Colleen thompson eating disorders

Talking About Eating Disorders - Uptown Dallas Counseling

/in eating disorder /by Holly ScottThe holiday season is filled with parties and social events where food in a central focus. As we gather together with others, the subjects of how much, what, when, and why we eat are common topics. Often, a well-meaning friend or relative will use these conversations about food to bring up concerns about someone with an eating disorder. They believe talking about eating disorders with a relative might be helpful. If you are thinking about reaching out to someone you think may be struggling, it is best to educate yourself on the facts of these disorders before starting a discussion.

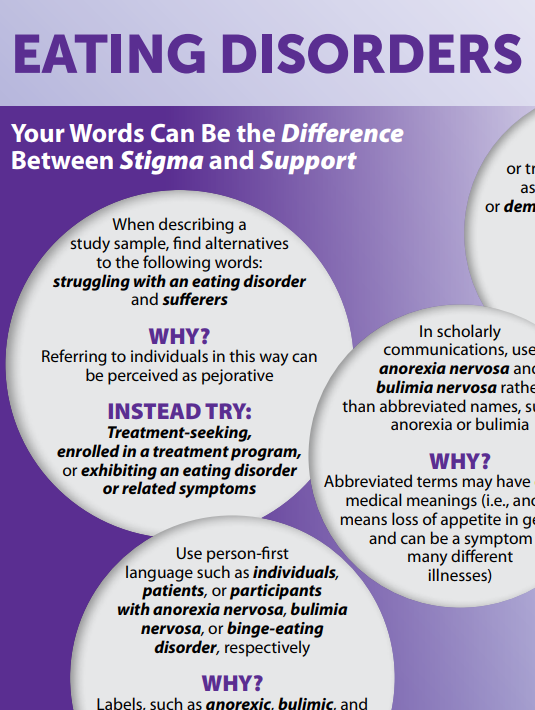

Colleen Thompson has helpful suggestions about things to say or do when you first approach someone. She lists them in her article on www.HealthyPlace.com.

- Avoid talking about food and weight, those are not the real issues

- Assure them that they are not alone and that you love them and want to help in any way that you can

- Encourage them to seek help

- Never try to force them to eat

- Do not comment on their weight or appearance

- Do not blame the individual and do not get angry with them

- Be patient, recovery takes time

- Do not make mealtimes a battleground

- Listen to them, do not be quick to give opinions and advice

- Do not take on the role of a therapist

Remember: Constant Supportive Compassion

Holly Scott, MBA, MS, LPC sees clients at Uptown Dallas Counseling. Holly is trained in the specialty of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and holds the position of Diplomate in the Academy of Cognitive Therapy. Holly works with clients to help them overcome challenges in their daily lives that may be preventing them from achieving happiness. She helps clients with stress management, depression, parenting, marriage counseling, and other mental health concerns. If you are looking for a counselor or therapist in t!he Uptown Dallas area, explore this website to see if Holly may be able to help you.

To make an appointment for therapy or counseling with Holly at her Uptown Dallas Counseling, you have the option of using the Online Patient Portal to register and schedule. If you would prefer to talk with Holly to schedule an appointment, email [email protected], or call 214-953-9366, to talk with her about your counseling needs.

Tags: do I have an eating disorder, treating eating disorders, what is an eating disorderShare this entry

com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Holly-Scott-Logo-150.png 0 0 Holly Scott https://uptowndallascounseling.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Holly-Scott-Logo-150.png Holly Scott2013-12-06 00:54:002014-02-08 00:36:29Talking About Eating Disorders

com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Holly-Scott-Logo-150.png 0 0 Holly Scott https://uptowndallascounseling.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Holly-Scott-Logo-150.png Holly Scott2013-12-06 00:54:002014-02-08 00:36:29Talking About Eating Disorders About Us - Mirror-Mirror

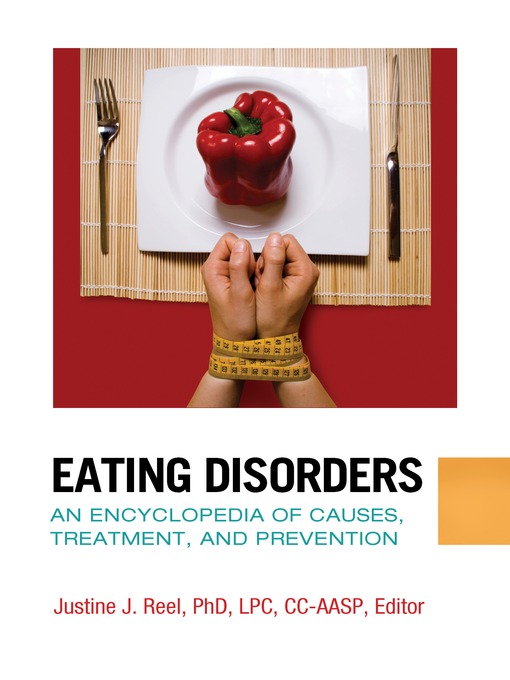

This website was originally created in 1997 by Colleen Thompson, while she was recovering from an eating disorder. She hoped to provide education and support for others with eating disorders while also educating herself and working through some of the issues that she struggled with personally.

Dr. Stacey Rosenfeld, Editor

Dr. Stacey Rosenfeld is a licensed psychologist, certified group psychotherapist, certified eating disorder specialist, and the author of Does Every Woman Have an Eating Disorder? Challenging Our Nation’s Fixation with Food and Weight. She has worked at treatment centers and universities around the U. S., including Columbia University Medical Center in New York and UCLA in Los Angeles. Dr. Rosenfeld is the director of Gatewell Therapy Center in Miami and works with individuals, couples, families, and groups, using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical-behavioral therapy (DBT), psychodynamic therapy, and motivational interviewing approaches. Dr. Rosenfeld is a member of the Academy for Eating Disorders, the International Association for Eating Disorder Professionals, the Binge Eating Disorder Association, and the Eating Disorders Coalition of Miami.

S., including Columbia University Medical Center in New York and UCLA in Los Angeles. Dr. Rosenfeld is the director of Gatewell Therapy Center in Miami and works with individuals, couples, families, and groups, using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical-behavioral therapy (DBT), psychodynamic therapy, and motivational interviewing approaches. Dr. Rosenfeld is a member of the Academy for Eating Disorders, the International Association for Eating Disorder Professionals, the Binge Eating Disorder Association, and the Eating Disorders Coalition of Miami.

Dr. Elisha Carcieri, Editor and Writer

Elisha Carcieri, Ph.D., is a licensed clinical psychologist (PSY #26716). Dr. Carcieri earned her bachelors degree in psychology from The University of New Mexico and completed her doctoral degree in clinical psychology at Saint Louis University. During her graduate training, she conducted research focused on eating disorders and obesity, and was trained in using cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for eating disorders and other mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression. Dr. Carcieri completed her postdoctoral fellowship at the Long Beach VA Medical Center, where she worked with Veterans coping with mental illness, disability, significant acute or chronic health concerns, and chronic pain. In addition to cognitive behavioral strategies, she is also a proponent of alternative evidence-based approaches such as mindfulness, and acceptance and commitment-based strategies, depending on the needs of each client. Dr. Carcieri has experience working with culturally diverse clients representing various aspects of diversity including race/ethnicity, gender, age, disability, and size. She is currently living in Charleston and working as a full-time mom to her two sons, ages 3 and 1. Dr. Carcieri is a member of the Academy for Eating Disorders (AED). She can be reached via email at [email protected].

Dr. Carcieri completed her postdoctoral fellowship at the Long Beach VA Medical Center, where she worked with Veterans coping with mental illness, disability, significant acute or chronic health concerns, and chronic pain. In addition to cognitive behavioral strategies, she is also a proponent of alternative evidence-based approaches such as mindfulness, and acceptance and commitment-based strategies, depending on the needs of each client. Dr. Carcieri has experience working with culturally diverse clients representing various aspects of diversity including race/ethnicity, gender, age, disability, and size. She is currently living in Charleston and working as a full-time mom to her two sons, ages 3 and 1. Dr. Carcieri is a member of the Academy for Eating Disorders (AED). She can be reached via email at [email protected].

Eva Musby, Community Liaison, Advocate and Writer

Eva Musby is a respected author, and has created resources to help parents in support of their children with an eating disorder. Her work is the result of personal experience (her child suffered from anorexia age 10), and is supported by research, writings, and accounts from parents and professionals across the world. Her book ‘Anorexia and other eating disorders – How to help your child eat well and be well’, and her videos, are recommended by eating disorder experts and parents world-wide. She also offers individual support to parents. You can contact Eva at her Website or on Twitter.

Her work is the result of personal experience (her child suffered from anorexia age 10), and is supported by research, writings, and accounts from parents and professionals across the world. Her book ‘Anorexia and other eating disorders – How to help your child eat well and be well’, and her videos, are recommended by eating disorder experts and parents world-wide. She also offers individual support to parents. You can contact Eva at her Website or on Twitter.

Molly Bahr, Editor and Writer

Molly Bahr is a Licensed Mental Health Counselor with a private practice in Miami, Florida. She is a Certified Intuitive Eating Counselor, trained in EMDR, and practices from a Health At Every Size lens. Molly earned her masters of counseling degree from the University of Colorado Denver and undergrad degree in psychology at Arizona State University. The focus of her practice is on helping people make peace with food and their body while creating a full and meaningful life. Molly works with disordered eating, body shame, anxiety, depression, and trauma. Molly has worked in a variety of treatment settings including inpatient and outpatient programs for eating disorders, substance abuse disorders, and an outpatient transgender clinic. She is also a member of the International Association for Eating Disorder Professionals. You can find her on Instagram, where she promotes body acceptance, body liberation, information to improve mental health and your relationship with food and body, or her website.

Molly works with disordered eating, body shame, anxiety, depression, and trauma. Molly has worked in a variety of treatment settings including inpatient and outpatient programs for eating disorders, substance abuse disorders, and an outpatient transgender clinic. She is also a member of the International Association for Eating Disorder Professionals. You can find her on Instagram, where she promotes body acceptance, body liberation, information to improve mental health and your relationship with food and body, or her website.

Lauren Koffler, Dietitian Nutritionist

Lauren Koffler is a registered dietitian nutritionist based in New York City with a master’s degree in clinical nutrition from NYU. Lauren has experience in both clinical and academic settings, and she has worked with a variety of patient/client populations. Throughout these experiences, Lauren’s counseling has continuously focused on long-term, sustainable health promotion and disease prevention with an emphasis on intuitive eating, body positivity, and the ability to achieve health at every size. Lauren is a member of the New York chapter of the International Association of Eating Disorders Professionals as well as the Binge Eating Disorder Association.

Lauren is a member of the New York chapter of the International Association of Eating Disorders Professionals as well as the Binge Eating Disorder Association.

