Adhd and quitting smoking

Four Things People with ADHD Should Know About Smoking

1. Smoking is twice as common among people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than in the general population, and fewer ADHD smokers succeed in quitting.WHY SMOKING IS COMMON AMONG PEOPLE WITH ADHD

“An appealing short-term effect of nicotine is that it helps with the ability to focus. This is conceivably one reason why many people with ADHD smoke,” says Lirio Covey, PhD, professor of clinical psychology in Columbia’s Department of Psychiatry. Dr. Covey, former director of the Smoking Cessation Clinic at Columbia University Medical Center, currently investigates the effect of smoking on people with ADHD and the best techniques to help them quit.

“People with ADHD also think that smoking cigarettes calms them down,” she adds, “but lab studies have shown that smoking can aggravate hyperactivity.”

2. An ADHD drug, methylphenidate (Concerta), may help some ADHD smokers quit.ADVICE FOR ADHD SMOKERS TRYING TO QUIT

Whether methylphenidate can help depends on the type of ADHD symptoms patients experience, Dr. Covey says. Between 2005 and 2008, Dr. Covey and her research group tested the idea that treatment with methylphenidate, by reducing the symptoms of ADHD, would improve the success of a smoking cessation treatment (behavioral counseling paired with the nicotine patch).

“The study found that methylphenidate reduced ADHD symptoms, but it did not improve the overall quit rate,” she says.

But when Dr. Covey analyzed the results more closely, she found that certain groups seemed to benefit from methylphenidate. “Smokers with more severe ADHD symptoms did better with methylphenidate than smokers with less intense symptoms, and those who primarily had attention problems did better than those with hyperactivity problems. Another surprising finding that merits further study was that members of minority groups did better with methylphenidate compared to placebo.”

3. Quitting will not make you more anxious or depressed.“A lot of people think smoking reduces anxiety. When smokers are under stress, the first thing they do is smoke a cigarette,” Dr. Covey says. “This is one reason people are afraid to even attempt quitting. And some older research did suggest depression could be a side effect of quitting.”

The newest research shows that, for most people, mood improves or remains unchanged. In Dr. Covey’s latest study, published this summer in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, signs of anxiety and depression were tracked in 110 smokers with ADHD who succeeded in quitting and 145 who were unable to quit.

will_quitting_increase_anxiety_or_depression

“We found that anxiety declined in all the participants, but the decline was greater in successful quitters. It happened right away, one week after quit day, and it lasted until the end of the trial,” she says.

Symptoms of depression initially declined more in the quitters, but by the end of the trial, both groups experienced fewer symptoms of depression. “To me, that says a lot about the benefits of participating in a clinical trial,” Dr. Covey says, “but the bottom line is that most smokers with ADHD can stop smoking and not experience any worsening of mood.”

Yet Dr. Covey warns that some people may indeed experience these negative effects, and clinicians need to watch out for them.

“I’ve had patients who became depressed after quitting,” Dr. Covey says. “They had depression earlier and that reemerged after quitting. So some smokers need additional treatment.”

4. People with ADHD can quit, but it may take several attempts.

In Dr. Covey’s study, 43 percent successfully quit using a combination of behavioral counseling and the nicotine patch (in most clinical trials of smoking cessation treatments, 20 percent to 30 percent of participants quit).

MULTIPLE ATTEMPTS OFTEN NEEDED TO QUIT SMOKING

The newer nicotine nasal spray is also very helpful for smokers with ADHD in reducing craving and withdrawal symptoms. “The patch can take longer to have an effect because the nicotine has to go through the skin. The nasal spray is very fast, though not as fast as a cigarette,” Dr. Covey says. “But it’s still nicotine—an addictive drug—so I make sure they reduce the frequency of use over time.”

The nasal spray is very fast, though not as fast as a cigarette,” Dr. Covey says. “But it’s still nicotine—an addictive drug—so I make sure they reduce the frequency of use over time.”

Dr. Covey encourages smokers to try again if the first (or second, or third) attempt fails. “The thinking is that for most people, it takes several attempts before you finally succeed. People learn at each attempt what doesn’t work,” Dr. Covey says.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SN_d9RBvt9Q

The ADHD/Smoking trial was conducted by the Clinical Trials Network of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This study was funded by NIH grants K24DA022412, U10DA013035, and U10DA013732.

Read this post in Spanish here.

