rationalize it, or be unaware of how much it’s affecting us.

Needs and feelings are often “shame-bonded” in childhood if they were ignored or shamed. We may deny a shame-bonded feeling, such as fear or anger, minimize or rationalize it, or be unaware of how much it’s affecting us.

Denial of needs is a major reason codependents remain unhappy in relationships. They deny problems and deny that they’re not getting their needs met. They’re not aware that that’s the case. If they do, they might feel guilty and lack the courage to ask for what they need or know how to get their need met. Learning to identify and express our feelings and needs is a major part of recovery and is essential to wellbeing and enjoying satisfying relationships.

How to Know if You’re in Denial

You might be wondering how to tell if you’re in denial. There are actually signs. I’ve mentioned some, including rationalization, making excuses, forgetting, and minimization. If you’re in a relationship with a drug user or drinker, does your partner’s behavior affect his or her job, family and social obligations, or your relationship? Here are more. Do you:

Do you:

- Think about how you wish things would be in your relationship?

- Wonder, “If only, he (or she) would . . .?”

- Doubt or dismiss your feelings?

- Believe repeated broken assurances?

- Conceal embarrassing aspects of your relationship?

- Hope things will improve when something happens (e.g., a vacation, moving, or getting married)?

- Make concessions and placate, hoping it will change someone else?

- Feel resentful or used by your partner?

- Spend years waiting for your relationship to improve or someone to change?

- Walk on egg-shells, worry about your partner’s whereabouts, or dread talking about problems?

If you answered yes to any of these questions, uncover how you may have been trained to deny and tips for what you can do. Read more about denial and codependency in Codependency for Dummies and join a 12-Step program. A professional therapist can assist your recovery by pointing out your defenses, questioning contradictions between your thoughts and reality, helping you identify denied feelings and needs, and supporting you in facing your fears and inner conflicts and in making changes.

Like any illness, the stages of codependency and addiction worsen without treatment, but there is hope and people do recover to lead happier, more fulfilling lives.

©Darlene Lancer 2014

Share with friends

5 Ways to Deal with Rejection and Become Stronger

46,207

Man among men Practices how to

Rejection itself means that right now our expectations have not been met. Each person can count many situations in which he was refused: someone was not given a visa, someone did not get his favorite job, and someone heard “no” from a loved one.

But you can react to this fact in different ways. Some give up and lower their bar. Others try again, with renewed vigor. What can be learned from the latter?

1. Quantity becomes quality

Gallup polls show that, on average, each smoker makes more than three attempts to quit smoking. Every attempt, even a failed one, is a new experience.

Each time we get to know ourselves a little more, our capabilities and limitations. It’s the same with failure: whatever your goal, you have to go through a phase of failure in order to achieve sustainable results.

In order to get a new job, we will have to hear the phrase “You are not quite right for us” several times in a row. To find a partner - an offer to remain friends, a short "no" or even a puzzled look. Do not get hung up on experiences, think that every failure brings you closer to your cherished goal.

Inventor Alexander Bell once said very accurately: “When one door closes, another opens. And we often look at the closed door with such greedy attention that we do not notice at all those that are open to us.

2. Rejections (like failures) make us more attractive in the eyes of others

Oddly enough, a history of failure can play into our hands. Psychologist Elliot Aronson came to this conclusion back in 1966. He observed the behavior of the spectators, who evaluated the two participants in the intellectual competition.

The first was confident and answered most of the questions correctly, the second was confused and generally made an unconvincing impression.

At some point, one of the players spilled coffee on himself. If a loser did it, the audience didn't sympathize with him. But if a competent player made a mistake, they sympathized with him even more: now he seemed more “earthly” and humane.

Your failures are what keeps you alive. Consistent success generates distrust, but failure creates a sense of drama and empathy. Treat them with humor, make fascinating stories out of them - this way you will make them work for you.

3. Refusal is the prerogative of free people

The inability to say “no” is a sign of self-doubt. Low self-esteem prevents us from feeling our worth and forces us to turn to other people in order to “earn” the right to exist.

On the contrary, refusal is the free choice of a person who knows his worth. The ability to accept refusal is the flip side of the ability to refuse.

4. Look for constructive meaning

Sometimes we are rejected directly and rudely. But sometimes rejection can contain grains of life wisdom. The main thing is to see them. Remember that refusal is always more honest than consent given under pressure or out of a desire to maintain good relations.

5. The hardest thing is not rejection, but waiting

Most often, it is uncertainty that causes anxiety and feelings of impotence. We count the hours and minutes as we wait for a letter, a phone call, or a knock on the door.

Anxiety grows, causing us to imagine worst-case scenarios. In such a situation, any answer becomes a relief: at least the lingering silence is broken, and you can move on.

Remember, failure is part of real life. It only means that the door is closed. Instead of banging your head against it or crying at its doorstep, you can go in search of another - open.

Text: Anton Soldatov Photo source: Getty Images

New on the site

“My sister died in childbirth, and my mother cursed me. Why? I don't want a child”

Why? I don't want a child”

“The father-in-law doesn't help our family in the slightest. All the attention goes to their youngest son”

Canadian scientists have discovered a simple way to strengthen marriage

“I want a lot from my future partner”: a reader’s confession and a psychoanalyst’s comment

Is it possible to kill in a dream: a psychiatrist — about typical and rare sleep disorders

Pain is so sweet!.. How modern authors describe abuse: analysis with examples

Quiz: Do you have a fear of rejection?

