Adderall and aspergers

Adderall and Aspergers : aspergers

So i was diagnosed Aspergers in 7th grade, a little over a decade ago, but i have never received medication for anything. My mom was always opposed to medication growing up. I have tried all major natural methods to help. Therapy(lots of therapy). Meditation. Regular exercise. Eating healthy. Nothing has seriously helped my ability to function in life and society, and as such since i graduated high school i have not progressed in the slightest. I have finally decided i would like to pursue medication to see if that helps. Awhile back a friend allowed me access to some of his Adderall, i was curious if it would help. So i used 1 pill every day for a week. The effects were amazing! Increased attention, increased motivation to take care of basic daily needs i normally neglect, increased confidence, easier to look people in the eyes, social anxiety severely lessened, i even had an easier time understanding body language and nonverbal communication and i knew just what to say instead of lamely avoiding lengthy conversation at all cost.

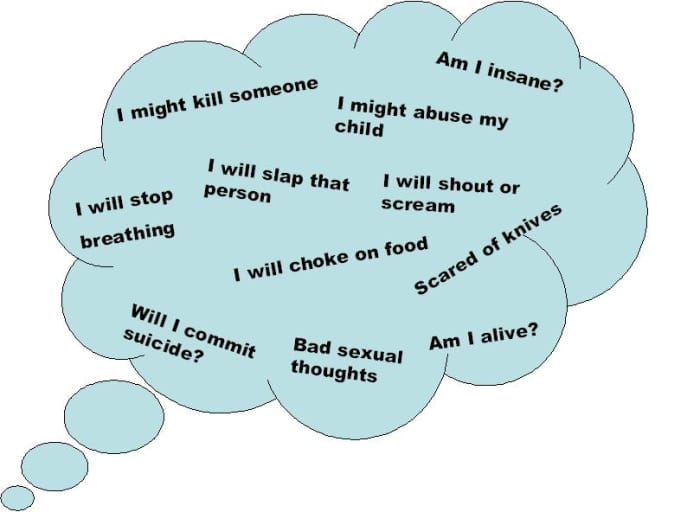

When people normally would joke with me, i don't understand what they mean so i opt to remain silent out of fear of either being mocked or reacting in a way contrary to their intended goal. I was able to socialize so well in fact that when people joked with me, i was, for the first time, able to joke back and participate in witty banter instead of assuming they are making fun of me and slinking into depression and self loathing. It was the first time in my life i really felt able to truly function in society. I want to see a psychiatrist about getting prescribed Adderall, but because what i did is illegal, i don't want to mention the limited experience i had for fear of being turned away for drug seeking. I guess technically i am, but only because i sincerely believe it enhances my quality of life.

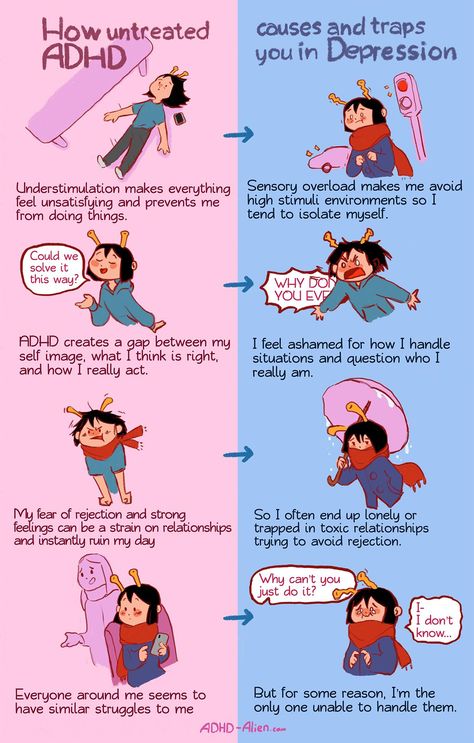

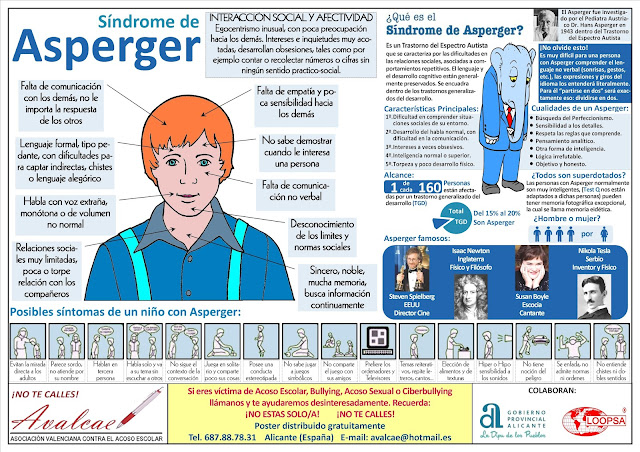

So i have an idea. Since i am diagnosed Aspergers, i want to make an appointment and explain that i want to seek treatment for my Aspergers. They have no treatment for it, only the symptoms. Aspergers VERY frequently coexists with ADHD, both have genetic components and both Aspergers and ADHD run STRONGLY in my family. Most of my family have ADHD and many have Aspergers. I have never been diagnosed ADHD, but since most of my family has my mom has always told me its almost a certainty i have it too. As i said earlier growing up my mom was opposed to medication. But she finally got prescribed Adderall for her ADHD over a year ago and after seeing how much it changed her life, she confided in me that now she believes if I was medicated when i was younger, i would have probably done better in life growing up. From my research i have almost every symptom of ADHD and have since at least 3rd grade, so i will request the test after explaining it runs in my family. My old therapist suspected i have it, but i never got diagnosed. My sessions were purely focused on helping me cope with my autism and the socially debilitating affects of it. Anything else was put to the side until i eventually stopped going to therapy because of unemployment.

Aspergers VERY frequently coexists with ADHD, both have genetic components and both Aspergers and ADHD run STRONGLY in my family. Most of my family have ADHD and many have Aspergers. I have never been diagnosed ADHD, but since most of my family has my mom has always told me its almost a certainty i have it too. As i said earlier growing up my mom was opposed to medication. But she finally got prescribed Adderall for her ADHD over a year ago and after seeing how much it changed her life, she confided in me that now she believes if I was medicated when i was younger, i would have probably done better in life growing up. From my research i have almost every symptom of ADHD and have since at least 3rd grade, so i will request the test after explaining it runs in my family. My old therapist suspected i have it, but i never got diagnosed. My sessions were purely focused on helping me cope with my autism and the socially debilitating affects of it. Anything else was put to the side until i eventually stopped going to therapy because of unemployment. I have a new job i am starting soon and my insurance is really good, i have never seen a psychiatrist before though so i am not sure what to expect from the visit. I am quite sure i do have ADHD, which i suspect is why the Adderall actually helped me, from what i have seen with autism it can be hit or miss. It helps some people and others hate it with a passion.

I have a new job i am starting soon and my insurance is really good, i have never seen a psychiatrist before though so i am not sure what to expect from the visit. I am quite sure i do have ADHD, which i suspect is why the Adderall actually helped me, from what i have seen with autism it can be hit or miss. It helps some people and others hate it with a passion.

Autism’s drug problem | Spectrum

Many people on the spectrum take multiple medications — which can lead to serious side effects and may not even be effective.

Illustrations by Keith Negley

Connor was diagnosed with autism early — when he was just 18 months old. His condition was already obvious by then. “He was lining things up, switching lights on and off, on and off,” says his mother, Melissa. He was bright, but he didn’t speak much until age 3, and he was easily frustrated. Once he started school, he couldn’t sit still in class, called out answers without raising his hand and got visibly upset when he couldn’t master a math concept or a handwriting task quickly enough. “One time, he rolled himself up into the carpet like a burrito and wouldn’t come out until I got there,” Melissa recalls. (All families in this story are identified by first name only, to protect their privacy.)

“One time, he rolled himself up into the carpet like a burrito and wouldn’t come out until I got there,” Melissa recalls. (All families in this story are identified by first name only, to protect their privacy.)