ADHD and Smoking - PMC

1. Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet. 2003;362:847–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. CDC. Annual smoking attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs— United States, 1995–1999. MMWR. 2002;51:300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MMWR. 2002;51:300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Grant BF, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61:1107–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Lasser K, et al. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Breslau N. Psychiatric comorbidity of smoking and nicotine dependence. Behav. Genet. 1995;25:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. John U, et al. Smoking, nicotine dependence and psychiatric comorbidity—a population-based study including smoking cessation after three years. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Pomerleau OF, et al. Cigarette smoking in adult patients diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Subst. Abuse. 1995;7:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Kollins SH, et al. Association between smoking and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in a population-based sample of young adults. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:1142–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:1142–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (text rev) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

10. Kessler RC, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:716–723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Polanczyk G, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:942–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Pelham WE, et al. The economic impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Ambul. Pediatr. 2007;7:121–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Rasmussen ER, et al. Comparison of male adolescent-report of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms across two cultures using latent class and principal components analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2002;43:797–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2002;43:797–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Tercyak KP, et al. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms with levels of cigarette smoking in a community sample of adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2002;41:799–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Shiffman S. Tobacco “chippers”—individual differences in tobacco dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1989;97:539–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Donny EC, Dierker LC. The absence of DSM-IV nicotine dependence in moderate-to-heavy daily smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:93–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. CDC. Cigarette Smoking Among Adults— United States, 2000. MMWR. 2002;51:642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Tucker JS, et al. Predictors of the transition to regular smoking during adolescence and young adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health. 2003;32:314–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Gilpin EA, et al. How many adolescents start smoking each day in the United States? J. Adolesc. Health. 1999;25:248–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Adolesc. Health. 1999;25:248–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Gritz ER, et al. The tobacco withdrawal syndrome in unaided quitters. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86:57–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Hughes JR, et al. Smoking cessation among self-quitters. Health Psychol. 1992;11:331–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults— United States, 2006. MMWR. 2007;56:1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Croghan GA, et al. Comparison of nicotine patch alone versus nicotine nasal spray alone versus a combination for treating smokers: A minimal intervention, randomized multicenter trial in a nonspecialized setting. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2003;5:181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Lerman C, et al. Individualizing nicotine replacement therapy for the treatment of tobacco dependence: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004;140:426–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Nides M, et al. Smoking cessation with varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: Results from a 7-week, randomized, placebo- and bupropion-controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1561–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1561–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Milberger S, et al. ADHD is associated with early initiation of cigarette smoking in children and adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1997;36:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Lambert NM, Hartsough CS. Prospective study of tobacco smoking and substance dependencies among samples of ADHD and non-ADHD participants. J. Learn Disabil. 1998;31:533–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Molina BS, Pelham WE., Jr Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003;112:497–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Barkley RA, et al. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: I. An 8-year prospective follow-up study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1990;29:546–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Biederman J, et al. Is ADHD a risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorders? Findings from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1997;36:21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1997;36:21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Boyle MH, Offord DR. Psychiatric disorder and substance use in adolescence. Can. J. Psychiatry. 1991;36:699–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Milberger S, et al. Associations between ADHD and psychoactive substance use disorders. Findings from a longitudinal study of high-risk siblings of ADHD children. Am. J. Addict. 1997;6:318–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Aytaclar S, et al. Association between hyperactivity and executive cognitive functioning in childhood and substance use in early adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1999;38:172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Burke JD, et al. Which aspects of ADHD are associated with tobacco use in early adolescence? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2001;42:493–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Whalen CK, et al. The ADHD spectrum and everyday life: Experience sampling of adolescent moods, activities, smoking, and drinking. Child Dev. 2002;73:209–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Child Dev. 2002;73:209–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Pomerleau CS, et al. Smoking patterns and abstinence effects in smokers with no ADHD, childhood ADHD, and adult ADHD symptomatology. Addict. Behav. 2003;28:1149–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Rohde P, et al. Psychiatric disorders, familial factors, and cigarette smoking: II. Associations with progression to daily smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:119–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Fuemmeler BF, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms predict nicotine dependence and progression to regular smoking from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007;32:1203–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. McClernon FJ, et al. Effects of smoking abstinence on adult smokers with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Results of a preliminary study. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2008;46:289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Humfleet GL, et al. Preliminary evidence of the association between the history of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and smoking treatment failure. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2005;7:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nicotine Tob. Res. 2005;7:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Xian H, et al. The heritability of failed smoking cessation and nicotine withdrawal in twins who smoked and attempted to quit. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2003;5:245–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Faraone SV, et al. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:1313–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Li MD, et al. A meta-analysis of estimated genetic and environmental effects on smoking behavior in male and female adult twins. Addiction. 2003;98:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Li MD, et al. Progress in searchingfor susceptibility loci and genes for smoking-related behaviour. Clin. Genet. 2004;66:382–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Maher BS, et al. Dopamine system genes and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A metaanalysis. Psychiatr. Genet. 2002;12:207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Munafo M, et al. The genetic basis for smoking behavior: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:583–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:583–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Todd RD, et al. Collaborative analysis of DRD4 and DAT genotypes in population-defined ADHD subtypes. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2005;46:1067–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. McGough JJ. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder pharmacogenomics. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:1367–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Hamarman S, et al. Dopamine receptor 4 (DRD4) 7-repeat allele predicts methylphenidate dose response in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A pharmacogenetic study. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2004;14:564–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Joober R, et al. Dopamine transporter 3′UTR VNTR genotype and ADHD: A pharmacobehavioural genetic study with methylphenidate. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1370–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Stein MA, et al. Dopamine transporter genotype and methylphenidate dose response in children with ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1374–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2005;30:1374–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. McGough J, et al. Pharmacogenetics of methylphenidate response in preschoolers with ADHD. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2006;45:1314–1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Albayrak O, et al. Genetic aspects in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Neural. Transm. 2008;115:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Arcos-Burgos M, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a population isolate: Linkage to loci at 4q13.2, 5q33.3, 11q22, and 17p11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:998–1014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Bakker SC, et al. A whole-genome scan in 164 Dutch sib pairs with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Suggestive evidence for linkage on chromosomes 7p and 15q. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:1251–1260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Ogdie MN, et al. A genomewide scan for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in an extended sample: Suggestive linkage on 17p11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:1268–1279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:1268–1279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Ogdie MN, et al. Pooled genome-wide linkage data on 424 ADHD ASPs suggests genetic heterogeneity and a common risk locus at 5p13. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Hebebrand J, et al. A genome-wide scan for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 155 German sib-pairs. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:196–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Manolio TA, et al. New models of collaboration in genome-wide association studies: The Genetic Association Information Network. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1045–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Gerra G, et al. Association of the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism with smoking behavior among adolescents. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B: Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2005;135:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Hutchison KE, et al. The DRD4 VNTR polymorphism influences reactivity to smoking cues. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2002;111:134–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Ishikawa H, et al. Association between serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and smoking among Japanese males. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:831–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Lerer E, et al. Why do young women smoke? II. Role of traumatic life experience, psychological characteristics and serotonergic genes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:771–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Lerman C, et al. Depression and self-medication with nicotine: The modifying influence of the dopamine D4 receptor gene. Health Psychol. 1998;17:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Luciano M, et al. Effects of dopamine receptor D4 variation on alcohol and tobacco use and on novelty seeking: Multivariate linkage and association analysis. Am. J. Med. Genet. B: Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2004;124:113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Skowronek MH, et al. Interaction between the dopamine D4 receptor and the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphisms in alcohol and tobacco use among 15-year-olds. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neurogenetics. 2006;7:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Timberlake DS, et al. An association between the DAT1 polymorphism and smoking behavior in young adults from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Health Psychol. 2006;25:190–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Tapper AR, et al. Nicotine activation of alpha4* receptors: sufficient for reward, tolerance, and sensitization. Science. 2004;306:1029–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Sullivan PF, et al. An association study of DRD5 with smoking initiation and progression to nicotine dependence. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;105:259–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. McClernon FJ, et al. DRD4 VNTR polymorphism is associated with transient fMRI-BOLD responses to smoking cues. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2007;194:433–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Greenbaum L, et al. Why do young women smoke? I. Direct and interactive effects of environment, psychological characteristics and nicotinic cholinergic receptor genes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:312–322. 223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:312–322. 223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Hutchison KE, et al. CHRNA4 and tobacco dependence: From gene regulation to treatment outcome. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;64:1078–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Li MD, et al. Ethnic- and gender-specific association of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha4 subunit gene (CHRNA4) with nicotine dependence. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:1211–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Ehringer MA, et al. Association of the neuronal nicotinic receptor beta2 subunit gene (CHRNB2) with subjective responses to alcohol and nicotine. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007;144:596–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Li MD. Identifying susceptibility loci for nicotine dependence: 2008 update based on recent genome-wide linkage analyses. Hum. Genet. 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Lerman CE, et al. Genetics and smoking cessation improving outcomes in smokers at risk. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007;33:S398–S405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Yudkin P, et al. Effectiveness of nicotine patches in relation to genotype in women versus men: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328:989–990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. David SP, et al. Pharmacogenetic clinical trial of sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2007;9:821–833. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. McClernon FJ, et al. Interactions between genotype and retrospective ADHD symptoms predict lifetime smoking risk in a sample of young adults. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2008;10:117–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Neuman RJ, et al. Prenatal smoking exposure and dopaminergic genotypes interact to cause a severe ADHD subtype. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;61:1320–1328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Todd RD, Neuman RJ. Gene–environment interactions in the development of combined type ADHD: Evidence for a synapse-based model. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007;144:971–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Genet. 2007;144:971–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Todd RD, et al. Mutational analysis of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 subunit gene in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Evidence for association of an intronic polymorphism with attention problems. Mol. Psychiatry. 2003;8:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Kent L, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha4 subunit gene polymorphism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr. Genet. 2001;11:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Brookes K, et al. The analysis of 51 genes in DSM-IV combined type attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Association signals in DRD4, DAT1 and 16 other genes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:934–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Guan L, et al. A high-density singlenucleotide polymorphism screen of 23 candidate genes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Suggesting multiple susceptibility genes among Chinese Han population. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Lee J, et al. Association study of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha4 subunit gene, CHRNA4, in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Kent L, et al. No association between CHRNA7 microsatellite markers and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;105:686–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Voineskos S, et al. Association of alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor and heavy smoking in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:412–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Grace AA. Psychostimulant actions on dopamine and limbic system function: Relevance to the pathophysiology and treatment of ADHD. In: Solanto MV, Arnsten AFT, Castellanos FX, editors. Stimulant Drugs and ADHD: Basic and Clinical Neuroscience. London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 134–157. [Google Scholar]

