Working with trauma

6 Skills-Your Trauma Toolkit — Integrative Psychotherapy Mental Health Blog

Trauma is comparable to an inner shattering. shattering of safety.

Shattering of beliefs.

Shattering of identity.

Or, shattering of a role in life.

You world has changed, and often you are changed, forever.

If you are a trauma survivor, you have the brave yet powerful job to rebuild. Rebuild yourself, your life and a new sense of hope and meaning.

You reach out for therapy because research proves that good therapy will help you. Which it does.

However, trauma work goes beyond the walls of your warm, wise and skillful therapists office. You have your life before you walk into your therapy session, and your reality is with you as you walk out into the world, the world that you live in.

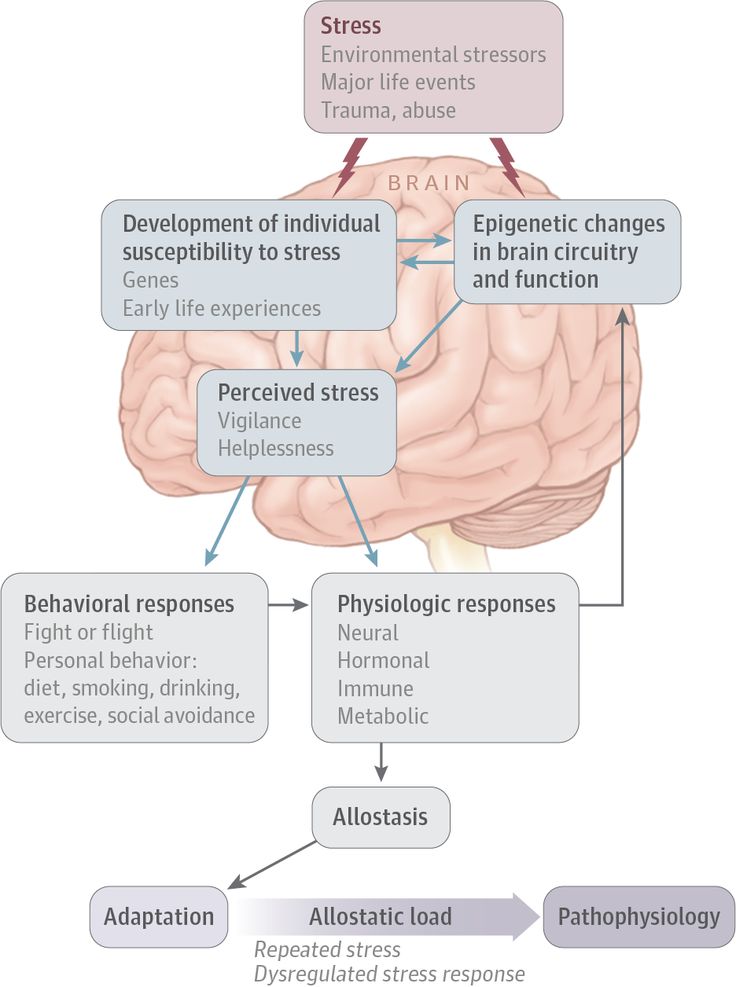

Your brain keeps working through the traumatic material you've processed in session. Processing is the brains way of attempting to heal, however, when something distressing happens the brain may experience flashbacks, nightmares or body memories after a frightening experience.

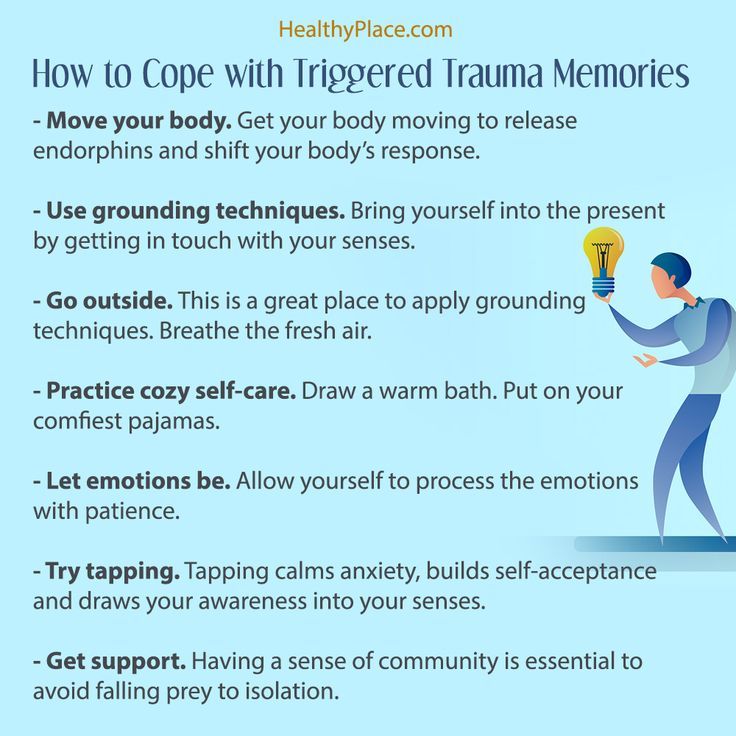

Because of this, it's important to have effective coping skills at your fingertips that you can use between sessions. Here are some six coping skills that can be used to support you, both in and out of session while you're engaged in trauma therapy.

1. Body ScanA body scan is an exercise where you bring attention to your body, while not trying to change anything you may notice. The goal is not specifically for you to relax, it is simply about raising awareness about what is happening in the present moment.

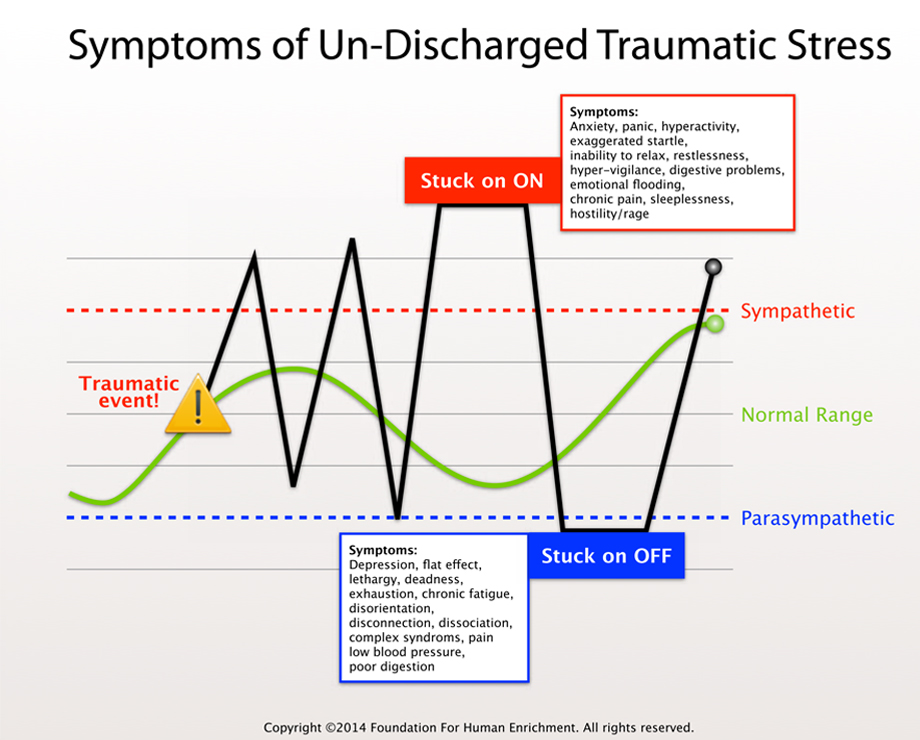

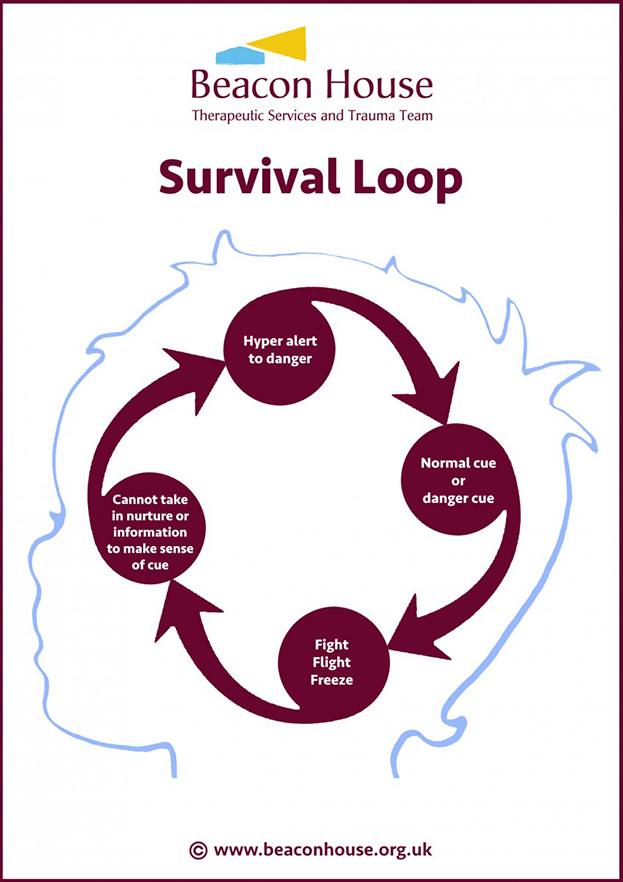

The body often experiences continued trauma symptoms, even long after the traumatic event has passed. Trauma responses include the body preparing to go into flight, fight or freeze, tensing the body, which takes an exhausting toll on you.

It might sound funny that this exercise isn't about changing anything, yet sometimes just noticing the tightness or the sensation is enough. When your body is already in stress mode, adding another "to do" often gets you trapped, so being able to engage in a mindful exercise is often the best option (Shapiro, 2001).

You start the body scan by either focusing on the top of your head, forehead, ears, cheeks, neck, and go down to each section of the body, or you can start from you hands or feet and slowly pay attention to other areas, noticing any tingling or sensations that come up. There's no wrong way to do the exercise.You might notice an itch, tightness, discomfort or you might not feel anything that all. Just notice. Breath through it and you've done the scan!