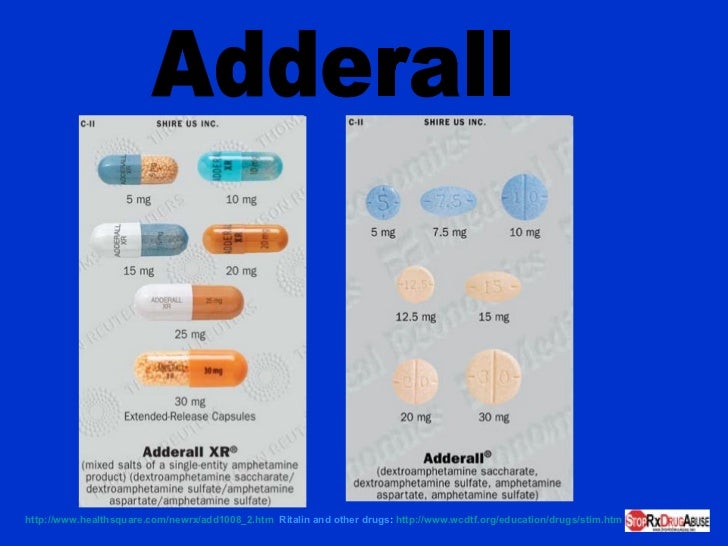

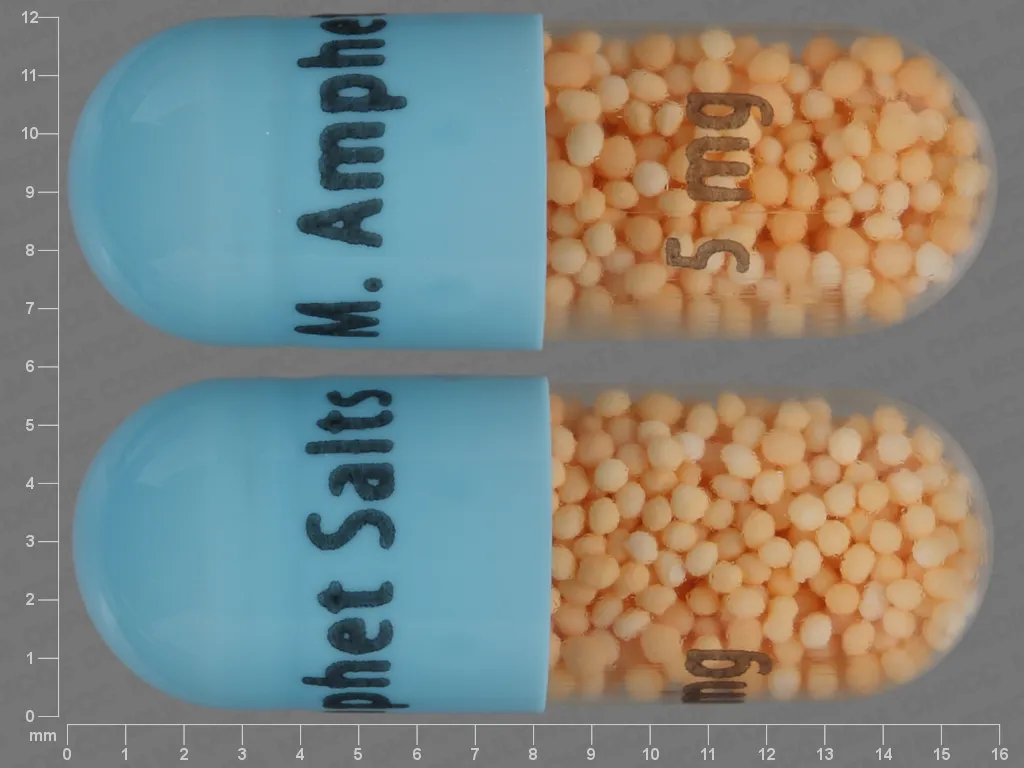

Connor was prescribed his first psychiatric drug, methylphenidate (Ritalin), at age 6. That didn’t last long, but when he was 7, his parents tried again. A psychiatrist suggested a low dose of amphetamine and dextroamphetamine (Adderall), a stimulant commonly used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The drug seemed to improve his time at school: He was able to sit still for longer periods of time and focus on what his teachers were saying. His chicken-scratch handwriting became legible. Then, it became neat. Then perfect. And then it became something Connor began to obsess over.

“We were told that these are the gives and takes; if it’s helping him enough to get through school, you have to decide if it’s worth it,” Melissa says. It was worth it — for a while.

But when the Adderall wore off each day, Connor had a tougher time than ever. He spent afternoons crying and refusing to do much of anything. The stimulant made it difficult for him to fall asleep at night. So after a month or two, his psychiatrist added a second medication — guanfacine (Intuniv), which is commonly prescribed for ADHD, anxiety and hypertension, but can also help with insomnia. The psychiatrist hoped it might both ease Connor’s afternoons and help him sleep.

In some ways, it had the opposite effect. His afternoons did get slightly better, but Connor developed intense mood swings and was so irritable that every evening was a struggle. Rather than simply tossing and turning in bed, he refused to even get under the covers. “He wouldn’t go to bed because he was always angry about something,” Melissa says. “He was getting himself all wound up, carrying on, getting upset at night and crying.”

After seven months, his parents declared the combination unsustainable. They swapped guanfacine for over-the-counter melatonin, which helped Connor fall asleep with no noticeable side effects. But within a year, he had acquired a tolerance for Adderall. Connor’s psychiatrist increased his dosage and that, in turn, triggered tics: Connor began jerking his head and snorting. Finally, at his 9-year physical, his doctor discovered that he’d only grown a few inches since age 7. He also hadn’t gained any weight in two years; he’d dropped from the 50th percentile in weight to the 5th.

They swapped guanfacine for over-the-counter melatonin, which helped Connor fall asleep with no noticeable side effects. But within a year, he had acquired a tolerance for Adderall. Connor’s psychiatrist increased his dosage and that, in turn, triggered tics: Connor began jerking his head and snorting. Finally, at his 9-year physical, his doctor discovered that he’d only grown a few inches since age 7. He also hadn’t gained any weight in two years; he’d dropped from the 50th percentile in weight to the 5th.

That was the end of all the experiments. His parents took him off all prescription drugs, and today, at almost 13 years old, Connor is still medication-free. His tics have mostly disappeared. Although he has trouble maintaining focus in class, his mother says that the risk-benefit ratio of trying another drug doesn’t seem worth it. “Right now we’re able to handle life without it, so we do.”

Connor is just one of the many, many children with autism who are given multiple prescriptions. Phoenix was only 4 when he started taking risperidone (Risperdal), a drug approved for irritability in autism. Now 15, he has taken more than a dozen different medications. Ben, 34, has autism, but for years he was misdiagnosed with other conditions. He was in middle school when his mother insisted he take drugs for his depression and disruptive behaviors. His doctor tried one antidepressant after another; nothing worked. In high school, at 15, he was misdiagnosed again, this time with bipolar disorder, and given an anticonvulsant and an antidepressant.

Phoenix was only 4 when he started taking risperidone (Risperdal), a drug approved for irritability in autism. Now 15, he has taken more than a dozen different medications. Ben, 34, has autism, but for years he was misdiagnosed with other conditions. He was in middle school when his mother insisted he take drugs for his depression and disruptive behaviors. His doctor tried one antidepressant after another; nothing worked. In high school, at 15, he was misdiagnosed again, this time with bipolar disorder, and given an anticonvulsant and an antidepressant.

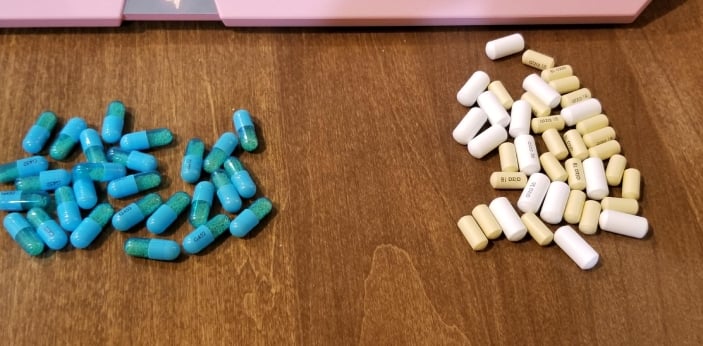

For Connor, eliminating prescription drugs was difficult, but doable. For others, multiple medications may seem indispensable. It’s not unusual for children with autism to take two, three, even four medications at once. Many adults with the condition do so, too. Data are scant in both populations, but what little information there is suggests multiple prescriptions are even more common among adults with autism than in children. Clinicians are particularly concerned about children with the condition because psychiatric medications can have long-lasting effects on their developing brains, and yet are rarely tested in children.

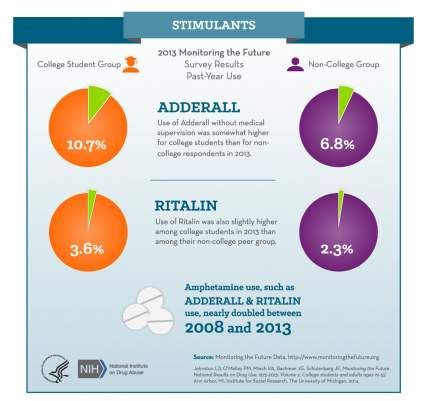

In general, polypharmacy — most often defined as taking more than one prescription medication at once — is commonplace in people with autism. In one study of more than 33,000 people under age 21 with the condition, at least 35 percent had taken two psychotropic medications simultaneously; 15 percent had taken three.

“Psychotropic medications are used pretty extensively in people with autism because there aren’t a lot of treatments available,” says Lisa Croen, director of the Autism Research Program at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California. “Is heavy drug use bad? That’s the question. We don’t know; it hasn’t been studied.”

