Can hrt cause depression and anxiety

Effects of Hormone Therapy on Cognition and Mood

1. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD. Population and Vital Statistics Report. Table 3. 2007 Downloaded on February 3, 2014 from http://unstats.un.org/UNSD/demographic/sconcerns/mortality/mort2.htm.

2. Genazzani AR, Pluchino N, Luisi S, Luisi M. Estrogen, cognition and female ageing. Hum Reprod Update. 2007 Mar-Apr;13(2):175–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Coelingh Bennink HJ. Are all estrogens the same? Maturitas. 2004 Apr 15;47(4):269–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Gleason CE, Carlsson CM, Johnson S, Atwood C, Asthana S. Clinical pharmacology and differential cognitive efficacy of estrogen preparations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005 Jun;1052:93–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Asthana S. Estrogen and cognition: a true relationship? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Feb;52(2):316–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

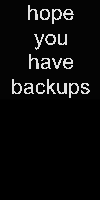

6. Rannevik G, Jeppsson S, Johnell O, Bjerre B, Laurell-Borulf Y, Svanberg L. A longitudinal study of the perimenopausal transition: altered profiles of steroid and pituitary hormones, SHBG and bone mineral density. Maturitas. 1995 Feb;21(2):103–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Irwin RW, Yao J, Hamilton RT, Cadenas E, Brinton RD, Nilsen J. Progesterone and estrogen regulate oxidative metabolism in brain mitochondria. Endocrinology. 2008 Jun;149(6):3167–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Brinton RD. Estrogen regulation of glucose metabolism and mitochondrial function: therapeutic implications for prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008 Oct-Nov;60(13–14):1504–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Brinton RD. The healthy cell bias of estrogen action: mitochondrial bioenergetics and neurological implications. Trends Neurosci. 2008 Oct;31(10):529–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Bailey ME, Wang AC, Hao J, Janssen WG, Hara Y, Dumitriu D, et al. Interactive effects of age and estrogen on cortical neurons: implications for cognitive aging. Neuroscience. 2011 Sep 15;191:148–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Hao J, Rapp PR, Janssen WG, Lou W, Lasley BL, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Interactive effects of age and estrogen on cognition and pyramidal neurons in monkey prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jul 3;104(27):11465–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hao J, Rapp PR, Janssen WG, Lou W, Lasley BL, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Interactive effects of age and estrogen on cognition and pyramidal neurons in monkey prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jul 3;104(27):11465–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Luine VN, Wallace ME, Frankfurt M. Age-related deficits in spatial memory and hippocampal spines in virgin, female Fischer 344 rats. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2011;2011:316386. Available from. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Luine V, Frankfurt M. Interactions between estradiol, BDNF and dendritic spines in promoting memory. Neuroscience. 2013 Jun 3;239:34–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Srivastava DP. Two-step wiring plasticity--a mechanism for estrogen-induced rewiring of cortical circuits. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012 Aug;131(1–2):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Wang AC, Hara Y, Janssen WG, Rapp PR, Morrison JH. Synaptic estrogen receptor-alpha levels in prefrontal cortex in female rhesus monkeys and their correlation with cognitive performance. J Neurosci. 2010 Sep 22;30(38):12770–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Neurosci. 2010 Sep 22;30(38):12770–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Green PS, Simpkins JW. Neuroprotective effects of estrogens: potential mechanisms of action. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000 Jul-Aug;18(4–5):347–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Solum DT, Handa RJ. Estrogen regulates the development of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA and protein in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002 Apr 1;22(7):2650–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Stirone C, Duckles SP, Krause DN, Procaccio V. Estrogen increases mitochondrial efficiency and reduces oxidative stress in cerebral blood vessels. Mol Pharmacol. 2005 Oct;68(4):959–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Ono H, Sasaki Y, Bamba E, Seki J, Giddings JC, Yamamoto J. Cerebral thrombosis and microcirculation of the rat during the oestrus cycle and after ovariectomy. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002 Jan-Feb;29(1–2):73–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Sunday L, Osuna C, Krause DN, Duckles SP. Age alters cerebrovascular inflammation and effects of estrogen. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007 May;292(5):h3333–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Age alters cerebrovascular inflammation and effects of estrogen. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007 May;292(5):h3333–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Johnson AB, Bake S, Lewis DK, Sohrabji F. Temporal expression of IL-1beta protein and mRNA in the brain after systemic LPS injection is affected by age and estrogen. J Neuroimmunol. 2006 May;174(1–2):82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Sribnick EA, Del Re AM, Ray SK, Woodward JJ, Banik NL. Estrogen attenuates glutamate-induced cell death by inhibiting Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Brain Res. 2009 Jun 18;1276:159–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Nilsen J, Diaz Brinton R. Mechanism of estrogen-mediated neuroprotection: regulation of mitochondrial calcium and Bcl-2 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Mar 4;100(5):2842–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Bagetta G, Chiappetta O, Amantea D, Iannone M, Rotiroti D, Costa A, et al. Estradiol reduces cytochrome c translocation and minimizes hippocampal damage caused by transient global ischemia in rat. Neurosci Lett. 2004 Sep 16;368(1):87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Estradiol reduces cytochrome c translocation and minimizes hippocampal damage caused by transient global ischemia in rat. Neurosci Lett. 2004 Sep 16;368(1):87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Prediger ME, Gamaro GD, Crema LM, Fontella FU, Dalmaz C. Estradiol protects against oxidative stress induced by chronic variate stress. Neurochem Res. 2004 Oct;29:1923–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Chiueh C, Lee S, Andoh T, Murphy D. Induction of antioxidative and antiapoptotic thioredoxin supports neuroprotective hypothesis of estrogen. Endocrine. 2003 Jun;21(1):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Dubal DB, Shughrue PJ, Wilson ME, Merchenthaler I, Wise PM. Estradiol modulates bcl-2 in cerebral ischemia: a potential role for estrogen receptors. J Neurosci. 1999 Aug 1;19(15):6385–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Garcia-Segura LM, Cardona-Gomez P, Naftolin F, Chowen JA. Estradiol upregulates Bcl-2 expression in adult brain neurons. Neuroreport. 1998 Mar 9;9(4):593–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Bake S, Ma L, Sohrabji F. Estrogen receptor-alpha overexpression suppresses 17beta-estradiol-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression and activation of survival kinases. Endocrinology. 2008 Aug;149(8):3881–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Nordell VL, Scarborough MM, Buchanan AK, Sohrabji F. Differential effects of estrogen in the injured forebrain of young adult and reproductive senescent animals. Neurobiol Aging. 2003 Sep;24(5):733–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Tinkler GP, Tobin JR, Voytko ML. Effects of two years of estrogen loss or replacement on nucleus basalis cholinergic neurons and cholinergic fibers to the dorsolateral prefrontal and inferior parietal cortex of monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2004 Feb 16;469(4):507–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Dumas J, Hancur-Bucci C, Naylor M, Sites C, Newhouse P. Estrogen treatment effects on anticholinergic-induced cognitive dysfunction in normal postmenopausal women. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006 Sep;31(9):2065–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006 Sep;31(9):2065–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Dumas JA, Kutz AM, Naylor MR, Johnson JV, Newhouse PA. Estradiol treatment altered anticholinergic-related brain activation during working memory in postmenopausal women. Neuroimage. 2012 Apr 2;60(2):1394–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Henderson JA, Bethea CL. Differential effects of ovarian steroids and raloxifene on serotonin 1A and 2C receptor protein expression in macaques. Endocrine. 2008 Jun;33(3):285–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Halbreich U, Kahn LS. Role of estrogen in the aetiology and treatment of mood disorders. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(10):797–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Epperson CN, Amin Z, Ruparel K, Gur R, Loughead J. Interactive effects of estrogen and serotonin on brain activation during working memory and affective processing in menopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012 Mar;37(3):372–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Wharton W, Gleason CE, Olson SR, Carlsson CM, Asthana S. Neurobiological Underpinnings of the Estrogen - Mood Relationship. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2012 Aug 1;8(3):247–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wharton W, Gleason CE, Olson SR, Carlsson CM, Asthana S. Neurobiological Underpinnings of the Estrogen - Mood Relationship. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2012 Aug 1;8(3):247–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Chakravorty SG, Halbreich U. The influence of estrogen on monoamine oxidase activity. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(2):229–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003 May 28;289(20):2651–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, Rapp SR, Thal L, Lane DS, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004 Jun 23;291(24):2947–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Henderson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. May 28;289(20):2663–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Henderson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. May 28;289(20):2663–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Shumaker SA, Brunner R, Manson JE, Sherwin BB, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004 Jun 23;291(24):2959–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Simpkins JW, Perez E, Wang X, Yang S, Wen Y, Singh M. The potential for estrogens in preventing Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2009 Jan;2(1):31–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Hogervorst E, Williams J, Budge M, Riedel W, Jolles J. The nature of the effect of female gonadal hormone replacement therapy on cognitive function in post-menopausal women: a meta-analysis. Neuroscience. 