Is ocd a type of autism

OCD and autism: How can you tell the difference?

by Mendability

It is normal to wonder

When your child with autism suddenly demonstrates a new repetitive behavior, it is normal to ask yourself: Is this OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder)? Parents are justifiably concerned if a new stim appears, or if their child seems to develop a new compulsive habit, such as leaving the house, going back in, and then walking out the door again every time you want to go out.

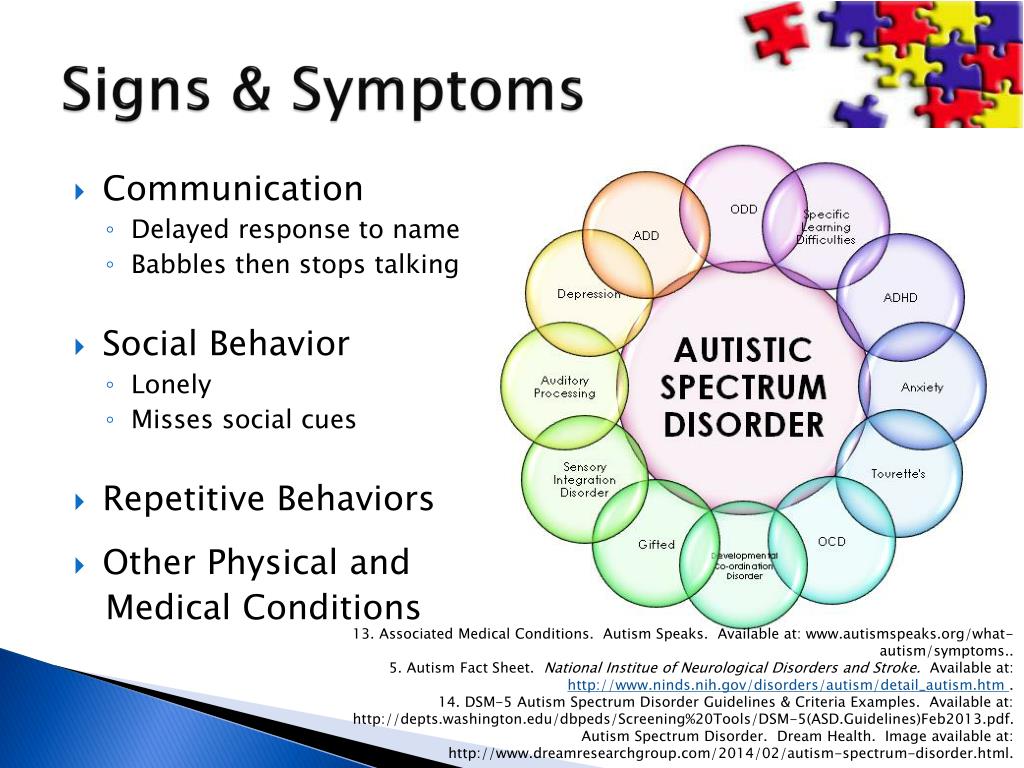

Autistic symptoms and OCD can look similar

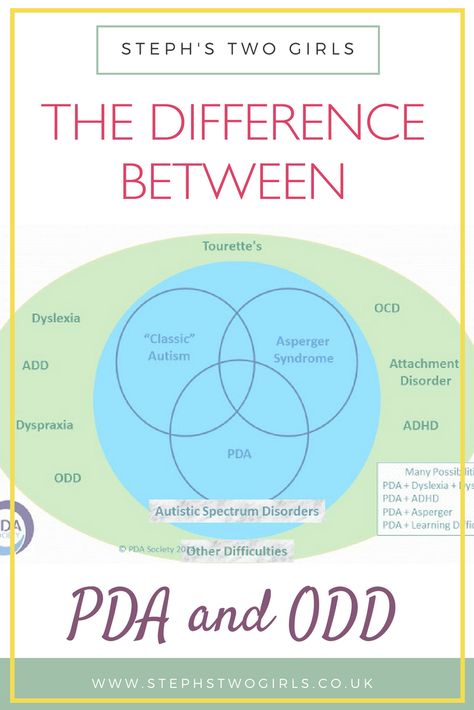

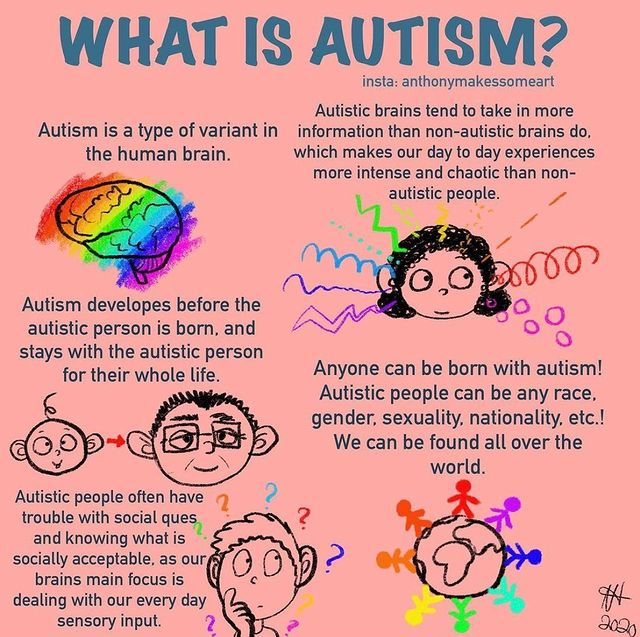

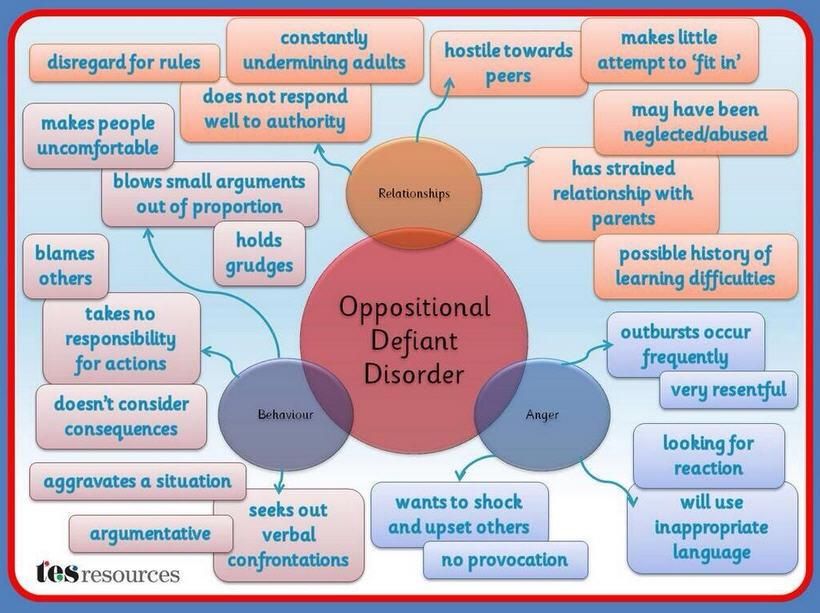

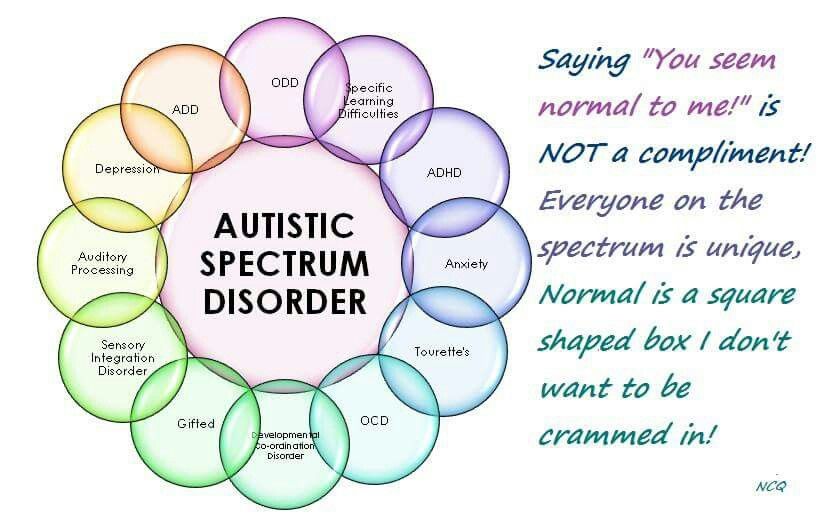

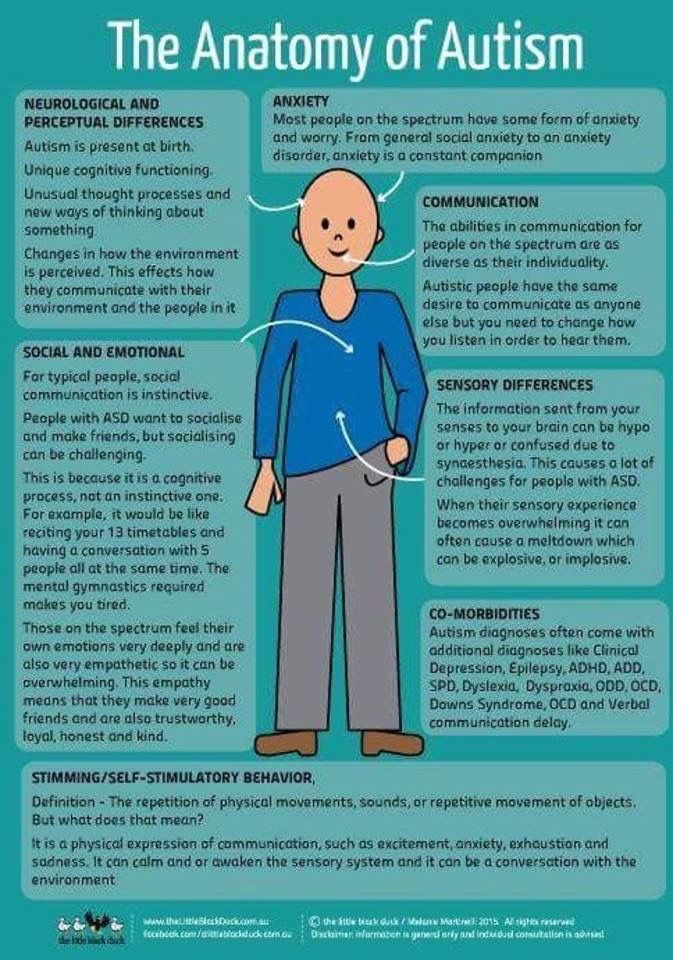

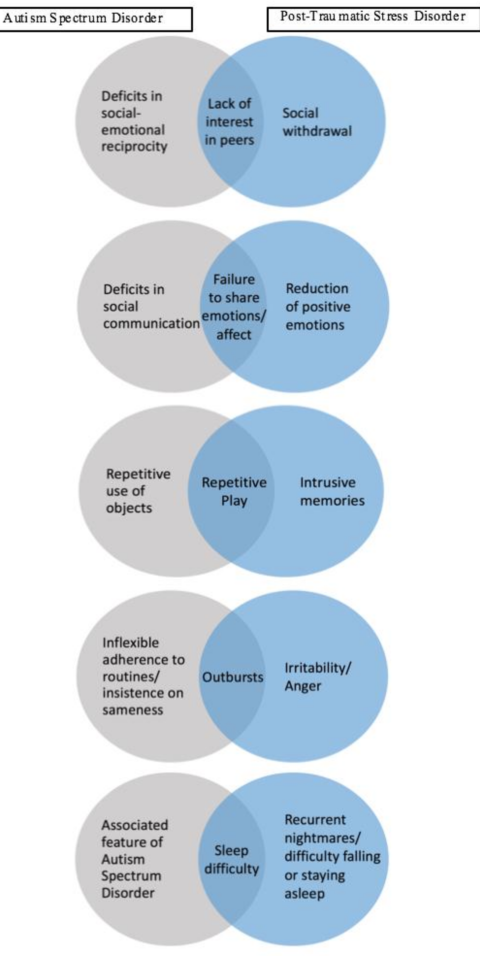

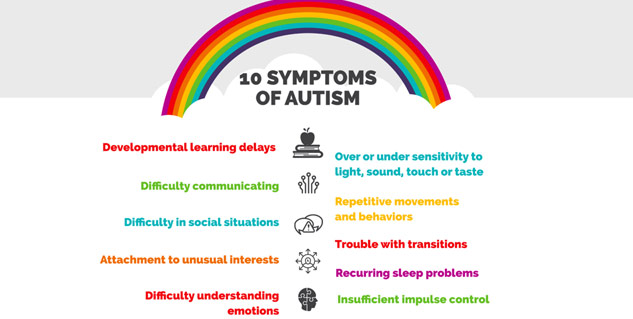

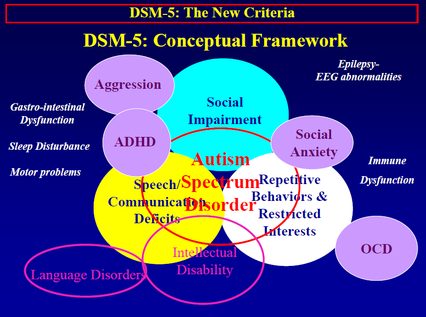

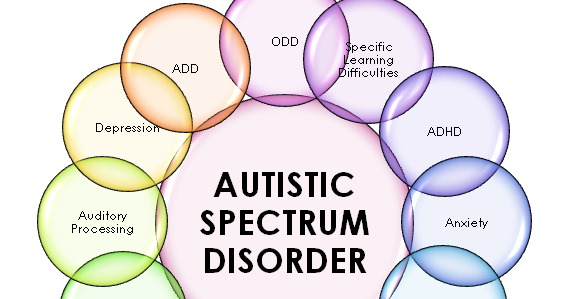

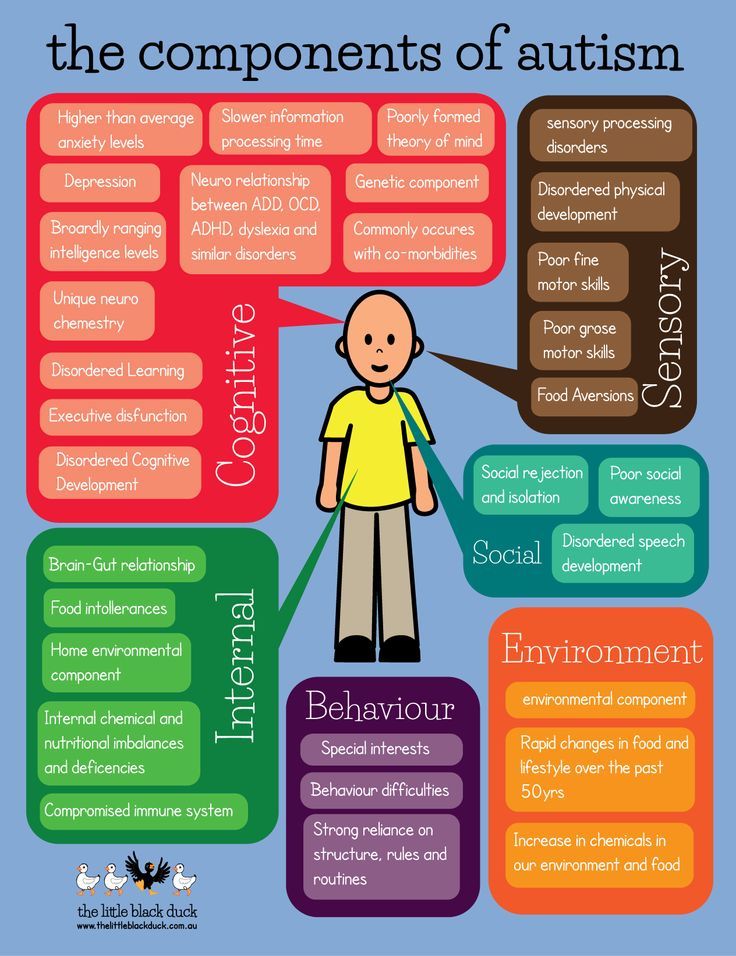

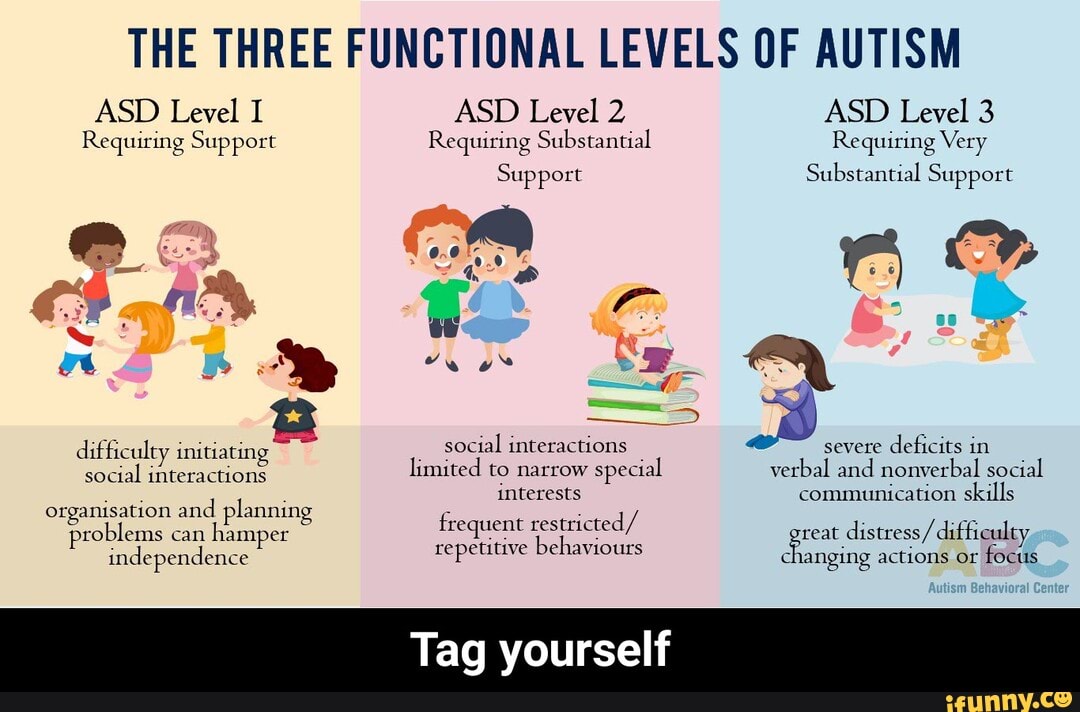

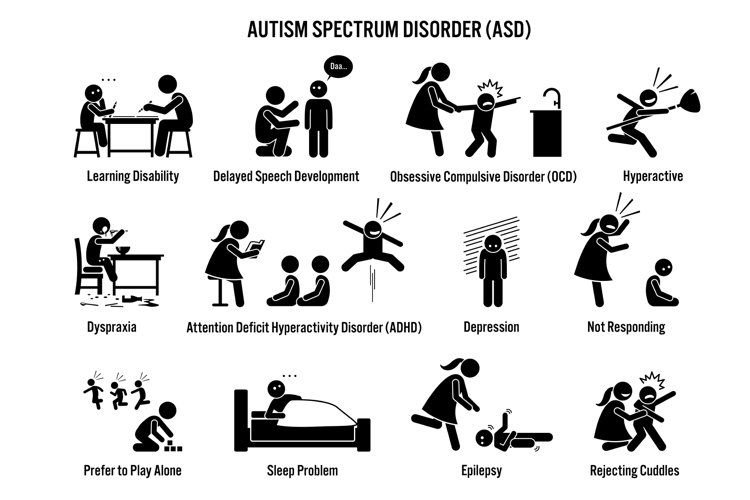

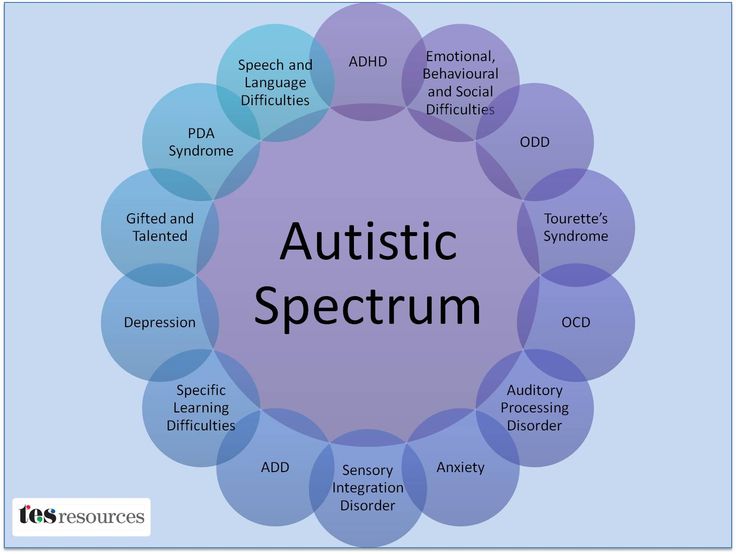

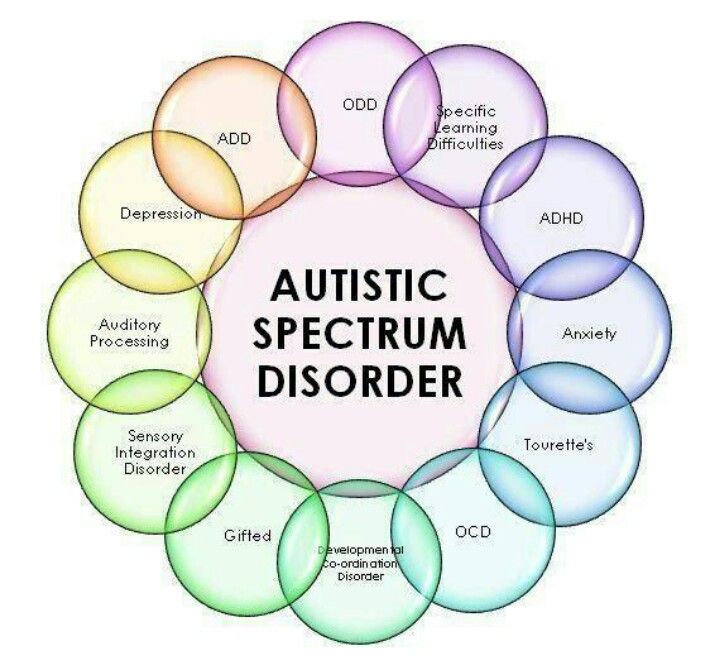

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and OCD are two different conditions, however, it is true that some symptoms of autism overlap with those of other disorders, such as OCD, and can look similar (Højgaard et al. 2016). For example, people with autism and people with OCD may display repetitive behaviors, obsessive behaviors and severe anxiety. Both children with OCD and children with autism can become very rigid and resistant to change. A key difference between OCD and autism is the purpose or motivation for the behavior.

Repetitive behaviors as a venting mechanism

For example, a child with autism may demonstrate that he is feeling anxious or excited by lining up items such as small cars, by playing with an object at the side of his eye, or by flapping his hands or arms while hopping in place or running in circles. Verbal adults with autism have enlightened us as to the meaning of such repetitive behaviors. They explain that these actions can soothe their anxiety and give them a feeling of control in an uncontrollable situation.

When a parent sees their child with autism lining up toy cars, they may think this looks like an OCD behavior. If someone breaks the line, the child may go straight back to building it again, in an almost robotic manner. However, the child may also suddenly drop the behavior and move to another activity without any specific reason, which is not typical of someone with OCD.

