Definition pragmatic language

Definition, Symptoms, What to Do- Cadey

What is Pragmatic Language in Childhood?

Pragmatic language in childhood is social language. These skills include polite greetings, sharing information, asking questions of others, and engaging with them in conversation.

In typical child development, children learn to communicate with others somewhat naturally. Children learn to chat back and forth about a topic. They show delight in each other’s ideas with facial expressions and body language. They share information, ask questions of one another, and read nonverbal communication cues from peers.

For some children with a pragmatic language disorder or impairment, these skills do not develop naturally. Pragmatic language therapy may be essential for a child to develop these skills when they are less automatic.

Want immediate help? Ask a question on HelpMe Cadey, our free AI-infused way to get you recommendations fast.

Symptoms of Pragmatic Language Issues in Children

Some children may speak very well but seem unable to talk to friends. They may enjoy facts and details and love books about insects or outer space, but they may express little interest in socializing. They may not seem to read facial expressions or nonverbal cues, and they may struggle to make inferences from what friends share. Instead, they may only take information verbatim or in a concrete manner. Here are some common signs and symptoms of pragmatic language issues.

- Social difficulties: child does not understand how to interact with peers in conversation, read communicative intent, or follow along in conversation

- Vulnerable to teasing: child has difficulty understanding the motives of peers; may be taken advantage of often or be overly sensitive to sarcasm or jokes

- Often confused: child seems confused when talking with peers; does not follow back-and-forth conversations

- Quiet around peers: child has trouble joining peers in conversation.

They may speak to adults just fine but seem very shy around peers.

They may speak to adults just fine but seem very shy around peers. - Formal vocabulary: child may sound too mature for their age. They may use big words like “it’s preposterous,” “I’m confounded,” or “propagating the species”

- Non-verbal communication issues: child misses important feedback from peers in terms of body language and eye contact; may talk too long on a topic without noticing others are bored

- Monologues: child talks on and on without allowing others to get a word in; conversations lack the back-and-forth quality

Recognizing pragmatic language challenges

A child psychologist’s clinical evaluation or a speech-language pathologist’s speech evaluation may lead to the discovery of pragmatic language challenges. It is helpful to discover this information early because so much can be done through language therapy and practice at home.

Listed below are some signs you may notice of pragmatic language issues.

…You hear “I don’t know” or “I don’t remember” a lot. When you ask your child to tell you about their day, you may see a blank stare. You may also notice that your child has challenges telling you how they feel about things. This difficulty relates to something called ‘insight’ which is the ability to recognize and talk about one’s emotions.

…Your child may do much better on structured tasks. For example, your child may enjoy the organization and consistency of the school day. They may thrive on seated schoolwork activities. However, they may sit alone during recess. They may have trouble with free play, creative social interaction, and social problem-solving. You may even see behavior problems in these unstructured times because your child is unsure how to act and react socially.

…You hear your child report that the other kids are mean. Although it is certainly possible that the other kids are being unkind to your child, keep an eye on statements like these. It could be that your child is really having trouble connecting with other kids.

It could be that your child is really having trouble connecting with other kids.

All of the above are signs that your child may be struggling with pragmatic skills. Listed below are some of the pragmatic language milestones we expect kids to reach at various ages. If concerns are noted, there are suggestions in this article to help your child work on these critical skills.

Phases of Pragmatic Language Development in Childhood

In terms of pragmatic language development, it is important to ensure that your child’s skills are on track with peers their age. A typical trajectory for pragmatic development would look as follows (Linder & Peterson-Smith, 2008, p.264-269) [1]:

Pragmatic skill progression in infants, toddlers, and preschool children

- 2 months: eye contact

- 3 months: social smile

- 4 months: vocalizes to initiate socializing, social laugh

- 5 months: shows a preference for familiar faces

- 6 months: refuses objects or toys they don’t want

- 7 months: plays simple games like peek-a-boo

- 8 months: follows the pointing and eye gaze of caregiver

- 9 months: makes requests and initiates interactions

- 10 months: initiates games, points to desired objects

- 11 months: uses gestures and simple words to get another’s attention

- 12 months: shared enjoyment, takes turns

- 15 months: shared joint attention, follows directions to look at something

- 18 months: responds to simple requests for clarification such as, ‘what?’ or ‘huh’?

- 24 months: takes one or two turns in a conversation

- 36 months: uses words to communicate in play, engages in some parallel play but may also interact with peers by sharing toys or commenting on their play

If your baby, toddler, or preschooler’s skills are not developing as shown in the list above, there may be concerns about pragmatic language skills. Keep in mind that pragmatic language skills build on each other over time. As you will see below, communication gets more complex as the child matures.

Keep in mind that pragmatic language skills build on each other over time. As you will see below, communication gets more complex as the child matures.

Pragmatic skill progression in older children

Kindergarten social skills require play skills and language abilities. Once children reach elementary school, the skills should evolve. You would want your kindergarten child to play games with peers, such as a card game like Uno or a board game like Jenga. You would expect them to play tag on the playground using some back-and-forth social language to establish the rules. Children this age read one another’s emotions on faces and know when and how to enter games and join other children.

In 1st grade to 2nd grade, social skills get more advanced. As children move up in elementary school, we expect them to understand jokes and sarcasm. They will now be able to discern whether or not they should take statements literally. For example, we would expect a 2nd grader to know that ‘button your lip’ means being quiet, not actually buttoning your lip.

In 3rd grade to 5th grade, relationships become more complex. In the later years of elementary school, kids have established deeper and longer-lasting friendships. Those relationships require lots of social communication. Conversations now include inside jokes, gentle teasing, sharing and keeping secrets, and telling stories.

In middle school and high school, intimate relationships develop. Teens and pre-teens have even higher expectations in terms of pragmatic social skills. They need to learn how to ‘read the room’ to know if their voice should be loud or soft. Teens are expected to understand how different people like to communicate. Some friends joke around while others might be more serious.

They also need to pick up on non-verbal communication skills, such as another child in their midst suddenly becoming quiet. This quiet demeanor may indicate that the peer has hurt feelings or is confused. A teenager with good social communication skills can pick up and respond to these subtle social cues in conversations.

As shown here, pragmatic language skills build on each other throughout childhood. It is a good idea for you to watch to see if your child’s skills are coming along typically. If there are concerns, this article can provide some ideas and next steps to advance your child’s skills.

Top 10 Causes of Pragmatic Language Issues in Children

Clinically, social communication is called pragmatic language. Pragmatic language refers to the social aspects of speech, such as conversation, reading nonverbal cues, and maintaining a back-and-forth flow of information. If your child is struggling, here are some of the potential causes of these challenges.

Cause #1: Poor perspective-taking

Perspective-taking is the ability to understand and relate to another person’s thoughts, interests, and ideas. It requires noticing when a peer is disinterested by reading nonverbal cues. Signs of disinterest might include: shifting eye contact, appearing squirmy, or drifting off during conversation.

To have quality reciprocal conversations, an individual must be able to do the following:

- think of relevant things to share

- draw on experiences

- pay attention

- take turns

- formulate questions

- know when and how to end the conversation politely

Cause #2: Immature social development

Social communication is much more complex than vocabulary. Even very bright individuals can have difficulties with pragmatic communication. In that case, speech therapy is often required to get along with peers, do well in school, and support long-term success and happiness.

The primary reason your child may struggle with social communication is that these skills simply don’t come naturally. For most individuals, social development follows a typical course from the early childhood play skills, to the BFFs in 3rd grade, and on into high school and adulthood, where relationships deepen.

For some children, this ‘natural’ progression does not happen. Instead, the child struggles to make friends and socialize with peers. There are many reasons why this can occur, and it can certainly be the case in supportive, loving homes. Parents, listen closely! It is not your fault! Some kids simply socialize naturally, and some kids simply don’t. For those who don’t, there is a lot of help available.

Cause #3: Social cognition problems

Social ‘cognition’ refers to understanding social relationships and social interactions. This skill includes picking up on social cues and comprehending social language, such as idioms, sarcasm, and humor.

If your child is struggling with the cognition of these important and nuanced social skills, interpersonal interactions will likely feel confusing and frustrating. Often, direct teaching of these skills can help a child with challenges in social cognition learn to pick up social cues and interact with others more effectively.

Cause #4: Developmental delays

Certainly, some typically developing children may struggle socially from time-to-time. However, if your child has consistent issues with social skills, a developmental disability may be present. It also could be an issue called ‘developmental delay,’ which means what the name implies. That is, the child is simply not meeting developmental milestones as expected.

Cause #5: Developmental disabilities

Challenges with pragmatic language issues are often related to a developmental disability. The child may qualify for a diagnosis of autism, anxiety, or ADHD. A relatively new disorder could explain these challenges, called Social Pragmatic Communication Disorder. This is a somewhat new term in the manual psychologists use to diagnose. The term is closely related to autism but without the restricted and repetitive behaviors or sensory difficulties.

Cause #6: Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism includes challenges in social communication and restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior or interests. Social communication challenges in autism often include difficulty with both verbal and nonverbal communication, back-and-forth conversations, and listening skills.

Social communication challenges in autism often include difficulty with both verbal and nonverbal communication, back-and-forth conversations, and listening skills.

Many individuals with autism speak very well and have a huge vocabulary. They may use formal language, recall detailed information, and converse frequently with peers. Conversations that veer off-topic or miss the point are common for autism.

For example, if a peer is sharing an emotional story about her dog dying, an autistic child may ask, “what breed was it?” or say, “oh, that’s the life cycle” instead of saying, “I’m so sorry, that is sad.” This example serves to show how the social language and perspective-taking may be challenging for some autistic individuals.

Cause #7: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

ADHD can cause pragmatic language challenges because of the interplay of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. People with ADHD are often ‘disinhibited’ which means it is hard for them to resist doing the first thing that pops in their heads.

A child with ADHD may cut a peer off, invade personal space, forget what is being discussed, or talk on and on without listening. All of these behaviors could have an impact on social interactions. However, many individuals with ADHD do not have any social challenges. Social skills issues are not diagnostic for ADHD but sometimes ADHD symptoms can interfere with social interactions.

Cause #8: Social anxiety

A child with social anxiety may have issues with pragmatics. The anxiety your child feels could make it hard to think of what to say, leading to short answers, extreme shyness, and social avoidance. Anxiety could cause challenges with planning or working memory. It can be hard for children to read social cues if they are not thinking clearly.

Cause #9: New culture or language

A child who moves to an unfamiliar place may struggle socially for a while. This may be especially true if your child is learning a new language. It can be hard to pick up on some social cues, jokes, sarcasm and other nuances, when a child is assimilating into a new culture. This is not at all a sign of a language disorder. Most kids with strong social skills in one culture will eventually make new friends and feel comfortable in a new place. It will be important for family and friends to be supportive and patient with this process.

