Ocd without compulsion

Pure O: An Exploration into a Lesser-known Form of OCD

Pure Obsessional OCD (Pure-O) is a type of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) in which an individual reports experiencing obsessions without outwardly observable compulsions.

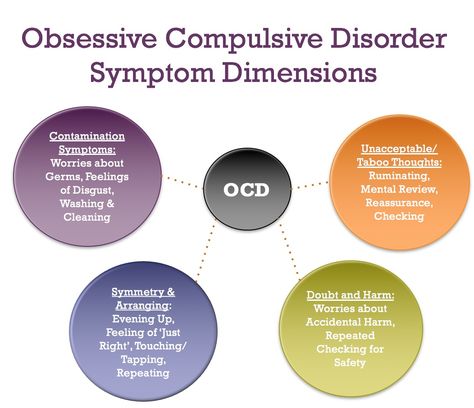

Pure-O obsessions often manifest as intrusive, unwanted, inappropriate thoughts, impulses or “mental images.” The compulsions for Pure-O mainly exist in the form of mental rumination and reassurance seeking. Intrusive thoughts and images tend to coalesce around specific themes including: safety and harm thoughts about self and others, worries about sexual orientation (Sexual Orientation OCD or Homosexuality OCD), worries about relationship decisions (ROCD), fears of doing something illegal, pedophilia (POCD), over-concern for honesty or religious purity, or existential fears.

It is important to distinguish Pure-O from a singular fleeting thought. All humans experience unwanted thoughts. However, non-clinical persons, or those who do not have OCD, are able to easily dismiss the thoughts as uncomfortable, weird, or just something their brain does. What distinguishes Pure-O from a fleeting unwanted thought is the anxiety that becomes affixed to these thoughts which then creates a significant amount of distress to the sufferer.

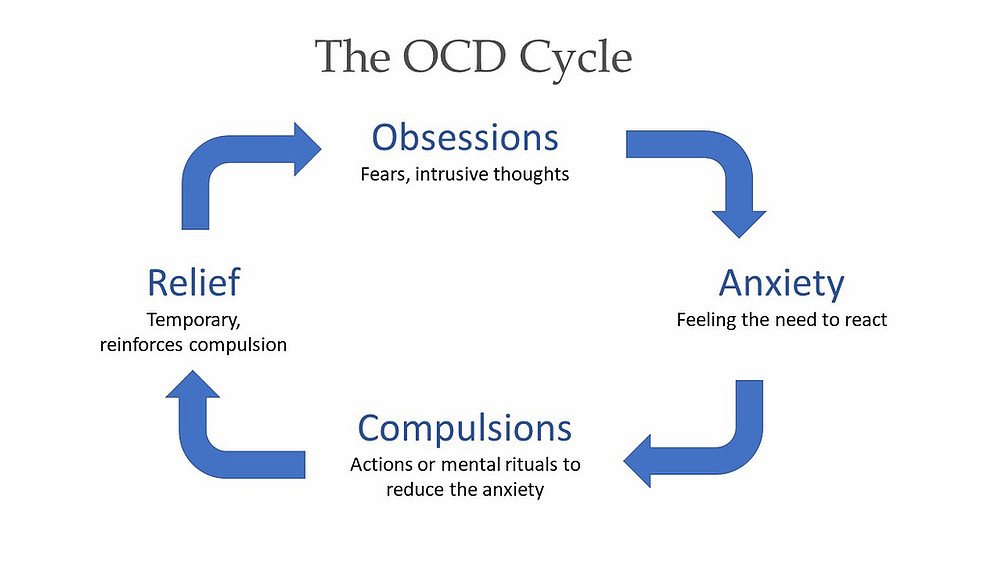

Pure-O sufferers often report that their thoughts make them incredibly anxious and they can’t get them out of their head. Thus, what ignites the symptoms of Pure-O is not the experience of intrusive thoughts but actually one’s reaction to them. The more one dislikes experiencing the intrusive thoughts and tries to repress, control, or fight the thoughts, the greater the frequency of intrusive thoughts one will experience. It is the very act of trying to not to have a bothersome thought that guarantees its resurfacing.

Pure-O is rooted in the faulty assumption that humans have control over their thoughts, which we do not. The human brain has evolved to be constantly spinning around, trying to find interesting problems to solve, and to search for threats to our safety or existence. The brain is particularly interested in thoughts that contain uncertainty.

When a Pure-O sufferer’s brain lands on a thought or question that is unacceptable to the person having the thought, the fear network of the brain is alerted that something is wrong and needs to be done about it IMMEDIATELY. This fight or flight experience is what causes the sufferer a great deal of distress.

Many people with Pure-O may also experience comorbidity with features of perfectionism. Pure-O sufferers tend to maintain a high overall standard for what their brain “should” be thinking and the level of control one should have over their thoughts. Individuals living with Pure-O will commonly make assumptions including, “I shouldn’t be thinking this,” “These thoughts are wrong or bad,” or “I should be able to control my thoughts.”

They spend time analyzing why they are having these thoughts and what the thoughts say about them as a person. For many sufferers of Pure-O, failing to meet this standard of control over their own brain will lead them to conclude that they are a bad person or a monster, and they are not.

There are many sub-types of Pure-O. Some sufferers may experience one theme that plagues them incessantly, whereas others may experience themes that rotate around. The next section of this article will elaborate on several common sub-types of Pure-O.

COMMON PURE-O SUBTYPES

Pedophilia OCD (pOCD) encompasses unwanted thoughts, images, and urges related to sexual attraction toward or molestation of children. An individual struggling with pOCD struggles with the doubt and shame related to the question of “Am I a pedophile?”

The following are typical examples of pOCD:

- A woman is changing her niece’s diaper and worries that she may have intentionally grazed by her niece’s vagina or is hyper-focused on the baby’s nether regions. She responds by quickly changing the diaper or asking her sister to do it for her.

- A woman who works with children suddenly gets flooded with images of one of her students performing oral sex on her. She calls out sick from work for the rest of the week so as to not see this student which will provoke more unwanted images.

- A man is sitting on the subway and feels a groinal response after noticing a young girl. He looks away and tries to shut down his groinal response.

- A woman is sitting next to a young boy on the bus and assesses how she feels in comparison to being touched by her husband.

- A man is spending the day at the beach with his family when a pre-pubescent girl walks by in a bathing suit. He attempts to figure out if he was examining her body in a sexual way.

- A man is watching a popular television show and notices that one of the underage characters is pretty. He feels this is perverted and tells himself that he is a monster for having this thought. He now avoids watching this show and other shows with children in them.

- A woman feels an increase in vaginal lubrication while hugging her son. Disgusted by this response, she shames herself and limits physical contact with her family.

- A young man is watching pornography when he suddenly becomes unsure if the girl is 18.

He drills a hole through his computer, throws the computer in the water and refuses to go anywhere near a pornography website.

He drills a hole through his computer, throws the computer in the water and refuses to go anywhere near a pornography website. - A man is bouncing his daughter on his lap when he feels a groinal movement. Convinced that this means he is a pedophile, he immediately stops and tries to figure out what it all means, reading articles about pedophiles and trying to determine if he shares characteristics with them.

Harm OCD is a term used to describe obsessive thoughts, images, urges and impulses related to harm towards oneself or others.

The target of these thoughts can be family members, friends, anyone close to you, or even complete strangers. The most prototypical manifestation of Harm OCD is the individual who hides all the knives in the house so that they don’t act on their fear and impulsively stab family members.

As with all spike themes, Harm OCD does not indicate anything about the OCD sufferer or their penchant for violence. Having violent images does not increase the likelihood that you will engage in violent behavior.

Additional examples of Harm OCD include:

- A man has an image of pushing an obnoxious person standing in front of him into the oncoming subway tracks. Fearing that this image means that he may actually do it, he considers previous episodes when he has had violent thoughts or acted violently and he moves 10 feet away from this person.

- A legal gun-owner experiences violent thoughts about his wife. He responds to these images by storing all guns in a gun safe that only his wife has the combination to rather than continue to carry the guns with him as he normally would.

- A woman has an urge to strangle her husband while hiking. Noting that noone is around to stop her, she requests to terminate the hike. She avoids hiking from this point forward and pesters her husband with questions regarding his thoughts on her potential to strangle people.

- A teenager notices that he is feeling somewhat down that day. He begins to fear that he may become even more depressed and commit suicide by jumping out of the window.

He compulsively thinks as many “happy thoughts” as possible in order to ensure that he won’t end his life.

He compulsively thinks as many “happy thoughts” as possible in order to ensure that he won’t end his life. - A man experiences an urge to stab his son. Worrying that he may lose his mind and act on this urge, he considers turning himself into the police so that he can ensure that this will not happen.

- A woman is driving with a friend when she observes an intrusive thought about impulsively driving into a tree. She pulls the car over and asks her friend to take over.

- A man has an image of shooting a child while driving to work. He responds by taking a different route to work, one that avoids all playgrounds, parks and schools where children may be present.

- A new mother becomes preoccupied with the fear of causing harm to the innocent baby. She requests that her husband give all baths to the baby to ensure that she can’t drown the baby.

Sexual orientation obsessions in OCD (SO-OCD), also commonly referred to as HOCD, or “homosexual OCD,” is a specific type of OCD that involves extreme anxiety surrounding worries about sexual orientation.

Common SO-OCD obsessions include worries about experiencing an unwanted change in sexual orientation (i.e. fear of becoming gay), fears that others may think one is gay, or fears that one has hidden same-sex desires.

As with all spike themes, SO-OCD does not indicate anything about the OCD sufferer or their sexual preference. Having intrusive thoughts and/or images about the same sex does not increase the likelihood that one will engage in homosexual behavior or ‘come out’.

Additional examples of SO-OCD include:

- A college aged woman suddenly catches a glimpse of her roommate changing her clothes. Suddenly, she is flooded with thoughts of whether or not she was attracted to her roommate’s naked body. She checks her vagina for signs of arousal and actively avoids looking at her roommate in the future out of fear it will provoke more unwanted thoughts.

- A man is walking down the street and notices that another man is attractive. During the rest of his walk to work he avoids looking at any other strangers.

When he arrives at the office, he immediately searches on google and on various blogs for topics on sexuality, including ‘how do you know if you are gay?’

When he arrives at the office, he immediately searches on google and on various blogs for topics on sexuality, including ‘how do you know if you are gay?’ - A newlywed woman worries that her thoughts of becoming gay must mean that she will have to leave her spouse. She asks her husband constantly for reassurance regarding whether he thinks she is straight and also compulsively researches information on the internet about ‘how to know if/when you are coming out?’

- A young man is sitting with his legs crossed and has the thought, "What if crossing my legs this way makes people think I'm gay?" He ruminates on what his friends may be thinking about him and what other behaviors he may be engaging in that may be similarly perceived.

