Atypical antipsychotic examples

Atypical antipsychotics: Uses, side effects, examples

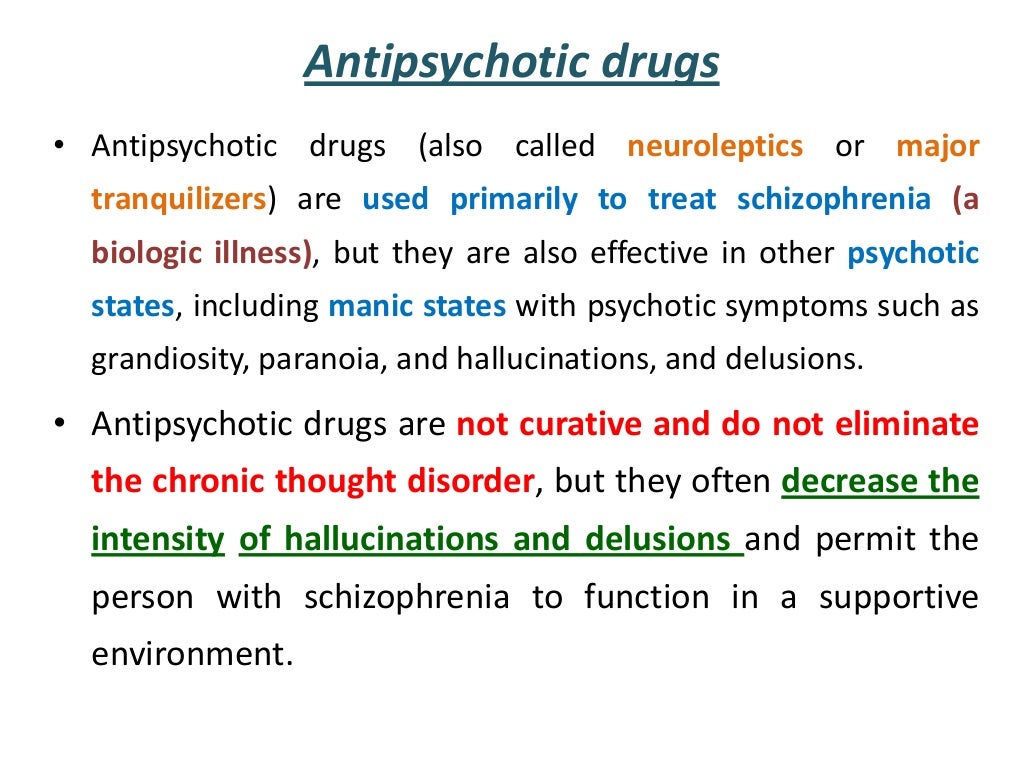

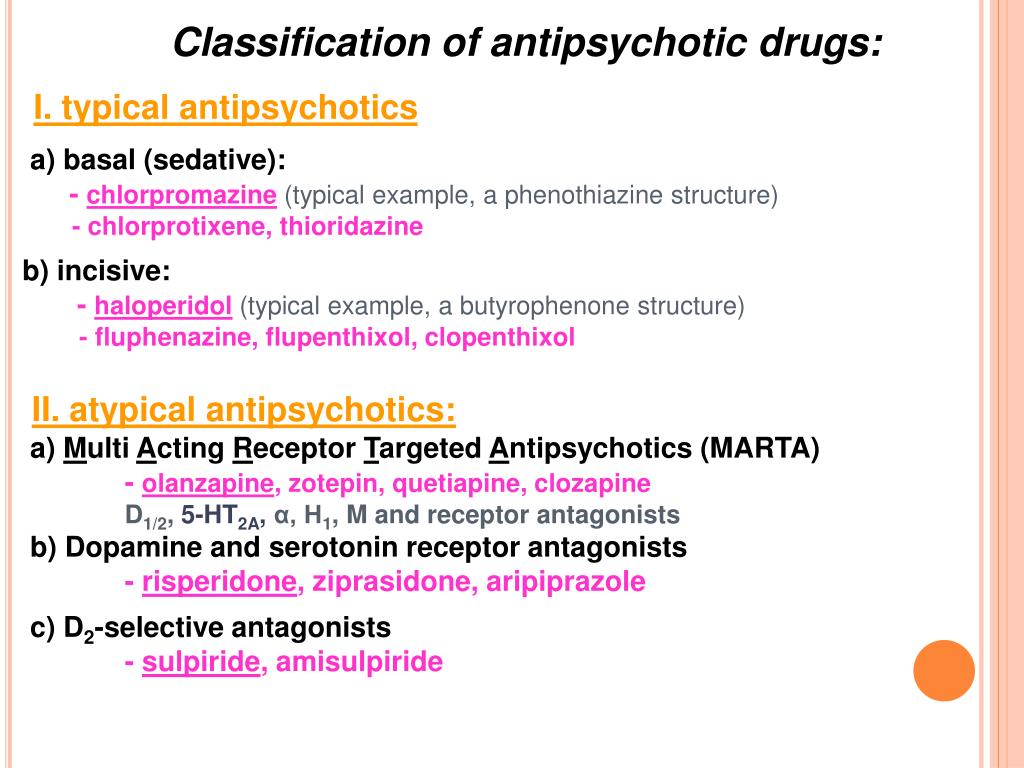

There are two types of antipsychotic drugs: typical and atypical. Atypical antipsychotics usually have fewer and less severe side effects, so doctors often prescribe them over typical antipsychotics.

Doctors prescribe atypical antipsychotics to treat a range of mental health conditions, including schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and treatment-resistant mania. They may also prescribe atypical antipsychotics off-label for other conditions, such as Tourette’s syndrome.

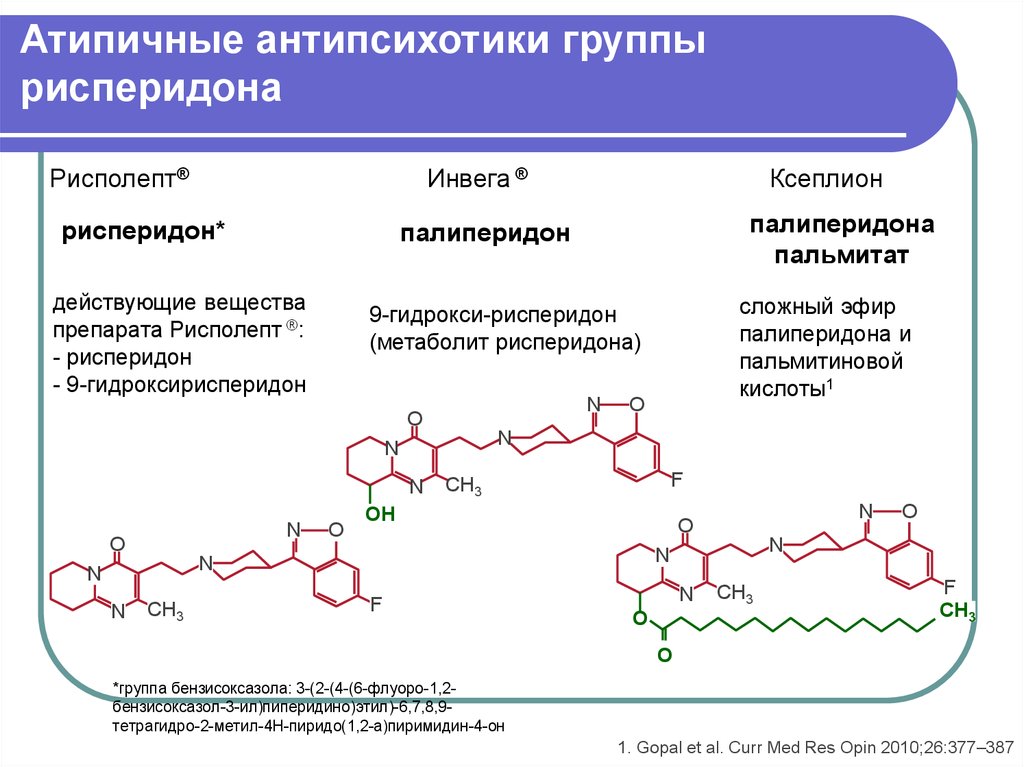

One example of a typical antipsychotic drug is prochlorperazine (Procomp). An example of an atypical antipsychotic drug is risperidone (Risperdal).

Keep reading to learn about the differences between typical and atypical antipsychotics, their uses, side effects, and more.

