Avoidant coping definition

Does Avoidance Coping Work or Just Cause More Stress?

Skip to contentPublished: February 5, 2022 Updated: September 28, 2022

Published: 02/05/2022 Updated: 09/28/2022

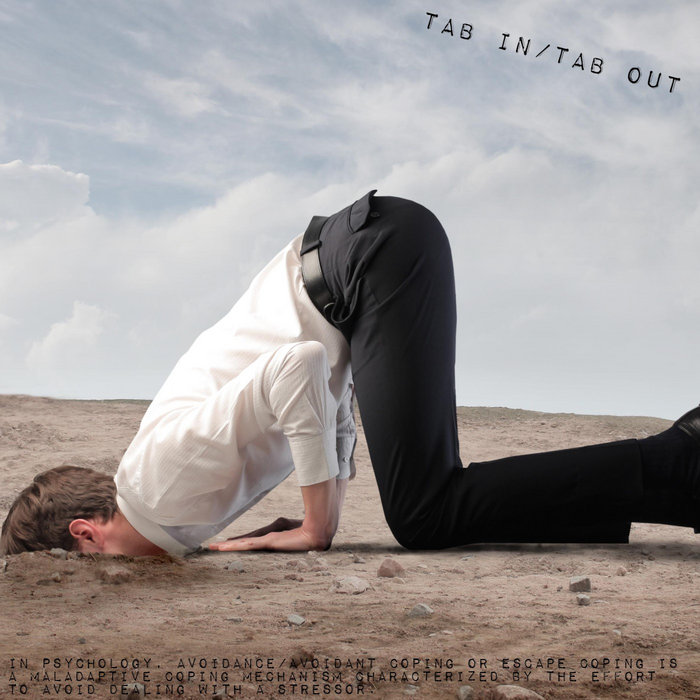

Avoidance coping strategies involve avoiding stressful situations, experiences, or difficult thoughts and feelings as a way to cope.1,2 While avoidance provides short-term relief, overusing it can cause more stress.1,3,4Ignoring or denying problems, procrastinating, canceling plans, or using substances are all examples of avoidance-focused coping skills.2,5

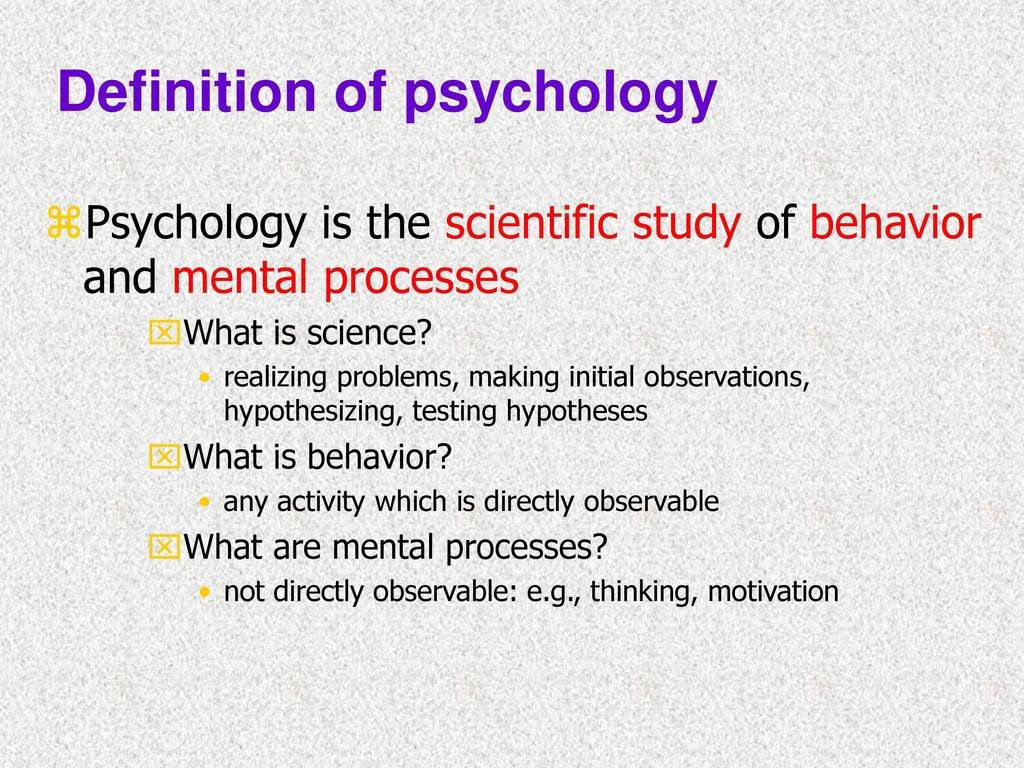

What Is Avoidance Coping?

Avoidance coping temporarily reduces stress by avoiding the situations, thoughts, or feelings that cause or contribute to it.1,2

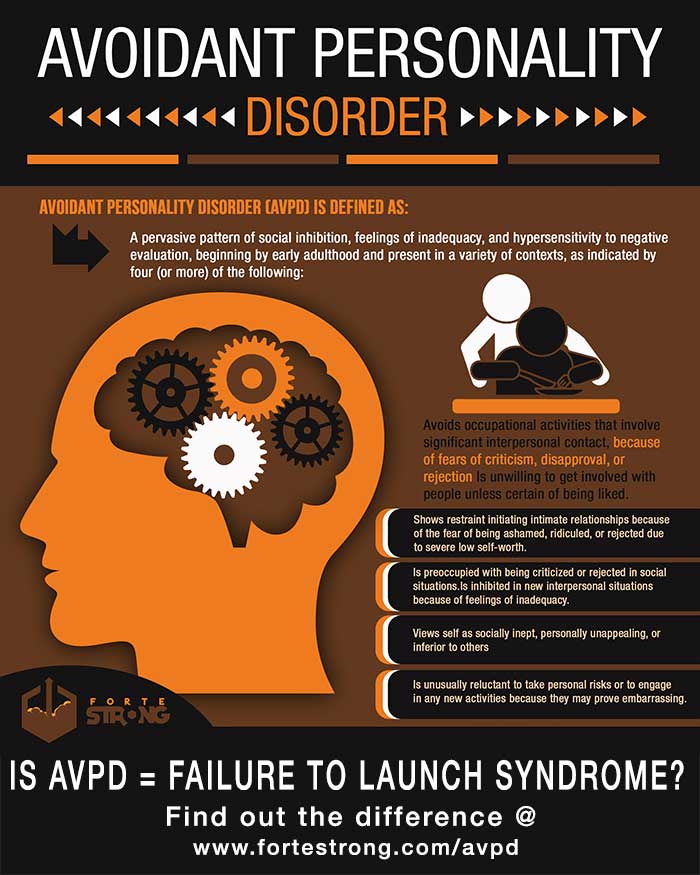

4 Some people use cognitive avoidance strategies to distract themselves, ignore problems, or not worry or deal with their stress. Others rely on behavioral avoidance strategies like avoiding people, places, and situations that cause stress or anxiety. 1,2

Avoidance coping is generally viewed as unhealthy and ineffective because being avoidant doesn’t address root causes of stress, and tends to increase stress and anxiety when overused. Most avoidant coping skills are efforts to find instant relief from stress, even when it makes things worse in the long run.

Research indicates that avoidance coping has many unwanted consequences, including lowered self-esteem, higher stress, and poorer physical and mental health.1,2,3,4

What are you trying to avoid? Would it be helpful to talk with a therapist about it? BetterHelp has over 20,000 licensed therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. BetterHelp starts at $60 per week. Complete a brief questionnaire and get matched with the right therapist for you.

Choosing Therapy partners with leading mental health companies and is compensated for referrals by BetterHelp