2.Safety SwitchesSafety switches are physical techniques that use different body senses to help you cope with difficult feelings. Experiment with different techniques until you find a specific posture, stance or even eye gaze that brings you back to a place of strength, a feeling of "grounded-ness" or in touch with your inner wisdom.

You can try to sit up, square your shoulders, and open your posture, maintaining a boundary between yourself and whatever you are facing. You can also try gently turning your lips up to something that is called "Half Smile".

Just turning the edges of your lips upwards sends a neurological shift to the brain and releases feel-good-hormones, tricking your brain into thinking you are actually happy, or have something to smile about. Try it, it may offer even just a subtle shift (Linehan, 2015).

3. Cope AheadCoping ahead is a skill to use when you are worried about how you might feel, react or respond to a specific situation or event that is coming up.

What you do is to slowly imagine the exact scenario or situation, what difficulties you may have, including any urges, emotions or fears that you may experience. You then imagine what skill, belief or action plan you may need in order to get through.

For example, if you are going to visit a place where something traumatic happened, or even if you associate a location with something more subtle like it simply being a reminder to a time in your life that was hard or where you were ignored when you needed to be seen, imagine what it may be like to visit that place. Imagine practicing a mantra, checking in with a loved one or making sure to take breaks to see how you're doing, keeping yourself back from flooding into emotions that can override the present day experience.

Imagine practicing a mantra, checking in with a loved one or making sure to take breaks to see how you're doing, keeping yourself back from flooding into emotions that can override the present day experience.

Rehearse what you can do and say in any specific scenario. Doing this lets your brain use this as a quicker 'go-to' when stressed because you had practiced in advance (Linehan, 2015).

3. ContainmentContainment is a skill that is foundational to beginning any kind of trauma work, as it is effective in utilizing the brain's natural ability to hold and "contain" material.

Containment requires the use of imagery, creating some kind of container that can hold upsetting material until you are steady and able to properly process it. You begin this exercise by imagining a container such as a box, a vault, a safe, a trunk, a storehouse or the like. The container should have a lid or a door that can be opened and closed by you, and it also needs to be big, deep and strong enough to hold whatever it is that is causing distress.

You practice using the container first with something of lesser stress, and see if your brain can imagine gently sweeping, scooping or placing the information, thoughts, feelings and worries into the container until it can be addressed.

Practicing with less distressing information gives you information on what you may need to add. Do you need a lock, chains, or do you need windows, and a copy of a key to share with a loved one? A thermometer or timer that tells you when to take a break? You can take time finding the right "container" for yourself.

To be clear, this exercise is not about shoving away or ignoring information that is important.

Rather, it's a method to allow the brain to set aside information when there are trauma symptoms that are becoming overwhelming such a s thoughts, images and memories.

In session with my patients, we practice this and use ways to take a sliver at a time, eventually processing all that is important and necessary to be processed so that you can feel relief and reduction in the intense symptoms. Containment is an original skill that I learned in my earlier years of training in EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) which is a wonderful, scientific-based tool that helps the brain process trauma memories (Shapiro, 2001).

Containment is an original skill that I learned in my earlier years of training in EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) which is a wonderful, scientific-based tool that helps the brain process trauma memories (Shapiro, 2001).

When you begin noticing you are flooding or experiencing an overwhelmingly distressing feeling, use your senses and drop the memories or body sensations, rather throw yourself into doing the following.

Look around you and name 5 colors (green, red, yellow, blue, pink). Yes, say it out-loud, it helps.

5.5 sounds (car honking, baby crying, shuffling paper, A/C, phone buzzing)

5 things you can touch (my skin, my nails, the blanket, my purse, my tie)

5 things you can taste (a piece of gum, mint candy, sip of coffee/tea, chocolate chip, ice cube)

5 things you can smell. (scented candle, freshly baked goods, fresh laundry, scent of a flower, perfume,)

Distancing Technique

Distancing TechniqueSometimes the images won't go away, and in those instances you may want to use a distancing technique, which creates distance between your inner and outer world.

This stops the flooding as you become aware of where your body is, and brings you mind in the here-and-now, separating you from the memory or past event.

One way to do this is by putting the thoughts, memories or sensations on a conveyer belt and slowly watch the image, sound and thoughts fade, ever so slowly. You can also imagine putting whatever is coming up onto a TV screen and dimming the image so it gets smaller and smaller, or even just use an imaginal remote and switch the channel.

6. Body MovementBessel van der Kolk, one of the world's trauma experts has done extensive research that proves that our body is our most underutilized resource. His specific research is about body movement and PTSD, and how yoga has been found to drastically decrease symptoms related to trauma. Yoga slowly teaches trauma survivors to learn to tune in, feel themselves in their skin and begin to connect mind and body in a gentle fashion. Since trauma forces the mind and body to form a split to survive (often referred to as dissociation), using yoga is a great way to slowly bridge that gap, while also teaching the body how to feel emotions in a non threatening way (Van der Kolk, 2007).

Yoga slowly teaches trauma survivors to learn to tune in, feel themselves in their skin and begin to connect mind and body in a gentle fashion. Since trauma forces the mind and body to form a split to survive (often referred to as dissociation), using yoga is a great way to slowly bridge that gap, while also teaching the body how to feel emotions in a non threatening way (Van der Kolk, 2007).

If you're not up to doing yoga, I encourage you to even just integrate a practice of stretching, taking a short walk or engage in another form of movement.

Any kind of movement shifts things in the body and offers positive effects, such as biking, dancing, running, or even singing and slightly moving your body to the beat of the song. Find your own way to feel your body and lean on the inherent capabilities your body has to self nurture and sooth.

For today, give one of these skills a try.

And hey, try it even when you're not stressed, your brain may be more responsive, and receptive to giving it a go when you are in a trauma heated moment.

And if you live in New York and are ready to engage in one on one work to do the deep work to experience relief, we are here for you.

At Integrative Psych, our team of trauma and anxiety therapists are here to support you as you heal and move on with your life.

At our practice, we offer EMDR therapy, Somatic therapy, Attachment-Informed methods, Cognitive therapy, Internal Family Systems/Parts work and Expressive methods to help you experience relief.

And, get your some FREE downloadable worksheets and download to deepen your connection with yourself and engage in some mindfulness activities..and more. Click here for access to FREE content made with you in mind!

Click below to schedule your free 15 minute consult to see how we can map out a personalized plan to help you heal!

Blessings to you on your road to healing!

And if you’re a therapist and want our FREE Trauma Therapist Booklet, click here to download your copy!

Shapiro,R (2001): Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures, 2nd Edition Second Edition

Linehan, M (2015): DBT® Skills Training Manual, Second Edition Second Edition, Available separately: DBT Skills Training Handouts and Worksheets, Second Edition

Van der Kolk, B (2007):Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society 1st Edition

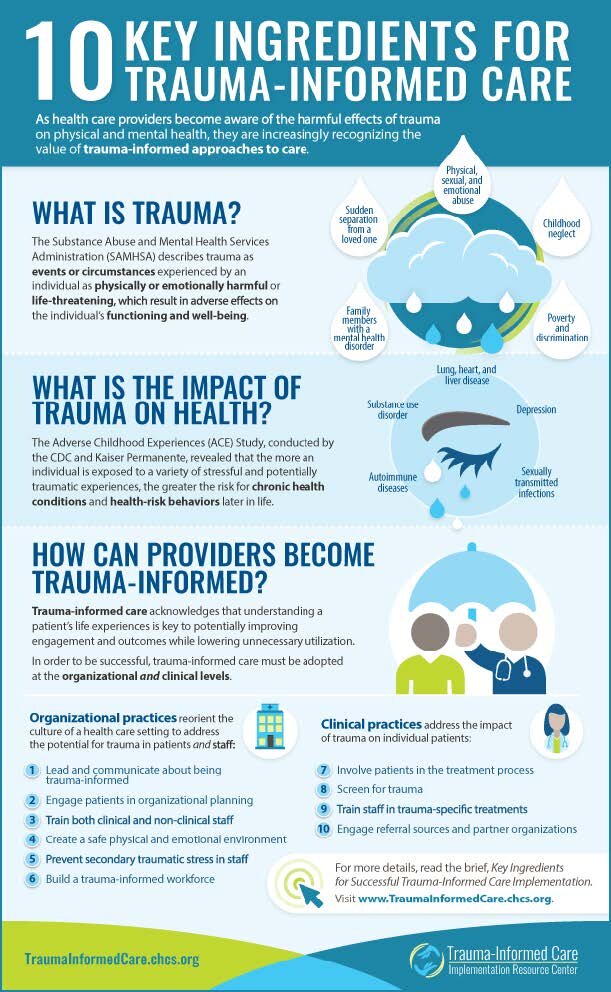

How to Support Clients Dealing With Trauma

Imagine going through a traumatic experience like a car accident, earthquake, or explosion.

That would be bad enough, wouldn’t it?

Now imagine reliving the experience, again and again, each day like a terrible nightmare. That really would be devastating, and it happens to many people around the world.

Unfortunately, some people who experience trauma develop post-traumatic stress disorder (van der Kolk, 2000). They need plenty of support and treatment when this happens.

You will learn more about post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), trauma, and the availability of treatments and resources in this article. Then you will be in a much better position to help your clients experiencing PTSD and trauma.