This is not at all a sign of a language disorder. Most kids with strong social skills in one culture will eventually make new friends and feel comfortable in a new place. It will be important for family and friends to be supportive and patient with this process.

Cause #10: Quirky kiddo

Some children really can only enjoy certain types of people, prefer being alone a lot, or have mild social anxiety in specific situations. They may avoid big parties, loud concerts, or assemblies. Perhaps you have a quirky kid with peculiar interests and a unique interaction style. If your child is happy and healthy, these social patterns are fine! Research shows that most people do just fine with one good friend and one close relationship at home. No matter how quirky your child is, there has to be one other kid who is just as quirky and needs a friend just as much. Help your child make connections with others and do not stress if your child prefers the company of just one or two friends instead of having several.

There’s good news! Children can be taught social communication skills. To improve pragmatic language, a parent can access a lot of strategies and resources listed below.

First, use and model social and emotional language for your child. Talk about your feelings, and share about your day and how you cope. “Work was stressful for mom today, so I’m going to take a walk. Would you like to come too?”

Second, get your child enrolled in social activities that are low-risk socially. Good options are Lego club, cooking class, robotics club, and music. Find an activity with a team or group that isn’t extremely competitive. Start with something that has a structure but is about individual performance. Pay attention to who the coach or adult sponsor is, and seek those individuals who are accepting, warm, and not competitive.

Third, practice social conversation with your child, and provide feedback like, “you could ask Sally what she did this weekend. ” Provide a bit of structure to family discussions instead of simply asking, “how was your day?” Instead of asking a broad question, you can help your child think of a better response by asking, “How did it go with that art project you have been working on in class?” Listen carefully and do not give up when your child can’t think of anything to say. It takes practice and this practice begins to pay off over time.

” Provide a bit of structure to family discussions instead of simply asking, “how was your day?” Instead of asking a broad question, you can help your child think of a better response by asking, “How did it go with that art project you have been working on in class?” Listen carefully and do not give up when your child can’t think of anything to say. It takes practice and this practice begins to pay off over time.

Fourth, provide breaks and downtime. Give your child time to relax after school. Most kids will want time to decompress after school. Perhaps allow your child to play a bit or have some fun at the park before launching into a discussion about the day. When you do start talking, you can give very specific prompts like, “what did you have for lunch” or “what game did you play in P.E?”

Fifth, seek out structured social groups. If your child continues to struggle, seek out a social group, social skills therapy and supports at your child’s school. We have seen children make significant gains in pragmatic language skills with practice.

We have seen children make significant gains in pragmatic language skills with practice.

When to Seek Help for Pragmatic Language Challenges

The biggest sign that it is time to seek help is when your child constantly struggles to make friends. You may notice your child is confused or frustrated frequently during social interactions. It is a good idea to seek help if you see one of these challenges occurring for your child.

- Your child may say they have lots of friends but may not be able to tell you much about them

- Your child may know their friends’ heights and eye color but may not recall what they like to do for fun

- Your child may report that everyone in class is mean or that they just don’t like anyone

- Your child may boss other kids around or lecture on a topic without stopping to assess whether anyone is listening

- Your child never asks how others are doing or struggles to carry on a back-and-forth conversation

If any of the above challenges are happening fairly frequently, it would be good to seek help. Many school-based and community-based speech therapists treat pragmatic language, and it is generally readily amenable to intervention.

Many school-based and community-based speech therapists treat pragmatic language, and it is generally readily amenable to intervention.

Further Resources on Pragmatic Language

- Psychologist or neuropsychologist: to consider pragmatic symptoms in a developmental context, a comprehensive evaluation could include social skills and language evaluation as well as a look at verbal and nonverbal abilities as well as problem-solving skills

- School psychologist: to test IQ or intelligence, anxiety, social skills and consider the academic impact

- Speech and language pathologist: to provide language assessment and then therapy, at-school therapy can happen at lunchtime or during recess for a natural social environment. This therapy may be in a group, or the therapist may come into the classroom to facilitate social learning

- Social group: to work on social communication.

Often facilitated by a social worker, counselor, or psychologist, a group with other children with an emphasis on social and conversation skills can help. Make sure your child is matched by approximate age and children have similar language skills and ideally some peer models as well

Often facilitated by a social worker, counselor, or psychologist, a group with other children with an emphasis on social and conversation skills can help. Make sure your child is matched by approximate age and children have similar language skills and ideally some peer models as well

Similar Conditions to Pragmatic Language Problems

- Social skills: children with poor pragmatic language are likely to have overall social skill difficulties

- Social anxiety: children with poor pragmatic skills may be very nervous in social situations

- General anxiety: children with poor pragmatic skills may have anxiety

- Expressive language: children with poor pragmatic skills may not be able to express their thoughts and ideas due to a language problem

- Receptive language: children with poor pragmatic skills may have difficulty understanding what others are saying

- Attention problem: children with poor attention skills may have trouble with pragmatic language due to the tendency to miss social cues and not listen during social interactions

- Hyperactivity: children with poor pragmatics who are hyperactive may not be able to communicate socially due to excessive movement

- Conversation: children with poor pragmatic skills are likely to struggle with conversations

References on Pragmatic Language In Childhood

[1] Linder Ed. D., Toni & Petersen-Smith Ph.D., Ann (2008) Administration Guide for TPBA2 & TPBI2 (Play-Based Tpba, Tpbi, Tpbc).

D., Toni & Petersen-Smith Ph.D., Ann (2008) Administration Guide for TPBA2 & TPBI2 (Play-Based Tpba, Tpbi, Tpbc).

Book Resources on Pragmatic Language In Childhood

Jed Baker’s series of books for social skills and behavioral supports. He specializes in ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Link: www.jedbaker.com

Barton, Erin E. & Harn, Beth (2012). Educating Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Sage.

Kroncke, Willard, & Huckabee (2016). Assessment of autism spectrum disorder: Critical issues in clinical forensic and school settings. Springer, San Francisco.

Philofsky, A., Fidler, D. J., & Hepburn, S. (2007). Pragmatic Language Profiles of School-Age Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders and Williams Syndrome. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(4), 368-380. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2007/040)