Tabitha Farrar, Writer

Tabitha Farrar is an eating disorder recovery coach and founder of the new innovative online meal support service for people in recovery from eating disorders such as Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating disorder (if you or someone you know would benefit from meal support in eating disorder recovery then please visit her website).

Our Mission

Today, our mission is to build upon Colleen Thompson’s work by providing information, education, and support to the community, including people dealing with eating disorders themselves and loved ones that want to support friends or family members with eating disorders.

We want to help you get the help you need to recover. We want to support you as you’re supporting a loved one with an eating disorder. We want you to succeed and to have a happy, healthy life.

We want you to succeed and to have a happy, healthy life.

We also want to help parents, educators, and other adults that work with children and adolescents to be more aware of the signs and symptoms of eating disorders, so they can provide early intervention when needed. We want parents and educators to know what they can do to help prevent eating disorders in young people, but we also want them to know that eating disorders can occur no matter what you do, and if it happens to a child you care about, we want to support you in helping that child.

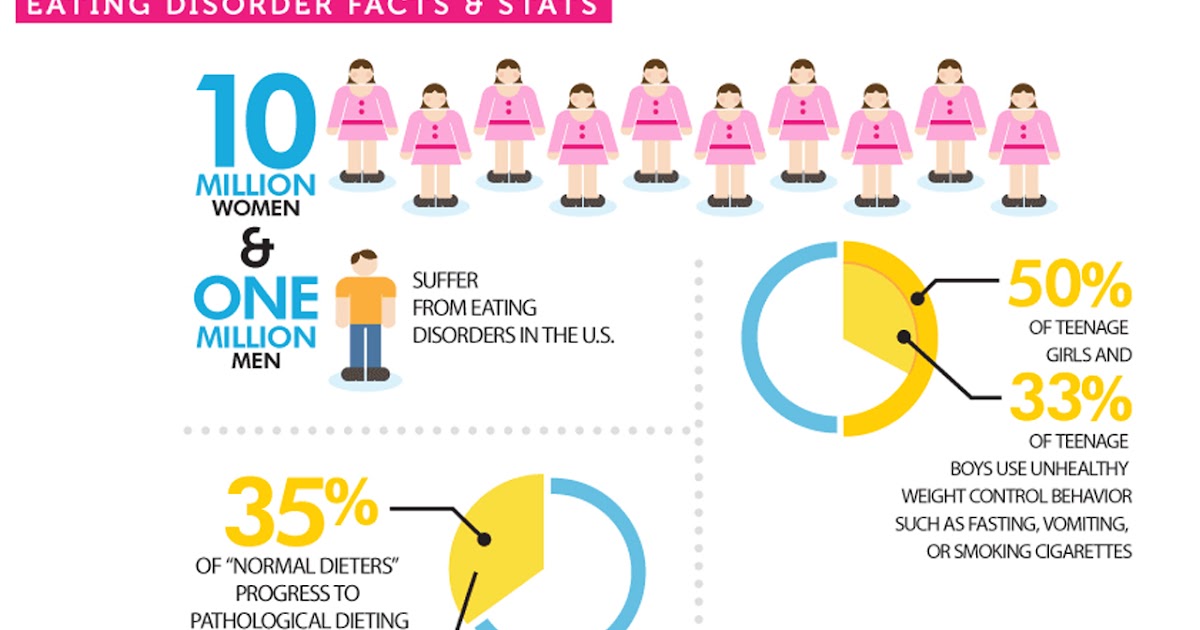

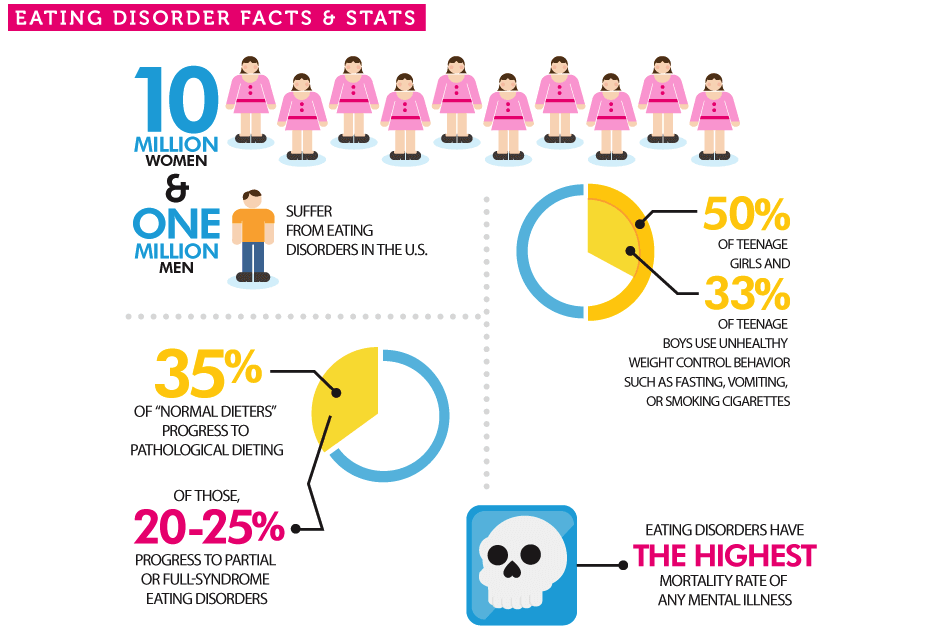

We want you to know you’re not alone. According to the National Eating Disorder Association, an estimated eleven million Americans struggle with eating disorders. Eating disorders affect people of all ages, men and women, people from all walks of life.

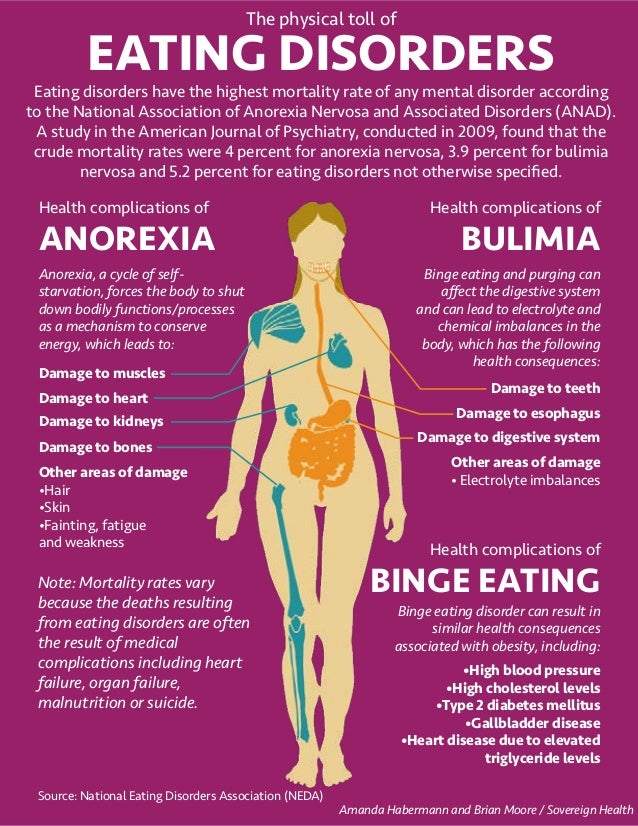

Unfortunately, some people with eating disorders will not survive. Anorexia is considered to be the most lethal of all psychological disorders. But we want you to be one of the survivors. We want you to know help is available and recovery is possible. We want to assist you on your journey to good health.

We want you to know help is available and recovery is possible. We want to assist you on your journey to good health.

If You Need More Information

If you aren’t finding the information you need here, please email us. We’ll try to get you the information you need or direct you to other sources of information. We can’t give you medical advice, but we’ll do all we can to assist you.

If You Think You or a Loved One Needs Help with an Eating Disorder

This website is not a substitute for professional treatment and advice. If it’s not an emergency, you can call your primary care physician or your counselor, if you are currently in counseling. If you aren’t currently in counseling but want to talk to a counselor or are interested in a treatment program, you’ll find a list of treatment centers on this website, or you can ask your primary care physician for a referral, or you can check with your health insurance company to find out which counselors and eating disorder treatment programs are covered on your plan.

If You Need Immediate Assistance

If you, or someone you love, needs immediate assistance, please call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room. Help is available and we want you to get the help you need.

If You Want To Get Involved

If you want to help and are not sure where to start, become an eating disorder advocate. Your efforts may help others, and you may find it empowering to be involved.

Return To Home Page

Premenstrual syndrome and eating disorders » Obstetrics and Gynecology

Most women, regardless of cultural and socio-economic level, experience psychosomatic and behavioral changes before menstruation. This phenomenon is called premenstrual syndrome (PMS), when the degree of discomfort is so great that it interferes with daily activities, relationships with the environment and the woman's quality of life. A severe form of PMS is premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Among the premenstrual symptoms, eating disorders are described, partly causing weight fluctuations on the eve of menstruation and sometimes acquiring the character of a mental disorder. Eating disorders depend on fluctuations in the hormonal profile and changes in the ratios of steroid hormones. This creates the possibility of using combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives to treat eating disorders dependent on hormonal imbalance. As you know, the effects of hormonal contraceptives are determined by the pharmacological properties of the progestins that make up their composition. IV generation progestin - drospirenone has a unique spectrum of antimineralocorticoid and antiandrogenic activity, which gives preparations containing drospirenone special therapeutic and prophylactic effects, which are also significant in cases of eating disorders. nine0003

Among the premenstrual symptoms, eating disorders are described, partly causing weight fluctuations on the eve of menstruation and sometimes acquiring the character of a mental disorder. Eating disorders depend on fluctuations in the hormonal profile and changes in the ratios of steroid hormones. This creates the possibility of using combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives to treat eating disorders dependent on hormonal imbalance. As you know, the effects of hormonal contraceptives are determined by the pharmacological properties of the progestins that make up their composition. IV generation progestin - drospirenone has a unique spectrum of antimineralocorticoid and antiandrogenic activity, which gives preparations containing drospirenone special therapeutic and prophylactic effects, which are also significant in cases of eating disorders. nine0003

Despite the general interest in obesity and underweight, eating disorders attract the attention mainly of psychiatrists and neurologists. At the same time, the normalization of body weight is considered the most important task in the treatment of many diseases, including gynecological ones, and it is impossible to imagine an effective weight correction in case of impaired eating behavior [1]. In some cases, eating disorders are an integral part of the disease, examples of which are premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). nine0003

At the same time, the normalization of body weight is considered the most important task in the treatment of many diseases, including gynecological ones, and it is impossible to imagine an effective weight correction in case of impaired eating behavior [1]. In some cases, eating disorders are an integral part of the disease, examples of which are premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). nine0003

The term "premenstrual tension" was first proposed by Frank in 1931, and "premenstrual syndrome" by Greene and Dalton in 1953, but it is still a mystery why more than 20% of women in the fertile population 2] are so " sensitive" to their menstrual cycle, that they suffer from the onset of its second phase.