2000;101(3):485–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuroscience. 2000;101(3):485–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Grady D, Yaffe K, Kristof M, Lin F, Richards C, Barrett-Connor E. Effect of postmenopausal hormone therapy on cognitive function: the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Am J Med. 2002 Nov;113(7):543–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Maki PM. Critical window hypothesis of hormone therapy and cognition: a scientific update on clinical studies. Menopause. 2013 Jun;20(6):695–709. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Maki PM, Dennerstein L, Clark M, Guthrie J, LaMontagne P, Fornelli D, et al. Perimenopausal use of hormone therapy is associated with enhanced memory and hippocampal function later in life. Brain Res. 2011 Mar 16;1379:232–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. MacLennan AH, Henderson VW, Paine BJ, Mathias J, Ramsay EN, Ryan P, et al. Hormone therapy, timing of initiation, and cognition in women aged older than 60 years: the REMEMBER pilot study. Menopause. 2006 Jan-Feb;13(1):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2006 Jan-Feb;13(1):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Chaddock L, Kramer AF. A cross-sectional study of hormone treatment and hippocampal volume in postmenopausal women: evidence for a limited window of opportunity. Neuropsychology. 2010 Jan;24(1):68–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Kocoska-Maras L, Zethraeus N, Rådestad AF, Ellingsen T, von Schoultz B, Johannesson M, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of testosterone and estrogen on verbal fluency, verbal memory, and spatial ability in healthy postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2011 Jan;95(1):152–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Henderson VW, St John JA, Hodis HN, McCleary CA, Stanczyk FZ, Karim R, et al. Cognition, mood, and physiological concentrations of sex hormones in the early and late postmenopause. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Dec 10;110(50):20290–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Gleason CE, Dowling NM, Friedman E, Wharton W, Asthana S. Using predictors of hormone therapy use to model the healthy user bias: how does healthy user status influence cognitive effects of hormone therapy? Menopause. 2012 May 19;19(5):524–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Using predictors of hormone therapy use to model the healthy user bias: how does healthy user status influence cognitive effects of hormone therapy? Menopause. 2012 May 19;19(5):524–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Hogervorst E. Effects Of Gonadal Hormones On Cognitive Behavior In Elderly Men And Women. J Neuroendocrinol. 2013 Jul 29;(5):1182–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Wharton W, Gleason CE, Miller VM, Asthana S. Rationale and design of the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) and the KEEPS cognitive and affective sub study (KEEPS Cog) Brain Res. 2013 Jun 13;1514:12–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Hogervorst E, Yaffe K, Richards M, Huppert FA. Hormone replacement therapy to maintain cognitive function in women with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan 21;(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Weissberger AJ, Ho KK, Lazarus L. Contrasting effects of oral and transdermal routes of estrogen replacement therapy on 24-hour growth hormone (GH) secretion, insulin-like growth factor I, and GH-binding protein in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991 Feb;72(2):374–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991 Feb;72(2):374–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Foy MR, Baudry M, Wang J, Finch CE, et al. Progesterone receptors: form and function in brain. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008 May;29(2):313–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Walf AA, Paris JJ, Rhodes ME, Simpkins JW, Frye CA. Divergent mechanisms for trophic actions of estrogens in the brain and peripheral tissues. Brain Res. 2011 Mar 16;1379:119–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. de Lignières B. Oral micronized progesterone. Clin Ther. 1999;21(1):41–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Buckwalter JG, Crooks VC, Robins SB, Petitti DB. Advanced Age. 2004:182–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Zandi PP, Carlson MC, Plassman BL, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Mayer LS, Steffens DC, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and incidence of Alzheimer disease in older women: the Cache County Study. JAMA. 2002 Nov 6;288(17):2123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Shao H, Breitner JCS, Whitmer RA, Wang J, Hayden K, Wengreen H, et al. Hormone therapy and Alzheimer disease dementia: new findings from the Cache County Study. Neurology. 2012 Oct 30;79(18):1846–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shao H, Breitner JCS, Whitmer RA, Wang J, Hayden K, Wengreen H, et al. Hormone therapy and Alzheimer disease dementia: new findings from the Cache County Study. Neurology. 2012 Oct 30;79(18):1846–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Albertazzi P, Natale V, Barbolini C, Teglio L, Di Micco R. The effect of tibolone versus continuous combined norethisterone acetate and oestradiol on memory, libido and mood of postmenopausal women: a pilot study. Maturitas. 2000 Oct 31;36(3):223–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Shaywitz SE, Naftolin F, Zelterman D, Marchione KE, Holahan JM, Palter SF, et al. Better oral reading and short-term memory in midlife, postmenopausal women taking estrogen. Menopause. 2003 Sep-Oct;10(5):420–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Joffe H, Hall JE, Gruber S, Sarmiento Ia, Cohen LS, Yurgelun-Todd D, et al. Estrogen therapy selectively enhances prefrontal cognitive processes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with functional magnetic resonance imaging in perimenopausal and recently postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2006 May-Jun;13(3):411–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Menopause. 2006 May-Jun;13(3):411–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Alhola P, Tuomisto H, Saarinen R, Portin R, Kalleinen N, Polo-Kantola P. Estrogen + progestin therapy and cognition: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010 Aug;36(4):796–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Sherwin BB, Grigorova M. Differential effects of estrogen and micronized progesterone or medroxyprogesterone acetate on cognition in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2011 Aug;96(2):399–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Möller MC, Bartfai AB, Rådestad AF. Effects of testosterone and estrogen replacement on memory function. Menopause. 2010 Sep-Oct;17(5):983–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Asthana S, Baker LD, Craft S, Stanczyk FZ, Veith RC, Raskind MA, et al. High-dose estradiol improves cognition for women with AD: results of a randomized study. Neurology. 2001 Aug 28;57(4):605–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Wharton W, Baker LD, Gleason CE, Dowling M, Barnet JH, Johnson S, et al. Short-term hormone therapy with transdermal estradiol improves cognition for postmenopausal women with Alzheimer’s disease: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26(3):495–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Short-term hormone therapy with transdermal estradiol improves cognition for postmenopausal women with Alzheimer’s disease: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26(3):495–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Schiff R, Bulpitt CJ, Wesnes KA, Rajkumar C. Short-term transdermal estradiol therapy, cognition and depressive symptoms in healthy older women. A randomised placebo controlled pilot cross-over study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005 May;30(4):309–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Almeida OP, Lautenschlager NT, Vasikaran S, Leedman P, Gelavis A, Flicker L. A 20-week randomized controlled trial of estradiol replacement therapy for women aged 70 years and older: effect on mood, cognition and quality of life. Neurobiol Aging. 2006 Jan;27(1):141–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Wolf OT, Heinrich AB, Hanstein B, Kirschbaum C. Estradiol or estradiol/progesterone treatment in older women: no strong effects on cognition. Neurolbiol Aging. 2005 Jul;26:1029–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2005 Jul;26:1029–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Maki PM, Gast MJ, Vieweg aJ, Burriss SW, Yaffe K. Hormone therapy in menopausal women with cognitive complaints: a randomized, double-blind trial. Neurology. 2007 Sep 25;69(13):1322–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Whooley MA, Grady D, Cauley JA. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and depressive symptoms in older women. J Gen Intern Med. 2000 Aug;15(8):535–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Toffol E, Heikinheimo O, Partonen T. Associations between psychological well-being, mental health, and hormone therapy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: results of two population-based studies. Menopause. 2013 Jun;20:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Amore M, Di Donato P, Berti A, Palareti A, Chirico C, Papalini A, et al. Sexual and psychological symptoms in the climacteric years. Maturitas. 2007 Mar 20;56(3):303–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Kornstein SG, Toups M, Rush aJ, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, Luther J, et al. Do menopausal status and use of hormone therapy affect antidepressant treatment response? Findings from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013 Feb;22(2):121–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Do menopausal status and use of hormone therapy affect antidepressant treatment response? Findings from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013 Feb;22(2):121–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Stephens C, Bristow V, Pachana NA. HRT and everyday memory at menopause_: a comparison of two samples of mid-aged women. 2006;43(1):37–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Schmidt PJ, Nieman L, Danaceau MA, Tobin MB, Roca CA, Murphy JH, et al. Estrogen replacement in perimenopause-related depression: a preliminary report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Aug;183(2):414–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, Cohen LS. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001 Jun;58(6):529–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Onalan G, Onalan R, Selam B, Akar M, Gunenc Z, Topcuoglu A. Mood scores in relation to hormone replacement therapies during menopause: a prospective randomized trial. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005 Nov;207(3):223–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mood scores in relation to hormone replacement therapies during menopause: a prospective randomized trial. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005 Nov;207(3):223–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Karsidag C, Karsidag A, Buyukbayrak E, kars B, Pirimoglu M, Unal O, Turan C. Comparison of effects of two different hormone therapies on mood and symptomatic postmenopausal women. Arch Neuropsychiatry. 2012;49:39–43. [Google Scholar]