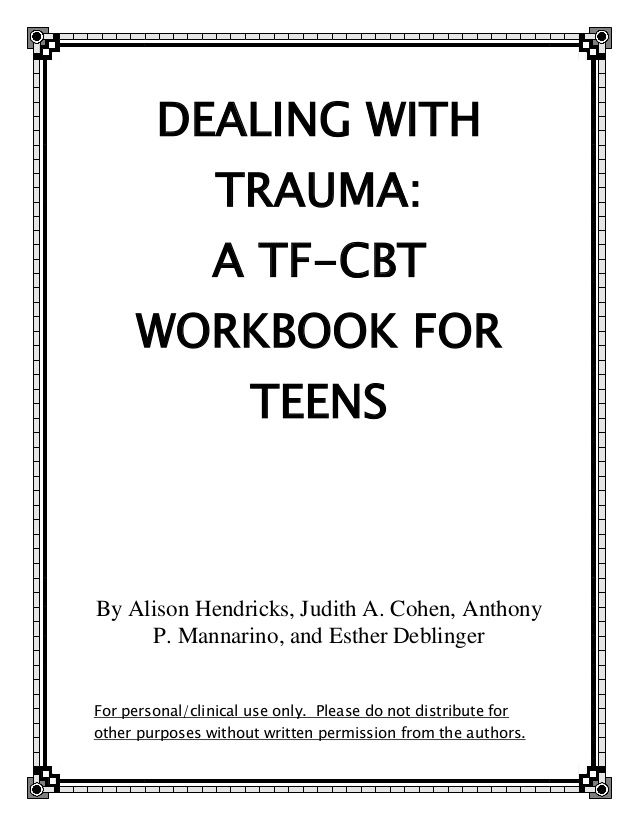

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will provide you with detailed insight into positive Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

- PTSD and Trauma: A Psychological Explanation

- 6 Possible PTSD Treatment Options and Paths

- How to Help Clients With PTSD and Trauma

- Using CBT to Heal Trauma: A Guide

- 2 Helpful Worksheets for Adults & Youth

- A Look at Trauma Psychoeducation: 2 Worksheets

- A Note on Group Therapy for Clients With PTSD

- Resources From PositivePsychology.

com

com - A Take-Home Message

- References

PTSD and Trauma: A Psychological Explanation

To understand this correlation, we start with a very brief history of PTSD.

1. Brief historical background

Historically, PTSD was known as ‘shell shock’ in World War I (Myers, 1915). Mention of the disorder first appeared in The Lancet, with soldiers documented as having various symptoms affecting their nervous system (Myers, 1915).

In World War II, it was referred to as ‘combat fatigue’ and believed to be related to long deployments (Marlowe, 2001).

2. Types of trauma

Trauma can be overwhelming for a person in psychological terms (Neria, Nandi, & Galea, 2008). A car accident, robbery, kidnap, torture, brutal attack, rape, witnessing death or a serious injury, war, and natural disaster can be classified as traumatic events (Kessler et al., 2014).

Traumatic events are quite common. By the age of 16, most people have experienced at least one traumatic event (Copeland, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, 2007). Psychological trauma, including onetime events, multiple occasions, and long-term repeated events, affects everyone differently (Bonanno, 2004).

Psychological trauma, including onetime events, multiple occasions, and long-term repeated events, affects everyone differently (Bonanno, 2004).

3. Relationship between PTSD and trauma

PTSD and trauma are closely related and often discussed relative to each other (van der Kolk, 2000).

Like other mental health conditions, PTSD does not discriminate between age, gender, ethnicity, or culture. Nevertheless, higher rates have been found in some populations (Beals et al., 2013) and lower rates in others (Creamer, Burgess, & McFarlane, 2001).

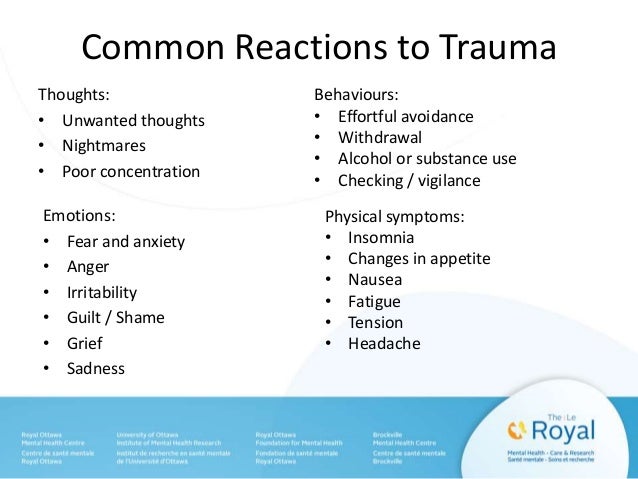

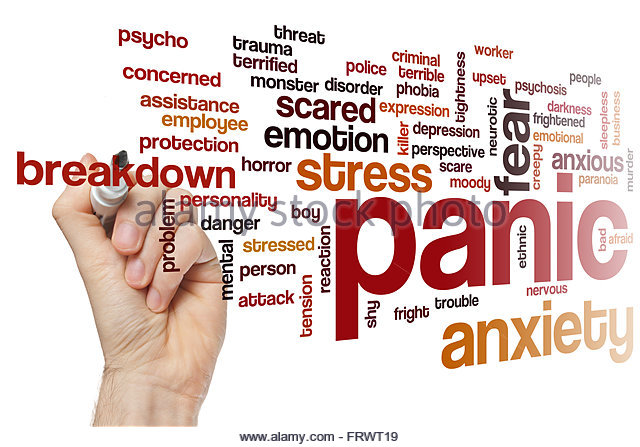

PTSD comes with a complex set of symptoms, including somatic, cognitive, affective, and behavioral, that are the effects of psychological trauma (van der Kolk, McFarlane, & Weisaeth, 1996).

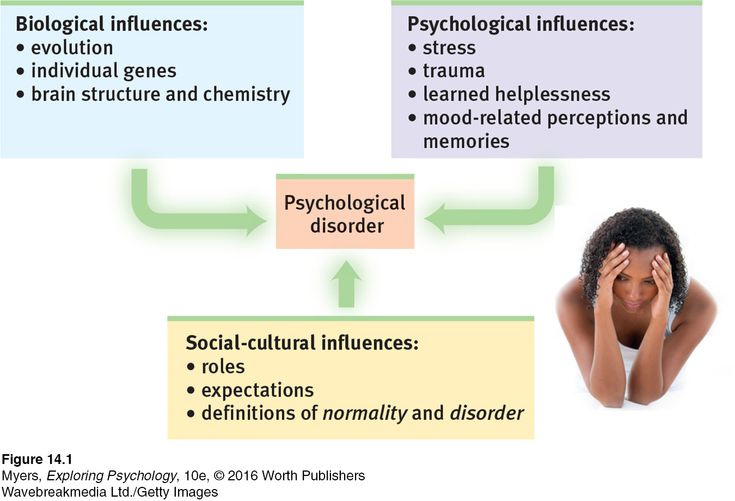

4. Etiology of PTSD

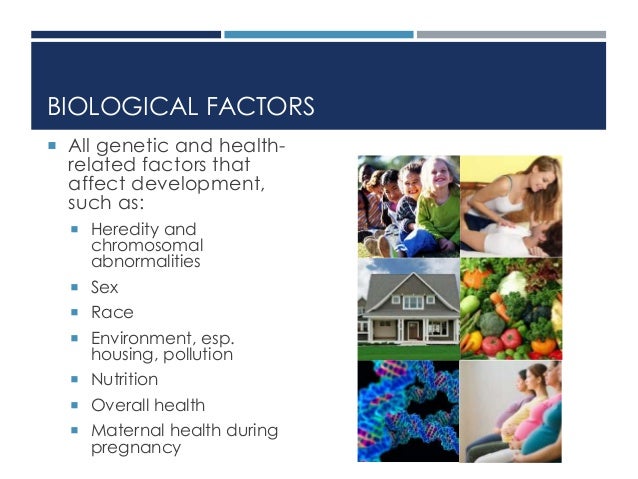

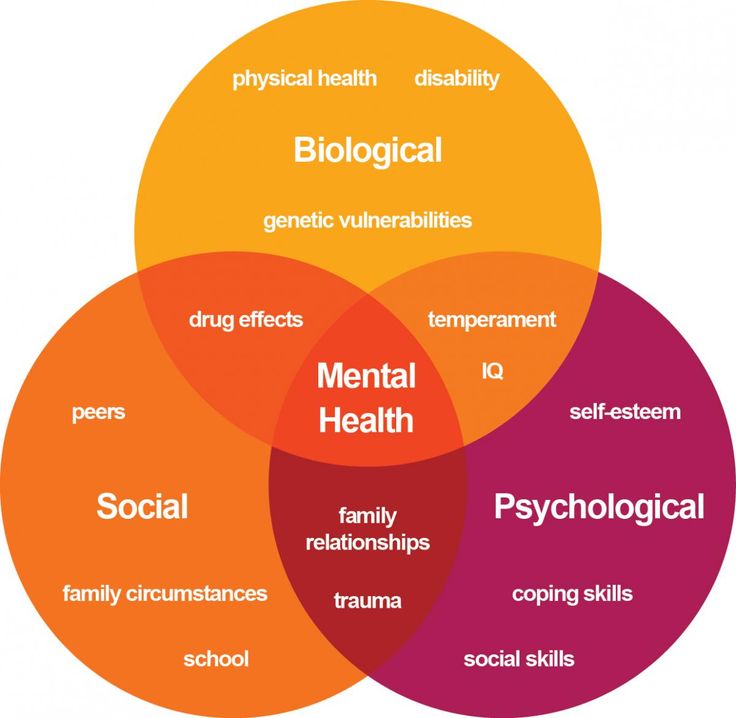

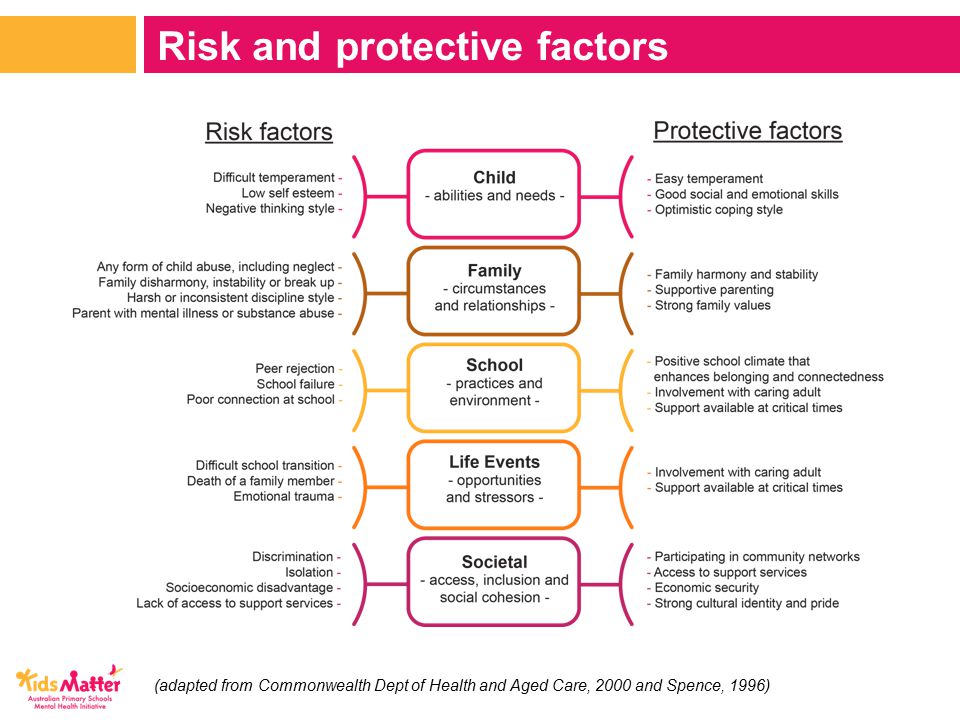

There are several pre-existing individual and societal risk factors associated with PTSD.