90. Solanto MV. Neuropsychopharmacological mechanisms of stimulant drug action in attentiondeficit hyperactivity disorder: a review and integration. Behav. Brain Res. 1998;94:127–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuropsychopharmacological mechanisms of stimulant drug action in attentiondeficit hyperactivity disorder: a review and integration. Behav. Brain Res. 1998;94:127–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Spencer TJ, et al. In vivo neuroreceptor imaging in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A focus on the dopamine transporter. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:1293–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Cheon KA, et al. Dopamine transporter density in the basal ganglia assessed with [123I]IPT SPET in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2003;30:306–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Dougherty DD, et al. Dopamine transporter density in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 1999;354:2132–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Dresel S, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Binding of [99mTc]TRODAT-1 to the dopamine transporter before and after methylphenidate treatment. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2000;27:1518–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Krause KH, et al. Increased striatal dopamine transporter in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Effects of methylphenidate as measured by single photon emission computed tomography. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;285:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Krause KH, et al. Stimulant-like action of nicotine on striatal dopamine transporter in the brain of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5:111–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Krause KH, et al. The dopamine transporter and neuroimaging in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2003;27:605–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Larisch R, et al. Striatal dopamine transporter density in drug naive patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2006;27:267–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Volkow ND, et al. Brain dopamine transporter levels in treatment and drug naive adults with ADHD. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1182–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Corrigall WA, et al. Self-administered nicotine activates the mesolimbic dopamine system through the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res. 1994;653:278–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Brody AL, et al. Smoking-induced ventral striatum dopamine release. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:1211–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Koelega HS. Stimulant drugs and vigilance performance: A review. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1993;111:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Rezvani AH, Levin ED. Cognitive effects of nicotine. Biol. Psychiatry. 2001;49:258–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Hahn B, Stolerman IP. Nicotine-induced attentional enhancement in rats: Effects of chronic exposure to nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:712–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Levin ED, et al. Transdermal nicotine effects on attention. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1998;140:135–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Warburton DM, Mancuso G. Evaluation of the information processing and mood effects of a transdermal nicotine patch. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1998;135:305–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Sacco KA, et al. Effects of cigarette smoking on spatial working memory and attentional deficits in schizophrenia: involvement of nicotinic receptor mechanisms. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:649–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Levin ED, et al. Nicotine effects on adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1996;123:55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol. Bull. 1997;121:65–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. McClernon FJ, et al. Transdermal nicotine attenuates depression symptoms in nonsmokers: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2006;189:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Potter AS, Newhouse PA. Effects of acute nicotine administration on behavioral inhibition in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2004;176:182–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Potter AS, Newhouse PA. Acute nicotine improves cognitive deficits in young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2008;88:407–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Levin ED, et al. Effects of chronic nicotine and methylphenidate in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2001;9:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. Wilens TE, et al. A pilot controlled clinical trial of ABT-418, a cholinergic agonist, in the treatment of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:1931–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Wilens TE, et al. ABT-089, a neuronal nicotinic receptor partial agonist, for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: Results of a pilot study. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;59:1065–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Downey KK, et al. Personality differences related to smoking and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Subst. Abuse. 1996;8:129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Bagwell CL, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and problems in peer relations: Predictions from childhood to adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2001;40:1285–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Doran N, et al. Impulsivity and smoking relapse. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:641–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. DuBois DL, Silverthorn N. Do deviant peer associations mediate the contributions of self-esteem to problem behavior during early adolescence? A 2-year longitudinal study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2004;33:382–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