Social Skills, Social Communication and Pragmatic Language

September 3, 2019

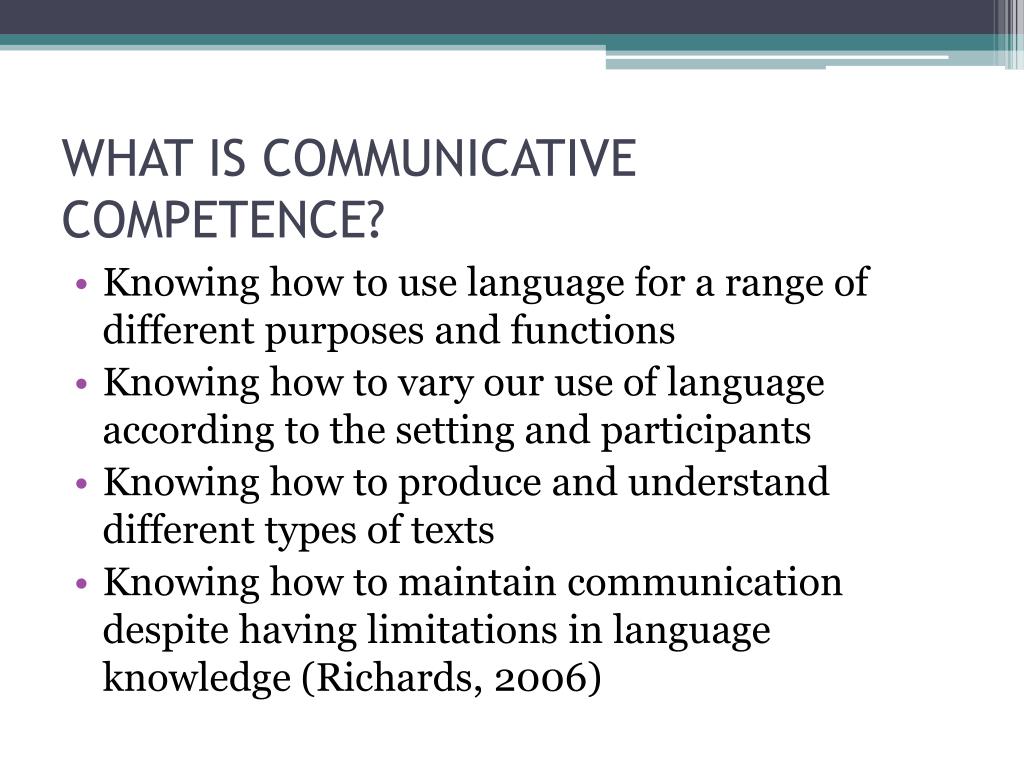

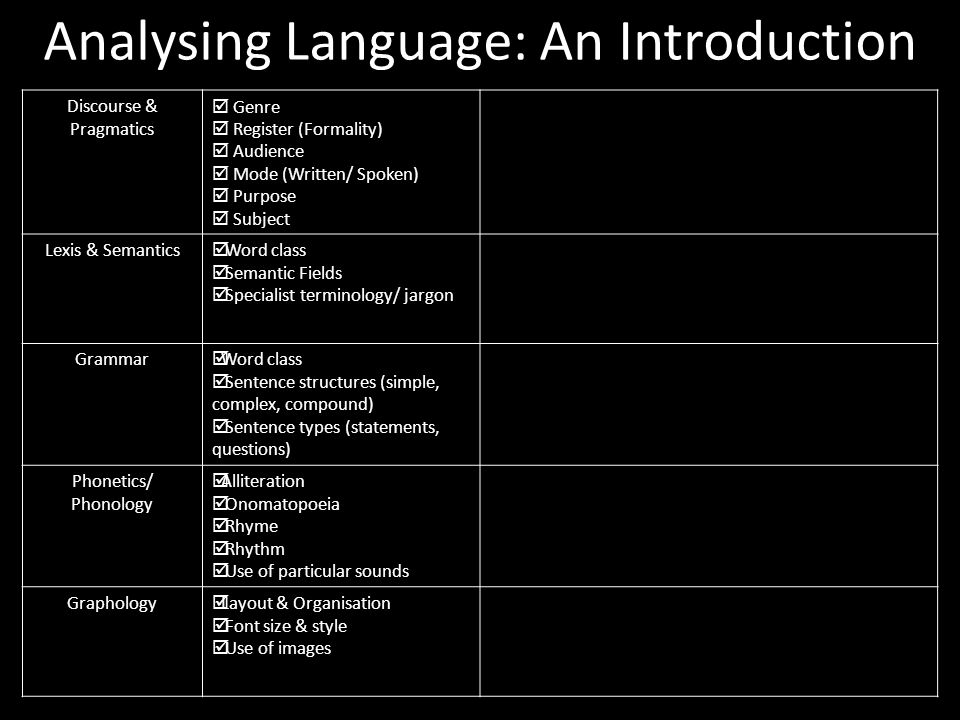

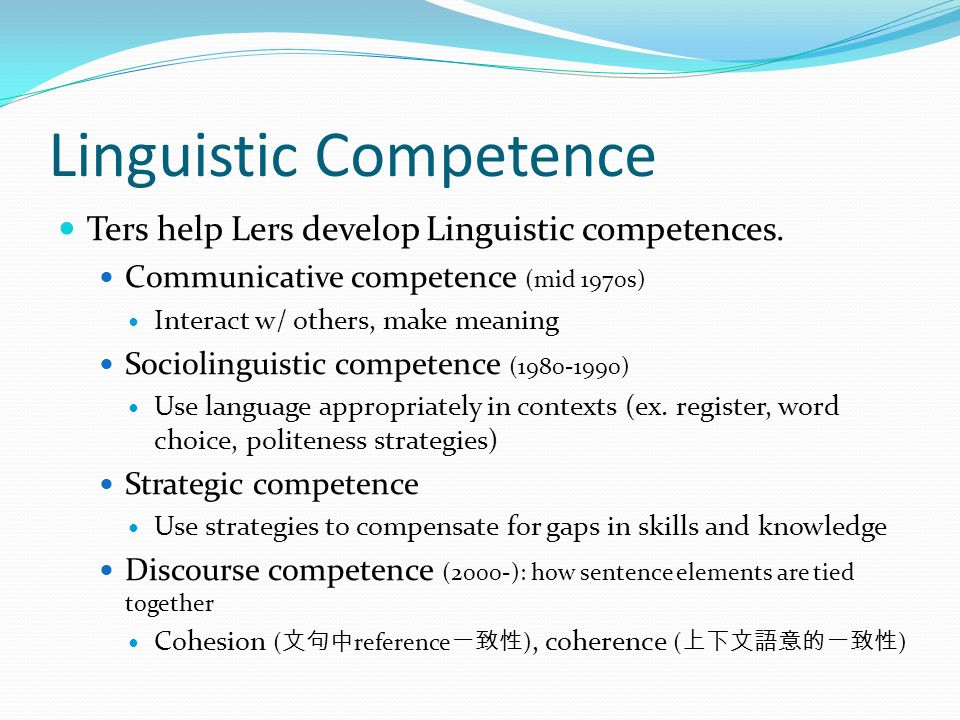

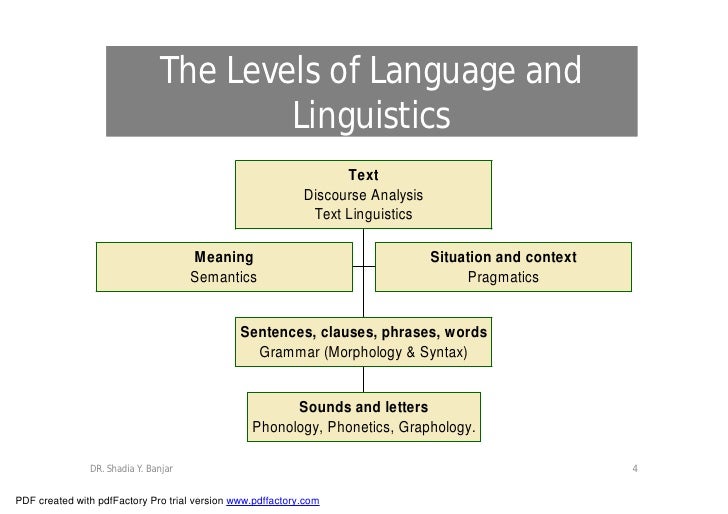

What is the difference between social skills, social communication skills and social pragmatics? These terms are closely related and often used interchangeably. The term used may vary depending on the type of professional talking about them, such as a doctor, speech-language pathologist, psychologist or teacher.

The term used may vary depending on the type of professional talking about them, such as a doctor, speech-language pathologist, psychologist or teacher.

Social Skills allow us to interact with others clearly and effectively in a social situation. We use social skills when we notice social cues in the people around us. In addition, we think about what others are doing and what their reactions might mean. Also, having strong social skills means knowing how to interact positively with other people. The article What Are Social Skills? from Psychology today is a good resource.

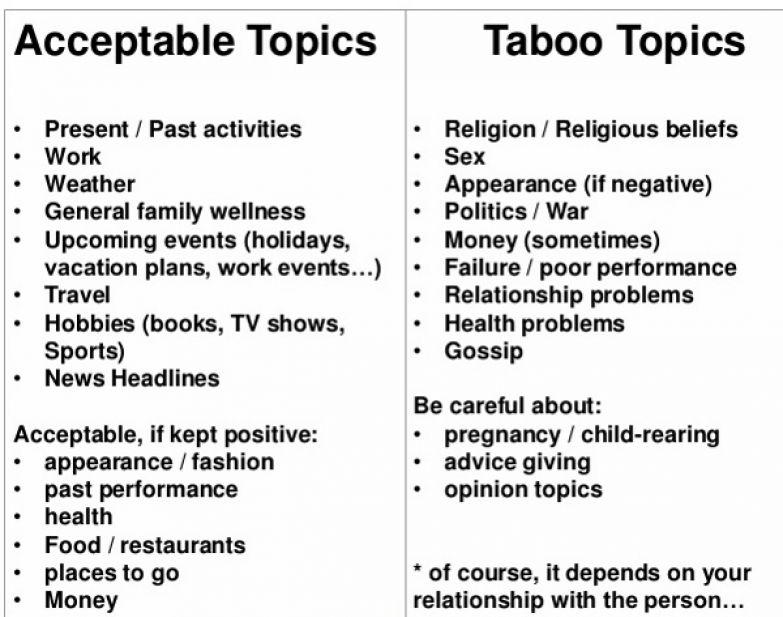

Social Communication Skills are a vital part of the human experience, allowing individuals to communicate and bond with one another. This includes the ability to change the language you use depending on who you are talking to. For example, talking differently to a friend versus an adult, or giving more information to someone who does not know the topic, and knowing to skip some details when someone already knows the topic. Social communication skills also includes following the rules of a conversation such as:

Social communication skills also includes following the rules of a conversation such as:

- taking turns when talking

- staying on topic

- gestures

- body language

- understanding personal space

- facial expressions

- eye contact

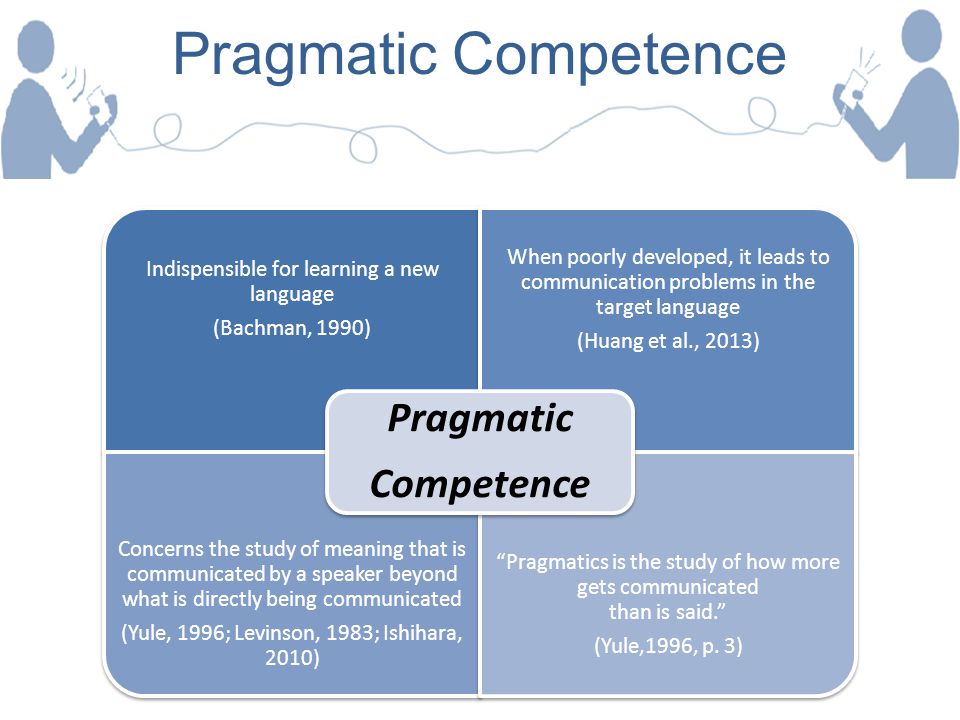

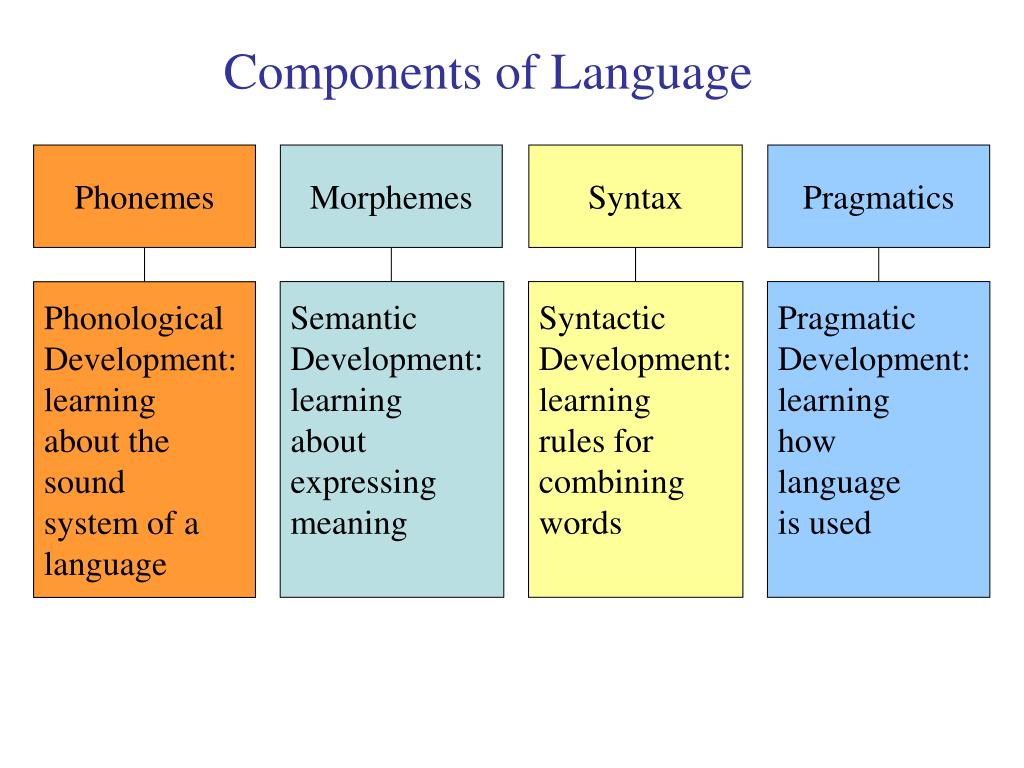

Pragmatic Language consists of the social language skills that we use in our daily interactions with others. This includes conversational skills, the use of our non-verbal communication skills, understanding non-literal language, problem solving, interpreting and expressing emotions. People with pragmatic language disorders typically have a difficult time expressing and managing themselves appropriately in social situations.