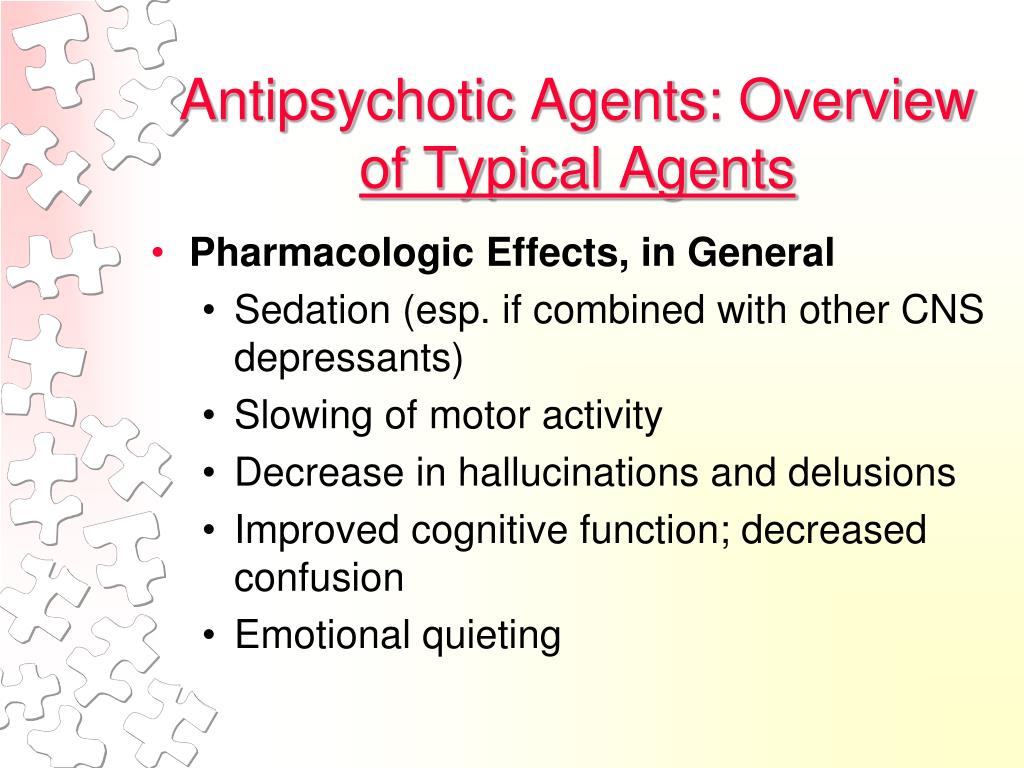

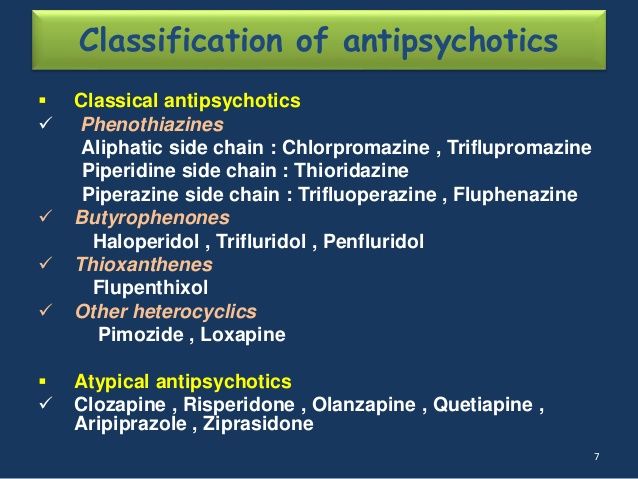

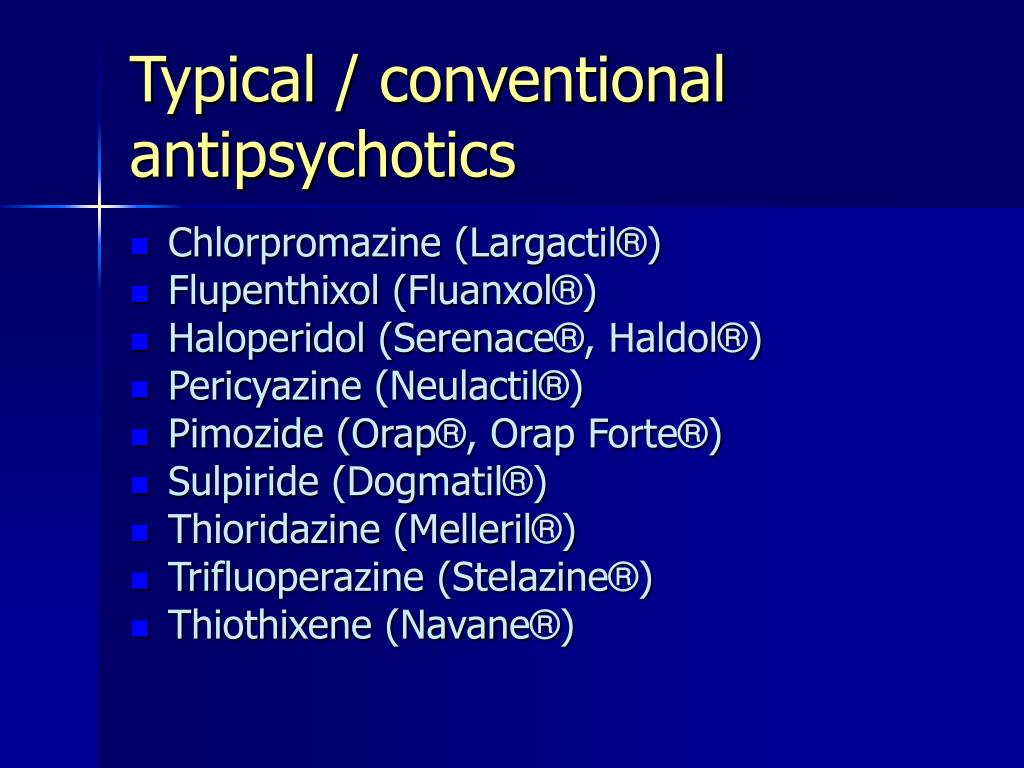

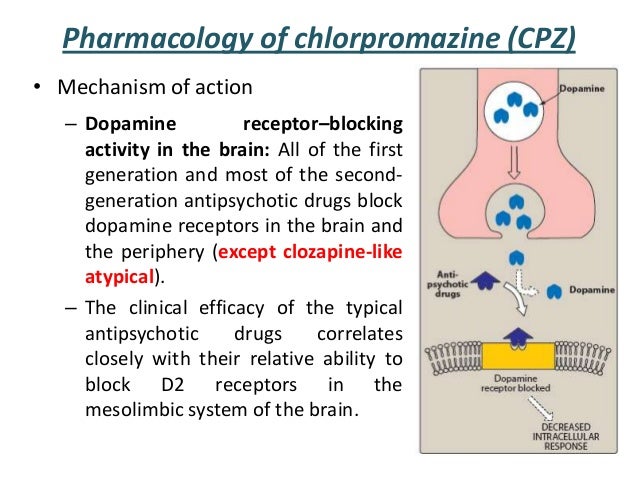

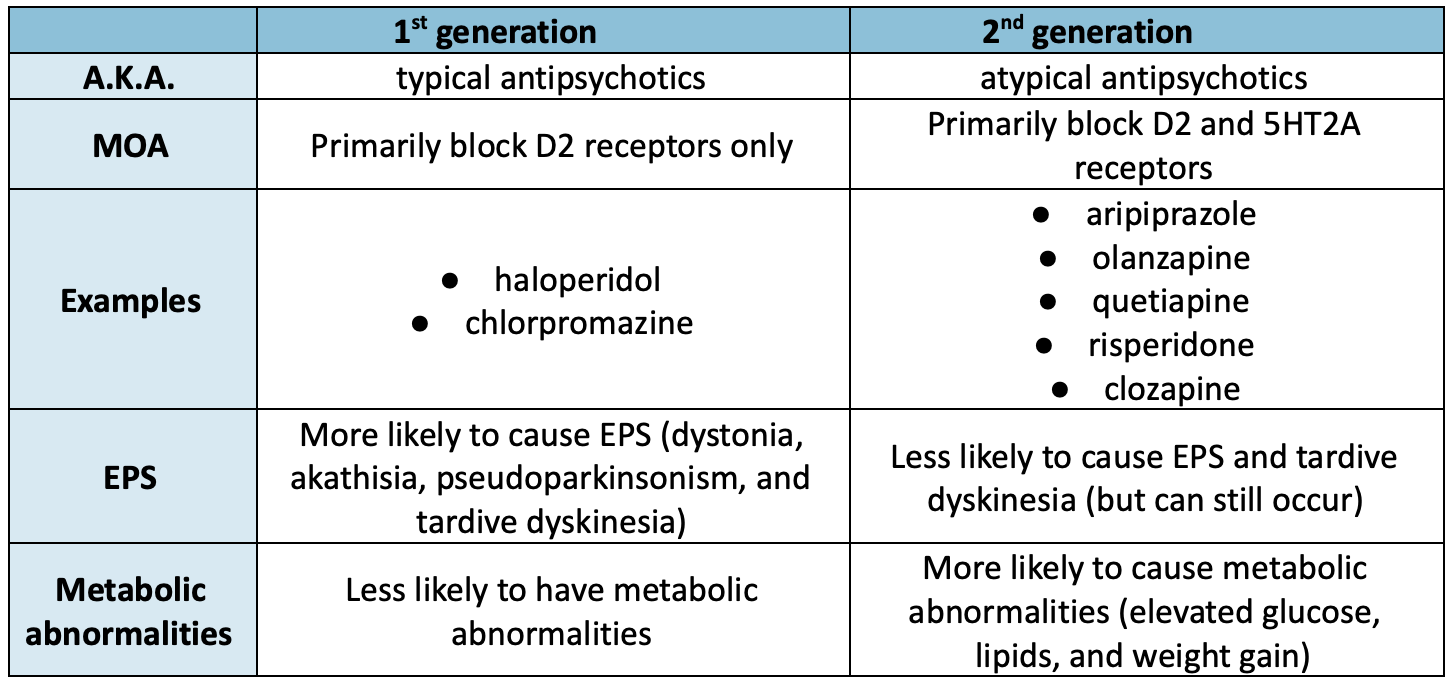

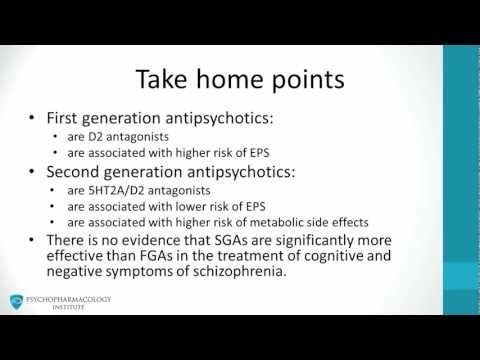

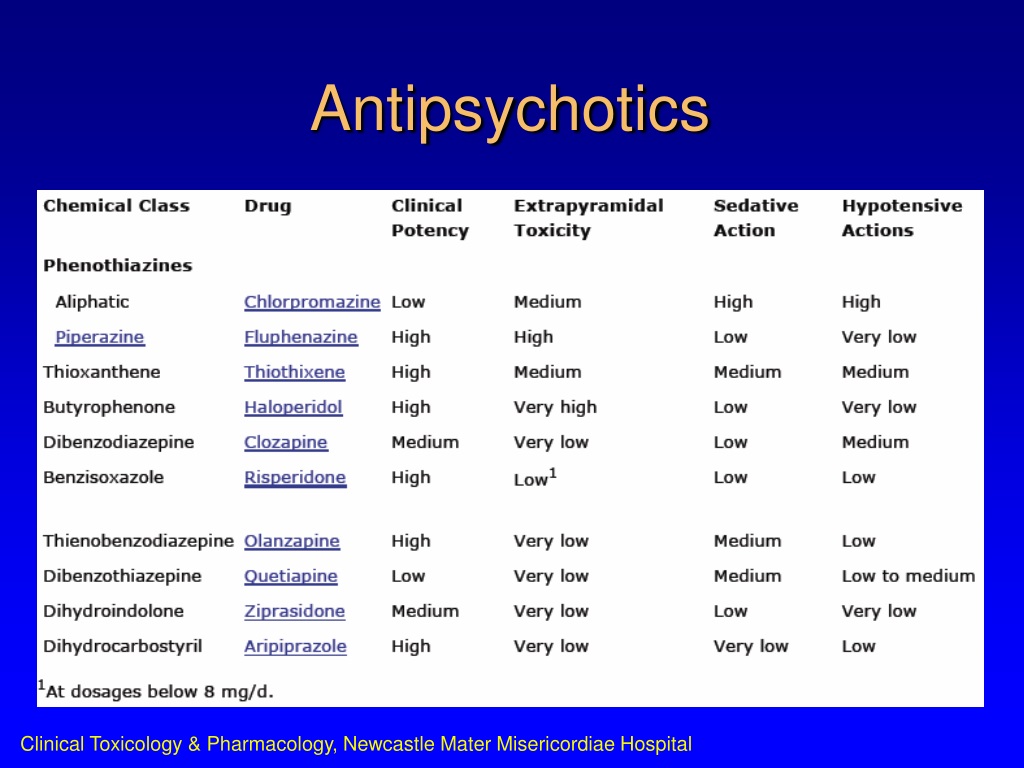

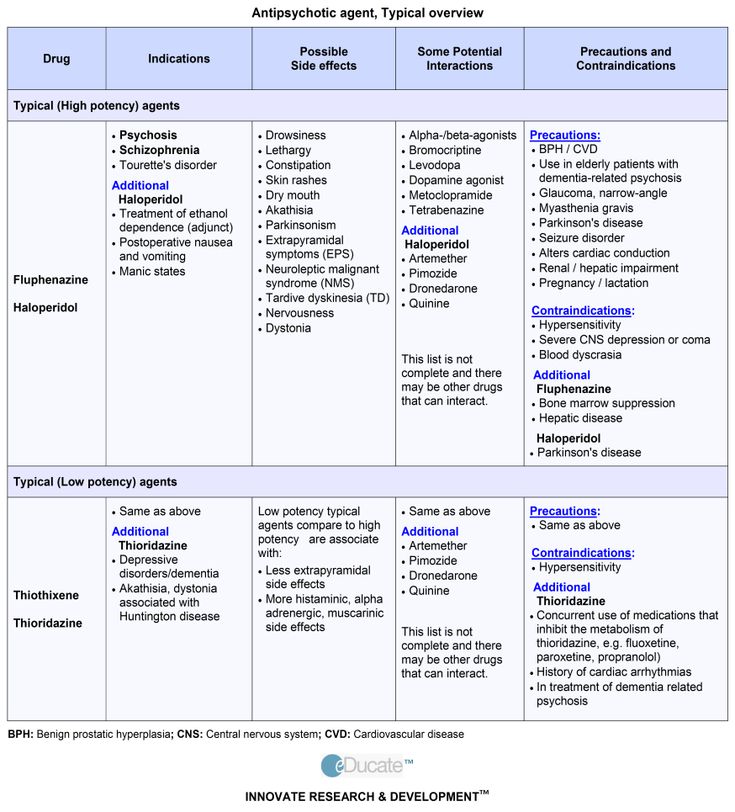

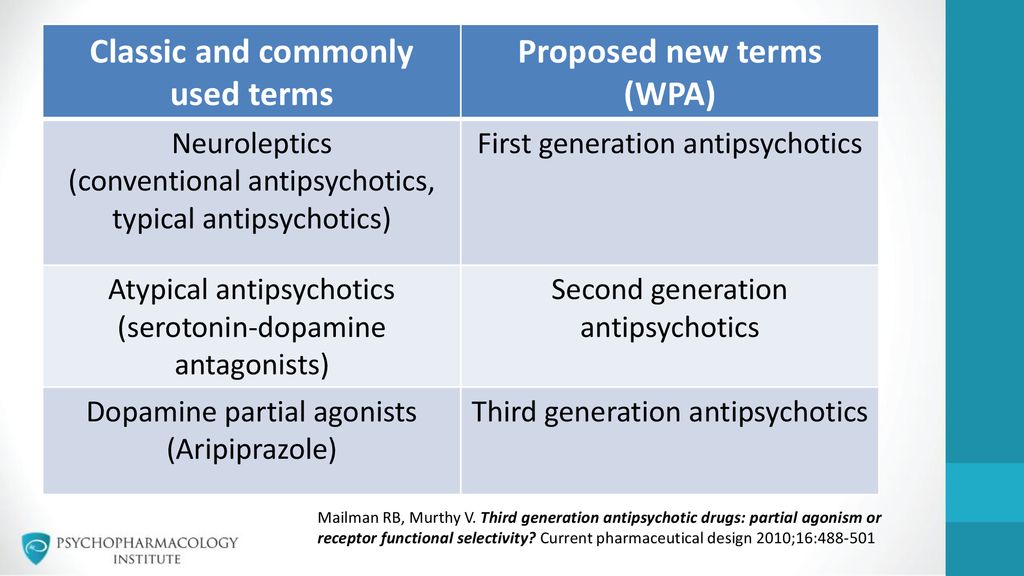

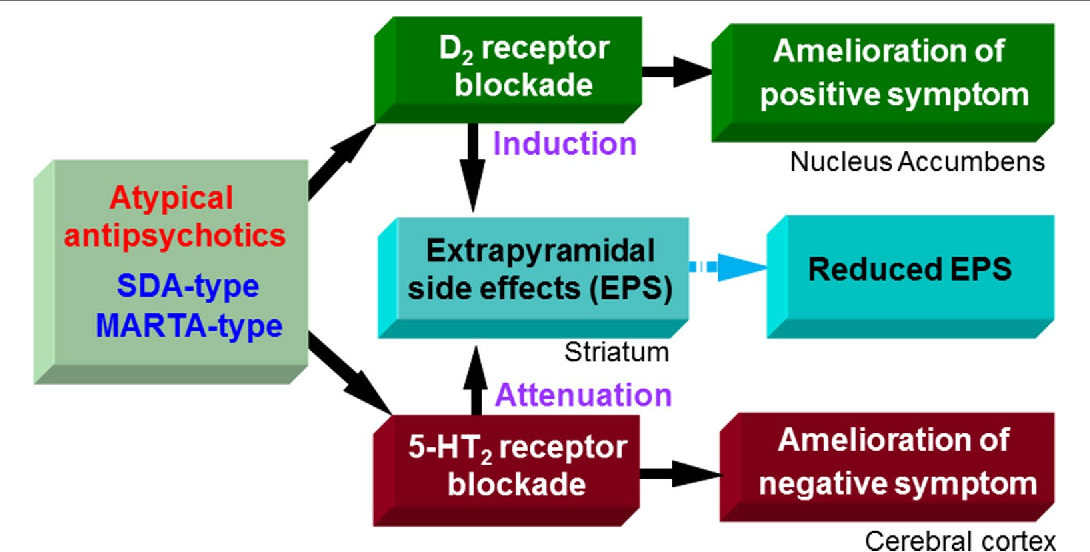

Typical antipsychotics were the first in their drug class and are sometimes called first-generation antipsychotics. They act on dopamine receptors in the brain.

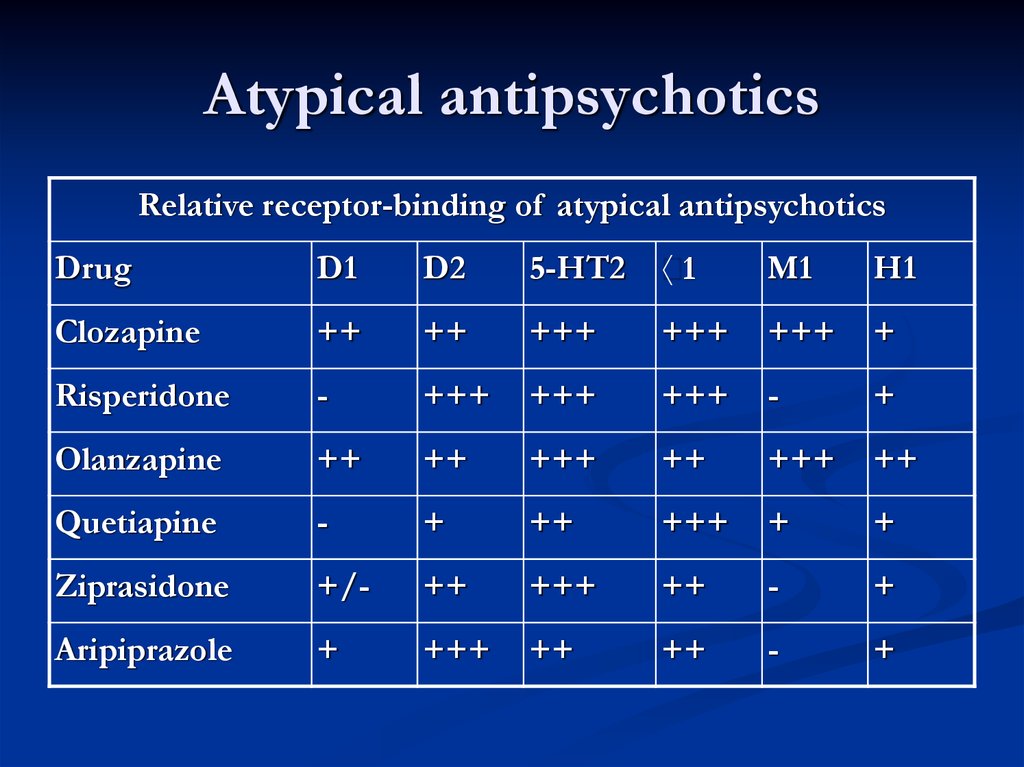

Drug manufacturers later developed second-generation antipsychotics, which are also called atypical antipsychotics. They act on both dopamine and serotonin receptors.