Sometimes, as in Connor’s case, a second drug is prescribed to treat the side effects of the first. More often, doctors prescribe drugs for each individual symptom — stimulants for focus, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for depression, antipsychotics for aggression and so on. (Children with autism who have epilepsy also typically take anticonvulsants. But because those drugs are effective and easy to assess, they’re usually not seen as part of the polypharmacy problem.)

But because those drugs are effective and easy to assess, they’re usually not seen as part of the polypharmacy problem.)

“Kids come in on Zoloft, Depakote and risperidone,” says Matthew Siegel, assistant professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. “Zoloft is an antidepressant, Depakote is a mood stabilizer, and risperidone is an antipsychotic — three psychotropic medications that are being prescribed for one individual.”

Other times, due to moves or changes in coverage or just a lack of rapport, people on the spectrum end up seeing multiple doctors, all of whom have their own ideas about treatment and may add a new drug without removing another.

The reason for this confusion: No existing medication treats the underlying condition.

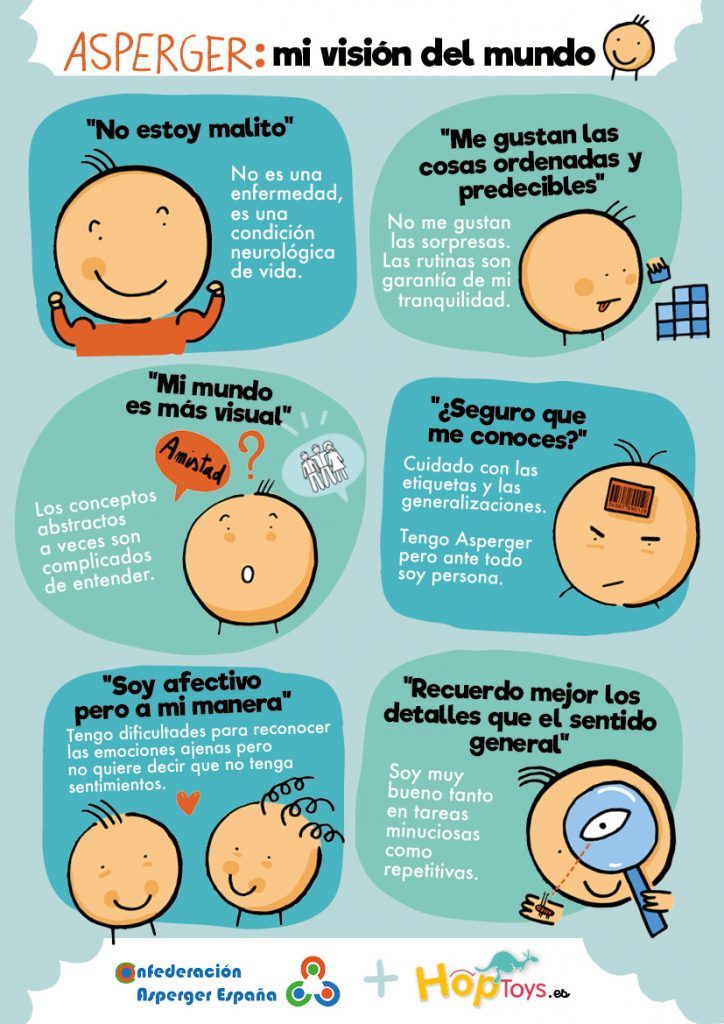

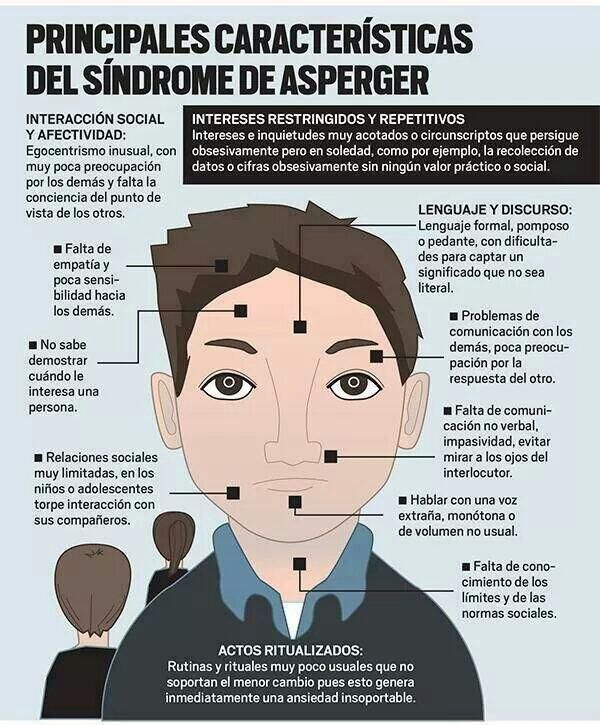

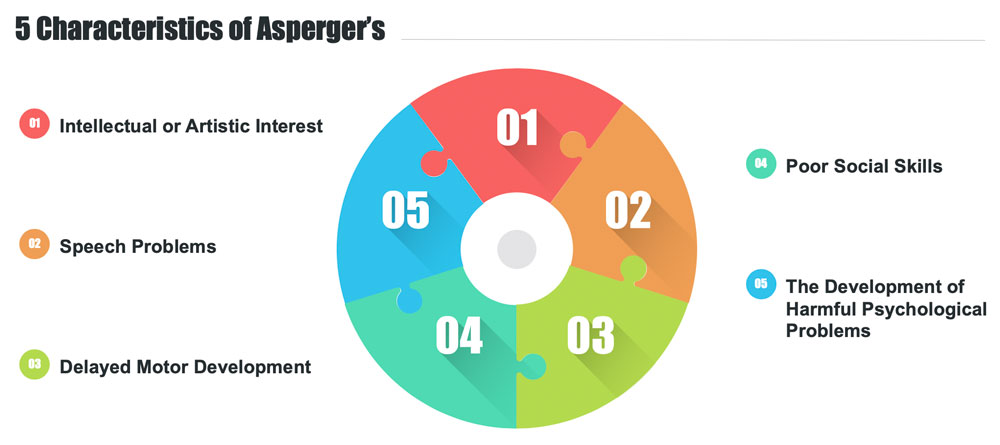

The core characteristics of autism include repetitive behaviors, difficulty with social interactions and trouble communicating. Therapy can help, but no medication so far can improve these problems. Instead, drugs merely treat some of the peripheral features — ADHD, irritability, anxiety, aggression, self-injury — that make life challenging for people with autism.

Instead, drugs merely treat some of the peripheral features — ADHD, irritability, anxiety, aggression, self-injury — that make life challenging for people with autism.

This practice that can put people on a drug cocktail that may not be effective or appropriate. Each clinician must make her own best guess about what works and is safe, because there’s simply not yet enough research. “We have so few studies that have looked at single drugs, and so few studies that have even directly compared single drugs,” says Bryan King, vice chair of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. “There’s such a long path to go down before we get to a point where we see these specific combinations studied.”

“Is heavy drug use bad? That’s the question. We don’t know; it hasn’t been studied.” Lisa CroenThe straight dope:

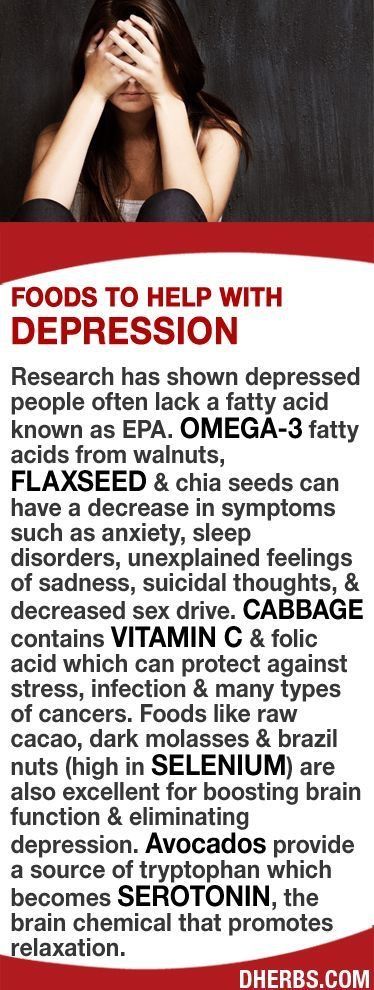

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved only two drugs for children and adolescents with autism: risperidone and aripiprazole (Abilify), both atypical antipsychotics prescribed for behaviors associated with irritability, such as aggression, tantrums and self-harm. The drugs help ease these behaviors about 30 to 50 percent of the time, but leave others untouched. And that’s a major gap: Psychiatric problems are common in children with autism. According to a 2010 study, more than 80 percent of children with autism at a psychiatric healthcare center also had ADHD, 61 percent had at least two anxiety disorders, and 56 percent had major depression.

The drugs help ease these behaviors about 30 to 50 percent of the time, but leave others untouched. And that’s a major gap: Psychiatric problems are common in children with autism. According to a 2010 study, more than 80 percent of children with autism at a psychiatric healthcare center also had ADHD, 61 percent had at least two anxiety disorders, and 56 percent had major depression.