According to M.N. Kuznetsova (1972), "premenstrual syndrome is a complex pathological symptom complex of neuropsychic, vegetative-vascular and metabolic-endocrine disorders, which combines at least 3-4 pronounced symptoms that appear 2-10 days before menstruation and disappear during the first days of menstruation" . Among the approximately 200 physical and mental symptoms of PMS, weight fluctuations and eating disorders are described. Changes in appetite and food perversion are more often referred to as PMDD as a more severe condition of the premenstrual period [3]. nine0003

Among the approximately 200 physical and mental symptoms of PMS, weight fluctuations and eating disorders are described. Changes in appetite and food perversion are more often referred to as PMDD as a more severe condition of the premenstrual period [3]. nine0003

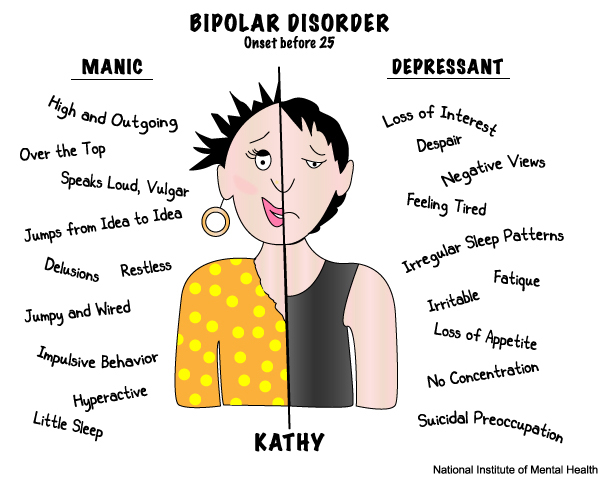

Late luteal dysphoric disorder was identified and added to the DSM-III-R section entitled "Suggested diagnostic categories for further study" in 1987. Seven years later, the "late luteal dysphoric disorder" working group recommended that the condition be included in the DSM-IV section "Mood disorders not otherwise specified" under the heading "premenstrual dysphoric disorder". PMDD is currently defined as a severe form of PMS that includes physical, psychological and behavioral symptoms that recur regularly during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and decrease within a few days of the onset of menstruation [4]. The criteria for this condition, which occurs in 3-8% of women in the population, are the following positions. nine0003

nine0003

A. For most menstrual cycles in the last year, five or more of the following symptoms (at least one of symptoms 1, 2, 3, 4 must be present) were observed for the longest time during the last week of the luteal phase, began to subside within a few days after the onset of the follicular phase and were absent within a week after the cessation of menstruation:

- clearly depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness or ideas of self-abasement; nine0015 appreciable anxiety, tension, a feeling of agitation;

- severe emotional lability;

- anger or irritability, or aggravation of interpersonal conflicts;

- subjective feeling of difficulty concentrating;

- drowsiness, fatigue or marked lack of energy;

- marked change in appetite, overeating or craving for particular foods;

- pathological drowsiness or insomnia; nine0015 subjective feeling of shock or loss of control;

- somatic symptoms, eg painful breast engorgement, headaches, joint or muscle pain, bloating, weight gain.

B. The disorder noticeably interferes with work or study or regular social activities and relationships with others.

B. Possible exacerbation of symptoms of another medical condition, such as depression, panic disorder, dysthymic disorder, or personality disorder. nine0003

D. Criteria A, B, and C must be confirmed by prospective daily assessments for at least two consecutive symptomatic cycles (preliminary diagnosis may be made prior to this confirmation).

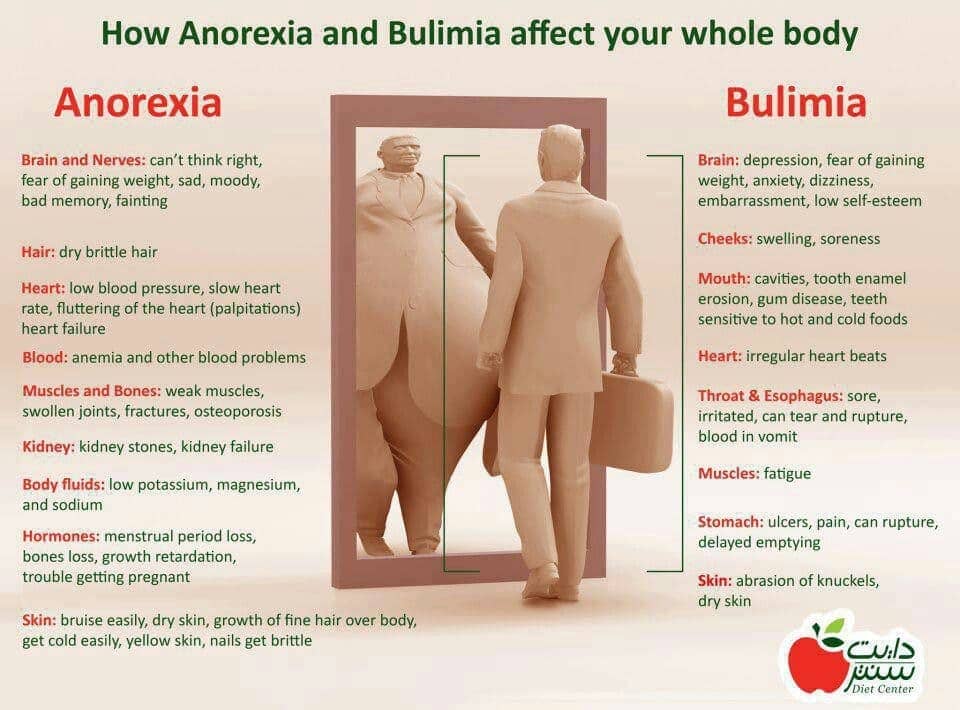

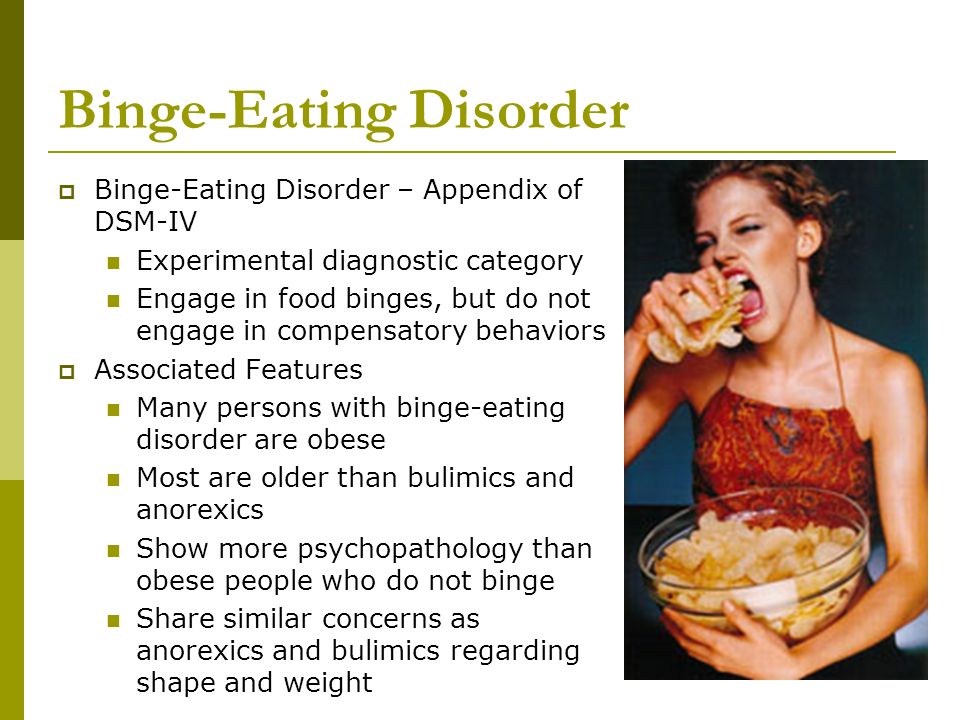

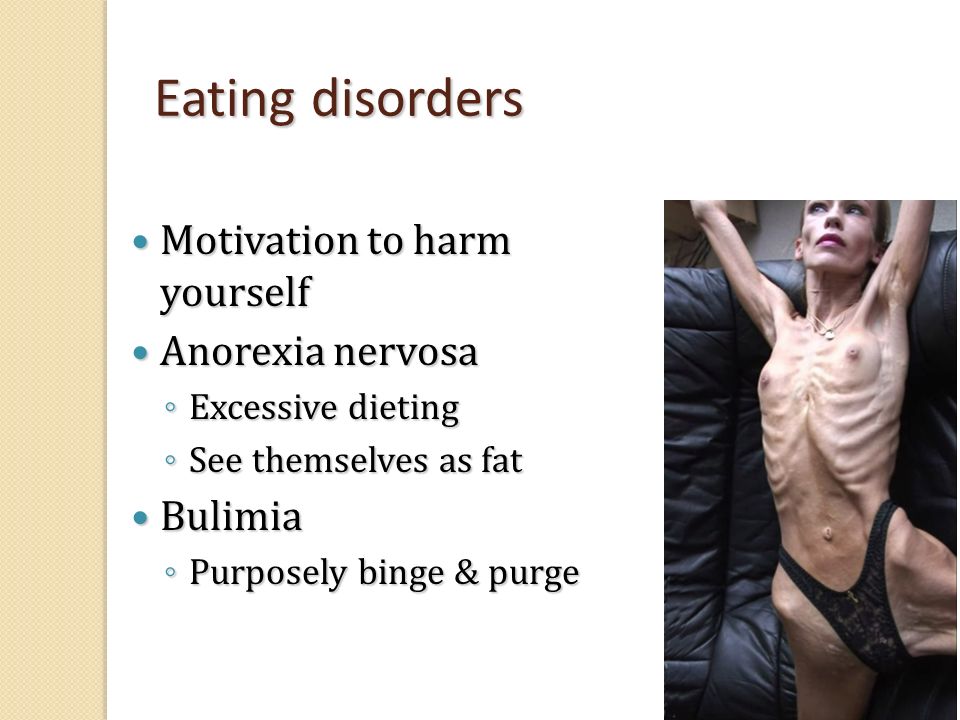

There is no unified classification system for eating disorders, but in psychiatric and neurological practice, more or less similar groups of disorders are described: external, emotional, and restrictive eating behavior [5]. The first two types are classified as binge eating disorders. The third category of disorders is considered by psychiatric practice as a wide range of conditions from anorexia nervosa to bulimia nervosa. nine0003

External eating behavior is manifested by an increased reaction of the patient to external stimuli: a set table, a person eating food, food advertising, etc. With this type of eating behavior, people use every opportunity to have a bite and do not stop until the source of the product runs out, then eat take food whenever it is available to them. The basis of such a response to external stimuli is not only increased appetite, but also a slowly emerging, inferior feeling of satiety. nine0003

With this type of eating behavior, people use every opportunity to have a bite and do not stop until the source of the product runs out, then eat take food whenever it is available to them. The basis of such a response to external stimuli is not only increased appetite, but also a slowly emerging, inferior feeling of satiety. nine0003

In case of emotional eating behavior, the stimulus for eating is not hunger, but emotional discomfort: a person “eats” his troubles. Emotional eating behavior can be represented by a paroxysmal form (compulsive eating behavior) or overeating with a violation of the daily rhythm of eating (night eating syndrome).