Sexualization of robots from the game Atomic Heart: is it dangerous - the opinion of a psychologist

why it is so difficult to be rejected by a person

Psychologist Guy Winch has some practical tips to help mitigate the negative impact of rejection.

Rejection is the most common type of emotional upheaval we experience in our daily lives. More recently, the risk of being rejected was very insignificant, since it was limited to the person’s immediate social circle or his search in dating clubs. Today, thanks to electronic communications, social networks and various dating applications, each of us is connected with thousands of people, and any of them can ignore our posts, chats, notes or profiles in dating services, which makes us feel rejected. .

Today, thanks to electronic communications, social networks and various dating applications, each of us is connected with thousands of people, and any of them can ignore our posts, chats, notes or profiles in dating services, which makes us feel rejected. .

In addition to these minor failures, we are also subject to serious and more destructive failures. The pain of a rejected person - someone who has been abandoned by a spouse, fired from a job, who has been turned away by friends, or who, due to this or that lifestyle, is not accepted by either relatives or society, can be truly paralyzing.

Psychology of refusal

Whether you have experienced rejected love or some other kind of emotional upheaval, major or minor rejection, one thing remains the same - it is always a very painful experience, and usually more unpleasant than we expect.

And the question is why? Why do we get so upset if a close friend didn't "like" a photo we posted on Facebook from a family holiday? Why can this ruin the mood completely? Why, because of something seemingly so insignificant, can we get angry with a friend, upset? Even our self-esteem is reduced at such moments.

The main damage from refusal is usually caused by ourselves. When our self-esteem is badly hurt, we go and destroy it even more.

It's simple - our brain is programmed to react in this way. By examining the brains of people who were asked to remember the last time they were rejected using a functional magnetic resonance therapy machine, scientists came to surprising conclusions. When we experience rejection, the same areas of the brain are activated as when we experience physical pain. That is why even a trifling rejection is more painful than we think, because it literally hurts (way and on an emotional level).

But why is our brain programmed this way?

Evolutionary psychologists believe that this mechanism goes back to the era of hunter-gatherer tribes. Since then a person could not survive alone, being rejected by society was actually a death sentence. As a result, we developed an early warning mechanism about the danger of “being expelled from the tribe” - and this was a refusal. Fear of rejection contributed to survival. Those who took the rejection more painfully most often changed their line of behavior, remained in the tribe and had the opportunity to continue their lineage.

Fear of rejection contributed to survival. Those who took the rejection more painfully most often changed their line of behavior, remained in the tribe and had the opportunity to continue their lineage.

Of course, emotional pain is just one of the effects of rejection on our well-being. In addition, rejection also damages mood and self-esteem, triggers anger and aggression, and undermines our need to “be a part of something.”

Unfortunately, most of the damage from rejection is usually done by ourselves. And it’s true, if you were dumped by the partner you were dating, or if you were the last to be selected in the team gathering, the natural reaction is not to accept the rejection, we will not go to lick our wounds, no, we become extremely self-critical. We berate ourselves, lament our shortcomings, and even feel disgusted with ourselves. In other words, when our self-esteem is very hurt, we go and make things worse. This pattern of behavior harms our emotional health and is also psychologically self-destructive, but despite this, all of us have done it at some point.

But, fortunately, there are better, more sensible ways to respond to rejection, algorithms to follow to avoid unhealthy responses to such situations, techniques to alleviate emotional pain and restore self-esteem. Here are some of them.

No self-criticism

No matter how much you want to list all your shortcomings after receiving a refusal, and no matter how logical it would be to punish yourself for what you did “wrong” - it’s not worth it! Armed with all possible means, try to review what happened and determine for the future what could be done differently, but remember: there is not the slightest reason to be self-critical and strict with yourself in this situation. How to survive the rejection of a man or a girl? It’s okay to think, “Maybe the next first date shouldn’t bring up my ex,” but “What a loser I am!” - No.

Another common mistake we make is taking rejection personally when it isn't. Most rejections, whether in romantic or business relationships or in the social sphere, are a matter of “taste” and chance. Exhausting yourself by looking for your own shortcomings in an attempt to understand why it “didn’t work” is not only unnecessary - it’s not far from false conclusions.

Exhausting yourself by looking for your own shortcomings in an attempt to understand why it “didn’t work” is not only unnecessary - it’s not far from false conclusions.

Restoring self-esteem

When self-esteem is hit, it's important to remind yourself what you have to offer (instead of listing your shortcomings). Psychologically, the best way to increase self-esteem for an outcast person is to emphasize their significant characteristics. Make a list of five important, meaningful qualities that make you a great potential relationship partner (for example, you are always ready to help and support emotionally), a good friend (for example, you are a loyal person and a good listener), or a reliable employee (for example, you responsible or accustomed to strictly adhere to labor discipline). Then choose one of them and write a paragraph or two (write, not just think) about why this quality is important to others and how it can be manifested in the appropriate situation. By giving yourself this kind of first aid, you will boost your self-esteem, ease the emotional turmoil, and gain the confidence to move on.