Visit BetterHelp

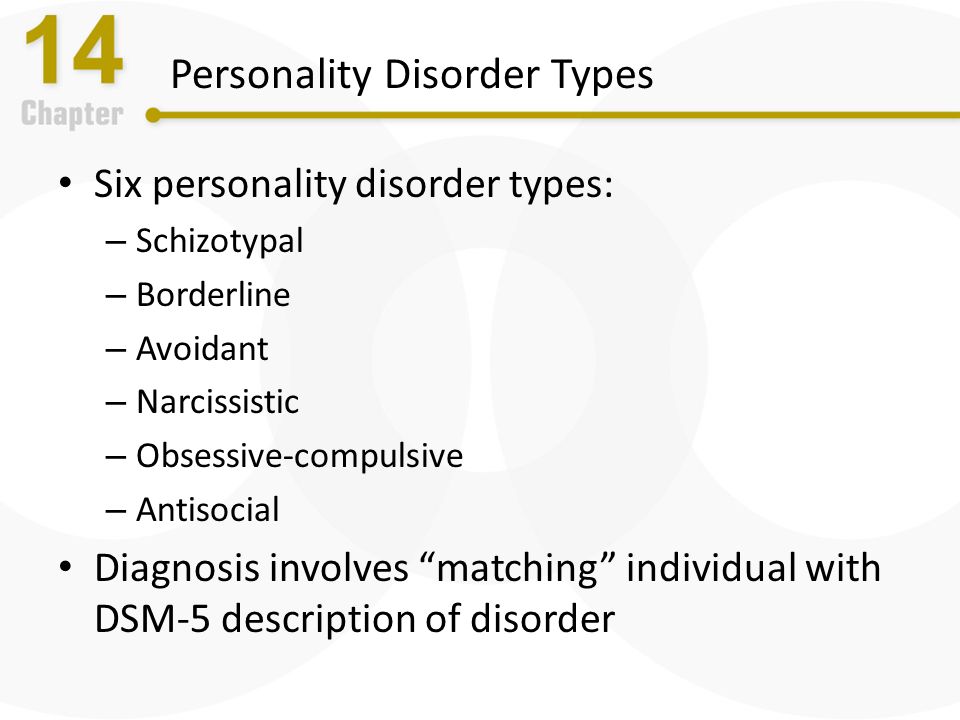

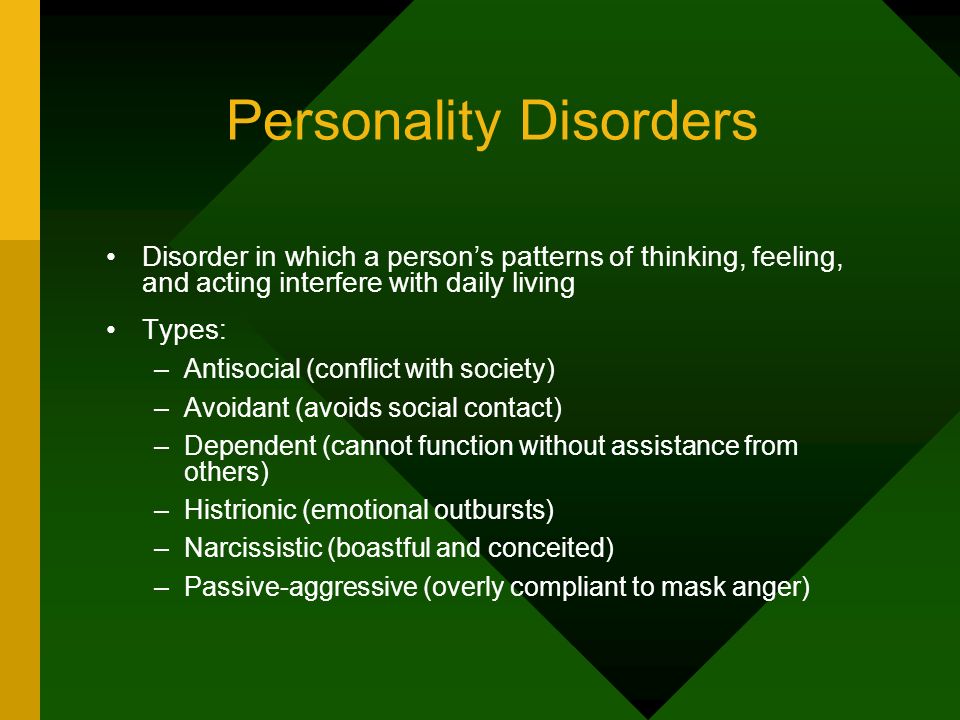

Types of Coping Styles & Strategies

A lot of the research on avoidance as a coping mechanism suggests that most people cope in one of two ways: by either approaching or avoiding the sources of stress. Approach coping styles are (usually) healthier and more effective than avoidance coping styles.1,3

Approach coping styles are (usually) healthier and more effective than avoidance coping styles.1,3

Approach vs. Avoidance Coping Styles

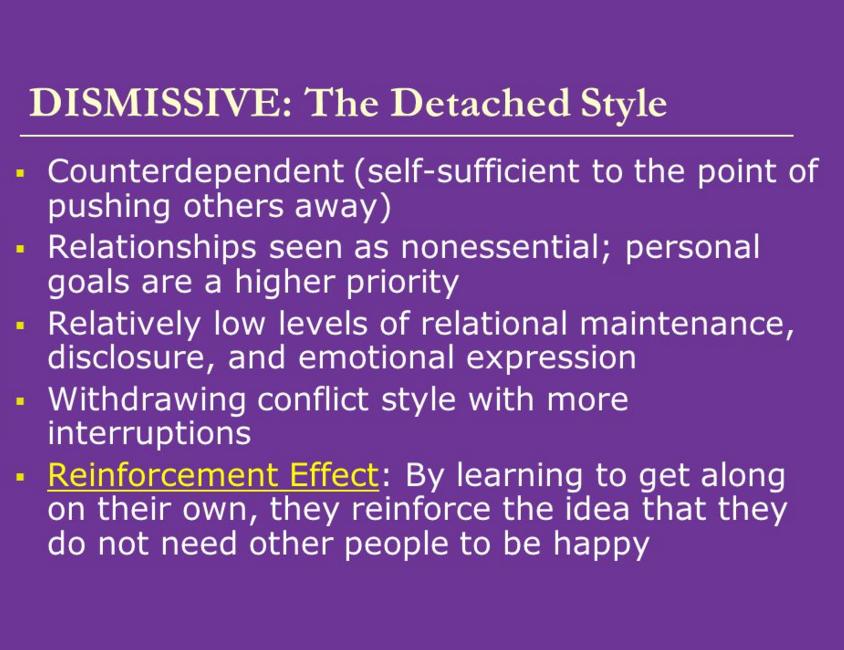

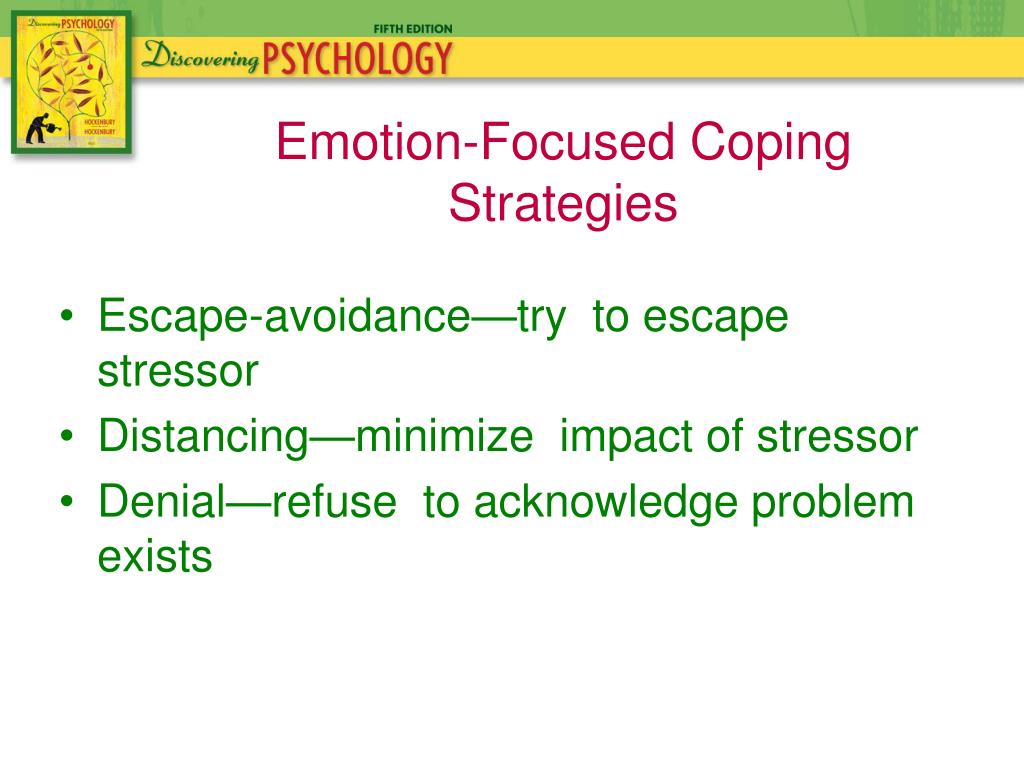

Most healthy coping skills don’t just reduce stress; instead, they directly address the problems causing it. These active coping skills are used by people with an approach-focused or problem-focused coping style. Most unhealthy coping skills are used by people with an avoidance- or emotion-focused coping style that aims to lessen stress and feel better in the moment.1,2,4,5

Here are key differences between approach and avoidant coping styles:1,4,5,6,7

Approach coping styles are defined by:

- Directly confronts the problem/issue

- Is a proactive and active coping method

- Uses resources, skills, and supports

- Is linked to higher self-control

- Uses a problem-solving approach

- Focuses on controllable aspects of the issue

- Finds ways to improve the situation

- Leads to long-term stress reduction and stress management

- Boosts confidence and self-efficacy

- Works through difficult emotions

Avoidant coping styles are defined by:

- Avoids, denies, or escapes the problem/issue

- Takes a passive approach/shuts down

- More likely to withdraw or give up

- Linked to feeling helpless

- Uses an emotion-focused approach

- Avoids thinking about the issue/problem

- Finds ways to lower stress/feel better

- Leads to short-term stress reduction

- Lowers confidence and self-efficacy

- Suppresses or avoids difficult emotions

7 Avoidance Coping Examples

The most obvious avoidance coping example is avoiding stressful or scary situations; however, there are many other forms of avoidant coping. These include trying to distract yourself or avoid thinking about a problem that’s stressing you out by staying busy or minimizing or denying a problem.

These include trying to distract yourself or avoid thinking about a problem that’s stressing you out by staying busy or minimizing or denying a problem.

Using drugs, alcohol, or other vices to escape reality, quiet your mind, or numb emotions can also be an unhealthy avoidance coping mechanism (i.e., escape avoidance coping).

Here are seven avoidance coping examples:

1. Situational Avoidance

Many people who struggle with anxiety disorders often avoid situations that trigger their anxiety, not realizing that this usually worsens anxiety in the long-term. Examples of situational avoidance include canceling social plans or a doctor’s appointment that you’re stressed or anxious about. Making an excuse to not go on a beach trip because you’re insecure about being in a bathing suit is another example of situational avoidance coping.

2. Denial

Denial, a common form of cognitive avoidance, is a defense mechanism where you ignore, minimize, or outright deny having a problem. Examples of denial include refusing to acknowledge there are problems within your marriage or job because you’re afraid of change or don’t want to think about any issues.

Examples of denial include refusing to acknowledge there are problems within your marriage or job because you’re afraid of change or don’t want to think about any issues.

Denial can also include normalizing a problem to reassure yourself or others. Overusing humor to make light of a problem can be another unhealthy form of avoidance coping.(FN5)

3. Procrastination

Procrastination is avoidance of a task because you see it as too difficult, overwhelming, or stressful. People who procrastinate avoid starting, working on, and completing tasks by putting them off or delaying them. Chronic procrastinators often make (and break) promises to themselves and others that they’ll do something later. Examples include pushing back a start date for a diet or waiting until the last minute to study.

4. Distraction

Another avoidance coping mechanism is to actively seek out distractions to avoid having to think about a problem. External distractions like technology or mindless activities or tasks may be go-to distractions during times of stress or discomfort. Throwing yourself into work (i.e., becoming a workaholic) or other chores can be an unhealthy distraction tactic used in avoidance coping.(FN1)(FN5)

Throwing yourself into work (i.e., becoming a workaholic) or other chores can be an unhealthy distraction tactic used in avoidance coping.(FN1)(FN5)

5. Addictions

Using drugs or alcohol to cope is a particularly destructive form of avoidance as a coping mechanism. People who drink or use substances to cope are more likely to develop addictions than those who use for social or recreational reasons.(FN8)

Examples of using substances as a form of avoidance coping include drinking to quiet your mind, de-stress after a bad day, or numb your emotions.(FN2)(FN5) This kind of avoidance can also show up as a behavioral addiction to food, sex, shopping, porn, or other online activities.