120. Lejuez CW, et al. The Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) differentiates smokers and nonsmokers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003;11:26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Mitchell SH. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1999;146:455–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. Pomerleau CS. Co-factors for smoking and evolutionary psychobiology. Addiction. 1997;92:397–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. Reynolds B, et al. Delay discounting and probability discounting as related to cigarette smoking status in adults. Behav. Processes. 2004;65:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Finzi-Dottan R, et al. ADHD, temperament, and parental style as predictors of the child’s attachment patterns. Child Psychiatry. Hum. Dev. 2006;37:103–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. Harakeh Z, et al. Parental factors and adolescents’ smoking behavior: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Prev. Med. 2004;39:951–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Laucht M, et al. Association between ADHD and smoking in adolescence: Shared genetic, environmental and psychopathological factors. J. Neural. Transm. 2007;114:1097–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

127. Marshal MP, Molina BS. Antisocial behaviors moderate the deviant peer pathway to substance use in children with ADHD. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2006;35:216–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

128. Simons-Morton B, et al. Peer and parent influences on smoking and drinking among early adolescents. Health Educ. Behav. 2001;28:95–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

129. Dobbins M, et al. Effective practices for school-based tobacco use prevention. Prev. Med. 2007;46:289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

130. Thomas R, Perera R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006;3:CD001293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

131. Hoza B. Peer functioning in children with ADHD. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007;32:655–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

132. Molina BS, et al. Coping skills and parent support mediate the association between childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and adolescent cigarette use. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2005;30:345–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

133. Dwoskin LP, et al. Review of the pharmacology and clinical profile of bupropion, an antidepressant and tobacco use cessation agent. CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12:178–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

134. Wilens TE, et al. Bupropion XL in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:793–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

135. Monuteaux MC, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of bupropion for the prevention of smoking in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68:1094–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

136. Upadhyaya HP, et al. Bupropion SR in adolescents with comorbid ADHD and nicotine dependence: A pilot study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2004;43:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

137. Safren SA. Cognitive–behavioral approaches to ADHD treatment in adulthood. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67 Suppl 8:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gimranov Rinat Fazylzhanovich

Neurologist, neurophysiologist, experience - 33 years;

Professor of Neurology, MD;

Clinic for Rehabilitation Neurology. About the author

Publication date: February 12, 2017

Updated: November 16, 2022

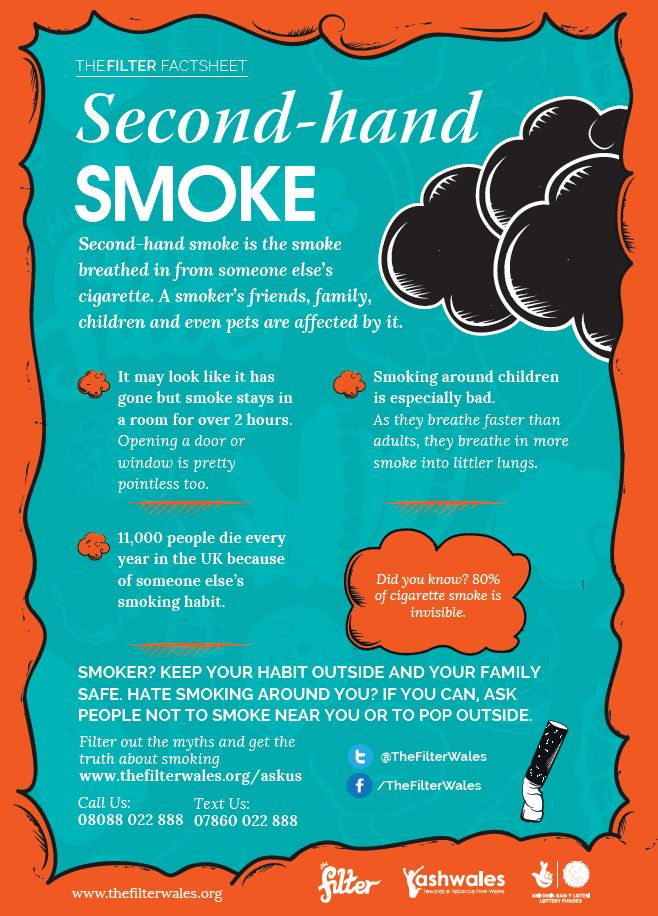

Smoking is closely associated with diseases not only of the lungs. Even one cigarette a day increases the risk of early development of vascular atherosclerosis and contributes to its progression. With the popularization of smoking, neurologists attribute an increase in the number of children suffering from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Studies show that smoking has a detrimental effect not only on the body of the smoker, but also on his offspring. Sex cells from tobacco smoke lose their activity, genetic mutations occur in them. The smoking of a pregnant mother is dangerous, the tobacco atmosphere after birth is harmful to the child.

