Why does birth control cause depression

Hormonal contraception and mood disorders

Aust Prescr. 2022 Jun; 45(3): 75–79.

Published online 2022 Jun 1. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2022.025

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Hormonal contraception is known to precipitate or perpetuate depression in some patients. The link between oral contraceptive pills and depression relates to the amount and type of progestogen contained in these pills.

Many of the older oral contraceptive pills, which contain ethinylestradiol, are linked to severe mood problems. Newer oral contraceptive pills containing physiological forms of oestrogen may be better tolerated with a purported weaker link to mood problems.

Clinicians should consider the temporal relationship between the use of hormonal contraception and development of new or worsened depression or mood changes.

Keywords: mood, oestrogen, oral contraceptive pill, progesterone, progestogen

There are several different forms of contraception available for women. Some of these contain progestogen alone and others contain both oestrogen and progestogen.

There are several forms of long-acting progestogen-only contraception available, including levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, subdermal implants that release etonogestrel, and medroxyprogesterone acetate intramuscular injections. There are also three different types of progestogen-only pills ().

Table 1

Progestogen-only hormonal contraceptives

| Progestogen | Progestogen content | Brand name |

|---|---|---|

| Levonorgestrel, oral | 30 micrograms | Microlut |

| Levonorgestrel, intrauterine device | 19. 5 mg 5 mg | Kyleena |

| 52 mg | Mirena | |

| Norethisterone, oral | 350 micrograms | Noriday 28 |

| Drospirenone | 4 mg | Slinda |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate, intramuscular injection | 150 mg | Depo-Provera |

Open in a separate window

Combined contraception is available as a vaginal ring, but combined oral contraceptive pills are the most common form of contraception for women of reproductive age. These contain synthetic analogues of oestrogen and progesterone, which prevent pregnancy by acting locally on reproductive organs and centrally impeding the hypothalamic–pituitary– ovarian axis. Typically, the oestrogen component of oral contraceptive pills contains 20–50 micrograms ethinylestradiol, although newer oral contraceptive pills contain physiological forms of oestrogen such as estradiol and estradiol valerate. The progesterone component is usually a 19-nortestosterone derivative, such as desogestrel, etynodiol diacetate, gestodene, levonorgestrel, lynestronol, norethisterone, norethisterone acetate, norgestimate or norgestrel.

These contain synthetic analogues of oestrogen and progesterone, which prevent pregnancy by acting locally on reproductive organs and centrally impeding the hypothalamic–pituitary– ovarian axis. Typically, the oestrogen component of oral contraceptive pills contains 20–50 micrograms ethinylestradiol, although newer oral contraceptive pills contain physiological forms of oestrogen such as estradiol and estradiol valerate. The progesterone component is usually a 19-nortestosterone derivative, such as desogestrel, etynodiol diacetate, gestodene, levonorgestrel, lynestronol, norethisterone, norethisterone acetate, norgestimate or norgestrel.

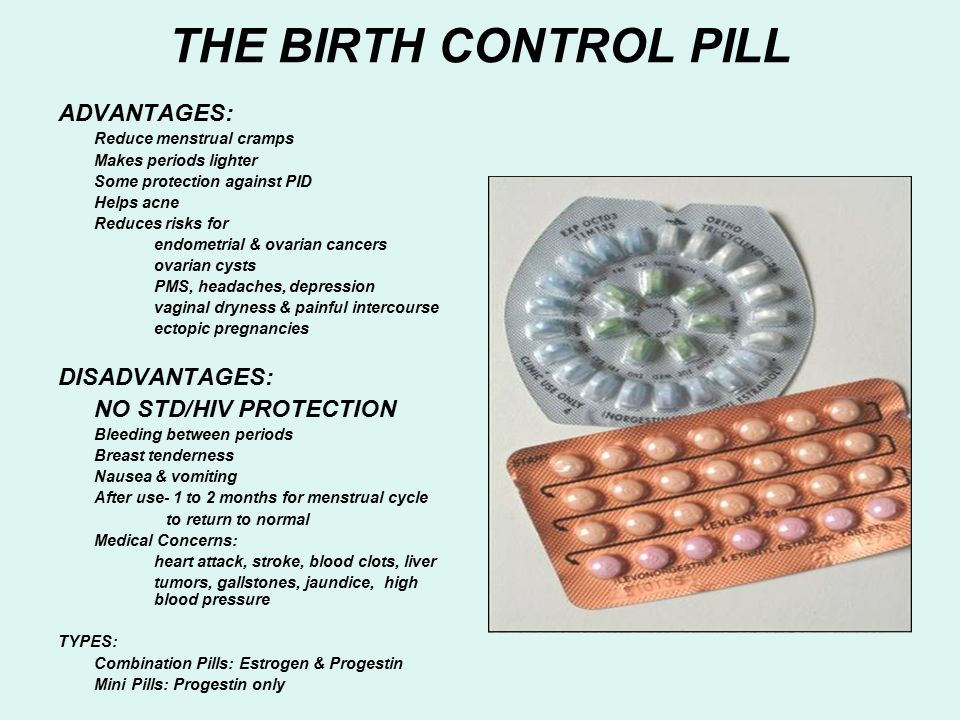

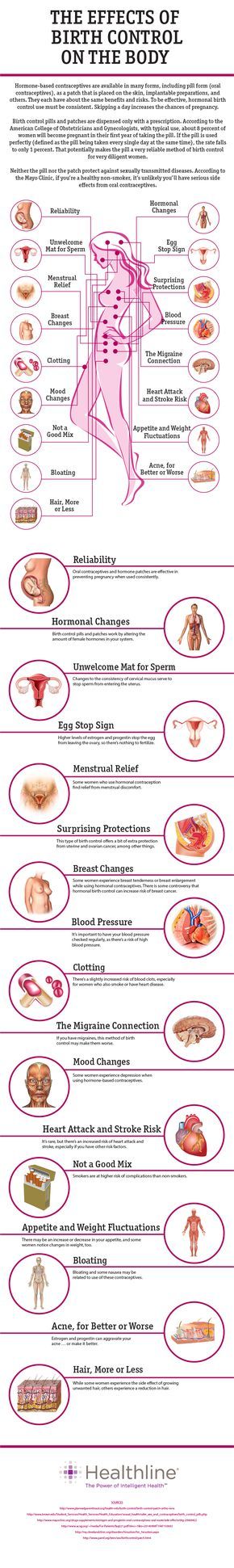

The high efficacy and ease of use of oral contraceptive pills make them very popular. However, there are physical and psychological adverse effects. While the physical risks of the oral contraceptive pill are well established,1 the psychological adverse effects are not as well described.

Oestrogen and progesterone influence neurochemistry, brain function and the activity of neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid, serotonin and dopamine. 2 Oestrogen receptors (ER)- alpha and ER-beta are widely distributed in the brain, with ER-alpha mainly found in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala and brainstem. Progesterone receptors alpha and beta are most abundant in the amygdala, cerebellum, cortex, hippocampus and hypothalamus.