HRT linked to depression – here's what the evidence actually says

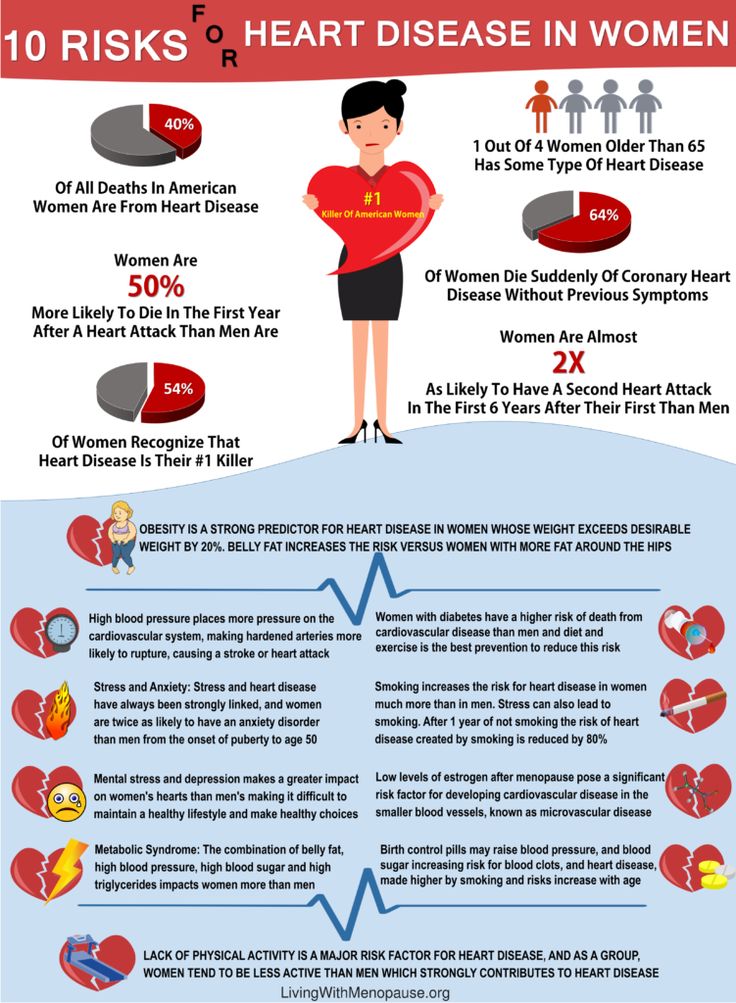

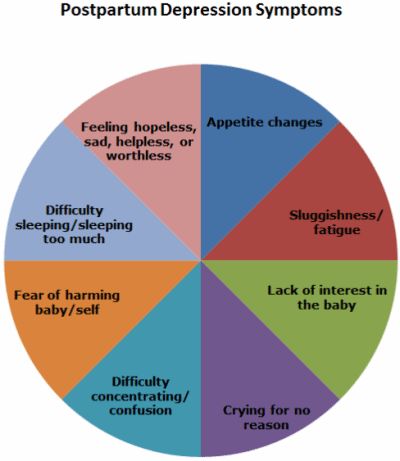

A growing number of women are turning to hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to alleviate distressing symptoms of the menopause – including hot flushes, bladder weakness, vaginal dryness, joint pain, brain fog, sleep disturbances, anxiety and depression. For many women, HRT can help manage symptoms and minimise disruptions to daily life.

The past five years alone has seen monthly prescriptions of HRT double in England. Part of this increase is thanks to continued research on the wide-reaching benefits of HRT and awareness campaigns by menopause specialists and celebrities such as Davina McCall.

As research into HRT continues, it’s understandable that women may be concerned when they see studies or headlines showing potential harms from HRT use. Take a recent Danish study which showed a link between HRT use and depression. Many media outlets reporting on these findings initially suggested that HRT “makes women depressed”. But while the study may have identified an association between HRT and depression, it did not actually show that taking HRT made women depressed.

Understanding the results

This was a large study, examining 825,238 women who were 45 years old at the outset and following them for about ten years. The data on the type of HRT the women took and whether they were later diagnosed with depression was available from Danish National registers. The main aim of the study was to examine if there was an increased risk of being diagnosed with depression after having started HRT.

The results show that among women who were given HRT locally (as a vaginal cream, pessary or implant in the womb), there was no increased risk of being diagnosed with depression. Indeed, the researchers found that for women aged 54-56, local HRT was associated with a decreased risk of being diagnosed with depression.

Indeed, the researchers found that for women aged 54-56, local HRT was associated with a decreased risk of being diagnosed with depression.

However, women given HRT systemically (either via pills or through the skin using a patch) were more likely to be diagnosed with depression, especially between the ages of 48 and 50, compared with women who were not on HRT. Being diagnosed with depression was also more likely in the year after starting treatment, but then declined over time.

Are we to conclude that HRT increases the risk of depression? In short, no – mainly because this was an observational study and the researchers had no data on the women’s symptoms or reasons for starting on HRT. This means we cannot rule out whether some of the women may have had undiagnosed depression before starting on HRT.

Women may also be more vulnerable to depression in the years before and just after starting the menopause. This could potentially explain why women were more likely to be diagnosed with depression not long after beginning HRT.

And it cannot be ruled out that the women who started using HRT pills or patches did so because of more severe menopause symptoms. This could explain why this group was more likely to receive a subsequent depression diagnosis.