The Center for Development and Learning states that “…children with verbal and nonverbal communication difficulties often resort to temper tantrums or ‘meltdowns’ to communicate emotions such as anger and frustration. They may appear uncooperative, fresh or rude and may be called oppositional and/or defiant. Helping these children improve their communication skills can greatly improve their social skills and level of peer acceptance.” Research has shown that, “…positive peer interactions in childhood set the stage for the formation of friendships that serve as primary socialization experiences for children.” (Hadley & Schuele, 1998)

Helping these children improve their communication skills can greatly improve their social skills and level of peer acceptance.” Research has shown that, “…positive peer interactions in childhood set the stage for the formation of friendships that serve as primary socialization experiences for children.” (Hadley & Schuele, 1998)

Does your child have a difficult time interacting with their friends or classmates? Do they have a hard time sharing or engaging in back and forth conversation? Do they make off-topic remarks, or struggle with reading body language and understanding personal space? If so, then an evaluation may be helpful. Social skills and pragmatic language can be evaluated by a psychologist or a speech-language pathologist.

Following an assessment, goals are developed to address the individual needs of the client. Depending on the problems identified, recommended interventions may include speech-language pathology, counseling, occupational therapy, social skills group or therapeutic summer camp participation. These treatments increase successful use of important skills needed every day. This includes learning how to greet others, engage in back and forth conversations, ask for help, manage emotions, and recognize and understand the emotions of others.

These treatments increase successful use of important skills needed every day. This includes learning how to greet others, engage in back and forth conversations, ask for help, manage emotions, and recognize and understand the emotions of others.

The goal of treatment is to increase social acceptance with “…intervention efforts that focus on peer-related social competence addressing two distinct but interrelated needs: (a) maximizing children’s abilities to function effectively and appropriately in real-life, peer contexts and (b) minimizing potential barriers to participation in the mainstream resulting from negative social judgments.” (Hadley & Schuele, 1998) Treatment is beneficial for children who aren’t developing social skills as quickly as their peers. This may include children with ADHD, who can be too active and physical in their play with peers. It may include children with nonverbal learning disabilities or autism, who may have trouble picking up on social cues. Children with social communication challenges, developmental delays, and other types of learning or behavior issues may also benefit from intervention.

Social skills groups have been offered at New Horizons Wellness Services for several years. Starting this fall, Peer Speech Therapy will also be offered. Peer Speech Therapy is a treatment session led by a speech-language pathologist targeting the individual needs and pragmatic language goals for children in a small group setting. The goal is to facilitate success and generalization of skills. Peer Speech Therapy will allow children to practice their skills in a more realistic social setting. This will help them use the skills learned beyond the therapy clinic. Research has shown that it is important for speech-language pathologists to target socially relevant language objectives with children who have difficulty with language “Because these children eventually must live up to standard societal expectations in social, educational, and vocational settings. (Hadley & Schuele, 1998) Peer Speech Therapy provides the opportunity for children to learn and practice appropriate social skills needed to confidently interact with the world around them.

Looking for more information? Here is a list of past blogs about social skills:

- Teaching Friendship Skills

- Sharing – An Important Social Skill!

- Giving Advice – An Important Social Skill

- Improving Your Child’s Social Skills: Making Eye Contact

- Social Skills Group Overview

- Social Skills for Children with ASD

References:

ASHA – Social Communication. Retrieved from https://www.asha.org/public/speech/development/Social-Communication

Hadley, P. A., & Schuele, C. M. (1998). Facilitating Peer Interaction. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 7(4), 25–36. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360.0704.25

Social Skills And School. Retrieved from https://www.cdl.org/articles/social-skills-and-schoo

Yours in Health,

New Horizons Wellness Services13333 SW 68th Pkwy,

Tigard, OR 97223

- https://g.page/newhws

New Horizons Wellness Services provides a true multidisciplinary approach to mental & physical health treatments for children, adults and families.