2 Oestrogen receptors (ER)- alpha and ER-beta are widely distributed in the brain, with ER-alpha mainly found in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala and brainstem. Progesterone receptors alpha and beta are most abundant in the amygdala, cerebellum, cortex, hippocampus and hypothalamus.

There is evidence to suggest that oestrogen is neuroprotective in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala and brainstem, protecting the brain from neurodegenerative disease, cognitive decline and affective disorders.3-5 Functional brain imaging studies have indicated that oestrogen regulates the activation of brain regions implicated in emotional and cognitive processing such as the amygdala and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.6 In animals, oestrogen has been shown to modulate neurotransmitters including serotonin,7 dopamine8 and noradrenaline in depression,9 as well as adrenocorticotropic hormone.10

Unlike oestrogen, progesterone is not neuroprotective. Progesterone can worsen mood symptoms.11-13 Plausible links include progesterone augmentation of GABA-induced inhibition of glutamate transmission,14 and progesterone increasing the concentrations of monoamine oxidase, resulting in decreased serotonin concentrations.15

Progesterone can worsen mood symptoms.11-13 Plausible links include progesterone augmentation of GABA-induced inhibition of glutamate transmission,14 and progesterone increasing the concentrations of monoamine oxidase, resulting in decreased serotonin concentrations.15

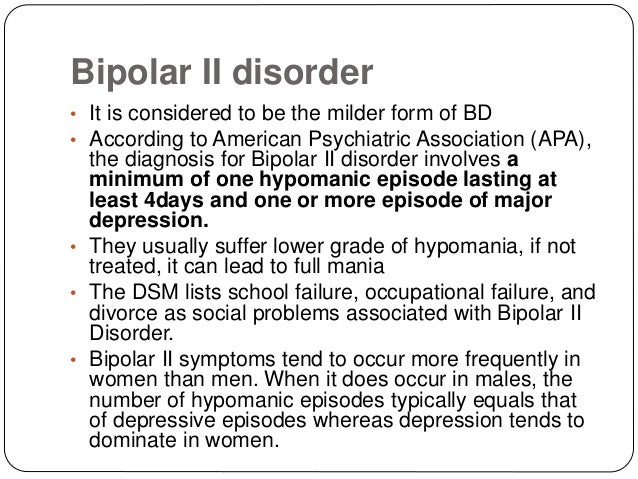

A large study showed a positive association between the use of a levonorgestrel-containing IUD and depression, anxiety and sleep problems in women who did not have these conditions before use of the IUD.16 There are two formulations of progestogen-releasing IUDs, containing 19.5 mg and 52 mg of levonorgestrel. The former may be more tolerable in terms of mood, as it releases small amounts of levonorgestrel. However, there are no data yet on the relationship between its use and the development or exacerbation of depression.

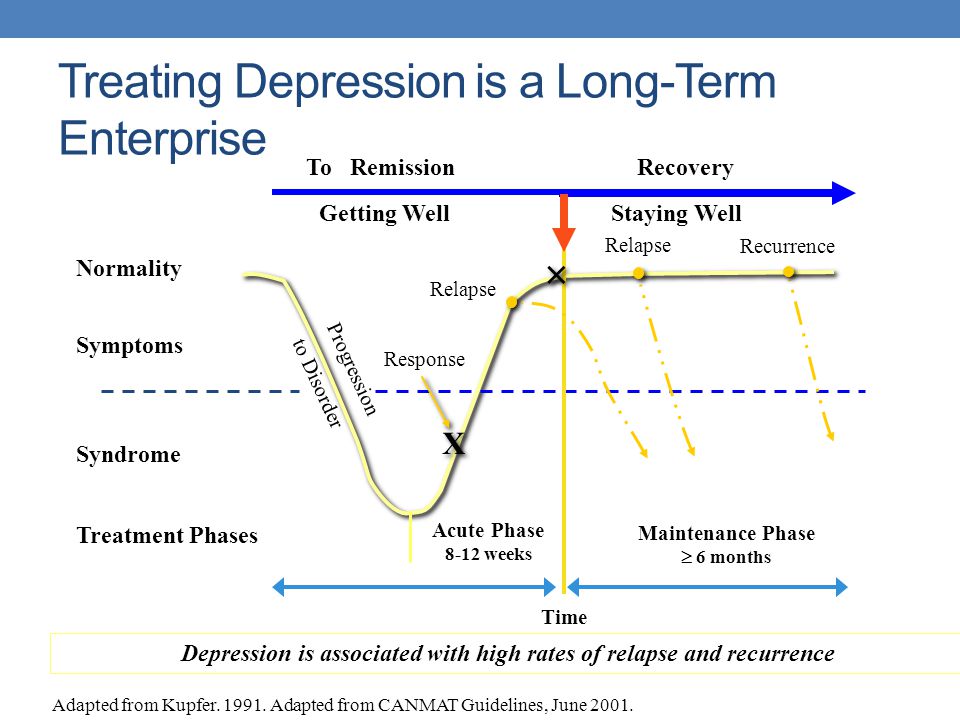

There is evidence to suggest that both oestrogen and progesterone influence brain function, which may be responsible for the negative mood changes and depression commonly reported in women taking oral contraceptive pills. 17-19 One of the most common reasons given for the discontinuation of oral contraceptive pills is changes in mood or an increase in depressive symptoms.20,21 Currently, all oral contraceptive pills may cause mood changes, but the newer oral contraceptive pills containing estradiol or estradiol valerate may be less likely to cause mood changes.

17-19 One of the most common reasons given for the discontinuation of oral contraceptive pills is changes in mood or an increase in depressive symptoms.20,21 Currently, all oral contraceptive pills may cause mood changes, but the newer oral contraceptive pills containing estradiol or estradiol valerate may be less likely to cause mood changes.