OCD symptoms are different

While most children with autism have repetitive movements or vocal tics that show us when they are feeling anxious or excited, the source of the obsessive habits of someone with OCD is different. When someone with OCD feels driven to fill their life with repetitive patterns this is part of a mental process. Their compulsive behaviors have complicated motives which are not reasonable and which, in themselves, are part of the diagnosis.

When someone with OCD feels driven to fill their life with repetitive patterns this is part of a mental process. Their compulsive behaviors have complicated motives which are not reasonable and which, in themselves, are part of the diagnosis.

A child with OCD will explain why she needs something to be done exactly as she demands and will not be able to move from this rigid behavior. For example, she may be unable to eat her yogurt if there is a small piece of metal foil stuck to the rim of the container. No amount of coaxing or patient reasoning from the parent will make any difference or be able to reduce the child’s anxiety.

Stimming vs. OCD: Different motivations

OCD children are constantly bombarded with terrifying thoughts about imminent danger which cause a state of panic leading to obsessive behaviors. Children with autism do not tend to think about their stim as a purposeful action.

Professor Temple Grandin, a knowledgeable and trustworthy expert on autism, says: “Most kids with autism do these repetitive behaviors because it feels good in some way” (Grandin, 2011). This statement is a powerful description of the difference between a person with autism who stims and the compulsive rituals of someone with OCD.

This statement is a powerful description of the difference between a person with autism who stims and the compulsive rituals of someone with OCD.

Another way to observe differences

In addition to asking a child about his motivations and fears, you may be able to make the distinction between a repetitive act in OCD and a stim in autism by trying to stop it. In our experience, if you interrupt an autistic child’s repetitive routine he will not show distress and you may be able to redirect his attention with a new object or invitation, but he will probably develop a new stim. However, since the repetitive behaviors of a child with OCD are related to deep fears, if you were to try to stop their routine, they could become extremely distressed to the point of having a panic attack.

Monitor the behavior and consult a doctor