Gender, age at trauma, lower levels of education, lower socioeconomic status, pre-existing trauma, adverse childhood experiences, marital status, poor social support, and initial severity of the reaction to the trauma are some factors (Kroll, 2003; Stein, Walker, & Hazen, 1997; Sareen, 2014).

Genetic research has also suggested a relationship between the development of PTSD and specific genes (Zhao et al., 2017) and receptor proteins (Miller, Wolf, Logue, & Baldwin, 2013).

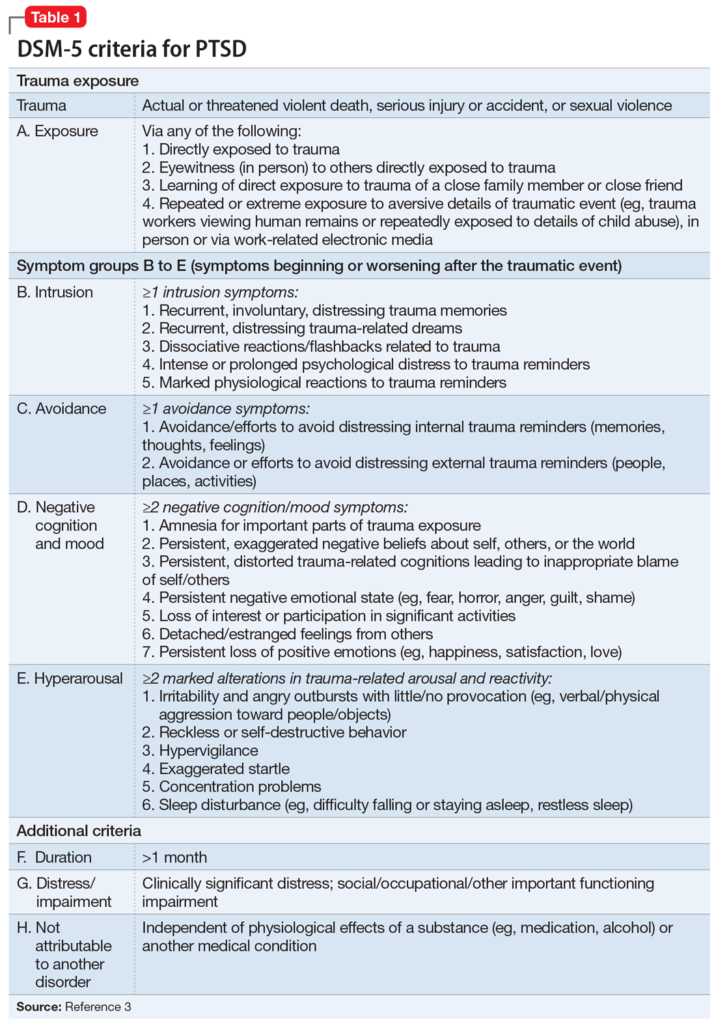

5. Criteria symptoms for PTSD

The criteria for PTSD are intrusive thoughts, nightmares, and flashbacks of past traumatic events; avoidance of reminders of trauma; hypervigilance; and sleep disturbance (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These can lead to considerable social, occupational, and interpersonal dysfunction (Bryant, Friedman, Spiegel, Ursano, & Strain, 2011).

For a person to be diagnosed with PTSD, the symptoms must last for more than a month and cause significant distress or problems in the individual’s daily functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

6 Possible PTSD Treatment Options and Paths

PTSD has several possible treatment pathways.

Treatment preferences are related to the method used for treatment and efficacy (Schwartzkopff, Gutermann, Steil, & Müller-Engelmann, 2021).

1. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is perhaps one of the most preferred therapeutic treatment choices for PTSD. An extensive evidence base shows its effectiveness (Monson & Shnaider, 2014). It can be planned for an individual or group format (Warman, Grant, Sullivan, Caroff, & Beck, 2005).

Trauma-focused CBT directly addresses memories, thoughts, and feelings related to the traumatic event (Monson & Shnaider, 2014).

The client is requested to focus and confront the traumatic experience in a session by thinking about the trauma in greater detail. This helps to identify unhelpful thinking patterns and distortions and replace these with realistic thoughts (Malkinson, 2010). It increases the ability to cope by reducing escape and avoidance behaviors through exposure in a controlled manner (Hawley, Rector, & Laposa, 2016).

2. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR)

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy was initially developed in 1987 to treat PTSD (Shapiro, 2007) and has shown to be clinically effective in children and adults (Chen et al. , 2018).

, 2018).

Unprocessed memories contain emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and physical sensations that occurred during the event (Shapiro, 1995). When memories are triggered, these stored disturbances cause the symptoms of PTSD or other disorders (Aranda, Ronquillo, & Calvillo, 2015).

EMDR is based on the idea that symptoms of PTSD result from past disturbing experiences that continue to cause distress because the memory was not adequately processed (Shapiro, 1995).

EMDR therapy focuses on the memory and how it is stored, reducing and eliminating the problematic symptoms (Shapiro, 2014).

The therapy incorporates the use of eye movements and other forms of rhythmic left–right (bilateral) stimulation, such as with tones or taps (Shapiro, 2007). When clients focus on the trauma memory and simultaneously experience bilateral stimulation, the vividness and emotion are reduced (Shapiro, 1995).

3. Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET)

Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) is another treatment for PTSD that may be more complex due to political, cultural, or social influences (Elbert & Schauer, 2002; Schauer, Neuner, & Elbert, 2011).

NET is currently included in the suggested interventions for treating PTSD in adults individually and in a group setting (Schauer et al., 2011).

A person’s narrative influences how they perceive their experiences. Framing life around the traumatic experiences leads to a feeling of persistent trauma and distress (Elbert & Schauer, 2002; Schauer et al., 2011).

The treatment focuses on imaginary trauma exposure and reorganizing memories (Schnyder et al., 2015). The therapist and client work to create the client’s timeline in sessions, and the client receives the written narrative as a testimony of their life at the end of treatment sessions (Schnyder et al., 2015).

4. Prolonged Exposure Therapy

Prolonged Exposure Therapy, developed by Professor Edna Foa from the University of Pennsylvania, teaches individuals to approach their trauma-related memories, feelings, and situations (Watkins, Sprang, & Rothbaum, 2018). Clients learn that trauma-related memories and cues are not dangerous and should not be avoided (Foa & Rothbaum, 1998).

By facing what has been avoided, a person can decrease symptoms of PTSD. Both imaginal and in vivo exposure are used at the pace dictated by the patient (Eftekhari, Stines, & Zoellner, 2006).

This treatment is recommended for PTSD (Rauch, Eftekhari, & Ruzek, 2012).

5. Medications

There is no single medication solely for the treatment of PTSD. As the condition presents with both anxiety and depression, the best medication depends on the primary symptoms experienced (Marken & Munro, 2000).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can be helpful in managing these symptoms (Marken & Munro, 2000).

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are often used to treat depression (Fasipe, 2019). Research has found venlafaxine, a SNRI, to be most effective with PTSD patients (Davidson et al., 2006).

6. Psychedelic-assisted therapy

A controversial therapy, highlighting a significant paradigm shift for the treatment of PTSD, involves the use of psychedelic drugs (Doblin, 2002; Pilecki, Luoma, Bathje, Rhea, & Narloch, 2021). These drugs alter perception and consciousness, producing auditory and visual hallucinations (Morgan, 2020).

These drugs alter perception and consciousness, producing auditory and visual hallucinations (Morgan, 2020).

Psychedelic drugs such as MDMA are a potential breakthrough in the treatment of severe PTSD (Mitchell et al., 2021). They help to regulate the severe symptoms of the disorder, especially dissociative states (Frewen & Lanius, 2006). This treatment allows the patient to build trust in the therapeutic relationship (Mitchell et al., 2021).

Unfortunately, you can’t bring a box of pills to your client’s next session. Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is regulated and therapists must gain extensive approved and accredited training and certification.

Read more about this in our article Is Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy Effective? 6 Research Findings.

How to Help Clients With PTSD and Trauma

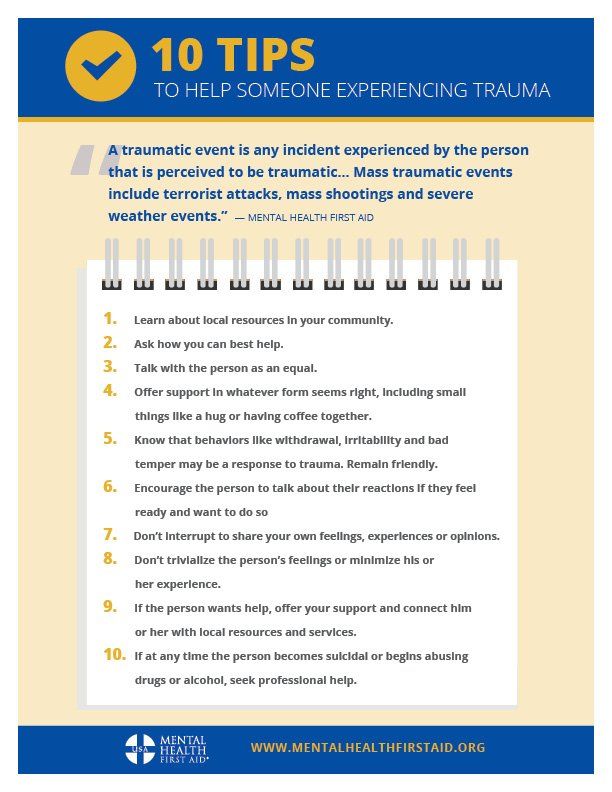

Clients with trauma and PTSD will require focused help with their therapeutic needs. The following are guidelines for helping PTSD clients.

