Introverted teacher burnout

Teacher Burnout Is More Likely Among Introverts

Education

Educators are feeling drained by the insistent emphasis on collaboration and “social learning”—and that could be undermining kids’ achievement.

By Michael GodseyDarkBird / Shutterstock / Kara Gordon / The AtlanticJayson Jones was my favorite person to call when I needed a substitute for my high-school English classes. Jayson was an aspiring teacher who was extremely popular with the students and related especially well with many of the at-risk kids. One day, I walked into the classroom at lunchtime, and he was sitting alone in the dark, listening to music. “Oh, an introvert?” I said. “I had no idea.” He smiled and responded, “Absolutely. I do this every day to recharge.” Unfortunately for me and thousands of future students, Jayson has left the classroom for the workshop: He’s refurbishing furniture instead of teaching and says that his “introversion definitely played a part.

”

I’ve written about the challenges faced by introverted students in today’s increasingly social learning environments, but the introverted teachers leading those classrooms can struggle just as much as the children they’re educating. A few studies suggest that introverted teachers—especially those who may have falsely envisioned teaching as a career involving calm lectures, one-on-one interactions, and grading papers quietly with a cup of tea—are at risk of burning out. And when these teachers leave for alternate careers, it comes at a cost to individual children and school districts at large.

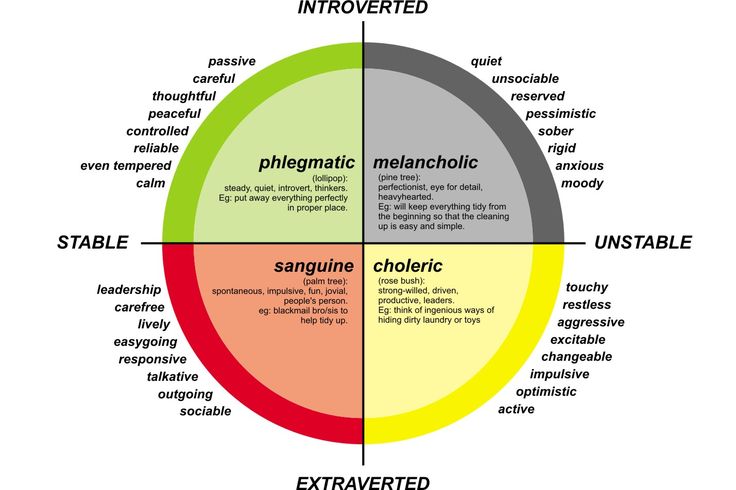

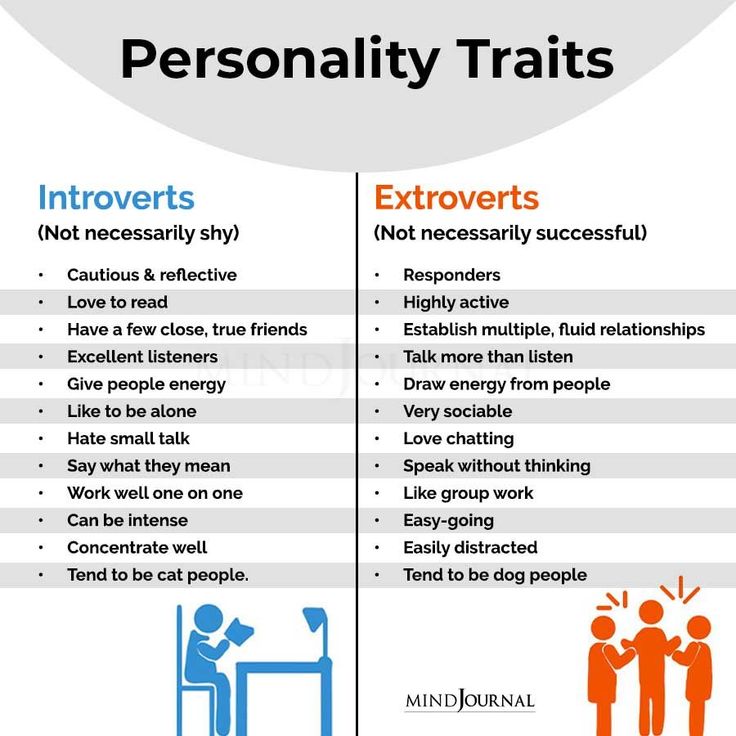

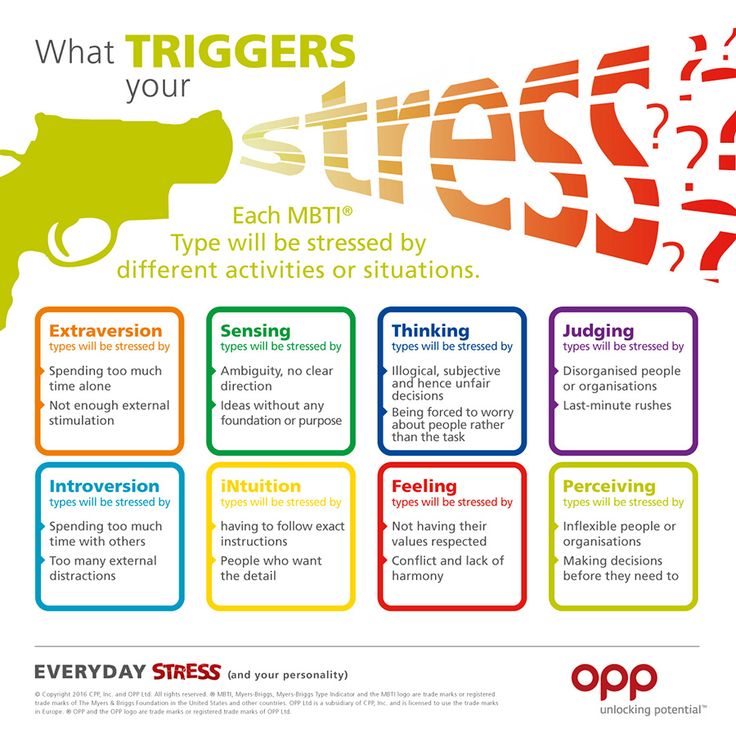

The term “introversion” can mean a variety of different things in different contexts. Carl Jung defined it as an orientation through “subjective psychic contents,” while Scientific American contends that introversion is more aptly described as a lessened “sensitivity to rewards in the environment.” It’s generally accepted, however, that as Stephen A. Diamond gracefully describes it, “[Extraversion and introversion] are two extreme poles on a continuum which we all occupy. ”