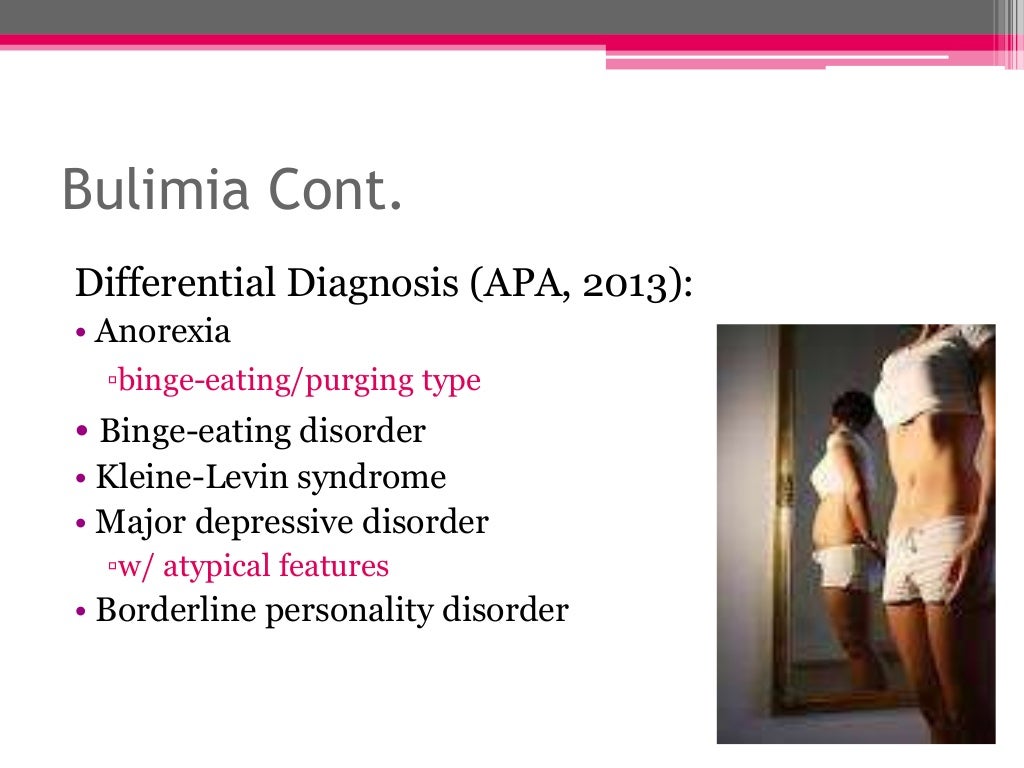

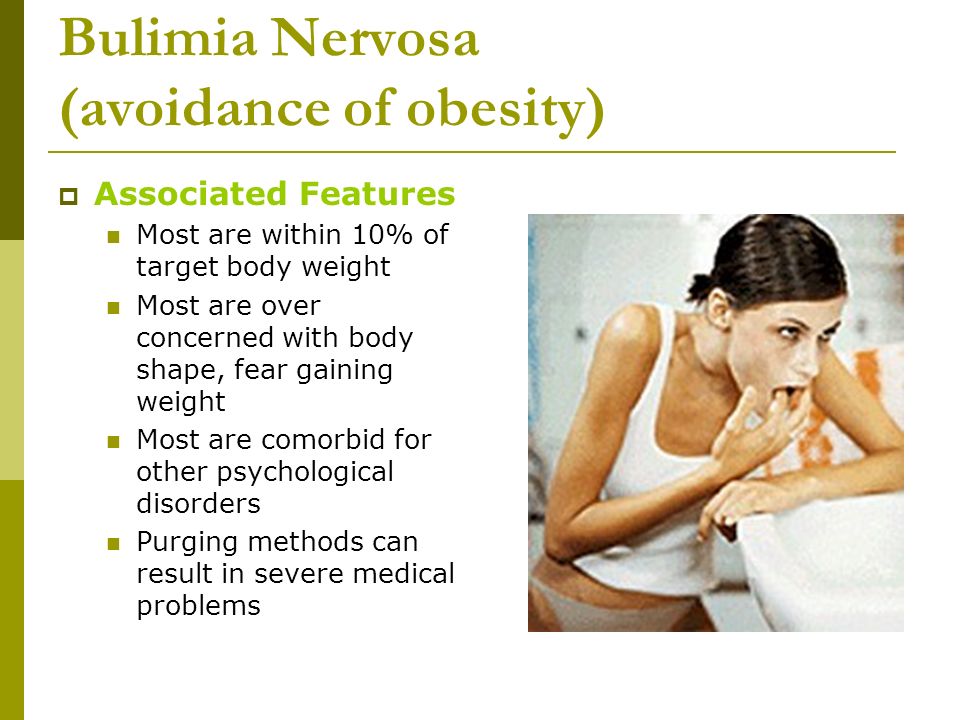

Restrictive eating disorders are characterized by marked preoccupation with body weight and shape, and excessive attempts to control them [6]. The behavioral picture of anorexia nervosa looks like a conscious refusal of food, often in connection with the belief in excessive fullness. Bulimia nervosa is defined by repeated bouts of binge eating with excessive preoccupation with weight control, leading the sufferer to take measures such as inducing vomiting. nine0003

nine0003

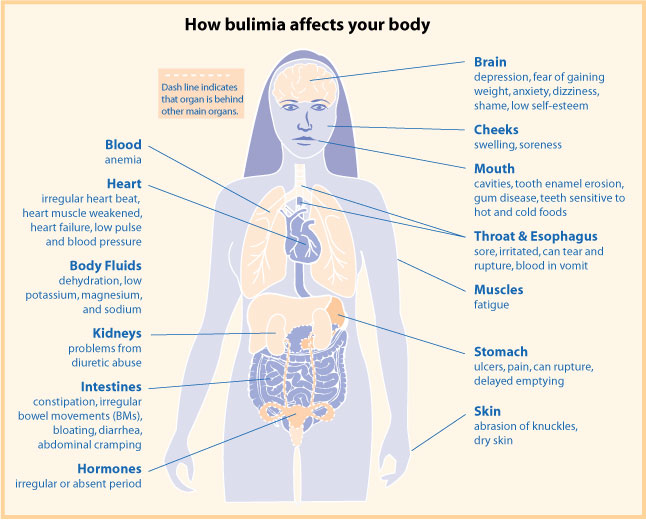

Eating disorders are closely related to endocrine and gynecological pathology. Overeating and the resulting obesity contribute to the development of menstrual dysfunction, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Anorexia nervosa, leading to weight loss, is one of the main causes of secondary amenorrhea and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism [7]. Bulimia nervosa can accompany dysmenorrhea, hyperandrogenism, PCOS, insulin resistance, and visceral obesity. All types of eating disorders often occur or worsen during the premenstrual period. nine0003

Numerous studies on the analysis of food diaries in patients with PMS have shown that their consumption of foods with high energy value differs in different phases of the cycle, being higher in the luteal than in the follicular phase. This is partly due to a worsening of mood before menstruation, which may be due to a physiological mechanism that ensures the accumulation of energy substrates on the eve of a probable pregnancy. Satisfaction of such a basic need as the consumption of "favorite" food improves the overall psycho-emotional state, regardless of the presence or absence of PMS. When comparing 59In patients suffering from PMDD and 60 healthy women, an increase in body mass index on the eve of menstruation was found in both groups, as well as an increase in appetite, a desire to consume foods rich in easily digestible carbohydrates, and an improvement in mood from a high-calorie meal [8].

When comparing 59In patients suffering from PMDD and 60 healthy women, an increase in body mass index on the eve of menstruation was found in both groups, as well as an increase in appetite, a desire to consume foods rich in easily digestible carbohydrates, and an improvement in mood from a high-calorie meal [8].

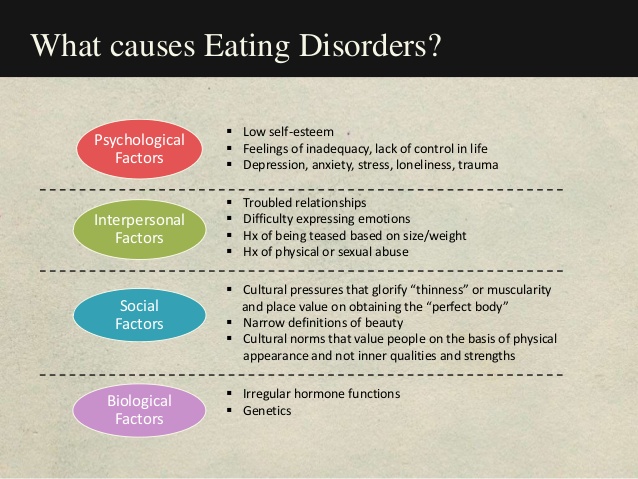

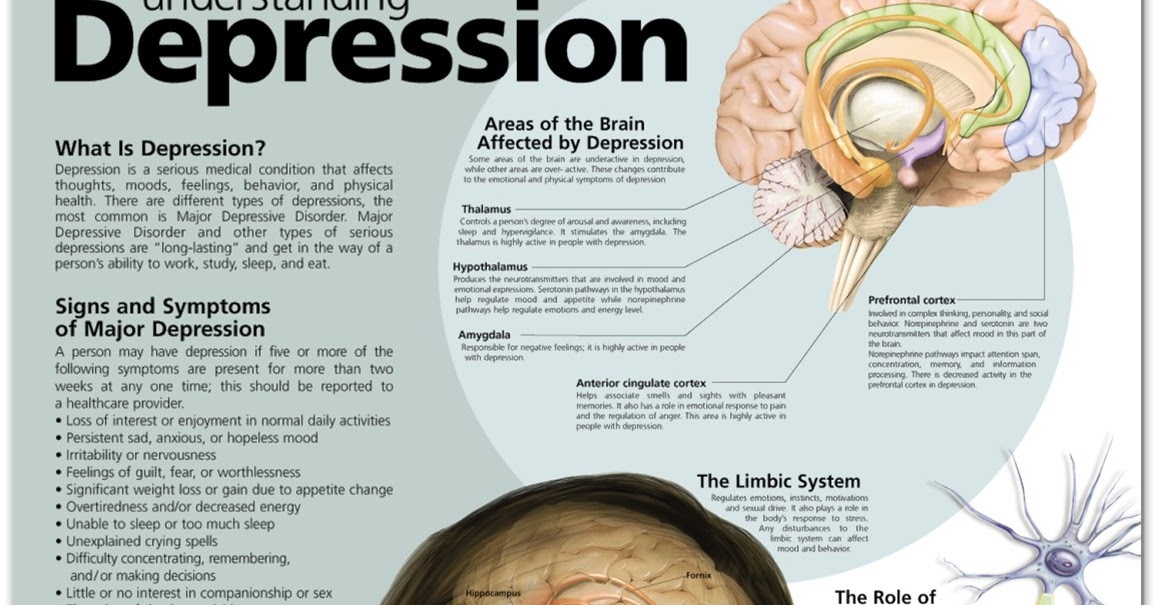

The association of PMS/PMDD with changes in appetite and eating disorders can be explained by several mechanisms, for example, elimination of endogenous opioids, changes in melatonin activity, fluctuations in leptin levels. From hormonal disorders, changes in the content of progesterone and its metabolites, especially alloprenenalone, in the central nervous system (CNS), changes in the ratios of progesterone / estrogens, progesterone / androgens in the luteal phase of the cycle, abnormal response of peptides of the gastrointestinal tract and neuropeptides to hormonal fluctuations are also considered. The relationship between hormonal and mental alterations becomes clearer when studying the features of the formation of eating behavior in normal and pathological conditions [9].