In conclusion, when a person with autism shows a new stimming behavior, this can indicate an increase in their anxiety level, or it may be a developmental stage, or an indicator of OCD. When someone with OCD displays repetitive behaviors, these patterns are the result of sophisticated thinking, they have a crucial purpose for that person and are never isolated from their purpose. Monitoring the new repetitive behavior by taking notes and possibly filming it, will be helpful when you talk with the person’s physician. Your physician will be the best person to advise you about whether this new situation requires further attention.

When someone with OCD displays repetitive behaviors, these patterns are the result of sophisticated thinking, they have a crucial purpose for that person and are never isolated from their purpose. Monitoring the new repetitive behavior by taking notes and possibly filming it, will be helpful when you talk with the person’s physician. Your physician will be the best person to advise you about whether this new situation requires further attention.

We also recommend Mendability for children with autism and OCD. Mendability delivers Sensory Enrichment Therapy (SET) online. The benefits of SET for children with autism are clinically proven.

References

- Grandin, Temple PhD. “Why Do Kids with Autism Stim?” Autism Asperger’s Digest, November/December 2011.

- Højgaard, Davíð R. M. A., Gudmundur Skarphedinsson, Judith Becker Nissen, Katja A. Hybel, Tord Ivarsson, and Per Hove Thomsen. 2016. “Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder with Tic Symptoms: Clinical Presentation and Treatment Outcome.

” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, December. doi:10.1007/s00787-016-0936-0.

” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, December. doi:10.1007/s00787-016-0936-0.

Untangling the ties between autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder | Spectrum

Autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder frequently accompany each other; scientists are studying both to understand how they differ.

Photography by Rebecca Horne, props by Cadence Giersbach

Steve Slavin was 48 years old when a visit to a psychologist’s office sent him down an unexpected path. At the time, he was a father of two with a career in the music industry, composing scores for advertisements and chart toppers. But he was having a difficult year. He had fewer clients than usual, his mother had been diagnosed with cancer, and he was battling anxiety and depression, leading him to shutter his recording studio.