”

The most common use of the term is to differentiate between introverts (who are energized by quiet space, introspection, and deep relationships and are exhausted by excessive social interactions) and extroverts (who are energized by social interaction and external stimulation and tend to be bored or restless by themselves) as a way of explaining different personal reactions to similar contexts.

It’s in this sense of the word that some teachers are citing their introversion as a reason why today’s increasingly social learning environments are exhausting them—sometimes to the point of retirement.

After 11 years of teaching English at a public high school, Ken Lovgren left the profession, mostly because he was drained by the insistent emphasis on collaboration and group work. Engaging in a classroom that was “so demanding in terms of social interaction” made it difficult for him to find quiet space to decompress and reflect. “The endless barrage of ‘professional learning community’ meetings left me little energy for meaningful interaction with my kids,” he told me. “I suspect a lot of teachers feel as I do.”

“I suspect a lot of teachers feel as I do.”

In fact, it was easy to find other teachers who cited their introversion as a key reason they decided to leave the K-12 classroom. John Spencer, a former middle-school teacher who has written about the struggles of an introverted teacher, is now teaching at a university. “It’s easier to be a professor as an introvert,” he said. “There’s so much silence and solitude built into it.”

And Jessica Honard, the author of the book Introversion in the Classroom: How to Avoid Burnout and Encourage Success, told me that she left the teaching profession because she never had the time to recharge after constant exposure to such a stimulating environment. Claiming that she’s known many other teachers who have left because of exhaustion, Honard primarily blamed a lack of awareness and understanding of introverted personality types. She explained: “It’s a constant bombardment of social stimulation, and most teachers simply are not taught how to cope with it. ”

”

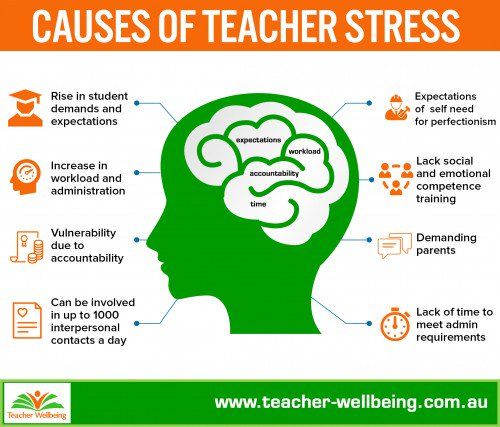

In some ways, today’s teachers are simply struggling with what the Harvard Business Review recently termed “collaborative overload” in the workplace. According to its own data, “over the past two decades, the time spent by managers and employees in collaborative activities has ballooned by 50% or more.” The difference for teachers in many cases is that they don’t get any down time; they finish various meetings with various adults and go straight to the classroom, where they feel increasing pressure to facilitate social learning activities and promote the current trend of collaborative education.

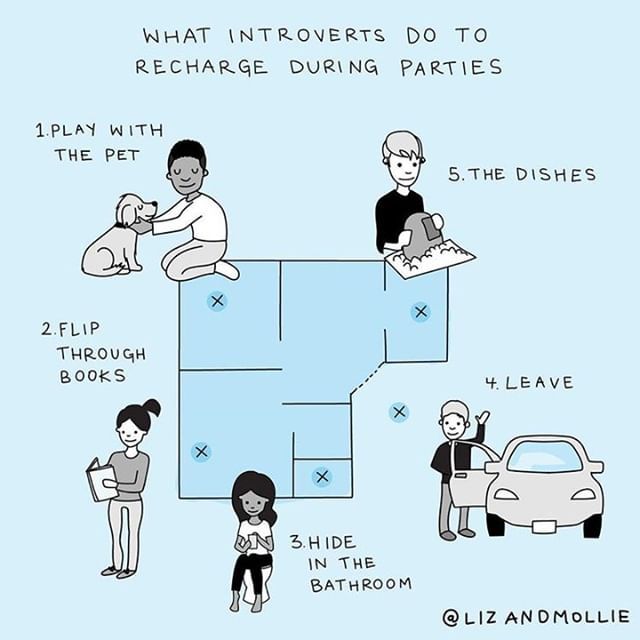

This type of schedule and expectation for constant social interaction negates the possibility to psychologically “recharge” in relative solitude, something that’s crucial to many introverts. Lovgren described his lunches alone in the sunshine as a place “to be alone and recharge … to think about big ideas and prepare something worthwhile to say to the kids during discussion. ” Spencer wrote that introverted teachers in general may eat alone at lunch because they’re “tired of being ‘on’ all the time … [and] they simply need time to recharge.” Brian Little, a widely acclaimed speaker and psychology professor at Cambridge University, refers to these opportunities to recharge as “restorative activities.” In a 2005 article, he wrote that “for a biogenic introvert who has been protractedly acting out of character as a ‘pseudo-extravert’ the best restorative niche would be one of solitude and reduced stimulation.”

” Spencer wrote that introverted teachers in general may eat alone at lunch because they’re “tired of being ‘on’ all the time … [and] they simply need time to recharge.” Brian Little, a widely acclaimed speaker and psychology professor at Cambridge University, refers to these opportunities to recharge as “restorative activities.” In a 2005 article, he wrote that “for a biogenic introvert who has been protractedly acting out of character as a ‘pseudo-extravert’ the best restorative niche would be one of solitude and reduced stimulation.”