Multiple diagnoses lead to drug cocktails, but no clinical trials have tested combinations of the most commonly used medications, so potential drug-drug interactions are unknown. “Every drug has side effects, and when you start to mix them together you’re looking at something that’s not been studied,” King says. “And in autism, where you might have communication impairments, it’s even more worrisome because people are less likely to be able to tell you that your medicines are making them feel sick.”

Beyond that, say researchers, is the fact that the medicines may not even work.

“Many studies have looked at the use of ADHD meds to treat ADHD symptoms in people with autism. The same can be said for obsessive-compulsive disorder and repetitive behaviors,” says Daniel Coury, a developmental pediatrician at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. “And with virtually all of these, we find that they don’t work as well as they do in people who don’t have autism.”

The same can be said for obsessive-compulsive disorder and repetitive behaviors,” says Daniel Coury, a developmental pediatrician at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. “And with virtually all of these, we find that they don’t work as well as they do in people who don’t have autism.”

That research, too, is relatively sparse and is composed mostly of uncontrolled studies. One 2013 meta-analysis concluded that most studies of psychiatric drugs for autism features are either too small or don’t have the right design to determine whether the drugs are effective. The research that does exist, the researchers wrote in that study, “is only suggestive, and awaits true assessment in properly controlled studies.”

Symptoms of depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD and other conditions in people with autism seem similar to those that people without autism may experience. But because the underlying cause is different, the biochemistry may be different overall — and also highly variable from person to person.

“That is a big problem for any treatment in autism,” Siegel says. With so many genetic variations underlying autism, each individual’s situation is different, so any treatment needs to be tailored to that individual. Depending on the drug, as little as 20 percent of people may benefit from a drug, even within the ideal conditions of a clinical study. In this milieu, aripiprazole and risperidone stand out because they work up to 50 percent of the time; “50 percent is like a homerun,” Siegel says.

Paradoxically, another reason children and adults with autism may take multiple drugs is because — as in Connor’s case — doctors prescribe a second medication to mitigate side effects from the first. Antipsychotics, for instance, can cause weight gain and metabolic problems, or even involuntary twitching. Some doctors add metformin to address the weight gain, or benztropine (Cogentin) to ease the jerky movements.

But each additional prescription comes with its own potential side effects. Metformin can cause muscle pain and, less commonly, anxiety and nervousness; benztropine can lead to confusion and memory problems. Doctors less experienced in treating autism might misinterpret these drug effects as new symptoms, and be tempted to medicate them in turn. The great majority of psychotropics are prescribed by primary care doctors who have little or no experience with autism, says Siegel. “If people don’t know what they’re doing, you might imagine that kids are more likely to end up on multiple medications.”

Metformin can cause muscle pain and, less commonly, anxiety and nervousness; benztropine can lead to confusion and memory problems. Doctors less experienced in treating autism might misinterpret these drug effects as new symptoms, and be tempted to medicate them in turn. The great majority of psychotropics are prescribed by primary care doctors who have little or no experience with autism, says Siegel. “If people don’t know what they’re doing, you might imagine that kids are more likely to end up on multiple medications.”

As a pre-teen, Ben had many struggles typical of a child with autism: social anxiety, difficulty fitting in with his peers, mild depression, fits of intense anger, and a tendency to be both inattentive and disruptive in class. When he was 12, a school assessment found that he had sensory processing issues and dysgraphia — difficulty with handwriting — but not autism. At his mother’s request, his doctor tried an antidepressant. It didn’t help. It did, however, give him headaches. So did the next antidepressant, and the one after that. The side effects weren’t worth it, so Ben got a reprieve, at least for a little while.

It didn’t help. It did, however, give him headaches. So did the next antidepressant, and the one after that. The side effects weren’t worth it, so Ben got a reprieve, at least for a little while.

Two years later, when he was 16 and having a particularly difficult time in school and at home, his mother insisted he try medication again. Their new family doctor prescribed an antidepressant that had just been introduced, an SSRI called citalopram (Celexa), with instructions that Ben and his mother follow up with a specialist. But life that year was too chaotic for a follow-up, and Ben stayed on citalopram.

Over the next year, school got progressively worse. Ben was increasingly bullied by his peers and increasingly more likely to respond with aggression, so his mother finally took him to a therapist. The therapist diagnosed Ben with bipolar disorder and sent him to a psychiatrist with directions to add valproic acid (Depakote) to the medication mix. Ben recalls that the psychiatrist asked a few questions, then simply handed him a scrip for the two drugs the therapist had requested. Ben’s autism remained unrecognized.

Ben’s autism remained unrecognized.

“That’s when things changed pretty dramatically,” Ben says. He gained 50 pounds. He couldn’t focus during class. He got in shouting matches at school and at home, and his anxiety spiked. “My behavior got much more aggressive and erratic,” he says. He’d wake up, terrified, in the middle of the night and just pace in circles around the room. “I don’t think it would have escalated as much as it did if I hadn’t been medicated,” he says. He got into wrestling matches with his father. “I’d be broken down and sobbing and desperate, and punch a hole in the wall.”

Five medications and five clinicians later, Ben was still lethargic, irritable, angry and having a difficult time focusing.

Nailing down the right drug combination is particularly difficult when there’s little to no continuity of care. In Ben’s case, not only was he misdiagnosed, but his family moved twice. On top of that, his therapist and prescribing psychiatrist weren’t communicating about his diagnosis and treatment. In other cases, people may not have access to doctors with expertise in autism. Some people switch doctors in the hopes of finding one with an approach they like, or when their insurance coverage changes. They may see one physician who provides a 30-day prescription along with instructions to find a clinician to manage their care. But they may then move on to another doctor who provides a different drug with similar instructions. The medications add up “because there is no centralized person,” says Shafali Jeste, a pediatric neurologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “I see it in Los Angeles all the time.”

In other cases, people may not have access to doctors with expertise in autism. Some people switch doctors in the hopes of finding one with an approach they like, or when their insurance coverage changes. They may see one physician who provides a 30-day prescription along with instructions to find a clinician to manage their care. But they may then move on to another doctor who provides a different drug with similar instructions. The medications add up “because there is no centralized person,” says Shafali Jeste, a pediatric neurologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “I see it in Los Angeles all the time.”

Prescription numbers can balloon as children pass through adolescence and into adulthood.

“People get on the medications and tend to stay on [them] for long periods of time without ever really attempting to determine whether it’s still needed,” says David Posey, a psychiatrist in Indianapolis, Indiana. The standard recommendation is to reassess drugs yearly, to evaluate whether a lower dose might work — but that can be difficult to do, he says. “Families are reluctant to take away a medication that’s been really helpful.”

“Families are reluctant to take away a medication that’s been really helpful.”

Jeste says that people often arrive in her clinic with a long list of medications. But with no electronic health records or a complete medical history, she and her colleagues are left trying to guess why each medication was prescribed, what it was originally intended to do, and whether it’s helping. Then, working one drug at a time, they gradually lower the dosages.

Ben wasn’t lucky enough to find that kind of clinician. By his final year of high school, he was falling asleep in class and felt so debilitated that he dropped out. “At the same time, my parents are getting divorced,” Ben says, recalling that period. “There’s all this chaos happening, and I lose all my supports, I lose all my routine, and I start living out of my car.”

He began smoking marijuana, which he says provided him with an amped-up effect in combination with the SSRI. But in some ways it also helped him function. “It was more effective than the medications at helping me be more social,” he says. Ben says marijuana helped him finally recognize the rise-and-fall pattern of drugs’ effects, and that his psychiatric medications were affecting his moods similarly, albeit more slowly. “I got the idea that maybe some of the cycles I was feeling on a regular basis coincided with the way I was taking my prescribed medications,” he says.

Ben says marijuana helped him finally recognize the rise-and-fall pattern of drugs’ effects, and that his psychiatric medications were affecting his moods similarly, albeit more slowly. “I got the idea that maybe some of the cycles I was feeling on a regular basis coincided with the way I was taking my prescribed medications,” he says.

At 21, he decided to wean himself off all drugs, both prescription and recreational. Later that year, he was diagnosed with autism. Now, when he feels the anger rise in him, he says, he steps back and breathes. No more holes in the wall. He runs six days a week, which helps him feel calm, focused and clear-headed. His autism may have prompted his initial moodiness and aggression, but he says it was the medications that sent him into a tailspin.

“This is an experiment that’s going on, but it’s a completely uncontrolled experiment.” Lawrence ScahillThe remedy:

Taking multiple prescriptions isn’t always a bad thing. For children whose lives are severely disrupted, or who pose a danger to themselves or others, they may be the only solution.

For children whose lives are severely disrupted, or who pose a danger to themselves or others, they may be the only solution.

Phoenix was one of those children. “He was a little tornado,” his mother says. One day in early 2007, his daycare called his mother to pick him up early because he was being disruptive, knocking over chairs and tables for no discernable reason. He ran away twice that afternoon — once letting himself out of the car on the way home, and later climbing out his bedroom window. A police patrol found him on the median strip of a busy four-lane thoroughfare, where he had crossed two lanes of traffic. He was just 4.