Atypical antipsychotics also have some antidepressant effects when used alone or with an antidepressant.

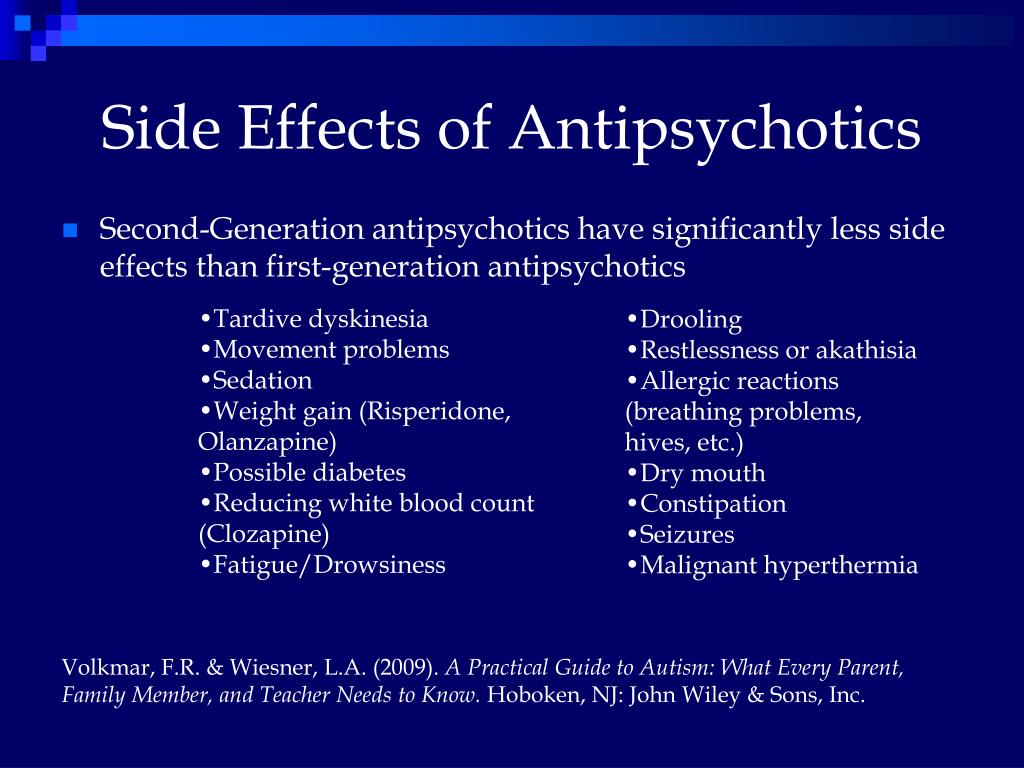

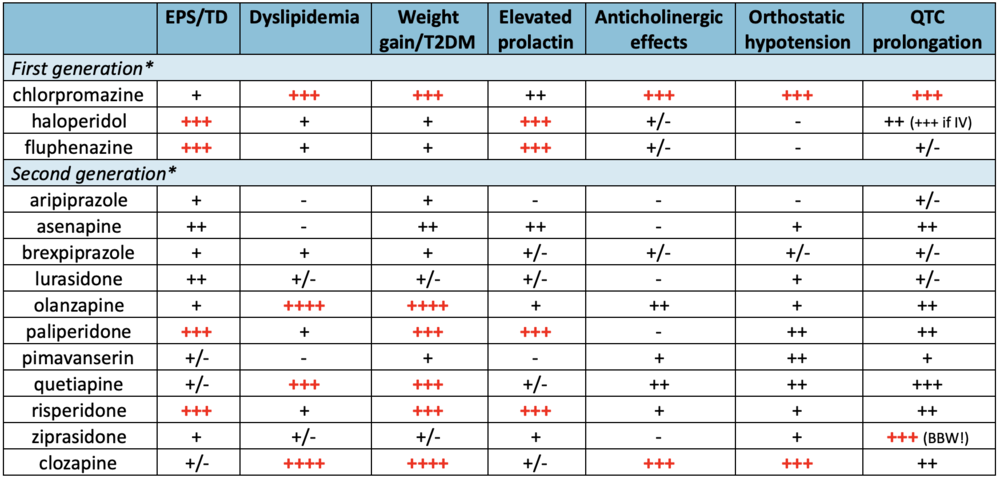

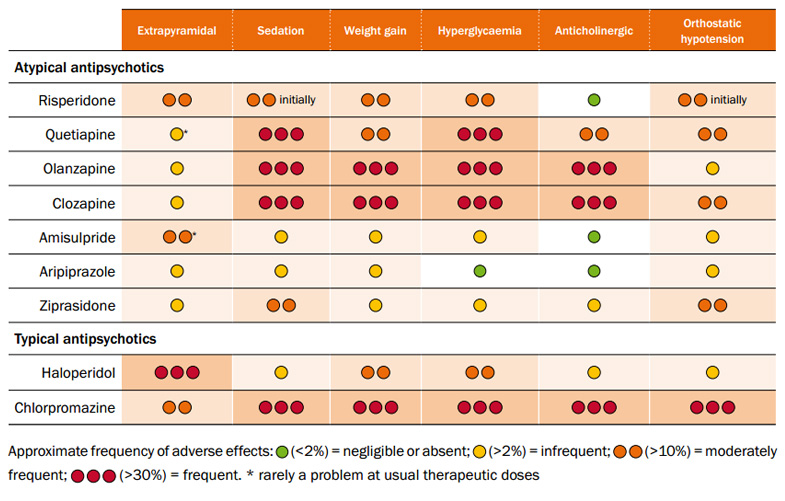

The main advantage of atypical antipsychotics is that they have fewer and less severe side effects than typical antipsychotics.

The most significant difference between typical and atypical antipsychotics is their side effects.

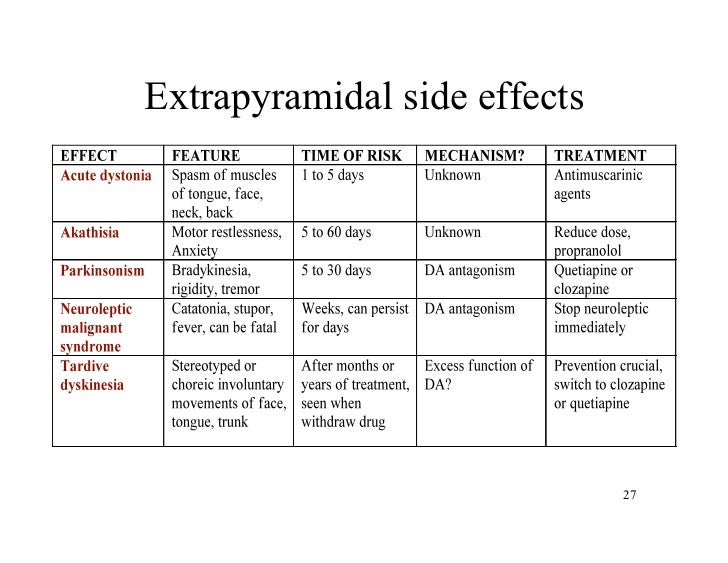

Typical antipsychotics have significant extrapyramidal symptoms. These are drug-induced movement disorders. They may include:

- Dystonia: uncontrolled muscle contractions that cause repetitive movements and abnormal posture

- Akathisia: a state of restlessness

- Parkinsonism: a disorder causing tremors, slow movements, and rigidity

- Tardive dyskinesia: a chronic condition causing repetitive muscle movements in the face, neck, arms, and legs

- Tardive akathisia: a delayed start of akathisia after starting an antipsychotic drug

Extrapyramidal symptoms can be debilitating. Some people report the symptoms interfere with activities of daily living, social functioning, and speaking.

Some people report the symptoms interfere with activities of daily living, social functioning, and speaking.

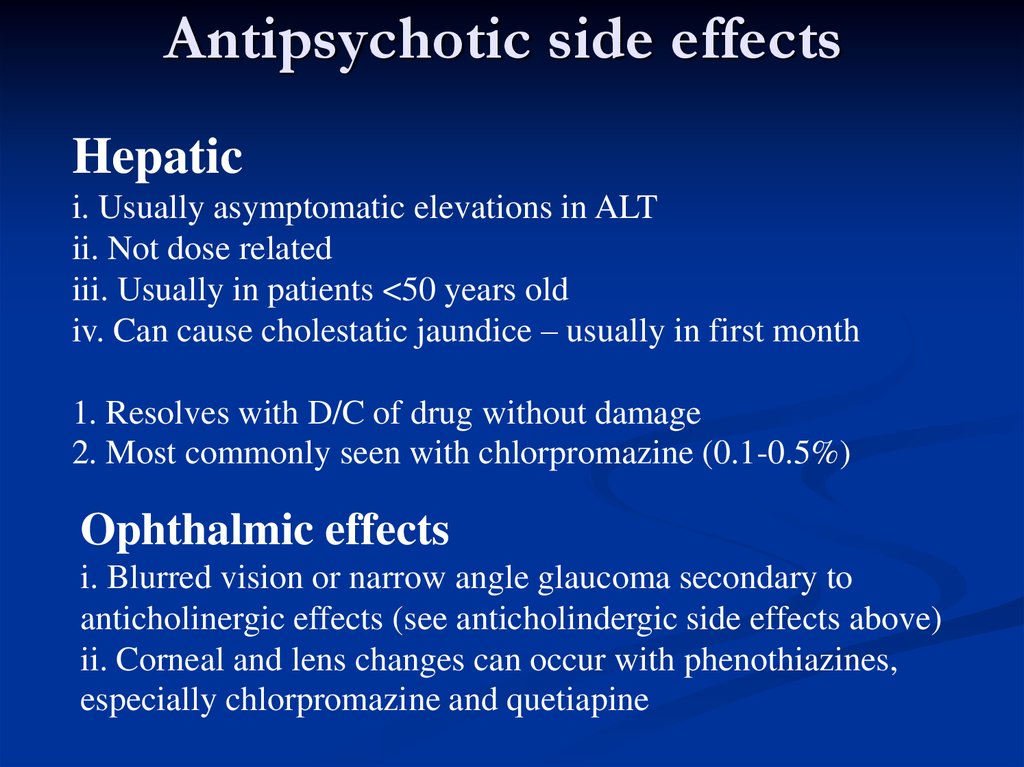

Other possible side effects of antipsychotics include:

- dry mouth

- constipation

- urinary retention

- allergic reactions

Severe side effects of antipsychotics may affect heart function.

Because antipsychotics act on dopamine receptors, they may increase a person’s level of prolactin. This is a hormone released in the pituitary gland.

High prolactin levels in the blood can cause:

- abnormal breast milk production

- breast enlargement

- loss of menstrual periods

- impotence in males

- loss of orgasm in females

A note about sex and gender

Sex and gender exist on spectrums. This article will use the terms “male,” “female,” or both to refer to sex assigned at birth. Click here to learn more.