- A woman repeatedly has the thought, "What if I have been unconsciously gay all along and I just don't know it yet?" She avoids certain neighborhoods where people who are gay hang out. She also avoids all television shows, movies, and media that contain any homosexual/homosexuality references.

Relationship OCD, also commonly referred to as ROCD, is another form of Pure-O in which the sufferer experiences intrusive, unwanted, and distressing thoughts about their feelings of attraction, attachment, and love for their partner. Obsessions in ROCD include a preoccupation with doubting the relationship or whether their spouse is ‘the one,’ and/or doubting the overall level of attractiveness, sexual desirability, or long-term compatibility. Obsessions often arise in otherwise entirely healthy relationships.

As with all forms of OCD, compulsions are performed in an effort to reduce the individual’s anxiety related to their unwanted obsessional thoughts and intense discomfort with uncertainty. Frequently, ROCD behavior revolves around the obsession “what if I don’t really love/or are attracted to my partner.”

ROCD is often misdiagnosed by mental health treatment providers who simply don’t have a solid grasp of the complexities of OCD and all of its variations. As a result, many therapists frequently misread the symptoms of ROCD as a sign of “relationship issues”, rather than as evidence of ROCD.

As a result, many therapists frequently misread the symptoms of ROCD as a sign of “relationship issues”, rather than as evidence of ROCD.

Many clinicians and practitioners who are not properly trained with Pure-O may suggest that “maybe you’re just not that into him” or suggest that the person “may not be right for you” or “not the one” or “you should really listen to your doubts” which often leads the ROCD sufferer into a panic.

Many people have a difficult time understanding the difference between ROCD and more typical relationship doubts. For individuals suffering with ROCD, doubts about their relationship are usually ego-dystonic, which simply means that their doubts are inconsistent with their feelings. Many people doubt their relationships from time to time, but they are not tortured by these thoughts. The core issue with ROCD is not intimacy, but intolerance of uncertainty. Being afraid to commit to another person is not the same as ROCD.

Some examples of ROCD include:

- A married woman who has the obsessional thought, “What if I don’t really love my partner?” She looks at old pictures and mentally recites her wedding vows until she feels right about him.

- A young man is drawn to the shape of his girlfriend’s chin and obsesses whether or not he finds her attractive enough to be with her or whether he should break up with her. The thoughts of both leaving and staying cause the man significant anxiety and he compares his girlfriend with other girls he sees on the street to look for evidence of sufficient feelings.

- A woman knows that her boyfriend is about to propose and she worries whether or not he is “the one” and tries to figure out through mentally replaying different scenarios of a possible engagement to see if she is going to feel the right way when he pops the question.

- A young man is attracted to a girl he notices on the street and begins to obsess that it must mean that he doesn’t love his girlfriend and that he must be in the wrong relationship. The young man becomes very upset because he does not want to have to break up with her.

- A girl who is living with her boyfriend confesses that there are times when she feels turned off by the thought of intimacy or sex with her partner.

She believes that if she is not “100% attracted to him 100% of the time,” then this must be proof that she is in the wrong relationship.

She believes that if she is not “100% attracted to him 100% of the time,” then this must be proof that she is in the wrong relationship. - A husband imagines cheating on his partner and fears that because he had these thoughts that he must secretly want to be with someone else.

As previously discussed, OCD and non-OCD sufferers can experience any of these unwanted thoughts at any time. The qualifying difference is that the OCD sufferer experiences a debilitating level of anxiety in association with the presence of these thoughts and the notion of tolerating the uncertainty around the answer to a particular “what if” question: “What if I am gay?” “What if I’m a pedophile?” “What if I do not love my spouse?” OCD sufferers often make the faulty assumption that they ‘should’ be able to control their thoughts and that the thoughts ‘should’ not be there. Secondly, the OCD sufferer thinks that because the recurring thoughts are present, “they must mean something” about the sufferer. Thus, begins the analysis (mental compulsions) and quest to prove or disprove (undo) the intrusive thought in order to attempt to gain an answer to the question and seek relief from the anxiety.

Thus, begins the analysis (mental compulsions) and quest to prove or disprove (undo) the intrusive thought in order to attempt to gain an answer to the question and seek relief from the anxiety.

As the quest for seeking certainty begins, OCD sufferers aim to prove that they are not what their brain is telling them they already are or could become. Spikes related to Harm OCD, pOCD, ROCD, and SO-OCD can overpower an individual to obsess and ruminate about past, current, or future thoughts, images, or responses. Past situations are replayed over and over in the attempt to find clues or gather facts that can help resolve the incessant doubting related to thoughts of whether or not the sufferer is going to cause harm, is a pedophile, is in the wrong relationship or is attracted to the same sex. Mental rumination within ROCD may include: trying to figure out whether they feel ‘the right way’ towards their partner, researching on the internet about relationships and love.

This mental rumination can cause a significant impairment to sufferers and distract them from conversations, from focusing at work, or from spending time with family. Everything else pales in comparison to the urgency that the OCD presents and the fraudulent remedy it presents through rumination. Eventually, this can lead to isolating behavior and depression. This effort to seek certainty through mental rumination is ineffective and only serves to empower the threatening message.

Everything else pales in comparison to the urgency that the OCD presents and the fraudulent remedy it presents through rumination. Eventually, this can lead to isolating behavior and depression. This effort to seek certainty through mental rumination is ineffective and only serves to empower the threatening message.

Avoidance

Another tactic that Pure-O sufferers attempt to employ is to avoid people or situations that may provoke their intrusive thoughts, and in turn, try to reduce the experience of anxiety. For example, a pOCD sufferer may walk an indirect route to work in order to avoid schools, playgrounds, or parks. They may keep their eyes down at all times or turn off the TV when there are children or adolescents on the screen. Avoidance behavior is extremely powerful and reinforcing as it prevents individuals from having to confront the horrors of pOCD in that moment. Hiding scissors and knives is a common avoidance ritual for the Harm OCD sufferer.

Many individuals with SO-OCD and ROCD will abstain from dating altogether in an effort to steer clear of these intrusive thoughts. Avoiding becoming sexually aroused ensures that unwanted thoughts and images can not present during vulnerable sexual activity. SO-OCD sufferers will often prefer to abstain from sexual activity to resist comparing groinal responses in appropriate or inappropriate situations. Individuals with Pure O are mostly aware of their avoidance behavior but choose to avoid over the arduous notion of confronting their fears.

Avoiding becoming sexually aroused ensures that unwanted thoughts and images can not present during vulnerable sexual activity. SO-OCD sufferers will often prefer to abstain from sexual activity to resist comparing groinal responses in appropriate or inappropriate situations. Individuals with Pure O are mostly aware of their avoidance behavior but choose to avoid over the arduous notion of confronting their fears.

As people with OCD make decisions to avoid potential triggers, their lives become more guided by their anxiety than their true desires. They often find themselves giving up on things or relationships that could otherwise bring them joy.

Reassurance Seeking

As with all forms of OCD, reassurance seeking is prevalent within Pure-O as it is geared towards absolving the anxiety, guilt and shame that has become all consuming.

Reassurance seeking is common in the form of looking up answers online, in books or through asking loved ones questions. These questions can seem arbitrary, nonsensical and incessant; however, family members, spouses or friends will often try to answer them repeatedly in an attempt to help the OCD sufferer.

For example, Harm OCD sufferers often ask parents to recall any potential violent episodes from childhood. Sharing the nature of the spike with loved ones feels like it helps to ensure their safety.

Questions may relate to how others perceive the OCD sufferer. An individual with pOCD may ask a loved one if they think the individual with Pure-O is a pedophile or they may ask questions aimed at ensuring that nothing fishy has happened in the past. ROCD sufferers typically compare their relationship to other relationships in an effort to reassure themselves that they really do love their partner. Reassurance can be sought by probing the Internet for information on whether they have made the “right” choice in a partner.

SO-OCD can compel someone to Google “How do I know if I’m gay?” or to read coming out stories seeking reassurance of their sexual orientation. SO-OCD sufferers may ask a spouse, friends or family for reassurance as to their sexual orientation.