Phoenix’s mother Sally says he was a complicated little guy from the start. When his moods swung toward anger, he would lash out and try to hurt his older brother, who also has autism. “He had ungodly strength,” she says. In order to keep both boys safe, she knew she had to help him get his anger under control.

His doctor tried him on risperidone, then soon added added guanfacine and Adderall. But his aggression was still out of control. Sally says that every morning when she and her husband woke up, they would look at each other and say, “I wonder what mood Phoenix is going to be in?” And then, she says, “I’d get a knot in my stomach.” It was clear that his medications needed adjusting, but dealing with that at home was more than his family could take. They admitted Phoenix to a hospital for the first time when he was 6.

But his aggression was still out of control. Sally says that every morning when she and her husband woke up, they would look at each other and say, “I wonder what mood Phoenix is going to be in?” And then, she says, “I’d get a knot in my stomach.” It was clear that his medications needed adjusting, but dealing with that at home was more than his family could take. They admitted Phoenix to a hospital for the first time when he was 6.

By 2009, his doctor’s office had already switched psychiatrists twice. The new psychiatrist swapped Adderall out for lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse). Then, when a blood test showed Phoenix was at an elevated risk for developing breasts — a serious but rare side effect of risperidone known as gynecomastia — the psychiatrist switched risperidone for quetiapine (Seroquel). “It was a disaster,” Sally says. Phoenix climbed out of bedroom windows, repeatedly stood up and walked out of his classroom, and attacked his brother unprovoked. None of the combinations eased his aggression or violent mood swings. One day, when he was 7, Phoenix threatened to kill his brother and his brother’s friend because they wouldn’t play with him. He threw a brick at them and chased them with a metal pipe.

One day, when he was 7, Phoenix threatened to kill his brother and his brother’s friend because they wouldn’t play with him. He threw a brick at them and chased them with a metal pipe.

The incident shook his family, and ended with another hospital admittance and new combinations of medications. His doctors replaced quetiapine with another antipsychotic, ziprasidone (Geodon), and kept him on valproic acid and guanfacine. Because Phoenix’s brother, Mac, had been having success with the ADHD medication atomoxetine (Strattera), the hospital staff replaced lisdexamfetamine with atomoxetine.

Phoenix has been in and out of four different residential programs since then, has been hospitalized six times, and has tried a dozen or more medications, as many as four at a time. The hospitalizations helped him wean off some medications and onto others that, at least temporarily, appeared to control his mood swings. But every time he left, the medication combinations slowly lost their potency, and he reverted to aggressive acts, mostly against his brother. The first two residential programs were even less helpful. They created stability and structure: every day the same, every routine consistent and reliable. But the programs weren’t able to adjust his prescriptions as a hospital could. And when he came home, without the rigid routine of a live-in facility, he eventually started attacking his brother. “I have holes in the bedroom doors from Phoenix trying to get to Mac,” Sally says.

The first two residential programs were even less helpful. They created stability and structure: every day the same, every routine consistent and reliable. But the programs weren’t able to adjust his prescriptions as a hospital could. And when he came home, without the rigid routine of a live-in facility, he eventually started attacking his brother. “I have holes in the bedroom doors from Phoenix trying to get to Mac,” Sally says.

The second two programs were tailored to children with autism, and there Phoenix found the help he so badly needed. He was 12 when he started the third program and began taking a new antipsychotic most often prescribed for bipolar disorder, called olanzapine (Zyprexa). And it was during the fourth residential program, when he was 13, that his doctors hit on what seemed to be a winning combination: olanzapine, valproic acid, guanfacine and atomoxetine. He was spending his weekends at home, but during the week he lived at a nearby residential facility where he could get the behavioral and community support he needed. “It was the first time he came home that, for a little bit of time, we really enjoyed his company; we’d get glimpses of the real Phoenix in there,” Sally says.

“It was the first time he came home that, for a little bit of time, we really enjoyed his company; we’d get glimpses of the real Phoenix in there,” Sally says.

But a common side effect of Zyprexa is weight gain; the drug made Phoenix ravenous. “On weekends when he was home, he could empty out my freezer at 3 in the morning,” she says. Over the course of a year, the previously skinny child gained nearly 100 pounds. “He looked like he’d pop if you stuck a pin in him,” says his mother. “He’d just be sitting there and his breathing would be labored. We had to get him off the Zyprexa.” His doctor weaned him off Zyprexa and on to one antipsychotic that didn’t work, and then another, quetiapine (Seroquel), that did.

Today Phoenix, 15, is on a four-drug cocktail and has remained stable for more than a year. His mood has remained stable, too. “The aggression is gone,” Sally says. His sense of humor has emerged, and he can sit still and watch a television program with his family or discuss something he sees on the news. He has also developed a sense of empathy. Now, when a child at his school acts up in a way that he might have done in the past, he tells his brother, “‘I owe you and Mom an apology,’” Sally says. “He’s seen it through other people’s eyes, and it’s been a real eye-opener for him.” For the most part, she says, he’s happy. “Out of the clear-blue sky, he’ll be in the kitchen and say, ‘You know, Mom, I love you.’ He’d never said that in his life.”

He has also developed a sense of empathy. Now, when a child at his school acts up in a way that he might have done in the past, he tells his brother, “‘I owe you and Mom an apology,’” Sally says. “He’s seen it through other people’s eyes, and it’s been a real eye-opener for him.” For the most part, she says, he’s happy. “Out of the clear-blue sky, he’ll be in the kitchen and say, ‘You know, Mom, I love you.’ He’d never said that in his life.”

When new symptoms pop up, the temptation to switch medications can be hard to resist, especially because a complex prescription history can condition families to look to drugs first. But sometimes the solution is far simpler.

This past fall, Phoenix began falling asleep in class in the middle of the day. One of his earlier medications had had a similar effect — making him so drowsy he once fell asleep in the middle of lunch at a busy restaurant — so Sally was concerned. Was he falling asleep because he was crashing as a stimulant wore off? Or because a medication was suddenly causing a new side effect? The last thing she wanted to do was to tweak his finely tuned regimen.

Before taking him in for an assessment, she did a bit of sleuthing. “I bought a Disney Circle,” she says. “Best $100 I ever spent in my life.” The device monitors, and sets limits on, their home Wi-Fi network. It revealed that Phoenix had been getting up in the middle of the night and playing with electronics for hours. She set it to restrict overnight internet access — and suddenly Phoenix was staying awake through school again.

“It’s not uncommon for kids to be on more than one medication. The question is: Is it people fumbling around to try a little of this and a little of that and see if it works — or is it rational?” asks Lawrence Scahill, director of clinical trials at the Marcus Autism Center of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. When medication decisions are made judiciously and each one has a clear target, drug combinations can have a clear benefit. Under those circumstances, Scahill says, “I would say that there is such a thing as rational polypharmacy.”

Phoenix’s path, as winding as it has been, has brought him to a good place. He is an example of how polypharmacy, when attempted with attention, care and persistence, can provide people with autism the opportunity to thrive.

He is an example of how polypharmacy, when attempted with attention, care and persistence, can provide people with autism the opportunity to thrive.

But finding and maintaining the right treatment regimen is still up to each physician, each family, each individual. “This is an experiment that’s going on, but it’s a completely uncontrolled experiment,” Scahill says. Ben, Phoenix, Connor: Each of them confronted different challenges and had to figure his own way through, because prescribing is still very much an art, not a science. Clear rules will be a long time coming, if they arrive at all.

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

TAGS: ADHD, adults with autism, antidepressants, anxiety, attention, autism, bipolar disorder, depression, risperidone, treatments, valproic acid

Drug load is a problem for people with autism

06/09/17

Many children and adults with autism take many drugs at the same time, which can lead to serious side effects and may not even be effective

Source: Spectrum News

Connor was diagnosed with autism early at the age of 18 months. Even at that age, his condition was obvious. “He would arrange things in rows, turn lights on and off non-stop,” says his mom, Melissa. He was bright, but did not speak until he was 3 years old and quickly lost his temper. When he went to school, he couldn't sit at his desk, shouted out answers without raising his hand, and freaked out when he didn't understand something in math or couldn't write by hand at the same speed as everyone else. “One day he wrapped himself in a carpet like a roll and refused to come out until I arrived at school,” recalls Melissa. nine0003

Even at that age, his condition was obvious. “He would arrange things in rows, turn lights on and off non-stop,” says his mom, Melissa. He was bright, but did not speak until he was 3 years old and quickly lost his temper. When he went to school, he couldn't sit at his desk, shouted out answers without raising his hand, and freaked out when he didn't understand something in math or couldn't write by hand at the same speed as everyone else. “One day he wrapped himself in a carpet like a roll and refused to come out until I arrived at school,” recalls Melissa. nine0003

Connor was prescribed his first psychiatric drug, methylphenidrate (Ritalin), when he was 6 years old. The drug did not last long, but at the age of 7, the parents tried again. The psychiatrist suggested a low dose of dextroamphetamine (Adderall), a psychostimulant used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The drug markedly improved his behavior at school: now he could sit at his desk longer and follow what the teachers were saying. His handwriting "like a chicken's paw" became legible. Then his handwriting became neat. Then perfect. And then he became the subject of Connor's obsession. nine0003

His handwriting "like a chicken's paw" became legible. Then his handwriting became neat. Then perfect. And then he became the subject of Connor's obsession. nine0003

“We were told that there would always be pros and cons. The drug helped him get through a day of school and we thought it was worth it,” says Melissa. And he was worth it. Some time.