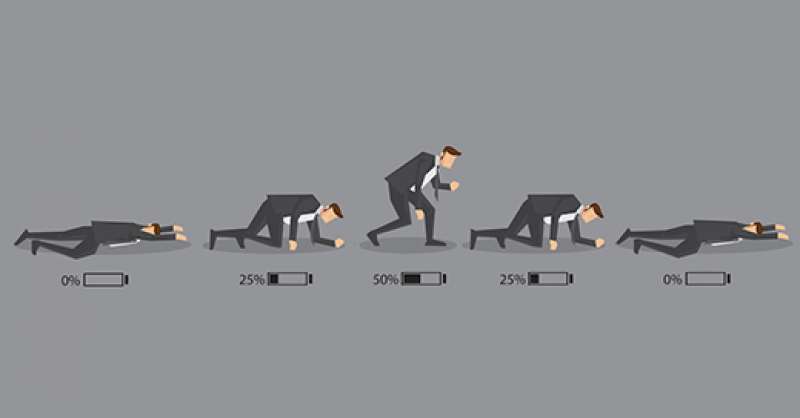

In the same article, Little explained how introverts can “act as extraverts” and adopt culturally scripted behavior traits (what he calls “free traits”) for limited amounts of time. But he warned that “protracted free-traited behavior may compromise emotional and physical health.” In other words, Little’s findings confirm that introverted teachers are at risk of burning out.

“It’s easier to be a professor as an introvert. There’s so much silence and solitude built into it. ”

”Although the reasons for burnout are varied and hard to pinpoint, some statistics suggest that 41 percent of teachers leave the profession within five years of entering it. Teacher attrition among first-year teachers has increased about 40 percent in the past two decades—a trend that’s coincided in part with the growing emphasis in classrooms on cooperative and student-driven learning and on “collaborative overload” in general.

A range of factors such as morale, accountability expectations, and salaries certainly contribute to the attrition problems. However, one study by researchers in Spain showed that the structure of a teacher’s personality predicted burnout more strongly than other types of factors. As school districts reportedly spend $2.2 billion annually on educator attrition, it’s worth considering how to better respond to the range of other factors that help explain teachers’ dissatisfaction, including introverted personality tendencies that aren’t always compatible with modern pedagogical trends.

At least a handful of recent studies actually confirm this connection between burnout and introversion. Barbara Larrivee’s book Cultivating Teacher Renewal: Guarding Against Stress and Burnout cites five different analyses that show “being introverted predicts burnout” in the general workplace. The Spanish researchers’ study examined the teaching profession in particular, and found that “teachers with high scores in emotional exhaustion” associated with “low scores in extraversion.” The same report, in agreement with several other studies it cited, concluded that introversion “means characteristics that foster emotional exhaustion … while they diminish personal accomplishment.” Meanwhile, introverted teachers have regularly written about how they miss the traditional lecture format, about how they almost quit teaching, and about how they did in fact leave teaching for a job more suitable for introverts.

In order to slow the rate of teacher attrition, some people are recommending more induction programs for new teachers. However, this seems to—once again—overlook the needs of introverted teachers. I wouldn’t even classify myself an introvert, and the school where I work is extremely respectful of each teacher’s personal style. But I remember, as a new teacher, the overwhelming number of interactions that were ostensibly designed to help me—support classes, beginning teacher programs, department meetings, union mixers, “Back to School Night,” constant public introductions, and administrative observations. I remember desperately yearning to just quietly study Hamlet and read my new students’ papers.

However, this seems to—once again—overlook the needs of introverted teachers. I wouldn’t even classify myself an introvert, and the school where I work is extremely respectful of each teacher’s personal style. But I remember, as a new teacher, the overwhelming number of interactions that were ostensibly designed to help me—support classes, beginning teacher programs, department meetings, union mixers, “Back to School Night,” constant public introductions, and administrative observations. I remember desperately yearning to just quietly study Hamlet and read my new students’ papers.

During that same year, the district assigned to me a mentor to help orient me—he took me out to coffee, and we just talked about good literature and lesson ideas for an hour. The principal, visibly flustered that we didn’t observably “do anything,” assigned me a new mentor who, among other things, encouraged me to divide my class into cooperative groups and then share the results with my department and administration. The implicit message seemed to be similar to what Lovgren said explicitly: “A calm and focused teacher is suspected of underworking, and so everybody, regardless of their personality type, is expected to work constantly in groups.”

The implicit message seemed to be similar to what Lovgren said explicitly: “A calm and focused teacher is suspected of underworking, and so everybody, regardless of their personality type, is expected to work constantly in groups.”

The primary concern, as always, is for the students, many of whom are introverts themselves and in want of role models and sympathizers in a culture that sometimes misunderstands kids who are seemingly “unwilling to stand up for themselves.” Perhaps teachers and administrators who tend to be introverted themselves can instinctively provide the space the quiet student needs, and also model and value more reserved behavior. Teachers in Robert Coplan’s 2001 study “believed that shy/quiet children were less intelligent and would do more poorly academically than would exuberant/talkative children. However, some of these findings were moderated by teachers' own level of shyness.”

Coplan’s careful use of the phrase “level of shyness” is a good reminder that introversion and extroversion are not diametrically opposed in black and white fashion; and in any case, people’s personalities shift depending on the time and situation. As Jill Burruss and Lisa Kaenzig explained in their paper for the College of William and Mary, “Most people utilize both introversion and extraversion in their daily lives … no one list [of personality traits] adequately captures the uniqueness of any individual, but serves as a beginning guide to recognizing and understanding behaviors.” And in many cases, people have similar needs: While writing about an introvert’s need for solitude, Spencer conceded, “I think everyone can benefit from the lack of social distractions.”

