Stress changes how people make decisions

Stress and Decision Making: Effects on Valuation, Learning, and Risk-taking

1. Glimcher PW, Rustichini A. Neuroeconomics: The consilience of brain and decision. Science. 2004;306(5695):447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Sandi C, Pinelo-Nava MT. Stress and memory: behavioral effects and neurobiological mechanisms. Neural Plast. 2007;78970:1–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Selye H. A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. Nature. 1936;138:32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):397–409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Cannon WB. Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear, and rage: An account of recent researches into the function of emotional excitement. New York: D. Appleton and Company; 1915. [Google Scholar]

6. Pabst S, Brand M, Wolf OT. Stress and decision making: a few minutes make all the difference. Behav Brain Res. 2013;250:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Dias-Ferreira E, Sousa JC, Melo I, Morgado P, Mesquita AR, Cerqueira JJ, et al. Chronic stress causes frontostriatal reorganization and affects decision-making. Science. 2009;325(5940):621–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. A study demonstrating chronically stressed rats shift from goal-directed to habit-based responses, associated with atrophy and hypertrophy (respectively) of associated brain regions.

8. McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):873–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):434–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

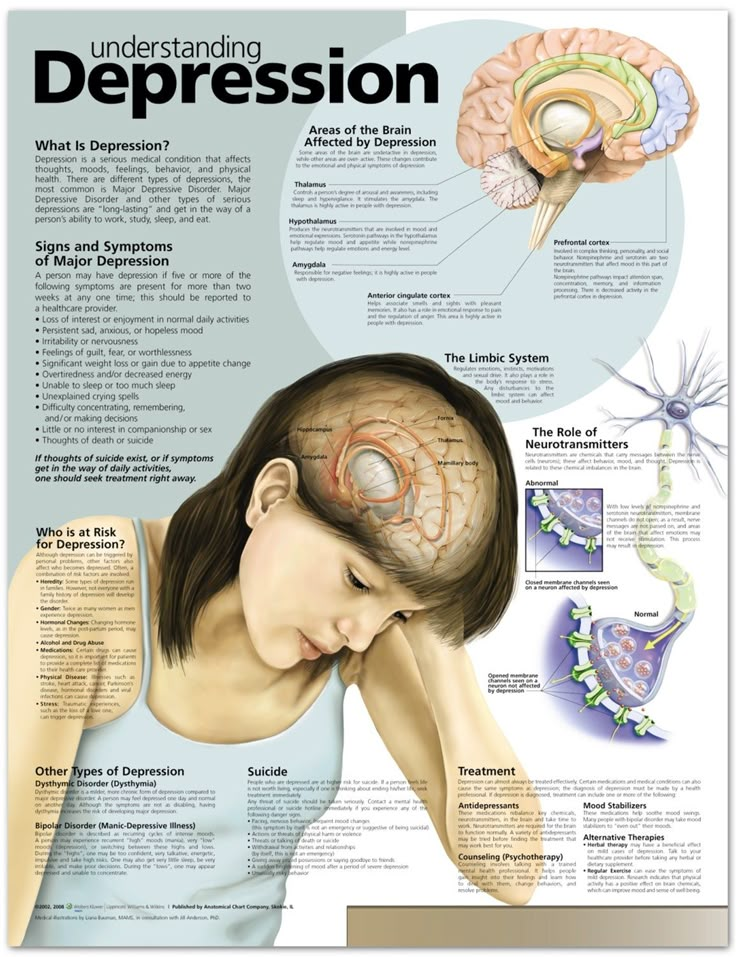

10. Tottenham N, Galvan A. Stress and the adolescent brain: Amygdala-prefrontal cortex circuitry and ventral striatum as developmental targets. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;70:217–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. A review of literature on stress exposure in early childhood through adolescence, proposing neurobiological changes in amygdala, PFC, and ventral striatum promote vulnerability to environmental stress and some mental illnesses later in life.

2016;70:217–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. A review of literature on stress exposure in early childhood through adolescence, proposing neurobiological changes in amygdala, PFC, and ventral striatum promote vulnerability to environmental stress and some mental illnesses later in life.

11. Groeneweg FL, Karst H, de Kloet ER, Joels M. Rapid non-genomic effects of corticosteroids and their role in the central stress response. J Endocrinol. 2011;209(2):153–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Rimmele U, Besedovsky L, Lange T, Born J. Blocking mineralocorticoid receptors impairs, blocking glucocorticoid receptors enhances memory retrieval in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(5):884–894. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Joels M, Karst H, DeRijk R, de Kloet ER. The coming out of the brain mineralocorticoid receptor. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Neurocircuitry of stress: central control of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20(2):78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Trends Neurosci. 1997;20(2):78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):355–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. A meta-analysis of acute stressors in lab-based studies, indicating that uncontrollability or social-evaluation evoke both greater and longer-lasting HPA reactivity.

16. Rangel A, Camerer C, Montague PR. A framework for studying the neurobiology of value-based decision making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(7):545–556. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Pessiglione M, Delgado MR. The good, the bad and the brain: Neural correlates of appetitive and aversive values underlying decision making. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2015;5:78–84. [Google Scholar]

18. Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol Behav. 2007;91(4):449–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Goudriaan AE, Oosterlaan J, de Beurs E, Van den Brink W. Pathological gambling: a comprehensive review of biobehavioral findings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28(2):123–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pathological gambling: a comprehensive review of biobehavioral findings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28(2):123–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Pizzagalli DA. Depression, stress, and anhedonia: toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:393–423. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Corral-Frias NS, Nikolova YS, Michalski LJ, Baranger DAA, Hariri AR, Bogdan R. Stress-related anhedonia is associated with ventral striatum reactivity to reward and transdiagnostic psychiatric symptomatology. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(12):2605–2617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Berghorst LH, Bogdan R, Frank MJ, Pizzagalli DA. Acute stress selectively reduces reward sensitivity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Bogdan R, Pizzagalli DA. Acute stress reduces reward responsiveness: implications for depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(10):1147–1154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Born JM, Lemmens SG, Rutters F, Nieuwenhuizen AG, Formisano E, Goebel R, et al. Acute stress and food-related reward activation in the brain during food choice during eating in the absence of hunger. Int J Obes. 2009;34(1):172–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Born JM, Lemmens SG, Rutters F, Nieuwenhuizen AG, Formisano E, Goebel R, et al. Acute stress and food-related reward activation in the brain during food choice during eating in the absence of hunger. Int J Obes. 2009;34(1):172–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Ossewaarde L, Qin S, Van Marle HJ, van Wingen GA, Fernandez G, Hermans EJ. Stress-induced reduction in reward-related prefrontal cortex function. Neuroimage. 2011;55(1):345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Porcelli AJ, Lewis AH, Delgado MR. Acute stress influences neural circuits of reward processing. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Kumar P, Berghorst LH, Nickerson LD, Dutra SJ, Goer FK, Greve DN, et al. Differential effects of acute stress on anticipatory and consummatory phases of reward processing. Neuroscience. 2014;266:1–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. An fMRI study examining acute stress effects on reward valuation at anticipation and receipt, demonstrating increased striatal and amygdala BOLD at anticipation but decreased striatal BOLD at receipt.