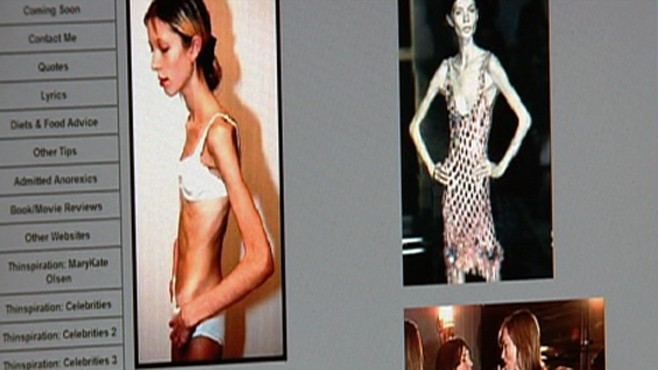

Nutritional need belongs to the category of primary, homeostatic, vital human needs. Food motivation has the features of a hereditarily determined instinctive behavior and is simultaneously associated with the psychology of motivated behavior in general, as well as with social factors. Evolutionarily, in human behavior, a love for foods containing carbohydrates and fats, that is, for the most beneficial, energy-intensive nutrients, has been entrenched. In the ancient world, carbohydrates and fats were difficult to obtain, and in the face of a constant risk of hunger, the human body developed calorie conservation tools, among which a mechanism was formed to improve mood when consuming fatty and sweet foods [10]. In modern developed countries, the risk of malnutrition has been eliminated. With funds, a person can, without physical effort, get as many carbohydrate and fat-containing foods as he wants, that is, containing obviously more calories than he can spend. The advertising of harmful products (mayonnaise, carbonated water, juices, etc. ) reinforces this path to obesity. On the other hand, in modern society, the image of female attractiveness is formed on the basis of a thin to exhaustion model, which traumatizes the psyche of young women, leading to anorexia nervosa and bulimia. So psychosocial factors cause eating disorders. nine0003

) reinforces this path to obesity. On the other hand, in modern society, the image of female attractiveness is formed on the basis of a thin to exhaustion model, which traumatizes the psyche of young women, leading to anorexia nervosa and bulimia. So psychosocial factors cause eating disorders. nine0003

Psychoneuroendocrine regulation of eating behavior is quite complex, especially in the context of hormonal control of the menstrual cycle. The parasympathetic, sympathetic, and serotonergic systems control the interaction between the digestive system, adipose tissue, and the CNS. The mechanisms of nervous regulation involve ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, peptide YY, cholecystokinin, leptin, anorexigenic obestatin, dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, and neutralizing autoantibodies [9]. The signals of satiety and hunger, as well as the mental and physical components associated with them, play a primary role in the pathogenesis of eating disorders [11]. Neuroendocrine dysregulation of the peptides that mediate these signals leads to food perversion. Since sex steroids are able to modulate the secretion of neuropeptides, fluctuations in their levels can cause changes in eating behavior. nine0003

Since sex steroids are able to modulate the secretion of neuropeptides, fluctuations in their levels can cause changes in eating behavior. nine0003

Traditionally, the interaction of estrogens with brain structures involves the binding of this group of steroids to receptors in the nuclei of the hypothalamus, but over time, new areas of action of estrogens and their new effects are being revealed. Thus, the effect of estradiol on the sympathetic nervous system is confirmed by the inhibition of the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, which is involved in the metabolism of catecholamines. In addition, estrogens increase the density and function of type 2 adrenergic receptors located on adipocytes. In turn, the influence of the sympathetic nervous system on energy balance and feeding behavior is known from the opposite: a reduction in sympathetic activity leads to weight gain in both animals and humans [12]. nine0003

In general, estrogens influence eating behavior by stimulating satiety [13]. In women with a regular menstrual cycle, appetite is inversely related to the level of estradiol in the blood, sharply decreasing in the periovulatory period and increasing in the luteal phase. The effect of estradiol on feeding behavior is confirmed by studies on rabbits subjected to ovariectomy, after which the need for excess food saturation increases significantly [14]. The interrelation of fluctuations in the balance of sex hormones with daily energy consumption and caloric content of the food taken has also been demonstrated. Thus, in women of reproductive age in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, against the background of high concentrations of progesterone, body weight, the total amount of food consumed and the fat content in it increase. At the same time, testosterone influences eating behavior, increasing appetite and at the same time selectively increasing the content of high-calorie foods in the diet, but not the size of each individual portion, like progesterone. nine0003

In women with a regular menstrual cycle, appetite is inversely related to the level of estradiol in the blood, sharply decreasing in the periovulatory period and increasing in the luteal phase. The effect of estradiol on feeding behavior is confirmed by studies on rabbits subjected to ovariectomy, after which the need for excess food saturation increases significantly [14]. The interrelation of fluctuations in the balance of sex hormones with daily energy consumption and caloric content of the food taken has also been demonstrated. Thus, in women of reproductive age in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, against the background of high concentrations of progesterone, body weight, the total amount of food consumed and the fat content in it increase. At the same time, testosterone influences eating behavior, increasing appetite and at the same time selectively increasing the content of high-calorie foods in the diet, but not the size of each individual portion, like progesterone. nine0003

The choice of foods rich in carbohydrates is largely due to a pleasant increase in the production of serotonin for the psyche. An increase in the level of serotonin leads to an improvement in the mood and general well-being of women just in the premenstrual period, when patients with PMS experience a significant decrease in the level of the neurotransmitter associated with depression. Thus, women unconsciously choose the foods they need to maintain their psycho-emotional state. The outcome of such food preferences may be an emotional eating disorder with progressive weight gain. nine0003

An increase in the level of serotonin leads to an improvement in the mood and general well-being of women just in the premenstrual period, when patients with PMS experience a significant decrease in the level of the neurotransmitter associated with depression. Thus, women unconsciously choose the foods they need to maintain their psycho-emotional state. The outcome of such food preferences may be an emotional eating disorder with progressive weight gain. nine0003

There is reason to believe that sex hormones affect the metabolism and receptors of neuropeptides, in addition to the ability to act directly on the CNS or participate in metabolic processes occurring in adipose tissue. The largest number of such observations relates to leptin.

Leptin is known to inhibit orexigenic (NPY/AgRP) and stimulate anorexigenic (POMC/CART) receptors in the hypothalamus [15]. Estrogens and androgens are able to influence the secretion of leptin. Experiments on rodents and studies of human tissues have revealed leptin receptors in the ovaries and an increase in leptin production by adipocytes under the influence of estradiol. At the same time, a weakening effect of testosterone on anorexigenic POMC/CART neurons in the arcuate nuclei of the hypothalamus was found [16]. On the other hand, the level of leptin directly depends on the concentration of testosterone in the blood plasma, but this dependence has been demonstrated in obese PCOS patients, for whom hyperandrogenism and hyperleptinemia are typical. Therefore, it is premature to assert the presence of a direct effect of testosterone on leptin secretion. nine0003

At the same time, a weakening effect of testosterone on anorexigenic POMC/CART neurons in the arcuate nuclei of the hypothalamus was found [16]. On the other hand, the level of leptin directly depends on the concentration of testosterone in the blood plasma, but this dependence has been demonstrated in obese PCOS patients, for whom hyperandrogenism and hyperleptinemia are typical. Therefore, it is premature to assert the presence of a direct effect of testosterone on leptin secretion. nine0003

The role of androgens in the occurrence of restrictive eating disorders such as bulimia nervosa is more understood, and here the biologically active substances of the gastrointestinal tract come to the fore. Two peptides, cholecystokinin and ghrelin, are involved in the regulation of eating behavior as stimulating (ghrelin) and suppressing (cholecystokinin) appetite. Cholecystokinin is secreted by the gut in response to food intake and inhibits feeding activity in animals and humans. Ghrelin, on the other hand, stimulates appetite and is secreted by the gastric mucosa during fasting. In turn, cholecystokinin weakens the appetite-stimulating effect of ghrelin [17]. In bulimia, cholecystokinin levels are reduced and ghrelin levels are elevated [18]. Sex steroids affect the secretion of these peptides. Thus, estradiol potentiates the effects of saturation by increasing the production of cholecystokinin I-cells of the duodenal mucosa and the proximal jejunum in response to food intake. Androgens stimulate appetite, and women with PCOS show a reduction in postprandial secretion of cholecystokinin associated with increased testosterone levels [19]. This allows us to consider hyperandrogenism as one of the factors of eating disorders in women. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the use of the androgen receptor antagonist flutamide leads to a reduction in symptoms in patients with bulimia [20].

In turn, cholecystokinin weakens the appetite-stimulating effect of ghrelin [17]. In bulimia, cholecystokinin levels are reduced and ghrelin levels are elevated [18]. Sex steroids affect the secretion of these peptides. Thus, estradiol potentiates the effects of saturation by increasing the production of cholecystokinin I-cells of the duodenal mucosa and the proximal jejunum in response to food intake. Androgens stimulate appetite, and women with PCOS show a reduction in postprandial secretion of cholecystokinin associated with increased testosterone levels [19]. This allows us to consider hyperandrogenism as one of the factors of eating disorders in women. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the use of the androgen receptor antagonist flutamide leads to a reduction in symptoms in patients with bulimia [20].