As Jill Burruss and Lisa Kaenzig explained in their paper for the College of William and Mary, “Most people utilize both introversion and extraversion in their daily lives … no one list [of personality traits] adequately captures the uniqueness of any individual, but serves as a beginning guide to recognizing and understanding behaviors.” And in many cases, people have similar needs: While writing about an introvert’s need for solitude, Spencer conceded, “I think everyone can benefit from the lack of social distractions.”

With that said, people’s behavior does tend to cluster toward certain tendencies, and Burruss and Kaenzig reported that, with all the social interaction, group activities, common spaces, and noisy activities, “modern school seems designed for extraverts.”

“A calm and focused teacher is suspected of underworking.”In order to say something worthwhile about big ideas, Lovgren said, many people need significant time and space for prior reflection—and any implication that active group work is categorically superior alienates those students and teachers. Like many if not most introverts, Lovgren isn’t anti-social, or even anti-collaboration; he’s just asking for less social stimulation and more freedom to think quietly. “If you give me time and space to complete the task in my own way, I’ll come back to the group with a quality contribution.”

Like many if not most introverts, Lovgren isn’t anti-social, or even anti-collaboration; he’s just asking for less social stimulation and more freedom to think quietly. “If you give me time and space to complete the task in my own way, I’ll come back to the group with a quality contribution.”

It’s also reasonable to assume that students will be better off when each of their respective teachers are in an environment that suits their teaching style. As the English teacher Abigail Walthausen explained in The Atlantic two years ago, “If the community of educators has agreed to value student learning styles, why not allow adults the freedom to play to their own strengths as well? I certainly know that while I am articulate in facilitating student discussion, my communication breaks down and I am a weaker teacher in a noisy room.”

Earlier this month, Spencer, the former middle-school teacher who’s documented his struggles as an introvert, wrote a popular blog post on “re-imagining school” for educators like him that offers some suggestions on how K-12 campuses can meet the needs of teachers who are less extroverted, from “providing professional development credit for personal learning” to simply offering them some options in regards to collaborative activities. Embracing ideas like these, schools could better accommodate the different personality types of their teachers; reduce burnout and save money on attrition; and foster an educational environment that encourages and cherishes introspective reflection within the students themselves.

Embracing ideas like these, schools could better accommodate the different personality types of their teachers; reduce burnout and save money on attrition; and foster an educational environment that encourages and cherishes introspective reflection within the students themselves.

Related Video

How do you fix a school where only 22 percent of students are at grade level?

Schools Need Introverted Teachers, But Avoiding Burnout a Challenge

By: Tim Walker

Published: 02/04/2016

It's generally believed that the teaching profession is better suited to extroverts. While hugely rewarding, it is exceptionally demanding, noisy, chaotic and educators are always under the microscope. But there are many introverted teachers across the country, who, as a recent article in The Atlantic concluded, are more vulnerable to burnout than their extroverted colleagues.

Jessica Honard agrees. A self-described introvert, Honard left the classroom after five years after she reluctantly concluded that the relentless daily pressure eclipsed what she loved about teaching high school English. She continued to work in education, including leading workshops for educators on how to differentiate for introverted students. After these sessions, participants would approach Honard and tell her that they were introverted teachers and were just as burned out as their students. "I soon realized that there was this community out there of introverted teachers who were overwhelmed," she recalls. Honard was already writing a book about working with introverted students but decided to include a section offering tips and strategies to help introverted teachers navigate the school day. The book is called "Introversion in the Classroom: How to Avoid Burnout and Encourage Success" and Honard spoke with NEA Today recently about her experiences and the challenges introverted teachers face.

She continued to work in education, including leading workshops for educators on how to differentiate for introverted students. After these sessions, participants would approach Honard and tell her that they were introverted teachers and were just as burned out as their students. "I soon realized that there was this community out there of introverted teachers who were overwhelmed," she recalls. Honard was already writing a book about working with introverted students but decided to include a section offering tips and strategies to help introverted teachers navigate the school day. The book is called "Introversion in the Classroom: How to Avoid Burnout and Encourage Success" and Honard spoke with NEA Today recently about her experiences and the challenges introverted teachers face.

In your first year in the classroom, were you prepared for the pressures of teaching? Were you consciously aware that you were an introvert?

Jessica Honard: No. At the time - I was very young - I didn't really know what introversion was, at least not until I read Susan Cain's book "Quiet" the year after I left teaching. So I didn't know why I got burned out so easily and overwhelmed so quickly. I did experience something similar in high school, and my solution then was to enroll in community college and distance myself from the social aspects of high school. So when I began to teach, I was kind of expecting it to be overwhelming because you do hear a lot about teacher burnout. It's the nature of the field. I do think that introverts and extroverts are both susceptible to burnout, but I think introverts are a little bit more so.

At the time - I was very young - I didn't really know what introversion was, at least not until I read Susan Cain's book "Quiet" the year after I left teaching. So I didn't know why I got burned out so easily and overwhelmed so quickly. I did experience something similar in high school, and my solution then was to enroll in community college and distance myself from the social aspects of high school. So when I began to teach, I was kind of expecting it to be overwhelming because you do hear a lot about teacher burnout. It's the nature of the field. I do think that introverts and extroverts are both susceptible to burnout, but I think introverts are a little bit more so.

What were the conditions at your school that made it particularly hard for you?

JH: I loved teaching. I loved being in the classroom and I particularly enjoyed connecting with the students, but I felt I wasn’t given enough time to do more of that. For a short period of time, I was the only teacher in my subject and then they added another one, which alleviated the class size problem. But I still had around 190-210 students, which for me was a lot. For my students it was a lot too, because they were coming at me at all different ability levels and it was hard for me to reach them that way. Plus, the constant meetings and the expectations that the administration had - which weren't necessarily bad but they often took more time than I had to give - became too much. Eventually, when you have enough 13,14, 15 hour days, you have to pull back and ask yourself if this is the way you want to approach this field.