But when Adderall's action ended at the end of the day, Connor felt worse than ever. During the day he wept and refused to do anything. Because of the psychostimulant, it became difficult for him to fall asleep in the evening. So after a month or two, the psychiatrist added a second drug, guanfacine (Intuniv), to treat ADHD, anxiety, and hypertension, which can also reduce insomnia. The psychiatrist hoped this would ease Connor's daytime and help him sleep. nine0003

In a sense, the effect was the opposite. During the day he began to feel better, but Connor developed very severe mood swings and was so irritated every evening that he was very difficult to deal with. And now, instead of just tossing and turning in bed, he began to categorically refuse to go to bed. “He didn’t go to bed because he was always angry about something,” says Melissa. “He worked himself up and couldn’t stop, every night he got upset and started crying.” nine0003

And now, instead of just tossing and turning in bed, he began to categorically refuse to go to bed. “He didn’t go to bed because he was always angry about something,” says Melissa. “He worked himself up and couldn’t stop, every night he got upset and started crying.” nine0003

Seven months later, the parents said that it was simply impossible to continue taking this combination. They replaced guanfacine with over-the-counter melatonin, which helped Connor sleep better without any visible side effects. However, a year later, he developed a tolerance for Adderall. Connor's psychiatrist increased the dosage, and this, in turn, led to the development of tics: Connor began to jerk his head and sniffle. During a medical examination at the age of 9, the doctor noticed that over the past two years he had hardly grown. His weight had not changed at all since the age of 7, and now he was much lower than normal. nine0003

This is where the drug experiments stopped. The parents removed the child from all prescription drugs, and today, at almost 13 years old, Connor still does not take any medication. His tics are almost gone. Although he still struggles to concentrate in class, his mom thinks the risks outweigh the benefits, and she's against new drugs. “If we can somehow manage without drugs, then we will manage without them.”

His tics are almost gone. Although he still struggles to concentrate in class, his mom thinks the risks outweigh the benefits, and she's against new drugs. “If we can somehow manage without drugs, then we will manage without them.”

Connor is just one of many, many children with autism who are being prescribed multiple drugs at the same time. Phoenix started taking risperidone (Risperdal) at just 4 years old. This drug has been approved for the treatment of irritability in autism. He is now 15 years old and has experience with over ten different psychiatric medications. Ben is 34 and has autism but has been misdiagnosed with other disorders in the past. He was in middle school when his mother insisted that he start taking drugs for depression and behavioral problems. The doctor tried one antidepressant after another, but nothing worked. In high school, at age 15, he was misdiagnosed as having bipolar affective disorder and was prescribed an anticonvulsant drug and an antidepressant. nine0003

nine0003

It is not uncommon for children with autism to take two, three, or even four drugs at the same time. The same is true for many adults with autism. There are not enough statistics on this subject, but the limited information currently available suggests that adults with autism are even more likely to be prescribed multiple drugs than children.

Specialists are particularly concerned about prescribing psychiatric drugs to children because such drugs can have unwanted effects on brain development and are rarely tested on children. nine0003

In general, polypharmacy—taking more than one drug at the same time—is very common among people with autism. One study found that among 33,000 people with autism under the age of 21, at least 35% were taking two psychotropic drugs at the same time, and 15% were taking three drugs.

“Psychotropic drugs are so commonly prescribed for people with autism because there are few treatment options,” says Lisa Kroen, director of the Autism Research Program at Kaiser Permanente in California. - Is such a drug load bad? This question is difficult to answer. We just don't know - no research has been done." nine0003

- Is such a drug load bad? This question is difficult to answer. We just don't know - no research has been done." nine0003

Sometimes, as in Connor's case, a second drug is given to treat side effects of the first. Most often, doctors prescribe drugs for each individual symptom - a psychostimulant for concentration, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for depression, an antipsychotic for aggression, and so on. (Children with autism who also have epilepsy take anticonvulsant drugs. But since such drugs are effective and available, they are usually not considered part of the polypharmacy problem.) nine0003

“Kids come to me on Zoloft, Depakota and risperidone,” says Matthew Siegel, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. Zoloft is an antidepressant, Depakot is a mood stabilizer, and risperidone is an antipsychotic. Three psychotropic drugs per patient.”

In other cases, due to moves, changes in insurance, or dissatisfaction with treatment, people on the spectrum end up with many different doctors, each with their own opinion, who may add a new drug but not remove the old one. nine0003

nine0003

Why is there such confusion? Because there is no single drug for the treatment of autism itself.

There are so-called key characteristics of autism - repetitive behaviors, difficulties with social interaction and impaired communication. Behavioral therapy can help with these three characteristics, but no drug can change them. Those drugs that are prescribed to people with autism are the treatment of peripheral problems that greatly complicate life - ADHD, irritability, anxiety, aggression, self-aggression. nine0003

The current practice that leads people to take cocktails of psychotropic drugs can be ineffective and harmful. Each doctor decides for himself what will be effective and safe, because there are simply no studies. “We have so few single drug studies, so few studies comparing different drugs alone,” says Brian King, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. “We still have a lot to learn before we even get to research into different combinations of drugs. ” nine0003

” nine0003

Datura drug

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved only two drugs for children and adolescents with autism: risperidone and aripiprazole. Both are atypical antipsychotics and are prescribed to treat behavioral problems associated with increased irritability, for example, if a child has aggression, tantrums, and self-aggression. These drugs relieve such problems in about 30-50% of cases - they do not help the rest. nine0003

This is a huge gap: psychiatric problems are common in children with autism. A 2010 study found that 80% of children with autism who presented to a mental health center also had ADHD, 61% had at least two anxiety disorders, and 56% had clinical depression.

Multiple diagnoses lead to drug cocktails, but there are no clinical trials for drug combinations, so in most cases it is not known how different psychotropic drugs interact with each other. "Each drug has its own side effects, and when you prescribe a mixture of them, you are effectively prescribing a new drug that has not been studied," says King. “And if we are talking about autism, when there can be severe communication disorders, then the risks are even greater, because it is difficult for patients to tell you that they feel bad from your drugs.” nine0003

“And if we are talking about autism, when there can be severe communication disorders, then the risks are even greater, because it is difficult for patients to tell you that they feel bad from your drugs.” nine0003

What's more, researchers say these drugs may not work at all for people with autism.

“Many studies have examined the use of drugs to treat ADHD in people with autism. The same is true for drugs to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder and repetitive behaviors, says Daniel Couri, a pediatrician at the National Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. “And virtually all of these studies have shown that these drugs are much less effective for people with autism than for people without autism.” nine0003

These studies are relatively rare and were mostly uncontrolled. In 2013, a meta-analysis of existing studies found that most studies of psychiatric drugs for autism are either too small or poorly designed to tell if the drugs are effective. The existing data, the researchers write, “can only be considered speculation that needs to be evaluated in well-controlled studies. ”

”

The symptoms of depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD and other psychiatric conditions seem to be the same in people with and without autism. But the causes of autism are very different, which means that the biochemical processes behind them can differ and vary from person to person. nine0003

"It's a huge problem with treating autism in general," Siegel says. Autism is caused by so many genetic variations that the condition of each individual can be unique, which means that treatment must be individualized. Even in ideal conditions of clinical trials, the drug can only help 20% of people. The antipsychotics aripiprazole and risperidone stand out because they can be as effective as 50%. “50% is like a record in this area,” Siegel says. nine0003

Paradoxically, another reason children and adults with autism may be given different drugs, as in the case of Connor, is that doctors use the second drug to reduce the side effects of the first. Antipsychotics, for example, can lead to weight gain and metabolic disorders, as well as involuntary muscle contractions. Some doctors add metformin for weight gain and benztropine (Cogentin) to relieve involuntary movements.

Some doctors add metformin for weight gain and benztropine (Cogentin) to relieve involuntary movements.