Topic 3. Pragmatic aspects of communication

1. Pragmatic factor in communication

2. Social norms

3. Issues and tasks

4. Recommended literature

Appendix I. Pragmatic context in the literary text

adjacent concepts adjacent

background knowledge

presuppositions

social norms

situational context

interpreter

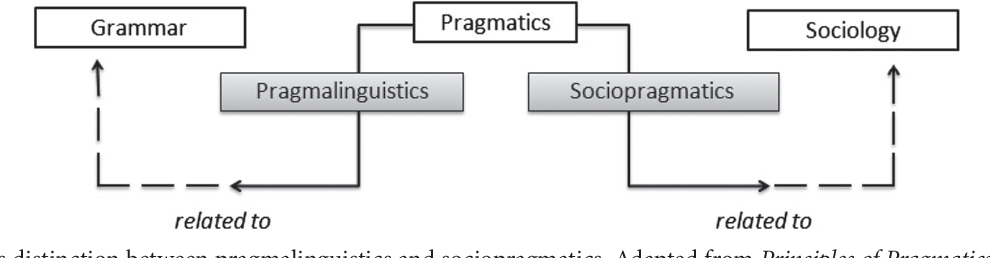

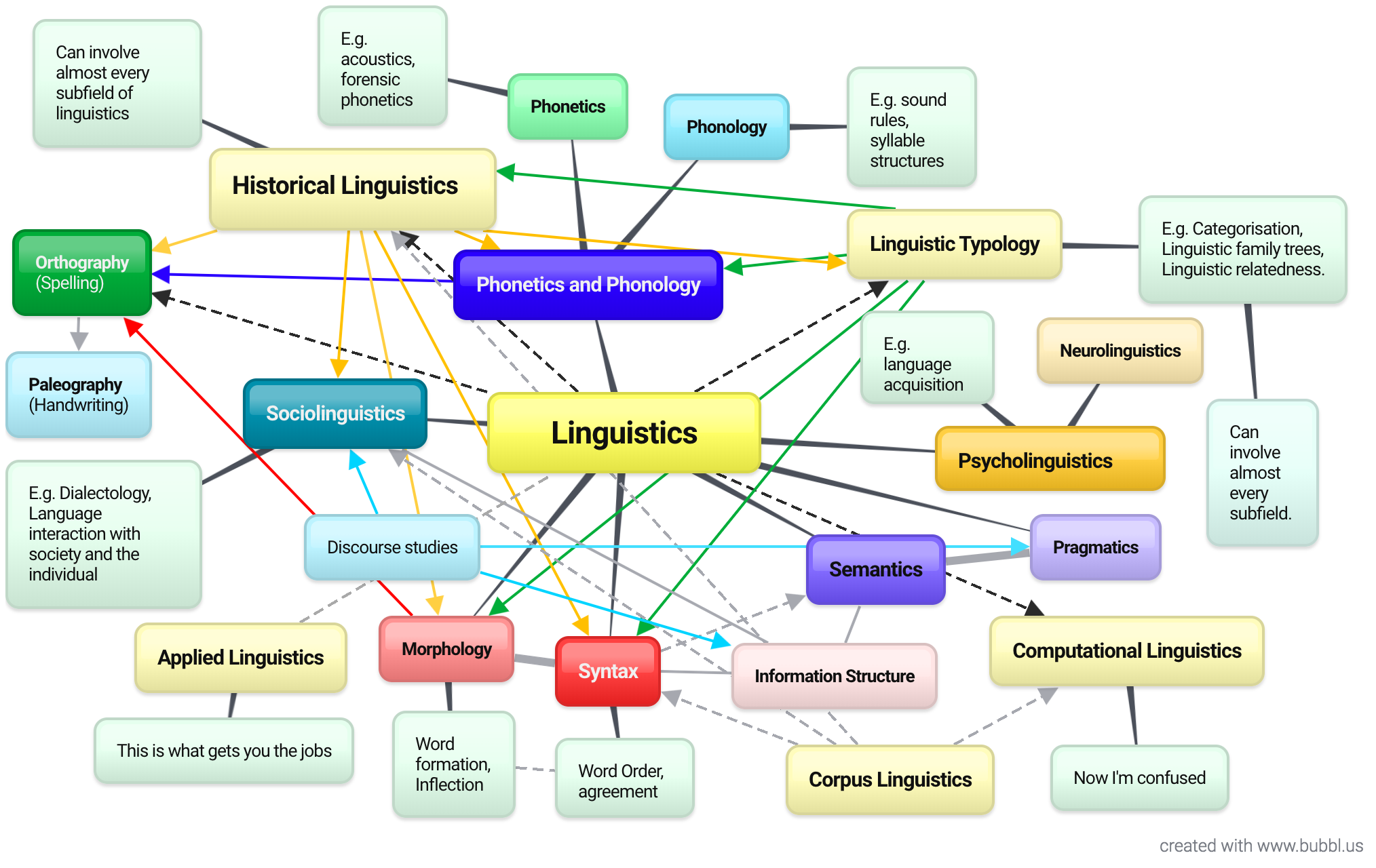

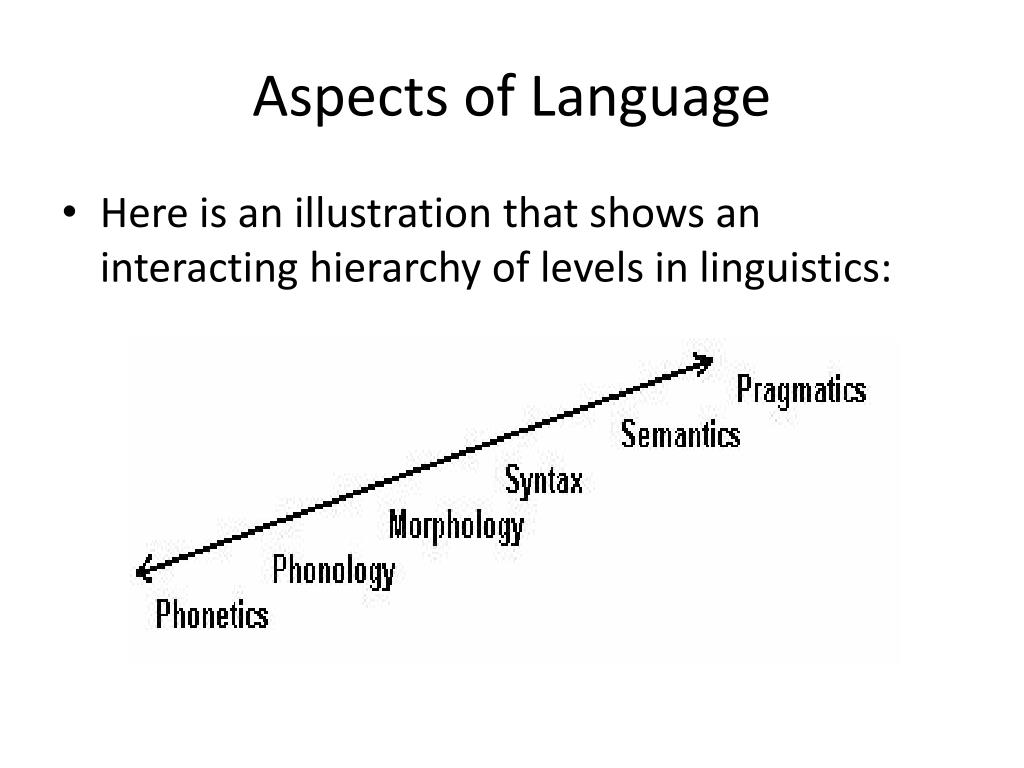

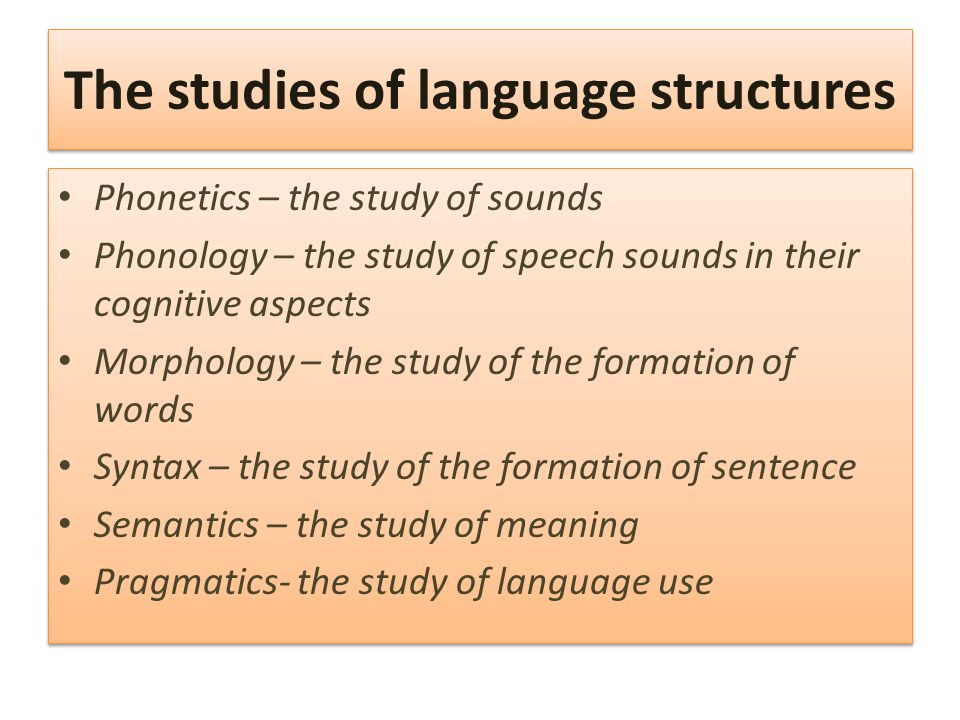

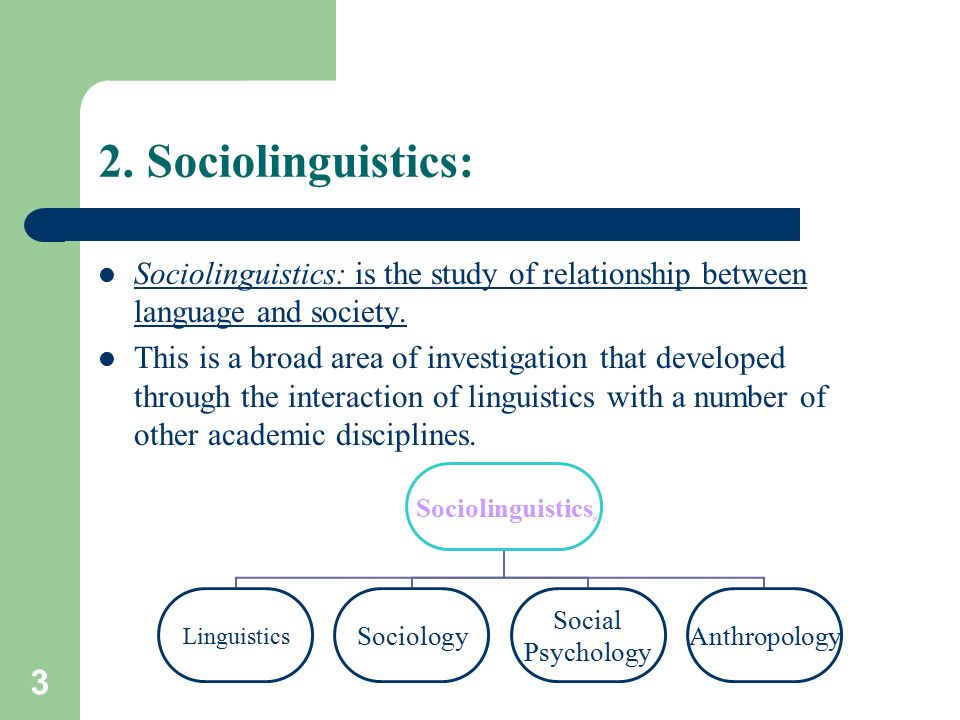

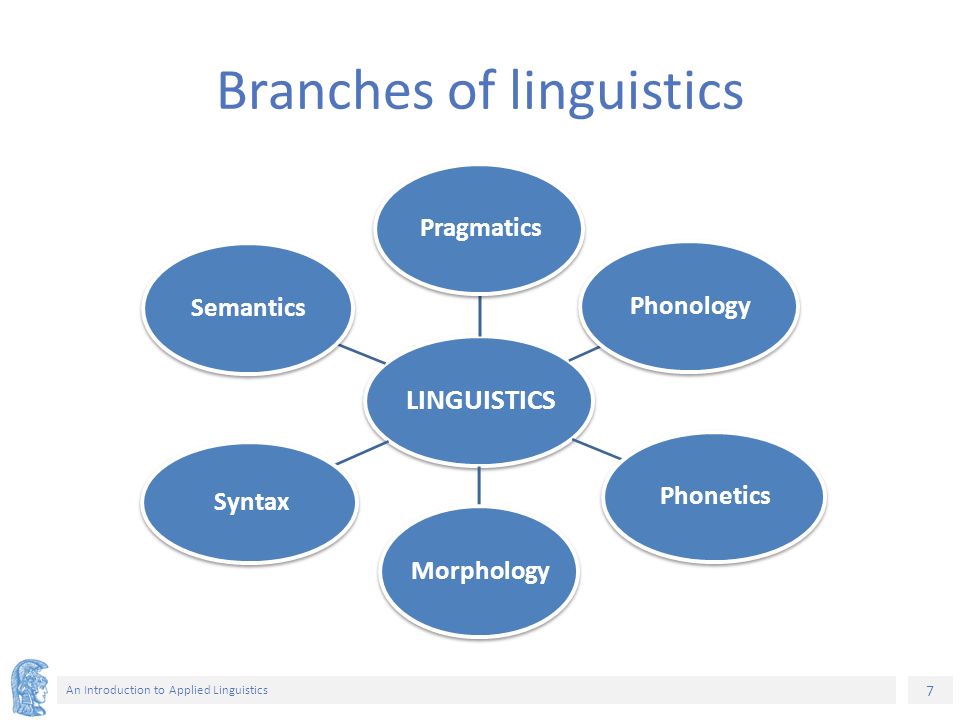

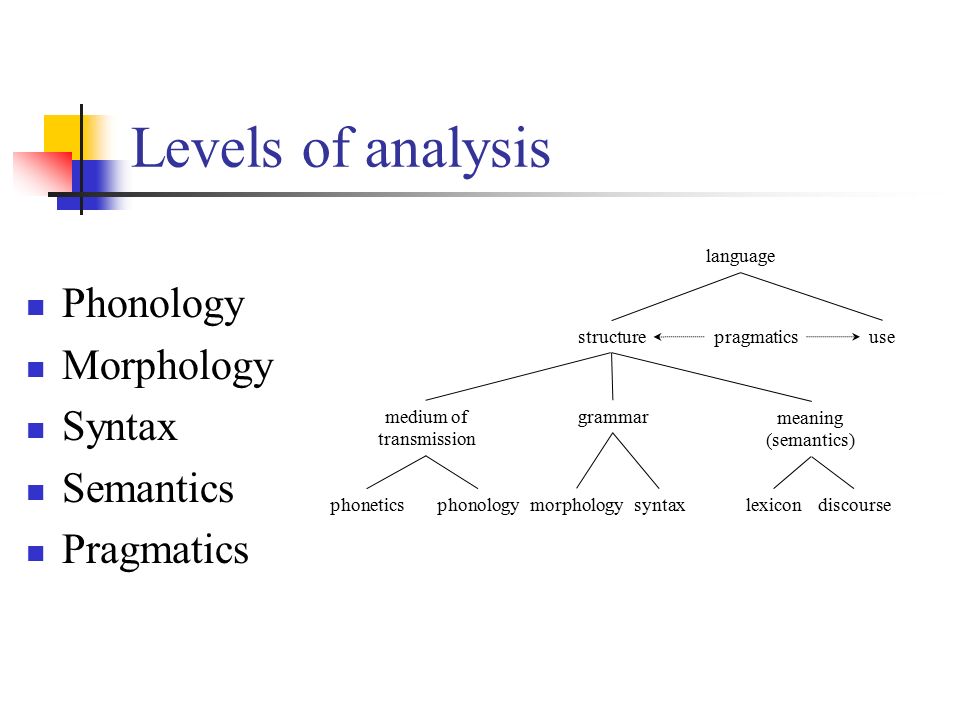

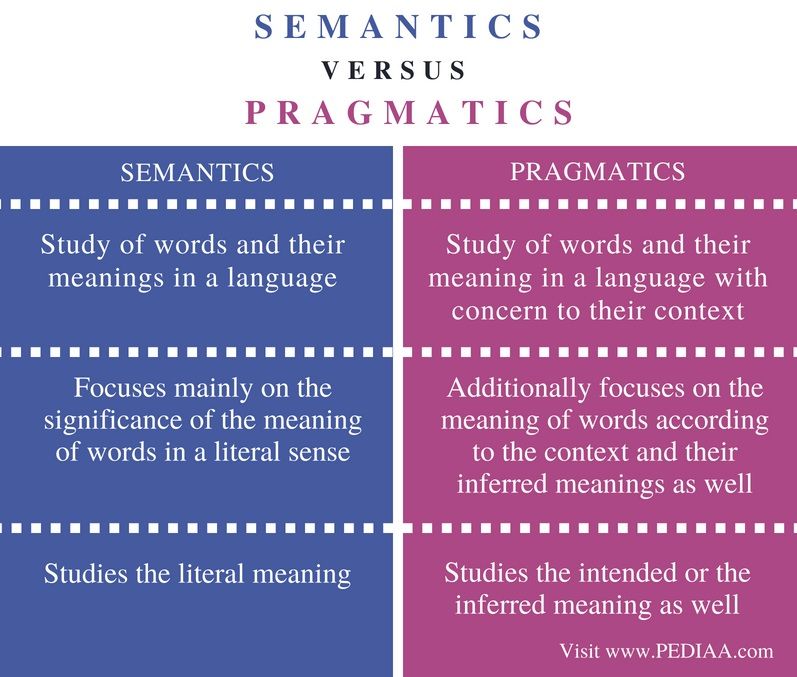

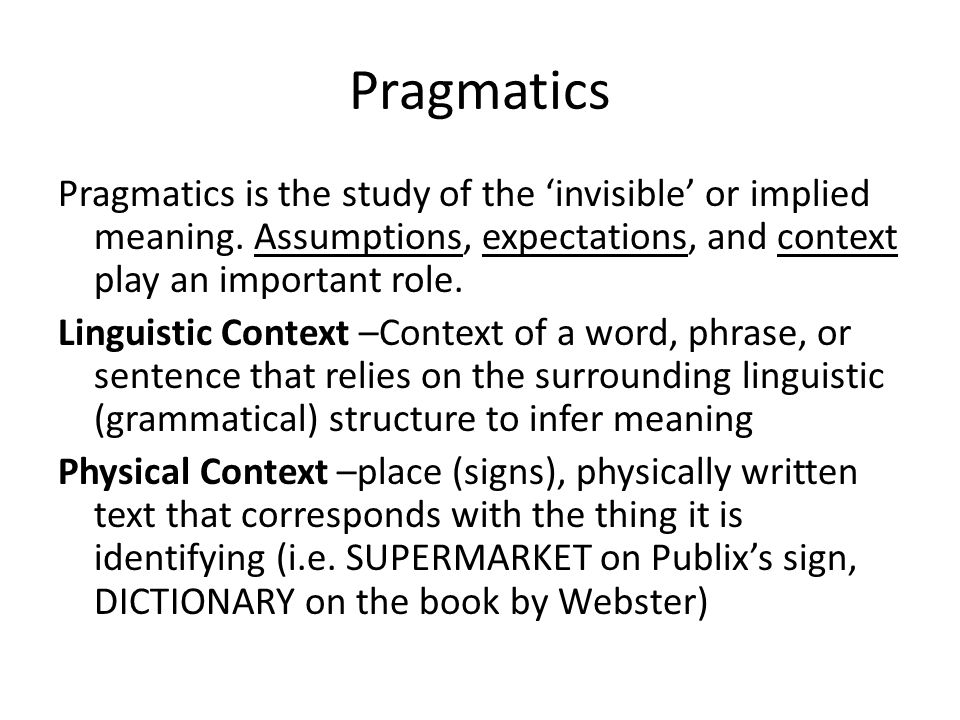

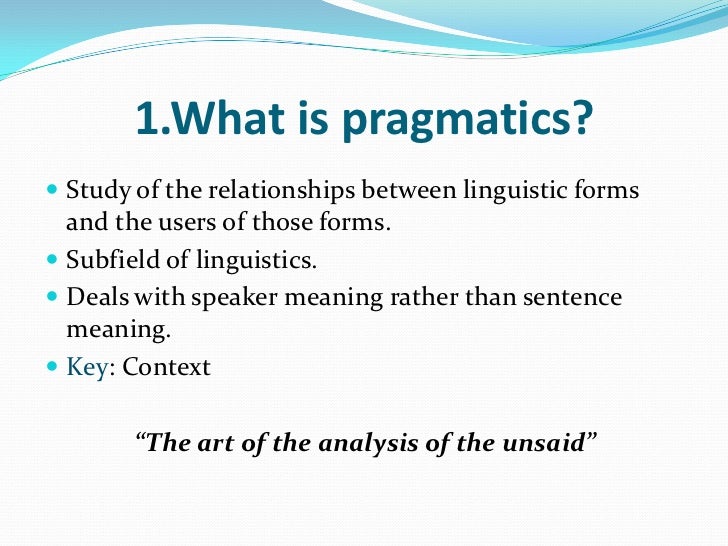

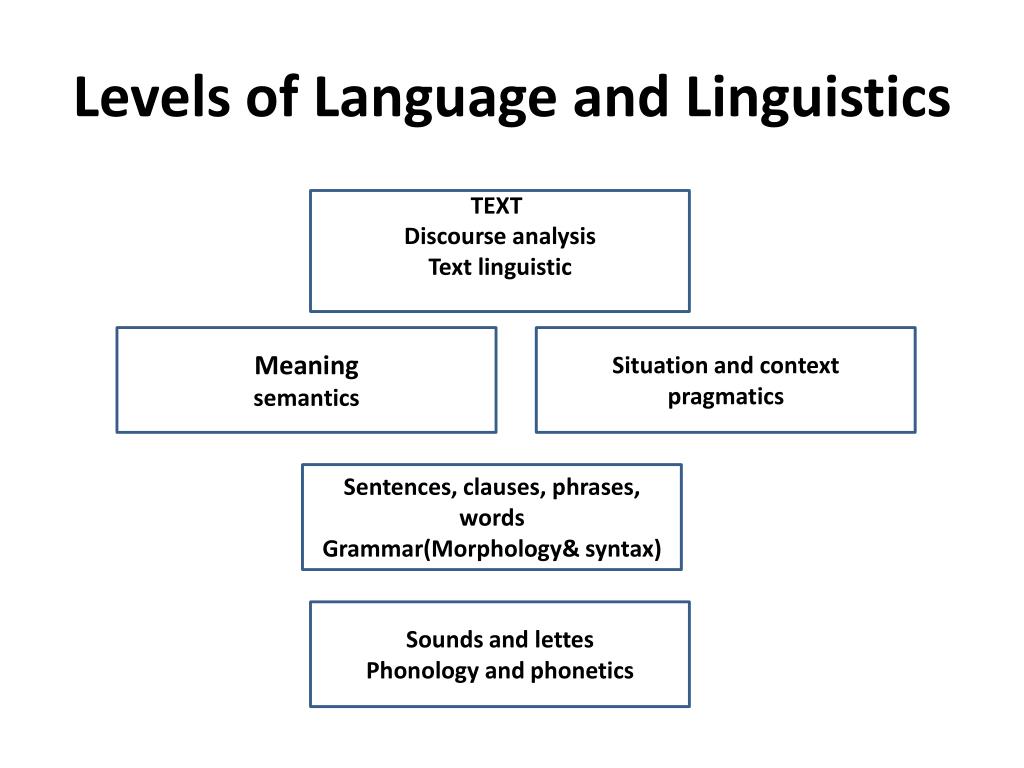

□ Pragmatics is a branch of semiotics. He studies the features of the use of signs in communication, the relationship of signs to the interpreter.

Pragmatic factors include a wide variety of information. This information makes it possible to establish the meaning of linguistic expressions and statements in a directly given situational (pragmatic) context.

■ NV Voloshinov gives the following example. Two people are sitting in a room. They are silent. One says: Yes! Taken in isolation, it has a meaning, but it has no meaning, since it can be related to any situation and take on any meaning in this situation. The meaning of the statement is clarified only if the situation of communication in which this expression is pronounced is clarified. Suppose, continues N. V. Voloshinov, at the moment of the conversation, the interlocutors, looking out the window, see snow; moreover, they know that it is already May and that it is high time to be spring; the prolonged winter is tired, and they are upset by the late snowfall. As a meaningful whole, the statement thus consists of two parts: the verbally realized (actualized) part and the implied part.

The meaning of the statement is clarified only if the situation of communication in which this expression is pronounced is clarified. Suppose, continues N. V. Voloshinov, at the moment of the conversation, the interlocutors, looking out the window, see snow; moreover, they know that it is already May and that it is high time to be spring; the prolonged winter is tired, and they are upset by the late snowfall. As a meaningful whole, the statement thus consists of two parts: the verbally realized (actualized) part and the implied part.