But I still had around 190-210 students, which for me was a lot. For my students it was a lot too, because they were coming at me at all different ability levels and it was hard for me to reach them that way. Plus, the constant meetings and the expectations that the administration had - which weren't necessarily bad but they often took more time than I had to give - became too much. Eventually, when you have enough 13,14, 15 hour days, you have to pull back and ask yourself if this is the way you want to approach this field.

Jessica Honard

What kind of support system was in place at your school or were you more or less on your own?

JH: The administration did what they could to support the teachers. But it was a very large school and they were hampered by their own demands. I did have a few teachers who I could confide in. They weren't introverts necessarily, but they understood that when I needed to take five or ten minutes in the teachers lounge to recuperate, they would watch my class. During passing period, we were required to stay in the halls and have a presence. Sometimes a colleague would cover my post if I needed the quiet of the classroom for a few minutes. Also, I taught an advanced placement class and students would be at my door before school started, which was usually my time to focus and center myself, just get ready for the day. So those teachers I was able to confide in would hold them off for a few minutes.

During passing period, we were required to stay in the halls and have a presence. Sometimes a colleague would cover my post if I needed the quiet of the classroom for a few minutes. Also, I taught an advanced placement class and students would be at my door before school started, which was usually my time to focus and center myself, just get ready for the day. So those teachers I was able to confide in would hold them off for a few minutes.

You just mentioned the constant meetings and demands on your time outside of the actual classroom, which is a challenge you address in the book. You recommend that educators don't "overcommit." But isn't there a huge expectation for teachers - newer ones especially - to take part in everything at school, including all the social activities?

JH: Definitely, but some of it is probably self-imposed, especially with those new teachers. When I started teaching I wanted to put on a good appearance. I wanted to fit in because I was so young and needed the support from the people around me. So I put myself out there, which worked for a little while but then quickly became too much.

So I put myself out there, which worked for a little while but then quickly became too much.

When committing to activities outside of the classroom, introverted teachers should be aware of their own limits. It's not that they should never commit, but they should try to do so in a way that feels right to them. For example, I ran the Creative Writing Club at my school. This allowed me to be a part of extracurriculars, but it was a very different experience than, say, chaperoning the football games. It was more suited to my individual needs.

As an introvert, however, I was taught to teach as an extrovert. It's not just the fact that I would have to do a Iot of group activities or that I would feel as though I couldn't give my students time to work individually. In doing that, I had to be "on" all the time and I had to present a kind of social persona that related to that teaching stye.

Educators want more time to collaborate with colleagues. If those opportunities become yet another expectation, however, could they be perceived as another hill to climb for the more introverted teacher?

JH: I do think collaboration is essential for teachers. Just as you would want your students to collaborate, it has to be a structured collaboration, however. There were plenty of meetings I sat in on that were not, quite frankly, that advantageous to me as a teacher. But others were very helpful and I communicated positively with the other teachers. So I think that collaboration was essential to me becoming a better teacher and to us becoming a better department. But constant collaboration and the need to be constantly social just for the sake of appearences or for the sake of checking things off on a list is not necessarily helpful in the long run.

Just as you would want your students to collaborate, it has to be a structured collaboration, however. There were plenty of meetings I sat in on that were not, quite frankly, that advantageous to me as a teacher. But others were very helpful and I communicated positively with the other teachers. So I think that collaboration was essential to me becoming a better teacher and to us becoming a better department. But constant collaboration and the need to be constantly social just for the sake of appearences or for the sake of checking things off on a list is not necessarily helpful in the long run.

In the book, you provide a list of proactive steps introverted educators can take help alleviate daily pressures, including finding some sort of sanctuary or quiet space. You actually created a reading nook in your classroom where you could decompress.

JH: Well, I was lucky in that I kept the same classroom for all five years so I didn't have to move my stuff. I knew my classroom space really well and I knew how to use it to best serve my students and serve myself. But many teachers never have a permanent classroom, so it's up to each educator to try to figure out what works for them. I've spoken with teachers whose sanctuary was just their car. They would just go to the parking lot and sit in their car for five minutes. That was what they needed to just be alone for a couple of minutes. So it doesn't have to be anything fancy. I went all out because, as an English teacher, there was a reason to have a bunch of books on the shelves and places for my students to sit and read. But it served a dual purpose in helping me out as well.

I knew my classroom space really well and I knew how to use it to best serve my students and serve myself. But many teachers never have a permanent classroom, so it's up to each educator to try to figure out what works for them. I've spoken with teachers whose sanctuary was just their car. They would just go to the parking lot and sit in their car for five minutes. That was what they needed to just be alone for a couple of minutes. So it doesn't have to be anything fancy. I went all out because, as an English teacher, there was a reason to have a bunch of books on the shelves and places for my students to sit and read. But it served a dual purpose in helping me out as well.

We could be depleting the talent pool if introverts resist entering a profession generally perceived to be a better fit for extroverts. What would you say to someone who is interested in teaching but suspects that their introverted nature will prevent them from being successful?

JH: Most teachers are extroverts because I think the field naturally draws on that kind of personality. It's important to recognize and understand, however, that the idea that you can't be a good teacher and an introvert is completely false. They should know that the fact they are introverted doesn't mean they can't do anything that any other teacher can do. Introverts can be amazing teachers. They can be really passionate about reaching their students. It's just important to figure out from the beginning what boundaries to set for themselves and to enforce those boundaries to the best of their ability.

It's important to recognize and understand, however, that the idea that you can't be a good teacher and an introvert is completely false. They should know that the fact they are introverted doesn't mean they can't do anything that any other teacher can do. Introverts can be amazing teachers. They can be really passionate about reaching their students. It's just important to figure out from the beginning what boundaries to set for themselves and to enforce those boundaries to the best of their ability.