But every new drug brings its own potential side effects. Metformin can cause muscle pain and, less commonly, anxiety and nervousness. Benztropine can lead to confusion and memory problems. Physicians with little experience in treating patients with autism may mistake side effects for new symptoms and prescribe new drugs in response. In the vast majority of cases, psychotropic drugs are prescribed by doctors with little or no experience with autism, Siegel says. "People just don't know what they're doing, so it's not surprising that kids end up taking multiple drugs." nine0003

Toxic Pills

As a preteen, Ben had problems typical of a child with autism: social anxiety, difficulty communicating with peers, mild depression, violent temper tantrums, inattention, and disruptive behavior in class. When he was 12 years old, school testing revealed he had sensory processing problems and dysgraphia (problems with handwriting), but not autism. At the mother's request, the doctor tried an antidepressant. It didn't help and only led to headaches. A new antidepressant followed, and then another. The side effects weren't worth taking, so Ben got a short break from his medication. nine0003

At the mother's request, the doctor tried an antidepressant. It didn't help and only led to headaches. A new antidepressant followed, and then another. The side effects weren't worth taking, so Ben got a short break from his medication. nine0003

Two years later, when he was 16 years old and his problems at school and at home were getting worse, his mother again insisted on medication. A new doctor prescribed a newly approved SSRI, citalopram (Celexa), recommending that Ben and his mother see a specialist. But for a year, life was too busy to look for a specialist, and Ben just took citalopram.

Over the next year, the situation at the school got worse and worse. Ben was bullied more and more often by his classmates, he increasingly responded to them with aggression, so his mother finally took him to a psychotherapist. He diagnosed Ben with bipolar affective disorder and referred him to a psychiatrist with a recommendation to add valproic acid (Depakote) to his drugs. Ben recalls that the psychiatrist asked him a couple of questions, and then simply gave him a prescription for the two drugs that the therapist asked for. Ben's autism was never diagnosed. nine0003

Ben's autism was never diagnosed. nine0003

“That's when things really changed,” says Ben. He gained a lot of weight. He couldn't concentrate in class. He made scenes at school and at home, his anxiety reached a new peak. “My behavior has become more aggressive and unpredictable,” he says. In the middle of the night, he would wake up terrified, and then just walk in circles around the room. “I don’t think that such an escalation would have happened without drugs,” he said. He started fighting with his father. “I fell into complete despair, sobbed, I could punch a hole in the wall with my fist.” nine0003

Five drugs and five psychiatrists later, Ben became lethargic, irritable, angry and unable to concentrate on anything.

Finding a combination of drugs is especially difficult if the attending physician changes all the time. In Ben's case, not only was he misdiagnosed, but the family moved twice. In addition, his psychotherapist and psychiatrist did not discuss his diagnosis and treatment with each other. In other cases, people may not have access to doctors who understand autism. Some people change doctors hoping to find an approach they like, or are forced to do so because of insurance changes. The list of drugs is growing due to "the lack of one person responsible for the entire treatment process," says Shafali Jeste, a pediatric neurologist at the University of California, Los Angeles: "In our city, this happens all the time." nine0003

In other cases, people may not have access to doctors who understand autism. Some people change doctors hoping to find an approach they like, or are forced to do so because of insurance changes. The list of drugs is growing due to "the lack of one person responsible for the entire treatment process," says Shafali Jeste, a pediatric neurologist at the University of California, Los Angeles: "In our city, this happens all the time." nine0003

The stack of prescriptions may become thicker as the child transitions from adolescence to adulthood.

"People who are prescribed drugs often stay on them for long periods of time and don't even try to determine if they still need them," says David Posey, a psychiatrist in Indianapolis, Indiana. It is usually recommended to review the drug regimen at least once a year, to evaluate the possibility of reducing the dosage, but this is not always possible. "If the drug worked, families might be against trying to take it off." nine0003

Jeste says that her clinic is often visited by people with a long list of drugs, but without a well-formed medical record and anamnesis, and it is sometimes impossible for her and her colleagues to understand why a particular drug was ever prescribed and whether it helps. In these cases, she gradually reduces the dosage of one drug after another.

In these cases, she gradually reduces the dosage of one drug after another.

Ben was not lucky enough to find such a specialist. By the end of his last year at school, he fell asleep in class and felt so bad that he dropped out. “Then my parents were getting divorced,” Ben recalls that time. “There was complete chaos around, I was losing all my support, I was losing my usual daily routine, I started sleeping in the car.” nine0003

He started smoking marijuana, which he said made him euphoric when combined with antidepressants. But at the same time, she helped him function. “It helped me connect with people better than drugs,” he says. Ben says marijuana helped him better understand how psychiatric drugs work on him, and that they cause the same mood swings, just much more slowly. "I had the idea that maybe the mood cycles I often experience coincide with the drug use." nine0003

At the age of 21, he made the decision to get rid of both illegal drugs and prescription drugs. A year later, he was diagnosed with autism. Now he has learned to step aside and take deep breaths every time he feels a fit of anger coming on. No more holes in the wall. He goes for a run six times a week, and physical activity helps him stay calm, clear and focused. Autism may have been responsible for the initial mood swings and aggression, but he says the drugs are a vicious circle. nine0022

A year later, he was diagnosed with autism. Now he has learned to step aside and take deep breaths every time he feels a fit of anger coming on. No more holes in the wall. He goes for a run six times a week, and physical activity helps him stay calm, clear and focused. Autism may have been responsible for the initial mood swings and aggression, but he says the drugs are a vicious circle. nine0022

Treatment

Multiple medications are not always a bad thing. Some children have very serious problems in their lives, their behavior can pose a serious threat to themselves and others, and in these cases, medication may be the only way out.

Phoenix was one of those children. “He was a little tornado,” his mom says. One day in early 2007, she received a call from the kindergarten asking her to pick him up early because he was being very aggressive, knocking over tables and chairs for no apparent reason. He escaped twice that day - once he jumped out of the car on the way home, then climbed out of the bedroom window. The police found him in the middle of a busy highway. He was only four years old. nine0003

The police found him in the middle of a busy highway. He was only four years old. nine0003

Sally, Phoenix's mother, says he has always been a difficult child. But when his mood swings escalated into aggression, he could lash out at people and try to harm his older brother, who also had autism. “He was strong beyond his years,” she says. She knew that at all costs she must help him deal with his anger, for the safety of both boys.

His doctor tried risperidone, then added guanfacine and Adderall. However, this did not affect his aggression. Sally recalls that every morning she and her husband woke up, looked at each other and said: “How is Phoenix now?” After that, "everything inside her froze." It was obvious that drugs needed to be selected, but the family could not cope with him at home. When Phoenix was 6 years old, he was first admitted to the hospital. nine0003

By 2009, his clinic had already changed psychiatrists twice. The new psychiatrist replaced Adderall with Vyvans. A blood test then showed that Phoenix had an increased risk of developing breasts, a serious but rare side effect of risperidone called gynecomastia. The psychiatrist changed risperidone to Seroquel. “It was a disaster,” Sally says. Phoenix climbed out of the windows, got up and walked around the classroom, attacked his brother for no reason. None of the drug combinations alleviated the aggression and mood swings. Aude

A blood test then showed that Phoenix had an increased risk of developing breasts, a serious but rare side effect of risperidone called gynecomastia. The psychiatrist changed risperidone to Seroquel. “It was a disaster,” Sally says. Phoenix climbed out of the windows, got up and walked around the classroom, attacked his brother for no reason. None of the drug combinations alleviated the aggression and mood swings. Aude

The case shocked the whole family and ended with a new hospitalization and a new drug combination. The doctors replaced Seroquel with another neuroleptic, Geodon, and also prescribed valproic acid and guanfacine. Since Phoenix's brother, Mack, was greatly helped by Strattera's anti-ADHD drug, the hospital staff replaced Vyvans with Strattera.

Phoenix has been in four different inpatient programs, been hospitalized six times, tried more than a dozen drugs, sometimes four at a time. Hospitalizations helped to take him off certain drugs and gradually introduce others that, at least temporarily, controlled his mood swings. But every time after he was discharged, the drug combinations stopped working and he returned to aggression, mostly against his brother. The first two stationary programs did not help at all. They created stability and structure in his life: every day was the same, the daily routine was very reliable. But the programs could not adjust the drug regimen. And when he returned home, where such a tough regime no longer existed, he began to attack his brother. "We've had holes in our doors from the time Phoenix tried to get to Mac," she says. nine0003

But every time after he was discharged, the drug combinations stopped working and he returned to aggression, mostly against his brother. The first two stationary programs did not help at all. They created stability and structure in his life: every day was the same, the daily routine was very reliable. But the programs could not adjust the drug regimen. And when he returned home, where such a tough regime no longer existed, he began to attack his brother. "We've had holes in our doors from the time Phoenix tried to get to Mac," she says. nine0003

The next two programs focused on children with autism, and they provided the necessary assistance to Phoenix. He was 12 when he entered the third program and began taking an antipsychotic commonly prescribed for bipolar disorder, olanzapine (Zyprexa). And in the fourth inpatient program, when he was 13 years old, doctors found what seemed to be the perfect combination: olanzapine, valproic acid, guanfacine and atomoxetine. He spent weekends at home, but lived at a nearby facility for a week, where he also received behavioral therapy and social adjustment support. “For the first time when he came home, we really enjoyed his company, we were able to see what a real Phoenix is,” says Sally. nine0003

“For the first time when he came home, we really enjoyed his company, we were able to see what a real Phoenix is,” says Sally. nine0003

But a common side effect of Zyprexa is weight gain, and the drug made Phoenix constantly hungry. “On weekends, he emptied the refrigerator at three in the morning,” she says. The overly thin boy began to suffer from obesity. “He looked like a balloon about to burst,” his mother says. He was sitting and he was short of breath. We had to take it off the Zyprexa."