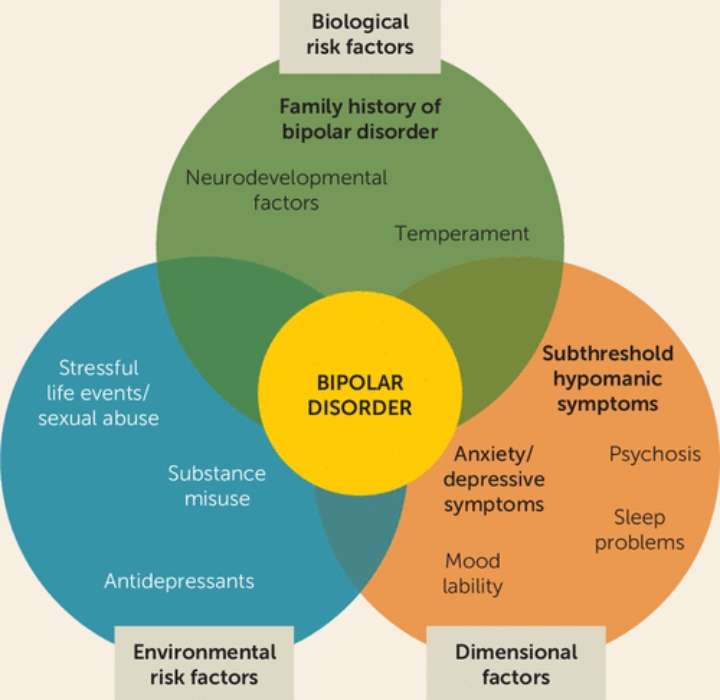

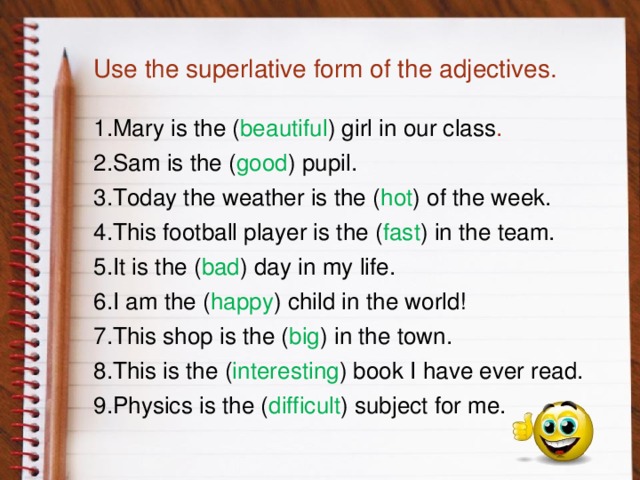

The mechanism underlying how oral contraceptive pills influence mood remains controversial. Nonetheless, there is mounting evidence suggesting a significant relationship between taking oral contraceptive pills and lowered mood and mood disorders such as depression.20,22-25 A comprehensive review published in 2002 included 13 controlled studies investigating the relationship between mood and oral contraceptive pill use.26 All but one study found differences in affect between oral contraceptive pill users and non-users. Another pilot study involving 58 women found that current oral contraceptive pill users or recent users had higher subjective and objective depression rates than those of non-users.27 Moreover, a large Danish study involving more than one million women found an increased risk for first use of an antidepressant and first diagnosis of depression among users of different types of oral contraceptive pills, with the highest rates among adolescents.11 Furthermore, users of medroxyprogesterone acetate, an injectable progestogen contraceptive, reportedly have greater depressive symptoms than those in non-users.17 The link between taking oral contraceptive pills and depression may be attributed to the amount and type of progestogen contained in oral contraceptive pills ().

Another pilot study involving 58 women found that current oral contraceptive pill users or recent users had higher subjective and objective depression rates than those of non-users.27 Moreover, a large Danish study involving more than one million women found an increased risk for first use of an antidepressant and first diagnosis of depression among users of different types of oral contraceptive pills, with the highest rates among adolescents.11 Furthermore, users of medroxyprogesterone acetate, an injectable progestogen contraceptive, reportedly have greater depressive symptoms than those in non-users.17 The link between taking oral contraceptive pills and depression may be attributed to the amount and type of progestogen contained in oral contraceptive pills ().

Table 2

Progestogen and oestrogen content of oral contraceptive pills

| Progestogen | Oestrogen | Quantity* | Brand names |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levonorgestrel (micrograms) | Ethinylestradiol (micrograms) | ||

| 100 | 20 | Femme-Tab ED 20/100, Microgynon 20 ED, Microlevlen ED, Loette, Lenest 20 ED, Micronelle 20 ED | |

| 150 | 30 | Femme-Tab ED 30/150, Levlen ED, Microgynon 30 ED, Monofeme, Nordette, Evelyn 150/30 ED, Eleanor 150/30 ED, Micronelle 30 ED, Lenest 30 ED | |

| 125 | 50 | Microgynon 50 ED | |

| 50 75 125 | 30 40 30 | 6 tablets 5 tablets 10 tablets | Logynon ED, Trifeme, Triphasil, Triquilar ED |

| Norethisterone (micrograms) | Ethinylestradiol (micrograms) | ||

| 500 | 35 | Brevinor, Norimin | |

| 1000 | 35 | Brevinor-1, Norimin-1 | |

| 500 1000 500 | 35 35 35 | 7 tablets 9 tablets 5 tablets | Improvil 28 Day, Synphasic 28 |

| Desogestrel (micrograms) | Ethinylestradiol (micrograms) | ||

| 150 | 30 | Marvelon 28, Madeline | |

| Gestodene (micrograms) | Ethinylestradiol (micrograms) | ||

| 75 | 30 | Minulet | |

| Drospirenone (mg) | Ethinylestradiol (micrograms) | ||

| 3 | 20 | Yaz, Yaz Flex | |

| 3 | 30 | Isabelle, Petibelle, Yasmin | |

| Cyproterone acetate (mg) | Ethinylestradiol (micrograms) | ||

| 2 | 35 | Brenda-35 ED, Carolyn-35 ED, Diane-35 ED, Estelle-35 ED, Jene-35 ED, Juliet-35 ED, Laila-35 ED | |

| Dienogest (mg) | Ethinylestradiol (micrograms) | ||

| 2 | 30 | Valette | |

| Dienogest (mg) | Estradiol valerate (mg) | ||

| 0 2 3 0 0 | 3 2 2 1 0 | 2 tablets 5 tablets 17 tablets 1 tablet 2 tablets | Qlaira |

| Nomegestrol acetate (mg) | Estradiol (mg) | ||

2. 5 5 | 1.5 | Zoely | |

Open in a separate window

* For products with multiple phases of active ingredients

Given that there is a link between hormonal contraception and negative mood or depression, caution must be taken in women who have a personal or family history of depression. However, oral contraceptive pills may provide relief from depressive symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder by stabilising the fluctuations in hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal steroid production.28,29 In this disorder, the regular use of an active oral contraceptive pill (without seven days of placebo pills) has an antidepressant effect.

Currently, all available oral contraceptive pills affect mood. We have shown that nomegestrol acetate (1.5 mg) with 17-beta estradiol (2. 5 mg) is better tolerated by women with mood disorders.30 Our pilot study was a single-site clinical follow-up study that assessed the tolerability and subjective mood response to nomegestrol acetate 17-beta estradiol. Based on a sample of 49 women, we showed that women report a positive mood response and reduced self-reported overall DASS-21 score after taking nomegestrol acetate with 17-beta estradiol compared to previously used oral contraceptive pills.30 Future research with a larger sample is required.