There are other factors that modify eating behavior in women. These include increased secretion of thyroid-stimulating hormone in response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone, reduced duration of slow-wave sleep, altered melatonin secretion, reduction in plasma b-endorphin levels, reduced secretion of growth hormone and cortisol in response to L-tryptophan, as well as their increased secretion in response to the introduction of corticotropin-releasing hormone, indicating an altered stress response. An increase in the concentration of prolactin affects eating behavior in the form of an increase in food intake. A similar result has a decrease in the time of night sleep. nine0003

An increase in the concentration of prolactin affects eating behavior in the form of an increase in food intake. A similar result has a decrease in the time of night sleep. nine0003

There are non-drug and drug treatments for PMS and eating disorders. Given the heterogeneity of the manifestations of the syndrome and the significant contribution of the mental component to its pathogenesis and clinical picture, physicians should remember the advisability of a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of such patients.

Much research has been done on the effectiveness of psychological treatments. These can be divided into lifestyle modifications such as diet modification, relaxation and exercise programs, and specific psychotherapeutic approaches such as support groups and cognitive behavioral therapy. nine0003

Dietary recommendations aimed at maintaining the homeostasis of the organism under stress and improving adaptive capabilities exist and are constantly being improved [21]. Dietary modifications suggested for PMS patients include reducing salt, unrefined sugar, caffeinated foods, and alcohol. Frequently eating small, carbohydrate-rich snacks can increase tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin, and an increase in serotonin has a positive effect on mood. Clinical studies evaluating the effectiveness of dietary changes have shown positive results, but most of these studies have been uncontrolled. nine0003

Dietary modifications suggested for PMS patients include reducing salt, unrefined sugar, caffeinated foods, and alcohol. Frequently eating small, carbohydrate-rich snacks can increase tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin, and an increase in serotonin has a positive effect on mood. Clinical studies evaluating the effectiveness of dietary changes have shown positive results, but most of these studies have been uncontrolled. nine0003

Relaxation training is a useful addition to the PMS behavioral therapy package. But research data confirming its independent effectiveness is still insufficient. Physical exercises have been studied to a greater extent. The combination of diet and exercise is especially important for overweight women, as it helps to balance the energy balance, and weight loss itself has a beneficial effect on the psychological state of patients [22]. But regardless of body weight, women who regularly play sports are less likely to complain before menstruation. In a six-month prospective follow-up, in sedentary women, exercise has been shown to positively affect mood symptoms, reduce fluid retention, and reduce breast tenderness. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of women with confirmed PMS, aerobic exercise was also evaluated positively, but intensive exercise was more effective. It remains unclear, however, whether the improvement caused by exercise is the result of physiological or psychological changes. nine0003

In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of women with confirmed PMS, aerobic exercise was also evaluated positively, but intensive exercise was more effective. It remains unclear, however, whether the improvement caused by exercise is the result of physiological or psychological changes. nine0003

The description of the model of cognitive-behavioral therapy for PMS was successfully borrowed from the well-established techniques of this method of psychotherapy, which is also used in gynecological practice [23]. The reason for this extrapolation was the assumption that women with PMS can negatively interpret the physiological changes taking place in the body. Repeated expectation of negative experiences increases anxiety and depression, especially against the background of existing psychosocial stressors. Expected somatic changes disrupt normal coping mechanisms, which are seen as out of control, and further increase apprehension and anxiety, causing a sense of imminent loss of control. A vicious circle of negative thoughts and self-deprecating behavior supports a maladaptive response to physiological changes. Of particular importance are early experiences of criticism, which contribute to the formation of rigid standards of behavior and actions and do not allow moderate fluctuations in well-being. When such fluctuations occur, they may be accompanied by maladaptive responses [24]. Using the cognitive behavioral therapy model involves trying to find adaptive ways to cope with premenstrual changes. nine0003

A vicious circle of negative thoughts and self-deprecating behavior supports a maladaptive response to physiological changes. Of particular importance are early experiences of criticism, which contribute to the formation of rigid standards of behavior and actions and do not allow moderate fluctuations in well-being. When such fluctuations occur, they may be accompanied by maladaptive responses [24]. Using the cognitive behavioral therapy model involves trying to find adaptive ways to cope with premenstrual changes. nine0003

The use of cognitive behavioral therapy in patients with PMS has shown mixed results. Short-term interventions of four or fewer sessions have not been effective, but comparative studies have shown that CBT-based interventions were more successful than support groups, relaxation, and dydrogesterone in the luteal phase of the cycle. As expected, CBT was particularly effective for negative thought content, self-blame, and avoidance. Unfortunately, there are no studies comparing cognitive behavioral therapy with optimal drug treatment for PMS, such as combined oral contraception, claimed as a therapeutic option for correcting PMS, GnRH agonists, etc.

Overweight patients with reduced satiety, emotional eating behavior accompanied by anxiety and depressive disorders, panic attacks, as well as patients with bulimia nervosa are offered antidepressants: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [25]. Fluoxetine is prescribed in a daily dose of 20 to 60 mg for three months, fluvoxamine in a daily dose of 50 to 100 mg per day also for three months. The same drugs are recommended for patients with PMDD, but their effect on long-term retention of body weight, as well as the reduction of symptoms of less severe PMS in terms of mental manifestations, has not been proven. nine0003

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) play a special role in the treatment of PMS and PMDD, among which COCs with drospirenone (DRSP-COCs), such as midian or dimia, are considered the best therapy option (they have an annotated indication - contraception in patients with PMS). The effectiveness of DRSP-COCs in the treatment of PMS/PMDD has been proven in double-blind RCTs [26, 27]. But the properties of DRSP-COC in the correction of eating disorders are underestimated.

But the properties of DRSP-COC in the correction of eating disorders are underestimated.

Drospirenone, a derivative of spirolactone, is the closest "relative" of spironolactone, known not only as a potassium-sparing diuretic and mild antihypertensive agent, but also as a steroid that has the ability to reduce the manifestations of bulimic behavior in women in the luteal phase of the cycle [15]. This feature of spironolactone has been found in drospirenone and is usually attributed to the antiandrogenic effects of steroids. nine0003

As already mentioned, endogenous cholecystokinin and ghrelin are involved in the implementation of the effect of antiandrogens on the centers of eating behavior. When using DRSP-COC, women with impaired and normal eating behavior observed a different reaction of cholecystokinin secretion. In patients with bulimia, there is an increase in the level of the peptide, while in healthy women, the use of COCs is accompanied by a decrease in the secretion of cholecystokinin. Ghrelin secretion does not change during the use of COCs [28]. It is likely that the increase in appetite and the change in eating habits noted by some healthy women during the use of COCs is associated precisely with a decrease in the level of cholecystokinin. Such a reaction to a contraceptive can lead to weight gain, but when using DRSP-COC (midian, dimia), this tendency is leveled by the antimineralocorticoid effect of the drug. The results of double-blind RCTs on the efficacy and safety of DRSP-COCs in comparison with other combined hormonal contraceptives showed that taking DRSP-COCs promotes weight loss [29–31]. The use of DRSP-COC for 6–12 months was accompanied by weight reduction, followed by stabilization and no return to baseline. According to some data, 15.3% of patients have a decrease in body weight by the end of the 6th cycle of admission by 3.5–4.5 kg, and only 2.8% show weight gain by 1.8–2.3 kg [32].

Ghrelin secretion does not change during the use of COCs [28]. It is likely that the increase in appetite and the change in eating habits noted by some healthy women during the use of COCs is associated precisely with a decrease in the level of cholecystokinin. Such a reaction to a contraceptive can lead to weight gain, but when using DRSP-COC (midian, dimia), this tendency is leveled by the antimineralocorticoid effect of the drug. The results of double-blind RCTs on the efficacy and safety of DRSP-COCs in comparison with other combined hormonal contraceptives showed that taking DRSP-COCs promotes weight loss [29–31]. The use of DRSP-COC for 6–12 months was accompanied by weight reduction, followed by stabilization and no return to baseline. According to some data, 15.3% of patients have a decrease in body weight by the end of the 6th cycle of admission by 3.5–4.5 kg, and only 2.8% show weight gain by 1.8–2.3 kg [32].

In initially disturbed eating behavior, the response to taking DRSP-COC is fundamentally different, and the central mechanisms that modify eating behavior are responsible for weight loss in case of its excess, as a result of which food intake decreases. Increasing secretion of cholecystokinin stimulates anorexigenic centers, reducing appetite and reducing the frequency of bulimic attacks. But it is difficult to fully attribute such an effect of drospirenone to the antiandrogenic effect. Other antiandrogenic progestins have not been seen to have such a favorable effect on eating behavior, which suggests that not only the antiandrogenic, but also the antialdosterone effect is involved in this process. Some studies have shown a decrease in gastrin production with the use of DRSP-COCs in women with bulimia nervosa. Thus, it should be recognized that the effect of drospirenone on the regulation of eating behavior and fat metabolism has not been fully studied. nine0003

Increasing secretion of cholecystokinin stimulates anorexigenic centers, reducing appetite and reducing the frequency of bulimic attacks. But it is difficult to fully attribute such an effect of drospirenone to the antiandrogenic effect. Other antiandrogenic progestins have not been seen to have such a favorable effect on eating behavior, which suggests that not only the antiandrogenic, but also the antialdosterone effect is involved in this process. Some studies have shown a decrease in gastrin production with the use of DRSP-COCs in women with bulimia nervosa. Thus, it should be recognized that the effect of drospirenone on the regulation of eating behavior and fat metabolism has not been fully studied. nine0003

Undoubtedly, changes in eating behavior are only part of the central modifying effects of COCs with drospirenone. Further study of these effects should be of interest not only to gynecologists, but also to specialists who specifically study the nervous system psychiatrists, neurologists, and psychoneuroendocrinologists. A comprehensive study of hormonal contraception from the standpoint of its impact on the psyche, behavior and autonomic reactions will help identify new directions in the treatment of PMS/PMDD and other maladaptive syndromes. nine0003

A comprehensive study of hormonal contraception from the standpoint of its impact on the psyche, behavior and autonomic reactions will help identify new directions in the treatment of PMS/PMDD and other maladaptive syndromes. nine0003

1. Villarejo C., Fernández-Aranda F., Jiménez-Murcia S., Peñas-Lledó E., Granero R., Penelo E. et al. Lifetime obesity in patients with eating disorders: increasing prevalence, clinical and personality correlates. Eur. EatDiscord. Rev. 2012; 20(3): 250-4.

2. Yonkers K.A., O'Brien P.M., Eriksson E. Premenstrual syndrome. Lancet. 2008; 371(9619): 1200-10.

3. Reed S.C., Levin F.R., Evans S.M. Changes in mood, cognitive performance and appetite in the late luteal and follicular phases of the menstrual cycle in women with and without PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder). Horm. behavior. 2008; 54(1): 185-93.

4. Di Giulio G., Reissing E.D. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: prevalence, diagnostic considerations, and controversies. J. Psychosom. obstet. Gynaecol. 2006; 27(4): 201-10.

obstet. Gynaecol. 2006; 27(4): 201-10.

5. Thomas J.J., Vartanian L.R., Brownell K.D. The relationship between eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) and officially recognized eating disorders: meta-analysis and implications for DSM. Psychol. Bull. 2009; 135(3): 407-33.