6. Venting

While venting is sometimes healthy and necessary, it can become unhealthy when it’s overused, especially when it never leads to a discussion about possible solutions.(FN3)(FN5) For example, calling a friend or coworker to complain about your job may help you feel some momentary release, but it won’t fix your problems. This is an example of an avoidance coping skill that seems normal, but can become unhealthy.(FN2)(FN5)

This is an example of an avoidance coping skill that seems normal, but can become unhealthy.(FN2)(FN5)

7. Resigned Acceptance

Resigned acceptance is a form of cognitive avoidance that some people use to cope. It involves believing that there’s nothing you can do to fix or control a stressful situation. For example, telling yourself that there’s nothing you can do or “no point” in trying to make things better. Often, these beliefs are used as an excuse to avoid taking any action to improve or change your circumstances.(FN2)(FN3)(FN5)

Options For Anxiety Treatment

Talk Therapy – Get help from a licensed therapist. Betterhelp offers online therapy starting at $60 per week. Get matched With A Therapist

Medication – Find out if anxiety medication is a good fit for you. Brightside offers a free assessment. Treatments start at $95 per month. Free Assessment

Meditation & Mindfulness – Developing mindfulness and practice can lower anxiety. Get started with Free Trial of Headspace

Get started with Free Trial of Headspace

Choosing Therapy partners with leading mental health companies and is compensated for referrals by BetterHelp, Brightside, and Headspace.

Does Avoidance Coping Work?

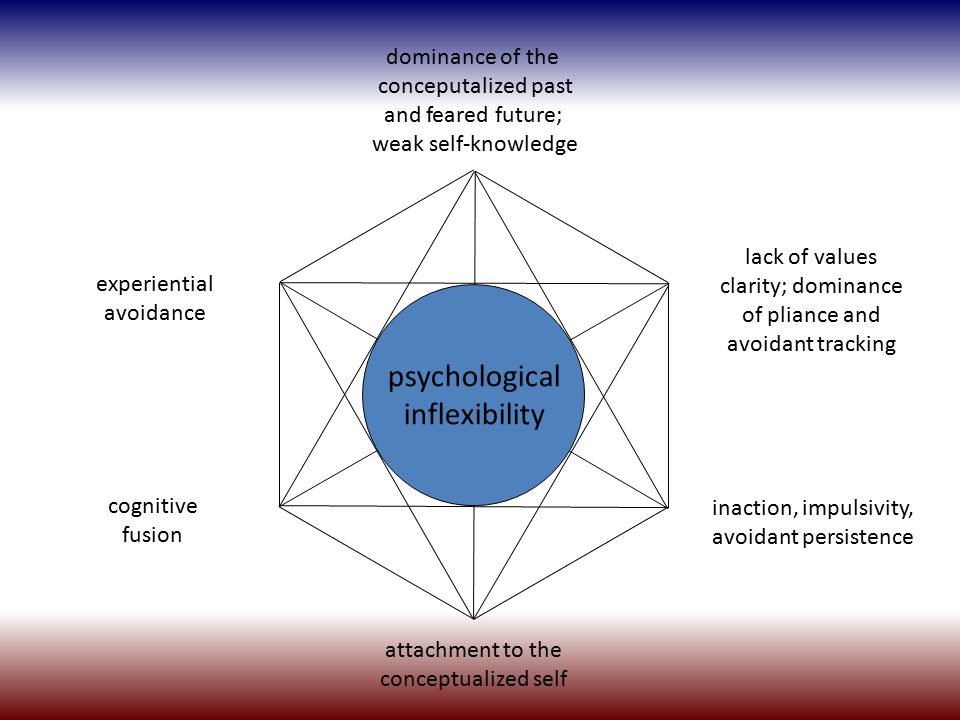

Aside from several key exceptions, avoidance coping doesn’t work because it doesn’t solve problems or address root causes of stress. Research shows that people with avoidant coping styles are more likely to be anxious, depressed, and struggle with low self-esteem.(FN3)(FN4)(FN6) They get stressed more easily and often, and are overall less happy and healthy than people with active coping styles.(FN1)(FN3)(FN4)(FN6)(FN9)

Exceptions are when avoidance coping can provide short-term benefits in certain situations. For example, if there is an actual risk or threat, avoidance is adaptive and can help to protect you from harm. Avoidance can also help you function and cope in the short-term, especially when faced with circumstances or problems that you can’t fix or control. (FN1)(FN3)

(FN1)(FN3)

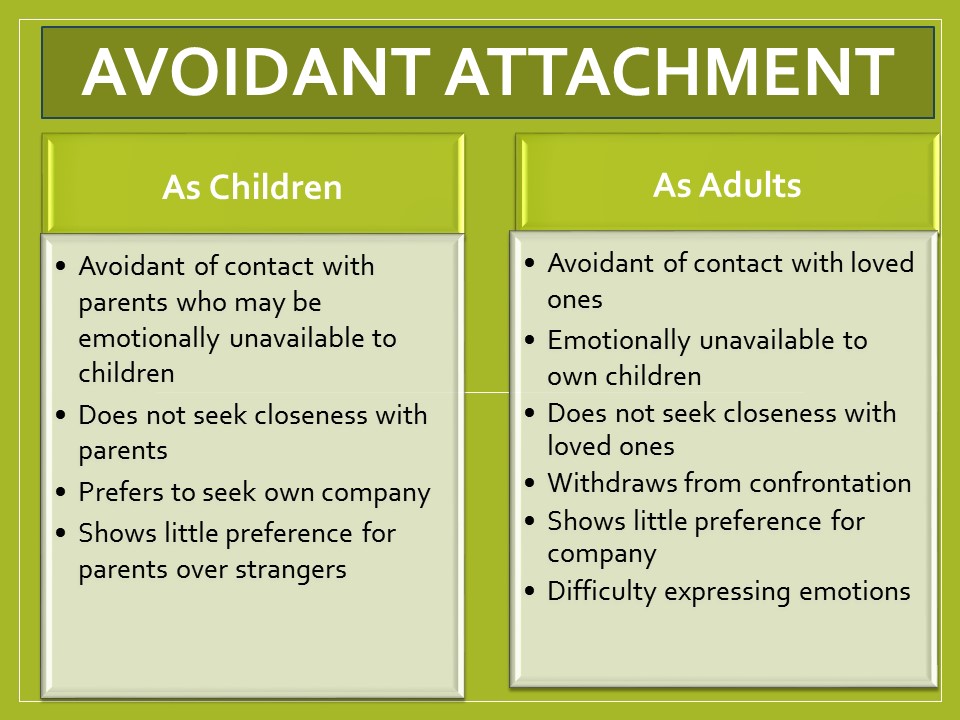

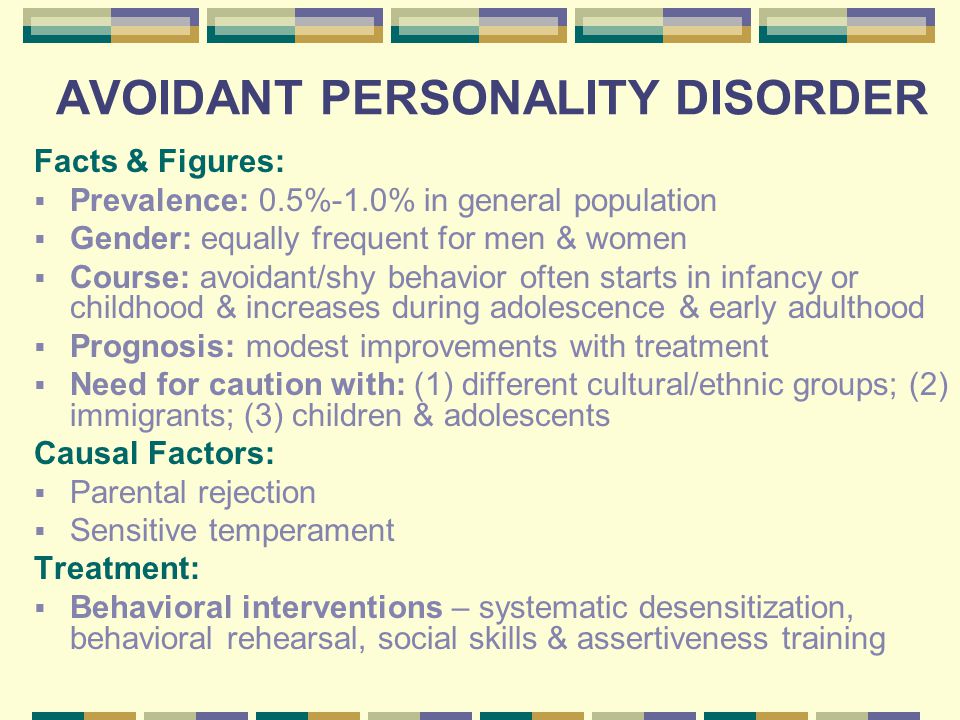

What Causes Avoidance Coping Styles?