28. Hanson JL, Albert D, Iselin AMR, Carre JM, Dodge KA, Hariri AR. Cumulative stress in childhood is associated with blunted reward-related brain activity in adulthood. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2016;11(3):405–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Lighthall NR, Gorlick MA, Schoeke A, Frank MJ, Mather M. Stress modulates reinforcement learning in younger and older adults. Psychol Aging. 2013;28(1):35–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Petzold A, Plessow F, Goschke T, Kirschbaum C. Stress reduces use of negative feedback in a feedback-based learning task. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124(2):248–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Mather M, Lighthall NR. Risk and Reward Are Processed Differently in Decisions Made Under Stress. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2012;21(1):36–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Abercrombie ED, Keefe KA, DiFrischia DS, Zigmond MJ. Differential effect of stress on in vivo dopamine release in striatum, nucleus accumbens, and medial frontal cortex. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1989;52(5):1655–1658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Journal of Neurochemistry. 1989;52(5):1655–1658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Rouge-Pont F, Deroche V, Le Moal M, Piazza PV. Individual differences in stress-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens are influenced by corticosterone. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10(12):3903–3907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Scott DJ, Heitzeg MM, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK. Variations in the human pain stress experience mediated by ventral and dorsal basal ganglia dopamine activity. J Neurosci. 2006;26(42):10789–10795. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Pruessner JC, Champagne F, Meaney MJ, Dagher A. Dopamine release in response to a psychological stress in humans and its relationship to early life maternal care: a positron emission tomography study using [11C]raclopride. J Neurosci. 2004;24(11):2825–2831. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Robinson OJ, Overstreet C, Charney DR, Vytal K, Grillon C. Stress increases aversive prediction error signal in the ventral striatum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(10):4129–4133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(10):4129–4133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Smith DV, Rigney AE, Delgado MR. Distinct Reward Properties are Encoded via Corticostriatal Interactions. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:20093. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Frank MJ, Seeberger LC, O'Reilly RC. By carrot or by stick: Cognitive reinforcement learning in Parkinsonism. Science. 2004;306(5703):1940–1943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Kahneman D, Frederick S. Representativeness revisited: Attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. In: Gilovich T, Griffin D, Kahneman D, editors. Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 49–81. [Google Scholar]

40. Daw ND, Niv Y, Dayan P. Uncertainty-based competition between prefrontal and dorsolateral striatal systems for behavioral control. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(12):1704–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Dickinson A. Actions and habits: The development of behavioural autonomy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1985;308(1135):67–78. [Google Scholar]

Dickinson A. Actions and habits: The development of behavioural autonomy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1985;308(1135):67–78. [Google Scholar]

42. Reyna VF. How people make decisions that involve risk: A dual-processes approach. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13(2):60–66. [Google Scholar]

43. Yin HH, Ostlund SB, Knowlton BJ, Balleine BW. The role of the dorsomedial striatum in instrumental conditioning. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;22(2):513–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Yin HH, Knowlton BJ, Balleine BW. Inactivation of dorsolateral striatum enhances sensitivity to changes in the action-outcome contingency in instrumental conditioning. Behav Brain Res. 2006;166(2):189–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Schwabe L, Wolf OT. Stress prompts habit behavior in humans. J Neurosci. 2009;29(22):7191–7198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Schwabe L, Wolf OT. Socially evaluated cold pressor stress after instrumental learning favors habits over goal-directed action. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(7):977–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(7):977–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Schwabe L, Tegenthoff M, Hoffken O, Wolf OT. Simultaneous glucocorticoid and noradrenergic activity disrupts the neural basis of goal-directed action in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2012;32(30):10146–10155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. An fMRI study demonstrating a goal-directed to habit-based shift (and reduced OFC/mPFC reward valuation) with concurrent administration of hydrocortisone and yohimbe to mimic combined HPA/SMA activation.

48. Schwabe L, Wolf OT. Stress and multiple memory systems: from 'thinking' to 'doing'. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(2):60–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Vogel S, Fernandez G, Joels M, Schwabe L. Cognitive Adaptation under Stress: A Case for the Mineralocorticoid Receptor. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2016;20(3):192–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Joels M, Fernandez G, Roozendaal B. Stress and emotional memory: a matter of timing. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(6):280–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2011;15(6):280–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Hermans EJ, Henckens MJ, Joels M, Fernandez G. Dynamic adaptation of large-scale brain networks in response to acute stressors. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37(6):304–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):410–422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Otto AR, Raio CM, Chiang A, Phelps EA, Daw ND. Working-memory capacity protects model-based learning from stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(52):20941–20946. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. A reinforcement-learning study demonstrating that acute stress impaired model-based (i.e., goal-directed) but not model-free (i.e., habit-based) choice, and that greater working memory capacity protected against a model-based impairment.

54. Dolan RJ, Dayan P. Goals and Habits in the Brain. Neuron. 2013;80(2):312–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Kozena L, Frantik E. Psychological and physiological response to job stress in emergency ambulance personnel. Homeostasis in Health and Disease. 2001;41(3-4):121–122. [Google Scholar]

Kozena L, Frantik E. Psychological and physiological response to job stress in emergency ambulance personnel. Homeostasis in Health and Disease. 2001;41(3-4):121–122. [Google Scholar]

56. Gunnar M, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:145–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Coates JM, Gurnell M, Sarnyai Z. From molecule to market: steroid hormones and financial risk-taking. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2010;365(1538):331–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Ellsberg D. Risk, Ambiguity and the Savage Axioms. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1961;75(4):643–669. [Google Scholar]

59. Kahneman D, Tversky A. Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist. 1984;39(4):341–350. [Google Scholar]

60. Sanfey AG, Loewenstein G, McClure SM, Cohen JD. Neuroeconomics: cross-currents in research on decision-making. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10(3):108–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Krain AL, Wilson AM, Arbuckle R, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Distinct neural mechanisms of risk and ambiguity: A meta-analysis of decision-making. Neuroimage. 2006;32(1):477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krain AL, Wilson AM, Arbuckle R, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Distinct neural mechanisms of risk and ambiguity: A meta-analysis of decision-making. Neuroimage. 2006;32(1):477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Hsu M, Bhatt M, Adolphs R, Tranel D, Camerer CF. Neural systems responding to degrees of uncertainty in human decision-making. Science. 2005;310(5754):1680–1683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Platt ML, Huettel SA. Risky business: the neuroeconomics of decision making under uncertainty. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11(4):398–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Starcke K, Wolf OT, Markowitsch HJ, Brand M. Anticipatory stress influences decision making under explicit risk conditions. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122(6):1352–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. A review of the acute stress and DM literature, proposing stress effects be grouped by: dysfunctional strategy use, insufficient adjustment from automatic response, altered feedback processing, and altered reward/punishment sensitivity.