Treatment

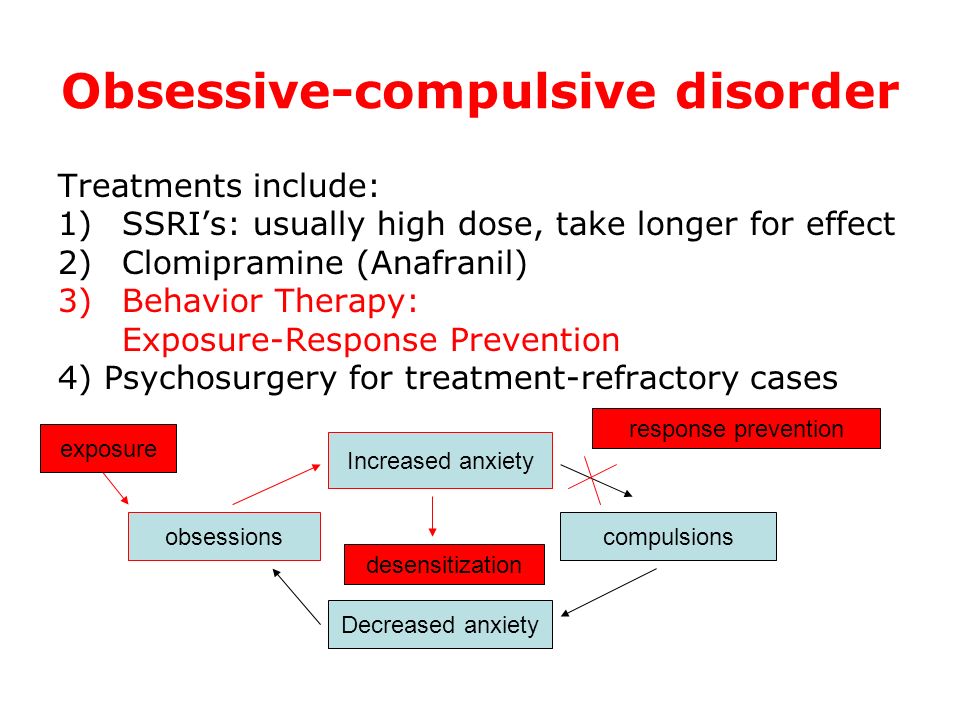

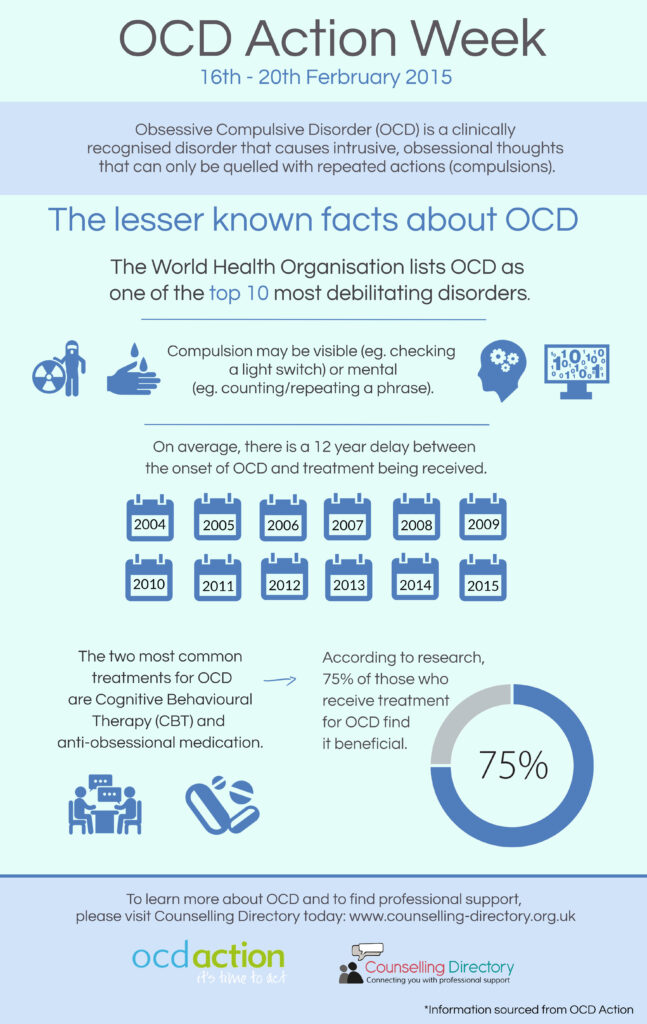

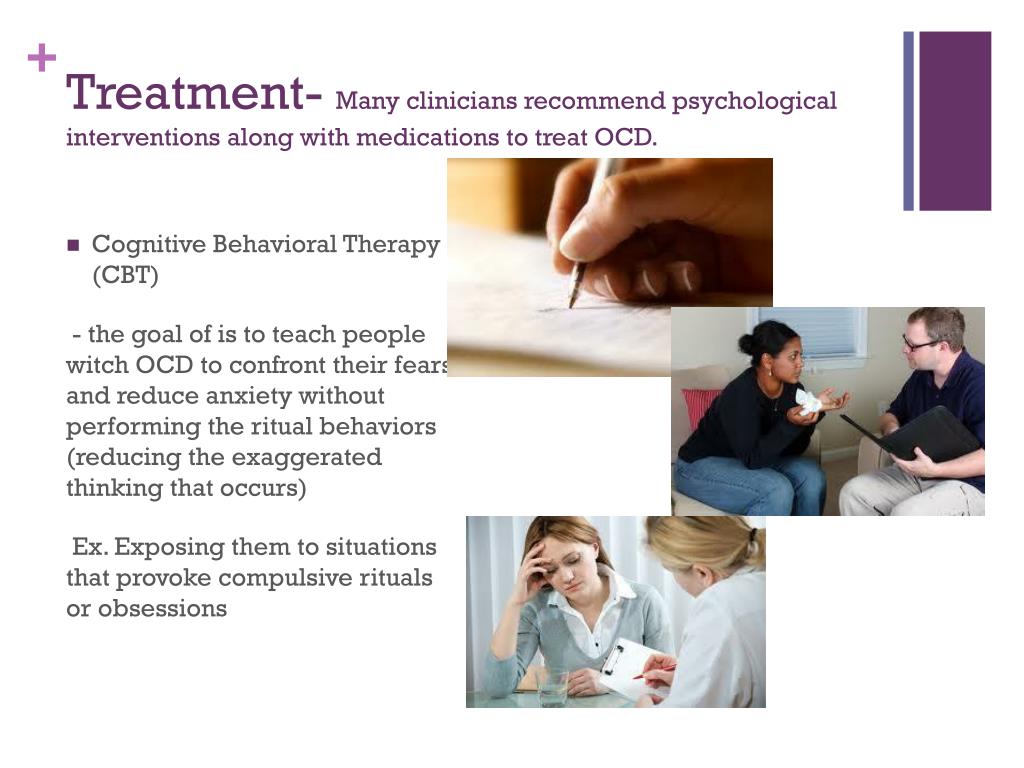

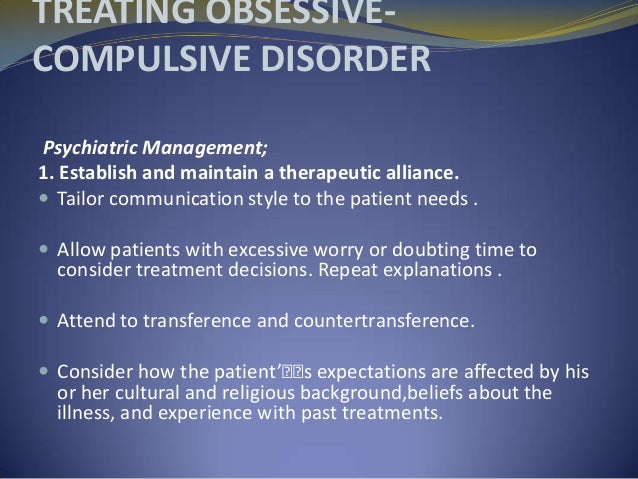

Treatment for Pure-O has improved dramatically over the past twenty years. Advances in the field of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) have led to the development of a therapeutic approach that is remarkably effective in treating OCD. This treatment, called Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP, EX/RP, or “exposure therapy”) has dramatically altered the therapeutic management and has consistently been found by researchers to be the most effective treatment for OCD. But unfortunately, for the sufferer, there is no way to get past OCD without going through it.

Advances in the field of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) have led to the development of a therapeutic approach that is remarkably effective in treating OCD. This treatment, called Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP, EX/RP, or “exposure therapy”) has dramatically altered the therapeutic management and has consistently been found by researchers to be the most effective treatment for OCD. But unfortunately, for the sufferer, there is no way to get past OCD without going through it.

ERP entails intentionally facing your fear directly by provoking unwanted, distressing thoughts and images while simultaneously resisting the urge to seek relief. In addition to ERP, medications such as selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be helpful in the treatment of Pure-O.

For Pure-O, rather than attempting to feel in control by engaging in a torturous and endless search for certainty, the treatment entails facing the fear and uncertainty directly and decisively. This can feel like an immense, if not, impossible challenge to undertake for someone who spends so much time trying to feel better by getting rid of OCD. Just as people with OCD can doubt that they have OCD, it is common to also doubt whether Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) will be effective. But it is.

Just as people with OCD can doubt that they have OCD, it is common to also doubt whether Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) will be effective. But it is.

ERP usually begins by creating a fear hierarchy. The therapist will most often begin by collaborating with the client on choosing a lesser anxiety-provoking challenge, that allows the client to gain confidence and experience in the therapy methodology. Eventually, the client will progress to more difficult exposures as they grow emotional tolerance to their fears of uncertainty.

ERP can be compared to the process of getting allergy shots. By exposing patients to tiny amounts of whatever it is they are allergic to and increasing the amounts of allergen in each injection gradually over time, the body builds up a tolerance. With ERP, the body is building up a tolerance to anxiety.

Through consistently and repeatedly engaging in anxiety-provoking exposure exercises, an individual living with Pure-O can begin to habituate to the anxiety-provoking thoughts and images, rendering them irrelevant. Similar to jumping into a freezing cold pool and experiencing shock at first, your body eventually gets used to the temperature and you don’t notice the cold. In line with habituation, it is critical that an OCD sufferer chooses to remain in intensely uncomfortable situations. Eventually, an individual in treatment can learn that they are not a victim of their OCD by demonstrating to themselves that they can tolerate anxiety. This empowering message helps to build a sense of freedom and choice in the battle against OCD.

Similar to jumping into a freezing cold pool and experiencing shock at first, your body eventually gets used to the temperature and you don’t notice the cold. In line with habituation, it is critical that an OCD sufferer chooses to remain in intensely uncomfortable situations. Eventually, an individual in treatment can learn that they are not a victim of their OCD by demonstrating to themselves that they can tolerate anxiety. This empowering message helps to build a sense of freedom and choice in the battle against OCD.

Successful therapy outcomes are directly related to the OCD sufferer’s ability to sacrifice short-term relief-seeking behavior in exchange for long-term mental liberation from Pure-O. Many patients quip that this is “easier said than done” and they are correct in asserting that engaging in EX/RP feels like an impossible challenge. Despite this understandably defeatist attitude, when one accepts uncertainty without trying to seek relief, mastery of OCD is achieved.

Dr. Jordan Levy is a licensed clinical psychologist in private practice in Manhattan and in Livingston, New Jersey. He specializes in the treatment of Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder including violent and sexual obsessions.

Dr. Jan Weiner is a licensed clinical psychologist in private practice in New York, New York. She specializes in the treatment of Anxiety Disorders and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder including Pure-O.

About the author

Dr. Jordan Levy is a licensed psychologist in private practice in Manhattan at the Center for Cognitive-Behavioral Psychotherapy and in Livingston, New Jersey. He specializes in the treatment of anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder including the Purely-Obsessional subtype (Pure-O). He can be reached by email at [email protected] or online at www.DrJordanLevy.com.

Dr. Jan Weiner is a Made of Millions advisory board member and licensed clinical psychologist who practices in New York City. She specializes in the treatment of anxiety disorders and OCD, including Pure O. Learn more about her work at www.drjanweiner.com.

Learn more about her work at www.drjanweiner.com.

Pure OCD Symptoms and Treatment

What is Pure OCD?

Pure obsessional obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a subtype of OCD that’s characterized by intrusive thoughts, images or urges without any visible physical compulsions. Pure OCD differs slightly from other types of OCD because its compulsions primarily take place in a person’s head rather than actions.

Though they can take many forms, these intrusive thoughts generally center on themes of harm, relationships, sexuality and religious or moral questions. These ideas and images can feel like an attack on a person’s sense of self and they often come with guilt and shame. That’s where the mental compulsions come in: to help people cope with those thoughts. (It is possible to have pure OCD and experience no compulsions at all — but this is a rarer form of the subtype.)

Many people with pure OCD are terrified of sharing these experiences for fear of being judged. It’s common for people with pure OCD to feel like they are the only ones dealing with this. Because their experience is internal, there often aren’t obvious visual clues an outside observer might notice to identify someone with pure OCD, but that makes it no less distressing.

It’s common for people with pure OCD to feel like they are the only ones dealing with this. Because their experience is internal, there often aren’t obvious visual clues an outside observer might notice to identify someone with pure OCD, but that makes it no less distressing.