Different forms of HRT may be prescribed depending on the symptoms women are experiencing. wutzkohphoto/ ShutterstockSimilarly, local HRT is usually only given for genito-urinary symptoms such as vaginal dryness – and not for women experiencing other menopausal symptoms such as depression. This could explain why women in the local HRT group were less likely overall to be diagnosed with depression.

In line with current evidence and recommendations, HRT should still be offered to otherwise healthy women during the perimenopause or early postmenopause with moderate to severe symptoms, as the benefits outweigh the risks in this age group. Cognitive behavioural therapy is also recommended for managing depression during the menopause. Women with more severe depression should be referred for a formal mental health assessment.

Women with more severe depression should be referred for a formal mental health assessment.

Reporting the results

Careful reporting of scientific studies is important, as inaccurate or misleading coverage and headlines can lead to years of fear and mistrust. For example, use of HRT declined by as much as 80% in 2002 when a study linked HRT with breast cancer and heart disease. Although this study is now considered flawed – and other studies have since shown that HRT is actually beneficial for women’s cardiometabolic health – the fear created by media coverage of it left a legacy of anxiety and confusion that still persists surrounding HRT today.

Media outlets who erroneously suggested that HRT causes depression in their initial coverage of the study may have inadvertently put some women off from using HRT, which means they may miss out on its benefits.

This is why it’s so important to point out that the study has not shown HRT causes depression. In fact, some studies have shown that HRT might improve and even prevent women’s depression symptoms during menopause. Future, larger studies are needed to confirm these potential benefits of HRT for depression.

Future, larger studies are needed to confirm these potential benefits of HRT for depression.