65. Pabst S, Schoofs D, Pawlikowski M, Brand M, Wolf OT. Paradoxical effects of stress and an executive task on decisions under risk. Behav Neurosci. 2013;127(3):369–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Buckert M, Schwieren C, Kudielka BM, Fiebach CJ. Acute stress affects risk taking but not ambiguity aversion. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2014;8:82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Bendahan S, Goette L, Thoresen J, Loued-Khenissi L, Hollis F, Sandi C. Acute stress alters individual risk taking in a time-dependent manner and leads to anti-social risk. Eur J Neurosci. 2016 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Porcelli AJ, Delgado MR. Acute stress modulates risk taking in financial decision making. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(3):278–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Pabst S, Brand M, Wolf OT. Stress effects on framed decisions: there are differences for gains and losses. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2013;7:142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Clark L, Li RR, Wright CM, Rome F, Fairchild G, Dunn BD, et al. Risk-avoidant decision making increased by threat of electric shock. Psychophysiology. 2012;49(10):1436–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clark L, Li RR, Wright CM, Rome F, Fairchild G, Dunn BD, et al. Risk-avoidant decision making increased by threat of electric shock. Psychophysiology. 2012;49(10):1436–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Preston SD, Buchanan TW, Stansfield RB, Bechara A. Effects of anticipatory stress on decision making in a gambling task. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121(2):257–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. van den Bos R, Harteveld M, Stoop H. Stress and decision-making in humans: performance is related to cortisol reactivity, albeit differently in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(10):1449–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Lighthall NR, Sakaki M, Vasunilashorn S, Nga L, Somayajula S, Chen EY, et al. Gender differences in reward-related decision processing under stress. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2011;7(4):476–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Lighthall NR, Mather M, Gorlick MA. Acute stress increases sex differences in risk seeking in the balloon analogue risk task. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Schubert R, Gysler M, Brown M, Brachinger H-W. Gender specific attitudes towards risk and ambiguity: an experimental investigation. Zurich: Center for Economic Research, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology; 2000. [Google Scholar]

76. Starcke K, Brand M. Effects of Stress on Decisions Under Uncertainty: A Meta-Analysis. P. sychol Bull. 2016;142(9):909–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Phuong A, Galvan A. Acute Stress Increases Risky Decisions and Dampens Prefrontal Activation Among Adolescent Boys. Neuroimage. 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Galvan A, McGlennen KM. Daily stress increases risky decision-making in adolescents: A preliminary study. Developmental Psychobiology. 2012;54(4):433–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RAR, Updegraff JA. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review. 2000;107(3):411–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychological Review. 2000;107(3):411–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Qin S, Cousijn H, Rijpkema M, Luo J, Franke B, Hermans EJ, et al. The effect of moderate acute psychological stress on working memory-related neural activity is modulated by a genetic variation in catecholaminergic function in humans. Front Integr Neurosci. 2012;6:16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Sokol-Hessner P, Raio CM, Gottesman S, Lackovic SF, Phelps EA. Acute stress does not affect risky monetary decision-making. Neurobiology of Stress. 2016;5:19–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Lempert KM, Porcelli AJ, Delgado MR, Tricomi E. Individual differences in delay discounting under acute stress: the role of trait perceived stress. Front Psychol. 2012;3:251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Sokol-Hessner P, Lackovic SF, Tobe RH, Camerer CF, Leventhal BL, Phelps EA. Determinants of Propranolol's Selective Effect on Loss Aversion. Psychological Science. 2015;26(7):1123–1130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2015;26(7):1123–1130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Vinkers CH, Zorn JLV, Cornelisse S, Koot S, Houtepen LC, Olivier B, et al. Time-dependent changes in altruistic punishment following stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(9):1467–1475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Steinbeis N, Engert V, Linz R, Singer T. The effects of stress and affiliation on social decision-making: Investigating the tend-and-befriend pattern. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:138–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. FeldmanHall O, Raio CM, Kubota JT, Seiler MG, Phelps EA. The Effects of Social Context and Acute Stress on Decision Making Under Uncertainty. Psychological Science. 2015;26(12):1918–1926. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Margittai Z, Strombach T, van Wingerden M, Joels M, Schwabe L, Kalenscher T. A friend in need: Time-dependent effects of stress on social discounting in men. Hormones and Behavior. 2015;73:75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Raio CM, Orederu TA, Palazzolo L, Shurick AA, Phelps EA. Cognitive emotion regulation fails the stress test. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(37):15139–15144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Raio CM, Orederu TA, Palazzolo L, Shurick AA, Phelps EA. Cognitive emotion regulation fails the stress test. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(37):15139–15144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Maier SU, Makwana AB, Hare TA. Acute Stress Impairs Self-Control in Goal-Directed Choice by Altering Multiple Functional Connections within the Brain's Decision Circuits. Neuron. 2015;87(3):621–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Speer ME, Bhanji JP, Delgado MR. Savoring the past: positive memories evoke value representations in the striatum. Neuron. 2014;84(4):847–856. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Bhanji JP, Kim ES, Delgado MR. Perceived control alters the effect of acute stress on persistence. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2016;145(3):356–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stress changes how people make decisions -- ScienceDaily

Science News

from research organizations

- Date:

- February 28, 2012

- Source:

- Association for Psychological Science

- Summary:

- Trying to make a big decision while you're also preparing for a scary presentation? You might want to hold off on that.