5 mg) is better tolerated by women with mood disorders.30 Our pilot study was a single-site clinical follow-up study that assessed the tolerability and subjective mood response to nomegestrol acetate 17-beta estradiol. Based on a sample of 49 women, we showed that women report a positive mood response and reduced self-reported overall DASS-21 score after taking nomegestrol acetate with 17-beta estradiol compared to previously used oral contraceptive pills.30 Future research with a larger sample is required.

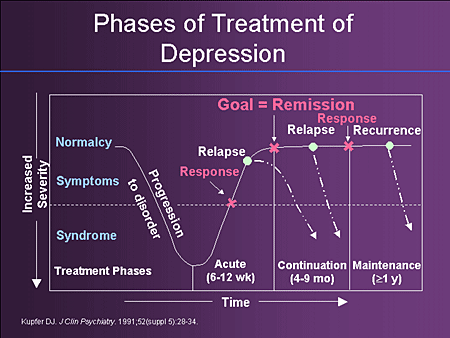

Nomegestrol acetate with 17-beta estradiol is a monophasic preparation with an extended regimen of 24 active pills followed by four placebo pills. The drug can cross the blood–brain barrier, interact with serotonin receptors and regulate cerebral blood flow to the amygdala, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and many other areas of the brain involved in depression.31 Women who develop depression soon (usually between 4 and 12 weeks) after taking other oral contraceptive pills (especially older oral contraceptive pills) may better tolerate nomegestrol acetate with 17-beta estradiol. This is consistent with its successful use in clinical practice for the off-label treatment of mood symptoms associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder.30

This is consistent with its successful use in clinical practice for the off-label treatment of mood symptoms associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder.30

The initial decision for prescribing involves a discussion with a woman to determine her preference. The woman’s age, general health, past contraceptive use and experience, and reliability in terms of daily pill adherence are usually discussed. The woman’s mental health should be discussed in detail in view of links between depression and some contraceptives. This is often ignored and unfortunately can lead to poor outcomes in women.32 Any history of premenstrual depression or depression related to previous contraception should be carefully noted.

Progestogen-only contraceptives should be used with caution in women with current or past depression.11 However, if there is a major contraindication for oestrogen-containing contraceptives, a low-dose progestogen IUD or barrier contraceptives may be options.

Healthcare practitioners must recognise the impact of gonadal hormones on mental health and validate their patients’ observations, thus promoting a good therapeutic relationship. Weight gain and depression appear to be the main issues that drive changing oral contraceptives. Outcomes are likely to improve with shared decision making for the trial of a particular contraceptive, noting that a change may need to be made after approximately three months. Poor outcomes can occur when practitioners deny a woman’s observed relationship between depression, anxiety symptoms and the oral contraceptive.

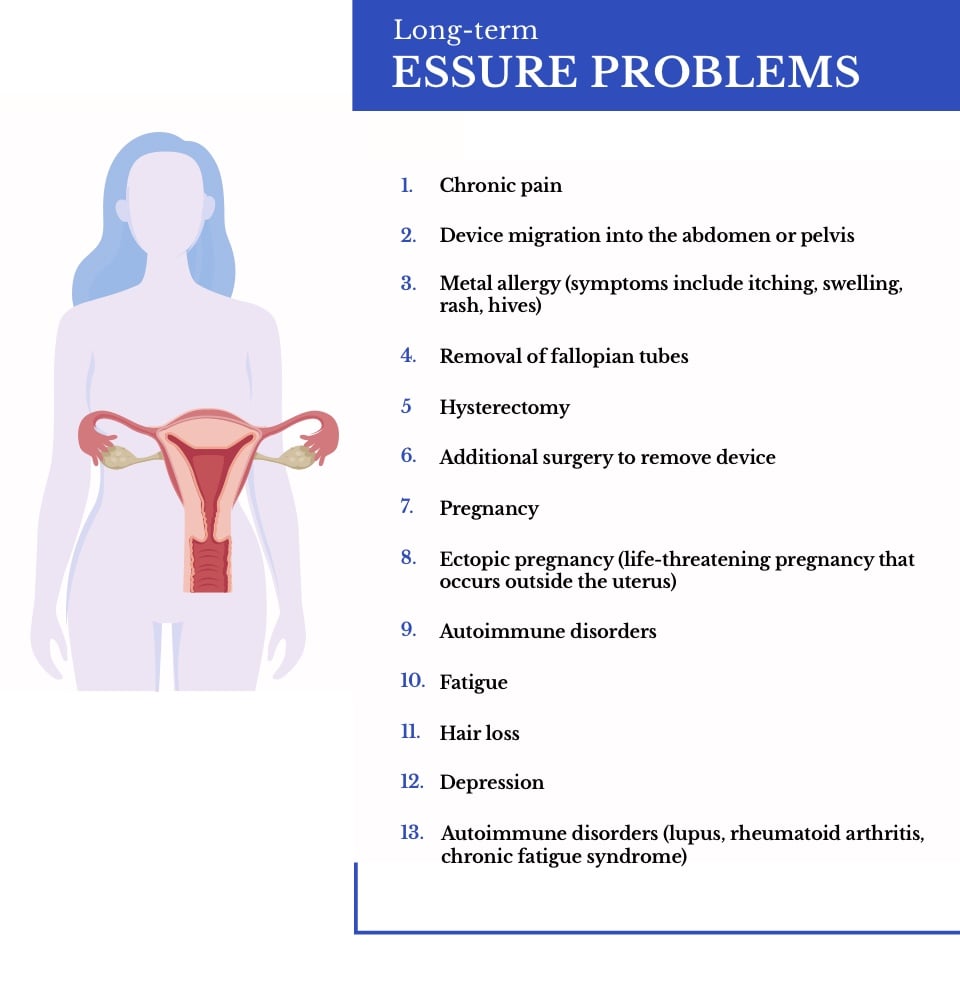

General community education and better information are urgently needed for primary healthcare practitioners regarding the relationship between oral contraceptive pills and depression. Progestogen-only contraception () seems to create a greater propensity for depressive disorders in vulnerable women. Further research is required to determine why some women experience hormone contraceptive-precipitated depression and anxiety, while many women taking hormone contraceptives do not experience mental health issues. It is critical for clinicians to consider the history given by many women of a clear temporal relationship between starting or using a hormone contraceptive and the development of new or worsened depression. In such cases, exploring different types of contraceptives, including barrier methods, is an important patient-validating and therapeutic discussion.

It is critical for clinicians to consider the history given by many women of a clear temporal relationship between starting or using a hormone contraceptive and the development of new or worsened depression. In such cases, exploring different types of contraceptives, including barrier methods, is an important patient-validating and therapeutic discussion.