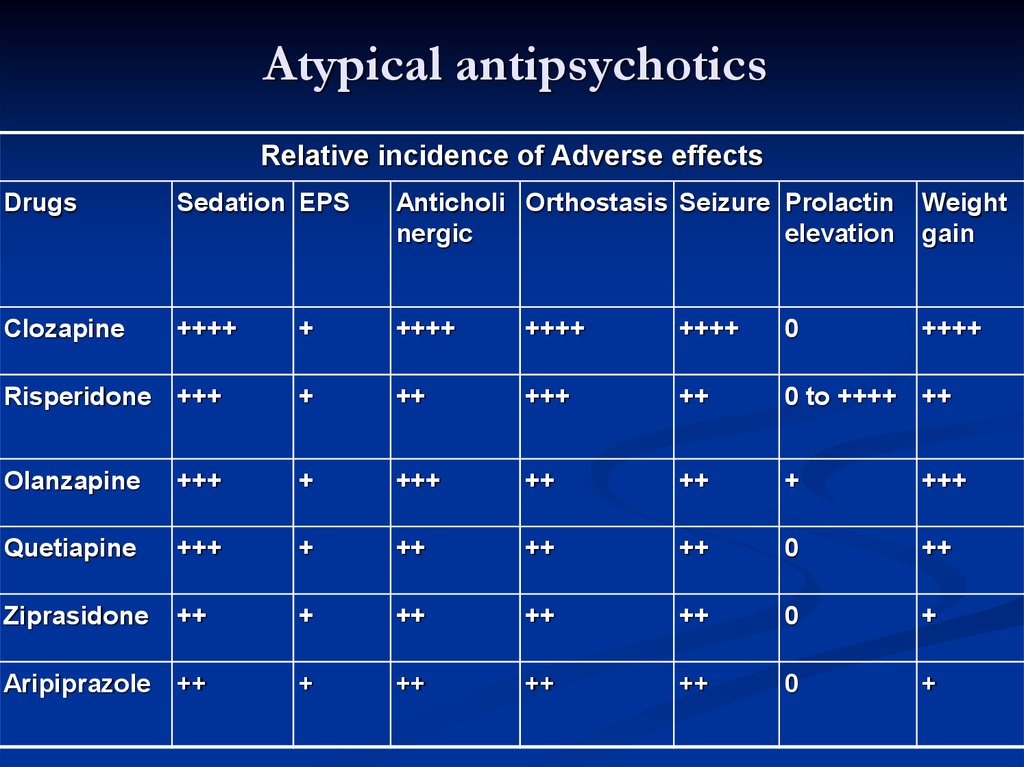

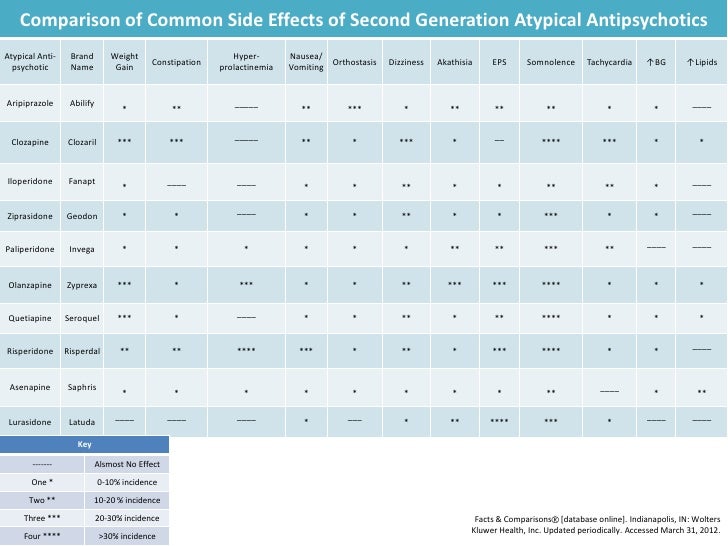

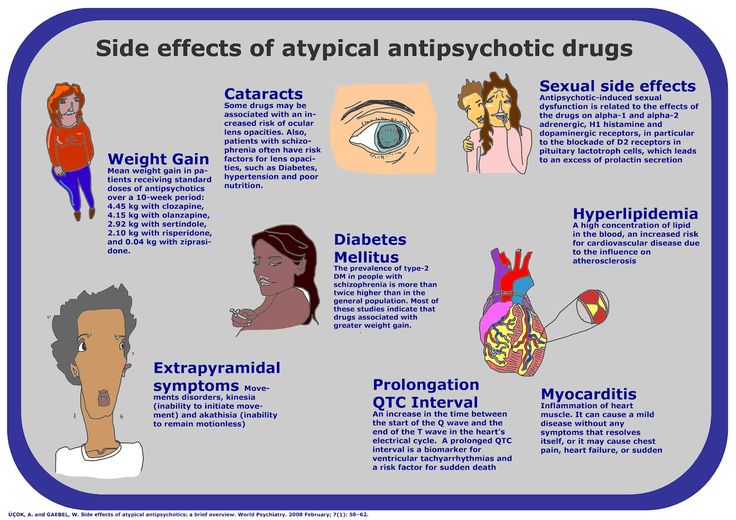

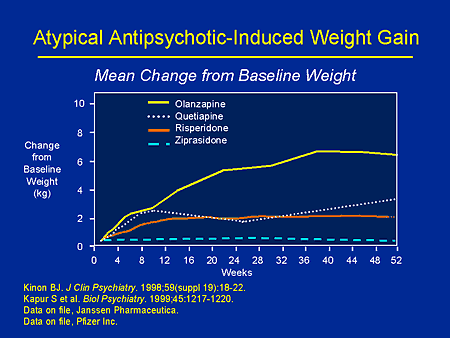

Although atypical antipsychotics have less significant side effects, they can cause:

- weight gain

- high cholesterol

- diabetes

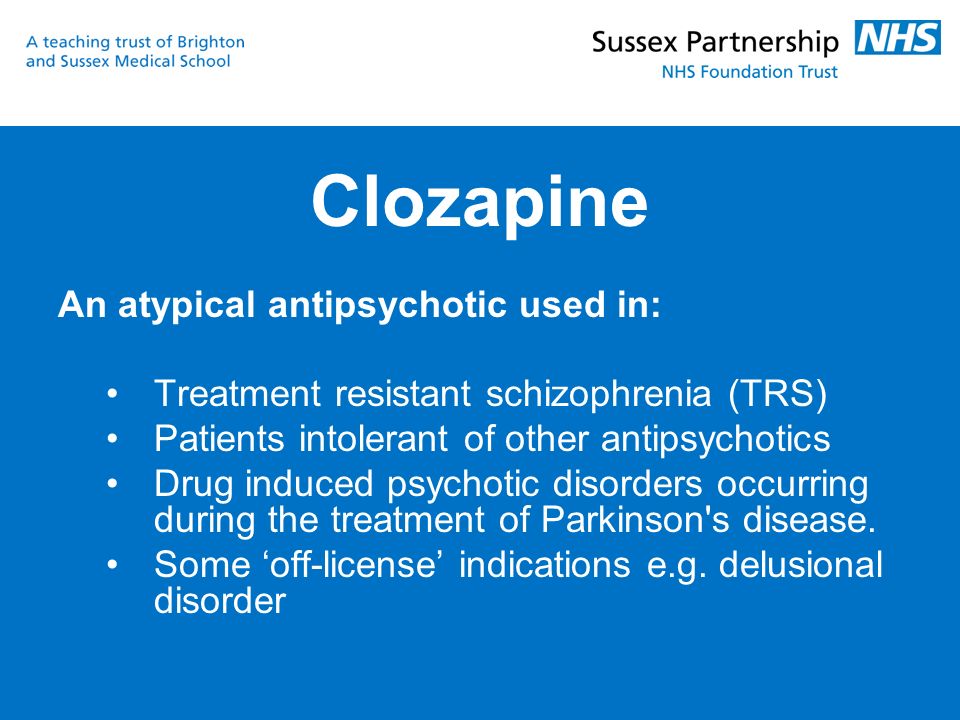

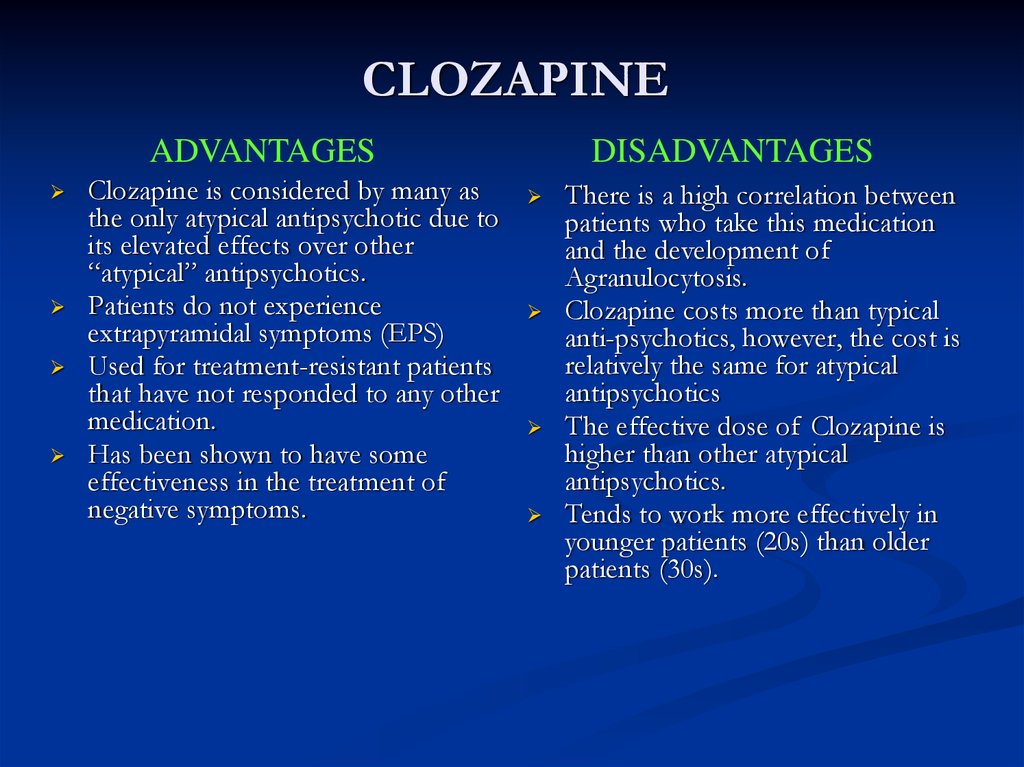

One atypical antipsychotic called clozapine carries a risk of myocarditis, which is inflammation of the heart muscle. However, the risk of dying from myocarditis from taking clozapine is low.

However, the risk of dying from myocarditis from taking clozapine is low.

Antipsychotics have a boxed warning issued by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This is the most severe warning for a drug.

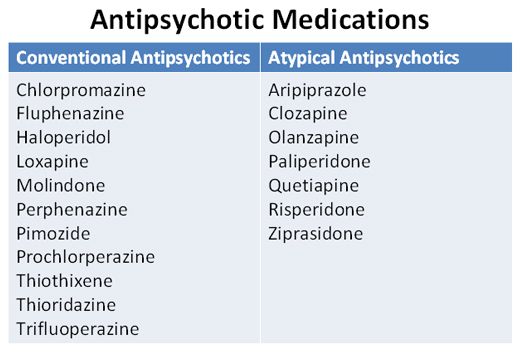

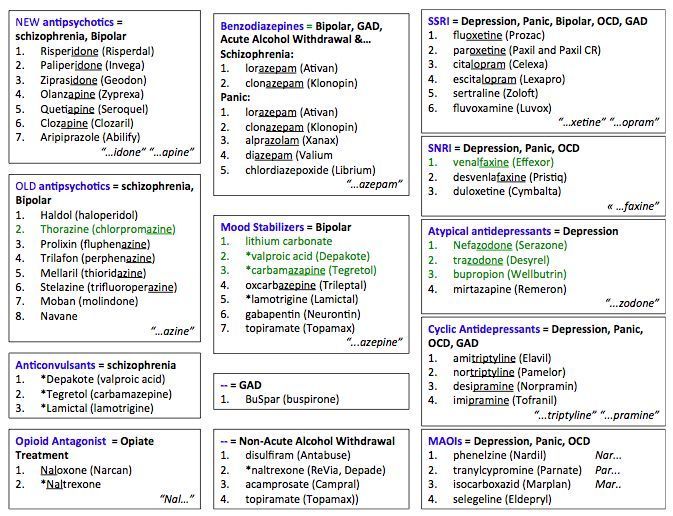

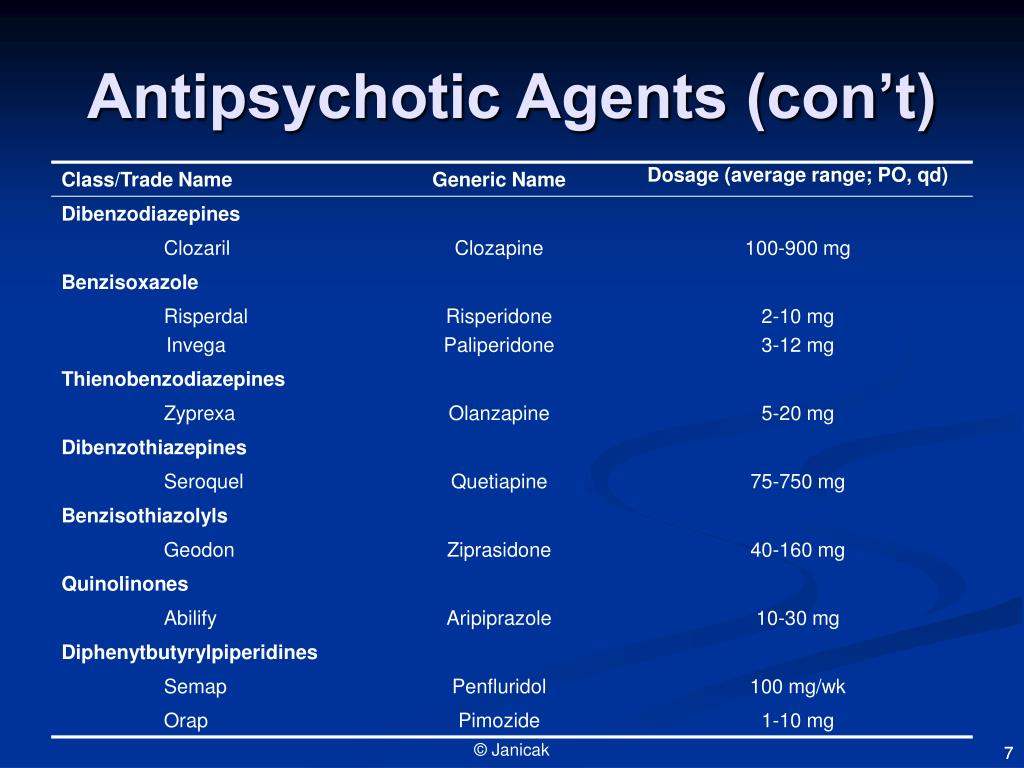

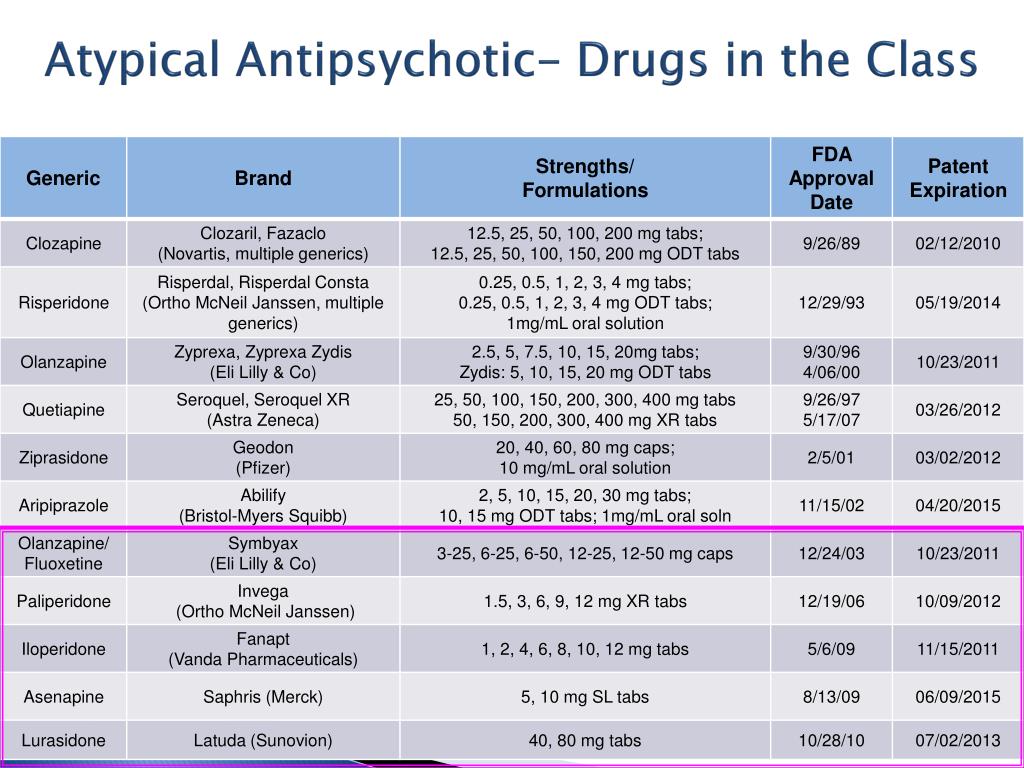

The following table lists examples of typical and atypical antipsychotics:

| Typical antipsychotics | Atypical antipsychotics |

|---|---|

| acetophenazine (Tindal) | aripiprazole (Abilify) |

| haloperidol (Haldol) | asenapine (Saphris) |

| loxapine (Adasuve) | brexpiprazole (Rexulti) |

| molindone | cariprazine (Vraylar) |

| perphenazine | clozapine (Clozaril) |

| pimozide | iloperidone (Fanapt) |

| prochlorperazine (Procomp) | lurasidone (Latuda) |

| thiothixene | olanzapine (Zyprexa) |

| trifluoperazine | paliperidone (Invega) |

| quetiapine (Seroquel) | |

| risperidone (Risperdal) | |

| ziprasidone (Geodon) |

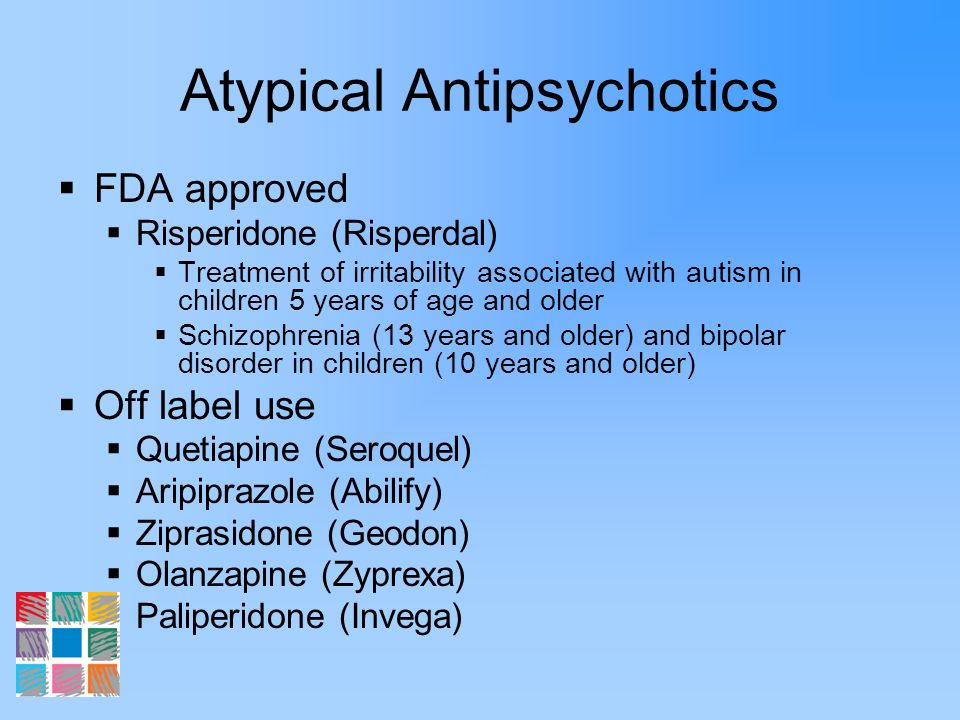

The FDA has approved antipsychotics for various psychiatric conditions.

Different types of antipsychotics and the conditions they treat are listed below:

| Typical antipsychotics | Typical or atypical antipsychotics (except clozapine) | Clozapine |

|---|---|---|

| delusional disorders | schizophrenia | childhood schizophrenia |

| Tourette’s syndrome | schizoaffective disorder | tardive dyskinesia |

| major depressive disorder (with psychotic characteristics) | treatment-resistant mania | |

| borderline personality disorder (BPD) | obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) | |

| dementia | childhood autism | |

| substance-induced psychotic disorder | Parkinson’s disease | |

| sudden manic episode | Huntington’s disease | |

| schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (with suicidal thoughts) | ||

| severe psychotic symptoms |

Sometimes, doctors may prescribe atypical antipsychotics for conditions the FDA has not approved them for. This is called off-label prescribing.

This is called off-label prescribing.

For example, atypical antipsychotics may help people with Tourette’s syndrome, but this is an off-label use.

However, doctors can sometimes incorrectly prescribe antipsychotics. A concerning practice seen in some care homes is doctors overprescribing antipsychotic medications to older adults.

Off-label uses of antipsychotics in older adults in nursing homes include dementia-related behaviors, such as aggression and agitation. Antipsychotics are not safe when prescribed inappropriately to a vulnerable group of people.

National programs in the United States have worked to reduce the unsuitable prescribing of antipsychotics in nursing homes. While researchers note a decline in this practice, more work is needed to further reduce the improper prescribing of antipsychotics in nursing homes.

When taking antipsychotic medications, people should report any side effects to a doctor. Sometimes, changing antipsychotics can help improve the medical condition while minimizing side effects.

If a person is taking atypical antipsychotics, doctors will review their body weight and order blood tests to check for increased cholesterol and blood sugar. Follow-up appointments may also include having an electrocardiogram to evaluate heart function.

For people taking clozapine, doctors will check neutrophil levels. This is a type of white blood cell that helps the body protect itself from infections. Clozapine can drop neutrophil levels and increase a person’s risk of illnesses.

Doctors can prescribe a range of types of antipsychotics. Each type has different side effects. While some health conditions require a typical antipsychotic medication, atypical antipsychotics are often preferred.

Atypical antipsychotic medications usually have fewer and less severe side effects than typical antipsychotic medications.

Weight gain, diabetes, and high cholesterol are side effects that can occur with atypical antipsychotics. When taking antipsychotics, follow-up appointments with a doctor are crucial to a person’s care.

Atypical antipsychotics: Uses, side effects, examples

There are two types of antipsychotic drugs: typical and atypical. Atypical antipsychotics usually have fewer and less severe side effects, so doctors often prescribe them over typical antipsychotics.

Doctors prescribe atypical antipsychotics to treat a range of mental health conditions, including schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and treatment-resistant mania. They may also prescribe atypical antipsychotics off-label for other conditions, such as Tourette’s syndrome.

One example of a typical antipsychotic drug is prochlorperazine (Procomp). An example of an atypical antipsychotic drug is risperidone (Risperdal).

Keep reading to learn about the differences between typical and atypical antipsychotics, their uses, side effects, and more.

Typical antipsychotics were the first in their drug class and are sometimes called first-generation antipsychotics. They act on dopamine receptors in the brain.

Drug manufacturers later developed second-generation antipsychotics, which are also called atypical antipsychotics. They act on both dopamine and serotonin receptors.

Atypical antipsychotics also have some antidepressant effects when used alone or with an antidepressant.

The main advantage of atypical antipsychotics is that they have fewer and less severe side effects than typical antipsychotics.

The most significant difference between typical and atypical antipsychotics is their side effects.

Typical antipsychotics have significant extrapyramidal symptoms. These are drug-induced movement disorders. They may include:

- Dystonia: uncontrolled muscle contractions that cause repetitive movements and abnormal posture

- Akathisia: a state of restlessness

- Parkinsonism: a disorder causing tremors, slow movements, and rigidity

- Tardive dyskinesia: a chronic condition causing repetitive muscle movements in the face, neck, arms, and legs

- Tardive akathisia: a delayed start of akathisia after starting an antipsychotic drug

Extrapyramidal symptoms can be debilitating. Some people report the symptoms interfere with activities of daily living, social functioning, and speaking.

Some people report the symptoms interfere with activities of daily living, social functioning, and speaking.

Other possible side effects of antipsychotics include:

- dry mouth

- constipation

- urinary retention

- allergic reactions

Severe side effects of antipsychotics may affect heart function.

Because antipsychotics act on dopamine receptors, they may increase a person’s level of prolactin. This is a hormone released in the pituitary gland.

High prolactin levels in the blood can cause:

- abnormal breast milk production

- breast enlargement

- loss of menstrual periods

- impotence in males

- loss of orgasm in females

A note about sex and gender

Sex and gender exist on spectrums. This article will use the terms “male,” “female,” or both to refer to sex assigned at birth. Click here to learn more.

Although atypical antipsychotics have less significant side effects, they can cause:

- weight gain

- high cholesterol

- diabetes

One atypical antipsychotic called clozapine carries a risk of myocarditis, which is inflammation of the heart muscle. However, the risk of dying from myocarditis from taking clozapine is low.

However, the risk of dying from myocarditis from taking clozapine is low.

Antipsychotics have a boxed warning issued by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This is the most severe warning for a drug.

The following table lists examples of typical and atypical antipsychotics:

| Typical antipsychotics | Atypical antipsychotics |

|---|---|

| acetophenazine (Tindal) | aripiprazole (Abilify) |

| haloperidol (Haldol) | asenapine (Saphris) |

| loxapine (Adasuve) | brexpiprazole (Rexulti) |

| molindone | cariprazine (Vraylar) |

| perphenazine | clozapine (Clozaril) |

| pimozide | iloperidone (Fanapt) |

| prochlorperazine (Procomp) | lurasidone (Latuda) |

| thiothixene | olanzapine (Zyprexa) |

| trifluoperazine | paliperidone (Invega) |

| quetiapine (Seroquel) | |

| risperidone (Risperdal) | |

| ziprasidone (Geodon) |

The FDA has approved antipsychotics for various psychiatric conditions.

Different types of antipsychotics and the conditions they treat are listed below:

| Typical antipsychotics | Typical or atypical antipsychotics (except clozapine) | Clozapine |

|---|---|---|

| delusional disorders | schizophrenia | childhood schizophrenia |

| Tourette’s syndrome | schizoaffective disorder | tardive dyskinesia |

| major depressive disorder (with psychotic characteristics) | treatment-resistant mania | |

| borderline personality disorder (BPD) | obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) | |

| dementia | childhood autism | |

| substance-induced psychotic disorder | Parkinson’s disease | |

| sudden manic episode | Huntington’s disease | |

| schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (with suicidal thoughts) | ||

| severe psychotic symptoms |

Sometimes, doctors may prescribe atypical antipsychotics for conditions the FDA has not approved them for. This is called off-label prescribing.

This is called off-label prescribing.

For example, atypical antipsychotics may help people with Tourette’s syndrome, but this is an off-label use.

However, doctors can sometimes incorrectly prescribe antipsychotics. A concerning practice seen in some care homes is doctors overprescribing antipsychotic medications to older adults.

Off-label uses of antipsychotics in older adults in nursing homes include dementia-related behaviors, such as aggression and agitation. Antipsychotics are not safe when prescribed inappropriately to a vulnerable group of people.

National programs in the United States have worked to reduce the unsuitable prescribing of antipsychotics in nursing homes. While researchers note a decline in this practice, more work is needed to further reduce the improper prescribing of antipsychotics in nursing homes.

When taking antipsychotic medications, people should report any side effects to a doctor. Sometimes, changing antipsychotics can help improve the medical condition while minimizing side effects.

If a person is taking atypical antipsychotics, doctors will review their body weight and order blood tests to check for increased cholesterol and blood sugar. Follow-up appointments may also include having an electrocardiogram to evaluate heart function.

For people taking clozapine, doctors will check neutrophil levels. This is a type of white blood cell that helps the body protect itself from infections. Clozapine can drop neutrophil levels and increase a person’s risk of illnesses.

Doctors can prescribe a range of types of antipsychotics. Each type has different side effects. While some health conditions require a typical antipsychotic medication, atypical antipsychotics are often preferred.

Atypical antipsychotic medications usually have fewer and less severe side effects than typical antipsychotic medications.

Weight gain, diabetes, and high cholesterol are side effects that can occur with atypical antipsychotics. When taking antipsychotics, follow-up appointments with a doctor are crucial to a person’s care.

Antipsychotics: pharmacological group

Description

Antipsychotics include drugs intended for the treatment of psychosis and other severe mental disorders. The group of antipsychotic drugs includes a number of phenothiazine derivatives (chlorpromazine, etc.), butyrophenones (haloperidol, droperidol, etc.), diphenylbutylpiperidine derivatives (fluspirilene, etc.), etc.

Neuroleptics have a multifaceted effect on the body. Their main pharmacological features include a kind of calming effect, accompanied by a decrease in reactions to external stimuli, a weakening of psychomotor arousal and affective tension, suppression of fear, and a decrease in aggressiveness. They are able to suppress delusions, hallucinations, automatism and other psychopathological syndromes and have a therapeutic effect in patients with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. nine0005

Antipsychotics in normal doses do not have a pronounced hypnotic effect, but they can cause a drowsy state, promote the onset of sleep and increase the effect of hypnotics and other sedatives (sedatives). They potentiate the action of drugs, analgesics, local anesthetics and weaken the effects of psychostimulant drugs.

They potentiate the action of drugs, analgesics, local anesthetics and weaken the effects of psychostimulant drugs.

In some antipsychotics, the antipsychotic effect is accompanied by a sedative effect (aliphatic derivatives of phenothiazine: chlorpromazine, promazine, levomepromazine, etc.), while in others (piperazine derivatives of phenothiazine: prochlorperazine, trifluoperazine, etc.; some butyrophenones) - activating (energizing). Some neuroleptics relieve depression. nine0005

In the physiological mechanisms of the central action of neuroleptics, the inhibition of the reticular formation of the brain and the weakening of its activating effect on the cerebral cortex are essential. A variety of effects of neuroleptics are also associated with the impact on the occurrence and conduction of excitation in different parts of the central and peripheral nervous system.