1. Ensure your client they are not to blame

Clients who have gone through trauma and may be experiencing PTSD often feel they are to blame (Bub & Lommen, 2017). This usually leaves them with tremendous guilt, especially survivor guilt and blame (Murray, Pethania, & Medin, 2021).

This usually leaves them with tremendous guilt, especially survivor guilt and blame (Murray, Pethania, & Medin, 2021).

It is important to state to the client explicitly that they are not to blame, and the therapy will help them eventually see that.

2. Do not avoid talking about trauma for fear of re-traumatizing

PTSD is a disorder that creates and maintains avoidance (Lancaster, Teeters, Gros, & Back, 2016). You may fear causing distress and re-traumatizing the client by talking about their past trauma and upsetting them. Understandably, you want to make your clients feel happy and soothe them. Exposing them to the past trauma in a controlled and safe manner can help them undo the trauma.

3. Use creative therapy to work through trauma

Creative therapies can be used alongside or as a precursor to other therapies (Schouten, de Niet, Knipscheer, Kleber, & Hutschemaekers, 2014).

Working through trauma with art can help clients process painful, traumatic experiences without speaking about them, which might be too overwhelming. Some clients might find writing things down helpful.

Some clients might find writing things down helpful.

4. Measure progress of symptoms

It is essential to chart the progress of your client’s symptoms with a brief assessment tool.

The Impact of Event Scale-Revised (Weiss, 2007) can be used for PTSD symptoms. It provides different sub-scores for hyperarousal, avoidance, and intrusion.

Track the severity of symptoms at baseline, intermediate stage, and end of the sessions to monitor the scores and look for improvements with the chosen intervention.

Using CBT to Heal Trauma: A Guide

There are many variations in how a therapist may perform trauma-focused CBT.

This is what the stages of therapy may look like.

1. Assessment of symptoms

The first step is to assess the client through interviews to gather information on their trauma, triggers, and symptoms. This will provide the best treatment plan for them.

2. The rationale for treatment

Next, give the client an in-depth analytical overview of their PTSD symptoms and easy-to-follow analogies to allow them to understand their trauma.

3. Eliminate thought suppression

Tell your client not to suppress their thoughts but to allow them to arise automatically. This will eliminate avoidance of distressing thoughts and allow them to address their fears.

4. Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation will help clients understand more about PTSD, how the brain reacts to trauma and exposure, and why their traumatic memories have not been processed (Bremner, 2006).

5. Relaxation methods

Make use of relaxation methods to help clients reduce stress. You may include breathing exercises, guided imagery, and muscle relaxation.

6. Cognitive restructuring

Your client will now be asked to relive their trauma under safe conditions. Target specific areas and ask them to describe the event at a moment-by-moment detail, as if they were reliving the experience. This step will support them in processing memories.

7. Identifying triggers

At this stage, ask your client to identify harmful triggers that have resurfaced as intrusive memories of negative thoughts. You will support them to distinguish the triggers, learn how they are not associated with the event, and learn how to separate the concepts.

You will support them to distinguish the triggers, learn how they are not associated with the event, and learn how to separate the concepts.

8. Imagery techniques

Imagery techniques are helpful in changing the meaning of a memory (Arntz, 2012). Ask your client to view the image from a different perspective. This technique will support your clients to increase their insight to allow information to be processed more effectively.

2 Helpful Worksheets for Adults & Youth

Worksheets can help you gain more information about your client’s trauma and how it affects them.

1. Understanding PTSD triggers

This worksheet from Mylemarks allows your client to identify triggers that lead to anxiety. The client has to identify three triggers and notice the changes when that happens. It can be used with adolescents and adults, individuals and groups.

2. Simple CBT

This simple CBT worksheet explains the CBT model, clarifying the process of automatic thoughts, and how problems occur. The worksheet allows clients to reflect on their reactions to a given situation.

The worksheet allows clients to reflect on their reactions to a given situation.

This sheet is suitable for adolescents and adults. It is helpful for individual and group sessions too.

A Look at Trauma Psychoeducation: 2 Worksheets

These two worksheets can assist with psychoeducation for those traumatised.

1. Autonomic nervous system

Psychoeducation is often used to deal with trauma (Wessely et al., 2008).

Psychoeducation has been described as psychological first aid (Gray, Litz, & Papa, 2006).

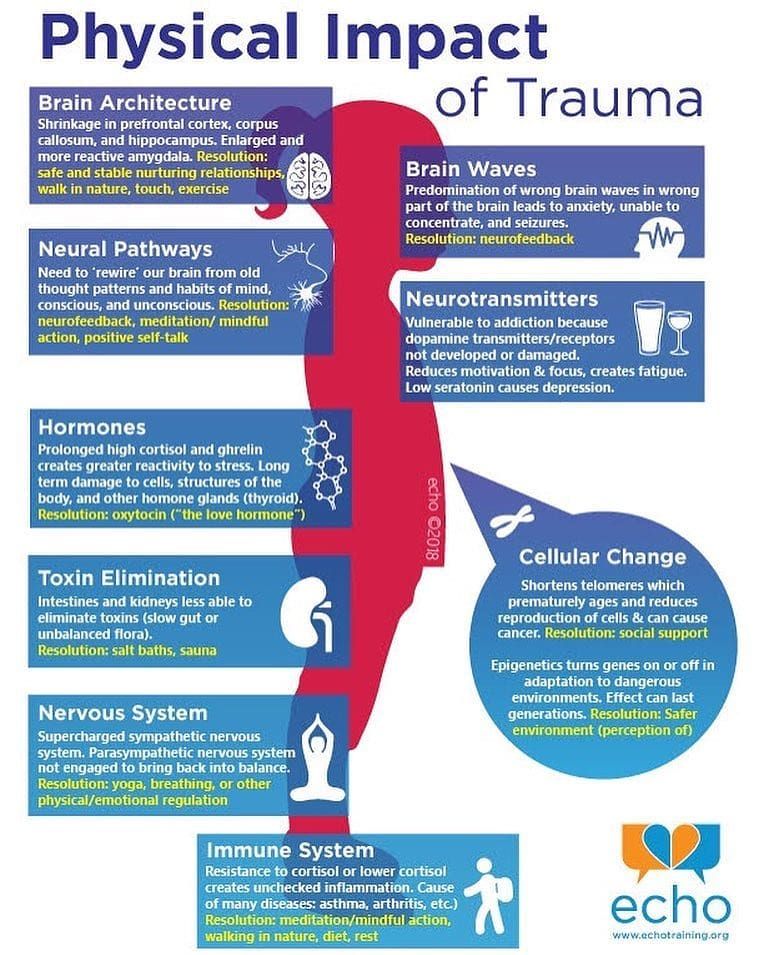

The autonomic nervous system regulates the body systems outside of voluntary control (McCorry, 2007). This worksheet helps clients understand the uncontrollable intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms they may experience.

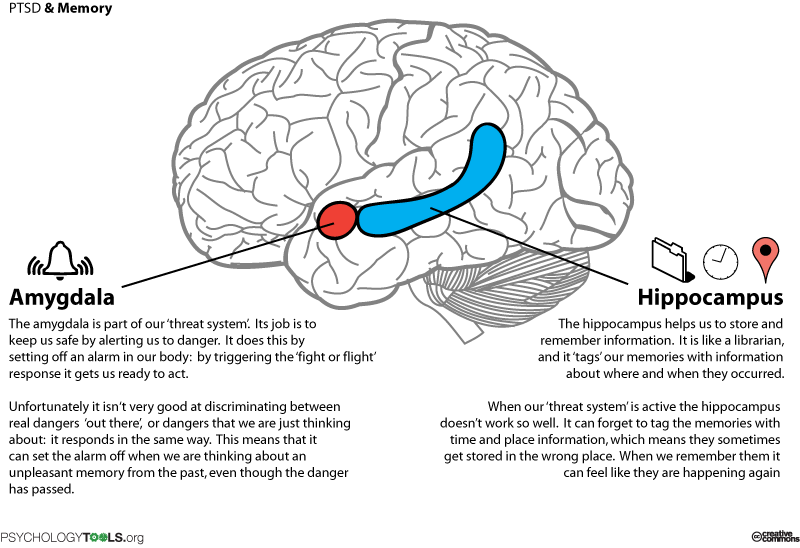

2. The traumatized brain

Alterations of brain processing in normal and traumatic material are responsible for the intrusive nature of memories in conditions such as PTSD (Brewin, Dalgleish, & Joseph, 1996). This handout simply explains the changes in memory thought to occur in PTSD.

This handout simply explains the changes in memory thought to occur in PTSD.

A Note on Group Therapy for Clients With PTSD

If your client is seeking treatment for PTSD, you may wish to help them decide whether to opt for individual or group therapy. There have been mixed opinions on group therapy versus individual therapy (Sloan, Unger, & Beck, 2016).

The following points may help your clients make the right decision.

1. Validation of the problem

Clients can see others in the group experiencing sleep, appetite, cognitive, anger, and emotional problems. This helps clients to validate the same experiences.

2. Helping others

The ability to help others can promote your client’s self-esteem, confidence, and self-belief in coping with and managing PTSD symptoms.

3. Social support

Group therapy can help people living with PTSD overcome the negative impact of trauma. Clients will feel they are not alone and can form a supportive network.

4. Limitations of personal attention from the therapist

A disadvantage of group therapy is that the attention from the facilitator is divided among the participants. Some clients may feel they need more attention that can only be received through individual focus rather than a group format.

5. Confidentiality

Individuals with PTSD may experience feelings of mistrust and paranoia and have skewed judgments about the intentions of others (Freeman et al., 2013). They may be reluctant to open up and share their experiences with others in a group. This will need to be considered when deciding on which modality of intervention to take.

Resources From PositivePsychology.com

There are several helpful resources that can help you support clients who have PTSD or other trauma.