Slavin’s anxiety — which often manifested as negative thoughts and routines characteristic of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) — was nothing new. As a child, he had often felt compelled to swallow an even number of times before entering a room, or to swallow and count — one foot in the air — to four, six or eight before stepping on a paving stone. As an adult, he frequently became distressed in crowds, and he washed his hands over and over to avoid being contaminated by other people’s germs or personalities. His depression, too, was familiar — and had caused him to withdraw from friends and colleagues.

As an adult, he frequently became distressed in crowds, and he washed his hands over and over to avoid being contaminated by other people’s germs or personalities. His depression, too, was familiar — and had caused him to withdraw from friends and colleagues.

This time, as Slavin’s depression and anxiety worsened, his doctor referred him to a psychologist. “I had had an appointment booked for weeks and weeks and months,” he recalls. But about 10 minutes into his first session, the psychologist suddenly changed course: Instead of continuing to ask him about his childhood or existing mental-health issues, she wanted to know whether anyone had ever talked to him about autism.

By coincidence, a relative had mentioned autism to Slavin two days prior, wondering if it might explain why he dislikes social situations. Slavin knew little about the condition but had conceded it was possible. By the time his therapy session ended, his psychologist was almost certain: “She said to me that I’ve either got high-functioning autism or some kind of brain damage,” Slavin recalls with a chuckle. Only a few years earlier, a doctor had finally diagnosed him with OCD. His new psychologist diagnosed him with autism as well.

Only a few years earlier, a doctor had finally diagnosed him with OCD. His new psychologist diagnosed him with autism as well.

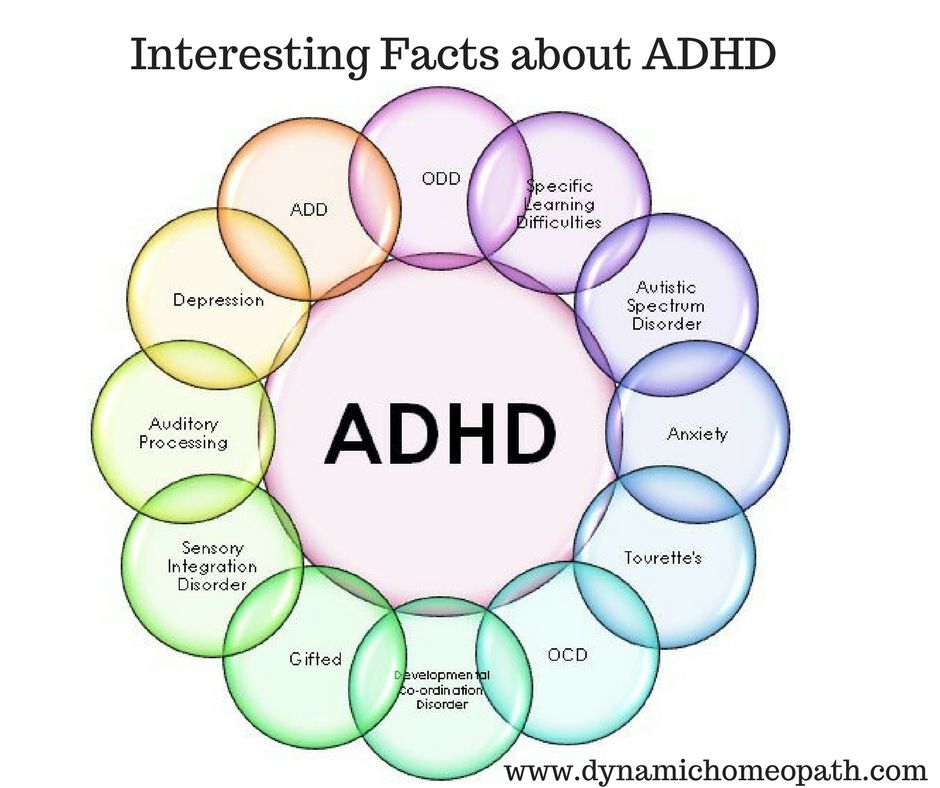

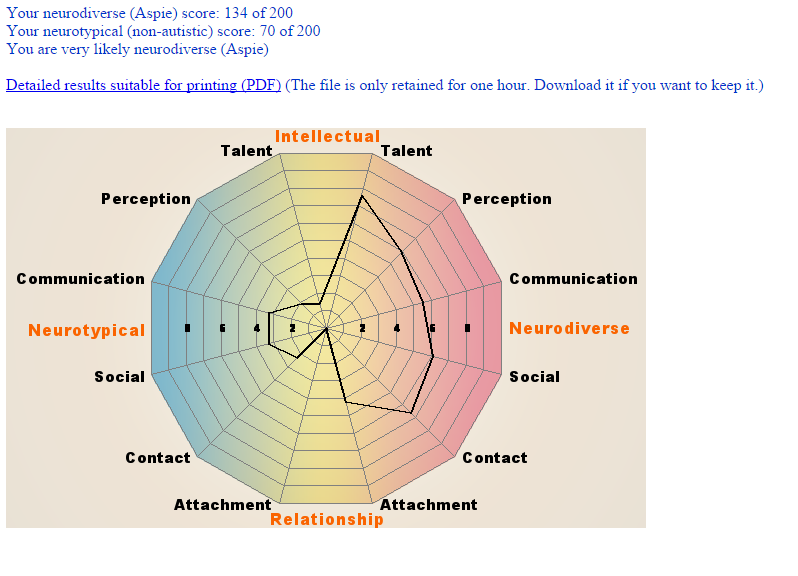

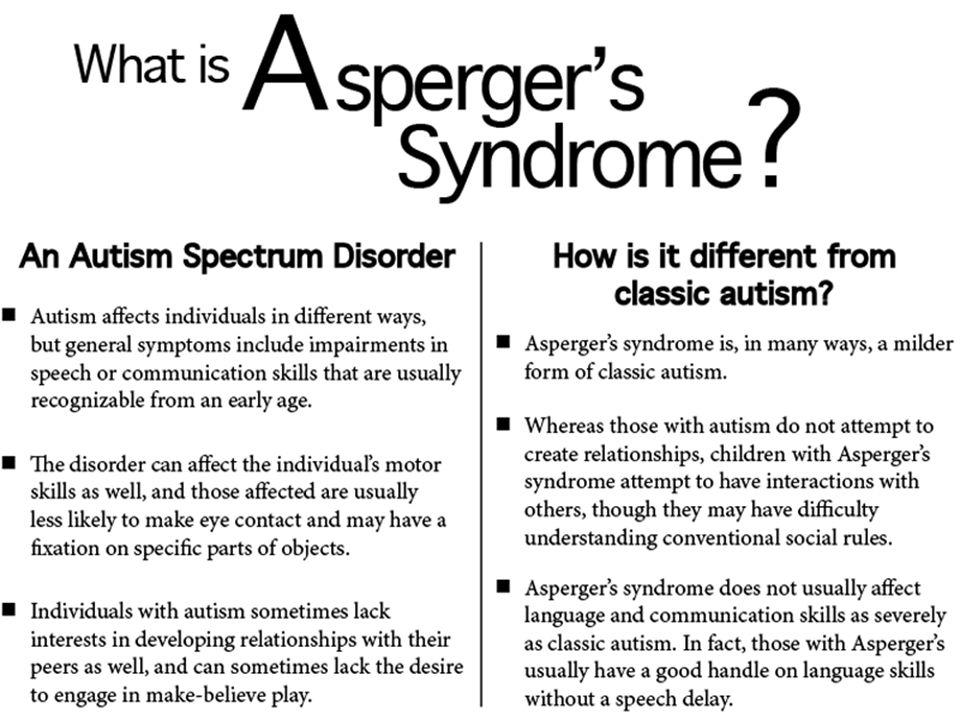

At first glance, autism and OCD appear to have little in common. Yet clinicians and researchers have found an overlap between the two. Studies indicate that up to 84 percent of autistic people have some form of anxiety; as much as 17 percent may specifically have OCD. And an even larger proportion of people with OCD may also have undiagnosed autism, according to one 2017 study.

Part of that overlap may reflect misdiagnoses: OCD rituals can resemble the repetitive behaviors common in autism, and vice versa. But it’s increasingly evident that many people, like Slavin, have both conditions. People with autism are twice as likely as those without to be diagnosed with OCD later in life, according to a 2015 study that tracked the health records of nearly 3.4 million people in Denmark over 18 years. Similarly, people with OCD are four times as likely as typical individuals to later be diagnosed with autism, according to the same study.

In the past decade, researchers have begun to study these two conditions together to work out how they interact — and how they differ. Those distinctions could be important not only for making correct diagnoses but also for choosing effective treatments. People who have both OCD and autism appear to have unique experiences, distinct from those of either condition on its own. And for these people, standard interventions for OCD, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), may provide little relief.

“It’s complicated to tease out anxiety from autism.” Roma VasaMissed diagnoses:

Obsessions and compulsions can strike anyone: It’s common to worry about having left the oven on or to rifle anxiously through a purse in search of keys. “They’re really part of the normal experience,” says Ailsa Russell, clinical psychologist at the University of Bath in the United Kingdom. Most people find ways to dismiss those unpleasant thoughts and move on. Among people with OCD, though, those worries build up over time and disrupt daily functioning.

Among people with OCD, though, those worries build up over time and disrupt daily functioning.