Conflicts of interest: none declared

1. Rosenberg MJ, Meyers A, Roy V. Efficacy, cycle control, and side effects of low- and lower-dose oral contraceptives: a randomized trial of 20 micrograms and 35 micrograms estrogen preparations. Contraception 1999;60:321-9. 10.1016/S0010-7824(99)00109-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Green L, O’Brien P, Panay N, Craig M. Management of premenstrual syndrome. BJOG 2017;124:e73-105. 10.1111/1471-0528.14260 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Garcia-Segura LM, Azcoitia I, DonCarlos LL. Neuroprotection by estradiol. Prog Neurobiol 2001;63:29-60. 10.1016/S0301-0082(00)00025-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Behl C, Manthey D. Neuroprotective activities of estrogen: an update. J Neurocytol 2000;29:351-8. 10.1023/A:1007109222673 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Behl C, Manthey D. Neuroprotective activities of estrogen: an update. J Neurocytol 2000;29:351-8. 10.1023/A:1007109222673 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Kulkarni J. Oestrogen and neuroprotection. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2011;45:604. 10.3109/00048674.2011.583218 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Toffoletto S, Lanzenberger R, Gingnell M, Sundström-Poromaa I, Comasco E. Emotional and cognitive functional imaging of estrogen and progesterone effects in the female human brain: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014;50:28-52. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.025 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Biegon A, McEwen BS. Modulation by estradiol of serotonin receptors in brain. J Neurosci 1982;2:199-205. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-02-00199.1982 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Chavez C, Hollaus M, Scarr E, Pavey G, Gogos A, van den Buuse M. The effect of estrogen on dopamine and serotonin receptor and transporter levels in the brain: an autoradiography study. Brain Res 2010;1321:51-9. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.093 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Brain Res 2010;1321:51-9. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.093 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Montemayor ME, Clark AS, Lynn DM, Roy EJ. Modulation by norepinephrine of neural responses to estradiol. Neuroendocrinology 1990;52:473-80. 10.1159/000125631 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Young EA, Altemus M, Parkison V, Shastry S. Effects of estrogen antagonists and agonists on the ACTH response to restraint stress in female rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001;25:881-91. 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00301-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Skovlund CW, Mørch LS, Kessing LV, Lidegaard Ø. Association of hormonal contraception with depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73:1154-62. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2387 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Lewis A, Hoghughi M. An evaluation of depression as a side effect of oral contraceptives. Br J Psychiatry 1969;115:697-701. 10.1192/bjp.115.523.697 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Grant EC, Pryse-Davies J. Effect of oral contraceptives on depressive mood changes and on endometrial monoamine oxidase and phosphatases. BMJ 1968;3:777-80. 10.1136/bmj.3.5621.777 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Effect of oral contraceptives on depressive mood changes and on endometrial monoamine oxidase and phosphatases. BMJ 1968;3:777-80. 10.1136/bmj.3.5621.777 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Smith SS, Waterhouse BD, Chapin JK, Woodward DJ. Progesterone alters GABA and glutamate responsiveness: a possible mechanism for its anxiolytic action. Brain Res 1987;400:353-9. 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90634-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Klaiber EL, Broverman DM, Vogel W, Peterson LG, Snyder MB. Individual differences in changes in mood and platelet monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity during hormonal replacement therapy in menopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1996;21:575-92. 10.1016/S0306-4530(96)00023-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Slattery J, Morales D, Pinheiro L, Kurz X. Cohort study of psychiatric adverse events following exposure to levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices in UK general practice. Drug Saf 2018;41:951-8. 10. 1007/s40264-018-0683-x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1007/s40264-018-0683-x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Civic D, Scholes D, Ichikawa L, LaCroix AZ, Yoshida CK, Ott SM, et al. Depressive symptoms in users and non-users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Contraception 2000;61:385-90. 10.1016/S0010-7824(00)00122-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Sanders SA, Graham CA, Bass JL, Bancroft J. A prospective study of the effects of oral contraceptives on sexuality and well-being and their relationship to discontinuation. Contraception 2001;64:51-8. 10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00218-9 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Kulkarni J. Depression as a side effect of the contraceptive pill. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2007;6:371-4. 10.1517/14740338.6.4.371 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Herzberg BN, Draper KC, Johnson AL, Nicol GC. Oral contraceptives, depression, and libido. BMJ 1971;3:495-500. 10.1136/bmj.3.5773.495 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Robinson SA, Dowell M, Pedulla D, McCauley L. Do the emotional side-effects of hormonal contraceptives come from pharmacologic or psychological mechanisms? Med Hypotheses 2004;63:268-73. 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.02.013 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Do the emotional side-effects of hormonal contraceptives come from pharmacologic or psychological mechanisms? Med Hypotheses 2004;63:268-73. 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.02.013 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Abraham S, Luscombe G, Soo I. Oral contraception and cyclic changes in premenstrual and menstrual experiences. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2003;24:185-93. 10.3109/01674820309039672 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Walker A, Bancroft J. Relationship between premenstrual symptoms and oral contraceptive use: a controlled study. Psychosom Med 1990;52:86-96. 10.1097/00006842-199001000-00007 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Oinonen KA, Mazmanian D. Effects of oral contraceptives on daily self-ratings of positive and negative affect. J Psychosom Res 2001;51:647-58. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00240-9 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Joffe H, Cohen LS, Harlow BL. Impact of oral contraceptive pill use on premenstrual mood: predictors of improvement and deterioration. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:1523-30. 10.1016/S0002-9378(03)00927-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:1523-30. 10.1016/S0002-9378(03)00927-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Oinonen KA, Mazmanian D. To what extent do oral contraceptives influence mood and affect? J Affect Disord 2002;70:229-40. 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00356-1 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Kulkarni J, Liew J, Garland KA. Depression associated with combined oral contraceptives--a pilot study. Aust Fam Physician 2005;34:990. [cited 2022 May 1] Available from: https://www.racgp.org.au/ afp/backissues/2005/4886 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Nyberg S. Mood and physical symptoms improve in women with severe cyclical changes by taking an oral contraceptive containing 250-mcg norgestimate and 35-mcg ethinyl estradiol. Contraception 2013;87:773-81. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.09.024 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Watson NR, Studd JW, Savvas M, Garnett T, Baber RJ. Treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome with oestradiol patches and cyclical oral norethisterone. Lancet 1989;2:730-2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90784-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Lancet 1989;2:730-2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90784-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Robertson E, Thew C, Thomas N, Karimi L, Kulkarni J. Pilot data on the feasibility and clinical outcomes of a nomegestrol acetate oral contraceptive pill in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:704488. 10.3389/fendo.2021.704488 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Rubinow DR, Girdler SS. Hormones, heart disease, and health: individualized medicine versus throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Depress Anxiety 2011;28:282-96. 10.1002/da.20810 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Hall KS, Steinberg JR, Cwiak CA, Allen RH, Marcus SM. Contraception and mental health: a commentary on the evidence and principles for practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:740-6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Can hormonal birth control trigger depression?