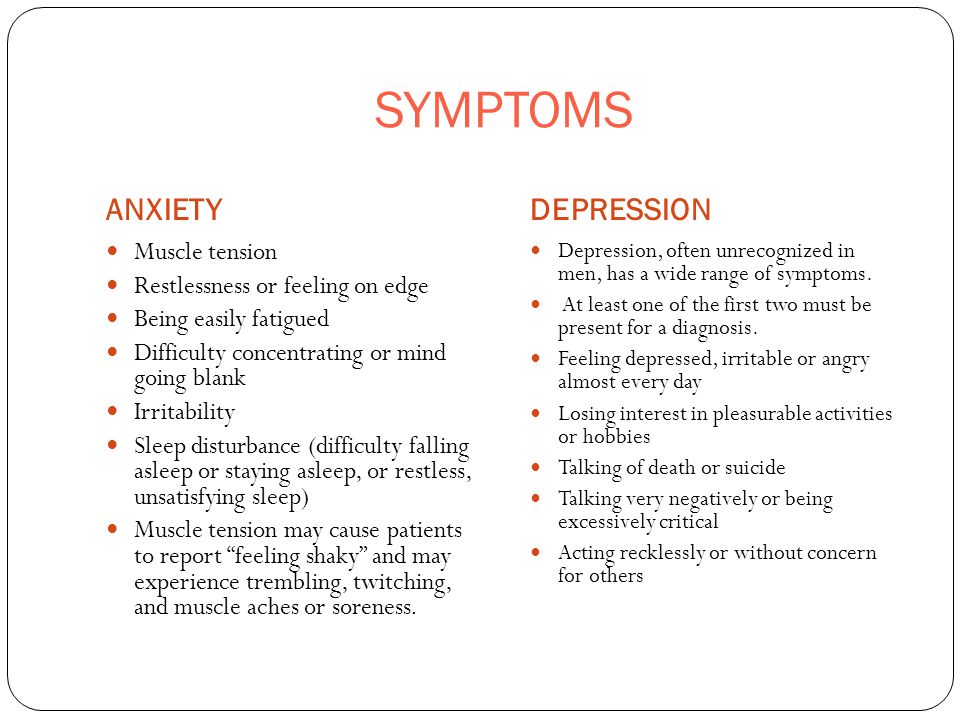

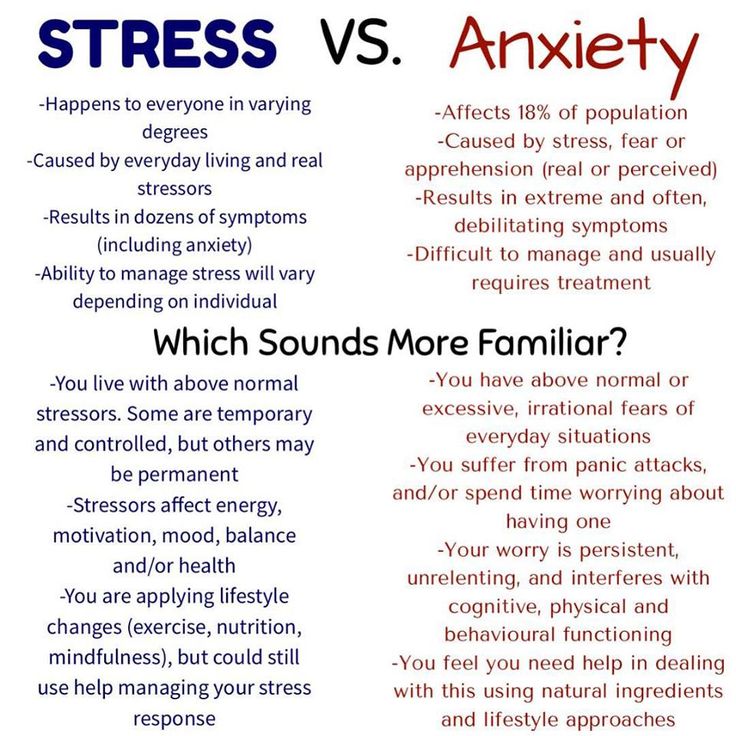

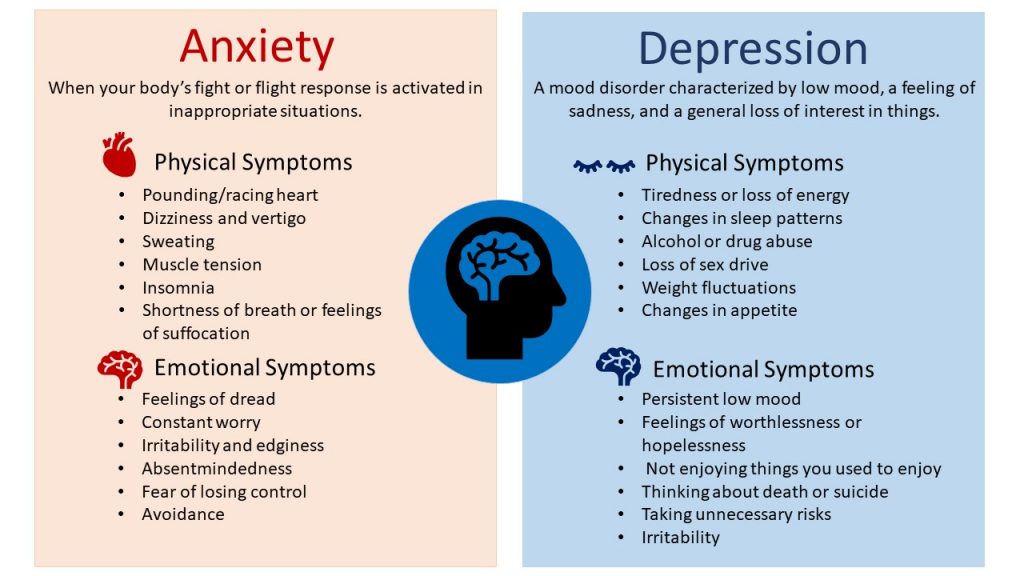

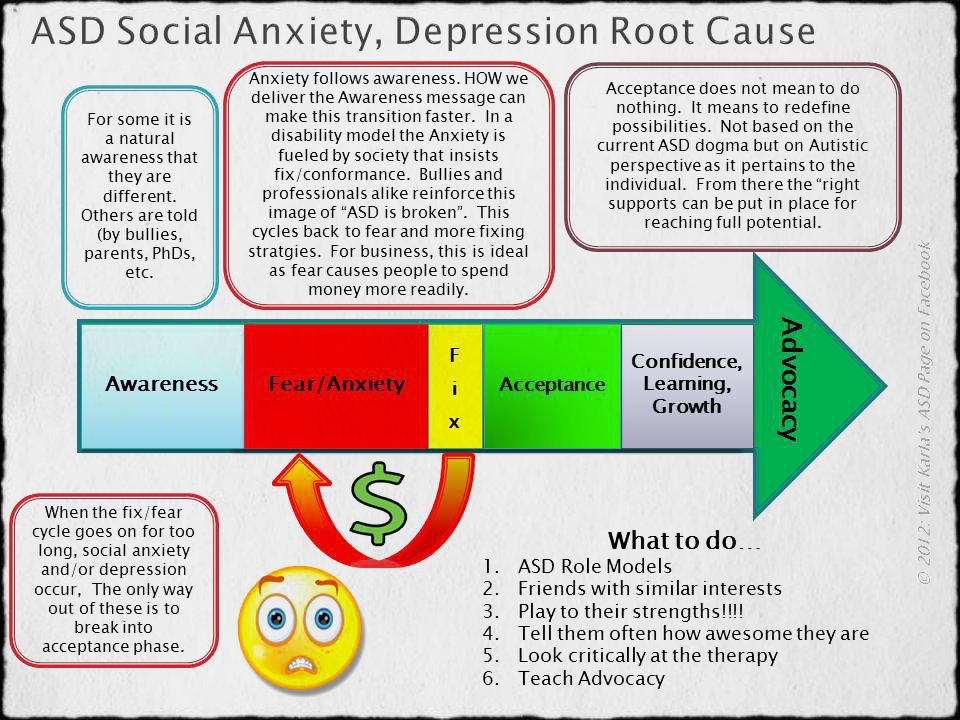

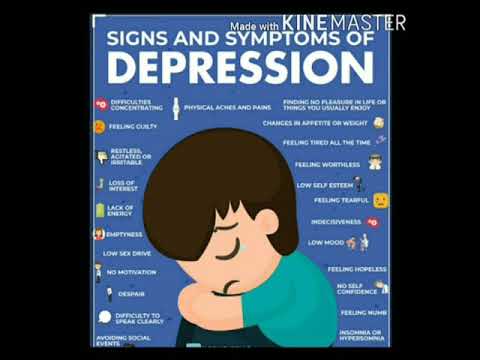

Main differences between depression and anxiety

Publication date

June 9, 2022

PSYCHOLOGY

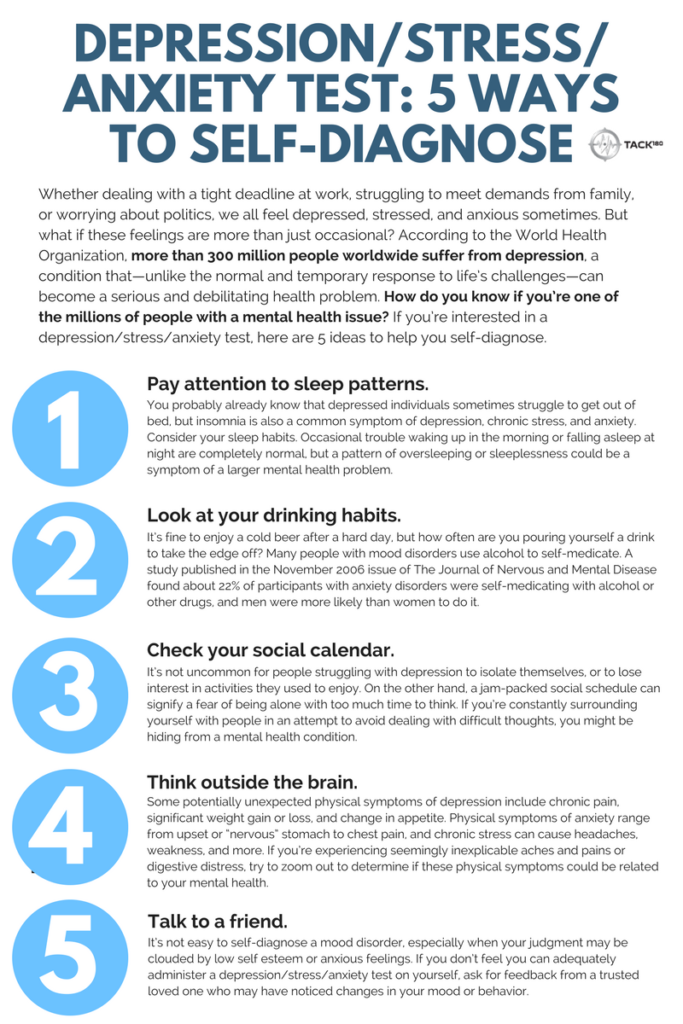

There are many things to worry about in our lives. Some are worried about problems at work, others are worried as a result of a protracted family conflict. The difference is that someone experiences just an emotion that changes together with external circumstances, and someone develops a psychopathological syndrome. In this article, we will look at how depression and anxiety disorder differ from each other, and what physical signs they have. nine0003

Mental differences between anxiety and depression

Not all people are able to distinguish between these states. Each of them has its own characteristics.

Alarm

Anxiety is the body's response to stress. There are two types of anxiety:

There are two types of anxiety:

- Adaptive. Healthy people may experience discomfort in conditions that seem dangerous to the brain. However, adaptive anxiety passes quickly and does not have a negative impact on life. nine0023

- Pathological. With regard to this type of anxiety, it has a pronounced all-consuming feeling, accompanied by a feeling of helplessness and intense threat. This reaction can occur without any reason. Pathological anxiety can be chronic, paroxysmal and post-stress.

Persistent, or chronic, anxiety is the most common and has a negative effect on a person's emotional health and life. nine0003

With an anxiety disorder, a person experiences constant fears that something is about to happen in the future. He constantly has thoughts that something will go wrong. He tries to avoid things that cause anxiety.

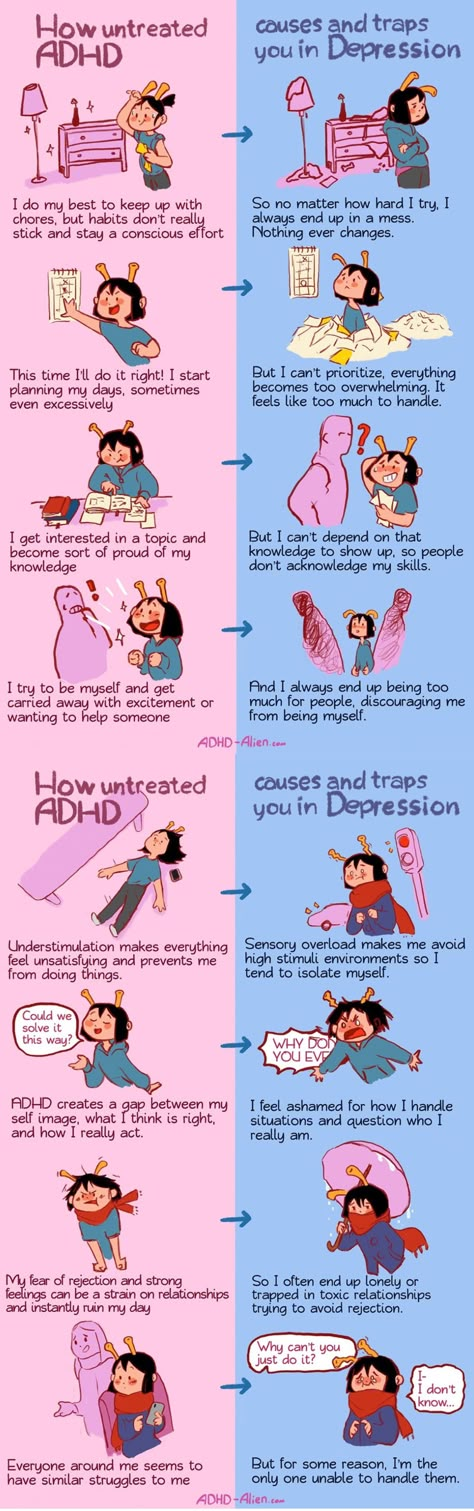

Depression

A person can be depressed for weeks or months. The presence of this disease may even affect how quickly he can recover from illness. Most often, depression occurs as a result of a combination of several traumatic factors. Often it is provoked by events such as the death of a loved one, moving, a serious illness, childbirth. nine0003