This kind of "knowledge in brackets" is included in the interpretation as an implicit component of the utterance. But it can hardly be justified semantically, since there are no such semantic rules by which it could be associated with the explicit content of the statement.

■ Let's take the saying It's cold! Out of context, this linguistic expression can mean anything: in the appeal of a coquette to the boyfriend - “hug me”, in the appeal of the wife to her husband - “it is necessary to seal the windows”, in the appeal of the boss to the subordinate - “close the window”, “bring hot tea” and etc. As a variable, the meaning of the statement thus depends on the conditions of use, or rather, on the pragmatic context and the typical scenario associated with it, which models the behavior of the persons involved in accordance with the distribution of roles that has developed in society - in our case, suitors, husbands and subordinates.

As a variable, the meaning of the statement thus depends on the conditions of use, or rather, on the pragmatic context and the typical scenario associated with it, which models the behavior of the persons involved in accordance with the distribution of roles that has developed in society - in our case, suitors, husbands and subordinates.

■ As another example, consider this conversation on public transport:

- What time is it? (he)

- I am happy (she)

Correct understanding of the words included in the statement does not exclude incorrect interpretation. It is possible to understand why a random fellow traveler answers a request for information about the time of day by admitting that she is in the best mood only against the background of the well-known “catch-phrase” Happy hours are not observed. In the absence of such a background, the statement I am happy is perceived as abnormal, as not meeting the requirements of "cooperative" communication, which, according to G. P. Grice, is required from the participants in communication.