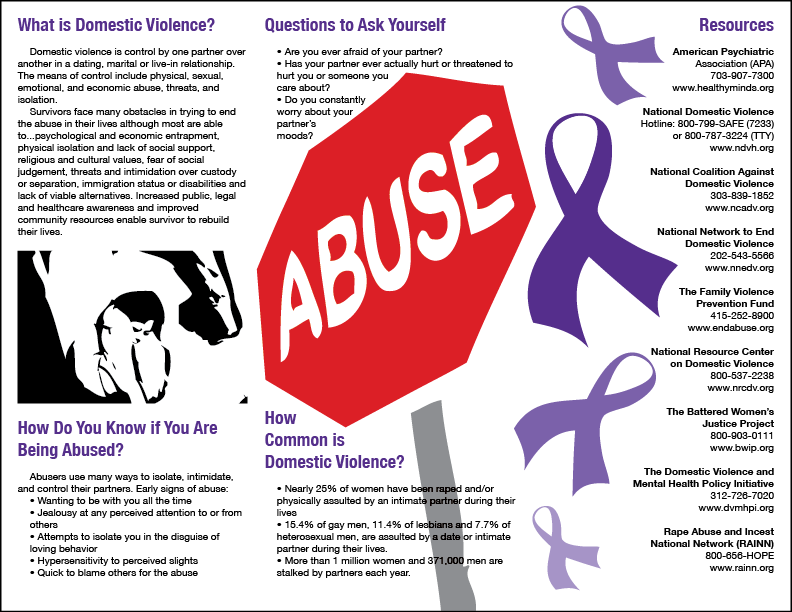

Over the years, more than a few patients in my women’s health practice have told me that their hormonal birth control — the pill, patch, ring, implant, injection, or IUD — made them feel depressed. And it’s not just my patients: several of my friends have felt the same way. And it’s not just me who has noticed this; decades of reports of mood changes associated with these hormone medications have spurred multiple research studies.

While many of these did not show a definitive association, a critical review of this literature revealed that all of it has been of poor quality, relying on iffy methods like self-reporting, recall, and insufficient numbers of subjects. The authors concluded that it was impossible to draw any firm conclusions from the research on this birth control and depression.

A strong study on hormonal birth control and depression

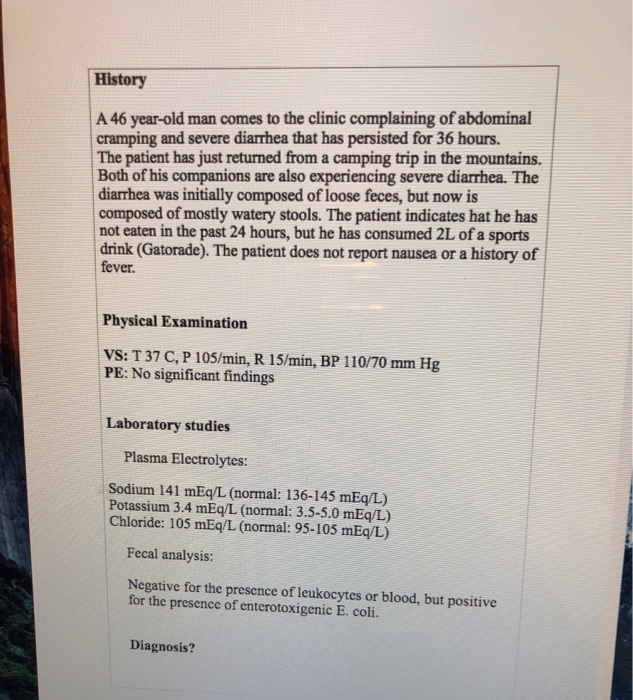

However, another does meet the criteria to qualify as high-quality, and therefore believable. The study of over a million Danish women over age 14, using hard data like diagnosis codes and prescription records, strongly suggests that there is an increased risk of depression associated with all types of hormonal contraception.

The authors took advantage of Denmark’s awesome nationalized information collection systems, including diagnosis and prescribing data. These exist because the country has had a well-run and organized national health system for decades. They have reams of data on every single person in Denmark going back to the 1970s. Additional available information used in this study included education level, body mass index, and smoking habits. All of this was de-identified to protect the individuals involved, so there was no potential violation of privacy.* Surprising connections between hormonal birth control and depression emerged.

This study looked at women aged 15 to 34 between 2000 and 2013, and excluded those with preexisting psychiatric conditions, as well as those who could not be prescribed hormones due to medical issues like blood clots, and those who would be prescribed these medications for other reasons. They also excluded women during pregnancy and for six months after pregnancy, and recent immigrants. This way they wouldn’t accidentally include women with an unrecorded history of any of these conditions.

This way they wouldn’t accidentally include women with an unrecorded history of any of these conditions.

The researchers analyzed hormonal contraceptive use and subsequent depression in two different ways. They evaluated women who had received a diagnosis of depression as well as women who had received a prescription for antidepressants; these analyses were run separately, and they obtained statistically equivalent results.

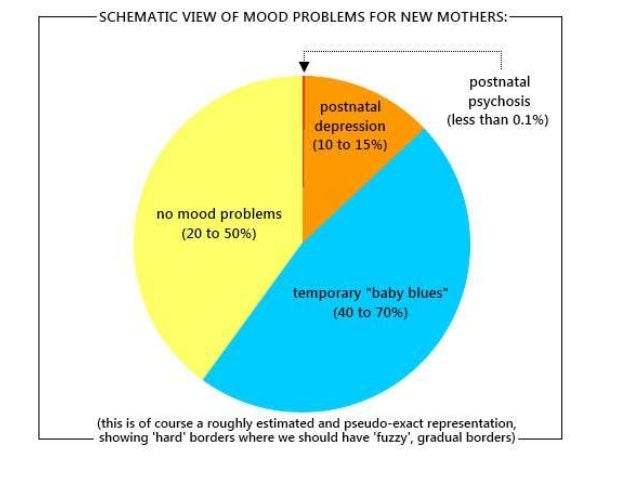

Risk of depression with hormonal birth control, small but real

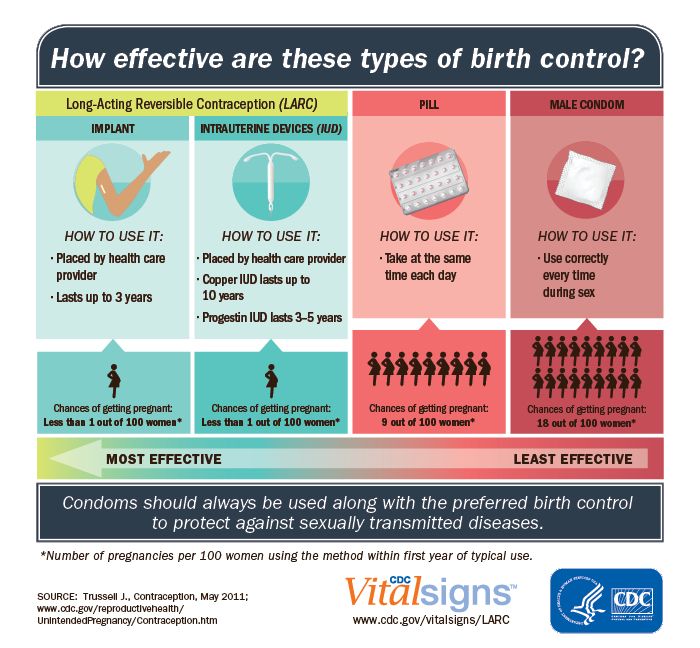

All forms of hormonal contraception were associated with an increased risk of developing depression, with higher risks associated with the progesterone-only forms, including the IUD. This risk was higher in teens ages 15 to 19, and especially for non-oral forms of birth control such as the ring, patch and IUD. That the IUD was particularly associated with depression in all age groups is especially significant, because traditionally, physicians have been taught that the IUD only acts locally and has no effects on the rest of the body. Clearly, this is not accurate.