Contents of the article:

- 1 How tobacco smoking affects a person

- 2 Parental smoking and ADHD in children

- Gimranov.

- 4 Literature sources

How tobacco smoking affects a person

Morbidity and mortality among smokers are significantly higher compared to non-smokers. Sex dependence has not been established: the health of smokers is worse among both men and women.

Parental smoking and ADHD in children

Analyzed 55,000 children under the age of 12, taking into account factors such as the level of education of parents and income in the family. It was found that in families where people smoked at home, children were more likely to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). These children exhibit poor behavior and learning, as well as dyslexia, dysgraphia, and other abnormalities.

Cigarette and pipe drinkers among those who died of lung cancer account for about 90%. And, although now cigarette manufacturers are arguing about the overestimated harm to health of their products, such statements should not be trusted.

A large-scale study of how smoking of pregnant women affects newborns, speaks of negative phenomena. The statistics included 3500 newborns. And it turned out that if a woman smoked during pregnancy, the risk of pulmonary pathology in their children grew 6 times. Statistically significantly more, there were other pathologies:

- fetal malnutrition due to vasospasm of the placenta;

- risk of preterm birth;

- placental abruption;

- retarded mental and intellectual development of infants;

- minimal brain dysfunction in children.

Massive changes occur in the brains of children whose mothers smoked. Also passive smoking is not harmless to the baby.

The risks to the intelligence of children whose families smoke are more than 50 percent higher, especially for boys. Also, all children in whose house they smoke, carcinogens are found in the body.

In 90 percent of children, nitrosamine was found in the blood, and in 95 percent - cotinine (nicotine metabolite).

It is important that the level of these substances in children was significantly higher than in adult passive smokers. The reason is the immaturity of the detoxification systems of the child's body.

Stopping smoking helps the body to restore its resources. But this is not happening as fast as we would like. So that nicotine does not have a harmful effect on the child, mom and dad need to quit smoking at least 6 months before conception. And do not start later, after replenishing the family.

Comments by Professor R.F. Gimranov.

“In the modern world, there are so many external factors that can lead to damage to the nervous system. When parents deliberately smoke at home and thereby harm the health, as well as the proper development of the brain and psyche of children, it can be regarded as a crime. ”

Literature

Andersson, Anneli et al. “Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and smoking habits in pregnant women.” PloS one vol. 15.6 e0234561. Jun 18 2020, doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0234561.

Was this article helpful?

You can subscribe to our newsletter and learn a lot of interesting things about the treatment of the disease, scientific achievements and innovative solutions:

Your e-mail

I agree with the privacy policy and the processing of personal data

Please leave this field empty.

We're sorry!

How can this article be improved?

Please leave this field empty.

For more information, you can check with neurologists on our forum!Go to the Forum

Gimranov Rinat Fazylzhanovich

Make an appointment with a specialist

×

Is it useful for people with mental illness to quit smoking and are they able to do it?

June 8th, 2017

KEY POINTS: Quitting smoking improves mental health.

People with mental health problems are just as motivated and able to quit smoking as other people who smoke. In the treatment of patients with psychiatric disorders, the promotion and support of smoking cessation should be given high priority, as this helps to improve their physical and mental health.

WHAT IS THE QUESTION?

Over the years, opinions have been expressed that smoking can be good for people with mental illness, that they are unwilling or unable to stop smoking, and that work in this direction is not a priority.

WHAT FACTS SHOW THIS QUESTION IS RELEVANT?

- Smoking rates among people with mental disorders are high, especially for the most severe cases [1] , and for people with schizophrenia or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). According to one review of studies on smoking and schizophrenia conducted in 20 countries, including 12 countries in the WHO European Region, the prevalence of smoking among people with schizophrenia was 62% [2] .

According to another review, the estimated rates of smoking among people with clinical PTSD were 40-86% [3] .

- Smoking rates are also high among people with depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, stress [4] , ADHD [5] [6] , and Alzheimer's disease [7] .

- Mental health professionals often do not consider smoking as a priority issue. This is largely due to common misconceptions about smoking and mental illness [8] , including the following:

- Many physicians and other healthcare professionals believe that smoking and mental illness are inextricably linked and that achieving the goal of quitting smoking among people with mental disorders is very difficult or impossible;

- Some people believe that smoking is a useful or necessary form of self-medication for people with mental illness;

- Some people believe that people with mental illness do not want to quit smoking, that they are unable to do so, or that quitting smoking will complicate mental illness treatment;

- Some people believe that implementing a smoke-free mental health facility will be difficult and will create additional problems.

WHAT IS REALITY?

- Smoking is a major reason why people with conditions such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other major mental illnesses live 10-15 years less than the general population [9] [10] [11] .