Some people, like Slavin, count steps or breaths to quell their terror that something bad will happen. Others describe themselves as ‘checkers,’ who investigate — again and again — that they’ve done a task properly. Still others are ‘cleaners,’ who wash constantly in response to a fear of filth and contamination. “Mostly, people with OCD realize it’s not that rational,” Russell says, but feel trapped by their worries and rituals.

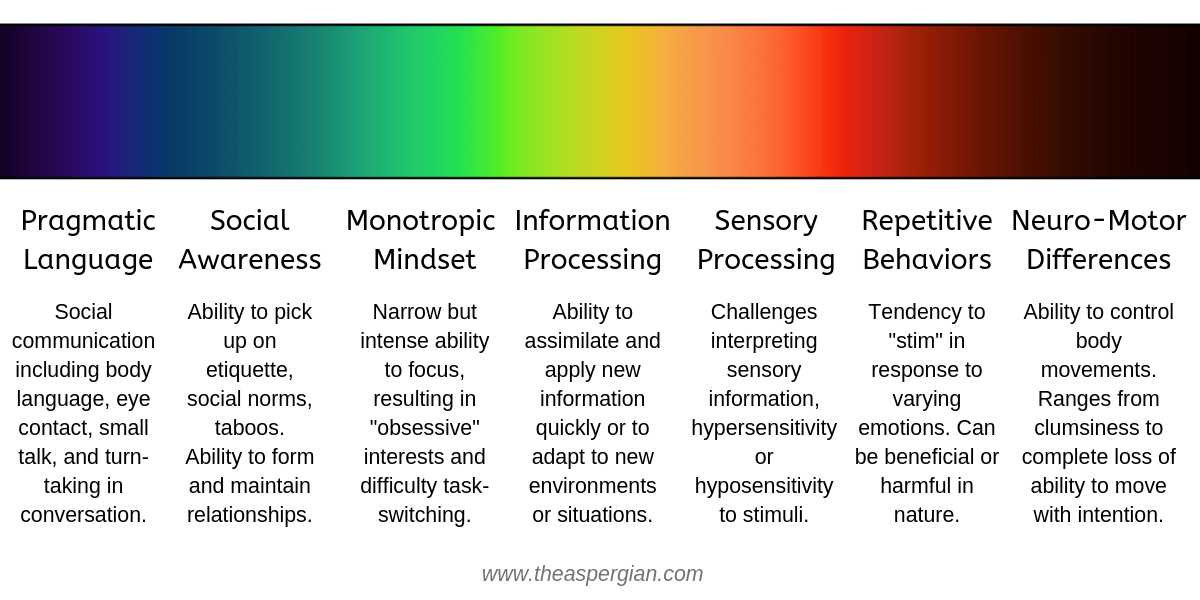

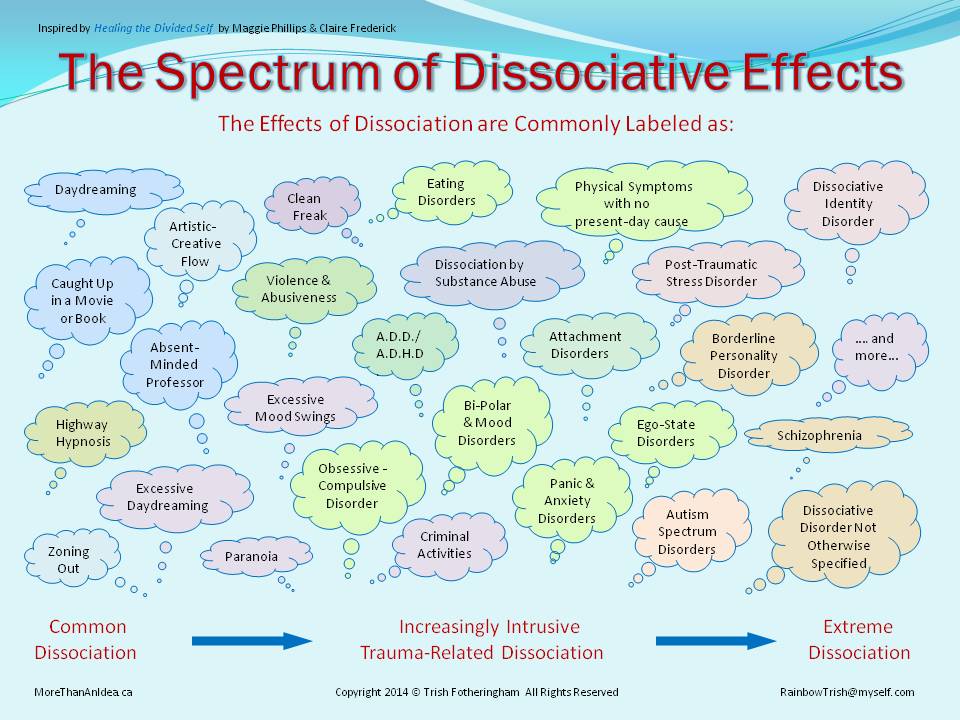

The overlap between OCD and autism is still unclear. People with either condition may have unusual responses to sensory experiences, according to a 2015 analysis. Some autistic people find that sensory overload can readily lead to distress and anxiety. Slavin, for example, dreads police sirens and the peal of doorbells, which he likens to a bomb exploding in his nervous system. Some researchers say the social problems people with autism experience may contribute to their anxiety, which is also a component of OCD. Not being able to read social cues might lead people to become isolated or be bullied, fueling anxiety, the reasoning goes. “It’s complicated to tease out anxiety from autism,” says Roma Vasa, director of psychiatric services at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

Not being able to read social cues might lead people to become isolated or be bullied, fueling anxiety, the reasoning goes. “It’s complicated to tease out anxiety from autism,” says Roma Vasa, director of psychiatric services at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

These shared traits make autism and OCD difficult to distinguish. Even to a trained clinician’s eye, OCD’s compulsions can resemble the ‘insistence on sameness’ or repetitive behaviors many autistic people show, including tapping, ordering objects and always traveling by the same route. Untangling the two requires careful work.

One crucial distinction, the 2015 analysis found, is that obsessions spark compulsions but not autism traits. Another is that people with OCD cannot swap the specific rituals they need, Vasa says: “They have a need to do things a certain way, otherwise they feel very anxious and uncomfortable.” By contrast, autistic people often have a repertoire of repetitive behaviors to choose from. “They’re just looking for anything that’s soothing; they’re not looking for a particular behavior,” says Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University.

“They’re just looking for anything that’s soothing; they’re not looking for a particular behavior,” says Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University.

Clinicians, then, have to probe why a person engages in a particular action. That task is doubly difficult if the person cannot articulate her experience. Autistic people may lack self-insight or have verbal, communicative or intellectual challenges, which leads to misdiagnoses and missed diagnoses, like Slavin’s.

Clinicians long overlooked Slavin’s OCD and autism, although he was no stranger to a psychologist’s office growing up in the suburbs of northwest London. He did not speak for his first six years and says his memories are peppered with frequent visits to speech therapists and psychiatrists. Even after he began talking, he was socially withdrawn and disliked eye contact. He was plagued with anxieties and stomachaches.

At around 11, he was diagnosed with ‘infantile schizophrenia’ and prescribed valium and lithium. Doctors warned his parents that he might need to be institutionalized for life. Instead, he attended a progressive boarding school and graduated, as he puts it, a “slightly more functional” person. He pursued his passion for music, met his wife Bonnie and started a family.

Doctors warned his parents that he might need to be institutionalized for life. Instead, he attended a progressive boarding school and graduated, as he puts it, a “slightly more functional” person. He pursued his passion for music, met his wife Bonnie and started a family.

His autism diagnosis so many years later was empowering, he says, but it also raised new complications. When he spoke with clinicians, for example, his autism always seemed to eclipse his other challenges, including an auditory-processing disorder. “Once you’ve had a diagnosis of autism, doctors say ‘Oh, it’s because of the autism,’ and they don’t look at the nuances,” he says. He found that no one could tell him whether a particular behavior was a result of his OCD or his autism — or what to do about it.

Common biology:Answers to Slavin’s questions may emerge as more researchers study autism and OCD together. Just 10 years ago, virtually no one did that, says Suma Jacob, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. When she told people she was interested in researching both conditions, “top advisers in the field said you have to pick one,” she says. That’s changing, in part because researchers have come to appreciate how many people have both conditions.

When she told people she was interested in researching both conditions, “top advisers in the field said you have to pick one,” she says. That’s changing, in part because researchers have come to appreciate how many people have both conditions.

Jacob and her colleagues are tracking the appearance of repetitive behaviors — which could be linked to autism or OCD — by age 3 in thousands of children. “From the brain perspective, these [conditions] are all related,” she says.