Most often, depression occurs as a result of a combination of several traumatic factors. Often it is provoked by events such as the death of a loved one, moving, a serious illness, childbirth. nine0003

In a depressed state, a person feels sadness, and it seems to him that the future is hopeless. He does not believe that something good is waiting for him, and if he feels anxiety, then very little. There may be suicidal thoughts.

Physical state differences

Both conditions often have physiological manifestations. In the case of an anxiety disorder, they appear after intense anxiety. In depression, the physical symptoms are almost constant. nine0003

The most typical manifestations of anxiety:

- Tension in the body and muscles.

- Tachycardia.

- Excessive sweating.

- Chill.

- Dizziness.

- Nausea.

- Tremor.

- Pain in the abdomen, head and other parts of the body.

- Difficulty breathing.

- The degree of manifestation of the disorder largely depends on the stage of the disease and its neglect. To prevent depression from appearing against the background of a psychopathological state, treatment of anxiety should be started at the very first of its symptoms. nine0023

- The main physical manifestations of depression are:

- Apathy.

- Constant fatigue.

- Sleep and appetite disturbance.

- Lack of energy.

- Lethargy.

Often these two diseases are also confused for the reason that depression can arise as a result of experienced anxiety. A person can feel completely empty and hopeless even if the alarming situation has been eliminated. nine0003

Helping people with depression in Minsk includes sessions with a specialist and drug therapy, which helps to understand yourself and your thoughts. Conversations with a psychotherapist allow a person to develop the skills of correct behavior and reaction to stressful situations, as well as form the correct attitude to what is happening.

Common mistakes in treating depression and anxiety

Since the effectiveness of treatment largely depends on the patient, it is necessary to listen to all the recommendations given by the doctor. However, many people make mistakes that can negatively affect recovery: nine0003

- Delay with the start of therapy.

- Self-treatment.

- Self-correction of the treatment prescribed by the doctor.

- Alcohol use during therapy.

Starting early and following the advice of a psychotherapist helps to mitigate the manifestations of the disease, reduce the duration of treatment and the risk of recurrence of depression and anxiety.

See also:

Neurotic personality disorder

Why do we need a child psychologist?

Prevention of computer addiction

How do you know if you have irritable bowel syndrome?

How does acupuncture feel?

Neurasthenia: symptoms, signs, causes and diagnosis

Signs of a toxic relationship0006

10 signs that you have anxiety

How does reflexology help?

Symptoms of neurosis in women

How to cope with the death of a loved one?

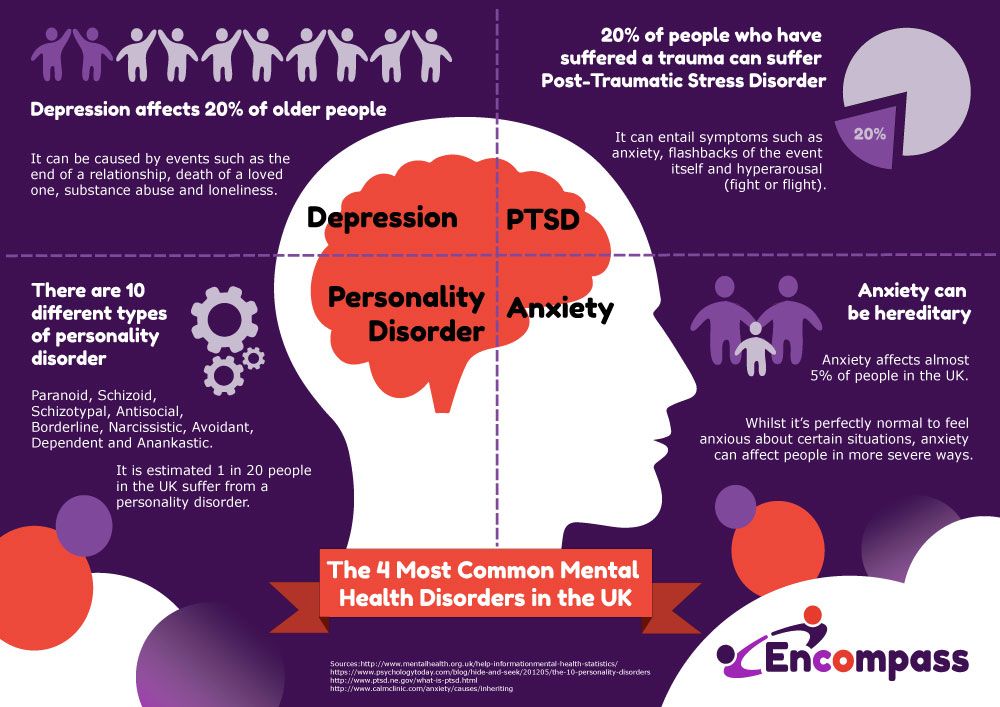

What do we know about anxiety and depression?

Evgeniy Gennadievich Ilchenko, psychotherapist of the Department for the Treatment of Borderline Mental Disorders and Psychotherapy of the National Research Center for Psychiatry and Neurology. V.M. Bekhterev. nine0152 Anxiety, depression are conditions that are characteristic of violations of the state of the emotional sphere. Today, about 110 million people in the world suffer from depression. According to the World Health Organization, one in five women and one in fifteen men suffer from depression in major cities around the world. It is believed that by 2020 depression will take one of the first places among all diseases. Approximately 70% of depressed patients show suicidal tendencies, and depressed patients older than 75 have the highest rate of suicide. nine0003

V.M. Bekhterev. nine0152 Anxiety, depression are conditions that are characteristic of violations of the state of the emotional sphere. Today, about 110 million people in the world suffer from depression. According to the World Health Organization, one in five women and one in fifteen men suffer from depression in major cities around the world. It is believed that by 2020 depression will take one of the first places among all diseases. Approximately 70% of depressed patients show suicidal tendencies, and depressed patients older than 75 have the highest rate of suicide. nine0003