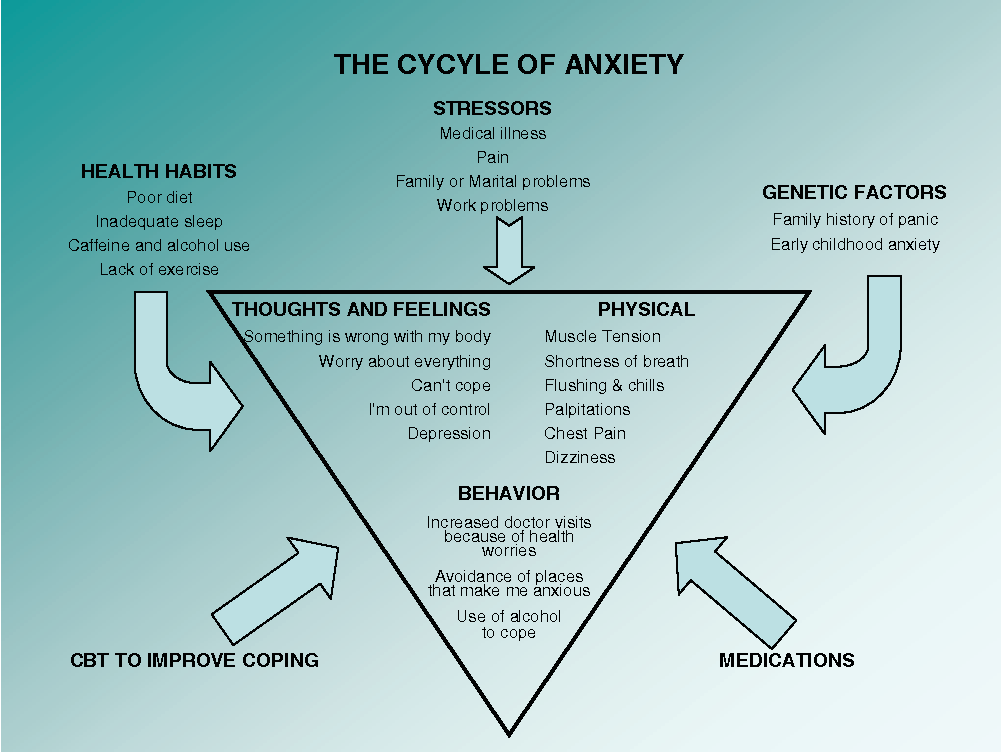

Everyone has a natural, instinctual drive to avoid situations and actions that cause pain and seek out those that cause pleasure. Still, this threat detection system can malfunction, causing false alarms to go off for falsely perceived threats. Avoidance is essentially a flight response that people use when they perceive a threat, even when it’s not one they can (or should) run from.

People with avoidant coping styles often have more sensitive threat detection systems and experience more false alarms. The more they rely on avoidance strategies, the more sensitive their threat detection systems become, causing more false alarms.

Risk factors that could cause avoidance focused coping are:(FN4)

- Having a family history or genetic disposition to anxiety or certain mental illness

- Certain personality traits or psychological make-up

- Early childhood experiences including poor parenting or trauma

- Having a chronic health or mental health disorder

- Seeing avoidant coping modeled as a child

- Having higher levels of baseline stress or anxiety symptoms

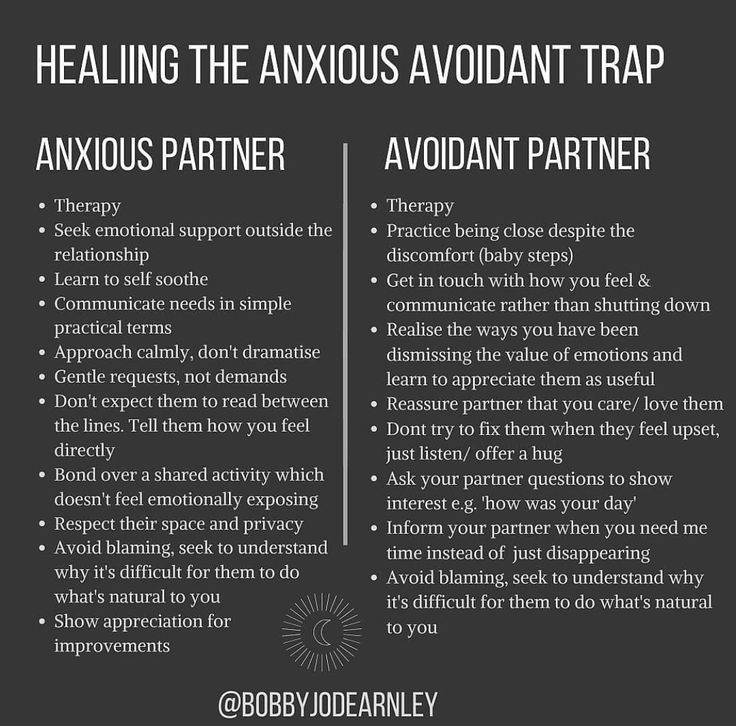

10 Tips to Stop Avoidance Coping

To stop avoidant coping and learn better ways to cope, consider seeking professional help from a therapist. That said, there are also actions you can take on your own to address avoidance.

That said, there are also actions you can take on your own to address avoidance.

Here are ten tips on how to stop avoidance coping:

1. Identify the Problem or Source of Stress

Stress, anger, anxiety, or other difficult emotions are often signals that are meant to communicate that something isn’t right. People who use healthy approach coping skills follow difficult emotions and stress to find the root cause.

When you’re stressed, consider the following:

- What is weighing the heaviest on me right now?

- Where is the majority of my stress coming from?

- What about this situation is causing me the most stress?

2. Use Your Body to

Feel Your FeelingsLearning how to experience (rather than avoid) emotions is a key step in overcoming avoidance coping.9,10 Allow yourself to fully experience and feel your feelings, even the ones you don’t like. Resist the urge to ignore them, distract yourself, or do something that will make you feel better in the moment. Instead, focus on the sensations in your body and allow yourself to feel your emotions.

Instead, focus on the sensations in your body and allow yourself to feel your emotions.

3. Focus on the Aspects of the Problem Within Your Control

You’re more likely to use avoidance coping strategies when you feel helpless and overwhelmed, which is often when you’re focusing on things you can’t control. By identifying the aspects of a problem or stressful situation that you can control, the problem may seem more manageable.9 Start by making a list of what is in your control and what’s not, and you’ll begin to manage your feelings of overwhelm.

4. Make an Action List of Ways to Improve the Situation

Taking action is a main difference between healthy coping and unhealthy avoidance coping style.1,4 For this reason, the next tip is to make an action list of things you can do to improve your situation or address the sources of your stress. While not all of these actions will guarantee the outcome you want, they can make it more likely to occur.

5. Lean On Your Support System & Ask For Help

Asking for help is a positive and healthy way to cope with stress, and is often the opposite of the withdrawal tactics used in avoidant coping.9The best way to ask for help is to consider what kind of help you need, including specific things that you can ask for (e.g., look over your resume, provide moral support, etc.)

6. Develop Healthier Lifestyle Habits & Routines

Healthy lifestyle choices are also great for your mental health. These include basic things like improving your sleep, diet, and exercise routine.9Setting goals to improve your lifestyle and develop healthier habits is a win-win and can be a great way to lower your stress.10

7. Gradually Face Your Fears

Since a lot of avoidance is driven by fear, learning to cope in healthier ways means being willing to face your fears. Make a list of things you avoid and rank each on a scale of 1-5 according to how much stress and anxiety they cause. Begin with smaller, less stressful situations and gradually work your way up to more difficult ones.

Begin with smaller, less stressful situations and gradually work your way up to more difficult ones.

These same methods are used in exposure therapy, which is one of the most effective treatments for anxiety and specific phobias.

8. Use Mindfulness & Meditation

Mindfulness and meditation can help lower stress, anxiety, and depression.10 If you’re new to these practices, try using a guided meditation or downloading a meditation app. Even doing 5-10 minutes a day can help you reduce your stress and anxiety by training your mind to focus on the present vs. getting distracted or caught up in your thoughts.

9. Think More Positive Thoughts

If you struggle with negative, worried, or self-critical thoughts, one of the best ways to begin coping in healthier ways is to work on being more positive and optimistic. Doing so can help lower your stress and improve your ability to cope.10

Here are ways to think more positively:

- List positive outcomes when you’re worried about the what-if’s

- Interrupt self-critical thoughts with self-compassion exercises

- Write down three things you feel grateful for each day in a gratitude journal

10.

Improve Your Self-care In Healthy Ways

Improve Your Self-care In Healthy WaysEating a pint of ice cream or binge watching Netflix is more likely a form of unhealthy avoidance coping vs. self-care. True self-care includes any activity or strategy that gives you something positive back. List activities that boost your mood, improve your health, or provide more mental energy or motivation, and build these into your routine. Examples include exercise, yoga, reading, hobbies, or time with friends.

Therapy For Avoidance Coping

One of the most common goals in therapy is to teach people healthier, more effective methods of coping with difficult thoughts and feelings. Therapy can also help address some of the root causes of avoidance coping, including toxic stress, anxiety, or depression.

If you or someone you care about needs help learning healthier ways to cope, you can search a free online therapist directory to find a therapist that specializes in counseling for stress reduction. You can also use search filters to see if your health insurance covers the cost of therapy.

You can also use search filters to see if your health insurance covers the cost of therapy.

Final Thoughts On Avoidant Coping

At some point in most of our lives, we will avoid stressful or difficult experiences, thoughts, and feelings; however, too much avoidance coping can backfire. Overuse is linked to higher levels of anxiety, depression, and other physical and mental illnesses.1,3,4,6,9 Active coping or approach coping skills are healthier alternatives because they help you deal with the root causes of stress, rather than just providing temporary relief.

Additional Resources

Education is just the first step on our path to improved mental health and emotional wellness. To help our readers take the next step in their journey, Choosing Therapy has partnered with leaders in mental health and wellness. Choosing Therapy may be compensated for referrals by the companies mentioned below.

BetterHelp (Online Therapy) – A therapist can teach you skills that will enable you to better cope with difficult situations. BetterHelp has over 20,000 licensed therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. BetterHelp starts at $60 per week. Complete a brief questionnaire and get matched with the right therapist for you. Get Started

BetterHelp has over 20,000 licensed therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. BetterHelp starts at $60 per week. Complete a brief questionnaire and get matched with the right therapist for you. Get Started

Online-Therapy.com – Receive help from a mental health professional. The Online-Therapy.com standard plan includes a weekly 45 minute video session, unlimited text messaging between sessions, and self-guided activities like journaling. Recently, they added Yoga videos. Get Started

Brightside Health (Online Psychiatry) – If you’re struggling with mental illness or addiction, finding the right medication can make a difference. Brightside Health treatment plans start at $95 per month. Following a free online evaluation and receiving a prescription, you can get FDA approved medications delivered to your door. Free Assessment

Headspace (Meditation App) – Headspace is the leading mindfulness and meditation app with over 70 million members. Headspace offers guidance and exercises for all skill levels, including beginners. Free Trial

Headspace offers guidance and exercises for all skill levels, including beginners. Free Trial

Choosing Therapy’s Directory – Find an experienced therapist who has your welling in mind. You can search for a therapist by specialty, availability, insurance, and affordability. Therapist profiles and introductory videos provide insight into the therapist’s personality so you find the right fit. Find a therapist today.