We need introverted teachers because they can be advocates and cheerleaders for the introverted students. It's two sides of the same coin. They can reach those students, bring them onboard and give them the space that they need. And the introverted teachers need to feel as though they can own their own nature and their own temperament, be OK with it, and not feel as though that makes them less of a good teacher.

The psychologist listed the symptoms of emotional burnout

11:48 Sep. 24, 2020 2475 0

24, 2020 2475 0

Maxim Blinov/RIA Novosti

The problem affects both high and low positions.

Psychologist Maria Rybnikova spoke about the symptoms of this disease on the air of the radio station "Moscow speaking".

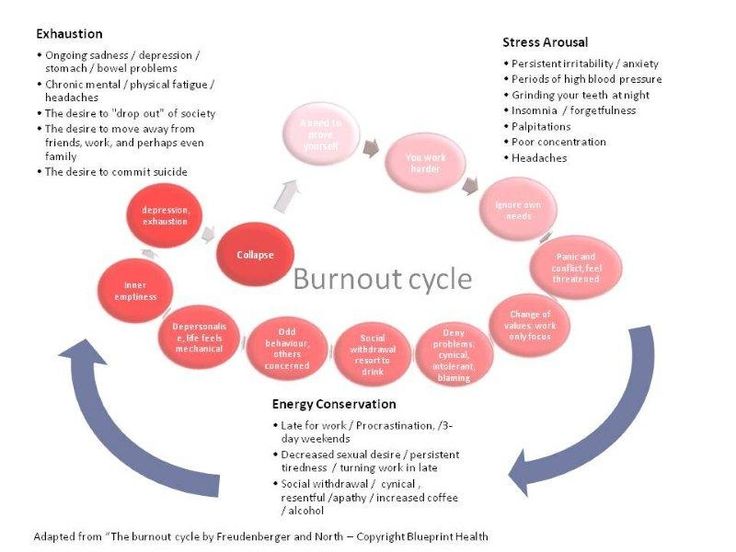

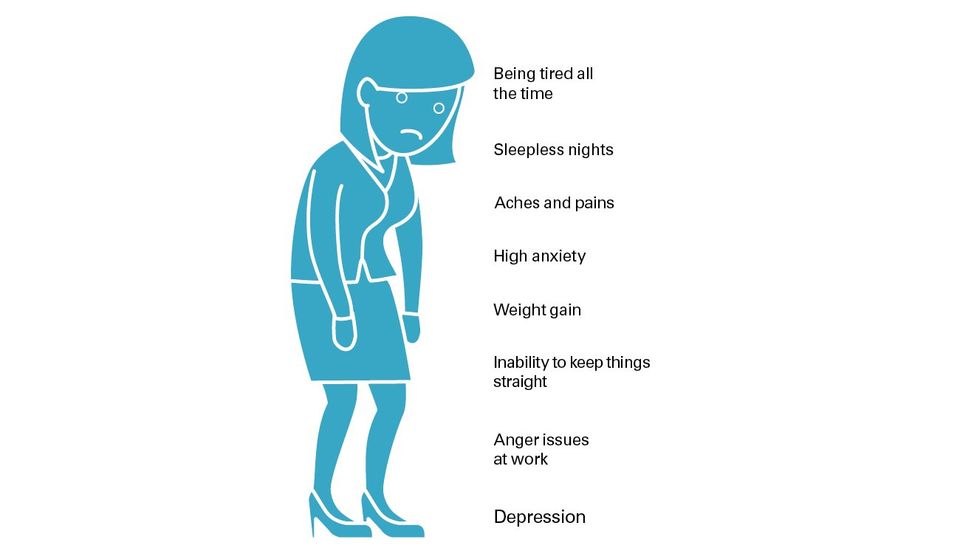

“There are five kinds of symptoms. The first is physical, when you get up and are tired, and you may have dizziness, insomnia. Weakness, nausea, even shortness of breath happens. There are also emotional symptoms, when there is a lack of emotional manifestation, that is, when there is some good news, and the person reacts like this: “well, yes, class.” Or vice versa. For example, if a pedestrian crosses slowly, you are sitting in a car, then, accordingly, aggression can go to this pedestrian. This is also a sign of emotional burnout. Next comes the behavioral when, for example, you come home from work and start eating a lot. Another important symptom is intellectual, when a person always wants to learn something new, and after a certain period of time you look at this person, but he is not interested in anything.

The fifth symptom is social. This is when a person simply isolates himself from people, or he says that no one is helping him. nine0003

Rybnikova added that emotional burnout can be prevented.

“The first thing to determine is whether you are an extrovert or an introvert. You need to understand for yourself: what type you are and where you can best come in handy. The second important factor is passing the career guidance test. You must determine your type, your temperament."

Last year, burnout was included in the International Classification of Diseases. According to the HR company Hays, 53% of workers in Russia have experienced this problem personally. nine0003

Printable version

All news

-

13:49 Oct. 20, 2022 2496

The psychologist spoke about the possible causes of laziness

-

16:49 March 20, 2022 2052

Medical psychologist named five signs of psychosomatic diseases

-

14:00 Jan.

7, 2022 1684

7, 2022 1684 In Belgium, it was forbidden to disturb civil servants after hours

-

06:50 Dec. 16, 2021 1159

Poll: 75% of Russians reported emotional burnout

-

13:05 April 19, 2021 3485

The psychologist told which professions are threatened with burnout at work

-

06:44 April 19, 2021 2334

Survey: 23% of professionals reported being in the process of professional burnout

-

12:23 Dec. 22, 2020 2325

The teachers' union did not see an opportunity to help teachers cope with burnout

-

07:31 Sep. 29, 2020 1815

A cardiologist called positive emotions the prevention of heart disease

-

10:57 Sep. 24, 2020 10117

Pulmonologist called the first signs of lung damage

-

10:29 July 26, 2020 158084

The Department of Health of Moscow told how to distinguish the flu from the coronavirus

-

14:16 July 18, 2020 20831

Virologist explained the origin of the rash in coronavirus

-

12:50 May 3, 2020 4827

Doctor Evgeny Komarovsky described the algorithm of actions for symptoms of coronavirus

-

15:42 April 19, 2020 6607

The doctor declared the danger of a disease that develops a precancerous condition of the stomach

-

09:45 Feb.