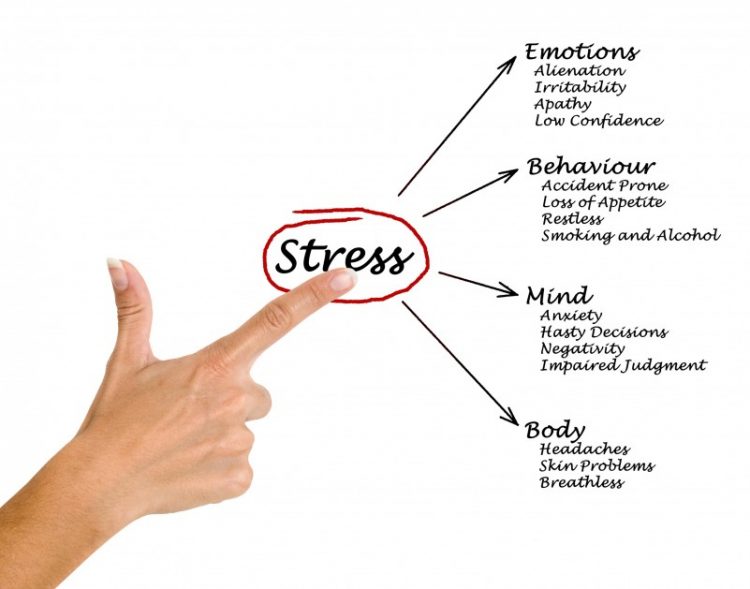

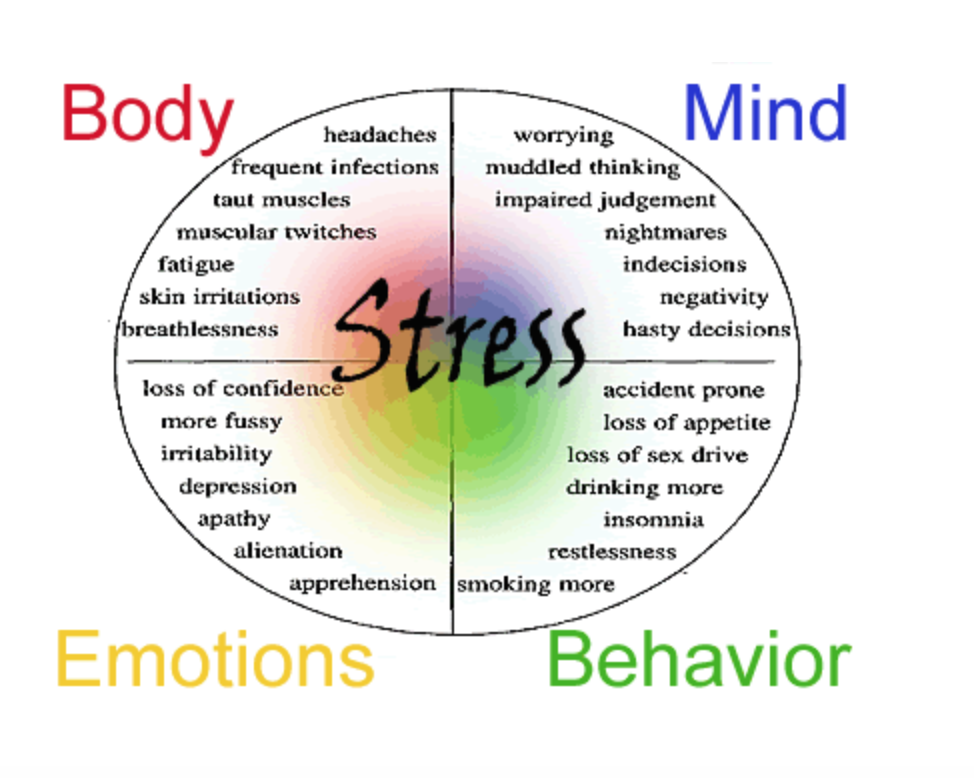

Feeling stressed changes how people weigh risk and reward. A new article published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, reviews how, under stress, people pay more attention to the upside of a possible outcome.

Feeling stressed changes how people weigh risk and reward. A new article published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, reviews how, under stress, people pay more attention to the upside of a possible outcome. - Share:

-

Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIN Email

FULL STORY

Trying to make a big decision while you're also preparing for a scary presentation? You might want to hold off on that. Feeling stressed changes how people weigh risk and reward. A new article published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, reviews how, under stress, people pay more attention to the upside of a possible outcome.

advertisement

It's a bit surprising that stress makes people focus on the way things could go right, says Mara Mather of the University of Southern California, who cowrote the new review paper with Nichole R. Lighthall. "This is sort of not what people would think right off the bat," Mather says. "Stress is usually associated with negative experiences, so you'd think, maybe I'm going to be more focused on the negative outcomes."

Lighthall. "This is sort of not what people would think right off the bat," Mather says. "Stress is usually associated with negative experiences, so you'd think, maybe I'm going to be more focused on the negative outcomes."

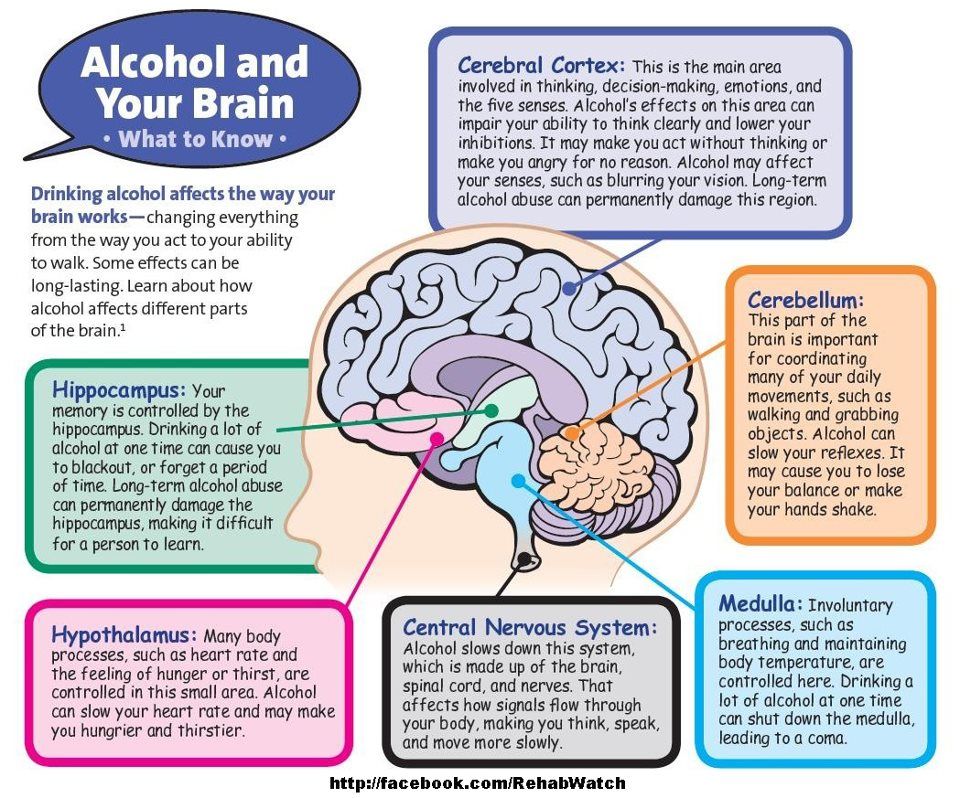

But researchers have found that when people are put under stress -- by being told to hold their hand in ice water for a few minutes, for example, or give a speech -- they start paying more attention to positive information and discounting negative information. "Stress seems to help people learn from positive feedback and impairs their learning from negative feedback," Mather says.

This means when people under stress are making a difficult decision, they may pay more attention to the upsides of the alternatives they're considering and less to the downsides. So someone who's deciding whether to take a new job and is feeling stressed by the decision might weigh the increase in salary more heavily than the worse commute.

The increased focus on the positive also helps explain why stress plays a role in addictions, and people under stress have a harder time controlling their urges. "The compulsion to get that reward comes stronger and they're less able to resist it," Mather says. So a person who's under stress might think only about the good feelings they'll get from a drug, while the downsides shrink into the distance.

"The compulsion to get that reward comes stronger and they're less able to resist it," Mather says. So a person who's under stress might think only about the good feelings they'll get from a drug, while the downsides shrink into the distance.

Stress also increases the differences in how men and women think about risk. When men are under stress, they become even more willing to take risks; when women are stressed, they get more conservative about risk. Mather links this to other research that finds, at difficult times, men are inclined toward fight-or-flight responses, while women try to bond more and improve their relationships.

"We make all sorts of decisions under stress," Mather says. "If your kid has an accident and ends up in the hospital, that's a very stressful situation and decisions need to be made quickly." And, of course, big decisions can be sources of stress all by themselves and just make the situation worse. "It seems likely that how much stress you're experiencing will affect the way you're making the decision. "

"

make a difference: sponsored opportunity

Story Source:

Materials provided by Association for Psychological Science. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- M. Mather, N. R. Lighthall. Risk and Reward Are Processed Differently in Decisions Made Under Stress. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2012; 21 (1): 36 DOI: 10.1177/0963721411429452

Cite This Page:

- MLA

- APA

- Chicago

Association for Psychological Science. "Stress changes how people make decisions." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 28 February 2012. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/02/120228114308.htm>.