Choosing Therapy partners with leading mental health companies and is compensated for referrals by BetterHelp, Online-Therapy.com, Brightside, and Headspace

For Further Reading

- The University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences’ COPE inventory

- Healthy vs. Unhealthy Coping Strategies

10 sources

Choosing Therapy strives to provide our readers with mental health content that is accurate and actionable. We have high standards for what can be cited within our articles. Acceptable sources include government agencies, universities and colleges, scholarly journals, industry and professional associations, and other high-integrity sources of mental health journalism. Learn more by reviewing our full editorial policy.

Acceptable sources include government agencies, universities and colleges, scholarly journals, industry and professional associations, and other high-integrity sources of mental health journalism. Learn more by reviewing our full editorial policy.

-

Elliot, A. J., Thrash, T. M., & Murayama, K. (2011). A longitudinal analysis of self‐regulation and well‐being: Avoidance personal goals, avoidance coping, stress generation, and subjective well‐being. Journal of Personality, 79(3), 643-674. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21534967/

-

Moos, R. H., & Schaefer, J. A. (1993). Coping resources and processes: Current concepts and measures. In L. Goldberger & S. Breznitz (Eds.), Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects(pp. 234–257). Free Press.

-

Grant, D. M., Wingate, L. R., Rasmussen, K. A., Davidson, C. L., Slish, M. L., Rhoades-Kerswill, S., … & Judah, M.

R. (2013). An examination of the reciprocal relationship between avoidance coping and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(8), 878-896. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-34209-004

R. (2013). An examination of the reciprocal relationship between avoidance coping and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(8), 878-896. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-34209-004 -

Taylor, S. E., & Stanton, A. L. (2007). Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol., 3, 377-401. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17716061/

-

Litman, J. A. (2006). The COPE inventory: Dimensionality and relationships with approach-and avoidance-motives and positive and negative traits. Personality and Individual differences, 41(2), 273-284. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886906000638?via%3Dihub

-

Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H., Holahan, C. K., Brennan, P. L., & Schutte, K. K. (2005). Stress Generation, Avoidance Coping, and Depressive Symptoms: A 10-Year Model.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 658–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 658–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658 -

Roth, S., & Cohen, L. J. (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American psychologist, 41(7), 813. https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0003-066X.41.7.813

-

Creswell, K. G., Chung, T., Wright, A. G. C., Clark, D. B., Black, J. J., and Martin, C. S. ( 2015), Personality, negative affect coping, and drinking alone: a structural equation modeling approach to examine correlates of adolescent solitary drinking. Addiction, 110: 775– 783. doi: 10.1111/add.12881

-

Cassidy, T. (2000). Stress, healthiness and health behaviours: An exploration of the role of life events, daily hassles, cognitive appraisal and the coping process. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 13(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070010028679

-

American Psychological Association.

(2020, February 1). Building your resilience. http://www.apa.org/topics/resilience

(2020, February 1). Building your resilience. http://www.apa.org/topics/resilience

If you are in need of immediate medical help:

Medical

Emergency

911

Suicide Hotline

800-273-8255

Avoidance Coping | Psychology Today

When I first mention "avoidance coping," people tend to assume I just mean procrastinating, but in psychology-speak, avoidance means something a bit different.

Avoidance coping creates stress and anxiety, and ravages self-confidence. It's is a major factor that differentiates people who have common psychological problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, and/or eating disorders) vs. those who don’t.

The first step to overcoming avoidance coping is to learn to recognize it (at the time you're doing it).

Here are 9 types of avoidance coping to look out for.

1. You avoid taking actions that trigger painful memories from the past.

For example, you avoid asking questions in class because it reminds you of a time you asked a question and the teacher embarrassed you.

Or, you avoid going to a professor's office hours because she gave you a disappointing grade last semester and the thought of approaching her retriggers your feelings about the grade.

Avoiding things that trigger difficult memories is one of the most important and common types of avoidance coping.

2. You try to stay under the radar.

People who have a sense of defectiveness often try to stay “under the radar.” They often fear things like being kicked of university, or their success feels fraudulent to them. They feel like if they're noticed, their flaws will be revealed.

3. You avoid reality-testing your thoughts.

For example, you’re worried your child is on the autism spectrum but you put your head in the sand or just read stuff on the internet rather than seek a professional assessment.

4. You try to avoid the potential for people being mad at you.

For example, you avoid asking for things you want, in case the person gets mad at you for asking.

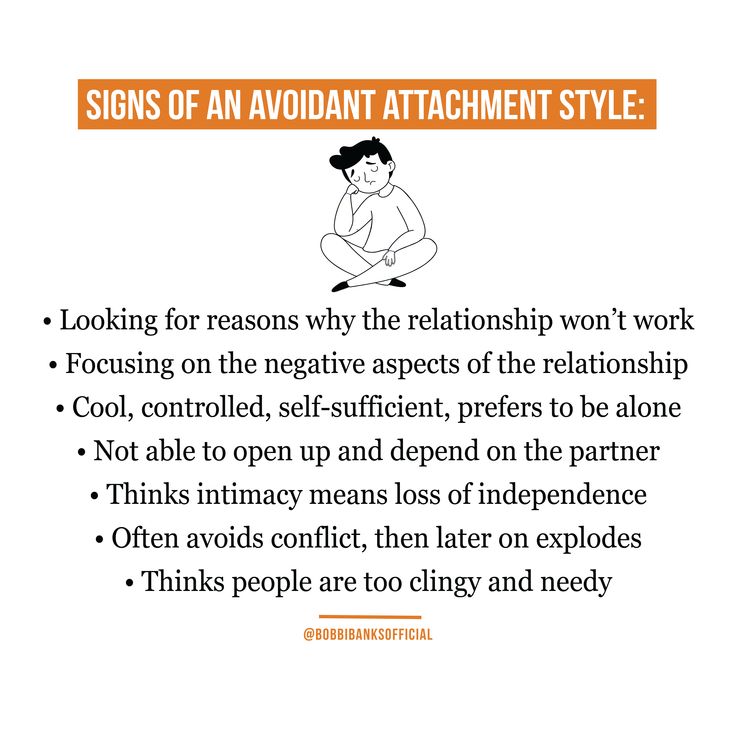

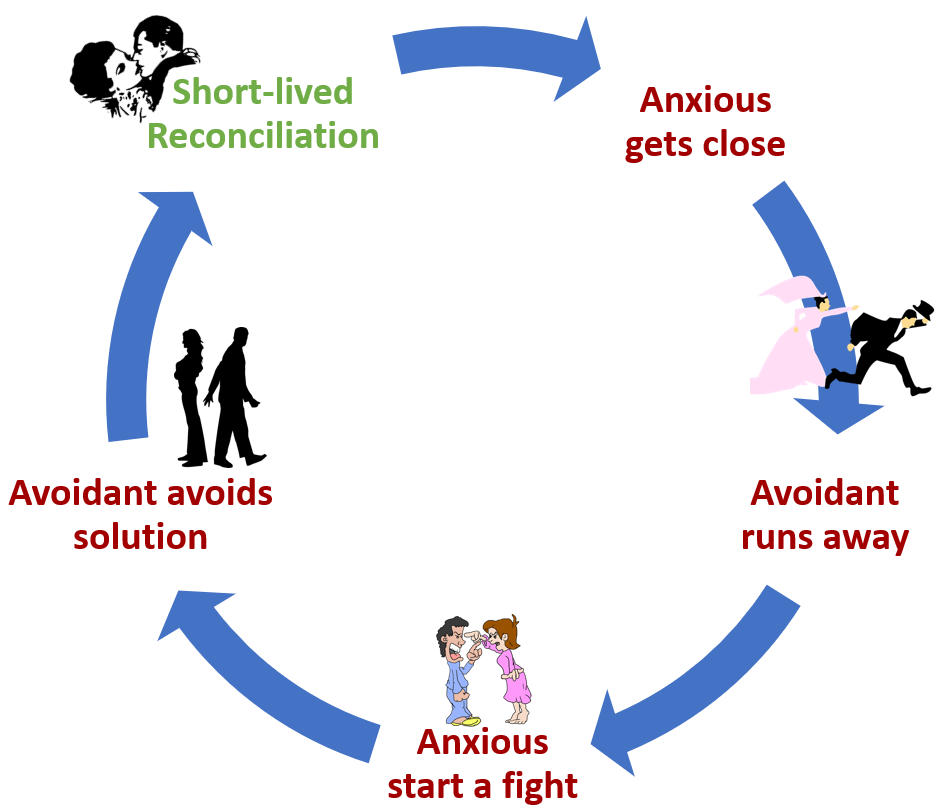

People who are very concerned about others potentially being mad at them might just be people-pleasers, or they may have anxiety about rejection. You might’ve had experiences of anger leading to rejection. or just have an anxious attachment style.

In most situations, anger doesn’t lead to rejection.

Often, trying to avoid experiencing other people being angry backfires and you end up doing things that are more likely to cause anger: e.g., you avoid telling someone you can't go to an event, squeeze it in and then end up arriving really late.

5. You have a tendency to stop working on a goal when an anxiety-provoking thought comes up.

For example, you tend to quit difficult goals or tasks if you start thinking “This is hard” or “I’m not sure if I’m going to be able to do this. ”

”

Accept that these types of thoughts are often par for the course when working on difficult goals (Also make sure you’re taking enough breaks.)

6. You avoid feeling awkward.

You avoid potentially awkward conversations not so much because you fear the consequences but because you have a tendency to avoid any feelings of awkwardness.

When you start allowing yourself to experience awkwardness, you’ll realize it’s not that bad and you can cope.

7. You avoid starting a task if you don’t know how you’re going to finish it.

Don’t worry about all the steps; just do the first logical step. Action is much more likely to produce new insights than ruminating.

8. You avoid certain physical sensations.

This is especially common in people prone to panic attacks.

Examples:

- Unfit people (and people with panic disorder) sometimes avoid sensations of exertion, e.g., getting their heart rate up during exercise.

- People with body image issues might avoid sexual sensations that activate their body image concerns.

- Overeaters sometimes avoid feeling even a little bit hungry; i.e., they eat before they feel sensations of hunger.