Clearly, this is not accurate.

Should we stop prescribing hormonal birth control? No. It’s important to note that while the risk of depression among women using hormonal forms of birth control was clearly increased, the overall number of women affected was small. Approximately 2.2 out of 100 women who used hormonal birth control developed depression, compared to 1.7 out of 100 who did not. This indicates that only some people will be susceptible to this side effect. Which ones, we don’t know. But I plan to discuss this possibility with every patient when I’m counseling them about birth control, just as I would counsel about increased risk of blood clots and, for certain women, breast cancer. In the end, every medication has potential risks and benefits. As doctors, we need to be aware of these so we can counsel effectively.

*My medical researcher mind is boggled: all this information collected on every single citizen makes quality research studies like this easily possible. We can’t even dream of conducting such an inclusive study like this here in the United States, where yes, all these data are collected, but exist haphazardly scattered across medical offices, hospitals, and insurance companies. Most of a U.S. researcher’s funding and efforts here go into collecting subjects and data. Compared to what the Danish have, what a waste of time!

We can’t even dream of conducting such an inclusive study like this here in the United States, where yes, all these data are collected, but exist haphazardly scattered across medical offices, hospitals, and insurance companies. Most of a U.S. researcher’s funding and efforts here go into collecting subjects and data. Compared to what the Danish have, what a waste of time!Swallowing tablets. How are birth control pills related to depression?

Treatment

MedicineCondomsSex

29 November 2018

Independent

The serious mental illness side effects of oral contraceptives have been featured in a new BBC documentary by Olivia Petter. AIDS.CENTER publishes the translation.

Birth control pills have been controversial since they appeared in the UK in 1961 years old.

Despite existing research linking their use to breast cancer, blood clots, decreased libido and weight gain, they remain the most popular form of contraception, with over a hundred million women worldwide taking them.

At the same time, a large body of research shows a strong correlation between the use of birth control pills and the development of psychiatric disorders, and a new BBC Two documentary sheds light on the severity of the problem, showing how taking them has driven some women to depression and suicidal thoughts.

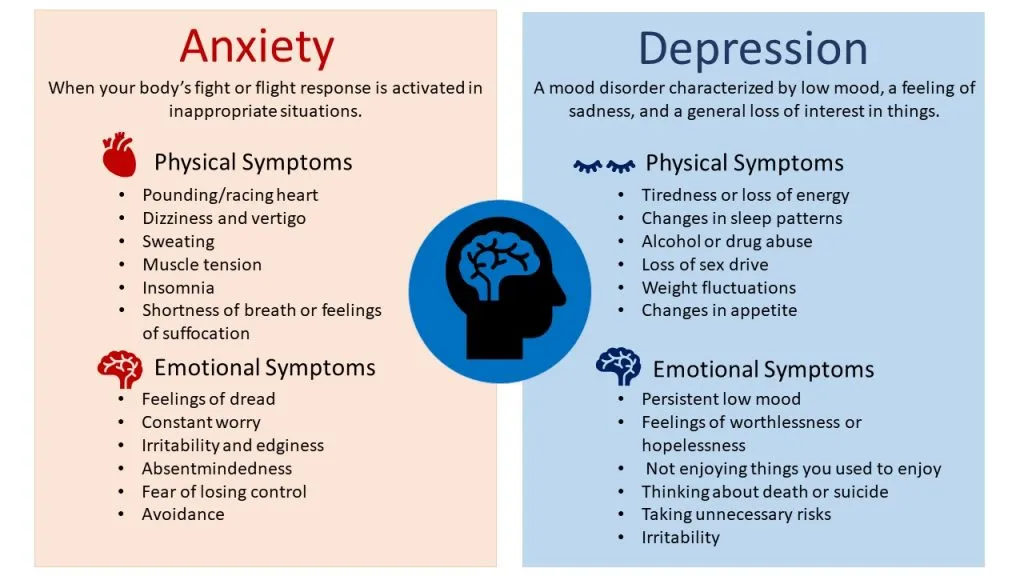

The hormone progesterone contained in pills (both contraceptive and mini-pill) is associated by scientists with the development of mental complications: depression, anxiety, mood deterioration.

However, researchers have yet to find an ethical way to prove causation, because such studies would have to include a placebo control group, which can lead to unwanted pregnancies, which in turn raises many moral complexities.

The BBC data gathering group conducted a survey that read: "Contraceptive pills: how safe are they?" The results showed that one in four women who took the pill reported negative effects on their mental health.

related

Prevention

Spit in the mouth of a frog, eat a bee: The history of contraception since ancient times

- Condoms Sex

One of these women is Danielle, she is 31 years old. In an episode titled "Horizon," she recalls how the side effects were "terrible and debilitating," clarifying that she never had any mental health problems before starting birth control. “I went from normal to suicidal in just 6 months,” she adds.

In an episode titled "Horizon," she recalls how the side effects were "terrible and debilitating," clarifying that she never had any mental health problems before starting birth control. “I went from normal to suicidal in just 6 months,” she adds.

Grazia Editor-in-Chief Vicky Spratt had a similar experience and recalls how her mental health began to deteriorate soon after starting birth control when she was 14 years old. This led her to depression and regular panic attacks.

"I remember thinking, 'If this is what the rest of my life is going to be like, I don't want to live like this,'" Spratt, 30, says in the documentary.

Spratt is now scheduled to take antidepressants and undergo cognitive behavioral therapy, but she explains that no doctor has linked her worsening mental state to birth control.

After extensive research on the Internet, she found several research materials linking depression to birth control. Vicki decided to take a break from her appointment to see if her condition would improve. Bottom line: She began to feel better “in just a few weeks.”

Bottom line: She began to feel better “in just a few weeks.”