Association for Psychological Science. (2012, February 28). Stress changes how people make decisions. ScienceDaily. Retrieved December 28, 2022 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/02/120228114308.htm

ScienceDaily. Retrieved December 28, 2022 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/02/120228114308.htm

Association for Psychological Science. "Stress changes how people make decisions." ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/02/120228114308.htm (accessed December 28, 2022).

advertisement

How does stress affect decision making?

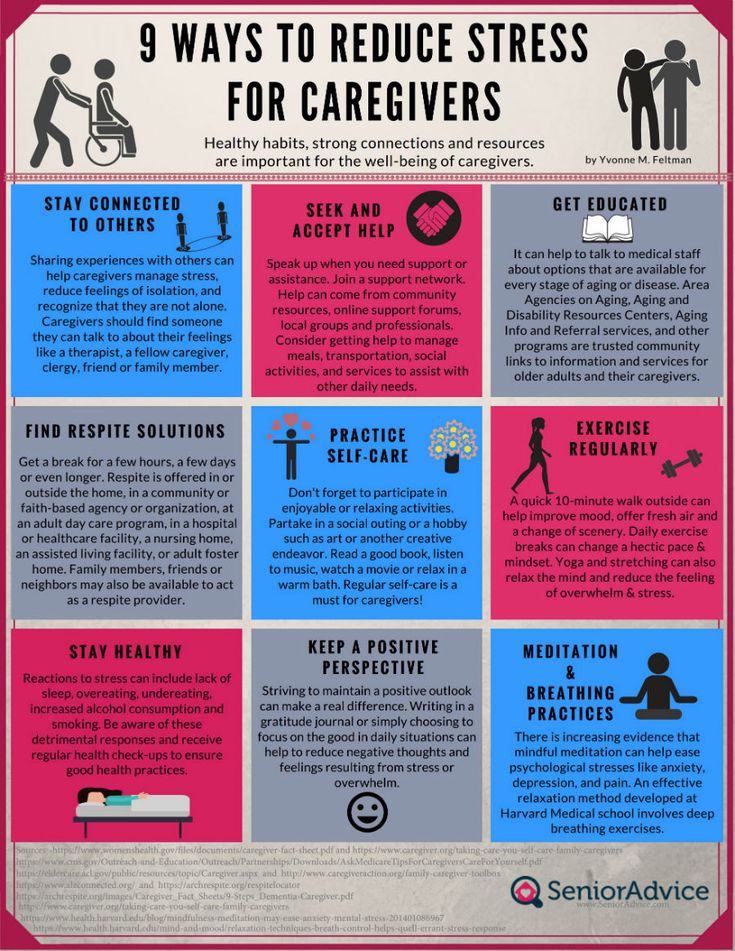

Every year, the scientific community pays more and more attention to the impact of stress on the physiological and mental characteristics of not only humans, but also animals. It was in studies on rats a few years ago that it was possible to show that the nerve centers responsible for pleasure, decision-making, motivation, are directly connected with the cortical centers that control mood, and that if the connection between them is broken, then animals will be more willing to put themselves at risk. if they end up with a big reward. That is, a hypothesis arose that the brain in a state of stress can make more risky decisions than in a state of rest. New experiments by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA, have confirmed that stress itself makes you take risks. The research results are published in the scientific journal Cell. nine0003

New experiments by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA, have confirmed that stress itself makes you take risks. The research results are published in the scientific journal Cell. nine0003

Scientists compared the behavior of mice in a Y-shaped maze. When they were put into a maze where they could take two paths, in one case the animals received thick chocolate milk, but they had to endure exposure to very bright light. In another case, the light was dim, but the milk was not so tasty, and the rodents chose the first option only half the time.

But if the mice were previously immersed in prolonged stress (for this they were given trouble every day for 2 weeks), then they mostly rushed to the bright light, although it should have seemed dangerous to them. And even when the milk in the chamber with dim light became more delicious, they still continued to take risks. Everything looked as if the nerve centers responsible for motivation and pleasure stopped issuing restrictive commands. Due to stress, their decisions became careless - the centers of pleasure and motivation were activated too much, and the animals stopped feeling fear. nine0003

Due to stress, their decisions became careless - the centers of pleasure and motivation were activated too much, and the animals stopped feeling fear. nine0003

One of the authors of the study, Ann Graybiel, believes that the reason for this behavior is that stress suppresses the activity of neurons in the cerebral cortex. In this case, it is most likely that the nerve cells of the anterior part of the brain responsible for making the optimal decision are suppressed. In addition, regular overexcitation of motivational centers can create a persistent pattern in the brain, as a result of which unintelligent behavior can persist for months, although mice will not be subjected to any stress. At the same time, it is possible to restore normal nerve chains by recreating the correct connection between the nerve centers. nine0003

All this is similar to human behavior, when, under the pressure of circumstances, a person suddenly commits some risky impulsive acts, abuses alcohol or some other substances, and generally behaves extremely irrationally. Most likely, in the human brain, stress acts in the same way as in the mouse, preventing the cortex from influencing motivational centers that begin to indulge in pleasure without respite, even if this entails serious risk. It is possible that such behavior could be corrected by acting pharmacologically or by some other method on the corresponding neural circuits. nine0003

Most likely, in the human brain, stress acts in the same way as in the mouse, preventing the cortex from influencing motivational centers that begin to indulge in pleasure without respite, even if this entails serious risk. It is possible that such behavior could be corrected by acting pharmacologically or by some other method on the corresponding neural circuits. nine0003

Based on www.sciencedaily.com

How to make effective decisions | The Workstream

Every day is a constant choice.

Which route to go to work? What is the first task to cross off the to-do list? Sit down to work at your desk or in a common area? What to bring for a colleague's birthday?

And then there are the big career or corporate decisions that keep you awake at night, like how much to price a product or what features to release in the next release. nine0003

You are making decision after decision all the time, and gradually it can start to weigh on you. (Formally, this phenomenon is known as decision fatigue, i.e., decision fatigue. Remember the term if you want to show off your erudition at the next quiz.)

(Formally, this phenomenon is known as decision fatigue, i.e., decision fatigue. Remember the term if you want to show off your erudition at the next quiz.)

Fear not, there is good news: decision making should not be so exhausting and disturbing. Working through your decision-making process will help you make effective judgments without worry.