9, 2020 13368

9, 2020 13368 The chief endocrinologist of Moscow called the first signs of diabetes in children

-

18:41 Jan. 26, 2020 75322

Gastroenterologist named non-obvious symptoms of dangerous diseases

-

11:54 July 13, 2019 4850

Doctors determined the norm of healthy sleep

Communication with the air

Teacher burnout: how to understand what's wrong with you. And how to avoid

Professional burnout of teachers has been talked about more and more lately. But teachers who are faced with this problem do not always know how to deal with it. Participants of the "Teacher of the Future" competition of the "Russia - Land of Opportunity" platform share their stories and tell how to keep their strength and spirit for the entire academic year. nine0003

The requirements for a teacher are constantly growing: if earlier it was enough to know your subject, be able to convey knowledge to students and have high moral qualities, now the list has expanded significantly. The teacher must, in addition to the above, also be self-confident, active, freely navigate digital technologies and use them in their practice, competently balance between teaching work, reporting to management and personal life, while maintaining a positive attitude, improve their skills and be in keep abreast of the latest trends in teaching practice. In short, the modern teacher must be successful. What most often prevents a teacher from meeting the current requirements of society? nine0003

The teacher must, in addition to the above, also be self-confident, active, freely navigate digital technologies and use them in their practice, competently balance between teaching work, reporting to management and personal life, while maintaining a positive attitude, improve their skills and be in keep abreast of the latest trends in teaching practice. In short, the modern teacher must be successful. What most often prevents a teacher from meeting the current requirements of society? nine0003

What is professional burnout

The work of a teacher belongs to the “person-to-person” system: it requires high involvement and dedication. At a certain moment, the internal resource of the teacher is exhausted: it is not enough not only for work, but also for a normal personal life. Emotional burnout occurs.

Burnout is the body's reaction to continuous stress caused by problems at work

It is characterized by emotional exhaustion, disappointment, indifference to everything. Psychologists note that professional burnout is associated with work in a "helping" area, which is precisely the work of a teacher. nine0003

Psychologists note that professional burnout is associated with work in a "helping" area, which is precisely the work of a teacher. nine0003

Irina Pavliuk, computer science teacher, Gymnasium No. 19 named after. N. Z. Popovicheva in Lipetsk, sees two reasons for professional burnout: “I call objective the very work of a teacher involves only horizontal development, while in other professions there is both horizontal and vertical development. To subjective reasons, I include the living conditions of a particular person : where and how he lives, what kind of people surround him, what kind of students, and so on.

The lack of an incentive for professional development, which is usually career growth in other areas, is fully compensated by the external environment - constantly changing working conditions, new textbooks, methods and teaching aids. However, they also create additional stress.

“Your perception of information has been developed over the years. And the methods of its transmission developed over the years. But the children are different every time, and every time you have to readjust, change your own views,” explains Elena Lysenko, mathematics teacher at Gymnasium No. 21 in Kemerovo. nine0003

And the methods of its transmission developed over the years. But the children are different every time, and every time you have to readjust, change your own views,” explains Elena Lysenko, mathematics teacher at Gymnasium No. 21 in Kemerovo. nine0003

Among the factors that hinder development, teachers name routine work, a large number of reports and additional events. Elena Belova, teacher of Russian language and literature, director of lyceum No. 22 in Belovo, Kemerovo region, sees another reason for the teacher’s loss of interest in work is the change in the image of the profession: “Those teachers who go through emotional burnout came to school more than a dozen years ago . Often they chose this job not only because of their profession, but also because of the social status of the teacher - they respected him unconditionally, bowed before him. Most of today's children do not have authorities, and such a discrepancy can drive a teacher into despondency. nine0003

At the same time, amazing opportunities open up before the modern teacher. But in order to use them, the teacher needs to really change his attitude towards the profession, learn flexibility and start using the latest tools for both planning and interaction with students.

But in order to use them, the teacher needs to really change his attitude towards the profession, learn flexibility and start using the latest tools for both planning and interaction with students.