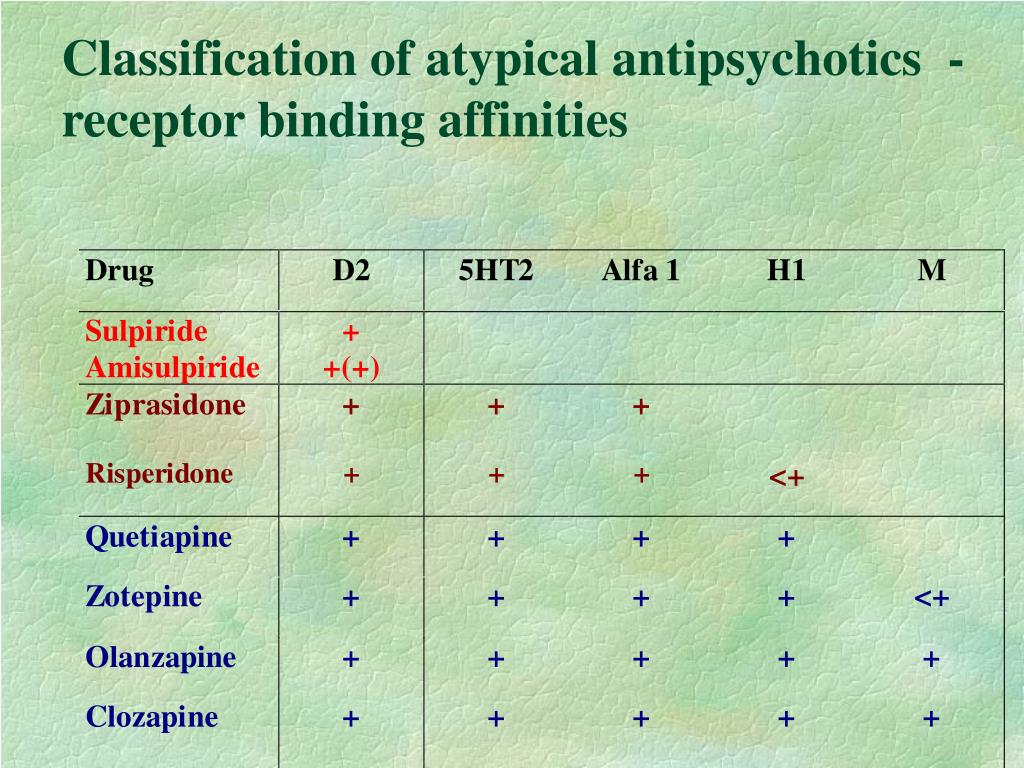

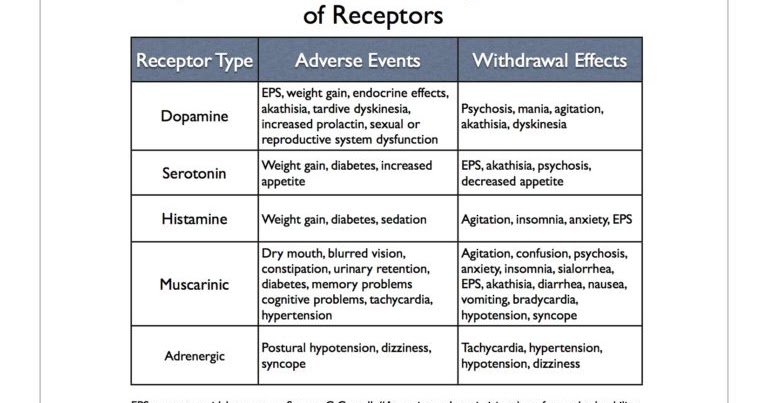

Antipsychotics change neurochemical (mediator) processes in the brain: dopaminergic, adrenergic, serotonergic, GABAergic, cholinergic, neuropeptide and others. Different groups of antipsychotics and individual drugs differ in their effect on the formation, accumulation, release and metabolism of neurotransmitters and their interaction with receptors in different brain structures, which significantly affects their therapeutic and pharmacological properties. nine0005

Different groups of antipsychotics and individual drugs differ in their effect on the formation, accumulation, release and metabolism of neurotransmitters and their interaction with receptors in different brain structures, which significantly affects their therapeutic and pharmacological properties. nine0005

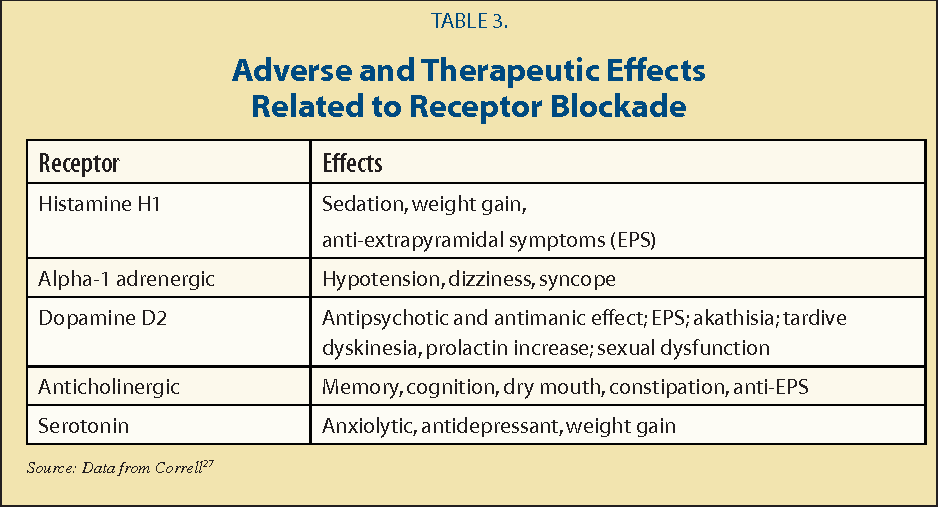

Antipsychotics of different groups (phenothiazines, butyrophenones, etc.) block dopamine (D 2 ) receptors of different brain structures. It is believed that this causes mainly antipsychotic activity, while the inhibition of central noradrenergic receptors (in particular, in the reticular formation) is only sedative. Not only the antipsychotic effect of neuroleptics, but also the neuroleptic syndrome caused by them (extrapyramidal disorders), explained by the blockade of dopaminergic structures of the subcortical formations of the brain (substance nigra and striatum, tuberous, interlimbic and mesocortical regions), where significant number of dopamine receptors. nine0005

Influence on central dopamine receptors leads to some endocrine disorders caused by antipsychotics. By blocking the dopamine receptors of the pituitary gland, they increase the secretion of prolactin and stimulate lactation, and acting on the hypothalamus, they inhibit the secretion of corticotropin and growth hormone.

By blocking the dopamine receptors of the pituitary gland, they increase the secretion of prolactin and stimulate lactation, and acting on the hypothalamus, they inhibit the secretion of corticotropin and growth hormone.

An antipsychotic with pronounced antipsychotic activity, but practically no extrapyramidal side effects, is clozapine, a piperazino-dibenzodiazepine derivative. This feature of the drug is associated with its anticholinergic properties. nine0005

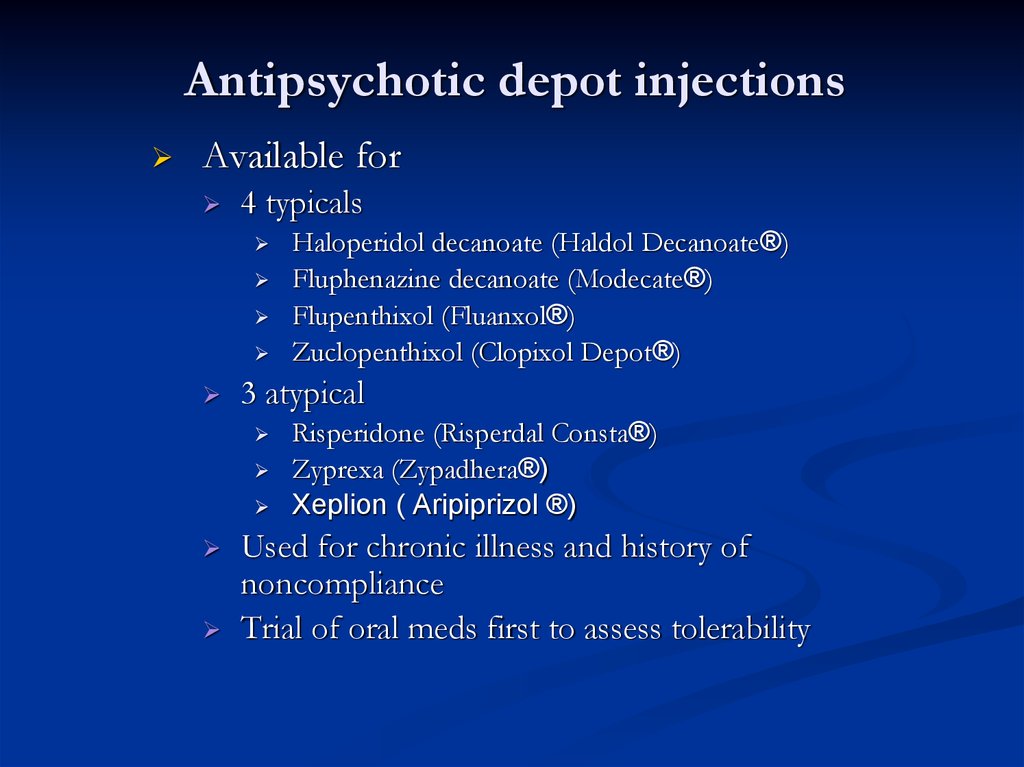

Most antipsychotics are well absorbed by different routes of administration (orally, intramuscularly), penetrate the BBB, but accumulate in the brain in much smaller amounts than in the internal organs (liver, lungs), metabolize in the liver and excreted in the urine, partly in the intestines . They have a relatively short half-life and after a single application, they act for a short time. Long-acting drugs (haloperidol decanoate, fluphenazine, etc.) have been created that have a long-term effect when administered parenterally or orally. nine0005

nine0005

Use of atypical antipsychotics in children (evidence-based practice)

In order to increase the effectiveness and safety of the use of atypical antipsychotics in pediatric practice, first of all, it is necessary to increase the requirements for the quality of diagnostics. It is necessary to make sure that the child is reasonably, in strict accordance with the diagnostic criteria for ICD-10, a psychiatric diagnosis requiring treatment with atypical antipsychotics. nine0005

Unfortunately, child psychiatrists often make incorrect diagnoses that ignore diagnostic criteria. Such a diagnosis makes it difficult to conduct therapy based on the correct use of the results of internationally controlled trials.

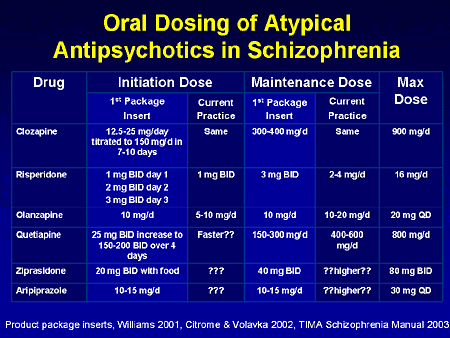

In any case, therapy should be started with the lowest doses of antipsychotics approved for pediatric practice, titrated until the patient responds to the drug or side effects occur. nine0005

Consider, as an example, a typical therapeutic situation. We are treating a 16-year-old girl with acute mania. She spent the whole night in a nightclub, was intrusive with visitors and, after being expelled from the establishment by security, tried to sneak back through the windows of the utility room. She had spent the previous nights at her computer trying to shop online. Without a driver's license, she tried to go somewhere in her parents' car.

We are treating a 16-year-old girl with acute mania. She spent the whole night in a nightclub, was intrusive with visitors and, after being expelled from the establishment by security, tried to sneak back through the windows of the utility room. She had spent the previous nights at her computer trying to shop online. Without a driver's license, she tried to go somewhere in her parents' car.

nine0039 This girl can be started with aripiprazole 2 mg daily, titrated to the target dose (10 mg daily). No less reasonable is the appointment of risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine or ziprasidone. In the process of dose titration, it is necessary to monitor changes in the condition of the adolescent. Did the girl sleep better? Has she stopped doing reckless things, wasting money? Was she able to resume school attendance? How good is her social functioning and school adjustment? For further treatment of the adolescent, doses of antipsychotics that provide a therapeutic effect but do not cause side effects should be used. nine0040

nine0040

In non-compliant adolescents who refuse to swallow tablets, we can use oral risperidone solution during the dose titration step. After stabilization of doses, it is possible to use Konsta® rispolept or Quiklet® rispolept. If risperidone is not well tolerated or higher doses of the drug (4-8 mg risperidone) are needed, I would consider paliperidone extended release slow release capsules (Invegi®). nine0040

I want to draw readers' attention to the fact that when discussing the possibility of prescribing Rispolept Konsta or Invega to children, we go beyond the FDA recommendations, but we can assume with a high degree of confidence that registration of children's indications for these dosage forms of risperidone is only a matter of time. However, you should not start treating your child with these drugs. Initially, we must consider FDA approved therapeutic alternatives. The decision to prescribe non-recommended drugs should be taken with a sense of responsibility. We must have strong arguments for such a practice. Another important procedural requirement is that the informed consent of the parents and the adolescent should be obtained before starting treatment. nine0040

We must have strong arguments for such a practice. Another important procedural requirement is that the informed consent of the parents and the adolescent should be obtained before starting treatment. nine0040

Who will treat such a patient? Most likely, it will be a psychiatrist or child psychiatrist.

Family doctors in Ukraine rarely take part in the provision of psychiatric care to children. Avoid the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders and pediatricians. Pediatric neurologists feel most confident with pediatric psychiatric patients. They prescribe neuroleptics for children more often than other internists. Unfortunately, their appointments are not always qualified. The most common indications for the appointment of neuroleptics are tic disorder, motor disinhibition, sleep disorders. Preference is given to antipsychotics of the first generation: thioridazine (sonapax), haloperidol, clozapine (leponex, azaleptin). This practice cannot be viewed positively. It needs to be stopped. nine0005

nine0005

Nevertheless, we are not talking about the introduction of a ban for internists to prescribe antipsychotics to children. Ukraine, like other European countries, faces the task of integrating mental health care for children into primary health care, expanding the range of services provided at the community level. Prescribing antipsychotics to children by general practitioners cannot be avoided.

Clinical guidelines for mental health care for general practitioners, developed by the World Health Organization's Mental Health Program, recommend that these professionals use 1 or 2 of the FDA-recommended drugs. There are four indications for prescribing antipsychotics to children: mania, hallucinatory-delusional symptoms, psychomotor agitation, Tourette's syndrome . General practitioners should have sufficient knowledge to diagnose these disorders. They should study well the side effects of the antipsychotics they prescribe, learn how to dose them correctly, titrate doses, starting with the minimum recommended in the instructions for use.

If a therapeutic response to treatment is not achieved when the target dose range is reached, the child's condition does not improve, he should be consulted with a child psychiatrist. Making further therapeutic decisions is the exclusive competence of this specialist. nine0005

The most important clinical task that the child psychiatrist has to solve at the first stage of therapy is to confirm the presence or absence of response to therapy with the prescribed antipsychotic. Such a clinical conclusion is not always obvious.

Let's return to the above clinical example. In our case with a 16-year-old girl, first of all, it is necessary to check whether she is really taking the prescribed medicine. It is not uncommon for teenagers to fake taking medication by spitting out a pill hidden under the tongue or behind the cheek after parents or medical staff stop watching them. nine0040

If a child takes the drug at the maximum recommended dose in the instructions for use within 7 days, but there is no significant change in the severity of the symptoms of the disorder, we can speak of a lack of therapeutic response and consider switching to another drug.

If maximum doses cannot be achieved due to unacceptable side effects, we should also consider changing therapy. nine0040

At any stage of therapy, either due to exacerbation of the disorder's symptoms or side effects, the adolescent's condition may become threatening to himself or others. It is advisable to hospitalize such a teenager in a psychiatric department. Further selection of antipsychotic therapy for him should be carried out in a safe environment.