Are you interested? We thought so. Now we will tell you about everything you need to know in order to make positive and painless decisions. nine0003

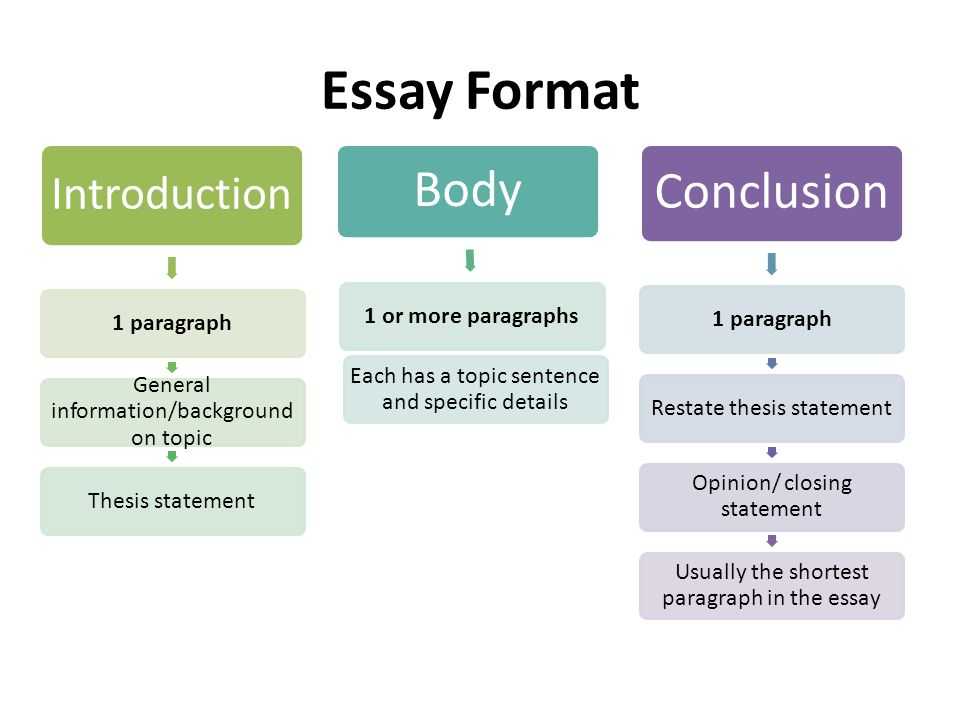

What is decision making?

We don't need to tell you what decision making is, but we'll do it anyway. It is the mental process you go through to make a choice or determine a course of action. This applies to both small decisions (like what music to listen to on the road) and big ones (like whether to move for a job). You go through such a process both in the case of an independent choice, and when making a decision together with your team. nine0003

Let's stick to a simple example to be specific: you're trying to decide whether to have a salad or a burrito for a snack.

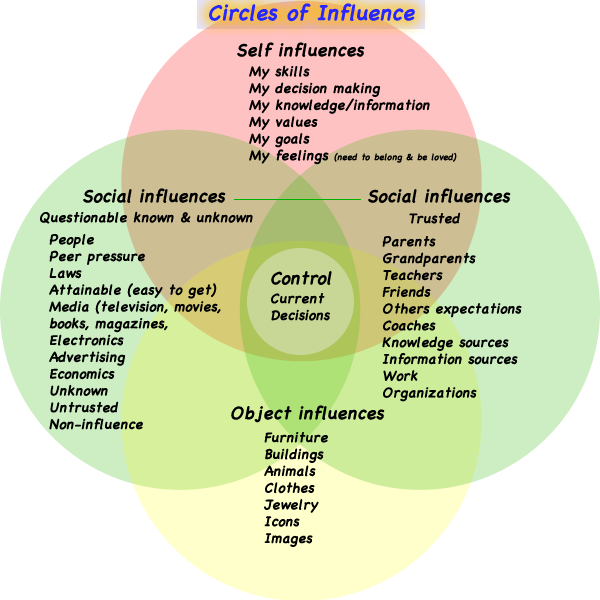

To make a choice, you go over the various actions in your mind. Perhaps you are evaluating some criteria, such as what is cheaper or what you ate most recently. Maybe you ask your team members for their opinion, who might also order something for themselves.

All of these (and more!) are part of the decision process, the series of steps you take to determine your final choice. nine0003

For these everyday and seemingly unimportant situations, everything looks quite simple. After all, no matter how delicious it is, one burrito most often does not change your life.

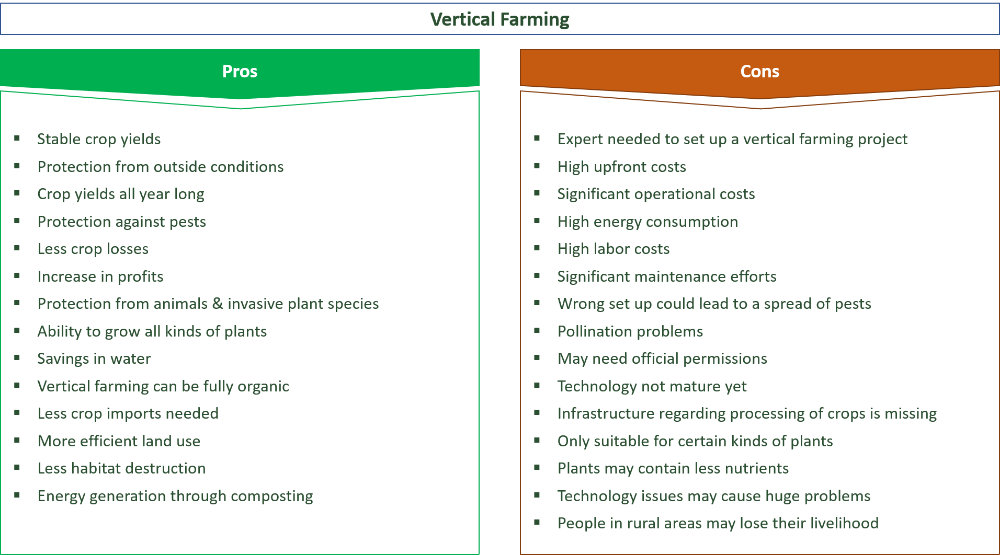

But more complex solutions often require more complex processes. That is why there are so many different methods and decision-making models, from the good old list of pros and cons to a matrix that helps to weigh all the options. We'll take a closer look at some of the common methods in a bit. nine0003

Benefits. Why good decision-making is a plus

When you're sweating from the need to make a choice, it's unlikely that evaluating and refining your decision-making process will seem timely.