17 Validated resilience & coping tools for practitioners

This science-based and fully referenced set of 17 resilience tools for practitioners is available for purchase on our website and covers many resilience topics.

There are tools on strength spotting, optimism, coping, emotional avoidance, and growth mindset, to name a few.

They are valuable in assisting clients who may experience trauma, PTSD, and any other emotional difficulties and setbacks in life. When used regularly with clients who have had negative life experiences, these tools can help them see setbacks as opportunities for growth through a changed perspective.

Growing Stronger From Trauma

This is a free worksheet that will help clients identify their strengths following trauma. It is vital that clients can see the positives to move forward with their lives.

Breath Awareness

Relaxation exercises, including breathing work, can help minimize feelings of stress. This free simple breathing exercise can help clients relax and reduce hyperarousal from their trauma symptoms.

A Take-Home Message

It is inevitable that trauma will come to us at least once, if not more than once, throughout life (Copeland et al. , 2007). It is even more unfortunate that some of us will develop PTSD when the trauma does not resolve.

, 2007). It is even more unfortunate that some of us will develop PTSD when the trauma does not resolve.

Gone are the days when PTSD was considered ‘shell shock’ and ‘combat trauma’ (Myers, 1915; Marlowe, 2001).

Thankfully, it is now recognized as a set of symptoms belonging to a formal anxiety disorder that can be debilitating (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and affect anyone, although some people are more susceptible. All is not lost, for some excellent treatment options and pathways are now available.

This article has been very informative about trauma, PTSD, and treatment pathways. We hope you enjoyed reading it as much as we enjoyed writing it for you.

The worksheets, psychoeducation, and information on whether to use individual or group sessions will hopefully inform your work with clients who have been traumatized. You can now support them in making wise changes and moving forward again in life.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Aranda, B. D. E., Ronquillo, N. M., & Calvillo, M. E. N. (2015). Neuropsychological and physiological outcomes pre- and post-EMDR therapy for a woman with PTSD: A case study. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 9(4), 174–187.

- Arntz, A. (2012). Imagery rescripting as a therapeutic technique: Review of clinical trials, basic studies, and research agenda. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 3(2), 189–208.

- Beals, J., Manson, S. M., Croy, C., Klein, S. A., Whitesell, N. R., Mitchell, C. M., & AI-SUPERPFP Team. (2013). Lifetime prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in two American Indian reservation populations. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(4), 512–520.

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28.

- Bremner J. D. (2006). Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 8(4), 445–461.

- Brewin, C. R., Dalgleish, T., & Joseph, S. (1996). A dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Review, 103(4), 670–686.

- Bryant, R. A., Friedman, M. J., Spiegel, D., Ursano, R., & Strain, J. (2011). A review of acute stress disorder in DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(9), 802–817.

- Bub, K., & Lommen, M. J. J. (2017). The role of guilt in posttraumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1407202.

- Chen, R., Gillespie, A., Zhao, Y., Xi, Y., Ren, Y., & McLean, L. (2018). The efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in children and adults who have experienced complex childhood trauma: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(9), 534.

- Copeland, W. E., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2007). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(5), 577–584.

- Creamer, M., Burgess, P., & McFarlane, A. C. (2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder: Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Psychological Medicine, 31(7), 1237–1247.

- Davidson, J., Baldwin, D., Stein, D. J., Kuper, E., Benattia, I., Ahmed, S., … Musgnung, J. (2006). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder with venlafaxine extended release: A 6-month randomized controlled Trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(10), 1158–1165.

- Doblin, R. (2002). A clinical plan for MDMA (ecstasy) in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Partnering with the FDA. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 34(2), 185–194.

- Elbert, T., & Schauer, M. (2002). Burnt into memory.

Nature, 419(6910), 883.

Nature, 419(6910), 883. - Eftekhari, A., Stines, L. R., & Zoellner, L. A. (2006). Do you need to talk about it? prolonged exposure for the treatment of chronic PTSD. The Behavior Analyst Today, 7(1), 70–83.

- Fasipe, O. J. (2019). The emergence of new antidepressants for clinical use: Agomelatine paradox versus other novel agents. IBRO Reports, 9(6), 95–110.

- Frewen, P. A., & Lanius, R. A. (2006). Toward a psychobiology of posttraumatic self-dysregulation: Reexperiencing, hyperarousal, dissociation, and emotional numbing. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1071, 110–124.

- Foa, E. B., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1998). Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. Guilford Press.

- Freeman, D., Thompson, C., Vorontsova, N., Dunn, G., Carter, L. A., Garety, P., … Ehlers, A. (2013). Paranoia and post-traumatic stress disorder in the months after a physical assault: A longitudinal study examining shared and differential predictors.

Psychological Medicine, 43(12), 2673–2684.

Psychological Medicine, 43(12), 2673–2684. - Gray, M., Litz, B., & Papa, A. (2006). Crisis debriefing: What helps, and what might not. Good intentions are admirable, but providing effective treatment contributes more. Current Psychiatry, 10, 17–29.

- Hawley, L. L., Rector, N. A., & Laposa, J. M. (2016). Examining the dynamic relationships between exposure tasks and cognitive restructuring in CBT for SAD: Outcomes and moderating influences. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 39, 10–20.

- Kessler, R. C., Rose, S., Koenen, K. C., Karam, E. G., Stang, P. E., Stein, D. J., … Viana, M. (2014). How well can post-traumatic stress disorder be predicted from pre-trauma risk factors? An exploratory study in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry, 13(3), 265–274.

- Kroll, J. (2003). Posttraumatic symptoms and the complexity of responses to trauma. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 290(5), 667–670.

- Lancaster, C. L., Teeters, J. B., Gros, D. F., & Back, S. E. (2016). Posttraumatic stress disorder: Overview of evidence-based assessment and treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 5(11), 105.

- Marken, P. A., & Munro, J. S. (2000). Selecting a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor: Clinically important distinguishing features. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 2(6), 205–210.

- Malkinson, R. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral grief therapy: The ABC model of rational-emotion behavior therapy. Psihologijske Teme, 19(2), 289–305.

- Marlowe, D. H. (2001). Psychological and psychosocial consequences of combat and deployment with special emphasis on the Gulf War. RAND Corporation.

- McCorry, L. K. (2007). Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 71(4), 78.

- Morgan, L. (2020). MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for people diagnosed with treatment-resistant PTSD: What it is and what it isn’t.

Annals of General Psychiatry, 19, 33.

Annals of General Psychiatry, 19, 33. - Monson, C. M., & Shnaider, P. (2014). Treating PTSD with cognitive-behavioral therapies: Interventions that work. American Psychological Association.

- Miller, M. W., Wolf, E. J., Logue, M. W., & Baldwin, C. T. (2013). The retinoid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORA) gene and fear-related psychopathology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151, 702–708.

- Mitchell, J. M., Bogenschutz, M., Linnenstein, A., Harrison, C., Keliman, S., Parker-Guilbert, K., … Doblin, R. (2021). MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nature Medicine, 27, 1025–1033.

- Murray, H., Pethania, Y., & Medin, E. (2021). Survivor guilt: A cognitive approach. Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 14, e28.

Myers, C. S. (1915). A contribution to the study of shell shock.: Being an account of three cases of loss of memory, vision, smell, and taste, admitted into the Duchess of Westminster’s War Hospital, Le Touquet. The Lancet, 185(4772), 316–330.

The Lancet, 185(4772), 316–330. - Neria, Y., Nandi, A., & Galea, S. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 38(4), 467–80.

- Pilecki, B., Luoma, J. B., Bathje, G. J., Rhea, J., & Narloch, V. F. (2021). Ethical and legal issues in psychedelic harm reduction and integration therapy. Harm Reduction Journal, 18, 40.

- Rauch, S. A., Eftekhari, A., & Ruzek, J. I. (2012). Review of exposure therapy: A gold standard for PTSD treatment. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 49(5), 679–687.

- Sareen, J. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: Impact, comorbidity, risk factors, and treatment. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(9), 460–467.

- Schauer, M., Neuner, F., & Elbert, T. (2011). Narrative exposure therapy. A short-term intervention for traumatic stress disorders after war, terror or torture.

Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

Hogrefe & Huber Publishers. - Schnyder, U., Ehlers, A., Elbert, T., Foa, E. B., Gersons, B. P. R., Resick P. A., … Cloitre, M. (2015). Psychotherapies for PTSD: What do they have in common? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, 28186.

- Schouten, K. A., de Niet, G. J., Knipscheer, J. W., Kleber, R. J., & Hutschemaekers, G. J. M. (2014). The effectiveness of art therapy in the treatment of traumatized adults. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(2), 220–228.

- Schwartzkopff, L., Gutermann, J., Steil, R., & Müller-Engelmann, M. (2021). Which trauma treatment suits me? Identification of patients’ treatment preferences for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 12.

- Shapiro, F. (1995). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures. Guilford Press.

- Shapiro, F. (2007). EMDR, adaptive information processing, and case conceptualization.

Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 1(2), 68–87.

Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 1(2), 68–87. - Shapiro, F. (2014). The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: Addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences. The Permanente Journal, 18(1), 71–77.

- Sloan, D. M., Unger, W., & Beck, J. G. (2016). Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for veterans diagnosed with PTSD: Design of a hybrid efficacy-effectiveness clinical trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 47, 123–130.

- Stein, M. B., Walker, J. R., & Hazen, A. L. (1997). Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: Findings from a community survey. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1114–1119.

- van der Kolk, B. A., McFarlane, A. C., & Weisaeth, L. (1996). Traumatic stress: The effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body, and society. Guilford Press.

- van der Kolk, B.

(2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2(1), 7–22.

(2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2(1), 7–22. - Warman, D. M., Grant, P., Sullivan, K., Caroff, S., & Beck, A. T. (2005). Individual and group cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychotic disorders: A pilot investigation. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 11(1), 27–34.

- Watkins, L., Sprang, K., & Rothbaum, B. (2018). Treating PTSD: A review of evidence-based psychotherapy interventions. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 2(12), 258.

- Weiss, D. S. (2007). The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. In J.P. Wilson & C.S. Tang (Eds.), Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 219–238). Springer.

- Wessely, S., Bryant, R. A., Greenberg, N., Earnshaw, M., Sharpley, J., & Hughes, J. H. (2008). Does psychoeducation help prevent post traumatic psychological distress? Psychiatry, 71(4), 287–302.