P. Grice, is required from the participants in communication.

■ Another example. The statement It will rain can be understood differently depending on what meaning the speaker puts into it: (i) whether he is looking forward to rain during a drought, (ii) he is going to take a plane, (iii) he is considering whether to take an umbrella, ( iv) nothing to say or (v) simply bored.

As an external variable, the pragmatic component thus refers not to the sentence, but to the statement, through which the speaker expresses his attitude to the fact of the statement. Without this, the meaning of the phrase seems incomplete, and the questions of where, when it will rain and what do I care about this do not find an answer.

□ Any background knowledge functions as pragmatic factors of meaning in interpretation.

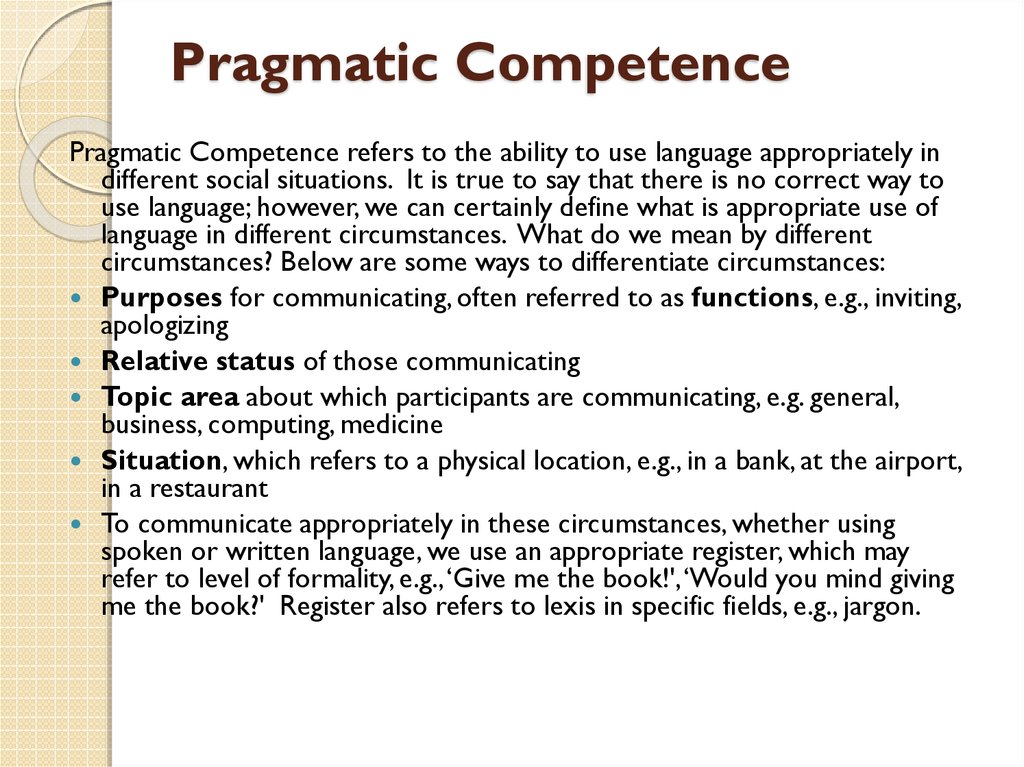

□ Pragmatic factors include a wide variety of information, and this information is given depending on research priorities as encyclopedic knowledge, social norms, frames, propositional attitudes, intentions, opinions and beliefs. This information makes it possible to establish the meaning of the analyzed statements in a directly given situational context.

This information makes it possible to establish the meaning of the analyzed statements in a directly given situational context.

Social norms. The pragmatic factors include the so-called social (cultural) norms, various kinds of social institutions, one way or another affecting the nature of the comprehension of the statement - "the opinion of the majority" in Plato's definition, "what seems right to all or most people" in Aristotle's definition, " prejudices” (préjugés) in the definition of H.-G. Gadamer, "implied" family, clan, nation, class, social group in the definition of V. N. Voloshinov.

Indeed, along with the functional system of language, other “system instances” (F. Rastier) have to be taken into account in the interpretation of linguistic works. And not only because any communicative situation is modeled in accordance with some type of scenario, but also because the specific lexical and grammatical support that the language has to designate relations within the situation is brought into line with the generally valid convention of how to behave how to understand and what to say in a similar situation. For example, when an outraged buyer says to a salesperson, "You've given me weight!", sellers are supposed not to give buyers weight. In this understanding, the implied part of the statement is consistent with the system of opinions and ideas that has developed in society. Social norms thus act as a function of a pragmatic presupposition.

For example, when an outraged buyer says to a salesperson, "You've given me weight!", sellers are supposed not to give buyers weight. In this understanding, the implied part of the statement is consistent with the system of opinions and ideas that has developed in society. Social norms thus act as a function of a pragmatic presupposition.

□ Social norms are complementary coding systems.

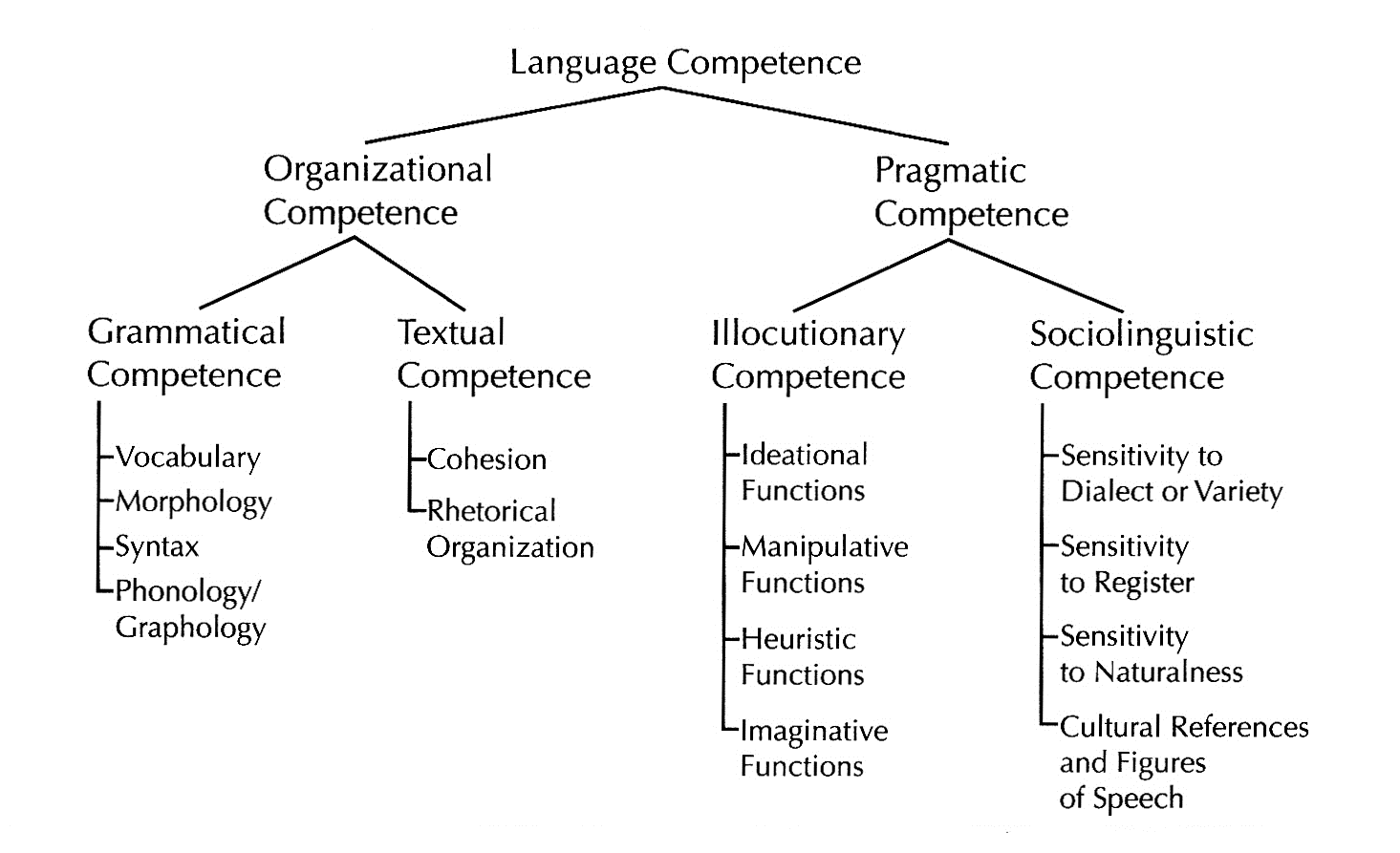

□ Knowledge of a language system corresponds to semantic competence, knowledge of social norms incorporated in a work corresponds to pragmatic competence.

□ Social norms “correct” the systemic meaning fixed in the language within a given subject (conceptual) area.

□ Normative judgments cannot be given a truth value, but can only be checked for compliance with some norm within the limits of “permissible” ‒ “unacceptable”, “appropriate” ‒ “inappropriate”, “possible” ‒ “impossible”.

► Q&A

• When you are offered coffee and you say I have to get up early tomorrow, what is a pragmatic presupposition?

• Give examples when the pragmatic competence allows to “correct” in the context the systemic meaning of the words and expressions included in the statement.

• Give examples when, in the absence of a pragmatic context, the most banal phrase becomes ambiguous or ambiguous.

► Comment

• Pragmatic factors include a wide variety of information.

• The interpretation of statements cannot be limited to the functional system of the language.