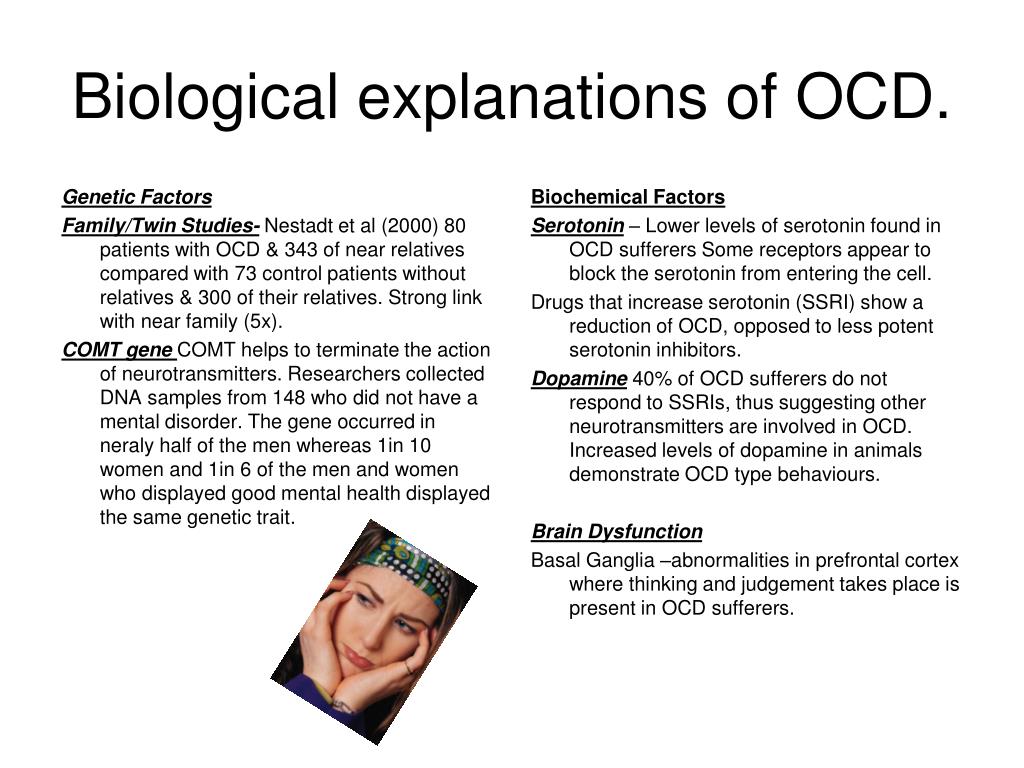

In fact, scientists have found some of the same pathways and brain regions to be important in both autism and OCD. Brain imaging points to the striatum in particular, a region associated with motor function and rewards. Some studies suggest that people with autism and people with OCD both have an unusually large caudate nucleus, a structure within the striatum.

Animal models, too, implicate the striatum. Veenstra-VanderWeele is studying autism and OCD using rodents that show repetitive behaviors. In both conditions, he and other neuroscientists have found anomalies within the brain’s cortical-striatal-thalamic-cortical loop; this system of neural circuits runs through the striatum and plays a part in how we start and stop a behavior, as well as in habit formation. Another line of inquiry highlights interneurons, which often inhibit electrical impulses between cells: Disrupting interneurons in the striatum can create twitching, anxiety and repetitive behaviors in mice that appear similar to traits of OCD or Tourette syndrome.

Another line of inquiry highlights interneurons, which often inhibit electrical impulses between cells: Disrupting interneurons in the striatum can create twitching, anxiety and repetitive behaviors in mice that appear similar to traits of OCD or Tourette syndrome.

Among male mice specifically, interfering with interneurons in the striatum also leads to sharp drops in social interaction, forging a tenuous connection to autism. “Lo and behold, the mice also had social deficits identical to what we’ve seen in [animal models] associated with autism,” says Christopher Pittenger, director of the OCD Research Clinic at Yale University, who led this work. For that reason, he says, interneurons might be a common treatment target for both autism and OCD.

Some of the shared wiring researchers are uncovering could reflect a genetic overlap. The 2015 Danish study found that people with autism are more likely than controls to have relatives with OCD. But genetic comparisons of the two conditions thus far have yielded contradictory results or been hampered by how little is known about the genetics of OCD. “We know much more about the genetics of autism than we do about OCD, almost embarrassingly so,” Pittenger says. That gap could explain why a 2018 meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies — encompassing more than 200,000 people with 25 conditions, including autism and OCD — found no shared common variants between OCD and autism.

“We know much more about the genetics of autism than we do about OCD, almost embarrassingly so,” Pittenger says. That gap could explain why a 2018 meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies — encompassing more than 200,000 people with 25 conditions, including autism and OCD — found no shared common variants between OCD and autism.

Unpublished work from another group suggests that rare ‘de novo mutations,’ which occur spontaneously, can significantly increase the risk of having autism or OCD. Some of the genes the researchers linked to both diagnoses relate to immune functioning, suggesting that an interaction between environmental factors and the immune system might play a role. Another gene on that shared list, CHD8, regulates gene expression.

“We know much more about the genetics of autism than we do about OCD, almost embarrassingly so.” Christopher PittengerAdapting treatment:

Until scientists can connect these preliminary findings to pathways, new drug treatments are a long way off. But people who have both conditions do have other routes for finding help.

But people who have both conditions do have other routes for finding help.

On a chill evening in December, people across the U.K. dial in to a monthly ‘OCD & Autism Support Group’ meeting organized by OCD Action, a U.K.-based charity for people with OCD. The group size varies from one session to the next, but on this particular night, just days before Christmas, there are only four callers.

During the session, a woman named Michelle (everyone on the call uses first names only) explains that she cannot leave the house unless she is convinced all the switches and appliances are turned off. Thomas loses hours of the day to showering. Both talk about social difficulties — and how that can make them anxious. They often worry about what people think of them and whether their repetitive behaviors, caused by OCD or autism, make them appear strange to others.

As with most support-group meetings, the call reassures its participants that they are not alone. The callers also share updates and tips, such as using a timer to cut down on the time spent on hand-washing. Three of the callers mention CBT, which can help people understand and manage their obsessions and compulsions. As with other talk therapies, though, CBT isn’t always effective for people with autism. The therapy did not help Slavin, for example.

Three of the callers mention CBT, which can help people understand and manage their obsessions and compulsions. As with other talk therapies, though, CBT isn’t always effective for people with autism. The therapy did not help Slavin, for example.

He suspects that he was unable to follow his therapist’s approach due to his auditory-processing difficulties and cognitive inflexibility, which he attributes to his autism. “Many people on the spectrum have a problem picturing a situation and picturing how it could have a different outcome, so traditional CBT doesn’t always work,” he says. Slavin instead manages his OCD — with mixed success — using antidepressants.

Some researchers are trying to adapt CBT for people with autism by, among other things, “making sure that somebody can notice and rate their emotional state,” Russell says. Working with her colleagues at King’s College London, Russell found in a pilot study that the modified methods help some adults with both autism and OCD manage their anxiety. Drawing on the success of a subsequent larger trial, she and her colleagues published a guide for clinicians in January.

Drawing on the success of a subsequent larger trial, she and her colleagues published a guide for clinicians in January.

A more personalized variation of CBT might also work for people who have both autism and OCD. Various schemes include involving parents in sessions, adjusting the language to meet an autistic person’s ability, using visuals and offering children rewards. One trial is comparing these adaptations with standard CBT in more than 160 children who have both autism and OCD. The unpublished results suggest that standard CBT is beneficial, but an individualized approach is best of all.

Slavin sees the merits of more personalized treatment options, although he hasn’t tried it himself. Working with OCD Action and nonprofit advocacy groups for autism, he has come to appreciate the diversity that exists in both conditions. “It’s almost like you need a different diagnosis for every single person, a different category for every single person, because everyone is so different,” he says.

A decade after his autism diagnosis, Slavin is eager to share his experiences, in part to counteract the lack of resources he initially faced. In 2010, he launched a website and, later, a YouTube series to describe what he has learned about life with autism.

“I just see [autism] as a set of circumstances that you can use to your benefit to say ‘Okay, I’m going to forgive myself if I don’t quite understand things in the way other people do,’” Slavin says. “You can almost enjoy being a bit quirky, a bit different in some ways … [but] OCD, there’s just nothing good about that.”

In October, he published a book that chronicles the progress he has made. For now, at least, the book’s title begins: “Looking for Normal.”

Cite this article: https://doi.org/10.53053/PEUU3791

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

TAGS: anxiety, autism, behavioral interventions, depression, diagnosis, neural circuits, OCD, social difficulties, treatments

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and autism

03/05/19

Autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) often coexist, scientists are trying to study both disorders in order to better differentiate them and determine more effective treatment

Author Daisy Yuhas

Source: Spectrum News

Steve Slavin was 48 years old when a visit to a psychologist forced him to dramatically change his ideas about his own life. He had a very difficult year. Slavin began to suffer from anxiety, which manifested itself in negative thoughts and repetitive actions, and this was not the first time he suffered from them.

He had a very difficult year. Slavin began to suffer from anxiety, which manifested itself in negative thoughts and repetitive actions, and this was not the first time he suffered from them.

As a child, he could not enter a room unless he had swallowed an even number of times beforehand, and he had to swallow and count to four, six, or eight with one foot up before stepping on a stone in the pavement. As an adult, he often experienced a lot of stress around other people, and he washed his hands again and again because he was terrified of catching something from other people. He also often suffered from depression, due to which he began to avoid acquaintances and friends.

This time his depression and anxiety got worse and his doctor referred him to a psychologist. “I spent weeks, if not months, trying to get an appointment with him,” he recalls. However, within the first 10 minutes of the meeting, the psychologist suddenly stopped asking him about his childhood and current mental health issues, and instead asked him what he knew about autism.