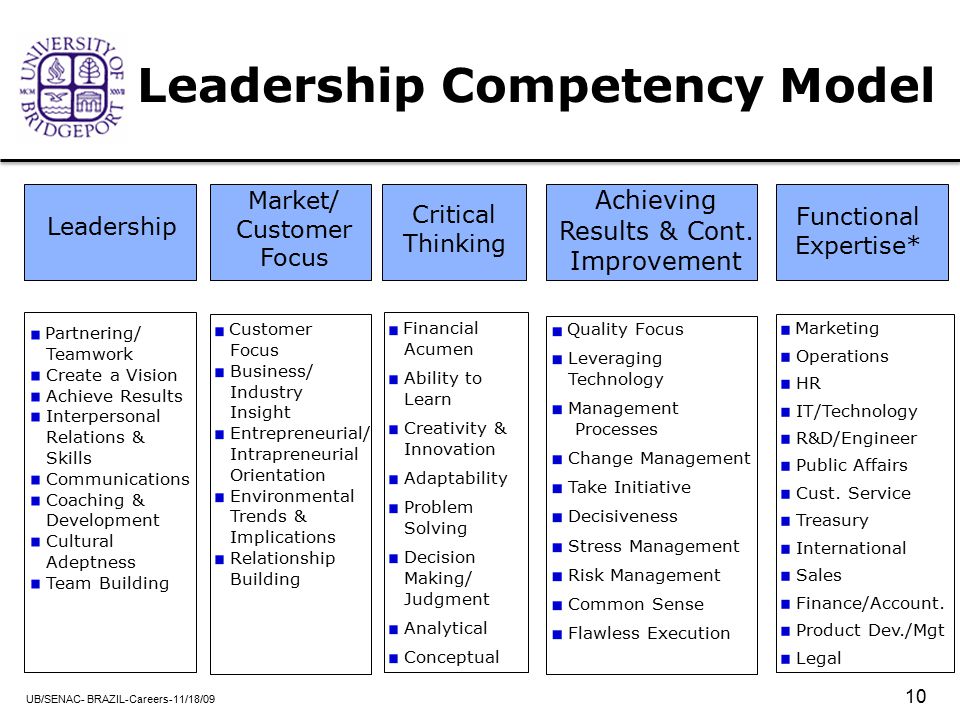

And this is understandable. However, when you have a sound decision-making process in place, there are many benefits, including: This turns out to be difficult (which is why this guide exists). To make a choice requires strong critical thinking skills, because in order to decide which way to go, you have to collect and analyze information. nine0003

Do more things

How much time could you save if you didn't have to agonize over your choice each time? Strengthening decision-making skills greatly increases your productivity: you will be confident in the direction you choose, spending less time and much less nerves on the decision.

More trust and confidence

The ability to make quick and well-informed decisions creates a calm mood in your team. Without this ability, the team is in perpetual hesitation over what to do next. Think about it: how much will you trust a leader who, apparently, cannot make a choice and lead you through a difficult stage of work? Not very much, right? This may be why 63% of employees say their supervisors are partially or completely untrustworthy. nine0003

nine0003

Decision models to speed up thought processes

So, you already understood that effective decision making is an important thing. However, it cannot be said that this thing is simple.

The comfort is that you don't have to invent anything. Here you will find some of the most common decision making models, a summary of what they are, and possible issues to look out for.

Vroom-Yetton-Iago Decision Model

In fact, such a model does not lead you to the final choice. But this is a great start that will help you understand what to do next. The model will prompt one of five possible decision-making processes, which, in turn, can lead you to the final goal.

This model is useful when you need to make a decision for your entire team. The exercise will begin with yes or no answers to a series of seven different questions. As you walk through the decision tree, you'll get a code that defines the ideal decision path for you and your team. MindTools, an executive resource website, explains that the options are as follows. nine0003

MindTools, an executive resource website, explains that the options are as follows. nine0003

- Autocratic (A1). You are relying on information (not additional suggestions from your team) to make a decision.

- Autocratic (A2). You communicate with the team to get more details and then make the final choice.

- Advisory (C1). You will get the opinions of team members individually, without group discussions. You then use this information to make the final decision. nine0094

- Advisory (C2). You bring the whole team together to discuss a decision in a group, and then use the information received to make a decision yourself.

- Joint (G2). You work with your team to reach a group consensus on the best way forward. Your job is to lead the discussion, not make the final choice yourself.

This model relieves the overwhelming feeling that you are paralyzed by your decision, as it indicates some actionable options for moving forward. However, some critics consider it somewhat harsh and leaves you no way to customize the algorithm to suit your situation or opinion. nine0003

However, some critics consider it somewhat harsh and leaves you no way to customize the algorithm to suit your situation or opinion. nine0003

Ladder of Conclusions

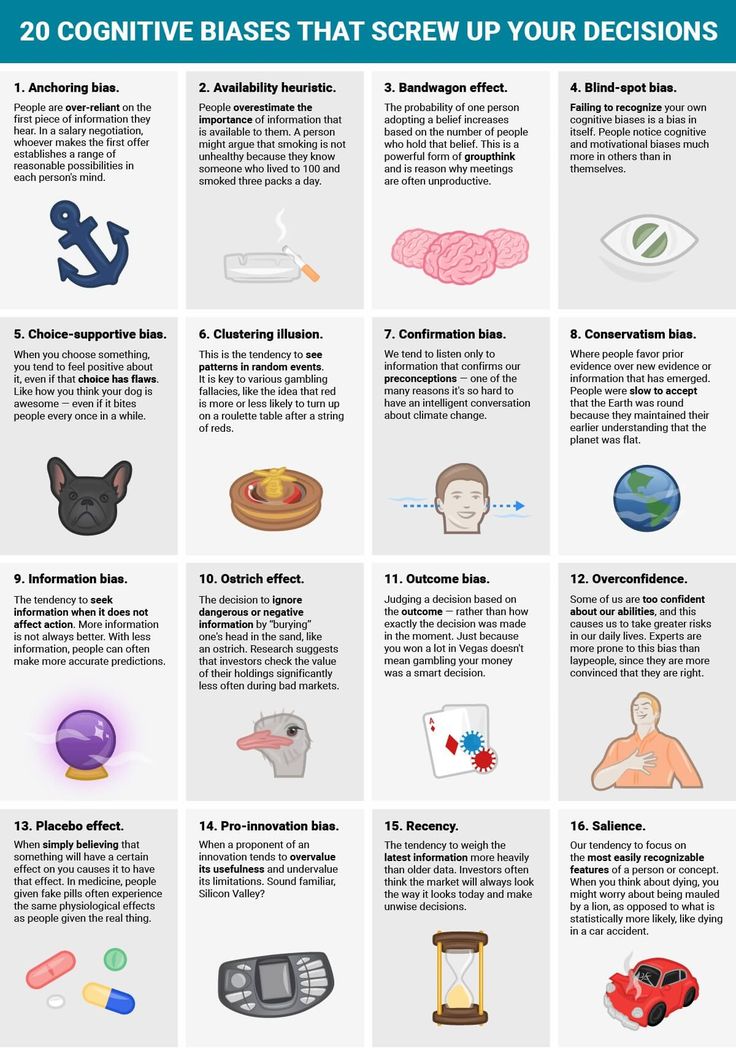

It's easy to jump to conclusions when making decisions, but the Ladder of Conclusions shows the thought process you must go through in order not to be trapped by your own biases and assumptions.

Using this method, start at the bottom of the stairs and work your way up without skipping steps. Suggested steps include:

- view data;

- data selection;

- giving meaning to data; nine0094

- preparation of assumptions based on this sense;

- conclusions;

- acceptance of beliefs based on the conclusions drawn;

- transition to action.

As you work your way through each step, you will be able to fight the natural urge to jump to conclusions. The problem with this model is that we tend to choose data that supports our existing assumptions. This phenomenon is known as a recursive loop.

This phenomenon is known as a recursive loop.

For example, if you have the impression that one of your team members is lazy, you may pay more attention to her shortcomings in her work and completely lose sight of her real achievements. nine0003

Model DACI

You don't always have to make decisions on your own. In the workplace, many of the decisions you make affect other team members and other departments, which means you have to deal with a lot of opinions and ideas (often conflicting) about which path to take.

We at Atlassian are very fond of using the DACI model, clarifying the roles in group decision making (so that seven nannies do not have a child without an eye). nine0003

With this model, you can assign different roles to people.