- Smoking has a negative impact on a person's mental health. Levels of stress, irritability and depressed mood are often higher in smokers than in non-smokers [12] . In addition, smoking has a negative impact on mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression [13] [14] [15] . Smoking is also associated with more severe symptoms and with suicidal ideation or suicide attempts in people with bipolar disorder [16] [17] .

- Smoking may be a causative factor in the development of mental illnesses such as major depression [18] and Alzheimer's disease [7] .

- While mental health professionals are ideally placed to help their patients quit smoking, many are reluctant to address the issue, either in terms of treatment or advocacy for healthy lifestyles in their patients [19] [20] .

- The activities of the tobacco industry are an important reason why misconceptions about smoking and mental health continue to exist. In particular, tobacco companies have funded research supporting the self-medication hypothesis of smoking [8] and claims that smoking reduces stress [21] or Alzheimer's symptoms [22] . Many of these studies were poorly designed, and therefore more robust non-tobacco funded studies produced different results [7] .

- To promote their products, tobacco companies seek to make people with mental disorders their customers [8] . In particular, they provided mental health services with financial donations and free cigarettes [23] , and opposed smoking bans in psychiatric hospitals, arguing that the practice was "inhumane or even inhumane" [24] .

- Smoking cessation has a positive effect on a person's mental health. Compared with continuing to smoke, quitting the habit is associated with lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, and with improved mood and quality of life [25] and may reduce symptoms of disorders such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) [26] .

- In patients taking certain medications, smoking cessation can also reduce their dosage. In particular, after quitting smoking, the dosage of some antipsychotic drugs can be reduced, sometimes even by 25%, which in turn reduces the number of side effects and long-term risks associated with the use of these drugs [27] .

- There is also strong evidence that when people with mental illness stop smoking, it does not lead to the development of new mental health problems [25] .

- While some smokers with psychiatric disorders experience more severe nicotine withdrawal symptoms than other smokers smoking cessation, and other evidence-based interventions [29] [30] .

- Smokers with mental disorders often want to quit smoking [31] [32] and with the right degree of encouragement and support they are able to do so [33] .

- When smoking bans and restrictions in mental health settings are carefully designed and implemented with appropriate patient support, the predicted negative outcomes do not occur and the overall effect is very positive [1] [34] [35] .

In the United Kingdom, for example, the following benefits have been noted: improved sleep-wake cycles among patients, reduced risk of self-harm from lighters, and the conversion of former smoking areas into new recreational facilities [36] .

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Taking action to reduce smoking among people with mental illness should be a top priority for both the health system and practitioners. This practice will make a huge contribution to narrowing the gap in life expectancy between people with mental disorders and the general population.

- The high rates of smoking among people with mental illness have enormous negative consequences for their mental and physical well-being and are a major contributor to the significantly lower life expectancy in this already disadvantaged population.

- Like other smokers, smokers with mental disorders want to quit and, with the right amount of encouragement and support, are able to do so.

- When properly planned and implemented, smoking bans in mental health settings are effective and do not lead to predictable adverse effects.

- Taking action to reduce smoking among people with mental illness should be a high priority under international instruments such as the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and human rights treaties, including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [37] and the Universal human rights declaration [38] , which states that everyone has the right to health without any discrimination.

Show References

-

Smoking and Mental Health. 2013; Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Psychiatrists (http://www.ncsct.co.uk/usr/pub/Smoking%20and%20mental%20health.pdf) ↩︎ ↩︎

-

de Leon J, Diaz FJ. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophr Res 2005;76:135-157.

↩︎

-

Fu SS, McFall M, Saxon AJ, et al. Post traumatic stress disorder and smoking: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 2007;9:1071-1084. ↩︎

-

McClave AK, McKnight-Eily LR, Davis SP, Dube SR. Smoking characteristics of adults with selected lifetime mental illnesses: results from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Pub Health 2010;100:2464-2472. ↩︎

-

Wilens TE, Vitulano M, Upadhyaya H, et al. Cigarette smoking associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr 2008;153:414-419. ↩︎

-

Matthies S, Holzner S, Feige B, et al. ADHD as a serious risk factor for early smoking and nicotine dependence in adulthood. J Attention Dis 2013;17:176-186. ↩︎

-

Cataldo JK, Prochaska J, Glantz S. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: an analysis controlling for tobacco industry affiliation. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;19:465-480. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Prochaska JJ. Smoking and mental illness: breaking the link.