Coincidentally, a relative had spoken to Slavin about autism just two days earlier, suggesting that this might explain his dislike of social situations. Slavin knew almost nothing about autism, but suggested that it was possible. By the end of the consultation, the psychologist was practically certain that “I either have high-functioning autism or some kind of brain damage,” Slavin recalls, chuckling. Only a few years later, the doctor gave him an official diagnosis - obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). He was also confirmed to have autism.

At first glance, autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder seem to have nothing in common. However, doctors and researchers talk about the intersection of these two disorders. Research data indicate that up to 84% of autistic people suffer from some type of anxiety disorder, and up to 17% of people with autism have OCD. And according to one 2017 study, even more people with OCD have undiagnosed autism.

Part of this overlap may be due to misdiagnosis: OCD-induced rituals may resemble repetitive behaviors in autism, and vice versa. However, there is growing evidence that many people, like Slavin, have both disorders. A 2015 study that analyzed the health records of 3.4 million Danish people over 18 years found that as adults, people with autism are twice as likely to be diagnosed with OCD than people without autism. Similarly, the same study found that people with OCD were four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism as adults than people without OCD.

However, there is growing evidence that many people, like Slavin, have both disorders. A 2015 study that analyzed the health records of 3.4 million Danish people over 18 years found that as adults, people with autism are twice as likely to be diagnosed with OCD than people without autism. Similarly, the same study found that people with OCD were four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism as adults than people without OCD.

Over the past ten years, researchers have begun to study the combination, interaction, and differences between these two disorders. Understanding these differences is important not only for making a correct diagnosis, but also for choosing an effective treatment. It appears that the experience of people with OCD and autism is unique, different from that of people with one of these disorders. And for these people, standard OCD treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), may not be effective.

Missed diagnoses

Anyone can develop obsessive thoughts (obsessions) or obsessive actions (compulsions). Many people start worrying about not turning off the stove at home, or checking again that they took their keys with them. "It's part of a normal life experience," says Ailsa Russell, a clinical psychologist at the University of Bath in the UK.

Many people start worrying about not turning off the stove at home, or checking again that they took their keys with them. "It's part of a normal life experience," says Ailsa Russell, a clinical psychologist at the University of Bath in the UK.

Most people can get over these unpleasant obsessions and go on with their normal lives. However, with obsessive-compulsive disorder, such anxiety becomes stronger and begins to interfere with normal daily functioning.

Some people with OCD, like Slavin, count steps or breaths or perform other meaningless actions because they feel that without these actions, something terrible is bound to happen. Other people call themselves "inspectors" - they check again and again that they have done a task correctly, and this prevents them from doing other things. Other people with OCD are constantly bathing or scrubbing because they are afraid of dirt or contamination.

"Typically, people with OCD are aware that their fears and behavior are irrational," says Russell, despite this OCD sufferer is trapped in intense anxiety and compulsive rituals.

The intersection between OCD and autism is still poorly understood. According to a 2015 analysis, people with both disorders are characterized by non-standard sensory responses. For some autistic people, sensory overload is the main source of stress and anxiety. For example, Slavin is terrified of police sirens and doorbells, he says that for his nervous system they are like bomb explosions.

Some researchers say that the social problems of people with autism can increase their anxiety, which in turn can lead to OCD. Failure to interpret social cues can lead to social isolation or bullying by others, which increases anxiety. “Separating anxiety from autism is extremely difficult,” says Roma Vasa, director of mental health services at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, USA.

These commonalities can make it difficult to distinguish between symptoms of autism and OCD. Even for an experienced clinician, OCD compulsions can resemble the “sameness seeking” or repetitive behaviors of autistic people, which may include tapping, lining up objects, or striving to always walk in the same path. Separating the two states can be a daunting task.

Separating the two states can be a daunting task.

As the 2015 analysis showed, the key difference is that obsessive thoughts (obsessions) lead to obsessive actions (compulsions), but not to autistic symptoms. Another feature is that people with OCD cannot, in principle, replace their rituals with other actions. In Vasa's words: "They need to do everything in a certain way, otherwise they experience anxiety and discomfort."

At the same time, autistic people tend to have a repertoire of different repetitive behaviors that serve a similar function and from which to choose. “They just go for any behavior that helps them calm down, it doesn’t really matter to them any particular action,” says Jeremy Winstra-Vanderviel, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, USA.

Thus, doctors need to determine why a person performs a particular action. But this task becomes difficult if it is difficult for the patient to describe his experience in words. Autistic people may have speech, communication, or intellectual impairments and often have significant difficulty identifying and understanding their inner experiences. This can lead to misdiagnosis, as happened in the case of Slavin.

This can lead to misdiagnosis, as happened in the case of Slavin.

As a child, Slavin often visited a psychologist's office in the suburbs of London. However, the experts who examined him missed both OCD and autism. Slavin did not speak until the age of 6. According to him, his first childhood memories are classes with a speech therapist and a child psychologist. Even after he started talking, he avoided other people and didn't like making eye contact. He suffered from severe anxiety and abdominal pain.

At about 11 years of age, he was diagnosed with "childhood schizophrenia" and was prescribed Valium and lithium. Doctors warned his parents that he might need a lifelong stay in a medical facility. Instead, he was able to attend a prestigious high school, get a degree and become, in his words, a "slightly more functional" person, and thanks to his passion for music, he was able to launch a career as a professional composer.

Being diagnosed with autism many years later brought him great relief, but it was also associated with new problems. During conversations with specialists, for example, they began to attribute any of his complexities to autism, including problems with the perception of auditory information. “Once you get this diagnosis, the doctors start saying, ‘Well, it’s because of autism,’ they don’t pay attention to the nuances,” he says. Slavin found that no one can say for sure whether a particular behavior is the result of OCD or autism, or what exactly can be done about it.

During conversations with specialists, for example, they began to attribute any of his complexities to autism, including problems with the perception of auditory information. “Once you get this diagnosis, the doctors start saying, ‘Well, it’s because of autism,’ they don’t pay attention to the nuances,” he says. Slavin found that no one can say for sure whether a particular behavior is the result of OCD or autism, or what exactly can be done about it.

General Biology

Slavin's questions may be answered soon as more researchers look at the combination of autism and OCD. Until 10 years ago, research on this topic was practically non-existent, says Suma Jacob, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota, USA. When she said she was interested in studying the two disorders, "the main experts in the field said to pick one disorder," she says. This situation is starting to change, in part because researchers have begun to realize how common it is to combine autism and OCD.

Jacob and colleagues have been tracking repetitive behaviors (which may be associated with autism or OCD) in thousands of children as young as 3 years old. “From a brain perspective, all these disorders are connected,” she says.

In fact, scientists have found that the same brain regions and neural pathways play an important role in both autism and OCD. Brain scans point to a special role for the striatum, an area of the brain that is associated with motor functions and rewards. Some research suggests that in people with autism and people with OCD, one structure within the striatum, the caudate nucleus, is larger than normal.

Animal models also suggest a role for the striatum. Winstra-Vanderwil studies autism and OCD with repetitive behavior rodents. He and other scientists found that in both disorders, the animals show abnormalities in the neural circuitry that runs through the striatum and plays a key role in how we start and stop behavior, as well as influencing habit formation.

Another area of research is related to interneurons, which often suppress impulses between cells. If the interneurons in the striatum of mice are disrupted, this leads to twitching, anxiety, and repetitive behavior that resembles OCD and Tourette's syndrome.

In male mice, the impact on the functioning of interneurons also leads to a sharp decrease in sociability, which, to some extent, may resemble autism. "Unexpectedly, mice also developed social deficits identical to those we see in animal models of autism," says Christopher Pittenger, director of the OCD Research Clinic at Yale University, who led the work. For this reason, he says, interneurons could be a target for both OCD and autism treatments.

This connection at the level of neural pathways may reflect common genetic causes. A 2015 Danish study found that people with autism were more likely to have relatives with OCD than people in a control group. However, genetic comparisons of the two disorders have shown conflicting results at this stage, which may be due to the fact that very little is known about genetic factors in OCD. “As embarrassing as it is to admit, we know a lot more about the genetics of autism than we do about the genetics of OCD,” says Pittenger. A similar gap may explain why a 2018 meta-analysis of genome studies of more than 200,000 people with 25 disorders, including autism and OCD, found no common gene variants for OCD and autism.

“As embarrassing as it is to admit, we know a lot more about the genetics of autism than we do about the genetics of OCD,” says Pittenger. A similar gap may explain why a 2018 meta-analysis of genome studies of more than 200,000 people with 25 disorders, including autism and OCD, found no common gene variants for OCD and autism.

Unpublished work by another research group suggests that rare “de novo mutations,” that is, spontaneous mutations that neither parent has, significantly increase the risk of autism and OCD. Some of the genes that researchers have linked to both diagnoses are related to the immune system. This suggests that interactions between environmental factors and the immune system may play a role. Another gene from the general list, CHD8, regulates gene expression.

Treatment adaptation

Until scientists can combine all the data from the preliminary studies, no new drugs can be expected. But there are other methods that can help people with both disorders.

On a chilly December evening, people from all over the UK join the OCD & Autism Support Group, a monthly online conference organized by OCD Action, a British charity that helps people with OCD. The number of group members varies greatly during each meeting, but this evening, a few days before Christmas, only four people called.