I am suffering, I am afraid…

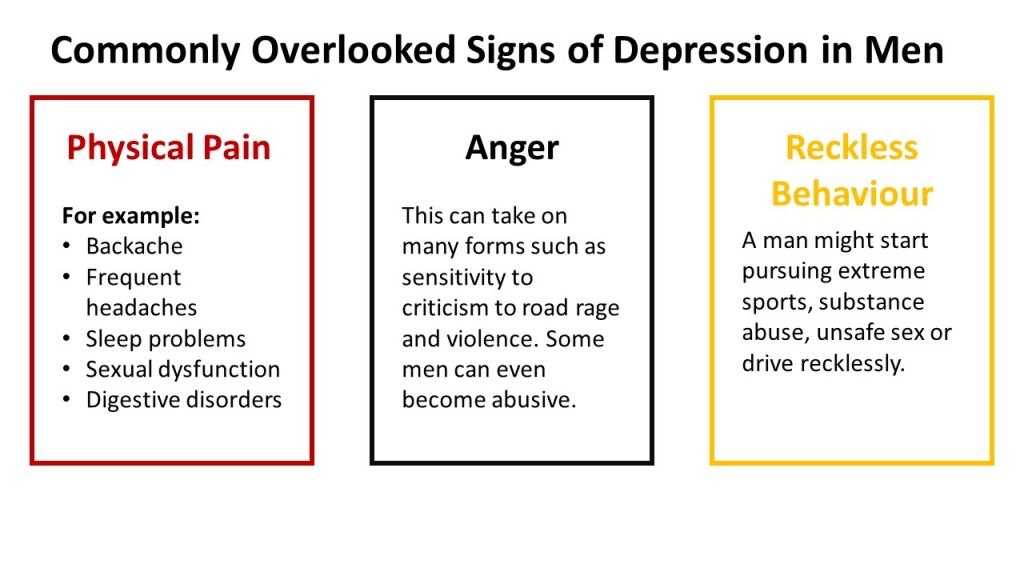

What is depression? Depression is a disease that can throw a person out of emotional balance for a long time and significantly impair the quality of his life. It can be difficult for you to concentrate, nothing is interesting, nothing pleases, doubts and fears are constantly overcome. Depression usually comes after a psychological trauma or negative event. Often it develops as if for no apparent reason. It can be caused by constant stress, accumulating fatigue, fears. Depression is more than just low mood. In this case, the work of the whole organism changes, as a person suffers from insomnia or early awakenings, he loses his appetite or begins to seize his anxiety, which leads to obesity and the development of metabolic syndrome, there is a hormonal imbalance. A person changes his attitude towards others and himself. nine0003

Often it develops as if for no apparent reason. It can be caused by constant stress, accumulating fatigue, fears. Depression is more than just low mood. In this case, the work of the whole organism changes, as a person suffers from insomnia or early awakenings, he loses his appetite or begins to seize his anxiety, which leads to obesity and the development of metabolic syndrome, there is a hormonal imbalance. A person changes his attitude towards others and himself. nine0003

Sadness, apathy, anxiety…

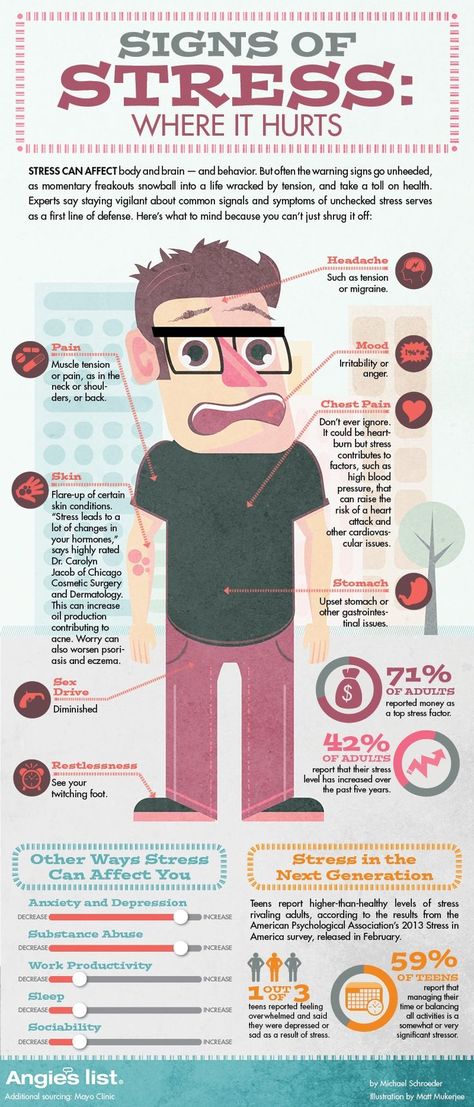

How does depression manifest itself? The first symptoms include weakness, fatigue, unwillingness to do anything, strain once again, contact and communicate with people, go to work. Later, bodily symptoms may join these complaints - palpitations, sweating, trembling in the body, hot or cold flashes.

Three areas are involved in depression - emotional, mental and physical. At the emotional level, depression, melancholy, apathy, and anxiety are observed. On the mental level - thoughts about one's guilt, self-accusations, a negative vision of the future, a feeling of hopelessness, that "no one will help me." On the physical level - chronic pain, muscle tension, constipation, dizziness, heaviness in the head. And all these symptoms can constantly change: “Today my head hurts, and yesterday my joints hurt, the day before yesterday my heart hurt.” nine0003

On the mental level - thoughts about one's guilt, self-accusations, a negative vision of the future, a feeling of hopelessness, that "no one will help me." On the physical level - chronic pain, muscle tension, constipation, dizziness, heaviness in the head. And all these symptoms can constantly change: “Today my head hurts, and yesterday my joints hurt, the day before yesterday my heart hurt.” nine0003

Maybe it's psychosomatics?

It is worth noting that there are different types of depression. According to the classification, depressions are diverse: major, minor, neurotic, autumnal, endogenous, psychogenic, reactive, etc. There is depression associated with the reproductive function of a woman, this is prenatal and postnatal. There is age-related depression associated with the physiological restructuring of the body, there is an obvious one that occurs with a sharply reduced mood, melancholy, and depression. There is a masked depression that hides under the guise of another disease. For example, chronic pain syndrome - pain in different parts of the body. There is depression, which is masked by gastrointestinal symptoms - diarrhea, constipation, stomach pain. Patients go to doctors for a long time and unsuccessfully, are treated by different specialists. But there is no improvement. At this stage, it is important to recognize psychosomatic disorders. It is worth looking, but what gives a person a disease? How is she good for him? It is quite possible that in this way a person attracts attention to himself, seeks location, manipulates loved ones and relatives. nine0003

For example, chronic pain syndrome - pain in different parts of the body. There is depression, which is masked by gastrointestinal symptoms - diarrhea, constipation, stomach pain. Patients go to doctors for a long time and unsuccessfully, are treated by different specialists. But there is no improvement. At this stage, it is important to recognize psychosomatic disorders. It is worth looking, but what gives a person a disease? How is she good for him? It is quite possible that in this way a person attracts attention to himself, seeks location, manipulates loved ones and relatives. nine0003

How can I help?

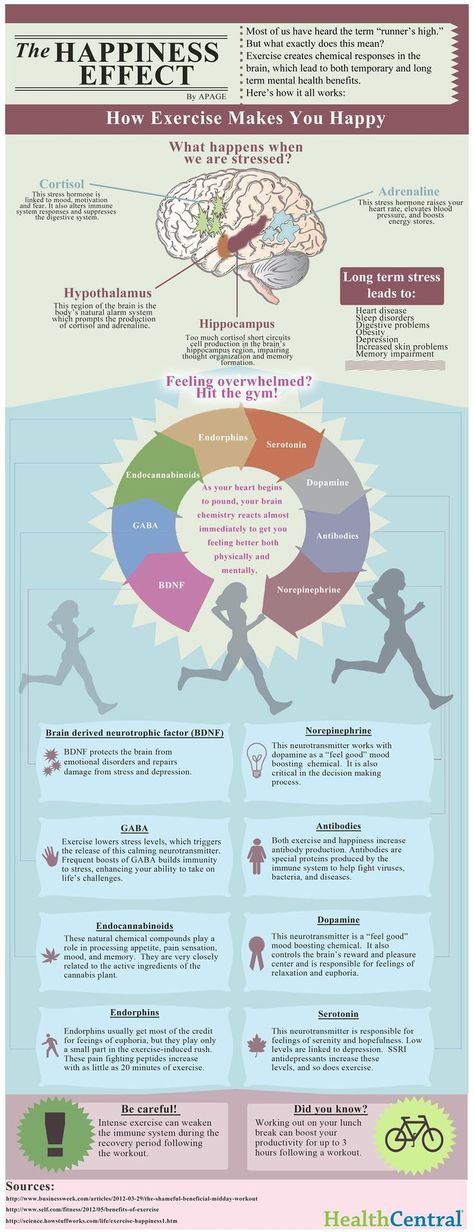

Sometimes patients with depression try to alleviate their mental state through physical pain, inflicting injuries and injuries on themselves. This is definitely not an option. How can others help such patients? First of all, do not ignore or forbid complaining, do not try to cheer up the patient, do not appeal to conscience and faith, do not demand the adoption of any important decisions, but simply be there and listen patiently. As for direct treatment, there is no “magic” remedy for depression. Various methods are used here: psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, electroconvulsive therapy, physiotherapy, aroma and color therapy, physical activity. If we talk about the prevention of depression, then this is a healthy lifestyle and a positive attitude, communication with nature. nine0003