6. Eddy K.T., Dorer D.J., Franko D.L., Tahilani K., Thompson-Brenner H., Herzog D.B. Diagnostic crossover in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: implications for DSM-V. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008; 165(2): 245-50. nine0099 7. Miller K.K. Endocrine dysregulation in anorexia nervosa update. J.Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011; 96(10): 2939-49.

8. Yen J.Y., Chang S.J., Ko C.H., Yen C.F., Chen C.S., Yeh Y.C., Chen C.C. The high-sweet-fat food craving among women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: emotional response, implicit attitude and rewards sensitivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010; 35(8): 1203-12.

9. Keen-Rhinehart E., Ondek K., Schneide J.E. Neuroendocrine regulation of appetitive ingestive behavior. Neuroendocr. sci. 2013; 7:13.

Neuroendocr. sci. 2013; 7:13.

10. Sudo N., Degeneffe D., Vue H., Ghosh K., Reicks M. Relationship between needs driving eating occasions and eating behavior in midlife women. Appetite. 2009; 52(1): 137-46.

11. Smitka K., Papezova H., Vondra K., Hill M., Hainer V., Nedvidkova J. The role of "mixed" orexigenic and anorexigenic signals and autoantibodies reacting with appetite-regulating neuropeptides and peptides of the adipose tissue -gut-brain axis: relevance to food intake and nutritional status in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013; 2013: 483145.

12. Jocken J.W.E., Blaak E.E. Catecholamine-induced lipolysis in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in obesity. physiol. behavior. 2008; 94:219-30.

13. Santollo J., Katzenellenbogen B.S., Katzenellenbogen J.A., Eckel L.A. Activation of ER is necessary for estradiol's anorexigenic effect in female rats. Horm. behavior. 2010; 58:872-7.

14. Butera P.C. Estradiol and the control of food intake. physiol. behavior. 2010; 99:175-80.

physiol. behavior. 2010; 99:175-80.

15. Hirschberg A.L. Sex hormones, appetite and eating behavior in women. Maturitas. 2012; 71(3): 248-56. nine0099 16. Nohara K., Zhang Y., Waraich R.S., Laque A., Tiano J.P., Tong J. et al. Early-life exposure to testosterone programs the hypothalamic melanocortin system. endocrinology. 2011; 152(4): 1661-9.

17. Clegg D.J., Brown L.M., Zigman J.M., Kemp C.J., Strader A.D., Benoit S.C. et al. Estradiol-dependent decrease in the orexigenic potency of ghrelin in female rats. diabetes. 2007; 56(4): 1051-8.

18. Monteleone P., Fabrazzo M., Tortorella A., Martiadis V., Serritella C., Maj M. Circulating ghrelin is decreased in non-obese and obese women with binge eating disorder as well as in obese non-binge eating women, but not in patients with bulimia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005; 30(3): 243-50. nine0099 19. Hirschberg A.L., Naessén S., Stridsberg M., Byström B., Holtet J. Impaired cholecystokinin secretion and disturbed appetite regulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2004; 19(2): 79-87.

Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2004; 19(2): 79-87.

20. Sundblad C., Landén M., Eriksson T., Bergman L., Eriksson E. Effects of the androgen antagonist flutamide and the serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram in bulimia nervosa: a placebo-controlled pilot study. J.Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2005; 25(1): 85-8.

21. Reynolds C.J., Buckley J.D., Weinstein P., Boland J. Are the dietary guidelines for meat, fat, fruit and vegetable consumption appropriate for environmental sustainability? A review of the literature. Nutrients. 2014; 6(6): 2251-65. nine0099 22. Wadden T., Butryn M., Byrne K. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. obes. Res. 2004; 12(Suppl.): 151S-62S.

23. Berga S.L., Loucks T.L. Use of cognitive behavior therapy for functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Ann. N. Y. Acad. sci. 2006; 1092:114-29.

24. Tovsultanova M.S. Some aspects of complex therapy of social stress disorders. In: Collection of abstracts of the III scientific-practical conference with international participation "Vegetative disorders in the clinic of nervous and internal diseases". M.; 2010: 61.

M.; 2010: 61.

25. Wayne A.M., Voznesenskaya T.G. Depression in neurological practice. M.: MIA; 2007. 265 p.

26. Yonkers K.A., Brown C., Pearlstein T.B., Foegh M., Sampson-Landers C., Rapkin A. Efficacy of a new low-dose oral contraceptive with drospirenone in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. obstet. Gynecol. 2005; 106(3): 492-501.

27. Pearlstein T.B., Bachmann G.A., Zacur H.A., Yonkers K.A. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with a new drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive formulation. contraception. 2005; 72(6): 414-21. nine0099 28. Naessen S., Carlström K., Byström B., Pierre Y., Hirschberg A.L. Effects of an antiandrogenic oral contraceptive on appetite and eating behavior in bulimic women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007; 32(5): 548-54.

29. Bertolini S., Elicio N., Cordera R., Gapitanio G. L., Montagna G., Croce S. et al. Effects of three low-dose oral contraceptive formulations on lipid metabolism. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007; 66(4): 327-32.

30. Gallo M.F., Lopez L.M., Grimes D.A., Schulz K.F., Helmerhorst F.M. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008; (4): CD003987.

31. Krattenmacher R. Drospirenone: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of unique progestogen. contraception. 2006; 41:875-86.

32. Basova O.N., Volkov V.G. Experience with the use of a combined oral contraceptive containing drospirenone. In: Materials of the X Anniversary All-Russian Scientific Forum "Mother and Child". M.; 2009: 259-60.

Kuznetsova Irina Vsevolodovna, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Senior Researcher Research Center for Research and Development of Women's Health of the First Moscow State Medical University. THEM. Sechenov. Address: 119991, Russia, Moscow, st. Trubetskaya, d. 8, building 2. Phone: 8 (985) 287-09-09. E-mail: [email protected]

Dil Victoria Valerievna, Postgraduate Student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Research Center for Women's Health, First Moscow State Medical University. THEM. Sechenov. Address: 119991, Russia, Moscow, st. Trubetskaya, 8, building 2. Phone: 8 (916) 280-02-33. E-mail: [email protected]

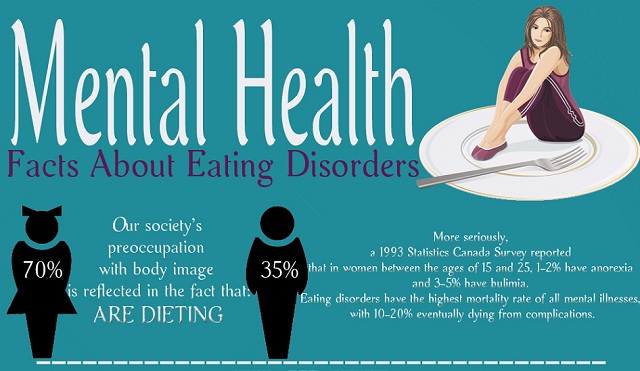

| The Beauty Myth Naomi Wolf I had the opportunity to learn about thousands of real life stories. In letters and conversations, women told me about the difficulties they had to go through in order to get rid of the oppression of what they called "the myth about beauty" as a result of a difficult internal struggle. In terms of appearance between these women we had nothing in common. Young and not so young, they said that they were afraid of growing old; both thin and plump people tell how much they had to endure in order to live up to the ideal of harmony; representatives of different races, including women with a model appearance, admitted that they always knew that the ideal of beauty is a tall, slender blonde with regular features and flawless skin, in other words, a "perfect" creature that they felt they were not. I am grateful to fate that I was lucky enough to write a book that enriched my life experience with the experience of other women living in various parts of our planet, to be exact, in 17 countries of the world. But even more, I am grateful to fate for the fact that my book turned out to be useful to female readers. I often heard from them: “Your book helped I can get rid of my eating disorder”, “Now I read women's magazines in a completely different way”, “I stopped not seeing my legs, which used to seem to me crow's feet”. My book has helped many women gain inner strength and self-confidence, see through and destroy their own beauty myths . Not only did this book resonate with a wide range of readers women of all backgrounds and social status, but also caused a great public outcry. Female TV presenters took up arms against me for saying that their salaries directly depend on their external data. argued that since I couldn't conform to the idea of what a woman should look like, there must be something wrong with me. And the journalists who interviewed me hinted that my concern was the problem of anorexia is nothing but a consequence of the psychological drama of a white girl from a privileged family who has not found her place in life. every show I went to, the questions addressed to me sounded almost hostile, and it is possible that the reason for this was the impact of the advertising broadcast after the show, paid for by the multi-billion dollar beauty industry. Often comments - the tori deliberately or accidentally, but always without reason accused me of allegedly calling on women not to shave their legs and not to wear lipstick. In fact, this is not the case, because what I really advocate in my book is the right of a woman to choose how she wants to look and be, and not to obey the laws dictated by the market economy and advertising industry. One got the impression that radio listeners and television 3the audience (albeit to a greater extent in public than in private) thought that questioning the ideals of beauty was not only unfeminine, but unpatriotic, even somehow un-American . In the 21st century it may be difficult for the reader to believe this, but then, in 1991, it seemed unacceptable to challenge the ideal of beauty . In those years, we were just coming to our senses after a period that I called "the cruel eighties", when in our culture pronounced conservatism was closely intertwined with strong anti-feminism, which made the discussion of the ideals of femininity a sign of bad manners and even eccentricity. The presidential term of Ronald Reagan had just ended, the Equal Rights Amendment had not been ratified, the women's all at once". As she very accurately noted in her Backlash by Susan Faludi, Newsweek magazine convinced women that they were much more likely to die at the hands of terrorists than to be married at the peak of careers. that women, dissatisfied with the notions of beauty that were imposed on them by society, were themselves far from perfect : they were fat, ugly, unable to satisfy 0004 a man, "Nazis in a skirt" or even - oh horror! — lesbians. The ideal of that time - a slender and at the same time full-breasted woman of the white race, which is not often found in nature - was accepted as eternal and unchanging not only by the media , but also - often - by readers and television viewers. And it seemed undeniably important to try to live up to this ideal. When I said in my public speeches, example, about the epidemic of eating disorders or about the dangers of silicone breast implants, I was often answered with quotes from Plato's "Feast", saying something like : "Women have always suffered in the name of beauty." In other words, at that time there was not yet a general understanding that the ideals of beauty do not just fall from the sky, that in fact they are created by someone, and they are created with a very specific purpose. explain that there is often money, or rather, an increase in profits advertisers who pay money to the media , who, in turn, create the necessary ideals. I argued that the ideal of beauty also serves political purposes . The stronger the position women