In such cases, the question arises: how quickly should we cancel an atypical antipsychotic if, after its short-term use, already at the dose selection stage, we are faced with unacceptable side effects or severe complications? Is it worth it to hospitalize such a child and carry out a gradual withdrawal of the drug in a hospital, or is it more correct to simply immediately stop taking the antipsychotic? nine0005

In pediatric practice, gradual dose escalation, withdrawal, or substitution of the atypical antipsychotic is always preferred. This is not always possible, for example, in the case of acute severe complications or the unilateral decision of some patients or their parents to stop treatment. But when possible, a strategy of phasing out an antipsychotic is always preferable. It is important to be able to explain to the parents of the child that the immediate withdrawal of the drug can lead to an exacerbation of the disorder and be accompanied by no less serious side effects than continuing to take a lower dose of it. nine0005

This is not always possible, for example, in the case of acute severe complications or the unilateral decision of some patients or their parents to stop treatment. But when possible, a strategy of phasing out an antipsychotic is always preferable. It is important to be able to explain to the parents of the child that the immediate withdrawal of the drug can lead to an exacerbation of the disorder and be accompanied by no less serious side effects than continuing to take a lower dose of it. nine0005

Side effects associated with the influence of second-generation antipsychotics on the central nervous system

When prescribing atypical antipsychotics to children, drowsiness and sedation are often observed, which are among the most important side effects that should be considered [1–2]. Slow titration is aimed at their detection and prevention in children. We must not allow children in therapy to sleep in class.

During the first week of taking atypical antipsychotics, most children may experience drowsiness, which significantly affects the ability to learn. Children go to bed early, fall asleep during lessons. Reducing a single dose, distributing it over several doses, as a rule, can eliminate or mitigate side effects. Later, many children adapt to the sedation and do not show daytime sleepiness. If the dose of the antipsychotic is increased very slowly in these children, overt sedation and daytime sleepiness can be avoided. nine0005

Children go to bed early, fall asleep during lessons. Reducing a single dose, distributing it over several doses, as a rule, can eliminate or mitigate side effects. Later, many children adapt to the sedation and do not show daytime sleepiness. If the dose of the antipsychotic is increased very slowly in these children, overt sedation and daytime sleepiness can be avoided. nine0005

Can atypical antipsychotics, along with sedation and drowsiness, cause non-sedation-related cognitive impairment in children? This aspect of the clinical action of these drugs remains debatable for both child and adult psychiatric practice. Psychiatrists often describe improvement in cognitive functioning under the influence of atypical antipsychotic therapy in adolescent schizophrenia. At the same time, they often cannot answer the question: to what extent do certain antipsychotics affect the qualitative and quantitative characteristics of thinking and memory in children. This issue is relevant when prescribing antipsychotics to children of preschool and primary school age. The FDA has included information about cognitive impairment caused by atypical antipsychotics in its safety databases. nine0005

The FDA has included information about cognitive impairment caused by atypical antipsychotics in its safety databases. nine0005

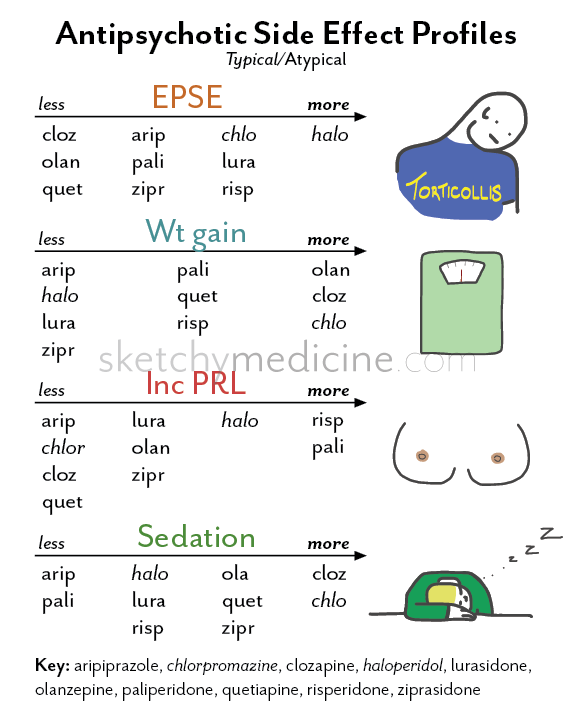

Extrapyramidal side effects has traditionally been regarded as a central concern for the safety of classical neuroleptic therapy in adults. It is customary to distinguish between muscle rigidity, tremor, akinesia (manifestations of parkinsonism) and restlessness (akathisia). Extrapyramidal side effects occur, although much less frequently, in the treatment of second-generation antipsychotics.

Children and adolescents are the most susceptible and sensitive to such side effects [2]. They are observed at the use of lower doses compared to adults. Over time, children and adolescents often adapt to taking antipsychotics, which is manifested in the mitigation of extrapyramidal symptoms, increasing doses of antipsychotics, when taking which side effects are not observed. A slow dose increase, a decrease in the peak concentrations of the antipsychotic in the child's blood serum helps to prevent the occurrence of dangerous extrapyramidal side effects. nine0005

nine0005

How can peak serum concentrations of antipsychotics be reduced? There are two ways: 1) increasing the frequency of administration, while the daily dose of the neuroleptic should be divided into 2–3–4 doses; 2) the use of dosage forms with a slow release of the active substance, for example, slow-release tablets of the active metabolite of risperidone paliperidone (Invega® Extended-Release Tablets) instead of rispolept tablets or rispolept solution for drinking.

At the beginning of antipsychotic therapy, one is more likely to encounter dystonia . It can develop even after a single dose of the first dose of an antipsychotic or during the first days of treatment, it is very painful for the child and can cause his subsequent non-compliance. The risk of developing dystonia is related to the dose used. It can be reduced by slowly and carefully titrating the drug.

The phenomena of drug-induced parkinsonism often develop during the first 7-10 days of antipsychotic therapy.

Akinesia - "feeling of motor stiffness" - is often mistakenly considered as a natural consequence of the psycholeptic action of an atypical antipsychotic. If the dose of neuroleptic is not reduced in a timely manner, akinesia is replaced by akathisia.

Akathisia is a clinical syndrome characterized by a persistent or recurrent unpleasant feeling of internal motor restlessness, an internal need to move or change position, and manifests itself in the inability of the patient to sit still in one position for a long time or to remain motionless for a long time. Often, akathisia that occurs in the first week of treatment is regarded by a specialist as an increase in anxiety or an exacerbation of manic symptoms. The doctor explains the symptoms that have appeared by the fact that the neuroleptic has not yet had time to act, and the psycholeptic effect of atypical antipsychotics is slightly expressed, and often makes an erroneous decision to increase the dose of the drug more quickly. nine0005

nine0005

When treating children with atypical antipsychotics, we are often faced with the difficult task of qualifying the primary response to the drug: we must distinguish between overdose-related akathisia and increased anxiety and emotional instability with exacerbation of the underlying condition at therapeutically ineffective doses. Akathisia in the appointment of neuroleptics in children with impaired activity and attention can lead to increased hyperactivity and impulsivity and the appearance of severe emotional instability. nine0005

When conducting a differential diagnosis, it can be important to find out from a child whether he experiences mental discomfort from the need to move a lot or when trying to restrain his restlessness. With anxiety or manic symptoms, children never make such complaints.

Dyskinesia in the form of persistent violent movements of the facial muscles, shoulders, legs, fingers, tongue in patients receiving treatment with neuroleptics is usually associated with the consequences of long-term neuroleptic therapy with classical antipsychotics. It has been shown that dyskinesias significantly reduce the quality of life of patients, stigmatize patients, impede social communications, and create difficulties in finding employment. nine0005

It has been shown that dyskinesias significantly reduce the quality of life of patients, stigmatize patients, impede social communications, and create difficulties in finding employment. nine0005

Poor quality of life and stigmatization of patients with schizophrenia are often associated with tardive dyskinesia . There is a point of view that the stigma of public perception of patients with schizophrenia is more associated with this extrapyramidal side effect than with the productive and negative symptoms of the disorder.

Traditional risk factors for the development of tardive dyskinesia are older age, female sex, white race. Adults receiving atypical antipsychotics for more than 1 year have a 6-fold lower risk of developing tardive dyskinesia compared with conventional antipsychotic therapy for a similar period of time. nine0005

Children and adolescents appear to be at a lower risk of developing this complication than adults. In the analysis of case histories of 783 children and adolescents treated with risperidone for more than a year, tardive dyskinesia was registered in 0. 4% of cases [3].

4% of cases [3].

We need to monitor the frequency of this complication. It may increase over time as there is a trend in child psychiatric practice to use higher doses of atypical antipsychotics and to increase the average duration of treatment. nine0005

Tardive dyskinesia in children may be a consequence of the withdrawal of antipsychotics. They occur even after slow discontinuation of atypical antipsychotic therapy.

This clinical phenomenon is easy to explain. Children who stop taking antipsychotics, especially if treatment is stopped abruptly, may have increased levels of dopamine neurotransmission. Blockade of dopamine receptors can cause activation of unblocked parts of the brain's dopaminergic system. Usually these violations, often quite severe, are temporary. We need to explain to parents that motor dyskinesias are likely to decrease over time. In cases where motor tics and vocalizations are excessive, they can be stopped by resuming the use of an antipsychotic at a dose that provides a complete reduction in symptoms, followed by a very slow dose reduction. The FDA recommends a dose reduction of 25% per month. nine0005

The FDA recommends a dose reduction of 25% per month. nine0005

It is not always easy to distinguish between neuroleptic withdrawal dyskinesias and the initial manifestations of tardive dyskinesia.

The determining factor is the clarification of the time of their appearance. It is important to find out whether they took place before the start of taking antipsychotics, whether their severity changed with varying doses, if this occurred during treatment. It is also important to confirm the compliance of the child. When dyskinesias appear or worsen, it is important to make sure that he continues to take the medicine. Sometimes, when giving a child a drug, the parents let the child go without making sure that the drug has been swallowed. The child can hide the tablet under the tongue or behind the cheek and then spit it out. In such a case, orally dispersible tablets or drinking solutions can be very helpful. Thus, a clear correspondence between the actual use of drugs and the prescription should first be established, and then the classification of movement disorders should be carried out. nine0005

nine0005

In pediatric practice, it is very important to distinguish between dyskinesias caused by antipsychotic therapy and dyskinesias due to concomitant neurological and psychiatric disorders. The child before the start of treatment must be carefully examined. It is necessary to distinguish between motor disorders associated with hypoxic-ischemic brain damage and birth trauma, dyskinesia in general developmental disorders (disorders from the autism spectrum), gross and fine motor disorders in children with hyperkinetic disorder. nine0005

The presence of dyskinesias associated with a neurological disorder is a predictor of poorer tolerance of atypical antipsychotics in children. The severity of motor impairment during the abolition of antipsychotics in these children may be greater than before they were taken. Rapid discontinuation of therapy can lead to an increase in motor disorders, the appearance of motor and vocal tics, and pathological habitual actions. In some cases, heavy violent movements and vocalizations make it impossible to attend school. nine0005

nine0005

Atypical antipsychotics for tic disorders and de la Tourette's syndrome in children

In transient tics, antipsychotics should be avoided in children. The disease proceeds in waves, and periods of exacerbation of tic symptoms are replaced by regular periods of mitigation of motor disorders and remissions. The duration of the disorder usually does not exceed 12 months. This disorder does not require treatment. If tics are multiple, worse with age, accompanied by echopraxia, which in some patients may be obscene, antipsychotic therapy is indicated. nine0005

Children with chronic motor and vocal tics are characterized by increased levels of dopamine neurotransmission in the motor tracts. This determines the affinity of motor disorders in de la Tourette's syndrome to antipsychotics that act on dopamine receptors of the striopallidar system. When deciding on the pharmacotherapy of Tourette's syndrome, one should always weigh what will affect the child's quality of life to a greater extent - tics or side effects associated with long-term use of antipsychotics or clonidine. nine0005

nine0005

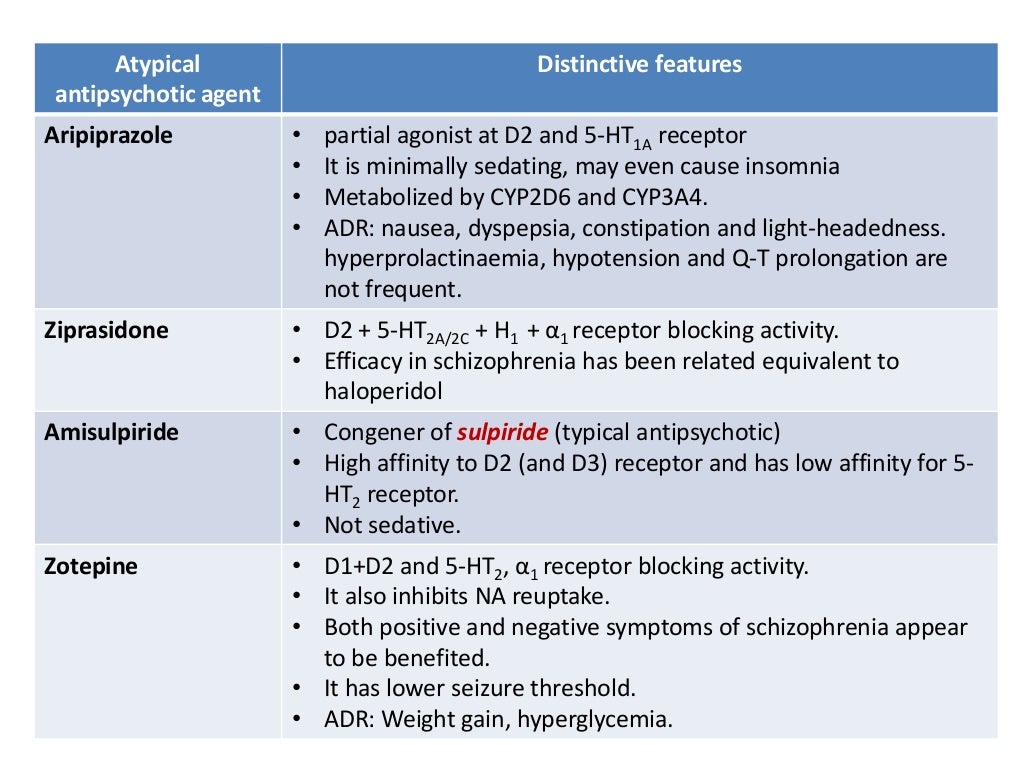

In 2011, clinical guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of Tourette's syndrome were published in the European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry [4]. Risperidone, aripiprazole, pimozide, sulpiride, tiapride and haloperidol received a positive assessment from the experts.