- Zhao, M., Yang, J., Wang, W., Ma, J., Zhang, J., Zhao, X., … Yang, Y. (2017). Meta-analysis of the interaction between serotonin transporter promoter variant, stress, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 16532.

Working with trauma in different psychotherapy approaches: The body aspect | Training course

Working with trauma in various approaches of psychotherapy: The corporeal aspect

Program leaders Anna Likuy, Olga Komissarova

Rosen Method School, educators, social workers, and all those working in the helping professions. nine0010

Why is the topic of working with trauma so important today? Indeed, in our world there have always been natural disasters, wars, loss of loved ones, serious illnesses and various situations that injure people. But what has changed now?

At a time when there was no television and the Internet, a person, getting injured, was alone with his injury and could even somehow experience it and, possibly, cope with it. Today we all live in a huge information flow from all possible channels of information. And a person is not only injured himself during his life, but is also forced to become an unwitting witness to crises, wars, troubles and horrors of other people already on a global scale, that is, co-traumatization is added to personal injuries. Since this happens every day, sometimes for many hours a day, we can talk not about an increase in the number of injuries as such, there are no more, but about an increase in the traumatism of the very "field" in which we live. nine0003

Today we all live in a huge information flow from all possible channels of information. And a person is not only injured himself during his life, but is also forced to become an unwitting witness to crises, wars, troubles and horrors of other people already on a global scale, that is, co-traumatization is added to personal injuries. Since this happens every day, sometimes for many hours a day, we can talk not about an increase in the number of injuries as such, there are no more, but about an increase in the traumatism of the very "field" in which we live. nine0003

In this regard, many helping professions have appeared, such as employees of the Ministry of Emergency Situations, psychologists, social workers, etc. And we all understand how high the demand for specialists is becoming, who can work both with long-term trauma, but can also orient themselves and provide assistance in cases acute injuries.

Our Body Therapy program offers participants the theoretical basic knowledge of working with trauma, such as the concept of trauma, types, classification of traumas, etc. in various psychological approaches. The course is based on work with psychological trauma. In practical terms, students will get acquainted with various approaches to working with trauma in body-oriented psychotherapy: I. Reich's character analysis, A. Lowen's bioenergetic analysis, A. Boadella's biosynthesis, L. Marcher's bodynamics, M. Rosen's Rosen method, and others. You will also get acquainted with bodily practices, the so-called “Body-work”, which are not psychotherapy in themselves, but we will show you that their techniques and techniques can also be used in working with trauma if you understand the basic rules of psychotherapy. These are the Feldenkrais Method, Rosen Movement, etc.

in various psychological approaches. The course is based on work with psychological trauma. In practical terms, students will get acquainted with various approaches to working with trauma in body-oriented psychotherapy: I. Reich's character analysis, A. Lowen's bioenergetic analysis, A. Boadella's biosynthesis, L. Marcher's bodynamics, M. Rosen's Rosen method, and others. You will also get acquainted with bodily practices, the so-called “Body-work”, which are not psychotherapy in themselves, but we will show you that their techniques and techniques can also be used in working with trauma if you understand the basic rules of psychotherapy. These are the Feldenkrais Method, Rosen Movement, etc.

For greater efficiency in working with trauma, we would like to show you that it is becoming more and more relevant to address the corporeal aspect of neighboring, non-corporeal areas of psychotherapy, for example: N. Linde's Emotional Imagery Therapy, art therapy, 3rd wave cognitive therapy F. Shapiro DPDH (desensitization and processing by eye movement), that is, in those directions where the role of corporeality was previously ignored. Increasingly, the evidence comes from the latest scientific research, which also shows the importance of paying attention to the bodily aspects of dealing with trauma. nine0003

Shapiro DPDH (desensitization and processing by eye movement), that is, in those directions where the role of corporeality was previously ignored. Increasingly, the evidence comes from the latest scientific research, which also shows the importance of paying attention to the bodily aspects of dealing with trauma. nine0003

Thus, the uniqueness of our course on body psychotherapy in working with trauma lies in the reliance on the body aspect of working with trauma in the body and non-body areas of psychotherapy. Students will get acquainted with the basic principles on how to work with acute and old traumas in various areas of psychotherapy as safely and carefully as possible, since only the competent use of the proposed tools will help not to cause a new injury and be effective in working with a client. nine0003

In the course program:

- The concept of "trauma" in psychotherapy

- Injury classification

- Somatic experience according to P.

Levin

Levin - Body-oriented psychotherapy and its representatives

- A. Lowen's bioenergetic analysis - about trauma and the possibility of interacting with it

- The concept of "Character Structure" as a diagnostic material for identifying trauma and possible work with it

- Rosen method. His ideas about working with trauma. Borders, space, body. Creating a "security container"

- M. Feldekrais - bodywork techniques and their use in dealing with trauma

- Rosen movement as a way to restore the psychophysical integrity lost during trauma through physical movement

- Art approach - basic concepts. The physical aspect in working with trauma

- N. D. Linde's Ten-Step EOT Model for Trauma Work, Body Aspect of Work

- Processing of traumatic material with the help of eye movement (EMT). Method F. Shapiro. Cognitive psychotherapy, body aspect

- Working with strong feelings or their absence in trauma in different approaches

Course modules

Module 1.

Block 1

Trauma. Basic approaches and classification. The concept of "injury". Basic approaches and classification. P. Levin "Healing Trauma" - an approach to trauma as a somatic experience. Fundamentals of psychological work with trauma.

Block 2

Body-oriented therapy. nine0026 A progressive step in psychotherapy is the emergence of a body-oriented approach. Main schools and representatives of the direction. Character analysis of W. Reich. Bioenergetic analysis by A. Lowen. Biosynthesis by D. Boadell. Bodynamics L. Marcher et al. Basic concepts of the approach - Energy. Grounding. Breath. The importance of the bodily aspect in working with trauma.

Block 3

Bioenergy analysis by A. Lowen. One of the leading areas of body-oriented psychotherapy. Body reading. Character structures and their characteristics in terms of the occurrence of developmental traumas and work with them. Schizoid and oral characters. nine0003

Schizoid and oral characters. nine0003

Block 4

Bioenergy analysis by A. Lowen. Working with developmental trauma. Character structures as a reflection of developmental traumas in the human body. Body reading. Masochistic, narcissistic, rigid characters.

Module 2

Block 5

Working with trauma in the rosen method. Definition and symptoms of injury. Contraindications to rosen therapy. Trauma recognition, inner reality. Relationship between mental and physical symptoms and conditions. stages of healing. nine0003

Block 6

Working with trauma in the rosen method. Physical touch and safety container as necessary components of healing after trauma. The importance of working with the diaphragm to achieve integration. Features of verbal contact in Rosen-work with trauma. Restoration of mental and physiological self-regulation. The client's choice of liberation from survival patterns.

The client's choice of liberation from survival patterns.

Block 7

The M. Feldenkrais Method is a body practice that helps in working with trauma. nine0026 Basic concepts of the method: Functional integration. Body awareness. Acquaintance with the techniques of working with the body: restoring the image of oneself at the physiological level through the restoration of connections between the motor areas of the cerebral cortex and muscles. Using these techniques to work with trauma.

Block 8

Rosen-movement as a way to independently maintain a resource in complex work with trauma. Features of the rosen movement (musical accompaniment, rhythm, interaction with the group) and their impact on rehabilitation. Awareness and acceptance of the limits of one's physical body as a stage of healing from trauma. The importance of diaphragm release and the possibility of integration. Restoring the psychophysical integrity lost in trauma through physical movement. nine0003

nine0003

Module 3

Block 9

Art therapy - approaches to working with trauma. Art therapy as the oldest way of working with trauma. Close connection of sensory and emotional processes occurring in the body during visual activity. Focusing the client on bodily sensations and living them to work with trauma.

Block 10

N. Linde's Emotional Imagery Therapy - work with trauma. The author's technique of our contemporary, Russian scientist, Doctor of Psychology, Professor N.D. Linde. His classification of emotional traumas and work with them in the EOT approach. Ten-step model of work in EOT in work with injuries. The importance of the bodily aspect is work with bodily clamps according to W. Reich. nine0003

Block 11

CBT - Cognitive Behavioral Trauma Therapy - processing traumatic material with eye movement. Basic concepts of the method and psychophysiological mechanism as an adaptive information processing system of our body. Acquaintance with the classic DPG protocol. Emphasis on the bodily experience of traumatic events.

Acquaintance with the classic DPG protocol. Emphasis on the bodily experience of traumatic events.

Block 12

Essay. Group work. Final examination.

Summing up: Essay presentation. Group exercise. nine0067 Discussing your course results. Feedback.

Program structure

- the program lasts 3 months

- consists of three modules

- each module is a weekend meeting from 10:00 to 18:00, which includes a theoretical part and practical exercises (group, in pairs) to master the proposed techniques of working with a client; demonstration work is possible with any of the participants at their request, followed by a discussion in a general circle, a demonstration is possible. nine0030

Dress code: Loose, not restricting body movements.

The number of participants in the group is limited - no more than 16 people.

For a more complete and in-depth course, it is recommended to have 5 or more sessions of personal therapy in the framework of the proposed psychotherapeutic approaches (with the leaders of this course or other therapists recommended by them). This opportunity can help trainees gain their own personal experience of working effectively with traumatic experiences in solving personal problems and in more successful professional work with clients. nine0003

This opportunity can help trainees gain their own personal experience of working effectively with traumatic experiences in solving personal problems and in more successful professional work with clients. nine0003

Training leaders

Anna Likuy — psychologist, body-oriented, art therapist, certified specialist in the field of EMDR (desensitization, processing by eye movements), emotional-imaginative therapy; body practice trainer - Pilates, Feldenkrais. Postgraduate student at the Moscow Institute of Psychoanalysis, applicant for a Ph.D. in psychology.

Olga Komissarova — clinical psychologist, rosen therapist, director of the Russian school of the rosen method. Certificate of the Rosen Institute (Berkeley, USA). nine0003

Working with trauma: evo_lutio — LiveJournal

We will talk about psychological trauma.The topic is fashionable, because in psychology now is the time of beggars.