Pure OCD symptoms

Although it might sound surprising, it is relatively common to have a disturbing or immoral thought, impulse or urge — regardless of OCD diagnosis. The difference is, for people without OCD, these thoughts tend to last only a few seconds and don’t cause significant distress. A person may be driving and suddenly think to themselves, “What would happen if I drove off this bridge?” But they’ll shortly dismiss the idea and move on.

For someone with pure OCD, these intrusive thoughts can be frequent and highly distressing. They will identify with this thought and feel convinced it reveals something about who they are as a human being. They might think, “I just had a thought of harming someone — that means I must be a violent person. ”

”

For someone with pure OCD, it can feel impossible to disassociate from these thoughts. The experience can feel so real, they can’t imagine their thoughts are actually from OCD. Someone with pure OCD may want to prove or disprove one of their intrusive thoughts (for example: “I would never drive off a bridge, but how can I know for sure?”). This doubt then latches on to anything that feels even remotely uncertain. A person with pure OCD may even doubt their diagnosis. They might think, “Maybe this time, my thoughts actually mean I want to hurt someone.”

Examples of pure OCD obsessions

People with pure OCD experience unwanted obsessive thoughts, impulses and urges. Here are some examples of common themes:

- Harm: Jennie is sharpening her pencil in a classroom when she suddenly has the thought, “This pencil is really sharp,” followed by an intrusive image of herself hurting a classmate with the pencil. She may start thinking, “I could actually hurt someone.

I shouldn’t be in this class. I need to leave right now or I could endanger the other classmates.”

I shouldn’t be in this class. I need to leave right now or I could endanger the other classmates.”

- Relationships: Taylor is watching a movie with his partner and thinks, “That’s weird. Why didn’t he laugh at that part? Does he not find it funny?” He might start thinking, “What if we’re not meant to be together? I’ve always found a shared sense of humor really important. Now that I think about it, we have nothing in common.”

- Religion: Francis is attending a religious service and suddenly thinks of something funny. He begins asking himself, “I can’t believe I almost just laughed during Mass. There must be something wrong with me. Should I confess? Am I going to hell?”

- Sexual images: Jules is in the middle of an important meeting when they suddenly experience intrusive images of their manager naked. The images feel so alarming, Jules tries to push them out of their head, but that doesn’t help.

Instead, more images keep popping up.

Instead, more images keep popping up.

Examples of pure OCD compulsions

People with pure OCD engage in mental compulsions (rather than physical ones) in an attempt to alleviate their anxiety. Here are some examples of what that might look like:

- Mental review: Someone with pure OCD may engage in excessive mental review as a way to relieve their anxiety. For example, if Jennie has fears of harming a classmate with her sharp pencil, she might spend the entire class mentally reviewing all the proof she can come up with that she has not gotten out of her chair and stabbed someone. She may decide that she needs to review everything she has done since she entered the classroom over and over again before she can relax. Even though fellow students may see Jennie busily absorbing the lecture material, in her head, she’s reviewing every past interaction with students she can remember. After class is over and Jennie is at home, she might mentally review her day at school, searching for proof that she did not stab anyone and is not a murderer.

- Mental rituals: Someone with pure OCD may create certain mental rituals they must accomplish in order to reassure themselves their intrusive thoughts are untrue, or that they aren’t a bad person. For example, Taylor listens to his partner talk and thinks, “I hate you. Why did I agree to marry you?” This thought is so alarming, he might decide that each time this thought pops into his head, he has to think of five positive qualities about his partner, or else their relationship will fall apart. Taylor might also decide to repeat specific words, images or numbers each time he has a negative thought. He might decide to repeat to himself, “I love my partner,” five times to neutralize a negative thought or think of a photograph where they are at the beach having a great time. Mental ritualscan also include reciting special prayers or mantras in one’s head. For example, Taylor might continually pray that his negative thoughts are removed from his mind. Taylor might also excessively ruminate on his thoughts and what it might mean, without a specific ritual.

- Reassurance Seeking: Someone with pure OCD might also excessively reassure themselves as a way to relieve their anxiety. For example, if Sam has fears of unintentionally embarrassing his wife in public, he might continually say to himself, “I won’t embarrass my wife” or, “I am not an embarrassment and she would tell me if I was.” Sam’s self-reassurance might make him feel better in the moment, but willonly provide temporary reassurance before his obsessions begin again. Further, Sam might have to think the “right” thought which could cause him to be stuck in an unending cycle of trying to prevent his feared outcome from occurring.

Pure OCD treatment: ERP therapy

Even though pure OCD compulsions are often not noticeable from an outside perspective, they are best treated like all types of OCD compulsions — with exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy. ERP is considered the gold standard for OCD treatment; 80% of people with OCD experience positive results from therapy. The majority of patients see results within 12 to 25 sessions.

The majority of patients see results within 12 to 25 sessions.

As part of ERP therapy, you’ll track your obsessions and compulsions and make a list of possible ways to face your fears. You’ll work with your therapist to slowly put yourself into situations that bring on your obsessions and the accompanying anxiety or discomfort. Exposures will be mindfully created so that you’re gradually building toward your goal rather than moving too quickly and getting completely overwhelmed.

For pure OCD, a trained ERP therapist will be able to spot your mental compulsions and be able to work with you to come up with the best course of treatment for exposures to them.

The idea behind ERP therapy is that exposure to these thoughts and the discomfort is the most effective way to treat OCD. When you continually submit to the urge to do compulsions, it only strengthens your need to engage in them. On the other hand, when you prevent yourself from engaging in your compulsions, you teach yourself a new way to respond and will very likely experience a noticeable reduction in your anxiety as you provide yourself with opportunities to change your learning and practice living with uncertainty.

Examples of ERP OCD exposures

If you’ve ever tried not thinking about something, you know how difficult it is to control your thoughts. ERP therapy takes the opposite approach: Instead of trying to make yourself stop your obsessive thoughts, you welcome them.

Let’s say that each time you’re driving, you can’t stop seeing mental images of your car running over a pedestrian. This scene starts appearing in your mind every time you drive past a school or busy street downtown. As a way of coping, you’ve started counting to seven in your head each time you see an image like this. This strategy worked at first, but lately it has been less effective. So, as a way to take extra precaution, you’ve decided to count to 49 instead of seven.

An ERP therapist may ask you to welcome the intrusive image of running over a pedestrian without trying to make it go away. You might think, “Welcome it? No way! That’s terrible. I just want these images to stop.” But instead of trying to suppress them, a therapist may ask you to put your full attention on these thoughts. This teaches your brain a new response to your intrusive thoughts and shows you that they don’t have to keep you from living your life. Eventually, you will begin to distinguish yourself from your OCD thoughts, and it will become easier to let them come and go without engaging in compulsions or avoidance.

This teaches your brain a new response to your intrusive thoughts and shows you that they don’t have to keep you from living your life. Eventually, you will begin to distinguish yourself from your OCD thoughts, and it will become easier to let them come and go without engaging in compulsions or avoidance.

As part of ERP treatment, you may be asked to drive without performing your counting ritual. This will take a gradual approach. For example, if not counting to 49 is too stressful at first, you may start by waiting for 30 seconds before this ritual starts. Then you’d work your way up to two minutes. Eventually, you may find you’re able to experience an intrusive thought with less stress or urges to count.

Once you become more familiar with these thoughts and allow the thoughts to exist without responding via compulsion, they might begin to feel less alarming. By confronting these thoughts without compulsion, you start to learn that their feared outcome won’t occur, that you can manage the outcome if it does occur, and that you can tolerate the anxiety or distress that arises when they have intrusive thoughts. In some cases, people find that their anxiety subsides to the point where they no longer experience intense fears related to their thoughts.

In some cases, people find that their anxiety subsides to the point where they no longer experience intense fears related to their thoughts.

How to get help for Pure O OCD

When pure OCD is untreated, it can take over a person’s ability to think about anything other than their intrusive thoughts and lead to isolation from others and a sense of hopelessness about one’s life. Since there’s no visible evidence of their experience, it’s more common for people with pure OCD to delay treatment for longer than for people with other OCD subtypes.

If you’re struggling with pure OCD, there is help available. To learn more about pure OCD and how it’s treated with ERP, you can schedule a free call with the NOCD clinical team and find out how this type of treatment can help you.

All of our therapists specialize in OCD and receive ERP-specific training and ongoing guidance from our clinical leadership team. Many of them have dealt with OCD themselves and understand how crucial ERP therapy is. NOCD offers live face-to-face video therapy sessions with OCD therapists, in addition to ongoing support on the NOCD telehealth app, so that you’re fully supported during the course of your treatment. You can also join our PURE OCD community and get 24/7 access to personalized self-management tools built by people who have been through OCD and successfully recovered.

NOCD offers live face-to-face video therapy sessions with OCD therapists, in addition to ongoing support on the NOCD telehealth app, so that you’re fully supported during the course of your treatment. You can also join our PURE OCD community and get 24/7 access to personalized self-management tools built by people who have been through OCD and successfully recovered.

Learn more about pure OCD

- When terrifying thoughts are a sign of pure OCD

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder/OCD in its purest form. Pure OCD treatment

CONSULTATION

online 500 UAH STOP ALARM

7 lessons for 1999 UAH SELF-HYPNOSIS

4 lessons for 1499 UAH STOP SMOKING

session for 999 UAH

UARU

Our specialization is the treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in its purest form and associated anxiety disorders

- Read this article

- What is pure OCD

- Pure obsessive-compulsive disorder - symptoms

- Pure Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Treatment

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Hypnosis

- Individual treatment

- Group treatment

Some people may suffer from "Pure Obsessive/Obsessive OCD" (sometimes also referred to as "Pure OCD"), they say they have obsessions (obsessions) but without being forced into obsessive acts (compulsions) . These obsessions often manifest as intrusive, unwanted thoughts and images as they perform actions that they believe may be harmful, cruel, immoral, sexually perverse, or blasphemous. For people diagnosed with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) in its purest form, these obsessions are so frightening and tormenting because they conflict with their values and beliefs.

These obsessions often manifest as intrusive, unwanted thoughts and images as they perform actions that they believe may be harmful, cruel, immoral, sexually perverse, or blasphemous. For people diagnosed with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) in its purest form, these obsessions are so frightening and tormenting because they conflict with their values and beliefs.