9. You avoid entering situations that may trigger thoughts like “I’m not the best. I’m not as good as other people.”

If your sense of self-worth is based on being better than average in all important areas, you’ll struggle with situations that trigger unfavorable social comparison.

This can really hold you back from improving in areas where you’re not strong.

Practice exposing yourself to people who are better than you in areas where you’d like to improve.

Expecting yourself to be better than average at everything, or expecting yourself to be good at things with extensive practice, is a recipe for misery!

Be sure to check out my related posts on this topic:

- Intolerance of Uncertainty

- Procrastination Tips

- The Psychology of Procrastination and Anxiety

Click here to purchase my book, The Anxiety Toolkit.

Study of passive types of coping with stress behavior as mechanisms of adaptation/disadaptation to the disease in patients with bronchial asthma

Introduction Currently, a large number of experimental facts have been accumulated that convincingly testify to the role of psychological mechanisms in the occurrence, formation and course of bronchial asthma (BA). At the same time, in the context of domestic psychological research, insufficient attention is paid to the issue of adaptation of patients with AD.

Currently, a large number of experimental facts have been accumulated that convincingly testify to the role of psychological mechanisms in the occurrence, formation and course of bronchial asthma (BA). At the same time, in the context of domestic psychological research, insufficient attention is paid to the issue of adaptation of patients with AD.

The problems of adaptation of an individual to stressful situations, in particular, to a disease, are dealt with by the direction - the psychology of coping. Coping behavior (coping) is “behavior aimed at adapting to circumstances and involving the formed ability to use certain means to overcome emotional stress” [1].

Coping behavior (coping) is “behavior aimed at adapting to circumstances and involving the formed ability to use certain means to overcome emotional stress” [1].

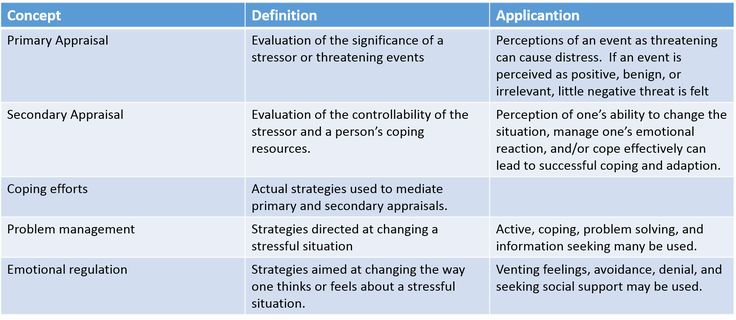

There is no single classification of coping strategies. According to Lazarus R.S., Folkman S., there are two main types of coping: problem-oriented and emotionally-oriented [2,3]. Problem-focused coping is an attempt to increase the effectiveness of interaction in the dyad "person-environment" by changing the cognitive assessment of the situation. Emotionally focused coping is thoughts and actions aimed at reducing the physical or psychological impact of stress [2,3]. A number of authors distinguish between active and passive coping strategies. Active coping - behavioral or psychological responses aimed at directly changing the nature of the stressor or rethinking. Passive (avoidant) coping can lead the individual into activities (eg drinking alcohol) or mental states (anxiety, depression) that keep them from directly addressing stressful events. Numerous studies on coping strategies show that the preference for active coping strategies, both behavioral and emotional, is the best way to deal with stressful events [4,5]. Preference for avoidance strategies is a psychological risk factor for adverse responses to stressful life events [4–7].

Numerous studies on coping strategies show that the preference for active coping strategies, both behavioral and emotional, is the best way to deal with stressful events [4,5]. Preference for avoidance strategies is a psychological risk factor for adverse responses to stressful life events [4–7].

To date, foreign researchers have accumulated extensive material on the role of coping behavior in adaptation and disadaptation to the disease in children and adults suffering from asthma in different age groups [8–20]. Most of the works are devoted to identifying the most effective - active in the fight against the disease strategies and destructive - avoiding, leading to a deterioration in health. So, Barton C. et al. It is believed that the emotionally oriented style in patients with asthma is associated with a lower perception of disease control, abuse of drug treatment, inpatient hospitalization after an asthmatic attack [8]. Nazarian D. et al. investigated the association of avoidance strategies (secondary) coping with maximum expiratory volume flow (MOF) in adults with asthma. Researchers have concluded that denial, as a form of avoidant coping, is associated with both greater asthma symptoms and worse MRV scores [12]. The results of the study of coping behavior in children with asthma are ambiguous. As noted by Mitchell D.K. and Murdock K.K., the use of both active (primary) and passive (secondary) types of coping may be associated with effective behavior management and active participation in family, social and physical activities [10]. In contrast to the above, the results of the Van De Ven M.O. et al. Adolescents with asthma aged 12 to 16 showed that patients using active types of coping, such as “overcoming a limited lifestyle”, “search for information support”, “positive reassessment”, have higher scores on the “quality of life” scale , compared with patients who prefer avoidance strategies [18].

Researchers have concluded that denial, as a form of avoidant coping, is associated with both greater asthma symptoms and worse MRV scores [12]. The results of the study of coping behavior in children with asthma are ambiguous. As noted by Mitchell D.K. and Murdock K.K., the use of both active (primary) and passive (secondary) types of coping may be associated with effective behavior management and active participation in family, social and physical activities [10]. In contrast to the above, the results of the Van De Ven M.O. et al. Adolescents with asthma aged 12 to 16 showed that patients using active types of coping, such as “overcoming a limited lifestyle”, “search for information support”, “positive reassessment”, have higher scores on the “quality of life” scale , compared with patients who prefer avoidance strategies [18].

Despite the urgency of the problem posed, the mechanisms of coping behavior in patients with asthma in domestic clinical psychology are practically not studied. A deep and high-quality study of the characteristics of coping with stressful events, in particular, the disease, of patients suffering from asthma can help in the treatment and rehabilitation of this group of patients.

A deep and high-quality study of the characteristics of coping with stressful events, in particular, the disease, of patients suffering from asthma can help in the treatment and rehabilitation of this group of patients.

The purpose of this study is to study the parameters of coping behavior in patients with AD.

Characteristics of the examined groups

and methods

The study involved 120 people aged 30 to 60 years.

The first group included 60 patients diagnosed with BA (ICD code - 10 J45.0 - J45.9), the average age was 47.2±10.2 years. The comparison group consisted of 60 conditionally healthy people without respiratory diseases, the average age was 42.8±8.7 years.

To study the frequency of use and assess the degree of effectiveness of coping strategies, the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) Lazarus, Folkman, adapted in the laboratory of the Psychoneurological Institute. V.M. Bekhterev under the direction of L.I. Wasserman.

Statistical processing of results

research

During statistical processing of the results, arithmetic mean values, standard deviations, and significance of differences between groups were calculated. The latter indicator was calculated according to the Mann-Whitney U-test. When processing the results, the computer statistical program "Statistica 6.0" was used. The MICROSOFT EXCEL 2003 program was also used. The calculation was made with a confidence level of p≤0.05.

The latter indicator was calculated according to the Mann-Whitney U-test. When processing the results, the computer statistical program "Statistica 6.0" was used. The MICROSOFT EXCEL 2003 program was also used. The calculation was made with a confidence level of p≤0.05.

Description of methodology

Description of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire method. The Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) method was developed by Lazarus and Folkman in 1988 and adapted in the laboratory of the Psychoneurological Institute. V.M. Bekhterev under the direction of L.I. Wasserman in 2009. The questionnaire includes 50 statements, each of which offers a specific behavior in a difficult situation.

The research participant is given the instruction: “You will be offered a series of statements regarding the characteristics of your behavior in difficult situations. After reading each of the statements, decide whether it is true for you or not. You can choose four answers to this question, depending on how often you use the behavior specified in the statement: 0 - "never", 1 - "rarely", 2 - "sometimes", 3 - "often". Please mark your chosen answer in the corresponding column of the questionnaire. Be careful and try to answer sincerely. There are no right or wrong (“bad” or “good”) answers here.”

Please mark your chosen answer in the corresponding column of the questionnaire. Be careful and try to answer sincerely. There are no right or wrong (“bad” or “good”) answers here.”

As follows from the instructions, the answer is assessed by the subject on a 4-point scale, depending on the frequency of using the strategy: never - 0 points, rarely - 1 point, sometimes - 2 points, often - 3 points. The points of the methodology are combined into 8 scales corresponding to coping strategies: "Confrontation", "Distancing", "Self-control", "Searching for social support", "Accepting responsibility", "Escape-avoidance", "Problem solving planning", "Positive reassessment ".

Processing and interpretation of results. The degree of preference for the strategy is determined on a scale of T-points with M (average value on the standard scale) equal to 50 T-points and σ (standard deviation) equal to 10 T-points.

To determine the "raw" indicators on the scales of the methodology, the sum of the indicators for the statements included in each of the scales is calculated, taking into account the ratio between the answer and the points awarded.

After calculating the "raw" values on the scales, they are converted into standard T-scores. To determine the standard indicator, it is necessary to correlate the "raw" score with the values of the normative group, taking into account gender and age.

The degree of preference for the subject of the strategy of coping with stress is determined on the basis of the following standards:

1. The indicator is less than 40 points - a rare use of the strategy.

2. 40 points ≤ indicator ≤ 60 points – moderate use of the appropriate strategy.

3. An indicator of more than 60 points - a pronounced preference for the appropriate strategy.

Results of study

coping behavior

and their discussion

Scale "Distance"

The mean values for patients diagnosed with BA were 53.9±9.25, for the comparison group – 46.6±9,4 (Fig. 1). Healthy subjects are significantly less likely (p=0.000) to resort to the "Distancing" strategy in comparison with BA patients. Thus, patients suffering from AD, more often than healthy subjects, resort to distancing in stressful situations. It can be assumed that the appeal to this strategy is associated with the inability to flexibly regulate interpersonal relationships, and also allows the patient with asthma to reduce the emotional degree of adherence to the disease in a stressful situation. Apparently, the preference for coping is associated with insufficient development of personal resources, psychological and physiological weakness of the body due to the disease.

Thus, patients suffering from AD, more often than healthy subjects, resort to distancing in stressful situations. It can be assumed that the appeal to this strategy is associated with the inability to flexibly regulate interpersonal relationships, and also allows the patient with asthma to reduce the emotional degree of adherence to the disease in a stressful situation. Apparently, the preference for coping is associated with insufficient development of personal resources, psychological and physiological weakness of the body due to the disease.