His doctor took him off Zyprexa and put him on another antipsychotic and then another (Seroquel) until the combination started to work. nine0003

Phoenix is now 15 years old, on four drugs and has been stable for over a year. His mood is also stable. “The aggression is gone,” Sally says. He developed a sense of humor and started watching TV with his family and discussing what he saw with them. He also began to develop the capacity for empathy. Now, if he sees that a child at school is behaving the same way as he once did, he says to his brother: "I must apologize to you and mom. " According to Sally: “He saw himself from the outside, and it affected him very much. One day, for no reason, he came into the kitchen and said: "You know, mom, I love you." He never said that." nine0003

" According to Sally: “He saw himself from the outside, and it affected him very much. One day, for no reason, he came into the kitchen and said: "You know, mom, I love you." He never said that." nine0003

When new symptoms appear, the temptation to change medications can be very strong, especially with a difficult treatment history where parents are used to thinking about the drug approach first. But very often new problems can be solved with simple methods.

This fall, Phoenix began to fall asleep in class during the day. One of the previous drugs had had the same effect on him - he was so sleepy that he could fall asleep even during lunch in a noisy restaurant. Sally was very worried. She was afraid that this meant that the effect of the psychostimulant was ending, or this was some new side effect. She did not want to change the already established treatment regimen. nine0003

Before taking him to the doctor, she decided to investigate. She bought a device to restrict and monitor her home Wi-Fi network. It turned out that Phoenix got up at night and spent hours playing on the computer. She started turning off the Internet at night, and Phoenix immediately became alert during the school day.

It turned out that Phoenix got up at night and spent hours playing on the computer. She started turning off the Internet at night, and Phoenix immediately became alert during the school day.

“It's not uncommon for children to take more than one drug. The question is: do people just try everything in the hope that it will help, or is there some kind of rational justification? says Lawrence Scahill, director of clinical trials at the Marcus Autism Center at Emory University. When treatment decisions are made carefully and with a very clear goal in mind, drug combinations can be very helpful. Under these circumstances, Scahill believes, "we can talk about the so-called rational polypharmacy." nine0003

The path of the Phoenix, although very thorny, led him to favorable results. This is an example of how polypharmacy, with care, attention and perseverance, can help people with autism live fulfilling lives.

However, the decision to take drugs always depends on the individual doctor, individual family, individual person. "Every time it's an experiment, but it's not a controlled experiment," Scahill says. Ben, Phoenix and Connor: Each of them faced different problems with no ready-made solutions, because prescribing drugs for autism is still more art than science. There are still no clear rules, and one can only hope that they will nevertheless appear. nine0003

"Every time it's an experiment, but it's not a controlled experiment," Scahill says. Ben, Phoenix and Connor: Each of them faced different problems with no ready-made solutions, because prescribing drugs for autism is still more art than science. There are still no clear rules, and one can only hope that they will nevertheless appear. nine0003

See also:

Does a child with autism need to take medication?

Autism treatment - present and future

Autism and mental health

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Methods and treatment, Psychiatry

Autism. The best medicine is love

2 April 2019

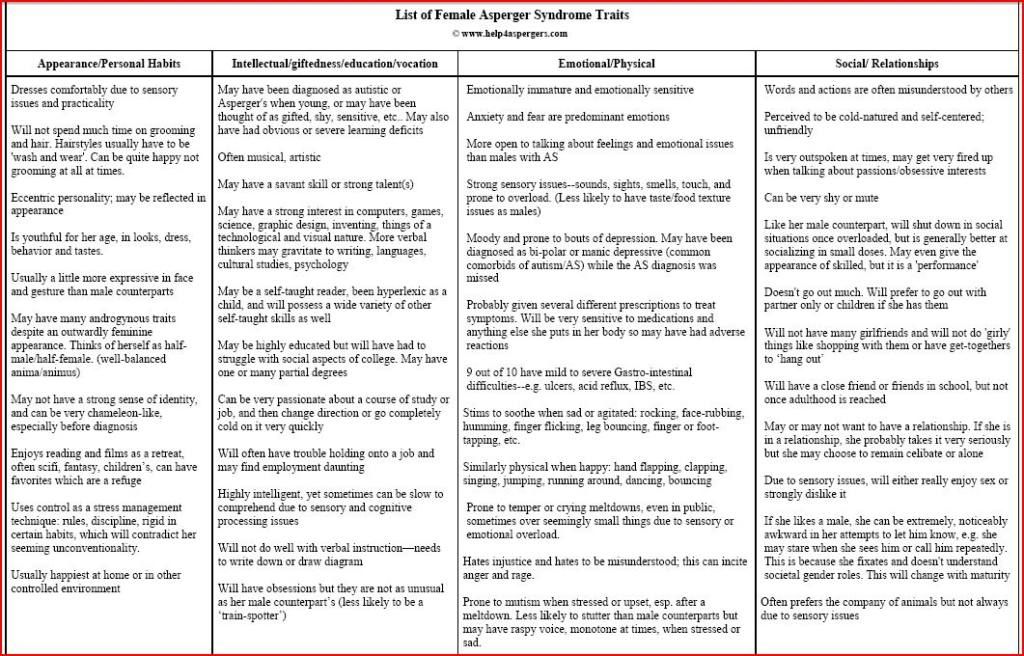

Autism is a disease that occurs due to a malfunction of the brain. In general, there are several types of autistic disorders, such as Asperger's syndrome, but the main characteristic of all types is the difficulty of interacting with society. Until now, science does not know the causes of autism in children, so it is possible to understand exactly why a child was born this way only in 15% of cases, and the number of such children is approximately 10 people per 10,000. And, according to statistics, most often among understandable causes appear precisely genes. nine0003

Until now, science does not know the causes of autism in children, so it is possible to understand exactly why a child was born this way only in 15% of cases, and the number of such children is approximately 10 people per 10,000. And, according to statistics, most often among understandable causes appear precisely genes. nine0003

Autistic people are born mainly in those families in which parents or other relatives suffer from autism or its various manifestations, such as depression. By the way, this includes not only unreasonable long-term longing, but also paranoia, alcohol binges, drug addiction or vegetative-vascular disorders. Those parents whose relatives do not really like to be in society, and prefer solitary activities to communicate, should be wary.

In general, every family has a desire to reduce the risk of autism in a baby, so scientists have been researching this issue for a long time and trying to find universal ways to protect children from this disease even at the stage of pregnancy. To begin with, even before conception, it is necessary to fully prepare your body for pregnancy, this also applies to future fathers, but for the most part it is necessary for expectant mothers to prepare, and it is desirable that preparation begin six months before pregnancy. For example, switch to proper nutrition, adjust your daily routine, get enough sleep to reduce stress levels, increase the functioning of the immune system, take the necessary vitamins and, of course, fully check your body with specialists. In principle, these recommendations should also be followed during pregnancy. It is important to keep positive emotions, do not expose yourself to stress, eat well, see a doctor and not take any medication without consulting a specialist. nine0003

To begin with, even before conception, it is necessary to fully prepare your body for pregnancy, this also applies to future fathers, but for the most part it is necessary for expectant mothers to prepare, and it is desirable that preparation begin six months before pregnancy. For example, switch to proper nutrition, adjust your daily routine, get enough sleep to reduce stress levels, increase the functioning of the immune system, take the necessary vitamins and, of course, fully check your body with specialists. In principle, these recommendations should also be followed during pregnancy. It is important to keep positive emotions, do not expose yourself to stress, eat well, see a doctor and not take any medication without consulting a specialist. nine0003

It is possible to recognize autism in a child from an early age. There are several signs of autism in children. Firstly, the baby does not give any reaction to the speech of people, for example, does not turn his head in the direction from which the voice sounds. Secondly, after a year of life, he does not gesticulate in any way, for example, he does not point his finger at the object he needs. Thirdly, if he forgot how to do something that he had already done before, for example, he stopped talking. Some begin to convince parents that this is normal, that the child will later outgrow this condition and catch up with his peers in development. nine0003

Secondly, after a year of life, he does not gesticulate in any way, for example, he does not point his finger at the object he needs. Thirdly, if he forgot how to do something that he had already done before, for example, he stopped talking. Some begin to convince parents that this is normal, that the child will later outgrow this condition and catch up with his peers in development. nine0003

In fact, without the help of parents and specialists, his condition can only worsen.

Many mothers say that their children did not look people in the eye, they were afraid of any noise, they played sitting in the corner. In addition, the games were monotonous movements, for example, rolling a car back and forth. It is worth realizing that autism significantly interferes with the development of the child, and not just limits him in communication, therefore, such signs should never be ignored. Of course, you can read some manual on the treatment of autism in children, but the main advice from me will be the same - if you notice the above signs in your child, contact a specialist, only he can really competently help your child and professionally advise you.