OCD / Pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder - Symptoms

Symptoms in people diagnosed with Pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder can vary widely from person to person. Some examples of obsessions seen in pure OCD are:

- Recurrent thoughts of harm or images of physical assault on one's spouse, parents, children, self, friends, or others (also called "Harming OCD"). ")

- Emerging anxiety that you might run over a pedestrian while driving (also called hit and run OCD)

- Excessive fear that you might inadvertently harm others (for example: setting fire to a house, unintentionally poisoning another person, inadvertently exposing toxic chemicals in an accessible place)

- Persistent fear of child molestation (sometimes called pedophile OCD or POCD)

- An obsessive fear that a person might be homosexual when in fact he or she is not (sometimes called "gay OCD" or "sexual orientation OCD" or "gay OCD" or "GOCD", English "gay ocd" or "sexual orientation OCD" or "homosexual OCD" or "HOCD")

- Recurrent obsessive thoughts that the person doesn't really love their partner, or is with the "wrong" partner (also called "relationship OCD" or "ROCD")

- Intrusive thoughts that a person will say or write something inappropriate to someone, for example, a person will speak obscenely to his employer or write a hateful letter to his friend

- Persistent intrusive thoughts or images that the person considers blasphemous or blasphemous, such as wanting to worship Satan or have sex with Christ

- Recurring fear that a person does not live (think) in accordance with their religion, morality, or ethical values (sometimes called "decency/morality OCD", English "crupulosity OCD")

- Recurrent obsessive thoughts about the appearance of physiological problems with breathing, swallowing, blinking, thoughts that objects in the eyes may begin to “blur”, ringing in the ears, problems with digestion, the appearance of physical sensations in certain parts of the body, etc.

(sometimes called sensorimotor OCD, sensorimotor OCD, or psychosomatic OCD)

(sometimes called sensorimotor OCD, sensorimotor OCD, or psychosomatic OCD)

However, it should be noted that the term "pure OCD" is "in a certain way" a misnomer. Although at first glance it may seem that people suffering from "pure OCD" do not exhibit obsessive/compulsive behaviors, a careful assessment almost always reveals the presence of a variety of compulsive behaviors, behaviors to avoid something, behaviors that a person wants to complete any process, or "mental coercion." These compulsive behaviors/compulsions may not be as easily observed as other more obvious signs/symptoms in people diagnosed with OCD, such as compulsive handwashing and constant checking to see if the person has shut the door or not. But they are compulsive/compulsive actions in response to uncomfortable obsessions. Some common examples of compulsions (obsessive behavior) that are observed in people diagnosed with pure obsessive-compulsive disorder:

- Avoidance of situations in which a person fears, is afraid of unwanted obsessions

- Repeatedly seeking reassurance that the person does not and/or will not do what they consider "wrong" or "bad"

- Compulsive checking of one's own body in order to obtain strong evidence that the person is not sexually attracted to another person whom he/she considers inappropriate, inappropriate (especially observed in cases of "pedophilia OCD", "sexual orientation OCD" and "relationship OCD ")

- Quietly or silently, prays or repeats certain phrases in an attempt to counteract or neutralize, suppress thoughts that he considers immoral or blasphemous

- Performs a behavior trying to make sure no bad things happen (example: counting, snapping fingers, knocking on wood)

- Repeatedly assures other people that he or she had no thoughts/ideas that he or she would consider unacceptable

- Constantly thinking about obsessions, thereby trying to prove to himself that he or she has not done and / or will not do anything that he or she may perceive as “inappropriate” or “wrong”

Pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder/OCD Treatment

Pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder/OCD Treatment using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

For many years it was thought that pure OCD treatment was almost impossible , since only obsessive thoughts, ideas were present, but there was no any compulsive behavior. However, a certain type of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) called Exposure and Response Prevention (EPR) has been shown to be effective when treating people who have pure OCD. Using EPR, patients are trained to face their own fears about certain thoughts, and are trained to actively challenge their compulsive (compulsive/repetitive) behaviors and the avoidance behaviors they used to deal with those thoughts. Another method that has been developed by Cognitive Behavioral Therapy that has proven to be extremely effective is Cognitive Restructuring. As a result of using this method, clients diagnosed with pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder are taught to challenge the validity of their unwanted thoughts that cause them to suffer greatly.

However, a certain type of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) called Exposure and Response Prevention (EPR) has been shown to be effective when treating people who have pure OCD. Using EPR, patients are trained to face their own fears about certain thoughts, and are trained to actively challenge their compulsive (compulsive/repetitive) behaviors and the avoidance behaviors they used to deal with those thoughts. Another method that has been developed by Cognitive Behavioral Therapy that has proven to be extremely effective is Cognitive Restructuring. As a result of using this method, clients diagnosed with pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder are taught to challenge the validity of their unwanted thoughts that cause them to suffer greatly.

In addition, a variant of EPR has been developed that has demonstrated its high efficacy in the treatment of OCD in its pure form. This method, sometimes called the "imagination" method, involves the use of short stories that are based on the patient's obsessions.![]() These stories, for a person who has pure OCD, are recorded on audio and used as an EPR tool, thereby enabling the client to experience the impact of situations that he could not experience using traditional EPR methods (for example: obsessive thoughts about killing one of the spouses or corrupting the child). By combining this method with standard EPR methods for the aforementioned obsessions, as well as other cognitive-behavioral techniques, this type of "imagination" is able to significantly reduce the frequency and magnitude of these obsessive thoughts, as well as reduce the individual's sensitivity to thoughts and images that experiencing a person with a diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder in its purest form.

These stories, for a person who has pure OCD, are recorded on audio and used as an EPR tool, thereby enabling the client to experience the impact of situations that he could not experience using traditional EPR methods (for example: obsessive thoughts about killing one of the spouses or corrupting the child). By combining this method with standard EPR methods for the aforementioned obsessions, as well as other cognitive-behavioral techniques, this type of "imagination" is able to significantly reduce the frequency and magnitude of these obsessive thoughts, as well as reduce the individual's sensitivity to thoughts and images that experiencing a person with a diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder in its purest form.

One of the most effective developments in cognitive behavioral therapy for treating people diagnosed with pure OCD is Mindfulness Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. The main goal of mindfulness-based CBT is to learn to stop the subjective perception of psychological experiences that bring discomfort to a person. From the point of view of mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy, much of the psychological stress we experience is nothing more than the result of our attempts to control and eliminate discomfort from unwanted intrusive thoughts, feelings, sensations. To put it another way, the discomfort we experience is not the problem—the problem is our attempts to control and eliminate that discomfort. For a person who suffers from pure OCD, the ultimate goal of mindfulness-based CBT is to develop the ability to more freely experience their unwanted thoughts, feelings, sensations without responding to them with avoidant behavior, seeking reassurance from other people, and/or mental (mental) rituals. . To learn more about how people diagnosed with pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder are treated with mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy, click here.

From the point of view of mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy, much of the psychological stress we experience is nothing more than the result of our attempts to control and eliminate discomfort from unwanted intrusive thoughts, feelings, sensations. To put it another way, the discomfort we experience is not the problem—the problem is our attempts to control and eliminate that discomfort. For a person who suffers from pure OCD, the ultimate goal of mindfulness-based CBT is to develop the ability to more freely experience their unwanted thoughts, feelings, sensations without responding to them with avoidant behavior, seeking reassurance from other people, and/or mental (mental) rituals. . To learn more about how people diagnosed with pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder are treated with mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy, click here.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder / OCD in its purest form - treatment using the method Hypnosuggestive Psychotherapy (hypnosis and suggestion)

In addition, the treatment of OCD in its purest form is carried out using hypnosuggestive psychotherapy. Hypno-suggestive psychotherapy is a highly effective method of treatment that includes hypnosis and suggestion. Hypnosis, or the process of hypnotization, is the immersion of a person in a temporary state of consciousness, which is characterized by a narrowing of the volume of consciousness and a sharp focus on the suggestion received. Thanks to this, hypnosis (hypnosuggestive psychotherapy) is able to introduce new, more adaptive attitudes, both at the level of consciousness and at the unconscious level. We also train a person diagnosed with pure Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in self-hypnosis skills, which allow him to consolidate and strengthen the results achieved during the work. Hypnosis, in the end, replacing unwanted behaviors, reducing discomfort from unwanted obsessions, allows you to more calmly and easily stay in situations where unwanted thoughts, feelings, sensations previously arose. Ultimately, through suggestion, hypnosis allows a person to completely get rid of his obsessive thoughts.

Hypno-suggestive psychotherapy is a highly effective method of treatment that includes hypnosis and suggestion. Hypnosis, or the process of hypnotization, is the immersion of a person in a temporary state of consciousness, which is characterized by a narrowing of the volume of consciousness and a sharp focus on the suggestion received. Thanks to this, hypnosis (hypnosuggestive psychotherapy) is able to introduce new, more adaptive attitudes, both at the level of consciousness and at the unconscious level. We also train a person diagnosed with pure Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in self-hypnosis skills, which allow him to consolidate and strengthen the results achieved during the work. Hypnosis, in the end, replacing unwanted behaviors, reducing discomfort from unwanted obsessions, allows you to more calmly and easily stay in situations where unwanted thoughts, feelings, sensations previously arose. Ultimately, through suggestion, hypnosis allows a person to completely get rid of his obsessive thoughts. To learn more about how people with pure OCD are treated using hypnosis, click here.

To learn more about how people with pure OCD are treated using hypnosis, click here.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder / Pure OCD: Individual Treatment / Psychotherapy

Kyiv OCD Center provides individual treatment (psychotherapy) for adults and adolescents who suffer from pure OCD. The main methods of treatment are: cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, hypno-suggestive psychotherapy (hypnosis and suggestion). If you want to learn more about how individual treatment is carried out for people with a diagnosis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in its purest form, you can call us by phone or write in any way convenient for you.

Pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder/OCD: Group Treatment/Psychotherapy

In addition to individual treatment for people diagnosed with Pure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, OCD Kyiv Center conducts weekly treatment groups for pure OCD and related disorders . Studies show that group treatment of people with OCD in its purest form, using cognitive-behavioral and hypnosuggestive psychotherapy, is highly effective. In the Kyiv Center for OCD, all groups for the treatment of people who have been diagnosed with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in its purest form are carried out by our specialists, the programs that they use are the same as in individual treatment. It should be noted that before you can get into the group, you need to undergo an individual psychodiagnostic consultation, only adults over 18 years of age, with diagnoses of OCD, pure obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as concomitant anxiety disorders, can participate in group treatment . For more information on group therapy / support groups, please click here.

In the Kyiv Center for OCD, all groups for the treatment of people who have been diagnosed with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in its purest form are carried out by our specialists, the programs that they use are the same as in individual treatment. It should be noted that before you can get into the group, you need to undergo an individual psychodiagnostic consultation, only adults over 18 years of age, with diagnoses of OCD, pure obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as concomitant anxiety disorders, can participate in group treatment . For more information on group therapy / support groups, please click here.