During the meeting, a woman named Michelle (only given names in the group) explains that she cannot leave the house unless she makes sure all the lights and appliances are turned off. Thomas spends several hours a day showering. Both of them talk about social difficulties and how they make them anxious. They often worry about what other people think of them, and whether others find their behavior related to OCD or autism strange.

Like most support groups, calling together helps participants feel they are not alone. They also share new information and tips, such as how to use a timer to reduce the time spent washing your hands. Three of the participants mention cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which can help people better understand and manage their obsessive thoughts and actions. As with other forms of psychotherapy that rely on dialogue, it may not be effective for people with autism. For example, such psychotherapy did not help Slavin.

As with other forms of psychotherapy that rely on dialogue, it may not be effective for people with autism. For example, such psychotherapy did not help Slavin.

He suspects that he was unable to follow the therapist's methods because of his difficulty with listening to speech and lack of mental flexibility, which he attributes to autism. “Many people on the autism spectrum find it difficult to imagine the situation and how it could lead to a different outcome, so traditional CBT doesn't always work,” he says. Instead, Slavin controls OCD with varying degrees of success with antidepressants.

Some researchers are trying to adapt CBT for people with autism, such as "making sure everyone can see and appreciate their own emotional state," says Russell. Together with her colleagues at King's College London, Russell found in a preliminary study that modified methods may help some adults with autism and OCD manage their anxiety. In January of this year, she and her colleagues, building on the success of the subsequent larger study, developed a clinical guideline.

People with autism and OCD can also benefit from a more personalized approach to cognitive behavioral therapy. For example, possible schemes might include parent participation in counseling, language facilitation according to the person's language ability, use of visual support and rewards. One clinical trial compared this adapted therapy with standard CBT in more than 160 children with autism and OCD. As yet unpublished results suggest that standard CBT may be beneficial, but an individualized approach works best.

It seems to Slavin that a more individual approach to treatment can be successful, but he himself has not tried such approaches. Working with organizations that help people with OCD and people with autism, he began to appreciate the diversity of people with both disorders. “It feels like every single person needs their own diagnosis, their own category, because everyone is so different,” he says.

Ten years after being diagnosed with autism, Slavin wants to share his experience, also in order to combat the lack of resources he has faced. In 2010, he opened a website and started a YouTube channel where he talks about what he has learned about living with autism.

In 2010, he opened a website and started a YouTube channel where he talks about what he has learned about living with autism.

“I just think of autism as a certain set of circumstances that you can use to your advantage and say, 'OK, I'm going to forgive myself if I don't quite understand how other people act,'” says Slavin. “You can even find joy in your oddities and differences from others ... But OCD, there is nothing good about it at all.”

In October he published a book on his progress. So far, the title of the book sounds like "The search for the norm."

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Research, Psychiatry, Comorbidities

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder or "Just Autism"?

05/18/14

Psychiatrist on differential diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder in autism

Source: Autism Speaks

for children with an autistic spectrum of typical, or something, or something is the same. preoccupation with some object, toy, video, task, and so on. Sometimes it is difficult for parents to determine whether such preoccupation is a manifestation of autism or whether it is behavior associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Children with autism can also be diagnosed with OCD. Below, Dr. Judy Riven explains how you can find out if your child needs to be tested for this disorder.

preoccupation with some object, toy, video, task, and so on. Sometimes it is difficult for parents to determine whether such preoccupation is a manifestation of autism or whether it is behavior associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Children with autism can also be diagnosed with OCD. Below, Dr. Judy Riven explains how you can find out if your child needs to be tested for this disorder.

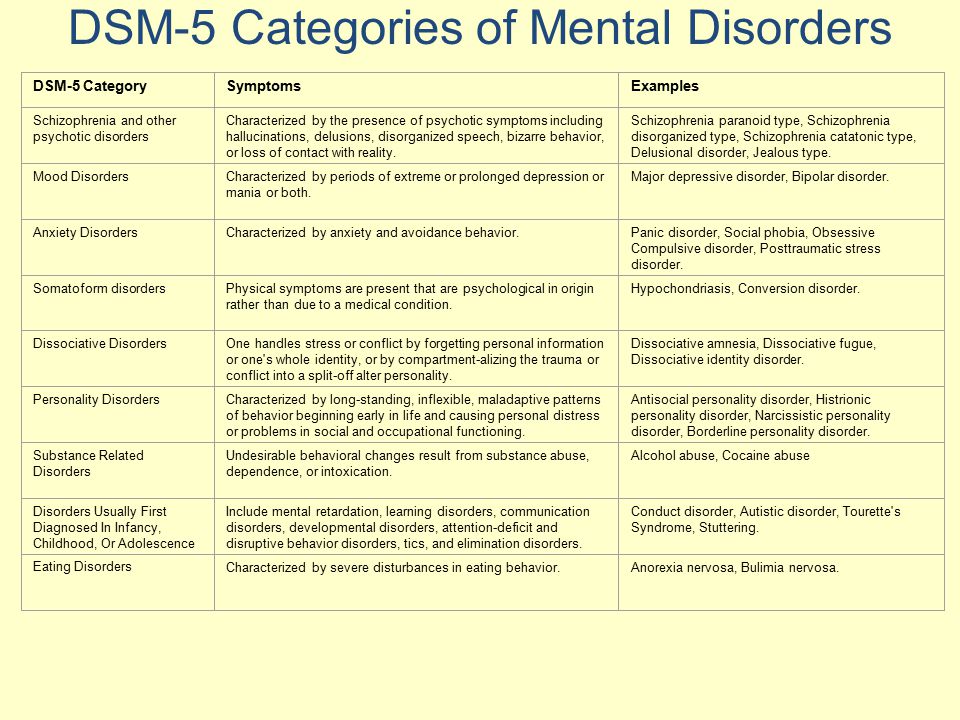

Several psychological disorders, including obsessive compulsive disorder or OCD, are common in autism. However, on the other hand, some of the symptoms of autism resemble those of other disorders, including OCD. So it can be difficult to separate the manifestations of autism in a given patient from the symptoms of another disorder.

As the name suggests, OCD includes obsessions (unwanted, intrusive thoughts), compulsions (unwanted, compulsive actions), or both. Obsessions are involuntary thoughts appearing at regular intervals that are both intrusive and undesirable for a person. Obsessions cause very strong stress, but at the same time a person cannot ignore them. Very often, people suffering from obsessional thoughts try to reduce the discomfort they cause by performing a specific action (often ritualistic). Such actions, which allow temporary relief of obsession, are called compulsive actions. Compulsions are repetitive, repetitive actions that take a person a considerable amount of time, but the person feels that he “must” perform this or that action in response to an unpleasant intrusive thought, even if from the outside this behavior seems meaningless.

Obsessions cause very strong stress, but at the same time a person cannot ignore them. Very often, people suffering from obsessional thoughts try to reduce the discomfort they cause by performing a specific action (often ritualistic). Such actions, which allow temporary relief of obsession, are called compulsive actions. Compulsions are repetitive, repetitive actions that take a person a considerable amount of time, but the person feels that he “must” perform this or that action in response to an unpleasant intrusive thought, even if from the outside this behavior seems meaningless.

Obsessions or special interests?

OCD is often confused with special interests or repetitive activities that are a feature of autism. However, the symptoms of these conditions are actually very different. Obsessive interests in autism, as a rule, bring joy and pleasure to a person. OCD is more of a behavior that a person engages in just to reduce overwhelming stress or anxiety.

It is impossible to understand what exactly is happening to a person without a complete examination. Not too long ago, I had a conversation with the mother of a 25-year-old young man with autism who was worried about her son. She told me that although her son has always had repetitive behaviors, lately he constantly wants to redo different tasks, such as dressing again or taking a shower, even if he just took it. He also insists that their car be turned back if they just drove down a different street. I noticed two features that led me to believe that she was describing possible symptoms of OCD.

Not too long ago, I had a conversation with the mother of a 25-year-old young man with autism who was worried about her son. She told me that although her son has always had repetitive behaviors, lately he constantly wants to redo different tasks, such as dressing again or taking a shower, even if he just took it. He also insists that their car be turned back if they just drove down a different street. I noticed two features that led me to believe that she was describing possible symptoms of OCD.

First, she noted that this behavior was significantly different from her child's past behavior that was associated with autism. Second, she described an increase in the severity of his symptoms. Finally, the description of her son's behavior matched the typical OCD symptom of getting stuck on something because it feels "wrong." In order to “fix” something, a person with OCD has to “re-do” something. For example, in this young man's case, he felt compelled to re-shower or re-dress. It also suited his need to drive the "right" way.

We have effective therapy!

If the new symptoms meet the criteria for an official diagnosis of OCD, the person may benefit from special treatment. In particular, a vast body of research has shown that cognitive behavioral therapy can help people with autism manage OCD symptoms. (Editor's note: Dr. Riven is one of the first practitioners to adapt cognitive behavioral therapy for people with autism.)

This psychotherapy involves helping the person become aware of their obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors and identify them as such. For example, a person can learn to recognize the physical symptoms of stress associated with obsessions. In CBT, we explain that thoughts can affect physical well-being and vice versa.

More importantly, we provide the patient with useful tools for managing problematic symptoms. This may include deep breathing and repeating positive affirmations, such as, “It's just OCD. I can handle it."

In the case of OCD, an important part of CBT is contact/reaction prevention.