- Driver The only person who is responsible for engaging all stakeholders, collecting the necessary information and obtaining decisions at each control point.

- Approver.

The only person who makes the final decision.

The only person who makes the final decision. - Contributors. These people can express their opinion, but they do not vote. They provide their knowledge and experience that can influence the decision. nine0094

- Informed. These people are not active participants in the process, but receive information about the final choice.

All this is necessary so that everyone knows what their role is and what their powers are. On the other hand, it may cause people to fear crossing the line, and they will eventually refuse to actively participate in the decision-making process.

Decision Matrix

One of the most difficult aspects of decision making is dealing with multiple variables. For example, if you're choosing between two freelancers for a copywriting project, you'll need to think about their experience, cost, and future availability. nine0003

What if one of the freelancers seems like a great fit for the job, but doesn't look great in all of these categories? How then can you choose?

The Decision Matrix requires you to assign a weight (essentially a level of importance) to each of the factors you consider, and then do some simple calculations to make the choice that best satisfies all the criteria.

This is a great way to evaluate all the important aspects that can affect your choice, but it can get biased. We're not saying this will happen to you, but it's very easy to give certain factors more weight than others without even realizing the reasons, and that can affect the end result. nine0003

Improve your decision-making skills

What else, besides relying on methods, will help you become an expert decision-maker?

Start by assessing your current decision-making skills. Use this brief outline to evaluate your existing approach and determine where you need to work on.

Whatever your result, there are a number of tips that can always come in handy. So, here are a few important things to keep in mind to help you make better decisions. nine0003

Beware of bias

You may have noticed that we mentioned bias or jumping to conclusions several times in our discussion of different decision models. This is because the assumptions in your head can interfere with the process and undermine the ability to make intelligent decisions.

Cognitive biases occur naturally and cannot be completely avoided. One of the best ways to keep them in check is to constantly critically evaluate the information that you base your choices on. nine0003

For example, if you are already sure that a team member cannot contribute to a shared project, ask yourself why. Did he say he was too busy, or did you assume that? Does he really not have the experience that is required, or did you not begin to delve into what he can do?

Test yourself to be as objective as possible. And it never hurts to voice your thoughts in front of someone else to get an unbiased opinion.

Follow the data

Another great way to avoid bias is to rely on data when making decisions.

Can you find statistics on a similar project completed in the past? Is there feedback on what went well and what didn't? Are there any analytical conclusions that would support one option against the background of another?

When hard facts can be gathered, the data doesn't lie, making it an excellent anti-bias defense that can be relied upon in decision making. nine0003

nine0003

Consider the short and long term implications

When you're stuck in the middle of a decision, limited vision is almost inevitable. You are so focused on the process of choosing your path that you forget to think about the consequences of your choice.

Imagine that you are deciding whether to extend the deadline for a project the team is working on. Time is running out and you're afraid you won't be able to finish by the deadline.

If you're only thinking about short-term effects, shifting the timeline seems like the obvious solution. You'll take some of the pressure off, get more time to do quality work, and make the team feel like you're on their side.

But if you change your perspective and look at long-term effects, there are many more questions to consider. A shift in schedule will no doubt push back the next projects you have planned, and you will begin to form the perception that deadlines are suggestions, not requirements. nine0003

Thinking about the short and long term, of course, complicates things a bit (we know that's the last thing you want), but it helps you make the best, most logical decision.

Communicate openly with your team

When the decision is finally made, you want the team to come together and step on the gas.

But there's one point: your team won't be rushing to implement your solution if they don't fully understand the accompanying context. nine0003

So when you come to a conclusion, explain to the team how the decision was made. What factors did you take into account? What are you trying to achieve along the way?

If your team knows the details of the decision, everyone can feel like they are part of the process (rather than receiving instructions from outside) and do their job better in the context of the choice made. In one 2015 survey, 57% of respondents said they would be better at their job if they understood where the company was heading. nine0003

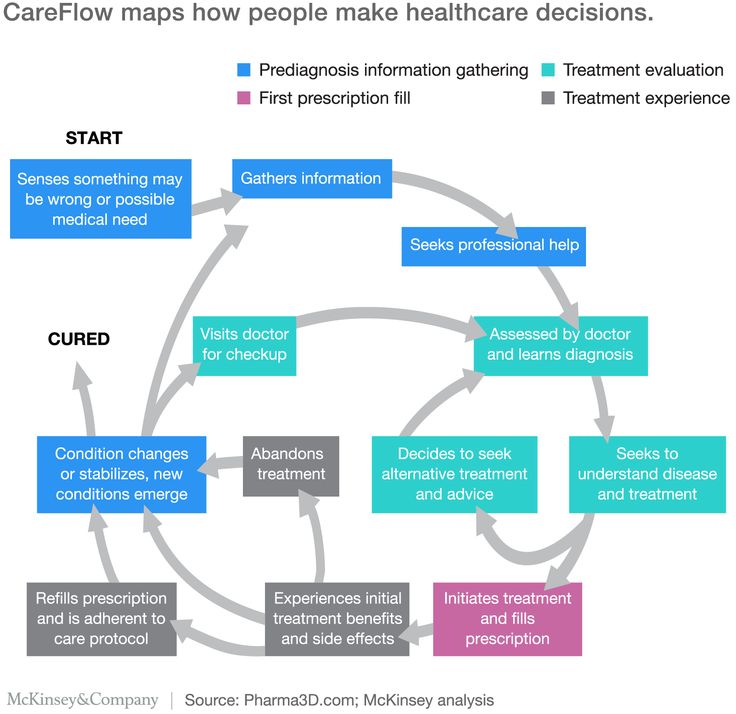

How decision making works in project management

We have already discussed a lot on the topic of decision making. Let's now bring it all down to a few simple steps that you can follow.

Remember that all the models and tips we have already mentioned can be incorporated into the main process, which will be discussed below. Think of these steps as a template that you can customize or add to depending on the specific choice you need to make. nine0003

Let's say you set aside a budget to add a new member to your team. You have many needs, and you need to decide which position the employee needs the most. Here are seven steps to follow.

- Determine the purpose of the decision. Decide which employee to hire next.

- Gather the information you need. What projects are on your team's schedule? What experience is lacking to fulfill them? What kind of specialists now have to attract from the outside? nine0094

- Define options. After thinking about the information, you've narrowed it down to a graphic designer, copywriter, or SEO specialist.

- Evaluate the options. It's time to weigh all the options.

Maybe one of the competencies is easily covered by an existing team member? What is the most pressing need for the team?

Maybe one of the competencies is easily covered by an existing team member? What is the most pressing need for the team? - Make your choice. After considering all the information, you have decided to hire a graphic designer. nine0094

- Take action. Hooray! Post a vacancy and find such a member in the team.

- Evaluate your decision. Ask the team to provide feedback on the decision and form conclusions that can be used next time.

This is the process of decision making in project management in its simplest form. But it has room to add other elements from those we discussed earlier.

For example, you can use a decision matrix when you need to evaluate options. Or maybe you will deliberately remove your own bias against hiring another copywriter and leave this option because you realize that existing copywriters are working to the limit. nine0003

Remember that the above describes decision making in its most basic form.