Article

MOD MOTH VITIAY Andreevich

Psychologist - Psychotherapist

hypnologist - Hypnotherapist

Last editing: 03/14/2018

our advantages

since 2006

Customers 9000 9000 more

more 6000 9000. more than 96%

Sign up

On our website you can pay by Visa or MasterCard from anywhere in the world, Payment by installments from Privat Bank is available

OCD test

Table of contents↓[show]

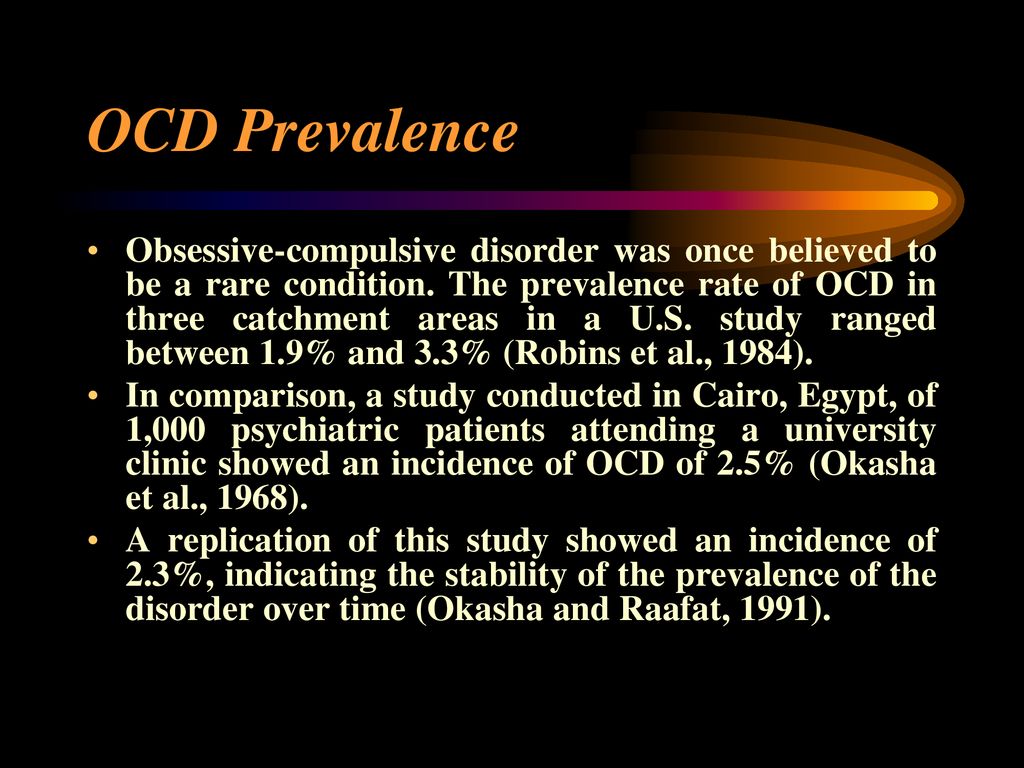

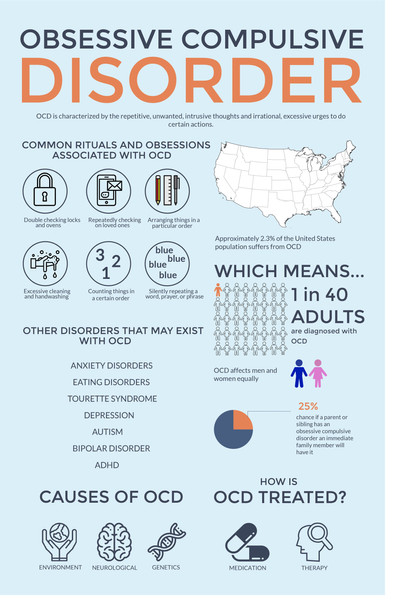

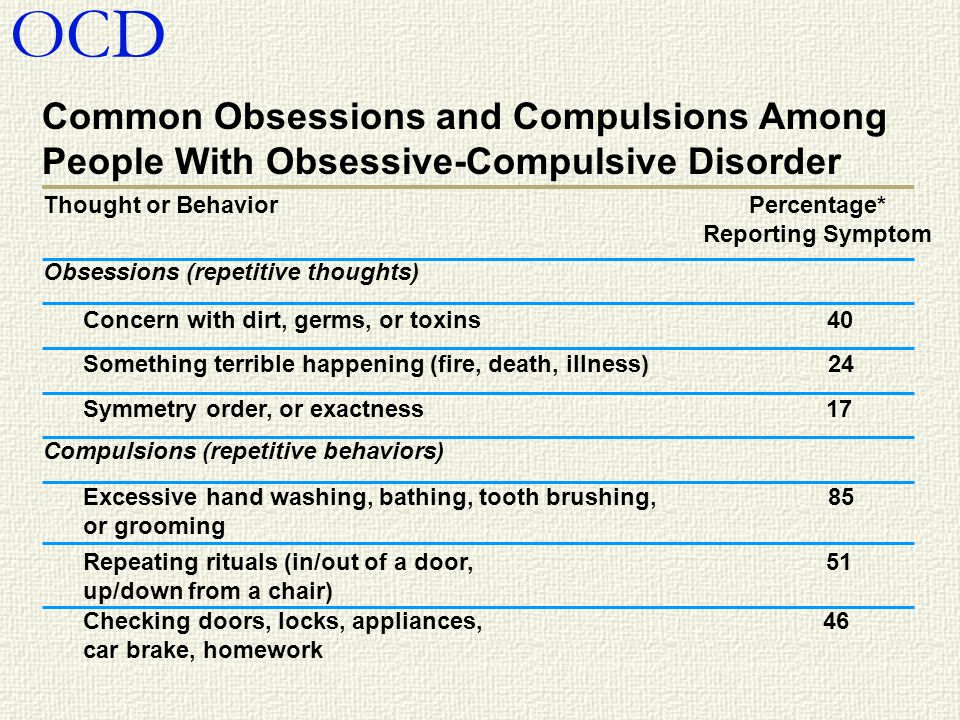

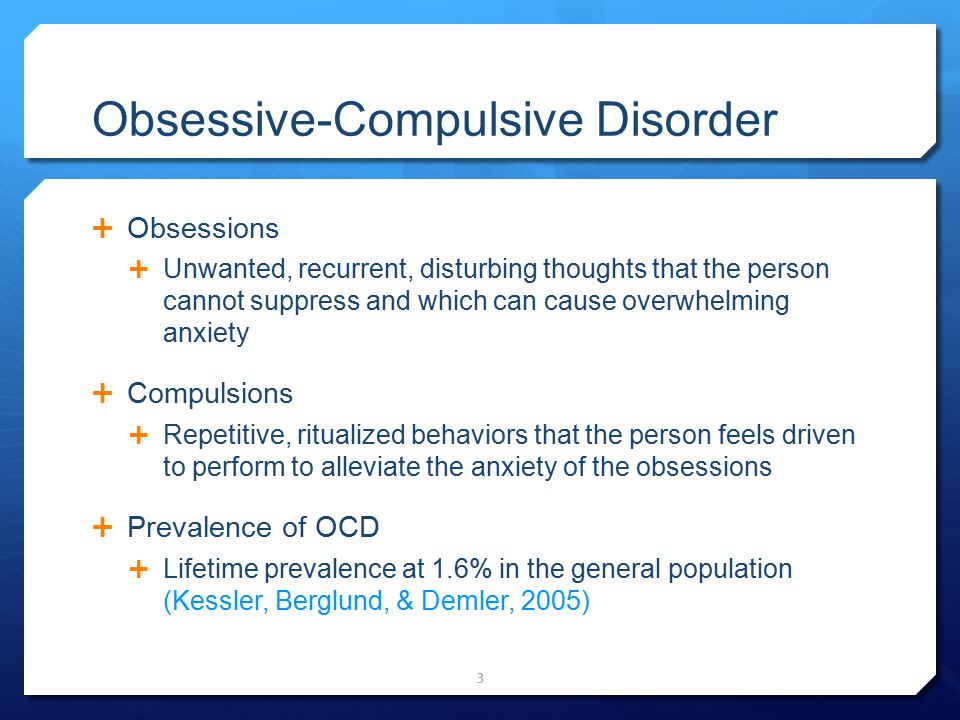

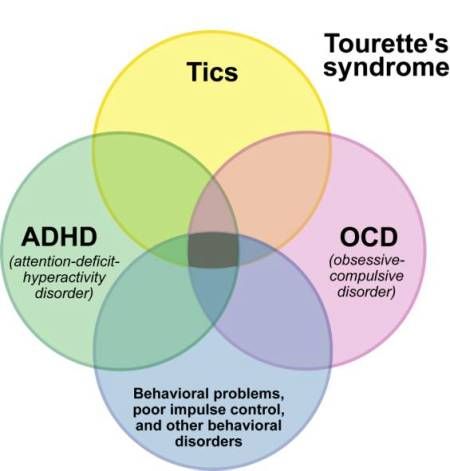

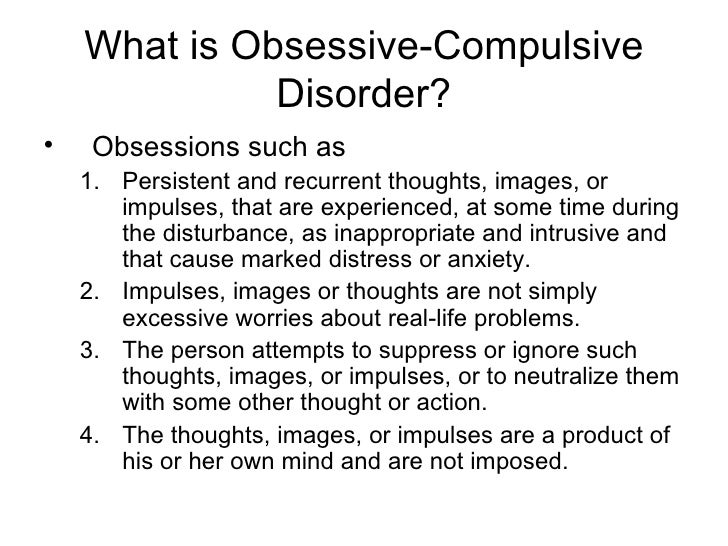

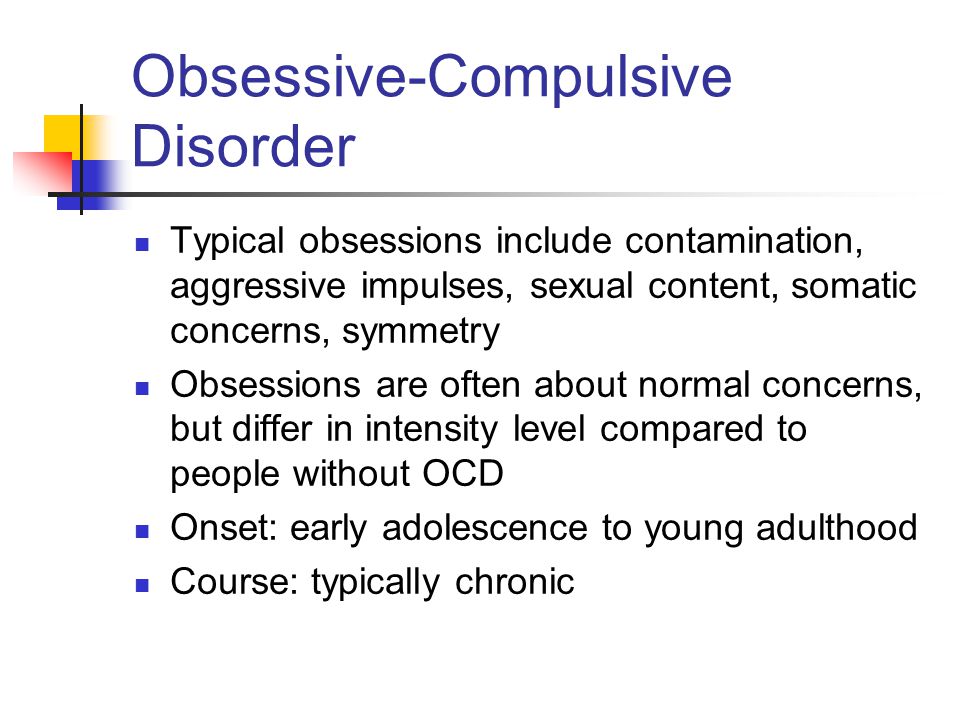

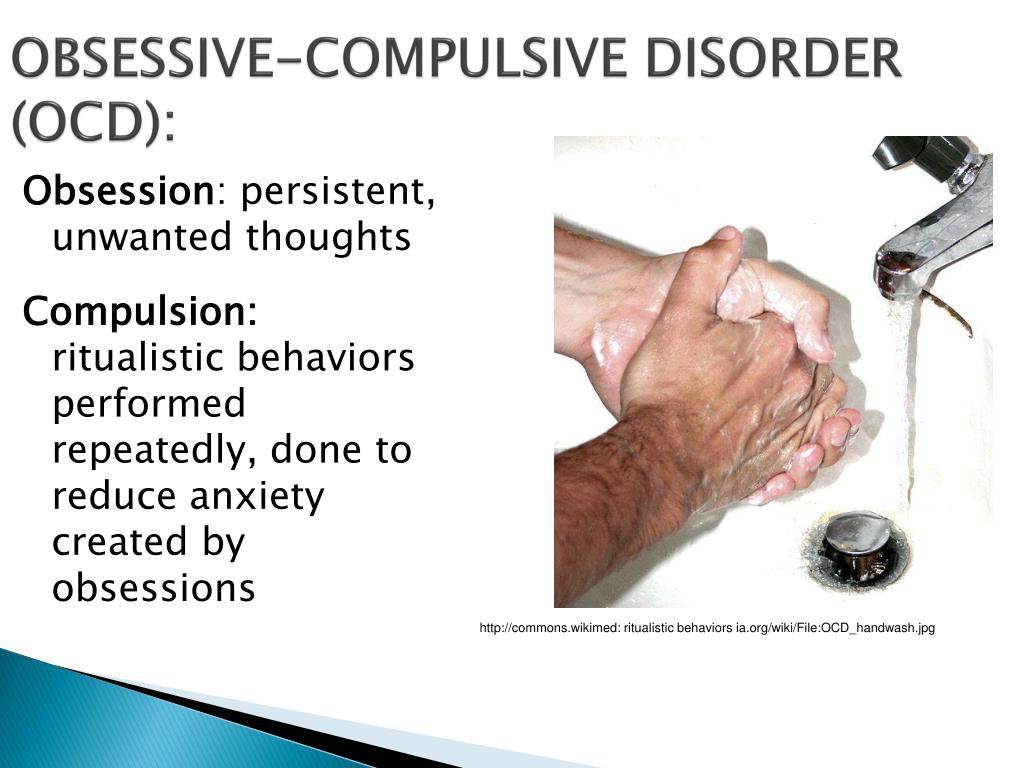

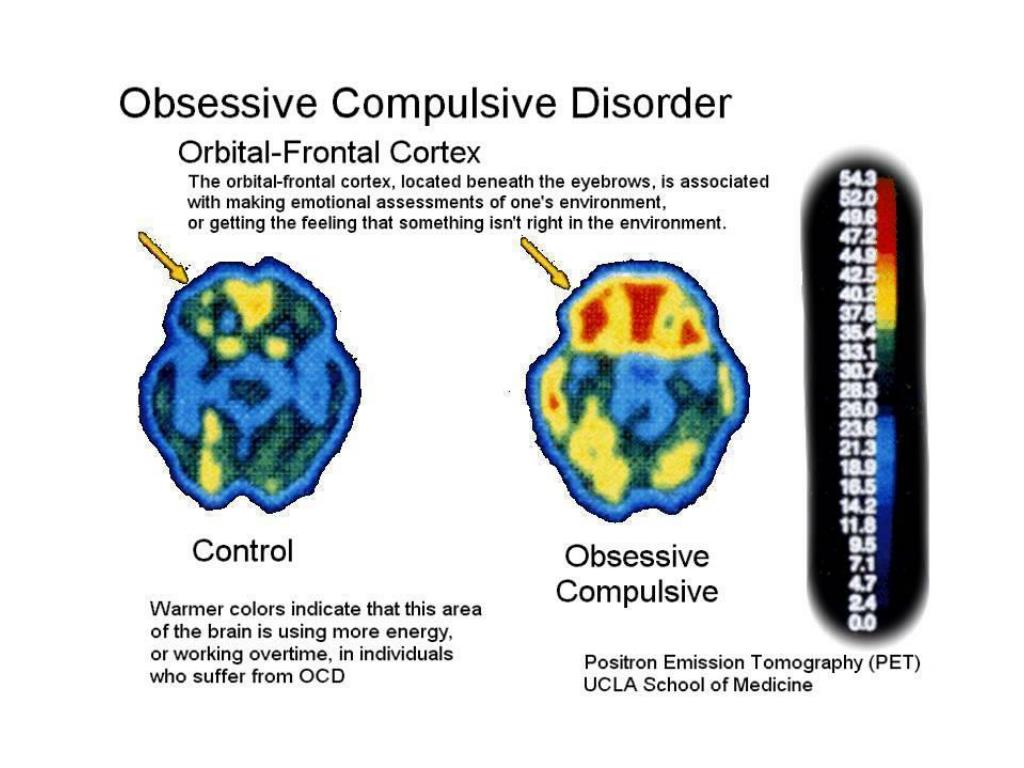

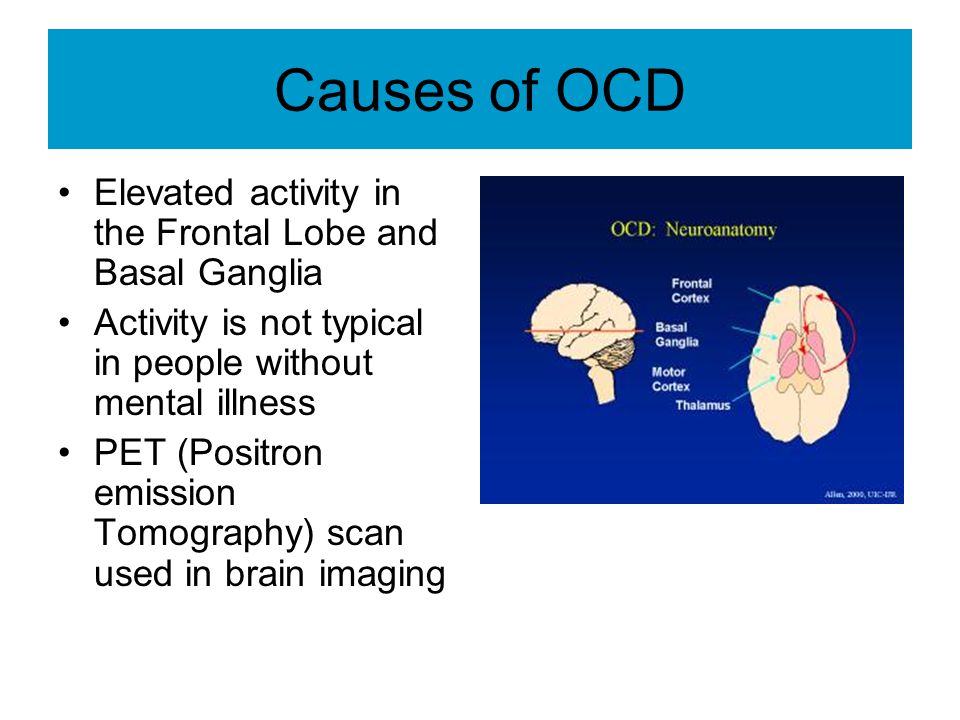

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic and disabling neuropsychiatric condition with a prevalence of about 2% in Russia. The disease is characterized by the presence of obsessions (repetitive and persistent thoughts perceived as intrusive or inappropriate and causing marked anxiety or stress) or compulsions (repetitive or mental actions that a person experiences in an effort to perform, usually to reduce the resulting anxiety) obsession. The Yusupov Hospital employs highly qualified doctors who have specialized in psychiatry, have a scientific degree and extensive experience in the diagnosis and treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. If you have any questions, you can sign up for a consultation online, on the website of the Yusupov Hospital, Moscow, and discuss issues of diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation.

The disease is characterized by the presence of obsessions (repetitive and persistent thoughts perceived as intrusive or inappropriate and causing marked anxiety or stress) or compulsions (repetitive or mental actions that a person experiences in an effort to perform, usually to reduce the resulting anxiety) obsession. The Yusupov Hospital employs highly qualified doctors who have specialized in psychiatry, have a scientific degree and extensive experience in the diagnosis and treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. If you have any questions, you can sign up for a consultation online, on the website of the Yusupov Hospital, Moscow, and discuss issues of diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation.

Diagnosis of OCD

Accurate evaluation of OCD is critical due to its underdiagnosis, the difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis, and the need for careful and specific treatment planning and evaluation. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Adults: A Test for OCD. A person suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder may be obsessed with germs or their safety, and may only find relief from their associated anxiety by performing rituals such as washing hands repeatedly or ritually locking and unlocking doors. If you suspect that you may have obsessive-compulsive disorder, take an obsessive-compulsive disorder test to determine if your symptoms warrant a visit to a qualified healthcare professional. An accurate diagnosis can only be made by clinical evaluation.