As for direct treatment, there is no “magic” remedy for depression. Various methods are used here: psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, electroconvulsive therapy, physiotherapy, aroma and color therapy, physical activity. If we talk about the prevention of depression, then this is a healthy lifestyle and a positive attitude, communication with nature. nine0003

Experiences about the future

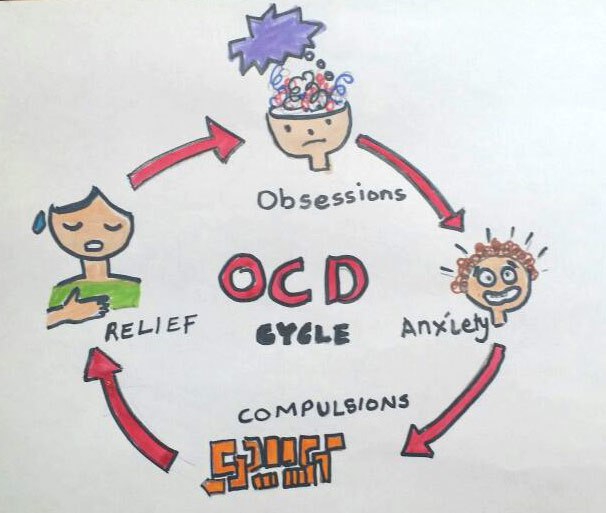

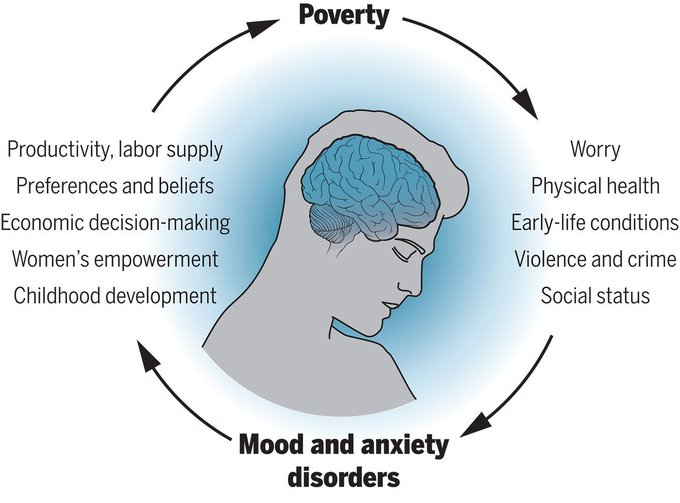

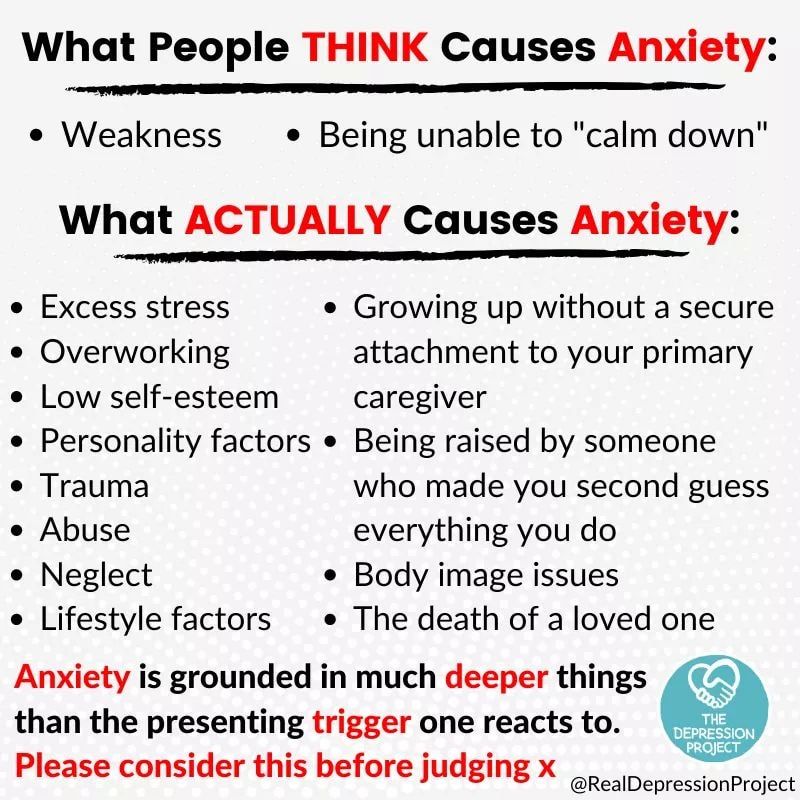

Depression is a negative experience of past life events that we cannot change, while anxiety is an experience for the future, this is a vague, unpleasant emotional state characterized by the expectation of an unfavorable development of events, the presence of bad forebodings, tension and anxiety. It is directed to the future, it is the expectation of something indefinite. The state of anxiety is pointless, but anxiety is a personality trait of a person prone to experiencing anxiety, and constantly experiencing it. Most often, a person's anxiety is associated with the expectation of the social consequences of his success or failure. nine0152 Risk factors for the development of anxiety include childhood trauma, stress, personality traits, genetic predisposition, alcohol and psychoactive substances. Anxiety can be normal or excessive. In pathological cases, anxiety becomes constant and harmful, appearing not only in stressful situations, but also for no apparent reason, and then anxiety not only does not help a person, but begins to interfere with his daily activities.

nine0152 Risk factors for the development of anxiety include childhood trauma, stress, personality traits, genetic predisposition, alcohol and psychoactive substances. Anxiety can be normal or excessive. In pathological cases, anxiety becomes constant and harmful, appearing not only in stressful situations, but also for no apparent reason, and then anxiety not only does not help a person, but begins to interfere with his daily activities.

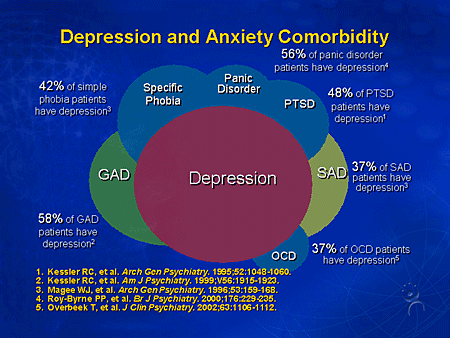

Panic attacks

The largest category of anxiety disorders are phobias, with about a hundred variants. Anxiety disorders include post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety, panic attacks, and separation anxiety. Speaking of anxiety, it is worth mentioning panic attacks separately. How do they appear? Unexpected internal tension, pointless fear, timidity, stiffness, feeling of danger, unreality of what is happening, "lump in the throat", chills, sweating, heart palpitations, suffocation, nausea, diarrhea, dizziness, goosebumps, restlessness.