N Engl J Med 2011;365:196-198. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Callaghan RC, Veldhuizen S, Jeysingh T, et al. Patterns of tobacco-related mortality among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. J Psych Res 2014;48:102- ↩︎

-

Tam J, Warner KE, Meza R. Smoking and the reduced life expectancy of individuals with serious mental illness. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:958-966. ↩︎

-

Lawrence D, Hancock KJ, Kisely S. The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: retrospective analysis of population based registers. Brit Med J 2013;346:f2539. ↩︎

-

Parrott AC, Murphy RS. Explaining the stress-inducing effects of nicotine to cigarette smokers. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp 2012;27:150-155. ↩︎

-

Williams JM, Ziedonis D. Addressing tobacco among individuals with a mental illness or an addiction. Addict Behav 2004;29:1067-1083. ↩︎

-

Picciotto MR, Brunzell DH, Caldarone BJ.

Effect of nicotine and nicotinic receptors on anxiety and depression. Neuroreport 2002;13:1097-1106. ↩︎

-

Mendelsohn C. Smoking and depression: a review. Austr Family Phys 2012;41:304-307. ↩︎

-

Ostacher MJ, Nierenberg AA, Perlis RH, et al. The relationship between smoking and suicidal behavior, comormidity, and course of illness in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatr 2006;67:1907-1911. ↩︎

-

Ostacher M, LeBeau RT, Perlis RH, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with suicidality in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Dis 2009;11:766-771. ↩︎

-

Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Cigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohort. Brit J Psych 2010;196:440-446. ↩︎

-

Williams JM, Stroup TS, Brunette MF, Raney LE. Tobacco use and mental illness: a wake-up call for psychiatrists. PsychServ 2014;65:1406-1408. ↩︎

-

Lawn S, Condon J. Psychiatric nurses' ethical stance on cigarette smoking by patients: determinants and dilemmas in their role in supporting cessation.

Int J Mental Health 2006;15:111-118. ↩︎

-

Petticrew MP, Lee K. The "father of stress" meets "big tobacco": Hans Selye and the tobacco industry. Am J Pub Health 2011;101:411-417. ↩︎

-

Cataldo JK, Glantz SA. Smoking cessation and Alzheimer's disease: facts, fallacies and promise. Expert Rev Neurother 2010;10:629-631. ↩︎

-

Apollonio DE, Malone RE. Marketing to the marginalized: tobacco industry targeting of the homeless and mentally ill. Tob Control 2005;14:409-415. ↩︎

-

Prochaska JJ, Hall SM, Bero LA. Tobacco use among individuals with schizophrenia: what role has the tobacco industry played? Schizophr Bull 2008;34:555-567. ↩︎

-

Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, et al. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Brit Med J 2014;348:g1151. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Pagano ME, Delos-Reyes CM, Wasilow S, Svala KM, Kurtz SP. Smoking cessation and adolescent treatment response with comorbid ADHD.

J Subst Abuse Treatment 2016;70:21-27. ↩︎

-

Desai HD, Seabolt J, Jann MW. Smoking in patients receiving psychotropic medications. CNS Drugs 2001;15:469-494. ↩︎

-

Weinberger AH, Desai RA, McKee SA. Nicotine withdrawal in US smokers with current mood, anxiety, alcohol use, and substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010;108:7- ↩︎

-

Evins A, Cather C. Effective Cessation Strategies for Smokers with Schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol 2015;124:133-147. ↩︎

-

Ziedonis D, Das S, Tonelli M. Smoking and mental illness: strategies to increase screening, assessment, and treatment. Focus J Lifelong Learning Psych 2015;13:290-306. ↩︎

-

Caosella AM, Ossip-Klein DJ, Owens CA. Smoking attitudes, beliefs, and readiness to change among acute and long term care inpatients with psychiatric diagnoses. Addict Behav 1999;24:331-344. ↩︎

-

Siru R, Hulse GK, Tait RJ. Assessing motivation to quit smoking in people with mental illness: a review.

Addiction 2009;104:719-733. ↩︎

-

Hitsman B, Borrelli B, McChargue DE, Spring B, Niaura R. History of depression and smoking cessation outcome: a meta-analysis. J Consul Clin Psych 2003;71:657-663. ↩︎

-

Cormac I, Creasey S, McNeill A, Ferriter M, Huckstep B, D'Silva K. Impact of a total smoking ban in a high secure hospital. Brit J Psych Bull 2010;34:413-417. ↩︎

-

Lawn S, Pols R. Smoking bans in psychiatric inpatient settings? A review of the research. Austr NZ J Psych 2005;39:866-885. ↩︎

-

Fact sheet: Smoking and Mental Health. 2016; ASH UK (http://ash.org.uk/files/documents/ASH_120.pdf). ↩︎

-

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2006; Paris; United Nations, 2006 (http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml). ↩︎

-

Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948; Paris: United Nations (http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml). ↩︎

- Human health influence

- Politics to ensure Begrant environment

- Young people

- Support Intervices for the cessation of tobacco use 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9 as of May 29th, 2017.