Everyone tries to speculate about trauma in order to extort something for themselves.

Injury - and now you are almost an invalid and everyone owes you.

Fortunately, the field is designed in such a way that any tongs make a person outcast.

That is, if you try to pull something from others, no matter what the arguments, they retreat from you and begin to shun you. nine0003

Hang more sour cabbage soup on yourself - and you are guaranteed a decline in all resources.

Your always sour and unhappy expression makes even your smell sour.

Therefore, even in the event of a real injury, it is in your interest to deal with it as quickly as possible and forget it.

Most beggars do not want to forget anything, they restore, nourish and grow their trauma and even "injury" again and again in order to be able to wring out compensation. nine0003

And very quickly find themselves in a hole in all resources, because beggars are disliked by everyone, and especially by other beggars. They join when they want to collectively squeeze something out, but they don’t like it.

A real injury is an extremely rare thing, no matter what the beggars howl.

Trauma is a reaction of a normal psyche to an extraordinary event that breaks the usual defense system. The event must be extraordinary, not ordinary, that is, one that others do not encounter, it is not in the normal collective experience. Being the victim of a crashed plane, gang rape, armed robbery, prolonged torture or fire are events that are extraordinary. For a modern person to be in the center of hostilities is an extraordinary event. Our ancestors in many historical periods were adapted to this. That is, the conclusion - trauma or not - depends on collective patterns, and not on the individual reaction of a particular person. nine0003

This is the main thing that people who talk about trauma do not understand. Trauma is not just a nuisance, it is a breakdown that interferes with later life. And in their view, any stress can break a person. Mom took away the candy as a child and this is a trauma. The teacher in front of the whole class called stupid, trauma. The girl left, the injury. Fired from work, injured. Here is how it is now considered. And it is very harmful - to consider an ordinary event for others as your personal trauma. Weak, pampered by parasitism on others, the infantile psyche can react with strong stress to any obstacle, and this means only one thing: such a person is not adapted to a normal life, he is a burden for society and for himself. If you run around him with a first-aid kit and a fan, you can even deprive him of the chance to become a normal person. He is still ugly if he mourns the candy that was taken away in childhood, and if he is sympathized and treated with sweets to compensate, he will remain ugly. nine0003

The teacher in front of the whole class called stupid, trauma. The girl left, the injury. Fired from work, injured. Here is how it is now considered. And it is very harmful - to consider an ordinary event for others as your personal trauma. Weak, pampered by parasitism on others, the infantile psyche can react with strong stress to any obstacle, and this means only one thing: such a person is not adapted to a normal life, he is a burden for society and for himself. If you run around him with a first-aid kit and a fan, you can even deprive him of the chance to become a normal person. He is still ugly if he mourns the candy that was taken away in childhood, and if he is sympathized and treated with sweets to compensate, he will remain ugly. nine0003

It has nothing to do with trauma, like everything that is constantly experienced by many people, which is present in people's lives as an ordinary, ordinary event. Everything that other people experience in front of your eyes, you are also ready to experience and can become stronger from this experience. And if there is a desire to turn to psychological support because of the usual trouble, then you want to give up your own legs and are looking for crutches.

And if there is a desire to turn to psychological support because of the usual trouble, then you want to give up your own legs and are looking for crutches.

The desire to declare oneself as the most tender and sensitive creature, about the princess-on-a-pea, who through a hundred feather beds feels a small pea like a cobblestone, and subjectively her whole body is bruised - this is a diagnosis of a serious deviation in personal development. Psychological infantilism. nine0003

And people who use the word "trauma" just like that have very serious problems, not connected with trauma, but with the desire to parasitize on others.

Saying "my psyche is so sensitive that the birth of a child has become a trauma for me" is like saying "it's trauma for me to work, I want others to work for me" or even "it's trauma for me to walk, I want carried on hand." These are things of the same order, because in the first case, a person requires sympathy for what other people consider normal and even happiness. And his psyche is allegedly so weak that he perceives a joyful event as a catastrophe. He is a stupid beggar trying to pull on other people's resources. If he does not have organic problems with the brain, the whole point is in the spoiledness of such a person, in his desire to make other people his nannies and servants, to transfer elementary care of himself to them. nine0003

And his psyche is allegedly so weak that he perceives a joyful event as a catastrophe. He is a stupid beggar trying to pull on other people's resources. If he does not have organic problems with the brain, the whole point is in the spoiledness of such a person, in his desire to make other people his nannies and servants, to transfer elementary care of himself to them. nine0003

If you don't stop encouraging parasites in the present, the future will be lost.

That is, "traaavma" is most often forceps to force others to carry themselves around their necks like a beaten unbeaten one.

Fortunately, traumatists remain in the pit, not because of injury, but because of greed, stupidity and laziness. Accustomed to being the weakest and most miserable for the sake of other people's help, they do not develop any resources and do not receive any sympathy. Disgust and pity instead of sympathy are received. Unlike people who really experienced a disaster, an extraordinary traumatic event, but tried to get back on their feet after it. These are the people who evoke sympathy and desire to imitate. nine0003

These are the people who evoke sympathy and desire to imitate. nine0003

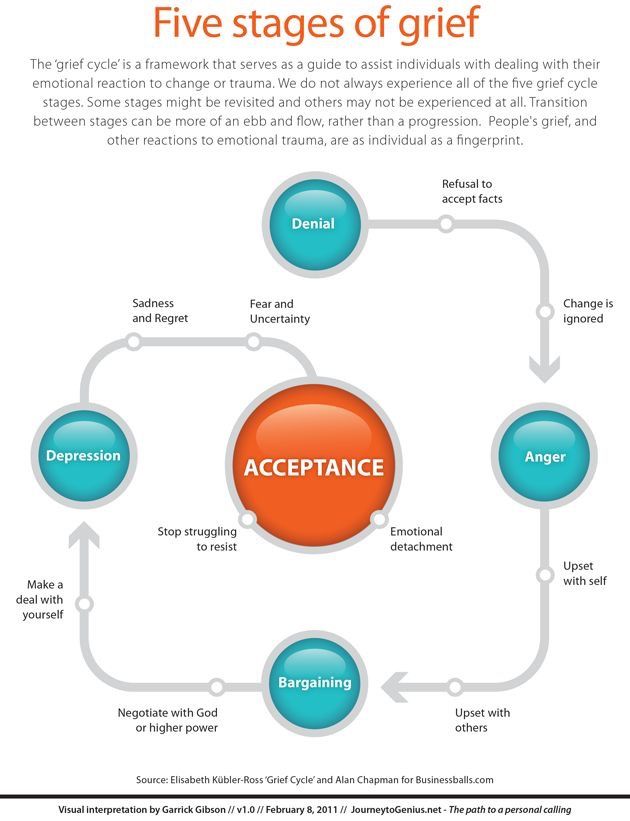

What if a very difficult event, and at the same time quite common, that is, something that happens to other people not so rarely: the death of a loved one, the betrayal of a spouse, the loss of a job, the loss of property, and the like misfortune caused you a real post-traumatic syndrome? What if you have persistent anxiety, sleep disturbances, flashbacks of panic attacks, features of depression or neurosis?

You need a doctor to prescribe medications based on your condition, but besides that, it is very important for you to choose the right settings. nine0003

The most important thing is to clearly define your goal. If your goal is to get out of PTSD as quickly as possible and fully recover, this is the right setting. With such an attitude, your psyche organizes all the necessary defenses, and a healthy psyche has a lot of them. You must engage in resources and strive to get out of an anxious, helpless state.

If your goal is to correct a situation in the past that has already happened, you will hang for a long time in thoughts about the past and will continually restore traumatic pictures. If your goal is to receive compensation (from God or society) - you can become disabled. Wrestling with an outstretched hand to a disabled person, so your brain will look for a way to create the most pathetic and painful look for you. nine0003

This is really the most important thing: what is your goal. Most people say they wish they could bounce back, but they don't. It seems to them that it will be "too easy" if the misfortune simply fades into the background. It seems to them that they will “betray themselves” in this way if they allow themselves to forget and calm down. They don't want to forget or settle down, so they hang in "trauma". They do not consider it important to continue a full and active life, to benefit loved ones and society, they want to suffer in order to receive some kind of compensation. nine0003

nine0003

Any work with "injury" and trauma must necessarily take this into account. Whether a person wants to go out or not, and if he really doesn’t want to, work with a person must necessarily include arguments about what he is depriving himself of by hanging over the pit.

In severe trauma (real, not "injury"), there is such a symptom as partial amnesia. The person does not remember what happened to him, but feels fear and helplessness. In this case, psychotherapy may include reconstructing the picture of the event. This is not necessary, you can go the other way, you can restore a person’s supports, bypassing memories, and then he will remember everything (already without panic) when he gets on his feet, but some psychotherapists prefer to pull suppressed memories to the level of consciousness, believing that with Irrational fear is harder to deal with. An experienced therapist can afford it. nine0003

But all this concerns only real amnesia, and a huge number of "trauma patients", seizing on this principle, do nothing but savor the pictures of the past, which, on the contrary, need to be pushed into the background and forgotten, so as not to keep them in the head in the foreground . In the foreground of consciousness is always placed an actual task, which you can actively deal with. The first plan is for direct work in the present. And when there is a picture of the past, your whole system freezes like a broken record on one squeaky note. Your whole psyche is engaged in recreating some episode, saturating it with colors, sounds and emotions. You are driving yourself crazy instead of bringing yourself back to normal. nine0003

In the foreground of consciousness is always placed an actual task, which you can actively deal with. The first plan is for direct work in the present. And when there is a picture of the past, your whole system freezes like a broken record on one squeaky note. Your whole psyche is engaged in recreating some episode, saturating it with colors, sounds and emotions. You are driving yourself crazy instead of bringing yourself back to normal. nine0003

A responsible adult cannot afford this. He can't sit down and chew snot while his entire area of responsibility is suffering right in front of him. If you have a small child, you cannot mourn unhappy love for too long and heart-rendingly, you are forced to take care of the child. If you have a serious job and obligations to other people, you also cannot afford to relax and indulge in grief.

Therefore, the more responsible and active you are, the stronger your support. nine0003

And the more irresponsible, selfish and idle you are, the more important traaaavma becomes in your life.