Flight-avoidance scale

The average values for BA patients were 57.8±8.4, which is significantly higher (p=0.000) than the values obtained in healthy subjects - 46.4±9.9 (Fig. 1). This strategy is in the first ranking position in terms of frequency of use in people with a diagnosis of bronchial asthma, i.e. is the leading one, which indicates a tendency to deny the existence of problems and avoid solving them, not to recognize a personal role in the occurrence of difficulties, deterioration of one's condition. Patients can take out their "bad" mood on others, blame relatives, bosses, colleagues for the deterioration of their health, etc. In an attempt to relieve emotional stress, patients may resort to drinking alcohol, smoking, and overeating.

Patients can take out their "bad" mood on others, blame relatives, bosses, colleagues for the deterioration of their health, etc. In an attempt to relieve emotional stress, patients may resort to drinking alcohol, smoking, and overeating.

Conclusions

1. Patients with bronchial asthma, in comparison with healthy subjects, significantly more prefer the use of passive types of coping strategies in stressful situations.

2. Patients with bronchial asthma, finding themselves in stressful situations, more often the comparison group turn to methods of detachment, switching attention, in order to reduce emotional involvement in a problem or illness, and also due to the inability to regulate interpersonal relationships.

Conclusion

The study showed that patients suffering from asthma react maladaptive in situations of illness and increased stress.

Patients with asthma to cope with stressful and problematic situations, during the period of exacerbation of the disease, often turn to avoiding coping strategies. This indicates the inability of patients to flexibly regulate interpersonal relationships, insufficient development of personal resources, psychological and physiological weakness of the body due to the disease.

This indicates the inability of patients to flexibly regulate interpersonal relationships, insufficient development of personal resources, psychological and physiological weakness of the body due to the disease.

The results obtained can be useful in creating psychoeducational programs for patients with asthma, which is a necessary component of the rehabilitation process in psychosomatic practice.

Literature

1. Malkina–Pykh I.G. Strategies for behavior under stress. [Electronic resource] // Moscow Psychological Journal. – 2005. No. 12 URL: http://magazine.mospsy.ru (date of access: 10/19/2010)

2. Folkman S. and Lazarus R.S. Coping and emotion // Monat A. and Richard S. Lazarus. stress and coping. N.-Y., 1991, 207–227

3. Lazarus Richard S. and Folkman Susan The concept of coping // Monat A. and Richard S. Lazarus. stress and coping. N.–Y., 1991, 189–206

4. Holahan, C. J., & Moos, R. H. Risk, resistance, and psychological distress: A longitudinal analysis with adults and children // Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1987, 96: 3–13.

5. Penley JA, Tomaka J, Wiebe JS The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: a meta-analytic review. // J Behav Med, 2002, 25:551–603

6. Terry DJ, Callan VJ, Sartori G Employee adjustment to an organizational merger: stress, coping and intergroup differences. // Stress Med, 1996, 12:105–122

7. Pisarski A, Bohle P, Callan VJ Effects of coping strategies, social support and work–non work conflict on shift worker’s health. // Scand J Work Env Health, 1998, 24(3):141–145

8. Barton, C, Clarke, D, Sulaiman, N, Abramson M. Coping as a mediator of psychosocial impediments to optimal management and control of asthma // Respir Med, 2003 Jul, 97:747–761

9. Hesselink, A, Penninx, B, Schlosser, M, et al The role of coping resources and coping style in quality of life of patients with asthma or COPD. // Quality Life Res, 2004, 13:509–518

10. Mitchell, D. K., & Murdock, K. K. Self–competence and coping in urban children with asthma. // Children's Health Care, 2002, 31(4): 273–293.

// Children's Health Care, 2002, 31(4): 273–293.

11. Meijer, S. A., Sinnema, G. O., Bijstra, J., Mellenbergh, G. J., & Wolters, W. H. G. Coping styles and locus of control as predictors for psychological adjustment of adolescents with a chronic illness. // Social Science & Medicine, 2002, 54(9): 1453–1461.

12. Nazarian, D., Smyth, J. M., & Sliwinski, M. J. A naturalistic study of ambulatory asthma severity and reported avoidant coping styles. // Chronic Illness, 2006, 2(1): 51–58.

13. Lima L, Guerra MP, de Lemos MS. The psychological adjustment of children with asthma: study of associated variables // Span J Psychol. May 2010; 13(1):353–63.

14. Kim DH, Yoo IY. Development of a questionnaire to measure resilience in children with chronic diseases // J Korean Acad Nurs. 2010 Apr; 40(2):236–46.

15. Kaptein AA, Klok T, Moss-Morris R, Brand PL. Illness perceptions: impact on self-management and control in asthma // Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. Jun 2010; 10(3):194–199.

16. Van De Ven MO, Engels RC, Sawyer SM, Otten R, Van Den Eijnden RJ. The role of coping strategies in quality of life of adolescents with asthma. // Qual Life Res. May 2007; 16(4): 625–34.

17. Rydstrom I, Hartman J, Segesten K. Not letting the disease get the upper hand over life: strategies of teens with asthma. // Scand J Caring Sci. 2005 Dec;19(4): 388–95.

18. Fley G, Beier J. Coping strategies of children with asthma. Testing the applicability of the German version of the Schoolagers' Coping Strategies Inventory (SCSI). //Pflege. February 2006; 19(1):4–10.

19. Murdock KK, Greene C, Adams SK, Hartmann W, Bittinger S, Will K. The puzzle of problem–solving efficacy: understanding anxiety among urban children coping with asthma–related and life stress. // Anxiety Stress Coping. 2010 Jun; 23(4):383–98.

20. Protudjer JL, Kozyrskyj AL, Becker AB, Marchessault G. Normalization strategies of children with asthma. // Qual Health Res. 2009Jan; 19(1):94–104.

Types of coping — Knife

Discovery of stress

The term “stress” was first introduced by the American physiologist Walter Cannon in 1926. However, the Canadian biologist Hans Selye developed the theory and explained its mechanisms.

In Selye's concept, stress is understood as any reaction in the body under the influence of the current situation. Stress acts as a signal of the need for urgent change. This is a useful state that helps us adapt to the environment. In contrast to "stress" Selye singled out the concept "distress" . It occurs when the body's resources are insufficient for changes. Distress is the last stage of stress, followed by the death of the organism.

Stress does not harm the body, but, on the contrary, contributes to survival in the changing conditions of the surrounding world.

Selye's theory became a classic in the scientific world, and subsequent researchers started from it. His main merit was that he was the first to consider the reaction of the body as one of the factors in the negative effects of stress. What matters is not the conditions in which we find ourselves, but how we react to them and cope with them. The mechanism that helps a person cope with threatening stimuli and avoid their negative influence is called coping .

His main merit was that he was the first to consider the reaction of the body as one of the factors in the negative effects of stress. What matters is not the conditions in which we find ourselves, but how we react to them and cope with them. The mechanism that helps a person cope with threatening stimuli and avoid their negative influence is called coping .

How do we deal with stress? Three points of view on coping

Coping is a person's conscious overcoming of negative and painful feelings during periods of stress, which allows maintaining emotional well-being. The term, borrowed from English, literally means "coping" with stress. The choice of means to overcome negative emotions is extensive. Someone resorts to physical exercises, another needs the support of loved ones. Both options refer to coping, as they help a person relieve excess stress.

Today there are three approaches to coping behavior: dispositional, situational and integrative.

Let's start with dispositional approach . It is based on the fact that a person as a whole is stable and unchanging. He has a set of traits, world views and habits (dispositions) that determine the trajectory of behavior when faced with difficulties. Our dispositions are hardwired into the very structure of personality and cannot be changed. Since we ourselves do not change, our behavior to overcome stress remains unchanged. Therefore, representatives of this approach emphasize the uniformity and individuality of the methods of coping with difficulties.

The dispositional approach identifies coping styles based on the Big Five questionnaire, which collects five defining personality traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, conscientiousness, conscientiousness. The way a person copes with stress depends on the leading trait in a person:

- Neuroticism is associated with an ineffective response style, for example, self-blame and passivity.

- Extraversion is associated with external response to stress, expression of emotions, discussion of problems with friends or acquaintances.

- Openness to new experiences allows a person to cope with difficulties and solve problems through an active search for information and ways to move forward.

- Conscientiousness is associated with perseverance in overcoming difficulties and a lower risk of resorting to psychoactive substances when stressed.

- Kindness refers to careful planning for solving problems and often turning to others for help.

For the dispositional approach, personality characteristics determine our interaction with the stressor. Within its framework, a person is a system frozen in time.

This point of view is contrasted with the situational approach . It appeared at a time when scientists moved from a behavioral model to a more humanistic one. Behaviorists viewed humans as a set of learned responses to their environment. At that time, there was still no MRI or encephalograph to fix the trace of mental processes. Therefore, the subject of study of behaviorists was human behavior. However, behaviorism has not provided exhaustive answers to all questions about human behavior.

Behaviorists viewed humans as a set of learned responses to their environment. At that time, there was still no MRI or encephalograph to fix the trace of mental processes. Therefore, the subject of study of behaviorists was human behavior. However, behaviorism has not provided exhaustive answers to all questions about human behavior.

In the second half of the 20th century, the focus shifted to the study of mental processes. Scientists have devices for their fixation and analysis. The focus was on a person who actively interacts and transforms the world around him, and not only responds with learned reactions to stimuli.

One of the theories of that time was the Lazarus stress model, which he called "transactional". In it, the individual gains freedom in choosing the means of coping with difficulties. It ceases to be dependent on its dispositions and is capable of continuous change. A person is considered inseparably from the situation in which he is - as a word, the meaning of which we cannot accurately understand out of context.

For Lazarus, the personality is in constant relationship with the environment, which makes its demands on us. Such requirements include the conditions for entering an educational institution or promotion at work, the search for suitable housing. Stress, which is the result of the relationship between the demands placed on a person and his resources, occurs when the demands exceed our capabilities. Coping with stress is considered in the dynamics of interaction between a person and the environment. With the help of various strategies, a person rebuilds this interaction, trying to minimize the expected damage.