In the BBC story, Spratt talks to Copenhagen professor Øyvind Lidegaard, who has access to a unique database of medical records—in Denmark, each patient's data is entered into a centralized system. This allowed him to observe the recordings of more than a million Danish women aged 15 to 34 over a period of sixteen years and to conduct two studies on the relationship between mental health and hormonal contraception.

related

Prevention

“There is no sex in the USSR”: A review of Soviet condoms

- HIVCondomsPrevention

One study showed that women taking contraceptives, whether combined drugs or drugs based on progesterone alone, are more likely to be prescribed antidepressants than those who do not take birth control. The difference is especially noticeable among women aged 15 to 19 who take combination drugs.

Another study links hormonal contraceptive use to suicide attempts and suicide. Lidegard's research is supported by a separate study from Sweden covering over 800,000 women, which was published in March 2018.

Despite the number of women experiencing mental health problems due to birth control, Spratt notes that too little has been done in the UK to combat this problem. This is due to a lack of data and the apparent reluctance of the UK National Health Service (NHS) to take action to correct the situation.

She has been studying the link between the birth control pill and mental illness for almost two years and after several inquiries, she found out that this is not an area where the NHS has any data at all.

This means that the NHS does not monitor women who take oral contraceptives and are treated for mental disorders at the same time, at least not to the extent that the Danish medical system does.

The paper also concludes that women may not be fully informed about these side effects before starting treatment - without any mention of depression or anxiety disorders. Instead, leaflets distributed to women at sexual health clinics only mention "mood changes" as a possible side effect.

Instead, leaflets distributed to women at sexual health clinics only mention "mood changes" as a possible side effect.

“What does that even mean? It could mean anything,” Spratt says in an interview with The Independent. “I think the NHS has become attached to 'mood swings' because they're worried that stopping birth control could cause a huge spike in unwanted pregnancies. It surprises me that despite the known link between progesterone and depression, the NHS doesn't even look into it and as a result we don't know anything about how many women in the UK experience these side effects."

related

Treatment

Will it help? How safe is sex with antiseptics? She is convinced that research and data must be collected so that doctors can properly inform women about the potential risks of taking birth control pills.

Physician Zoe Williams explains that all medications have potential side effects, but the story of birth control is a bit different because it is taken by perfectly healthy women, not those who want to prevent or cure a disease.

“Therefore, side effects that significantly affect quality of life in a negative way are unacceptable,” she concludes. “Especially when there are so many types of pills and alternative methods of contraception.”

Subscribe to the AIDS.CENTER channel in Yandex.Zen

MedicineCondomsSexlet's be friends?

- read

- read

- join

- read

read also

Society"The child was my anchor." The path from dissidence to equal consultants

- HIVWomenStigma

Fund activitiesWithout syringes and frightening pictures: what social advertising about HIV should be like

- HIVCharityFund activitiesArtStigma

Society“We must act despite the anxiety.” Interview with the famous St.

Petersburg psychiatrist Anton Kostin

Petersburg psychiatrist Anton Kostin - DepressionChildrenMedicinePsychiatryPsychology

The connection between birth control pills and depression has not been proven

Image copyright, BSIP

Image caption,Some of the side effects of birth control pills have been well known since they were on the market in the 1960s

One scientific study recently postulated an association between birth control pills and risk of depression .

This is not the first study purporting to find unwanted side effects of birth control pills.

But, as Elisabeth Kassin writes, an illiterate interpretation of statistics poses a much greater danger to women's health.

According to the World Health Organization, more than 100 million women worldwide use combined oral contraceptives, also known as birth control pills.

Some of the side effects of these tablets have been well known since they were introduced to the market in the 1960s. But a recent study allegedly established a link between birth control pills and depression.

Danish scientists examined the medical records of more than a million women aged 15 to 34 who had never suffered from depression in the past.

They found that those who took birth control pills were more likely to be prescribed antidepressants or diagnosed with depression later on by doctors.

The results of the study were reported in the press around the world. "Do you take birth control pills? You are more likely to be depressed: women who take contraceptives are 70% more likely to suffer from depression," one newspaper loudly declared. "Contraceptive pills are associated with depression. Why didn't a scandal erupt?" asked another.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Birth control pill randomized trial impossible

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

However, as Phil Hannaford of the University of Aberdeen points out, the Danish study showed only "a small effect, if any."

Of every 100 women not taking birth control pills, 1.7 were using antidepressants. Among every 100 women taking oral contraceptives, this number is slightly higher - 2.2.

According to Hannaford, this is a very small difference. "The difference is 0.5, which is one woman in every 200," he says.

Although these data indicate a statistical relationship, they do not say anything about a causal relationship, as some other factors may be at work in this case.

"For example, some of the women who take birth control pills may have separated from their partners. This, in turn, can lead to depression," he notes.

This, in turn, can lead to depression," he notes.

Such studies are sufficient to suggest a hypothesis, but we should not forget that they do not provide evidence for a causal relationship, adds Phil Hannaford.

This requires a large randomized controlled trial in which one group of women is given the test substance and another is given a placebo.

In this case, this is not possible (and unethical) because women who receive a placebo would think they are taking contraceptives and would not take other steps to prevent conception.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Birth control pills from the 70s

This is not the first time scientists have been talking about the possible side effects of birth control pills.

Rare cases of blood clots, which can be life-threatening, attract the most attention.

But a poor understanding of the degree of risk can lead to undesirable consequences.

Professor Gerd Gigerenzer of the Harding Center for Risk Literacy in Berlin says that “There are many traditions in the UK, including scaring people about the risks associated with birth control pills. lead to thrombosis.

In 1995, the British Medicines Safety Board issued an official warning, citing a study showing third-generation birth control pills "doubled the risk of thrombosis".

"The alarm has gone off all over the country," says Prof. Gigerenzer.

As a result of this panic, some women stopped taking contraceptives. According to some estimates, this led to an increase in the birth rate by 12,400 babies in 1996 and 13,600 additional abortions.

"This is an example of a lack of risk literacy - not understanding the difference between relative and absolute risk leads to an emotional reaction, which in turn leads to negative consequences for the women themselves," he says.

Image copyright, SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Image caption,Pregnancy and childbirth lead to thrombosis more often than the birth control pill

What is the absolute risk? And how should women understand it?

The Guardian recently published a film about young women who died of blood clots after taking hormonal contraceptives - birth control pills, vaginal rings and patches.

The authors of the film argue that if women knew about the mortality rate, they would stop using hormonal contraceptives. They also state that out of 10,000 women who use vaginal rings, at least a few die.

"It's not certain that a few out of 10,000 women will die," says Dr Sarah Hardman of the Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

"It would be more accurate to say that a few out of 10,000 women - between five and 12 - will develop thrombosis. But not all of them will die from this. In fact, only about 1% of women who develop thrombosis die" she says.

"We are talking about the fact that three to 10 out of every million women die due to blood clots resulting from the use of hormonal contraception," - emphasizes Hardman.

For women of reproductive age who do not use hormonal contraceptives, only two out of 10,000 women per year face a fatal outcome.