0004 direct their energy in a different direction, stopping their movement forward. And how is it now, 10 years later? What is the beauty myth today? It has changed somewhat, , and therefore you can look at it with a fresh look. The good news is that in our time it is already difficult to find a 12-year-old girl who would not understand that the “ideals” are too heavy a burden on the girls. They're unnatural0003 and blindly, slavishly following them is not only unhealthy, but also not cool at all. American Girl magazine, whose target audience is nine-year-old girls, teaches you to treat your body with love and explains that trying to look like Britney Spears will not make you happy. specialists to lecture on eating disorders and put up 9 posters in the corridors.0004 pernicious and destructive influence of beauty myths. Ideasoriginally perceived as a controversial opinion of out- siders have become accepted views, and this is certainly a sign of evolution of consciousness. The time has come: girls and women are ready to say "no" to what they regard as tyranny . This is clear progress. However, despite this recent trend, I have noticed that the ideal of female beauty is becoming more and more sexy, and girls of ever younger age feel compelled to conform to it. When I was a teenager, Calvin Klein's sensational advertising campaigns portrayed in the erotic light of 16-year-old models. In the early 1990s they were replaced by 14-year-olds, and at the end of the century - 12-year-olds. Now nine-year-old models in provocative and seductive poses are being filmed in GUESS Jeans advertising. fashion samples for seven- and eight-year-old girls recreate the outfits of pop stars who dress like sorry tutki. And this is called progress? I doubt. Many of the high school and college projects I know of, ranging from CDs on how to "look good" to dissertations on the African American beauty myth , analyzed media-created ideals female images and debunked them. Even pop culture from- clicked on women's concern about this problem: take meme, for example, the TLC music video for the song "Ugly" (Unpretty), in which a woman is ready to go to breast surgery just to please her boyfriend. But then she still decides that it is not worth doing this . And yet, despite the fact that the book The Beauty Myth has helped many girls and women to critically evaluate the ideals created by mass culture, this achievement can be can be negated very easily. When this book was first published in 1991, silicone breast implants were common and very common. The influence of porno graphics on popular culture has led to the fact that millions of women began to worry about the size and shape of their breasts. If this seems strange to you, consider how powerfully visual images of sexual havoc affect the psyche.0003 rakter. Due to the influence of pornography on fashion, millions of women constantly and everywhere saw the “perfect breasts” and, naturally, began to worry about their own “imperfect” breasts. Responding to the challenge of the new ideal of beauty, many women began to sign up for breast augmentation . Advertising of silicone implants has created a new advertising market and has become an important source of income for women's magazines that published, in addition to advertising, one article after another about breast surgery. the book "The Beauty Myth" sounded the alarm about the side effects of the effects of silicone on the body and complications after the operations themselves, few women imagined the degree and extent of the threat that threatened them as a result of such a surgical hazard interference. Now, 10 years later, all the risks associated with implantation silicone, documented. Manufacturers of breast implants have been in trouble with the law more than once, and since the mid-1990s, thousands of articles have appeared in the press disclosing the dangers of such operations. By 2000 silicone had almost disappeared from the general market. It is not surprising that today publications on the topic of women's concern about breast size are extremely rare. Why? Because attentive study of the issue led to the initiation of criminal cases and the beginning of judicial investigations. Advertisers no longer pay for articles on this topic, the same articles that once stirred up this concern in women, thus creating an increased demand for silicone implants. That's about a glass half full. And now about the half empty glass. The impact of pornography on women's perception of their sexuality, which was just beginning to spread when this book was first published, has become all-consuming in our time. Therefore, today it is very difficult for young girls to separate the images imposed by pornography from natural impulses and ideas about how to behave, look and move during sex. Is that also called progress? I do not think so. When this book first appeared, there were 9 cases0003 bulimia and anorexia were considered a marginal phenomenon, caused by a personality crisis, unhealthy perfectionism, lack of parental attention and care or other forms of individual psychological disorders. phenomenon, which appeared as a result of the imposition by this very society of the ideals of beauty and the requirements to conform to them. But actually girls from the most ordinary families suffered the most from these diseases, trying to simply fit into the existing limits and keep themselves in an unnatural “ideal” form. Watching what happens in schools and colleges, I realized that eating disorders are widespread among girls with a non-model type of constitution , which at the same time are ideally combined for their natural data, and at the heart of the occurrence and distribution Public pressure lies behind the prevention of these diseases. The American National Association for the Prevention of Eating Disorders cites statistics from the National Institutes of Health that 1-2% of American women suffer from anorexia, which is 1. also emphasize that the mortality rate from 0003 rexii, which amounted to 56% over the past decade, is 12 times higher than the mortality rate among girls aged 15 to 24 from any other cause. Anorexia is the main "killer" of teenage girls. From personal experience of observing women, I know that eating disorders create a vicious cycle. Starvation or artificial induction of vomiting quickly becomes a habit. I know that common public opinion required a girl to be so thin that this sometimes led to a menstrual cycle disorder, and that in order not to deceive the expectations of society, one had to actually bring herself to illness . Unhealthy eating, serving the purpose of achieving an unhealthy ideal, was one of the main causes of the onset of the disease, which was not at all necessary, as public opinion tried to prove at that time, was a consequence of neurosis. Of course, today knowledge about the dangers that threaten with strict diets and excessive exercise is spreading in every way. Information about eating disorders and how to treat them can be found in any bookstore, as well as in high schools, doctors' offices, sports clubs, colleges, and student residences. This is real progress. But on the other hand, now these ailments are so widespread0003

countries have been eliminated — in many respects at the suggestion of the mass media — that they began to be perceived by society almost as the norm of life. Bulimia has become a typical phenomenon not only in female student communities. Fashion girls in their interviews began to talk openly about their fasting regimens. Glamor ran a front-page article about thin and ambitious young women discussing weight issues and quoted one of them:0003 to induce vomiting?” specialized sites have appeared on the Internet for girls who find anorexic appearance attractive and strive to look appropriate. In the early 1990s, when the myth of beauty was first comprehended and analyzed , the ideal of beauty was quite rigid. The faces of older women simply did not appear on the covers of magazines , in extreme cases - after computer processing photos to make them look much younger than their years. Women of color acted as models extremely rarely, with the exception of such as Beverly Johnson - with the features of a white woman. Today, the beauty myth is very pluralistic, one could even say that there are now many varieties of the beauty myth. A 17-year-old African-American black model became the "face of the day" according to the newspaper The New York Times. Benetton's ads feature young people of various races and ethnicities. Fifty-year-old Cybill Shepherd continues to be the cover face, while adored plump model Emmy hosts her own Fashion ER TV show. can freely wear traditional national clothes to work and make traditional ethnic clothes Chescu - they no longer need to constantly straighten their hair, as in the early 1990s. Even the Barbie doll has become more realistic looking and is now available in several versions— different skin colors. We can say that now women have more opportunities to be themselves. In addition, the sphere of protecting the interests of consumers has noticeably developed. Today, manufacturers of anti-aging creams no longer make impossible promises, as they did 10 years ago - ass. Back then, cosmetic companies claimed that their anti-aging creams "destroy" the signs of age-related changes, "restructure" the skin at the "cellular" level, -

it is impossible to lay, because the ingredients of these creams simply cannot penetrate deeper than the epidermis layer. Things went like this so far that in the end the situation had to intervene Food and Drug Administration . At the same time, the FTC took up the hype for diet programs in earnest. She warned advertisers not to mislead people into losing weight once and for all unless they have enough sound research body data supporting the claimed results. The Society for the Protection of Consumer Rights succeeded in removing the production of weight-reducing pills Fen-fen, which caused heart disease , which in some cases led to death . The actions of the Consumer Protection Society and the Federal Trade Commission not only saved women money, but also relieved them of the stress associated with anxiety.0003 with regard to his age. The driving force behind the ads is no longer wrinkle cream manufacturers, but the new consumer opportunities of middle-aged women, the fastest growing segment of the solvent population in the United States. women's magazines, television programs, and even Hollywood directors suddenly discovered that there are a huge number of amazingly charismatic women over 40 years old, of which may well be advertised. of society, women are now less worried about the approach of their 40th or 50th anniversary, they no longer associate the aging process with the inevitable loss of individuality and retain the right in any grow up to remain energetic and sensual, worthy of love and a high lifestyle. the number of “non-standard” complete models is growing rapidly, occupying all a stronger position in the world of fashion and cosmetics. And representatives of the Mongoloid and Negroid races are among the most sought-after "icons" of fashion and cause universal admiration. But does this mean that pluralism has finally now prevailed in the myth of beauty? No. This is far from true. The myth of beauty, like many other ideas about femininity, trans- is formed and adapts to new conditions, striving to freshen up.0003 all attempts by women to strengthen their influence in society come to naught. York Times that she ousted famous actress Renee Zellwe from the cover of Vogue magazine because she became "too fat" when she gained weight for filming the film. "Diary Bridget Jones", that is, it took on the form of an ordinary average woman. The newspapers also suggested that the del Elizabeth Hurley stopped being the face of Estee Lauder, , because at 36 she was "too old" for it. At the same time, the modern average model, in comparison with its “colleagues” from the 1980s and 1990s, is even more thin. In the process of transformation, the beauty myth has drawn men into its sphere of influence as well. True, in relation to the latter its driving force is rather the laws of the market economy.0003 economy than the factors of socio-cultural plan. As I predicted, in the past decade a myth about male beauty emerged. Having gone beyond the homosexual community, it spread to all newsstands of the country and puzzled the fathers of families living in the suburbs with a new problem for them - concern about their bellies, with whom they had previously lived quietly and felt great. suburbanites with toothpaste now invariably Minoxidil*. As a result of the increasing influence of women on the economic and social spheres of life, the gap between the sexes continues to shrink, and men are squeezed out of positions of connoisseurs of sexual attractiveness and beauty. The inevitable consequence of this was an increased demand for Viagra . magazines dedicated to men's fashion, men's health and personal care began to appear. Volume aesthetic surgery services for men broke all previous records. Today they make up a third of the customer market, 90,003 90,004 cosmetic users, and 10% of the 90,003 90,004 college students suffering from eating disorders 90,003 90,004. Nowadays, men of all ages and levels of wealth (regardless of sexual orientation) worry about their appearance much more than some some 10 years ago. But how can you call progress that both sexes are turned into commodities and valued as objects? * Preparation for hair loss. right now is that after 10 years, women have a little more freedom to do what I called them to in the final parts of the book "The Myth of Beauty", namely: to create your own myth of beauty. Today many women feel free enough and independent to dress smartly or casually , wear lipstick or not, dress up, flaunt their bodies, or wear sports jerseys, and even. .. even... sometimes gain weight or lose weight without fear that their female self-esteem or the integrity of their personality will suffer. Not so long ago to make such decisions was much more difficult and scarier. It's hard to believe these days, , that just a decade ago, too many of us were asking questions: “Will I be taken seriously at work if I look “too feminine”?”, “Will I be at all listen if I look too inconspicuous, like a gray mouse?”, “Will I be “bad” if I gain weight?”, “Will I become “good” if I get rid of extra pounds- 0004 mov?". |