Due to extrapyramidal side effects and the risk of developing tardive dyskinesias, long-term use of haloperidol and pimozide in pediatric practice is not possible. Tiapride, sulpiride have the largest evidence base, are better tolerated and are the first-line drugs of choice for this disorder. In a number of countries, tiapride is included in clinical protocols for the treatment of Tourette's syndrome. Our data also indicate good efficacy and tolerability of amisulpride. nine0005

Quetiapine, olanzapine, and ziprasidone are not drugs of choice in the treatment of chronic tic disorder.

In Tourette's syndrome, the neuroleptic should be prescribed at doses that stop motor disturbances in children, but do not cause unacceptable side effects. After achieving a clinical effect and therapy for 4-6 months, the antipsychotic is very slowly, over 6-12 months, canceled.

After achieving a clinical effect and therapy for 4-6 months, the antipsychotic is very slowly, over 6-12 months, canceled.

Metabolic and endocrine side effects of the use of atypical antipsychotics in pediatric practice

When using traditional antipsychotics, psychiatrists are more concerned about monitoring extrapyramidal side effects and the risk of developing tardive dyskinesia. They usually have a sufficient level of competence to diagnose neurological side effects early.

Atypical antipsychotics are more associated with cardiometabolic side effects - weight gain, impaired glucose metabolism and lipid metabolism. Psychiatrists, child psychiatrists do not always have sufficient training for the early detection and evaluation of such disorders. nine0005

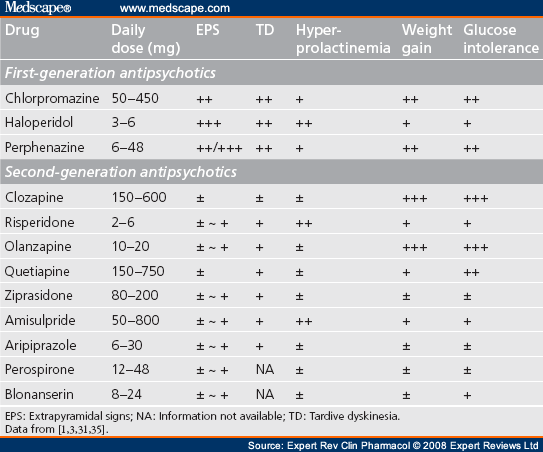

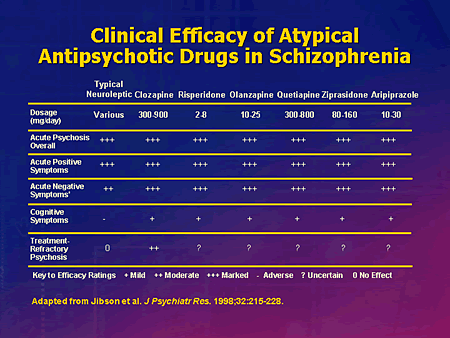

All antipsychotic drugs can cause metabolic side effects, but their likelihood and severity vary greatly. Clozapine and olanzapine cause metabolic disturbances most frequently. Risperidone and quetiapine have a significant but lower risk than olanzapine and clozapine. To the least extent, ziprasidone and aripiprazole can cause metabolic disorders.

To the least extent, ziprasidone and aripiprazole can cause metabolic disorders.

There is some evidence that children are more sensitive to metabolic side effects than adults. One study found that in adults, aripiprazole therapy causes fewer metabolic disorders than in children [5]. Children are more sensitive to therapy with any antipsychotic, such therapy has a greater risk of metabolic disorders, and therefore monitoring of the safety and tolerability of therapy in them should be carried out more strictly. nine0005

Before prescribing an atypical antipsychotic to a child, a family history of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease should be ascertained. It is necessary to determine the basic level of fasting glucose, lipid profile, evaluating total cholesterol, triglycerides, lipoproteins (low and high density), measure weight, height and blood pressure. It is recommended to monitor the indicators of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, the weight of the child during treatment every 6 months [2, 6]. nine0005

nine0005

Many psychiatrists fail to diagnose hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia in children taking atypical antipsychotics. They do not always pay attention to the increase in the level of cholesterol and low-density lipoproteins, in particular triglycerides, which are closely associated with insulin resistance.

Therapy with atypical antipsychotics is often accompanied by significant weight gain, requiring special measures to reduce it. The developed phenomena of insulin resistance are associated with type 2 diabetes and require special treatment. nine0005

Physicians who monitor the side effects of atypical antipsychotics in children may overestimate some of the child's complaints, mistakenly regarding them as manifestations of cardiometabolic disorders.

For example, children taking atypical antipsychotics often complain of dry mouth. This symptom can be unreasonably interpreted as a manifestation of diabetes mellitus. With a detailed questioning of most children, it turns out that they complain more about stickiness in the mouth, the viscosity of saliva than the feeling of thirst. An ice cube or chewing gum can eliminate the discomfort that indicates an autonomic imbalance in the early stages of taking antipsychotics, and not the overt symptoms of diabetes. nine0005

An ice cube or chewing gum can eliminate the discomfort that indicates an autonomic imbalance in the early stages of taking antipsychotics, and not the overt symptoms of diabetes. nine0005

Another example of a false-positive diagnosis of cardiometabolic disorders: not every increase in height and weight in children taking atypical antipsychotics is in favor of the metabolic syndrome. It is important to establish not an increase in absolute values, but an excess of age standards. Some general practitioners pay attention not so much to weight as to the waist size of children. An increase in waist circumference is a natural sign of metabolic syndrome, but the American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend using this indicator as a screening indicator (primarily because it can be very difficult to make reliable measurements in real practice). More reliable is the estimated BMI (body mass index). nine0005

Metabolic syndrome is diagnosed when at least three out of five diagnostic criteria are met in children [7]: 1) the presence of sex- and age-adjusted overweight (obesity) ≥ 95 percentiles; 2) having sex- and height-adjusted high blood pressure (hypertension) ≥ 90 percentiles; 3) triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL (1. 7 mmol/L) or more; 4) NSAID cholesterol < 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) for both sexes; 5) Elevated baseline glucose (hyperglycemia) ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or higher. nine0005

7 mmol/L) or more; 4) NSAID cholesterol < 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) for both sexes; 5) Elevated baseline glucose (hyperglycemia) ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or higher. nine0005

The presence of C-reactive protein is also not among the indicators to be screened when prescribing atypical antipsychotics to children. The appearance of C-reactive protein is closely related not only to the toxic effect of atypical antipsychotics, but also to cardiovascular diseases caused by viral and bacterial infections. This makes it difficult to interpret abnormal readings.

In real clinical practice, it is much easier to follow common indicators of the metabolic syndrome. But it is also important not to ignore dysmetabolic changes that do not reach the criteria of the metabolic syndrome. nine0005

Atypical antipsychotic weight gain

There is a point of view that children with an asthenic constitution are less likely to develop the metabolic syndrome when taking atypical antipsychotics than those with a pycnotic one. These ideas have not found scientific confirmation. It is considered proven that the baseline BMI [7] is not a predictor of greater or lesser weight gain during therapy. It has also been established that there are individuals prone to the manifestation of this side effect and not prone to dysmetabolic disorders when taking any atypical antipsychotics. The best way to predict the risk of weight gain when treated with atypical antipsychotics is to monitor weight during the first four weeks of taking the drug. Height-adjusted weight gain during these four weeks shows a high degree of correlation with weight gain during subsequent therapy. nine0005

These ideas have not found scientific confirmation. It is considered proven that the baseline BMI [7] is not a predictor of greater or lesser weight gain during therapy. It has also been established that there are individuals prone to the manifestation of this side effect and not prone to dysmetabolic disorders when taking any atypical antipsychotics. The best way to predict the risk of weight gain when treated with atypical antipsychotics is to monitor weight during the first four weeks of taking the drug. Height-adjusted weight gain during these four weeks shows a high degree of correlation with weight gain during subsequent therapy. nine0005

Olanzapine causes the greatest weight gain in children, risperidone and quetiapine lead to more moderate weight gain. To the least extent, an increase in BMI is accompanied by therapy with ziprasidone and aripiprazole.

The risk of a significant increase in BMI in children is much higher than in adults. Significant weight gain occurs in 2–6% of adults and in 25–40% of children under 8 years of age. According to our data, a significant increase in weight when prescribing risperidone to children of preschool and primary school age was observed in 42%, in the treatment of olanzapine - in 83% of cases. We have not registered any case of a significant increase in the weight of the child after the appointment of quetiapine and aripiprazole. nine0005

According to our data, a significant increase in weight when prescribing risperidone to children of preschool and primary school age was observed in 42%, in the treatment of olanzapine - in 83% of cases. We have not registered any case of a significant increase in the weight of the child after the appointment of quetiapine and aripiprazole. nine0005

Atypical antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia

The problem of side effects associated with high prolactin levels in antipsychotic therapy was actualized by clinicians several decades ago. When using atypical antipsychotics in adult patients, the risk of such side effects is lower than when treated with conventional antipsychotics. Children and adolescents appear to be at a higher risk of developing side effects associated with high prolactin levels than adults [8]. nine0005

When prescribing atypical antipsychotics to children, we are mainly concerned with the possibility of prolactin reaching levels leading to hypogonadism. High prolactin can lead to suppression of the production of sex hormones and impaired puberty. Along with hypogonadism, long-term high prolactin levels are associated with osteoporosis.

High prolactin can lead to suppression of the production of sex hormones and impaired puberty. Along with hypogonadism, long-term high prolactin levels are associated with osteoporosis.

High prolactin levels are most commonly seen with risperidone, and the risk of prolactinemia is lower with other antipsychotics. nine0005

It is difficult to say what level of prolactin is unacceptable in terms of the risk of developing hypogonadism and can serve as a basis for reconsidering further therapy.

In prepubertal age, the level of prolactin does not significantly affect the sexual development of a child, and during puberty, even relatively low levels of prolactin can significantly affect the sexual development of a teenager.

Unfortunately, we do not have reliable data on the relationship between the level of prolactin and delayed sexual development in children and adolescents, which does not allow us to predict the risk of these complications by the level of prolactin during antipsychotic therapy. We also do not know subclinical levels of prolactin, which may be potentially harmful to prepubertal child development and puberty. Additional specific studies are needed. However, if we register a prolactin level of 200 ng/dL or higher in a child, then this should be a source of concern. In the presence of high prolactin, not associated with the use of atypical antipsychotics, we must first rule out a pituitary tumor in the child. nine0005

We also do not know subclinical levels of prolactin, which may be potentially harmful to prepubertal child development and puberty. Additional specific studies are needed. However, if we register a prolactin level of 200 ng/dL or higher in a child, then this should be a source of concern. In the presence of high prolactin, not associated with the use of atypical antipsychotics, we must first rule out a pituitary tumor in the child. nine0005

Current recommendations are to look for clinical signs and symptoms of potential hypogonadism in children receiving antipsychotics and, if screening is positive, to monitor prolactin levels.

In the presence of endocrine disorders associated with hyperprolactinemia, it is advisable to consider changing the atypical antipsychotic or reducing its dose.

The presence of amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea in girls with an irregular menstrual cycle is of relative diagnostic value and does not necessarily indicate an imbalance of sex hormones. Galactorrhea is more likely to indicate a high level of prolactin and a violation of estrogen levels. In the case of galactorrhea, even without determining the level of prolactin in the blood serum, it is advisable to reduce the dose of the atypical antipsychotic. Another sign of hypogonadism is gynecomastia, an enlargement of breast tissue. Both galactorrhea and gynecomastia can be diagnosed in both boys and girls. Weight gain in boys can occur in large part through an increase in breast tissue. In these cases, palpation can establish a glandular consistency of the mammary glands. nine0005

Galactorrhea is more likely to indicate a high level of prolactin and a violation of estrogen levels. In the case of galactorrhea, even without determining the level of prolactin in the blood serum, it is advisable to reduce the dose of the atypical antipsychotic. Another sign of hypogonadism is gynecomastia, an enlargement of breast tissue. Both galactorrhea and gynecomastia can be diagnosed in both boys and girls. Weight gain in boys can occur in large part through an increase in breast tissue. In these cases, palpation can establish a glandular consistency of the mammary glands. nine0005

It is logical to assume that high prolactin levels and changes in testosterone and estrogen levels are accompanied by changes in sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions, but screening for such disorders in pediatric practice has no clinical significance. Many teenagers do not know what normal sexual behavior should look like at their age and are unable to objectively assess their sexuality.

The efficacy and safety of the use of atypical antipsychotics in children largely depend on their adherence to a healthy lifestyle and adherence to regimen measures

The effectiveness of antipsychotic therapy in children is largely associated with compliance with a number of regimen measures and the formation of a commitment to a healthy lifestyle. The use of atypical antipsychotics can lead to increased appetite and increased food intake by the child. It is necessary to control the amount of food eaten and its calorie content. With dietary recommendations and sufficient physical activity, it is possible to significantly reduce the risk of metabolic disorders. nine0005

The use of atypical antipsychotics can lead to increased appetite and increased food intake by the child. It is necessary to control the amount of food eaten and its calorie content. With dietary recommendations and sufficient physical activity, it is possible to significantly reduce the risk of metabolic disorders. nine0005

In some patients, the need for smoking increases. Smoking, on the one hand, improves the tolerance of extrapyramidal side effects, on the other hand, it can reduce the antipsychotic activity of clozapine and olanzapine.

The effectiveness of ziprasidone is largely dependent on the caloric content of the diet. Absorption of the drug depends on food intake. If the calorie content of the latter is less than 500 calories, the serum concentration of the drug may be 50% lower. nine0005

A big problem is the interaction of atypical antipsychotics with alcohol. Obviously, adolescents suffering from a mental disorder should be prescribed abstinence from alcohol and drugs. Another question is how to ensure the implementation of these prescriptions. It is difficult to be sure that adolescents who are integrated into a peer group will be able to observe the regime of absolute abstinence from drinking alcohol. Teenagers can stop taking medication if we tell them to never mix medication with alcohol. We need to talk to the teenager about a realistic treatment strategy, including for episodic withdrawal violations. For example, we may recommend that a teenager, in an exclusive case, limit himself to taking only one drink and postpone the medication to a later time, for example, to drink it after returning home from a party. nine0005

Another question is how to ensure the implementation of these prescriptions. It is difficult to be sure that adolescents who are integrated into a peer group will be able to observe the regime of absolute abstinence from drinking alcohol. Teenagers can stop taking medication if we tell them to never mix medication with alcohol. We need to talk to the teenager about a realistic treatment strategy, including for episodic withdrawal violations. For example, we may recommend that a teenager, in an exclusive case, limit himself to taking only one drink and postpone the medication to a later time, for example, to drink it after returning home from a party. nine0005

Adherence to therapy is a prerequisite for its effectiveness. When prescribing atypical antipsychotics to children, we are always looking for a balance between the severity of the deterioration in social functioning in the case of an untreated mental disorder and the somatic consequences, a reduction in their life expectancy due to cardiometabolic side effects.