In Lazarus theory, the decision about which form of coping to choose in the present conditions is formed on the basis of an assessment of the current situation. Evaluation is cyclical until an effective coping strategy is found.

The evaluation process includes three successive steps. For example, there is a reduction in the workplace. In order not to fall under it, we need to fulfill the plan by 100%, but it is better to overfulfill it.

- Initial estimate : what harm will we get if we lose our job? This is the loss of wages, resulting in a lack of funds to ensure life. The situation is potentially threatening. In this case, we move on to the secondary assessment. There may be another scenario: the salary does not matter to us, since we can easily live on passive income. Then the situation is not perceived as stressful, and the person stops at the first phase.

- Secondary evaluation : what can be done to avoid potential harm, i.e. dismissal? Should you work better, try to please your boss, or interfere with colleagues so that they are kicked out? When a decision is made, the situation is reassessed.

- Reassessment : Accept feedback on the current state of affairs and adjust the assessment based on new information. What happened after we started to act? Are we still in danger or have we managed to avoid a negative outcome? Is there anything else that needs to be done?

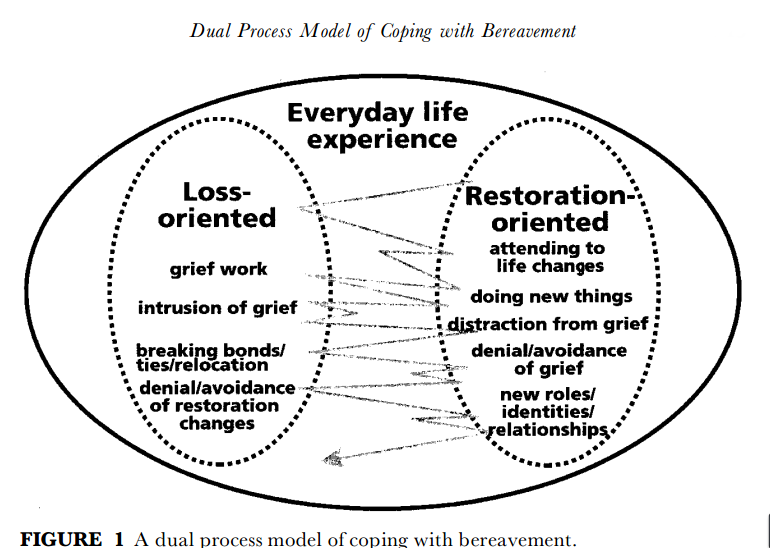

After the assessment is made, the implementation of coping behavior begins. Lazarus distinguishes between two types of coping strategies. The first one, "focusing on the problem" , is aimed at managing the situation. In this case, a person believes that the situation can be changed, and his strategy is aimed at transforming external conditions. For example, we are late for an important meeting. Instead of a long metro ride, you can call a taxi and get there faster. We transform external circumstances depending on the requirements, ensuring a further comfortable life. However, we do not always find ourselves in situations that we can control.

Lazarus distinguishes between two types of coping strategies. The first one, "focusing on the problem" , is aimed at managing the situation. In this case, a person believes that the situation can be changed, and his strategy is aimed at transforming external conditions. For example, we are late for an important meeting. Instead of a long metro ride, you can call a taxi and get there faster. We transform external circumstances depending on the requirements, ensuring a further comfortable life. However, we do not always find ourselves in situations that we can control.

The second type of coping strategies is “focusing on emotions” . It is used when we cannot change the situation and we can only change something in ourselves in order to cope with it. For example, we missed the plane and cannot call the pilot and say "turn back, I'll go on board now." In our power is only the perception of what is happening, our own emotions and reactions. We will probably get angry and upset, start cursing and swearing. In this case, our task is to put emotions in order, give them an outlet, feel better emotionally. Emotion-focused coping strategies include exercise, shopping, humor.

In this case, our task is to put emotions in order, give them an outlet, feel better emotionally. Emotion-focused coping strategies include exercise, shopping, humor.

After we feel better, and emotions no longer interfere with making informed decisions, we can move on to the first type of coping strategies. For example, refund money for a ticket or find another flight.

It should be noted that all these processes are extended in time and can last from several minutes (with a weak stressor) to several years (with a strong stressor). Coping strategies can be intertwined and used together.

Combinations of types of coping strategies can be traced to the stages of grief at loss described by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross:

- Negative . Unwillingness to accept the situation, an attempt to protect one's psyche from unexpected circumstances. There is a primary assessment of the situation - how dangerous is it for us?

- Anger, resentment .

Applying emotion-focused coping strategies. Actions are aimed at improving your mental well-being and getting rid of negative feelings.

Applying emotion-focused coping strategies. Actions are aimed at improving your mental well-being and getting rid of negative feelings. - Trade or deal . Applying problem-focused coping strategies. Attempts to influence the situation.

- Depression and loss . Emotion-focused coping strategies again. Reassessment of the situation.

- Acceptance and humility . Emotions subside, allowing rationality to move on. The restructuring of social ties, strategies are aimed at changing the situation.

Each person can go through the stages given in his own way, some of them may be absent or change their order. For example, when a long and valuable relationship is broken, shock and disappointment may initially follow. After that, tears or undirected activity will come, a desire to be distracted with the help of alcohol. Then, attempts are possible to return the person, to maintain communication with him. A state of depression may occur, a need to move away from the familiar environment. Then the person will begin an active restructuring of social relations. At each stage, there is a reassessment of resources and the state of affairs. In the event of a break in relations, the situation is weakly amenable to change. Therefore, it remains for us to change our attitude towards what happened, work with our emotions and undergo all kinds of transformations until we feel that we have coped with the loss.

A state of depression may occur, a need to move away from the familiar environment. Then the person will begin an active restructuring of social relations. At each stage, there is a reassessment of resources and the state of affairs. In the event of a break in relations, the situation is weakly amenable to change. Therefore, it remains for us to change our attitude towards what happened, work with our emotions and undergo all kinds of transformations until we feel that we have coped with the loss.

Finally, the integrative approach combines dispositional and situational variables. In it, the choice of coping behavior in each case is influenced by several factors. These include both personal characteristics and circumstances that change from case to case. It is impossible to separate the variables affecting a person from each other - we can only trace their interaction.

The integrative approach includes such scholars as Carver, Scheir, and Wentraub. They are famous for creating Stress Coping Questionnaire (COPE-inventory). These researchers recognized the separation of coping strategies (focused on either emotion or problem). However, they considered it insufficient to describe human actions in a stressful situation and identified 13 aspects of overcoming difficulties. Five of them are problem-focused, the other five are emotion-focused. The remaining three are classified as "less effective" strategies (over-focus on emotions, behavioral and mental detachment). After that, two more scales were added: humor and alcohol.

These researchers recognized the separation of coping strategies (focused on either emotion or problem). However, they considered it insufficient to describe human actions in a stressful situation and identified 13 aspects of overcoming difficulties. Five of them are problem-focused, the other five are emotion-focused. The remaining three are classified as "less effective" strategies (over-focus on emotions, behavioral and mental detachment). After that, two more scales were added: humor and alcohol.

Why is sleep also coping?

A more biological approach to dealing with stress and coping with it is outlined in the book by V.V. Arshavsky and V.S. Rotenberg "Search activity and adaptation". Domestic physiologists are changing the old views on the problem of stress. For example, they doubt the correctness of the thesis about the dangers of negative emotions. The authors give an example of a situation where a person was on the verge of death, but was not exposed to the harmful effects of stress and did not get sick. A similar question was asked by Viktor Frankl, a psychologist who survived the concentration camp. He explained the survival of people in extreme conditions by the presence of a sense in them in order to live. Arshavsky and Rotenberg also give an answer to this question, but in terms of physiology: for them, the main reason for overcoming stressful conditions is the search activity of a person. It is aimed at interacting with the environment to change the situation or attitude towards it.

A similar question was asked by Viktor Frankl, a psychologist who survived the concentration camp. He explained the survival of people in extreme conditions by the presence of a sense in them in order to live. Arshavsky and Rotenberg also give an answer to this question, but in terms of physiology: for them, the main reason for overcoming stressful conditions is the search activity of a person. It is aimed at interacting with the environment to change the situation or attitude towards it.

Scientists considered creativity to be the highest manifestation of search behavior. Through creative activity, a person can search for new information, transform the external and internal sides of the problem.

Within the framework of the theory of search activity, it does not matter what emotions we experience - positive or negative. What matters is how we respond to them. A similar point of view was met before, but Arshavsky and Rotenberg showed this at the level of physiology. The researchers emphasize that increased motor activity does not count as search activity. These behaviors may be non-directional and may not help the person cope with stress. Automatic involuntary actions are not considered search activity either.

The researchers emphasize that increased motor activity does not count as search activity. These behaviors may be non-directional and may not help the person cope with stress. Automatic involuntary actions are not considered search activity either.

If human behavior cannot be an unambiguous criterion for search activity, can we fix it objectively? Such a visual indicator is the hippocampal theta rhythm (4–8 Hz), which manifests itself during the processes of attention, memorization and information processing. Its presence indicates search activity.

Refusal to seek is manifested in two forms: frustration and passive-defensive behavior . In the first case, a person loses interest in life and new achievements. His actions are aimed at maintaining his old routine, in which there is no place for search and development. In the second case, behavior is characterized by avoidance of problems, avoidance. In both cases, a person ceases to express and realize himself in external life, which leads to a weakening of the body during periods of stress. Refusal to search worsens our moral and physical condition, therefore, nature provides protection from it in the form of paradoxical sleep.

Refusal to search worsens our moral and physical condition, therefore, nature provides protection from it in the form of paradoxical sleep.

Our sleep is divided into 2 phases: slow and fast (aka paradoxical). REM sleep differs from slow sleep in that during it the brain behaves in the same way as in the waking state. Increased brain activity is expressed in rapid eye movement and dreams. Over the entire night, on average, 4-5 phases of REM sleep occur, providing 4-5 dreams per night.

When we dream, we start the process of searching activity. If in wakefulness there was a refusal to search, then in a dream the body compensates for this state.

Solving a problem in the real world turns into a dream. Search activity is expressed in dreams. In them, we can run away from the monster, build cities and perform absolutely any action that we cannot bring to life. The proof of the manifestation of search activity is the hippocampal theta rhythm during REM sleep.