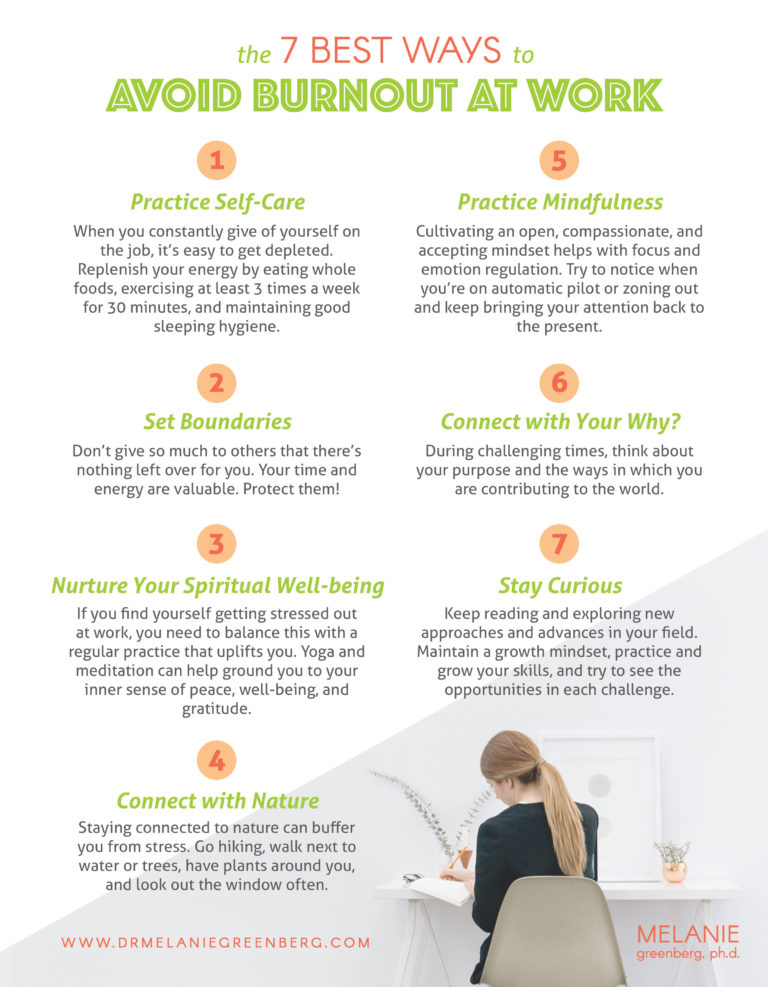

How to avoid burnout

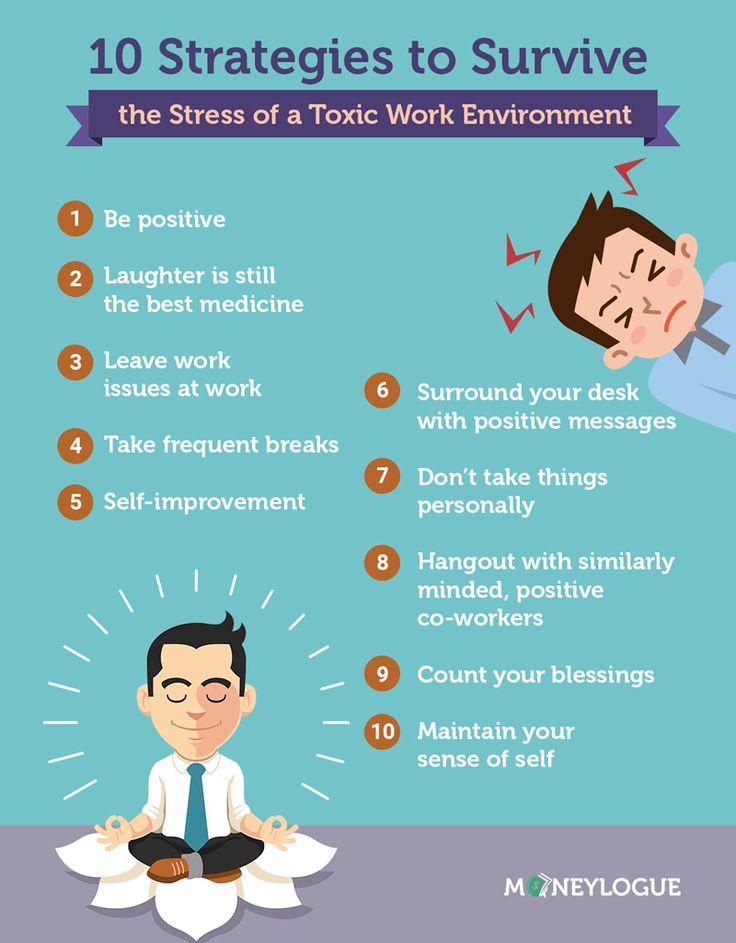

Participants of the “Teacher of the Future” competition gave some advice based on their own experience on how to prevent professional burnout, cope with it and find resources for a new inspiring round in work:

1. Clearly plan and prioritize work

It is not uncommon for young teachers to devote themselves entirely to their work, spending their personal time preparing for lessons, checking homework, or participating in school life. As a result, this imbalance does not lead to anything good. Elena Lysenko is sure: “Reasonable comprehension, control of emotions, clear planning of the day, correct prioritization, alternation of work and rest - these are my tips. If you feel that you are losing interest in work, increase your personal time: for sports, travel, communication with friends. nine0003

nine0003

2. Communicate with colleagues, participate in school life and external activities

Obsessing about work and hiding from colleagues are obviously wrong steps. The place where a person spends most of the day should be comfortable and interesting for him. Elena Belova says, for example, that a physical education teacher at their school conducts free fitness for teachers: “Health is very important. We have an active life at school. We ourselves hold "Library Night", which does not depend on the All-Russian. Children, teachers, and parents are involved here. The school has its own territory of 2 hectares. We ennoble it ourselves and are proud of it.” Elena Belova, both as a teacher and as a director, believes that school initiatives should come not only from above, but also from the students and teachers themselves, then the mood will be optimistic. nine0003

Colleagues offered Irina Pavlyuk to take part in the "Teacher of the Future" competition, she agreed for the company. The director agreed. And in the end, she got an unexpected result for herself: “Participation in the competition is a good step to shake things up. It has become psychologically easier for me to relate to work, I perceive everything more easily thanks to the experience and skills gained during the competition.”

The director agreed. And in the end, she got an unexpected result for herself: “Participation in the competition is a good step to shake things up. It has become psychologically easier for me to relate to work, I perceive everything more easily thanks to the experience and skills gained during the competition.”

3. Get the right attitude

Almost every teacher has experienced professional burnout. There is fatigue, apathy, and a desire to change the type of activity, and even to radically change something in life. “I really love my job, I love children. They don’t succeed the first time, but no matter how hard it is for them, they try. And I am with them. Of course, it can be difficult, sometimes you don’t even see a way out. I think you need to change your attitude to the situation. And to believe that the most interesting is yet to come,” shared Elena Lysenko. nine0003

The professional competition "Teacher of the Future" of the "Russia - Land of Opportunity" platform is a project to support and promote teachers who are able and ready to work together.