If you suspect that you may have obsessive-compulsive disorder, take an obsessive-compulsive disorder test to determine if your symptoms warrant a visit to a qualified healthcare professional. An accurate diagnosis can only be made by clinical evaluation.

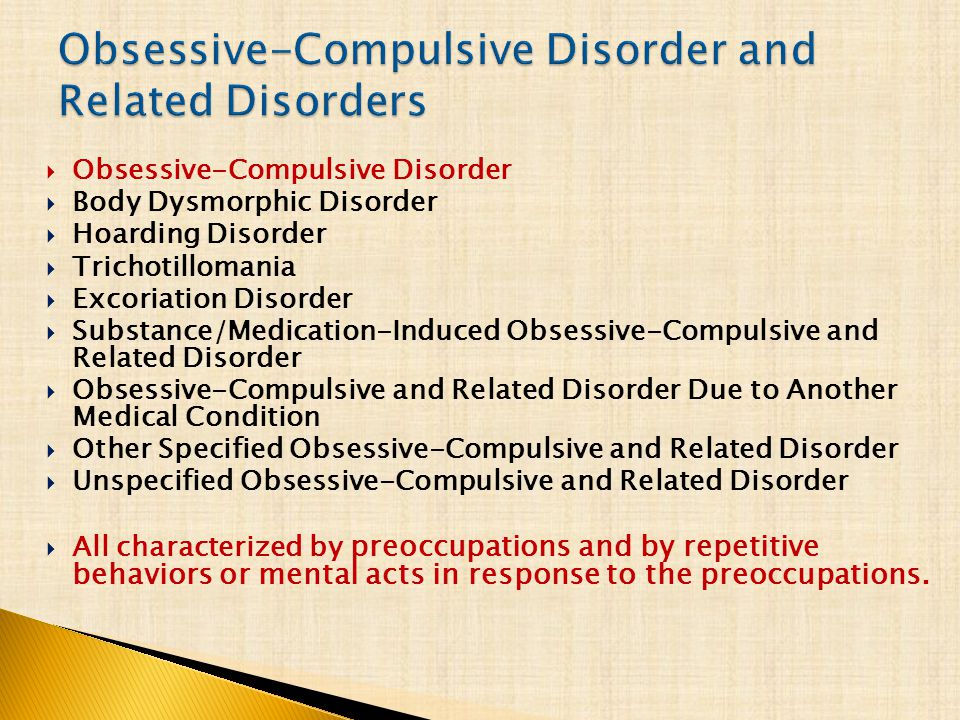

Adult obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by three signs or symptoms:

- Obsessions, which are unwanted thoughts, images, or urges that cause distress;

- Compulsions, which are repetitive actions or thoughts that a person uses to neutralize or counteract negative feelings or thoughts;

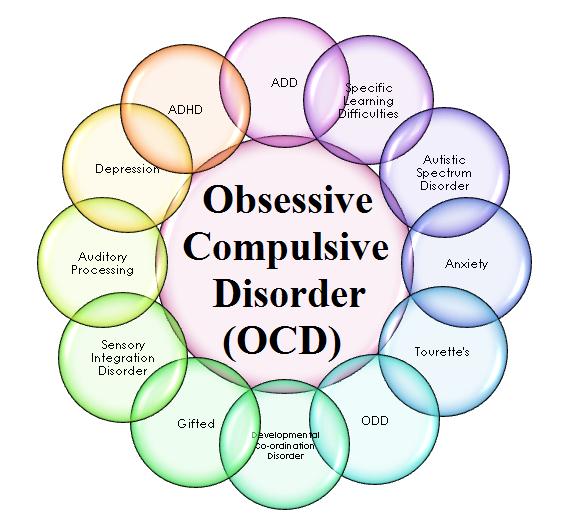

- Anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder can be diagnosed if someone has obsessions, compulsions, or both. Because obsessions and compulsions can take any form, and OCD varies greatly in severity, diagnosis can be difficult and usually requires a specialist who can correctly diagnose the conditions.

If the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder are left untreated, they may worsen, which may lead to unwanted consequences. The good news is that after an accurate diagnosis, most patients undergoing treatment report an improvement in their obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms.

The good news is that after an accurate diagnosis, most patients undergoing treatment report an improvement in their obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms.

If you suspect you have obsessive-compulsive disorder, the Yale Brown test can help you confirm or refute your suspicions.

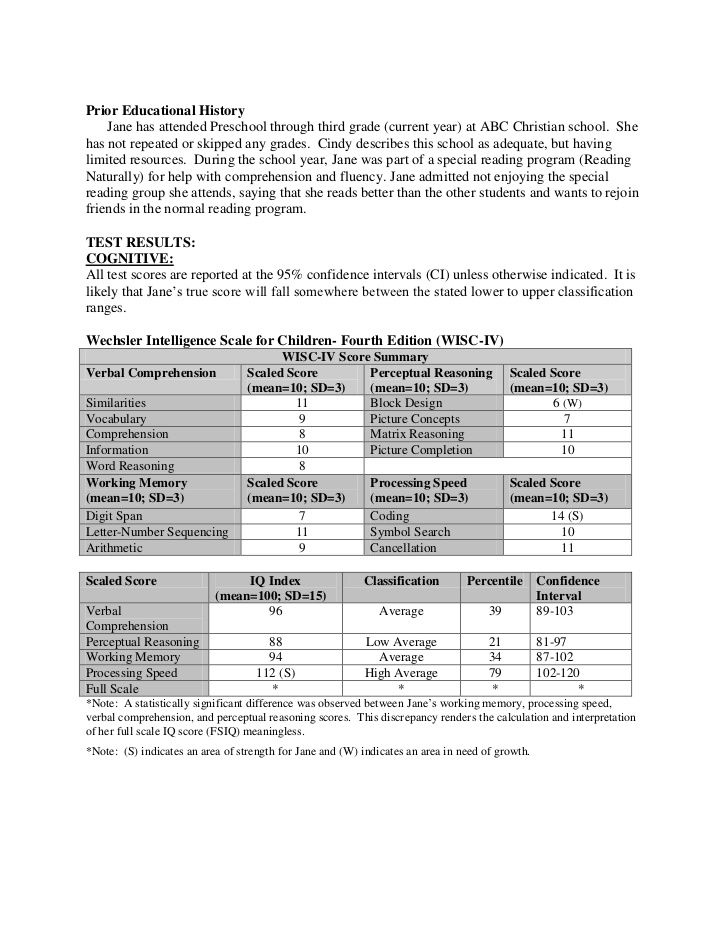

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: The Yale Brown Test

The Yale Brown Test is the gold standard for measuring the severity of OCD symptoms. This test has excellent psychometric properties for assessing the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms reflecting obsessive-compulsive changes, and the test has good sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale is a clinician-driven tool developed in 1989 to assess the presence and severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. It is divided into a symptom checklist and a severity scale. The symptom checklist includes 54 dichotomous items assessing the current or past presence of certain obsessions and urges. The severity scale consists of 10 items that quantify the impact of obsessions and compulsions as identified by the symptom checklist.

The severity scale consists of 10 items that quantify the impact of obsessions and compulsions as identified by the symptom checklist.

However, several problems were identified for this scale, including a poor conceptual fit of the obsession resistance element, possibly contributing to factor structure inconsistency.

To address these issues, a revised version of the Yale Brown scale was published in 2000, with some differences from the original scale. In particular, obsessions and compulsions checklists are not formally subdivided into different symptom groups, some items on the symptom checklist have been rewritten and expanded, and a new checklist has been created. In addition, on the severity scale, the element grading "obsessiveness resistance" was replaced by the "interval without obsessions" element. Finally, the definitions of possession and coercion have been rephrased, and some supporting elements have been removed from the text.

Yale Brown test (OCD test)

The first five questions are about obsessive thoughts, the last five questions are about compulsive behavior.

Questions:

1) How much of your time is occupied by obsessive thoughts in a 24 hour period?

- do not waste time on intrusive thoughts,

- less than 1 hour per day,

- 1-3 hours per day,

- 3-8 hours per day,

- more than 8 hours per day.

2) How much do your obsessive thoughts interfere with your social, work or other areas?

- do not interfere,

- slightly interfere, but do not interfere with work and life,

- interfere, but are controllable,

- significantly interfere,

- greatly interfere, lead to loss of performance.

3) How disturbing are your obsessive thoughts?

- not causing;

- mild, not too anxious;

- moderate, anxious, manageable;

4) How much effort do you make to resist intrusive thoughts?

- sometimes you try to resist, or you don't even need to resist,

- you try to resist most of the time,

- you make some effort to resist,

- you are reluctant to give in to all obsessive thoughts,

- you always willingly give in to obsessive thoughts.

5) How much do you control your obsessive thoughts?

- completely in control,

- strong control, able to stop or distract obsessions with some effort and concentration,

- moderate control, sometimes succeed in stopping or distracting obsessions,

- slight control, rarely successful in stopping or deflecting obsessions ideas,

- no control, in rare cases able to change obsessive thinking.

6) How much time do you spend doing compulsive behavior?

- don't waste time,

- less than 1 hour a day,

- 1-3 hours a day,

- 3-8 hours a day,

- more than 8 hours a day.

7) To what extent does your compulsive behavior interfere with your life?

- no interference,

- slight interference, but no impairment of function,

- certain controllable interference,

- significant interference,

- severe incapacitating effect.

8) How much would you worry if you were prevented from being obsessive?

- no anxiety,

- slightly anxious,

- some controllable anxiety,

- severe anxiety.

- very strong anxiety, incapacitating restlessness.

9) How much effort do you spend to resist coercion?

- sometimes you try to resist, sometimes without resistance,

- try to resist most of the time,

- need some effort to resist,

- reluctantly succumb to coercion,

- completely and willingly succumb to resistance.

10) How much do you control compulsions?

- full control,

- great control, usually able to stop or distract compulsive behavior with some effort,

- moderate control, can sometimes stop or distract compulsive behavior,

- little control, rarely successful in stopping the obsessive state,

- no control, rarely able to change compulsive behavior even for a moment.

Each answer has its own score:

- 1 answer - 0 points;

- 2nd option - 1 point;

- 3rd option - 2 points;

- 4th answer - 3 points,

- 5th answer - 4 points.

Scoring: if you have both obsession and compulsion and your total score is:

- 8-15 - mild OCD;

- 16-23 - moderate OCD;

- 24-31 - severe OCD,

- 32-40 - extreme OCD.

This test is not completely accurate. You should always consult a specialist about your health.

If you have been tested for OCD and have questions, you can contact the Yusupov Hospital. For each patient, the psychiatrist selects an individual approach, after asking complaints and excluding all diseases that can mimic obsessive-compulsive disorder, he makes a diagnosis, if necessary, it is possible to consult an adjacent specialist. And only after that he prescribes a treatment developed for each patient individually in view of his characteristics.