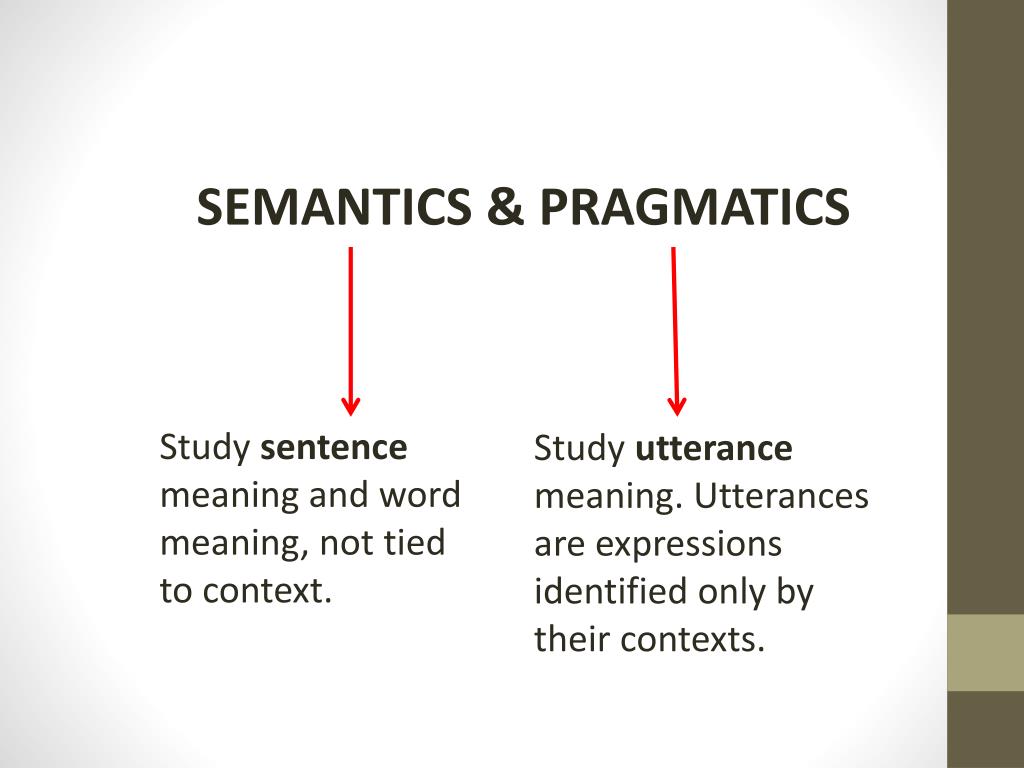

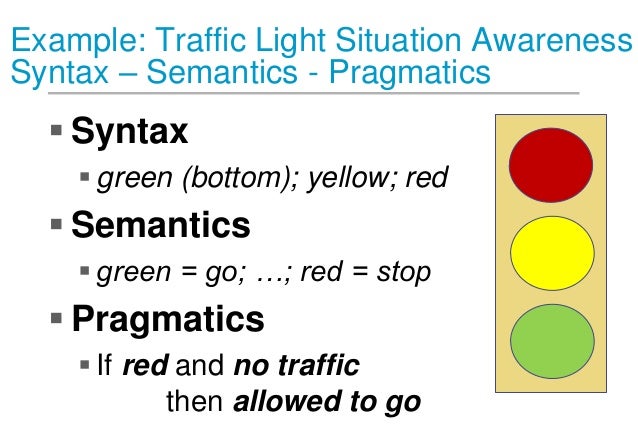

• Semantics is given conventional meanings established in the language system, pragmatics - their direct use in speech.

• Comprehension is provided by knowledge of the meaning of words and sentences (semantic competence), interpretation by knowledge of the mechanisms of language use (pragmatic competence). The object of understanding is a constant value; the interpretation is aimed at the variable communicative meaning of the words in the statement and the statements themselves (N. D. Arutyunova).

• In a variable pragmatic situation, the meaning of all words and phrases included in the utterance can only be variable.

• Along with the linguistic context, a broad pragmatic context can also function as an interpreter.

• To understand the meaning of the analyzed language sequence, one language encoding/decoding is not enough.

• Pragmatic presuppositions function like an enthymeme, or an abbreviated syllogism, when you can omit (not say) what is known.

Recommended reading

Arutyunova ND Pragmatics // Linguistic Encyclopedic Dictionary. M.: Soviet Encyclopedia, 1990. S. 389‒390.

Bochkarev A. E. Semantics. Basic lexicon. Nizhny Novgorod: DECOM, 2014.

Van Dijk T. A. Questions of text pragmatics // New in foreign linguistics. Issue. VIII. Linguistics of the text. M.: Progress, 1978. S. 259‒336.

Appendix I. Pragmatic context in a literary text

■ Background knowledge pushes the boundaries of the text up to the inclusion of versatile information here - information about the author, genre, historical era, conditions for creating a work, its modern reception ... Of course, not the entire fund of knowledge accumulated by philology, historiography becomes in demand or literary criticism, but only such knowledge, without which it is impossible to do in understanding. For example, the modern reader does not understand why in the novel by A. S. Pushkin "Eugene Onegin" Lensky's neighbor in the village is compared with a Roman poet and how the phrase "plant cabbage" in the expression Plants cabbage like Horace should be understood (ch. 6, VII). V. V. Nabokov explains: “In fact, this is a common Gallicism planter des (ses) choux, meaning “to live in the village”.”

For example, the modern reader does not understand why in the novel by A. S. Pushkin "Eugene Onegin" Lensky's neighbor in the village is compared with a Roman poet and how the phrase "plant cabbage" in the expression Plants cabbage like Horace should be understood (ch. 6, VII). V. V. Nabokov explains: “In fact, this is a common Gallicism planter des (ses) choux, meaning “to live in the village”.”

■ In a similar way, in order to understand why Zaretsky is characterized as the father of a family unmarried (Ch. 6, VII) and how to neutralize the contradiction in general, it is useful to know how such a characterization was perceived by Pushkin's contemporaries. From the point of view of formal logic, this is a contradictory definition: by definition, the father of a family cannot be single, and a single man cannot be the father of a family. To remove the contradiction, it is necessary to neutralize one of the counter signs: /single/ or /married/. In this case, one of the definitions will be taken literally, the other - in a figurative sense: for example. ‘single’ (formally) ‒ ‘father of the family’ (actually). But in order to be sure of the correctness of the paraphrase, one cannot do without reconstructing the cultural-historical situation – what is sometimes called the “correct historical horizon” (Gadamer) – is indispensable. Yu. M. Lotman explains: “Despite its ironic nature, this expression was almost a term for the owner of a serf harem and could be used in a neutral context.” And Pushkin's contemporaries did not see, therefore, contradictions; and there were no difficulties in understanding: as soon as the landowner owns the serfs, he has the right to dispose of them, while remaining an “honest and good person”, at his own discretion - up to the creation of a harem of serf girls. Such representations are interpretants in the function of pragmatic presupposition.

‘single’ (formally) ‒ ‘father of the family’ (actually). But in order to be sure of the correctness of the paraphrase, one cannot do without reconstructing the cultural-historical situation – what is sometimes called the “correct historical horizon” (Gadamer) – is indispensable. Yu. M. Lotman explains: “Despite its ironic nature, this expression was almost a term for the owner of a serf harem and could be used in a neutral context.” And Pushkin's contemporaries did not see, therefore, contradictions; and there were no difficulties in understanding: as soon as the landowner owns the serfs, he has the right to dispose of them, while remaining an “honest and good person”, at his own discretion - up to the creation of a harem of serf girls. Such representations are interpretants in the function of pragmatic presupposition.

■ The entire cultural-historical situation in which the production and interpretation of the text takes place acts as a pragmatic context. For example, the modern reader is unaware of what the pink wafer, which dries on the inflamed tongue of Tatyana Larina, means in A. S. Pushkin's novel "Eugene Onegin". Turning to the "Dictionary of the Russian Language", you can read that a cachet is "a small ball of starch flour, gelatin, etc., hollow inside, for taking medicines in powders. Quinine in wafers” (S.I. Ozhegov). Really, the question arises, did Tatyana suffer from malaria? Looking at the encyclopedic dictionary, you can also find out that the wafer is related to the rite of communion in the Catholic Church. Does this mean, asks a well-known domestic researcher, that Tatyana was a secret Catholic? Meanwhile, V. Nabokov explains: “Envelopes have not yet been invented; the folded letter was sealed with a special adhesive paste with a pink tint in the form of a circle, as in this case. The reconstruction of the cultural-historical situation thus makes it possible to recreate the “correct historical horizon” (H.-G. Gadamer), without taking into account which even the most ordinary expression like a pink cloud may seem anomalous.

S. Pushkin's novel "Eugene Onegin". Turning to the "Dictionary of the Russian Language", you can read that a cachet is "a small ball of starch flour, gelatin, etc., hollow inside, for taking medicines in powders. Quinine in wafers” (S.I. Ozhegov). Really, the question arises, did Tatyana suffer from malaria? Looking at the encyclopedic dictionary, you can also find out that the wafer is related to the rite of communion in the Catholic Church. Does this mean, asks a well-known domestic researcher, that Tatyana was a secret Catholic? Meanwhile, V. Nabokov explains: “Envelopes have not yet been invented; the folded letter was sealed with a special adhesive paste with a pink tint in the form of a circle, as in this case. The reconstruction of the cultural-historical situation thus makes it possible to recreate the “correct historical horizon” (H.-G. Gadamer), without taking into account which even the most ordinary expression like a pink cloud may seem anomalous.

Lexical pragmatics of the Russian language - Interdepartmental Dictionary Room named after prof.

B.A. Larina

B.A. Larina " Vocabulary of the Russian language with a pragmatic component of semantics " is a scientific project of lexicographers - employees of the Interdepartmental Dictionary Office of St. Petersburg State University, dedicated to the study of the pragmatic aspects of the most commonly used modern all-Russian vocabulary.

The project was supported by the Russian Humanitarian Science Foundation and is being implemented with its financial support (RHF grant, No. 15-04-00373).

Head: E. B. Kuzmina .

Project participants: O. V. Vasilyeva, I. S. Kukushkina, E. V. Puritskaya .

The subject of scientific research is the pragmatics of a single word (lexical pragmatics), that is, the influence of the pragmatic component of a linguistic sign on its functioning, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the modification of the semantics of a word in speech, depending on the goals of the statement, the speech situation , the status of interlocutors, the subject of speech, aesthetic, emotive components of speech, etc. "Russian vocabulary with a pragmatic component of semantics" is an experimental scientific topic, the novelty of which is determined by the fact that the dictionary compiled as a result of this study will be the first dictionary in lexicographic practice where the pragmatic component of a word is purposefully singled out as a special subject of lexicographic analysis and description.

"Russian vocabulary with a pragmatic component of semantics" is an experimental scientific topic, the novelty of which is determined by the fact that the dictionary compiled as a result of this study will be the first dictionary in lexicographic practice where the pragmatic component of a word is purposefully singled out as a special subject of lexicographic analysis and description.

The relevance of the work is determined, on the one hand, by the general tendency of linguistics to study a really functioning language (to the problems of linguistic pragmatics in general), on the other hand, by the lack of development of lexicographic pragmatics as a science.

The results of the study will be presented in the form of dictionary of lexical pragmatics of the Russian language (volume 20 a.l.), which has a communicative orientation and great practical importance for all students of the Russian language in its real functioning.

MSK im. prof. B. A. Larina holds regular meetings to discuss the scientific problems of lexical pragmatics, compiling and reviewing dictionary entries.